Types and sources of salts causing exfoliation and efflorescence in stone relics at Yongling Mausoleum

Introduction

The degradation of cultural relics is often driven by complex interactions of physical and chemical processes1. Among them, salt weathering is widely recognised as a key factor in the degradation of historic buildings, archeological sites, and archeological relics2. At the macro level, salt crystallization manifests as visible decay in stone materials, including blistering, efflorescence, exfoliation, and detachment, leading to progressive material loss from the surface into deeper layers3,4. Understanding and mitigating salt-induced deterioration is crucial for the effective preservation of cultural heritage.

Currently, research on salt deterioration in heritage relics primarily focuses on three key areas: the identification of the salts and their sources, the mechanisms underlying salt weathering, and methods for desalination and cleaning. Since the mid-20th century, scholars have explored the mechanisms of salt-induced degradation, which are often categorized into five main hypotheses: crystallization pressure, hydration pressure, thermal expansion, osmotic pressure, and chemical weathering5. The predominant mechanism involves the destructive stresses exerted during salt crystallization and hydration. Salt dissolved in water enters the cultural relics by capillarity and infiltration as liquid6. Scholars have extensively documented the description that temperature and humidity variations can cause cultural relics7,8,9,10,11. Even minor fluctuations in these thermo-hygrometric parameters can lead to salt crystallization at various depths within the stone or on its surface. The position of crystallization typically follows a sequence from slightly soluble to highly soluble salts up to an invariant region12.

The crystallization pressure mechanism, in particular, has been widely discussed5,6,13,14. Salts with identical anions and cations can form multiple phases under varying temperature and humidity conditions15, with examples including Na2SO4, CaSO4, MgSO4, Na2CO3, and MgCl2. These phase transitions are often accompanied by changes in volume and hydration pressure. When water molecules absorbed by minerals enter the crystal lattice of salts, the salts undergo repeated cycles of hydration and dehydration as the amount of water incorporated into the structure increases or decreases. During these phase transitions, the crystal framework expands and contracts, leading to volumetric changes in the mineral. The resulting internal pressure accelerates the alteration of the rock’s mineral composition. For a given salt, the hydration pressure is inversely related to temperature: higher temperatures reduce the pressure generated by hydration, while increased humidity amplifies this pressure16. For example, when thenardite solution transforms into mirabilite crystals, its volume increases by approximately 314%17. Similarly, when MgSO₄ undergoes hydration to form epsomite, its volume can increase by roughly 2.5 times18.

Research on salt weathering largely hinges on identifying the types and sources of salts. Rodriguez-Navarro5 used SEM to observe the crystallization of Na₂SO₄. Moussa19 analyzed the salts in the mortars of Wadi El Natrun using XRD and ICP-AES, addressing the challenges posed by limited sample availability. Siedel20 employed XRD to identify gypsum, magnesium sulfates, and sodium as the primary salts affecting buildings and monuments in Saxony. Sulfates were associated with air pollution from the 19th century to the late 20th century. Similarly, XRD and EDAX analysis of the Yungang Grottoes sandstones revealed sulfate deposits formed by chemical reactions between carbonate and atmospheric gases like O₂, SO₂, and CO₂ in moisture21. IC and XRD were applied to study the stone and salts of Oya-ishi, and correlations between salt composition, microclimate, rainwater, and groundwater were used to investigate the degradation mechanisms22. The study of rock salt weathering at the Nan Kan Grottoes examines the types of crystalline salts present, their sources, and the associated ion transport processes23. Additionally, it evaluates how the mineral composition and porosity of the rock influence its resistance to both salt and acid weathering24.

Two primary protective strategies are employed to mitigate salt weathering. One involves environmental control, aiming to reduce salt crystallization or promote the formation of less harmful salt phases25. The other focuses on the removal of salts from deteriorating zones. Desalination measures for porous silicate cultural relics generally began with the mechanical removal26 of surface crystalline salts. This was followed by the application of deionized water injection, poultices27, and crystallization inhibitors28 to mitigate and remove salts from within the material.

Significant progress has been made in understanding the degradation mechanisms and developing protection and restoration strategies for stone cultural relics preserved in open-air environments29. However, more research is needed on stone relics in closed or semi-open humid environments, where deterioration is primarily due to water infiltration, salt transport, and salt crystallization. This gap in research is crucial, as the unique environmental conditions of such settings pose distinct challenges to the preservation of these vulnerable cultural artifacts.

In this study, the serious salt weathering of sandstone artifacts from the royal tomb in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China, was studied. The study has two primary objectives. The first is to identify the types and sources of salts affecting the relics. The second is to examine the mechanisms of salt-induced deterioration and assess the associated risks. The findings aim to provide a foundation for developing effective strategies to mitigate and prevent salt-related deterioration of these valuable stone artifacts (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Methods

Description of the mausoleum

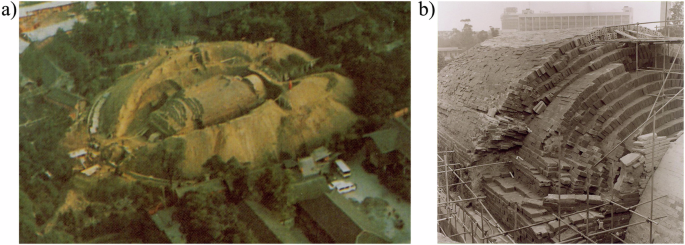

The Yongling Mausoleum, the tomb of Wang Chien, the founding emperor of the Former Shu Dynasty, is located at No. 10 Yongling Road in Jinniu District, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China. This site holds historical significance as the first imperial mausoleum in China to be excavated under the guidance of modern archeological methods in 194230. In 1961, following the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the mausoleum was designated as a national key cultural relic. The tomb was constructed at ground level. The chamber, made of red sandstone, measured 23 m in length and approximately 6 m in both width and height. Vertical and overhead walls, with a thickness of 6 m, were constructed using blue bricks, forming the structural framework around the sandstone. Above this brick structure, a circular grave mound measuring 80 m in diameter and 15 m in height was constructed using yellow rammed earth (Fig. 1)31. Within the tomb, numerous valuable artifacts are preserved, including a seated statue of Wang Chien, an imperial bed, a sandstone basin, 12 stone carvings, and the coffin platform32.

a The aerial photograph, (b) the blue bricks of the outer layer of the chamber.

Among these artifacts, the coffin platform stands out, adorned with carvings of 24 Gigaku figures holding 23 different instruments across three sides33. These carvings showcase an extraordinary level of craftsmanship, with a lifelike style that reflects a sophisticated understanding of musical instruments. The ensemble is the most complete of its kind from the period and serves as a critical resource for studying the musical practices and orchestra organization of the Tang Dynasty34. Research on the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, known for its frequent regime changes and complex cultural landscape, is relatively scarce compared to other historical eras. The Yongling Mausoleum, which adhered to the Tang Dynasty funeral rites, is a vital remnant of this period, providing essential materials for understanding the politics, economy, culture, and religion of the era.

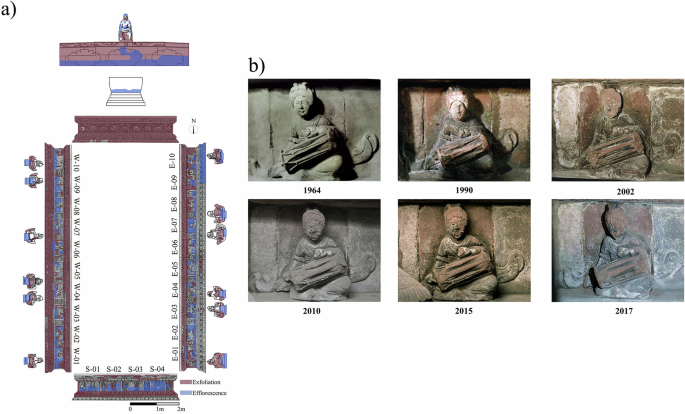

Although the mausoleum underwent repairs in 1989 to address the water seepage problem and stabilize the surrounding environment, salt infiltration remains a persistent issue due to the high humidity in the local microclimate and the incomplete removal of salts. Based on the tomb’s structural layout and the distribution of stone artifacts, 9 temperature and humidity sensors were strategically placed across the tomb and outside the door. Detailed information regarding the sensor locations and their specifications can be found in the microenvironment monitoring section of the supplementary materials. The temperature ranges from 15 to 22.6 °C, and relative humidity fluctuates between 60% and 100%. According to the model distributions, the antechamber had a high temperature and low relative humidity compared with the main hall and the postchamber. The changes were the greatest on the south side. On the east side of the front part, the relative humidity was low near the coffin bed and high near the wall35. A comparative analysis of photographs taken between 1964 and 2017 demonstrates that deterioration, including exfoliation and efflorescence (Fig. 2a), is ongoing, leading to further degradation of facial and hand details (Fig. 2b).

a Degradation distribution in the main hall and postchamber, (b) photography monitoring of E-01. The red areas represented exfoliation, and the blue areas represented efflorescence.

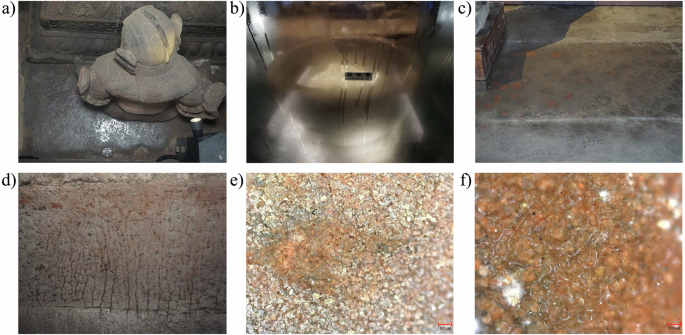

This research investigates the processes of detachment, discoloration, and deposition, with a particular focus on exfoliation and efflorescence. The exfoliation observed in the stone cultural relics within the royal tomb is characterized by the formation of reddish, curled layers, measuring approximately 2–12 mm in thickness, detached from the stone surface.

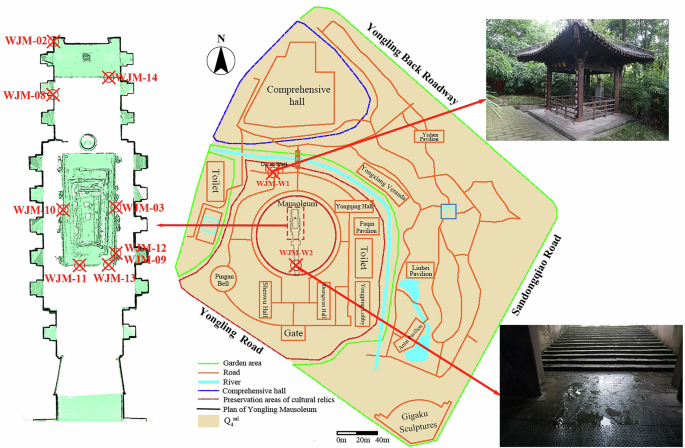

Materials

Sampling was conducted based on the mausoleum’s architectural structure, the distribution of artifacts, and the types and patterns of weathering phenomena. A total of 10 solid samples were collected from various locations within the royal tomb, along with 2 liquid samples from the surrounding environment. The sampling positions are illustrated in Fig. 3. Descriptions of the representative samples, along with the corresponding analyses performed, are detailed in Table 1.

Schematic diagram of the sampling locations of the Yongling Mausoleum.

Methods

The collected samples (Table 1) underwent a range of petrographic, physical, and chemical analyses to characterize their composition and identify the salts causing degradation. The methods and instruments employed for this research are outlined in Table 2.

Basic physical properties measurement

Basic physical properties were determined in accordance with the Standard for Testing Methods of Engineering Rock Mass (GB/T 50266-2013). The measured parameters include dry density, grain density, water saturation coefficient, permeability coefficient, moisture content, wave velocity, hardness, compressive deformability, and tensile strength.

Mercury intrusion porosimetry measurement

Mercury intrusion testing was performed following Pore Size Distribution and Porosity of Solid Materials by Mercury Porosimetry and Gas Adsorption, Part 1: Mercury Porosimetry (GB/T 21650.1-2008), using an AutoPore V 9620 automatic mercury porosimeter. The instrument measured pore volume, porosity, and pore size distribution of the rock samples. Its operating pressure ranges from 1.5 to 350 kPa for low-pressure measurements and from 140 kPa to 420 MPa for high-pressure measurements.

X‑ray diffraction (XRD)

The mineralogical and crystalline salt compositions of the samples were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis using an Empyrean diffractometer (Cu Kα radiation, 60 kV, 40 mA, angle range 11°–168°, scanning speed 15°/s, step size 0.0001°). XRD data were analyzed using Jade software. The samples were ground into a fine powder using a pestle and mortar.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The chemical bonds of the samples were analyzed using a Nicolet iN10 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Thermo Scientific Corporation) in a diamond cell. The acquisition mode was set to attenuate total reflection, with a spectral range of 4000–450 cm–1, a spectral resolution of 4 cm–1, and 64 scans. Each sample was analyzed at 25 °C, and data were collected using the OMNIC acquisition system. Prior to analysis, the samples were ground into a fine powder using a pestle and mortar.

Micro‑Raman spectroscopy (μ‑RS)

The salt composition of different positions was qualitatively analyzed using a HORIBA XploRA PLUS Raman spectrometer coupled with an Olympus microscope and an integrated motorized stage. Raman spectra were acquired under 50× and 100× objective lenses, using either a 532 nm or 785 nm laser. The laser output power ranged from 15 to 30 mW (532 nm) and 10 to 50 mW (785 nm). Spectra were recorded over a range of 50–2000 cm–1, with a collection time of 15–25 s and 2 accumulations. The instrument was calibrated using the 520 cm-1 silicon Raman band.

Ion chromatograph (IC)

Ion chromatography was performed using the HIC-10A super IC system (Shimadzu, Japan). The specific models and parameters of the components are provided in Table 3. System control, data acquisition, and processing were carried out using the LCsolution Ver. 1.21 sp1 chromatography workstation. The experimental conditions for ion chromatography are detailed in Tables 4, 5.

Polarized light microscope (PLM)

A Leica DM2700P polarized light microscope was used to examine thin sections of rocks (22 mm × 22 mm, 0.3 mm thick). The samples were observed under both single and orthogonal polarization conditions to determine their rock type and characteristics, respectively.

Optical microscopy (OM)

The surface morphology of the samples was examined using a KEYENCE VHX-6000 ultra-depth-of-field 3D video microscope. The microscope provided a magnification range of 20× to 2000×.

Salt extraction from stone powder

The stone powder was examined under a high-magnification microscope, and any crystalline salts identified were extracted. A mixture of stone powder and deionized water was prepared in a mass ratio of 1:10. After thorough stirring, the mixture was subjected to ultrasonic vibration for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 3000 r/min for 10 min. One milliliter of supernatant was diluted to 50 milliliters and left to settle for 24 h for subsequent IC analysis. The remaining supernatant was dried to isolate salt crystals, which were then analyzed using OM, SEM-EDS, FTIR, and μ‑RS.

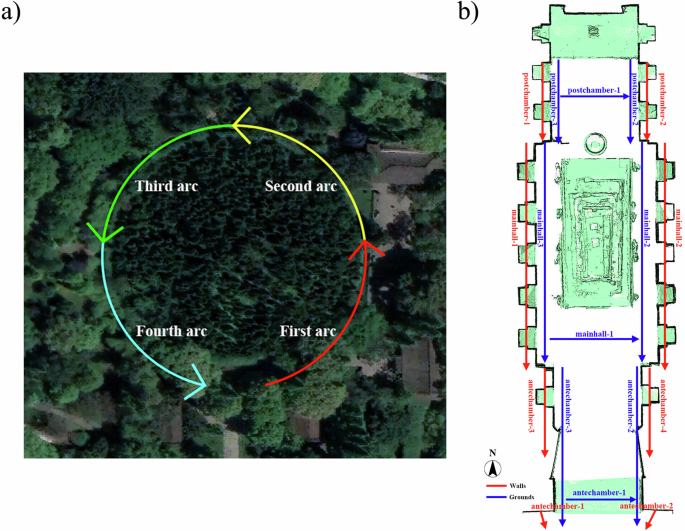

Detection of structural defects in the tomb

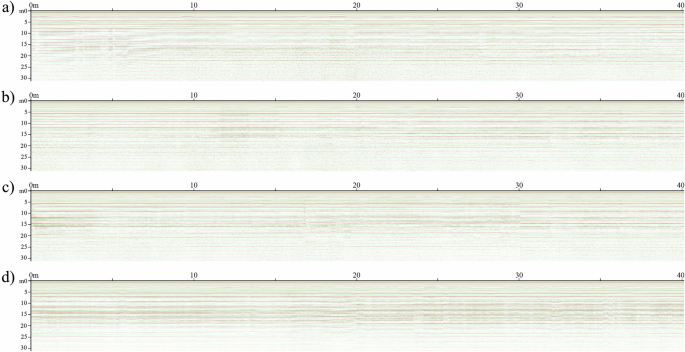

GPR was used to detect structural defects in the tomb. The detection areas were divided according to the regional geological characteristics and the layout of the Yongling Mausoleum (Fig. 4). A frequency of 100 MHz was applied to investigate structural issues such as incomplete formations, cracks, cavities, and water accumulation. The grave mound and foundation were segmented into four zones, and each was scanned from the top to a maximum depth of 43 m. The tomb walls were divided into eight areas, while the floors were sectioned into 9 regions for detailed analysis.

a The red, yellow, green, and light blue lines represented the detection ranges of the first to fourth layers of the grave mound and foundation. b In the detection areas of the tomb, the red lines represented the walls, while the dark blue lines represented the grounds.

Water quality analysis

Two groups of water samples were systematically collected based on the hydrogeological survey (Fig.3). Samples were stored in polyethylene brown bottles that were pre-cleaned with deionized water and rinsed 3 times before collection. Each sample comprised 50 ml of water. The water quality analysis followed the standards outlined in the Code for Investigation of Geotechnical Engineering (GB 50021–2001)36.

Results

Analysis of stone heritage

Based on historical records, the stone artifacts within the Yongling Mausoleum are primarily made of sandstone. Zhang et al. 37 examined the stones used in the Yongling Mausoleum, identifying the rock resources from Jintang County, located several kilometers from Chengdu. The stratigraphy of Jintang County comprises Cretaceous (K) and Jurassic (J) formations. The stone used in the tomb’s construction is sourced from the Longquan Mountains, specifically from the Jurassic Penglai Town Formation (J3p).

The basic physical properties of the source rock and the tombstone materials are presented in Table 6. Due to prolonged weathering, the tombstone materials’ mechanical properties and microstructure have changed.

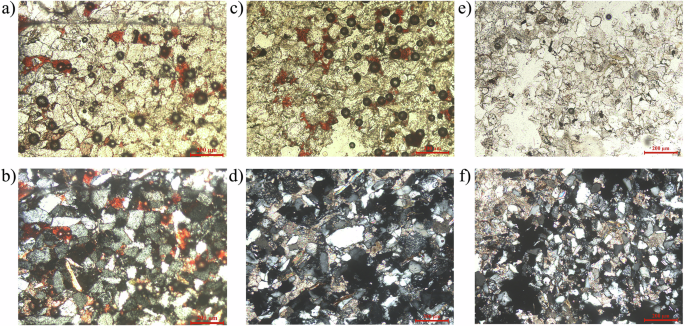

Figure 5 illustrates the optical and petrographic microstructures of the stone samples, with their petrographic features summarized in Table 7. The mineralogical composition of all tested stones from both the postchamber and the coffin platform is consistent, displaying similar proportions. The primary components are quartz, several lithic fragments, K-feldspar, trace amounts of magnetite, and mica. The quartz grains, predominantly angular to subangular and ranging from 0.05 to 0.15 mm in size, are embedded in a calcite matrix that serves as the cement, filling the pores between the framework grains. The primary mineral components of the WJM-01 and WJM-02 consist of 65–70% quartz, 5% calcite, and a certain amount of feldspar and hematite by volume.

a Single polarized view of WJM-01, (b) orthogonally polarized view of WJM-01, (c) single polarized view of WJM-02, (d) orthogonally polarized view of WJM-02, (e) single polarized view of WJM-03, (f) orthogonally polarized view of WJM-03.

This composition indicates specific mechanical properties of sandstone, with calcite playing a significant role in the stone’s integrity. The presence of lithic fragments and feldspar also indicates the geological diversity of the source materials used for the relics.

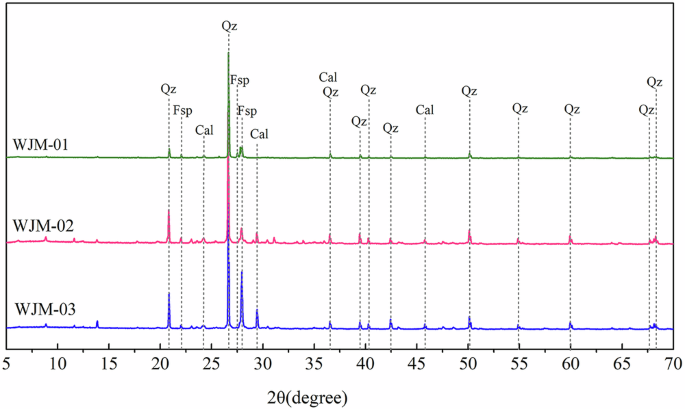

The XRD patterns of the stone samples, shown in Fig. 6, reveal that the sandstones predominantly consist of quartz, calcite, and feldspar. The 2θ values of the samples exhibit a pronounced diffraction peak at 26.5°, corresponding to the strongest diffraction peak of quartz at 27°. Moreover, the diffraction peaks at 26.5° and 28° were consistent with those typically found in feldspar.

Qz represents quartz, Cal represents calcite, and Fsp represents feldspar.

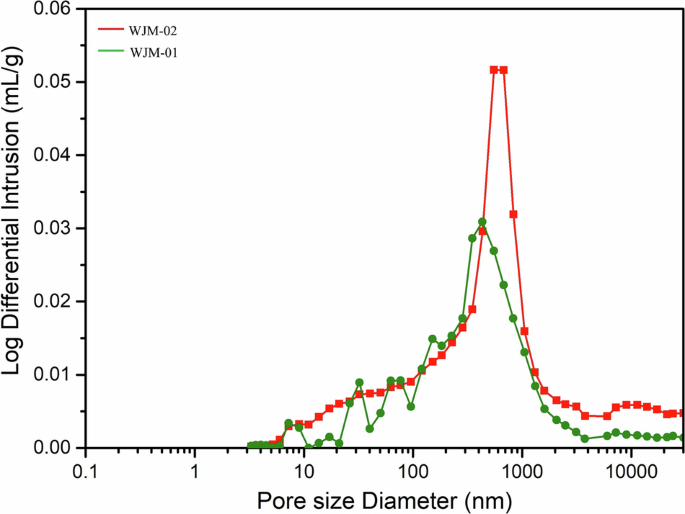

Due to sample size limitations, only the postchamber wall stone sample (WJM-02) met the requirements for MIP. Figure 7 presents the curve from the MIP test, showing the log-differential volume of mercury plotted against pore diameter. The sandstone’s pore size distribution is described as unimodal, as the majority of pore sizes were concentrated within a relatively narrow range. The peak pore diameter on the curve is approximately 670 nm. The sandstone in the postchamber exhibits a pore size range primarily between 370 and 844 nm, with a porosity of 10.70%. The pore size of the red sandstone from the Jintang ranged from 285 to 835 nm, with a porosity of 7.66%. The two are relatively similar.

The red line represented the WJM-02 curve, and the green line represented the WJM-01.

The connectivity, morphology, and pore size distribution of rock pores are critical factors influencing the migration and crystallization of salt solutions38. Most salt crystals are stably located in pores with diameters ranging from 0.5 to 5 μm39. Micropores with diameters smaller than 0.1 μm and 0.2 μm are closely associated with the dry weight loss of the rock. Micropores smaller than 5 μm dominate the absorption of salt solutions and are particularly significant for salt uptake40. The pore size distribution of tomb rock ranges from 370 to 844 nm, which corresponds to the primary range for salt crystallization and facilitates this process. Pores smaller than 100 nm comprise a substantial proportion of the rock, where sodium sulfate crystallization predominates41. This crystallization induces substantial crystallization pressure, acting as a cohesive force that weakens the rock structure.

The cementing material in tombs is predominantly calcite, which is highly susceptible to erosion by acidic gases such as carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and water. These factors induce chemical reactions that weaken the bonding between mineral particles.

Salt composition analysis

Each analytical technique has inherent limitations. SEM provides high-resolution morphological data, while EDS enables the identification of elemental composition and concentration. FTIR and μ‑RS are used to assess chemical bonding, and XRD allows for the characterization of crystalline structures. To overcome the limitations of individual methods and ensure comprehensive identification, a multi-technique approach was employed to analyze the salts extracted from the stone powder samples and surface crystalline salts, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Analysis of extracted salt composition

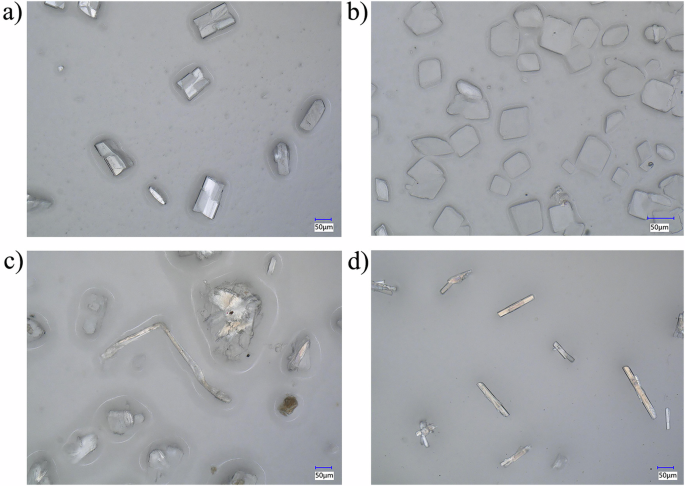

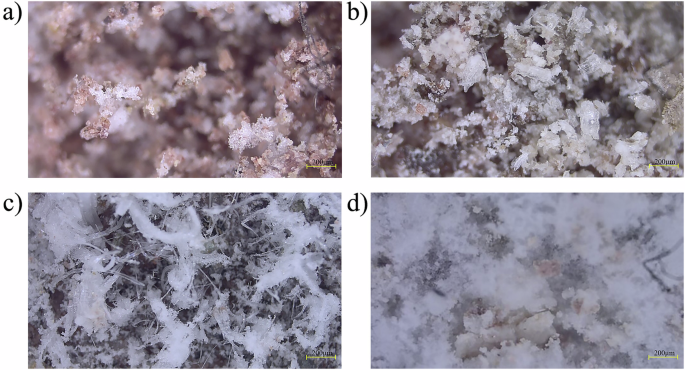

No crystalline salts were observed in the stone powder; the sample was soaked to obtain dissolved ions. IC was used to quantify each ion present, and the results were compared with the concentration of Ca²⁺, as shown in Table 8. The cation content in the stone powder samples, ranked from highest to lowest, was Ca2+ > Na+ > Mg2+ > K+. The anion content was ranked as SO42- > NO3– > Cl–. Under OM, the extracted salts from the stone powders exhibited columnar, needle-shaped, and platy morphologies consistent with the crystalline structures of gypsum (Fig. 8)42.

a WJM-08 (300×), (b) WJM-09 (500×), (c) WJM-10 (300×), (d) WJM-11 (300×).

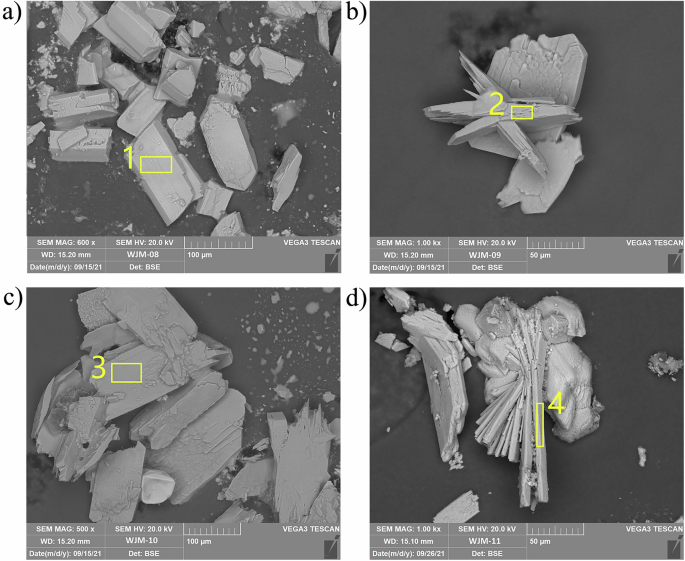

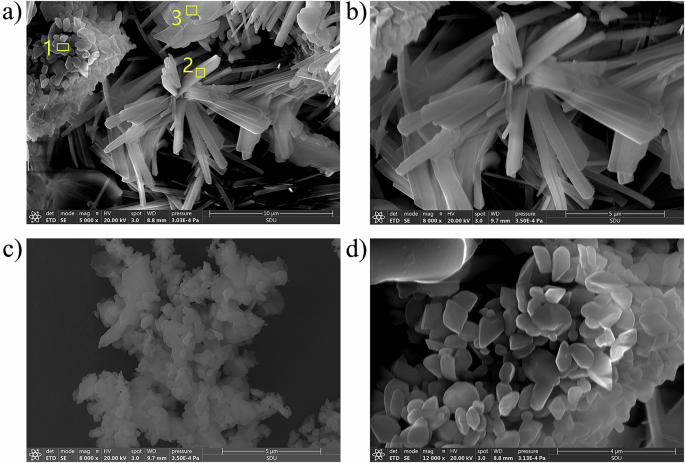

As shown in the SEM micrographs (Fig. 9), the extracted salt from sample WJM-08 exhibited columnar and platy crystals, while the salts from WJM-09 and WJM-10 formed columnar crystals, and WJM-11 displayed rod-shaped crystals. Test points were selected on salts of different shapes, all of which contained the elements Ca, S, and O (Table 9).

a WJM-08 (600×), (b) WJM-09 (1000×), (c) WJM-10 (500×), (d) WJM-11 (1000×).

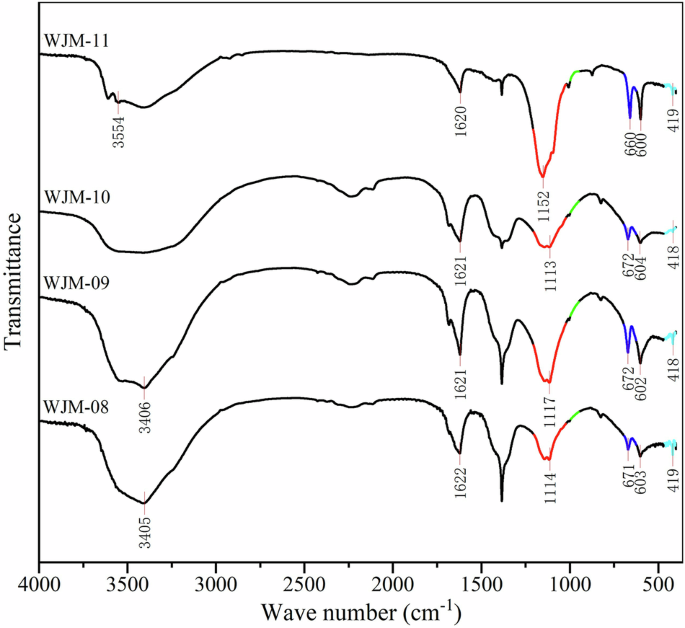

In the spectroscopic investigation, FTIR analysis verified the composition of the extracted salts (Fig. 10). The symmetric bending vibration peak of SO₄²– was observed at 460 cm-1, while the asymmetric bending vibration peak was detected at 620 cm-1 (blue area in Fig. 10). Furthermore, the symmetric stretching vibration peak appeared within the 950–1000 cm-1 range (green area in Fig. 10). The asymmetric stretching vibration peak was located between 1025 and 1210 cm-1(red area in Fig. 10). Compared to anhydrite, the gypsum crystals contain two molecules of crystallization water, as indicated by the O-H vibration peak near ~3500 cm-1. Collectively, these spectral features conclusively identify the extracted salts as gypsum43.

FTIR spectra of the extracted salts.

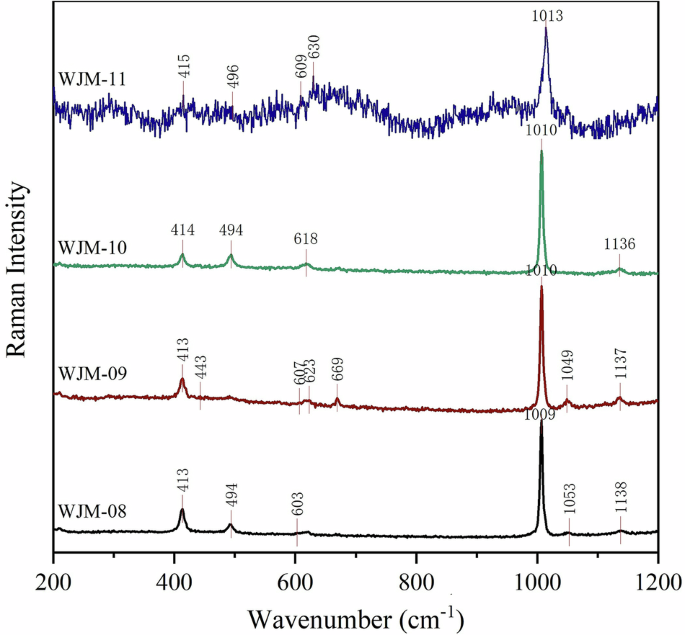

The Raman spectra of the extracted salts (Fig. 11) displayed peaks corresponding to SO42- at 609, 634, 1017, and 1129 cm–1, confirming a strong correlation with the characteristic signals of sulfates44.

Raman spectra of the extracted salts.

Based on the integration of multiple analytical techniques, including morphological observation, elemental analysis, and identification of characteristic peaks, it is evident that the salts extracted from the stone powders of the tomb are predominantly composed of gypsum.

Analysis of surface crystalline salts

Surface crystalline salts on the three sides of the coffin platform and the imperial bed were observed using a portable microscope (Fig. 12). The salts appeared as white crystals distributed across the surfaces of the stone cultural relics or embedded within the sandstone matrix.

a 1st Gigaku on the east side of the coffin platform, (b) 4th Gigaku on the south side of the coffin platform, (c) 7th Gigaku on the west side of the coffin platform, (d) imperial bed.

The microstructures of the crystalline salts were examined using ESEM. As shown in Fig. 13, three primary morphologies were identified in the salts from the 1st Gigaku on the east side of the coffin platform (sample WJM-12): columnar, prismatic, flaky, platy, bow-tie aggregates, and needle-shaped, which were the typical shapes of thenardite and gypsum45,46. EDS analysis revealed that the granular and flaky salts contained the elements Na, S, and O, while the columnar salts also included Ca (Table 10). Based on their morphologies and elemental compositions, the salts from WJM-12 were identified as thenardite and gypsum.

a 5000×, (b) 8000×, (c) 8000×, (d) 12,000×.

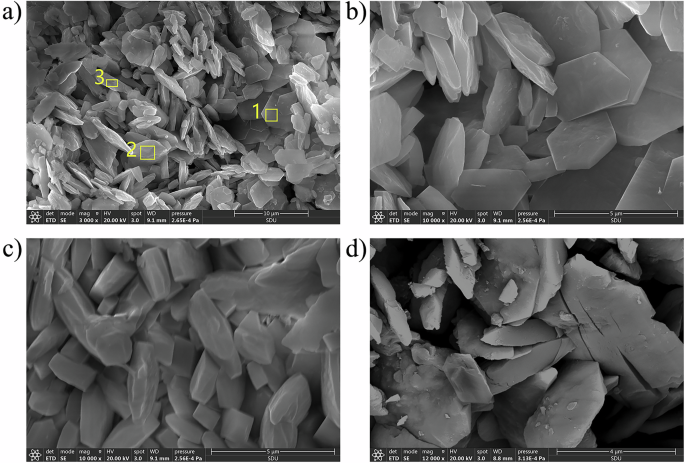

ESEM-EDS analysis was performed on the crystalline salts from the 4th Gigaku on the south side of the coffin platform (sample WJM-13), as illustrated in Fig. 14. The microscopic examination revealed flaky and prismatic morphologies of salts. According to the EDS results (Table 11), these salts comprised approximately 60% oxygen, 20% sulfur, and 20% calcium. The crystalline salts were identified as gypsum based on their morphology and elemental composition.

a 3000×, (b) 10,000×, (c) 10,000×, (d) 12,000×.

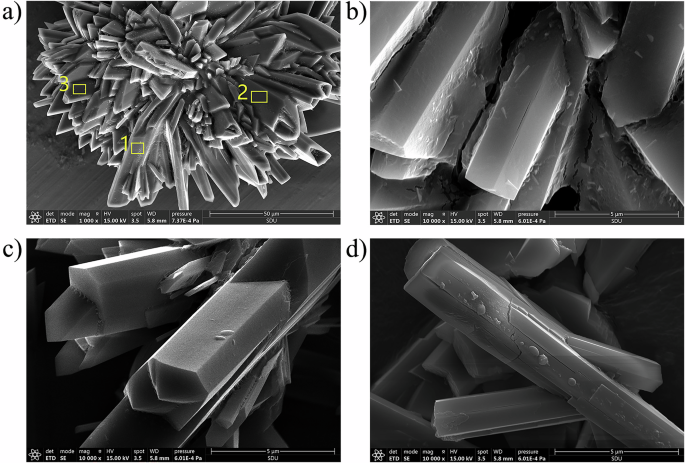

The microscopic morphology of the salt (sample WJM-14) exhibited columnar and swallowtail structures (Fig. 15), which were typical shapes of gypsum47. ESD analysis revealed the elements S, O, and Ca (Table 12). Consequently, the surface crystalline salt on the imperial bed was identified as gypsum.

a 1000×, (b) 10,000×, (c) 10,000×, (d) 10,000×.

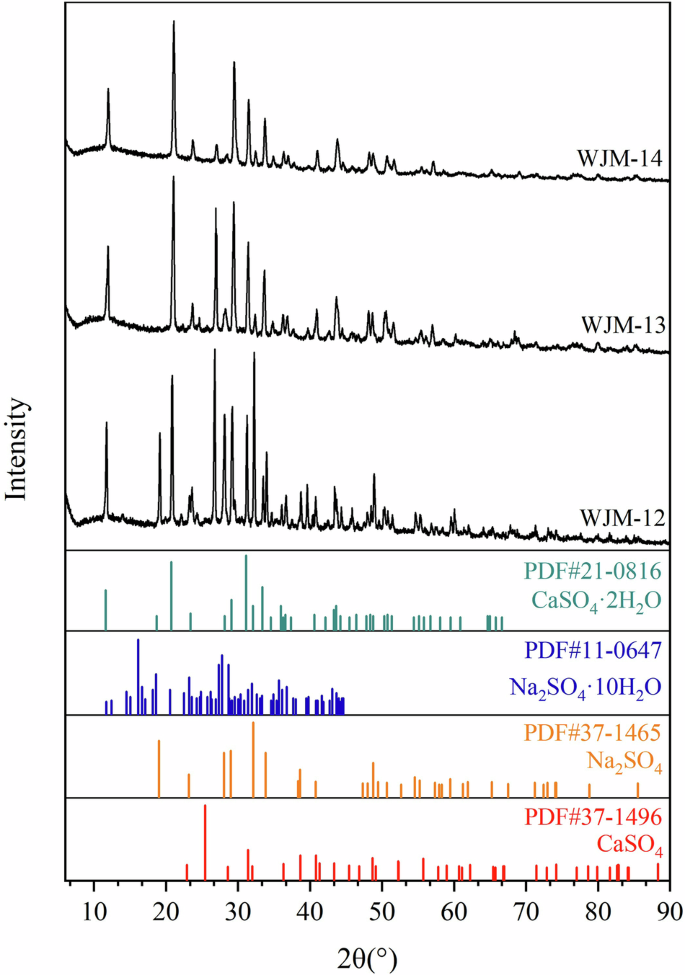

The powder samples were subjected to XRD analysis to confirm the mineral composition of the surface crystalline salts. As shown in Fig. 16, the XRD spectra indicated that the diffraction peaks of salt sample WJM-12 corresponded to the characteristic peaks of both gypsum and thenardite. Meanwhile, samples WJM-13 and WJM-14 exhibited diffraction patterns consistent with gypsum. Mirabilite exhibits pronounced sensitivity to temperature and humidity fluctuations, rendering it susceptible to phase transitions. The environmental conditions during XRD testing differ substantially from those within the tomb, potentially leading to the loss of crystallization water from mirabilite and, consequently, the detection of its anhydrous form. Gypsum is commonly encountered in architectural materials, and previous studies have highlighted its potential for degradation48.

XRD patterns of the surface crystalline salts.

The extracted salts from the stone powders were identified as gypsum through a combination of OM, SEM-EDS, FTIR, and μ-RS analyses. Surface crystalline salts from the stone relics in the tomb were found to contain both gypsum and thenardite based on ESEM-EDS and XRD analyses. Given the environmental differences between the tomb and the testing conditions, mirabilite may have undergone dehydration. Consequently, the study detected thenardite. These findings indicate that the salts contributing to the deterioration of the stone cultural relics in the Yongling Mausoleum are primarily gypsum and sodium sulfate.

Analysis of the sources of salt efflorescence

Examination of the tomb structure

The analysis of sources of salt efflorescence involved a detailed investigation of the tomb’s structural integrity, focusing on potential damage, cracks, holes, and areas of water accumulation within the grave mound, foundation, walls, and surrounding grounds.

Structure of the grave mound

The examination of the grave mound revealed several key observations. As illustrated in the first arc data (Fig. 17), the outer fortress of the tomb was well-maintained, featuring a uniform sepulcher terra layer and a relatively continuous pebble layer. The triple-combined soil layers were intact, exhibiting no significant voids or noticeable water accumulation. This indicates that the structural integrity of the grave mound is generally sound, with no apparent issues contributing to water-related damage or salt efflorescence.

a First arc; (b) Second arc; (c) Third arc; (d) Fourth arc.

Foundation structure

The shallow fill and silt of the foundation on the tomb’s exterior were uniform. The deep pebble layer, with a high moisture content, is saturated. According to the arc data of the foundation (Supplementary Fig. 3), the shallow layers of fill and silt surrounding the tomb exhibited a uniform distribution. The deeper pebble layer exhibited a high moisture content, indicating a state of saturation.

Tomb wall structure

The sandstones and bricks forming the sidewalls of the antechamber exhibited a relatively uniform composition from the inside out (Supplementary Fig. 4a–d). The outer triple-layered soil structure remained intact. Similarly, the walls of the main hall and postchamber (Supplementary Fig. 4e–h) were well-preserved, showing no voids or significant signs of water accumulation.

Tomb ground structure

The ground layers of the tomb, composed of clay, sand, and pebbles, were evenly distributed (Supplementary Fig. 5). The foundation appeared stable, exhibiting uniform composition across the layers and no detectable weak interlayers.

Based on the analysis of the geological radar spectra, the structural integrity of the grave mound, foundation, walls, and grounds was generally uniform, with no significant cracks, voids, or water accumulation detected. Since the repair of the mausoleum in 1989, no external water seepage has been observed within the tomb.

Condensation in the tomb

Between May and September each year, condensation is observed within the tomb, with liquid water droplets forming on the ground, protective glass, the statue of Wang Chien, the imperial bed, and the tomb walls (Fig. 18a–d). This seasonal condensation may significantly contribute to the deterioration of the stone relics due to salt efflorescence and moisture accumulation.

a The ground of the main hall, (b) protective glass, (c) the surface of the imperial bed, (d) the sandstone wall of the postchamber, (e) micrograph of dry stone wall, (f) micrographs of the condensation on the wall.

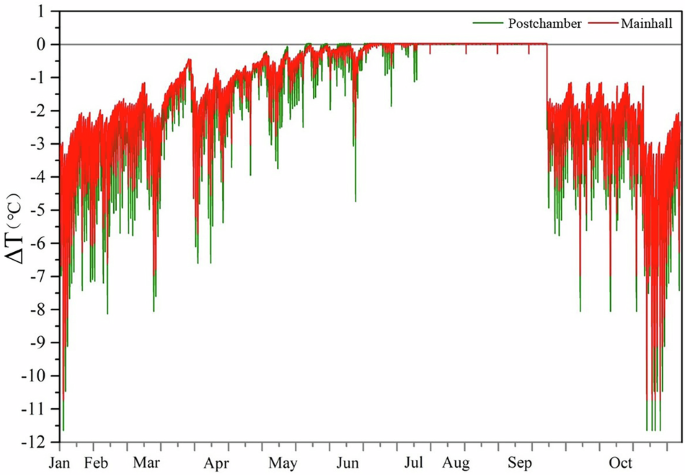

As illustrated in the micrographs (Fig. 18e, f), a thin water film formed by liquid condensation covers the surface of the stone relics. In contrast, areas unaffected by liquid water appeared relatively dry. This difference in moisture levels created a humidity gradient across the surfaces of the stone relics. Temperature sensors were installed in these areas to record the wall and dew-point temperatures, and the temperature differences (ΔT) were plotted (Fig. 19). When the wall temperature exceeded the dew-point temperature, condensation did not occur, as the moisture in the air remained in vapor form rather than condensing into liquid droplets. However, when the dew-point temperature surpassed the wall temperature, the warmer air came into contact with the more extraordinary walls, resulting in condensation.

The red and green lines represented the temperature difference curves of the main hall and postchamber, respectively.

In mid-May, ΔT was above 0 °C for about 10 days, and from June through early September, ΔT consistently remained above 0 °C, indicating significant condensation during this period.

The primary mechanism behind condensation in the tomb stems from the high relative humidity and poor ventilation, inhibiting the dissipation of water vapor. This condition led to supersaturated humidity levels. Due to diurnal temperature fluctuations, the supersaturated moisture condensed on the tomb’s arches, walls, and the surfaces of the stone relics.

Monteith49 introduced the condensation water theory, proposing that condensation occurs when the water vapor content in the air exceeds the saturation vapor pressure at a given surface. Condensation water acts as a medium facilitating three-phase deterioration processes, liquid and solid, on rock surfaces. Under high-moisture conditions, the long-term strength of sandstone decreases by over 40% compared to that under low-moisture conditions50. Fluctuations in humidity and temperature trigger repeated condensation and evaporation cycles, inducing wet-dry processes that weaken the rock mass and accelerate weathering.

Condensation water infiltrates rocks through fractures and pores, reacting with calcite and potassium feldspar minerals. As temperature and humidity decrease from the rock’s surface to its interior, condensation water forms within the rock matrix51, promoting salt dissolution and facilitating its migration into the pore network21,52. Areas experiencing frequent condensation cycles are more susceptible to salt-related damage. Furthermore, excessive tourist activity exacerbates condensation water formation on porous material surfaces, filling nearly 90% of open pores with water53.

Ion types and contents analysis

The tomb’s proximity to several water bodies, including a small river just 93 m south of the site and the Pi River about 3000 m to the north, places it in a region with high groundwater levels. The rivers surrounding the tomb, including the Jinjiang and Huanhua Streams, could potentially influence the salt content in the groundwater and, consequently, the tomb’s local hydrological microenvironment30,33. To the north of the tomb is the Du’an Well, and a catchment well is situated at the tomb’s entrance. These water bodies and wells contribute to the tomb’s susceptibility to groundwater infiltration, which may affect the preservation of the stone relics. Water samples WJM-W1 and WJM-W2, collected from the surrounding environment, were analyzed according to GB 50021-2001 standards. The test results presented in Table 13 provide insights into the ion composition and content, aiding in assessing the potential role of groundwater in the salt deterioration observed in the tomb’s stone relics.

The analysis of water quality indicated that the Du’an Well contains elevated levels of HCO3–, SO42-, Ca2+, and Mg2+, while the catchment well primarily collects rainwater and surface runoff, exhibiting high concentrations of HCO3–, SO42-, CO32-, Ca2+, K+, and Na+.

Historical records reveal that the Yongling Mausoleum was looted between 925 and 933 AD54, followed by restoration efforts led by Meng Zhixiang, the founding emperor of the Late Shu dynasty. According to archeological excavation reports, the tomb was in a state of severe disrepair at the time of its excavation in 1942, with significant water and silt accumulation30. The infiltration of stagnant water during this period facilitated the migration of ions into the stone cultural relics. As the tomb’s microenvironment shifted, the water and salts migrated both within and on the surfaces of the artifacts. Changes in salt concentrations within the solution led to cycles of crystallization and dissolution under varying environmental conditions.

Before the comprehensive restoration efforts in 1989, the tomb experienced extensive water seepage. During the rainy season, water infiltrates through the top and walls, resulting in substantial water accumulation on the ground. Rainwater and irrigation runoff infiltrate the tomb through the grave mound, adversely affecting the stone cultural relics.

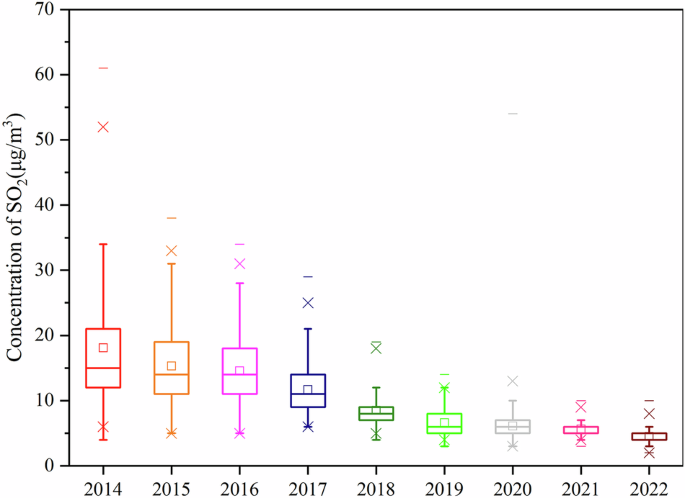

Analysis of atmospheric pollutants

Chengdu is situated at the western edge of the Sichuan, within a designated atmospheric zone of national importance. It is recognized as a convergence point for residential transportation corridors and a region prone to the accumulation of pollutants. The region’s limited ventilation, frequent static winds, and high incidence of temperature inversions result in slow dispersal and prolonged retention of contaminants. The atmospheric conditions are further characterized by a complex mixture of dust, vehicle emissions, and combustion-derived particulate matter55,56. Considering the composition of the stone materials and the types of salts identified within the tomb, SO2 from air pollution was selected as the primary focus of investigation in this study. In this study, data on SO2 from 2014 to 2022 were acquired from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China (http://www.mee.gov.cn/), China National Environmental Monitoring Center (https://www.cnemc.cn/), and a public software platform (https://www.aqistudy.cn/). The harmful gas data collected from the tomb have been analyzed, and the results were provided in the supplementary materials.

As Fig. 20 shows, after implementing environmental control measures, atmospheric SO₂ concentrations have progressively decreased since 2014, from a daily maximum of 63 μg/m³ to a daily maximum of 11 μg/m³. Detailed methodologies and results of CO₂ and SO₂ concentrations in the tomb are provided in the supplementary materials. Notably, after passing through the 29-meter-long tomb passage, SO₂ volume ratio concentrations inside the tomb remained below the detection limit.

Daily SO2 concentration in Chengdu (2014- 2022).

Moreover, The introduction of CO₂ by visitors into the humid environment of the tomb results in peak volume ratio concentrations reaching up to 845 × 10–6, significantly exceeding the typical atmospheric concentration of 400 × 10–6. This elevated CO₂ concentration alters the dynamic equilibrium of the three-phase system gas phase: CO₂, liquid phase: H₂O, solid phase: CaCO₃ in the condensed water, thereby influencing the karstic processes within the tomb. Such changes facilitate the erosion and degradation of the stone, as shown in Eq. (4). Acidic liquids enlarge the pores within the stone, reducing the further absorption of acidic gases. This progressive absorption accelerated the dissolution of the stone’s cementing matrix, leading to an accelerated deterioration of the sandstone.

Analysis of salt efflorescence hazards

Anion content

Based on the Technical Code of Practice for Desalination of Cultural Relics-Part 4: Brick and Stone Relics, the salt content in the effloresced stone powder from the east wall (sample WJM-08) was calculated using the following equation:

where Wt is the content of each ion (%); C is the measured ion concentration (mg/L); V is the volume of liquid to be tested (mL); N is the dilution factor; and G is the mass of the sample involved in the analysis (g).

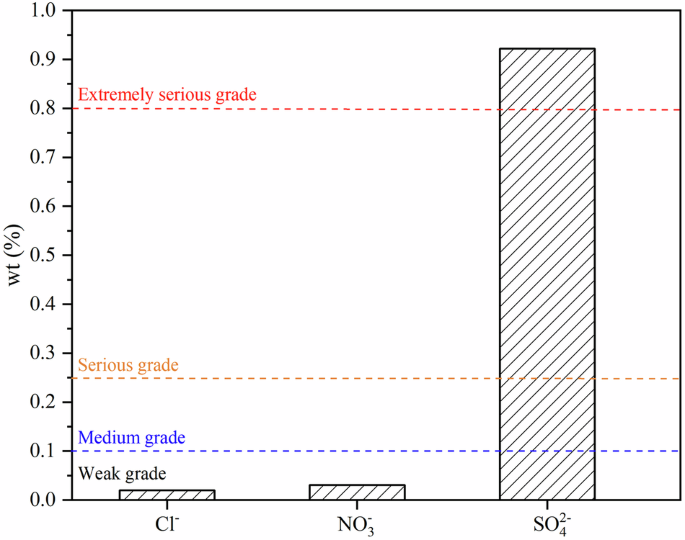

Based on this calculation, the sulfate content of sample WJM-08 was determined to be 0.922% (Fig. 21). According to the evaluation standards for soluble salt hazards in masonry cultural relics, this level of sulfate concentration is classified as extremely severe.

Anion Contents of sample WJM-08.

Due to the cultural and historical importance of the stone relics in the Yongling Masuleum, sampling of the statues was not conducted. However, based on the degree of exfoliation and efflorescence, the salt weathering of the statues appears to be more severe than that of the walls. The sulfate content of the stone cultural relics exceeds 0.922%, indicating a severe condition. Emergency measures must be implemented to mitigate salt accumulation.

Salt hazards

The infiltration of salt solutions is a primary cause of the exfoliation and efflorescence of the stone relics. As microclimatic conditions fluctuate, salts migrate along with moisture and undergo repeated phase transitions between aqueous and crystalline states, leading to significant deterioration57. Situated in natural or semi-natural settings, these archeological sites are often characterized by high humidity, which can accelerate the degradation of heritage materials58. As a result, they are particularly vulnerable to salt weathering, manifesting as efflorescence and crusts composed of mixed soluble salts, primarily in their hydrated forms22,59,60. Regulating microenvironmental temperature and humidity can prevent phase transitions associated with salt weathering or mitigate material deterioration61,62,63,64.

According to monitoring data, the temperature in the tomb fluctuated between 15 and 22.6 °C with minimal variation, while relative humidity ranged from 60% to 100%. At RH levels of 60–75%, mirabilite (Na₂SO₄·10H₂O) is particularly prone to crystallization and subsequent expansion. Additionally, gypsum (CaSO₄·2H₂O) is known to expand under prolonged exposure to high humidity65.

Sampling and analysis revealed that the primary salts involved in the damage are CaSO₄ and Na₂SO₄. The crystallization pressures of these salts under similar conditions ranked as follows: Na2SO4·10H2O < CaSO4·2H2O < Na2SO4 < CaSO466. Sulfates exhibit various hydration phases during precipitation, each contributing differently to stone degradation.

Among these salts, Na2SO4 is one of the most destructive due to its significant volume changes during solution-crystal transitions, its various crystallization phases, and the complexity of its crystallization process. Sodium sulfate’s potent destructive impact on porous materials has garnered extensive attention in conservation research.

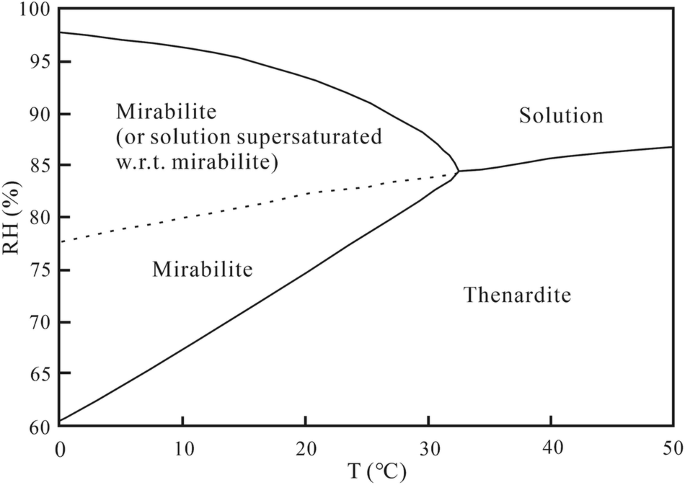

At temperatures below 22 °C, Na2SO4 transitions to Na2SO4·7H2O. As temperatures rise between 22 °C and 32.4 °C, the salt first forms anhydrous Na2SO4, which subsequently converts to Na2SO4·10H2O. Above 32.4 °C, Na2SO4 crystallizes into an orthorhombic structure67. The crystallization behavior of Na2SO4 under varying temperature and RH conditions is best understood through phase diagrams. Steiger et al. 68 revise the Na2SO4-H2O phase diagram, as illustrated in Fig. 22. At 20 °C, mirabilite forms when the RH exceeds 75%. As humidity decreases and evaporation rates rise, the formation of thenardite becomes predominant within porous materials. This phase transition generates substantial crystallization pressure, which exerts stress on pore walls, ultimately leading to the deterioration of the stone’s porous structure66.

The continuous lines indicate the boundaries of the stable phases. The discontinuous line corresponds to a solution in metastable equilibrium with respect to thenardite and supersaturated with respect to mirabilite69.

These precipitation processes generate significant crystallization pressure and substantial hydration pressure. Winkler16 calculated the hydration pressure associated with the transformation of Na2SO4 to Na2SO4·10H2O under varying temperatures and RH conditions. The combined effects of crystallization and hydration exert significant mechanical stress on the porous structure of the stone, intensifying its degradation and accelerating the weathering process.

Price et al.25 measured the volumetric differences between the hydrate phases of sodium sulfate, finding that the volume of mirabilite is 314% larger than that of thenardite17,69. This significant increase in molar volume fills the pore space more extensively, creating a larger contact area with the pore walls and intensifying stress propagation. Na2SO4·10H2O is particularly destructive during the crystallization stage25. Due to its high sensitivity to humidity, Na2SO4 readily absorbs or loses water as humidity fluctuates, with these phase transitions often leading to volume expansion or contraction, contributing to stone deterioration. However, some studies suggest that thenardite can crystallize directly from the solution rather than solely through the dehydration of mirabilite45.

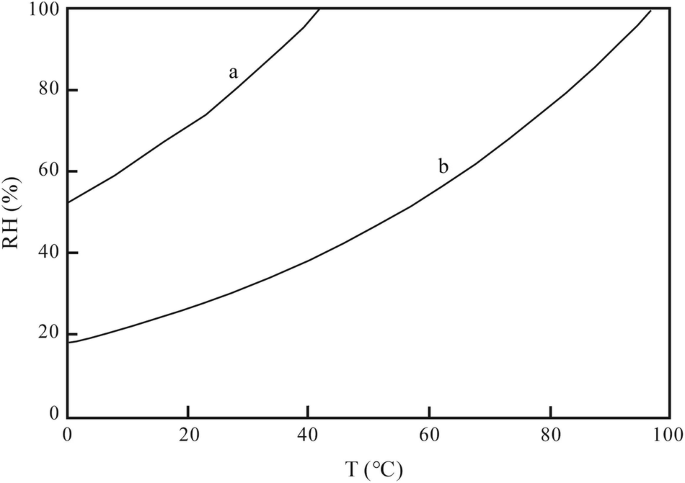

Calcium sulfate exists in three distinct mineral forms, classified by their degree of hydration: gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O), hemihydrate gypsum (CaSO4·0.5H2O), and anhydrite (CaSO4). The phase diagram for the CaSO4-H2O system, depicting relative humidity versus temperature, is shown in Fig. 23.

CaSO4-H2O in a plot of relative humidity versus temperature, where: (a) gypsum-anhydrite equilibrium curve, (b) gypsum–hemihydrate equilibrium curve76.

At 8 °C, with a supersaturation degree of 2, CaSO4 crystals exert more significant crystallization pressure than CaSO4·2H2O. At 20 °C, the hydration of CaSO4·0.5H2O resulted in the formation of CaSO4·2H2O, with a significant increase in hydration pressure as humidity levels rose. When the RH reached 100%, the hydration pressure generated nearly doubled that at 60%16. The extent of damage caused by calcium sulfate is primarily influenced by RH, as higher humidity promotes crystallization within the stone, leading to increased deterioration70. Under optimal conditions, the maximum hydration pressure generated by converting CaSO4·0.5H2O to CaSO4·2H2O can reach up to 2190 kPa16. In a humid environment, CaSO4·2H2O undergoes a volume expansion of up to 63%, while dehydration to form anhydrite results in a maximum volume reduction of 39%. The combined effects of crystallization pressure, hydration pressure, and phase-related volume changes contribute to the structural damage of stone relics.

The combination of humidity and temperature inside the tomb plays a critical role in the movement of water and salts, which accelerates salt weathering. Even with minimal temperature fluctuations, variations in RH can activate different sulfate hydration reactions, leading to the exfoliation and efflorescence of the stone relics. In addition, evaporation is a critical factor in salt weathering, as it influences both the location and morphology of crystallized salts. Under otherwise comparable conditions, higher airflow velocities can accelerate evaporation, preventing the salt solution from reaching the rock surface and causing evaporation below it. A secondary condensation-evaporation cycle may result in the dissolution of pre-formed sodium sulfate crystals, while the subsequent precipitation of mirabilite crystals can generate additional material degradation. The Yongling Mausoleum has low airflow velocity (with airflow velocities ranging from 0 to 0.30 m/s) and high relative humidity. In such conditions, the evaporation rate of salt solutions is relatively slow, leading to the formation of salt efflorescences on the rock surface. These efflorescences are less destructive compared to subefflorescences.

Notably, areas characterized by extremely low temperatures and high RH are particularly vulnerable to salt crystallization and frequent hydration changes, resulting in increased stone exfoliation and degradation. While addressing visible signs of deterioration, such as exfoliation and efflorescence, is essential, monitoring the microenvironment in these high-risk zones is equally important. Implementing effective climate control strategies is crucial for preventing further damage and preserving the integrity of the stone relics over time.

Water hazards

Sandstone is composed of mineral particles bound by intergranular cement, and the presence of water significantly impacts its structural integrity through lubrication and softening effects. High water content reacts with the calcareous cement in sandstone, weakening the bond between mineral particles and expanding internal cracks. This expansion increases internal pressure, reducing the stone’s mechanical properties71. For instance, the K-feldspar in the sandstone of the Yongling Mausoleum hydrolyzes with condensate to form kaolin, causing a 54.6% volume change72, resulting in the formation of pores (Eq. 6):

Yang et al.73 studied the mechanical properties of sandstone in the Yungang Grottoes and found that the strength of medium coarse-grained sandstone with high water content was reduced by 44.31% compared to sandstone with low water content. Similarly, Cui et al.74 conducted dry-wet cycle experiments on sandstone from the Helankou rock painting site, using distilled water and various salt solutions. Their findings indicated that while distilled water was less damaging than salt solutions, it still reduced the mechanical strength of sandstone by approximately 2%.

The water inside the pores acts as a carrier for saline liquid and transports it upwards75. When the salt solution enters the porous material, the internal salt concentration increases and the saturated vapor pressure of the salt solution becomes lower than that of pure water, leading to a higher tendency to condense water vapor from the environment. After the internal salt concentration and the water content of the porous material increase, the capillary action is further enhanced. This constitutes a dynamic process of salt weathering.

In addition to weakening mechanical properties, water also plays a crucial role in dissolving and transporting salts within the stone. Capillary action and infiltration are the primary mechanisms through which dissolved salts penetrate the stone relics6. Once inside the porous material, the salt solution increases internal salt concentration, lowering the saturated vapor pressure of the solution compared to pure water. This leads to a greater tendency for the stone to absorb water vapor from the surrounding environment. As salt concentration and water content rise, capillary action is further enhanced, creating a dynamic process that accelerates salt weathering.

Two approaches can be employed to address the structural issues, salt sources, and the geological and hydrological environment affecting the Yongling Mausoleum: environmental improvement and desalination measures. Drainage channels can be installed around the tomb to promptly direct rainwater runoff, reducing the impact of external humidity on the tomb chamber. When groundwater levels exceed a critical threshold, automatic pumping systems can be used to lower the water table, mitigating the effects of groundwater on the tomb. Dehumidifiers can be activated based on the RH levels within the tomb to reduce condensation and minimize the migration and crystallization of salts. Additionally, mechanical methods should be used to remove visible crystalline salts from the surface, followed by the poultice method to remove both surface and internal salts of the stone cultural relics.

Discussion

This study examined the composition of stone materials, the types and sources of salts, and their associated deterioration mechanisms in the Yongling Mausoleum. The stone cultural relics in the tomb were primarily composed of quartz, K-feldspar, and calcite, with no harmful salts initially detected. However, comprehensive analysis utilizing OM, SEM-EDS, IC, FTIR, and μ-RS identified gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) as the predominant salt contributing to exfoliation and efflorescence. Surface crystalline salts collected from the coffin platform and imperial bed were identified as a mixture of CaSO4·2H2O and Na2SO4 based on morphological and phase analyses. This study improved the precision of salt composition analysis in relation to stone deterioration by integrating macroscopic and microscopic techniques, including deterioration pattern analysis, chemical composition, microstructural analysis, and functional group identification. However, due to environmental discrepancies between laboratory conditions and the tomb, there are certain challenges in the identification of crystalline salt hydrates, particularly sodium sulfate salts with various hydration states.

Expanding on previous research, this study provides a more comprehensive analysis of salt sources by integrating factors such as the tomb’s structural characteristics, archeological excavations, historical conservation efforts, surrounding water quality, atmospheric pollutants, and evidence of tomb robbery. This comprehensive investigation, integrating temporal, spatial, macroscopic, and microscopic perspectives, reveals that salt ions primarily originated from historical water accumulation, water seepage, and atmospheric SO₂ pollution. Under the environmental conditions of the tomb, characterized by temperatures of 15–20 °C and RH levels of 60%-100%, the crystallization pressure and hydration pressure contributed to the deterioration of stone relics. High RH also accelerated the hydrolysis of K-feldspar, further weakening the mechanical properties of the sandstone. Notably, the combined effects of salt and moisture led to the progressive exfoliation and efflorescence observed on the stone relics. Crucially, the sulfate content in the tomb’s stone relics exceeds 0.8%, reaching the threshold for severe deterioration and underscoring the urgent need for conservation measures. In addition, having identified the destructive role of crystalline salts and condensate water in the tomb’s microenvironment, this study proposes strategies for environmental improvement and desalination.

Despite these advancements, limitations in conservation efforts and sample collection have hindered a comprehensive understanding of the crystalline salt distribution and migration from the stone surface to its interior. Additionally, investigating stone degradation trends in relation to microenvironmental factors, mixed salt compositions, and sandstone properties remains a critical avenue for future research on salt weathering mechanisms. Further research is needed to deepen our understanding of these processes.

Using an integrative, multi-method analytical approach, this study effectively identified the types of salts, traced their sources, and elucidated the mechanisms of degradation. The findings provide a scientific foundation for future conservation strategies aimed at mitigating the deterioration of stone relics. Moreover, the analytical framework employed in this study offers a useful reference for investigating salt weathering processes at other archeological sites.

Responses