Identification of yellow lake pigments in paintings by Rembrandt and Vermeer: the state of the art revisited

Introduction

Analysis of artists’ materials can allow researchers to gain geographical and temporal information about the origins of an artwork, contribute to art historical research, inform conservation treatments and preservation requirements, and understand how the current appearance of a work may differ from the original. In the case of paintings, the identification of both inorganic and organic pigments can provide critical information. The organic pigments also known as lakes are formed by precipitating a water-soluble dye onto an inorganic support to form an insoluble pigment. Red and yellow lakes are the most important categories of natural organic pigments used in works of art. Despite advances in material analysis in recent decades, natural lakes, particularly yellows, remain a challenge to detect. This is due to a combination of factors, including the structural complexity and poor stability of organic colorants, the need for invasive sampling, and the availability of instrumentation.

Inorganic pigments can be readily identified using non-invasive techniques, such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF), Raman spectroscopy, or X-ray diffraction (XRD)1,2,3,4. These techniques can be performed without sampling or making contact with an artwork. When it is possible to take samples, scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) offers additional information without consumption of the sample, allowing for multiple rounds of analysis using different techniques over the course of years from a single, microscopic fragment5,6,7,8. This has resulted in a corpus of knowledge regarding the availability and use of inorganic pigments by artists over centuries.

In the case of the synthetic organic pigments that started to be developed by the end of the 19th century, analysis by Raman spectroscopy and XRD is possible in most cases9,10,11,12. These non-invasive techniques are typically less effective for the study of natural organic pigments because the strong fluorescence of natural organic chromophores often overwhelms their weak Raman signal, and they tend to have a low degree of crystallinity for XRD analysis. A few organic colorants contain elements such as bromine that can be directly mapped using XRF, but most of these colorants are synthetic rather than naturally occurring13,14,15. Indirect evidence of the presence of organic lakes may be obtained by identifying the substrate on which the dyestuff was precipitated, though not the dyestuff itself. For example, using XRF elemental analysis, the presence of lake pigments is often inferred from the presence of calcium (indicating the use of calcium carbonate, or chalk)16,17,18,19,20, potassium (indicating the use of potassium carbonate, or potash)2,21,22, aluminum (indicating the use of alumina or potash alum)23, or other inorganic compounds24,25. In addition to the substrates, secondary reaction products caused by interaction of lake pigments with their substrate and surrounding materials have been used to identify areas where lakes have been used4.

In organic colorants, the substitution of a single atom or bond can result in an entirely different molecule, making the detection of minor differences both critical for their identification and a major analytical challenge. UV-visible absorption spectroscopy, fluorescence spectroscopy, fiber optics reflectance spectroscopy (FORS)26, and multispectral and hyperspectral imaging methods27 do not require sampling; however, they lack the specificity necessary to identify certain colorants, particularly natural yellow dyes or pigments. In contrast, micro-sampling techniques—which include surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)28,29,30,31, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)29,30,31,32,33,34, and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)35—provide additional information, even down to the molecular level. Therefore, one must typically balance the disadvantages of sampling with the advanced analytical potential of micro-sampling techniques.

Even when taking samples is possible, organic colorant analysis can present several challenges. The high tinting strength of organic colorants is valuable to the artist but is a detriment to the scientist, leaving fewer molecules available for analysis. This issue is compounded by the light sensitivity of many organic colorants, which further reduces the concentration of molecules36,37. Several researchers have observed that the light stability of an organic lake is highly dependent on its substrate, medium, and preparation16,38,39. For example, from the late fourteenth century until at least the early seventeenth century, a common practice for producing red lakes involved extraction of the colorant from dyed cloth shearings. This practice produced pigments with increased light sensitivity relative to those prepared directly from the pure dyestuff16. All these issues are enhanced when dealing with yellow organic lakes, which tend to be less stable than their red counterparts and their sources more chemically similar16,25,40,41.

In some cases, two yellow colorant sources can have nearly identical compositions, save for a single, minor marker compound. For example, weld (Reseda luteola) and dyer’s broom (Genista tinctoria) are often differentiated by the presence of genistein: a flavonoid found only in dyer’s broom40. Genistein is also a structural isomer of apigenin, the latter of which is produced by both species42,43,44. It is therefore important for definitive identification to classify minor components, a task to which HPLC and LC-MS are uniquely suited. Though non-invasive methods such as FORS or non-destructive techniques such as SERS can be powerful approaches for the identification of many colorants, these techniques are typically not specific enough to distinguish between yellow lakes, particularly when mixtures of colorants are present, though there are a few exceptions28,45.

As a result, chromatographic techniques such as HPLC or LC-MS are most reliable for analysis of yellow dyes and pigments, although the sample size required for these techniques is relatively larger (~500 µm2 sample). One must therefore perform cost-benefit analysis to determine whether the information that stands to be gained is worth sampling from a precious object. Recently, technological improvements that allow for reduced sample sizes and the increased availability of high-resolution instrumentation have opened the door to analysis (or reanalysis) of yellow lakes that could not be identified previously.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) are two of the most celebrated Dutch painters of the 17th century, known for their skillful use of light and shadow, with Rembrandt famous for his portraits and dramatic compositions, and Vermeer renowned for his delicate depictions of domestic life and exceptional use of color and light. Rembrandt was born in 1606 and produced paintings from the late 1620’s until his death in 1669, and Vermeer was born in 1632 and produced paintings from the early 1650’s until his death in 1675. Both red and yellow lakes in paintings by these artists have been of interest for decades.

In his in-depth study of Vermeer’s grounds and pigments, H. Kühn identified a madder lake in two paintings, Christ in the House of Mary and Martha and A Maid Asleep, using infrared spectroscopy and chemical tests46. He also suggested Indian yellow had been used in the curtain of Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance, but the sample was later determined to have been taken from restoration overpaint in the painting’s edge and therefore not original to Vermeer47. In 1998, K. Groen et al. identified luteolin, the main colorant of weld, combined with an indigotin-containing colorant, in the background of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring using HPLC33. In 2018, re-analysis with HPLC of the samples from Girl with a Pearl Earring detected luteolin along with additional colorants found in weld, supporting Groen’s previous identification34. Using spectral imaging techniques, J. Delaney et al. mapped pigments in Girl with a Pearl Earring, detecting a red lake in the girl’s face and headscarf2. Based on FORS measurements, they proposed that an insect-based lake, such as cochineal or lac, may have been used.

J. Wouters identified a red lake as cochineal based on the presence of carminic acid in Rembrandt’s Susanna. A yellow lake could not be identified, but the detection of chalk in the foliage layer suggested the presence of a faded organic yellow20. J. Kirby performed extensive analysis of the red lakes in Rembrandt paintings over decades. Using spectrophotometric analyses, she identified a colorant derived from a scale insect source in the National Gallery’s Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels and Self-portrait aged 6348, and using HPLC she detected cochineal in A Young Man and a Girl Playing Cards32. A sample taken from the red tablecloth in Aristotle with a Bust of Homer was analyzed by Kirby in 1995, who reported that the yellow lake might be weld but acknowledged that a Rhamnus species could have been used instead49. In 2014, N. Shibayama identified the red lake in the tablecloth as cochineal but could not detect the yellow lake by HPLC50. Recently, D.A. Peggie and J. Kirby reexamined several Rembrandt paintings at the National Gallery, London using HPLC, identifying cochineal used on its own and in combination with other red lakes such as madder and brazilwood51. The glaze on the plum-colored coat in Self Portrait at the Age of 63 was found to contain cochineal and madder combined with a yellow lake, proposed to be buckthorn, although a definitive identification was not made. To the best of our knowledge, there has not yet been an unequivocal identification of a yellow lake in a painting by Rembrandt.

This study focuses on areas of three paintings where yellow lakes were believed to be present, but not identified: the backgrounds in Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid and Study of a Young Woman, and a deep shadow in Rembrandt’s Aristotle with a Bust of Homer. HPLC-qToF-MS was used to identify the colorants in unmounted samples that had been stored in the archives of the Paintings Conservation Department at the Metropolitan Museum, allowing us to avoid additional sampling. The goals of the present study were multifaceted: to firmly identify the yellow lakes, to better understand the original appearance of the paint passages where the yellow lakes were used, and to gain further insight into the artistic practices of Vermeer and Rembrandt.

Experimental methods

Samples

The samples from the three paintings were stored in the archives of the Paintings Conservation Department at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met), so no additional sampling was performed for the present study. The locations on the paintings where these samples were taken are indicated in Fig. 1A (Mistress and Maid, Johannes Vermeer), Fig. 5 (Study of a Young Woman, Johannes Vermeer), and Fig. 7A (Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, Rembrandt). Reference samples of carmine nacarat and weld lake were purchased from Kremer Pigmente (New York, NY, USA) and mixed with linseed oil and painted over glass slides for preparation of mockups. A reference of wool dyed with Persian berries from the Schweppe collection was used as a reference for a Rhamnus species.

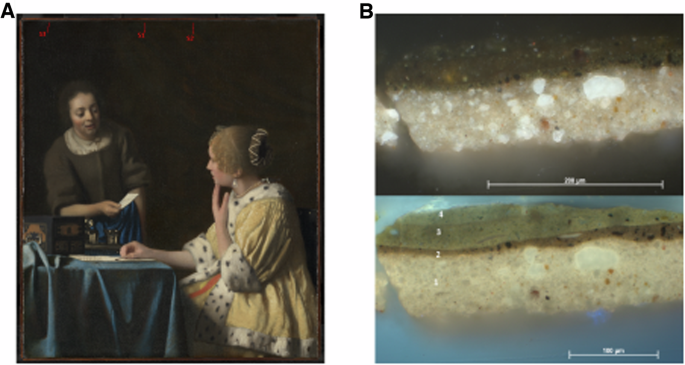

A The red arrows show the approximate locations of microsamples S1, S2, and S3. Image is in the Public Domain. B Photomicrograph of a cross-section of sample S2, taken with visible (top) and with UV illumination (bottom), original magnification ×400. Paint layers 3 and 4 in the photomicrograph taken with UV illumination correspond to the paint of the curtain. All images were adapted from figures first published in D. Mahon, S.A. Centeno, M. Iacono, F. Carό, H. Stege, A. Obermeier. ‘Johannes Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid: New Discoveries Cast Light on Changes to the Composition and the Discoloration of Some Paint Passages.’ Heritage Science, 2020, 8:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00375-2.

Sample extraction

HCl extraction method (adapted from Wouters and Verhecken, 1989)52

Pigment samples were placed in a test tube, to which 20 μL of 6 N HCl in methanol were added. The solution was heated for 10 min at 90–100 °C, then cooled and dried for 30 min in a Genevac EZ-2 4.0 vacuum concentrator to remove the HCl (using the “aqueous HCl” method of the Genevac vacuum concentrator). 25 μL methanol were added and the evaporation procedure was repeated. 25 μL methanol were added for a second time and dried for 30 min using the “low boiling point” method of the Genevac vacuum concentrator.

BF3-MeOH method (adapted from Kirby and White, 1996)32

Pigment or reference samples were placed in a Reacti-Vial™ Small Reaction Vial, to which 20 μL of a 4% BF3-MeOH solution were added. The vial was sonicated for 10 min and allowed to react at room temperature overnight. Then 25 μL of methanol were added and the residue was transferred to a glass test tube. After rinsing the vial with an additional 25 μL methanol, the test tube was dried in a Genevac vacuum concentrator (using the “low boiling point” method) for an hour. 50 μL methanol was added and evaporated again with the same method, this time for 30 min.

Reconstitution method (both extractions)

The dried extract was reconstituted as follows: To the tube containing the dried pigment extract, 2 μL dimethylformamide (DMF) was added, followed by 8 μL mobile phase B (MPB, 0.1% formic acid in methanol/acetonitrile (1:1, v/v)) and 10 μL mobile phase A (MPA, 0.1% formic acid in Milli-Q water) (with each addition of solvent followed by brief vortexing of the sample), yielding a solution of DMF/MPB/MPA with a 1:4:5 ratio (v/v/v). The filter of an Ultrafree-MC centrifugal filter (0.2 µm pore size, hydrophilic PTFE membrane, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) was wetted with 4 μL of reconstitution solution and the extract was added. The tube was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was transferred into a 0.2 mL micro-insert for injection (8 µL) into the LC-MS system for analysis in negative ionization mode. To prepare for analysis of the opposite polarity, the centrifugal filter was again wetted with 4 μL reconstitution solution and transferred into a clean 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. 10 µL of reconstitution solution was added to the micro-insert and vortexed. The contents of the insert were then transferred to the centrifugal filter, which was again centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min and the supernatant was transferred into a new micro-insert for injection in positive ionization mode.

High-performance liquid chromatography electrospray ionization, quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-qToF-MS)

The HPLC-ESI-qToF-MS system consists of a Bruker Impact II quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization source (Billerica, MA) and a NexeraXR high-performance liquid chromatograph with two LC-20ADxr HPLC pumps, HPLC gradient mixer, SPDM30A diode array detector, CTO-20AC column oven, DGU-20A5R degassing unit, SIL-20ACxr autosampler, and CBS-20A communications bus module (Shimadzu, Columbia MD).

A Zorbax SB-C18 reversed-phase column (3.5 μm-particle size, 2.1 mm I.D. x 150.0 mm, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used with a Zorbax SB-C18 guard column (3.5 μm-particle size, 2.0 mm I.D. x 15.0 mm, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). To the guard column was attached a pre-filter (Upchurch ultra-low volume pre-column filter with 0.5 μm stainless steel frit, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO). Chromatography was performed at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min and a column temperature of 40 °C, with a gradient of 0.1% formic acid in Milli-Q water (mobile phase A) and 0.1% formic acid in methanol/acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) (mobile phase B). The gradient system was as follows: initial conditions 90% A for 1 min, a linear slope from 90% to 60% A over 6 min, a second linear slope from 60% to 1% A over 23 min, holding at 1% A over 3 min, then a linear slope to return to 90% A over 1 min, and holding at 90% A for 18 min, for a total run time of 52 min.

Internal calibration of the mass spectrometer is performed daily using 10 mM sodium formate solution. Sodium formate clusters were formed using a mixture of Milli-Q water, 2-propanol, formic acid, and 1 M sodium hydroxide (250:250:5:1, v/v/v/v). ESI operating parameters were as follows: capillary voltage 4500 V, dry gas 8.0 L/min, dry heater 220 °C, nebulizer 1.8 Bar. Operation of the HPLC and MS systems was performed using Compass otofControl Version 6.3.106 and Compass Hystar Version 6.2.1.13. Data analysis was performed using Compass DataAnalysis software Version 6.1. Chromatograms were smoothed using a gaussian algorithm, with a width of 2 s.

Results and discussion

HPLC-qToF-MS analysis of Mistress and Maid, Johannes Vermeer, ca. 1666-67

A previous study of Mistress and Maid using macro-X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (MA-XRF) revealed figural elements in the background, likely depicting a tapestry or painting that Vermeer had painted over with a curtain8. The paint in the curtain was determined to contain a copper-based pigment by MA-XRF. Raman spectroscopy and SEM-EDS analyses of three paint cross-sections taken from the curtain in the top edge of the painting (S1, S2, and S3, Fig. 1A) showed—in addition to a copper-based pigment, such as a verdigris, copper oleate, or copper resinate—indigo, abundant calcium carbonate in the form of chalk, some gypsum, and particles of lead white. This lead researchers to propose that the curtain was initially a translucent dark green color, which has since discolored to a dark brown8. The presence of chalk was suspected to be related to a yellow lake; however, analysis of the lake was not performed at the time. Sample fragments left after these three cross-sections were prepared, corresponding to the locations shown in Fig. 1A, were used in the present study to identify the yellow lake. Photomicrographs of the cross-section corresponding to sample S2 are presented in Fig. 1B.

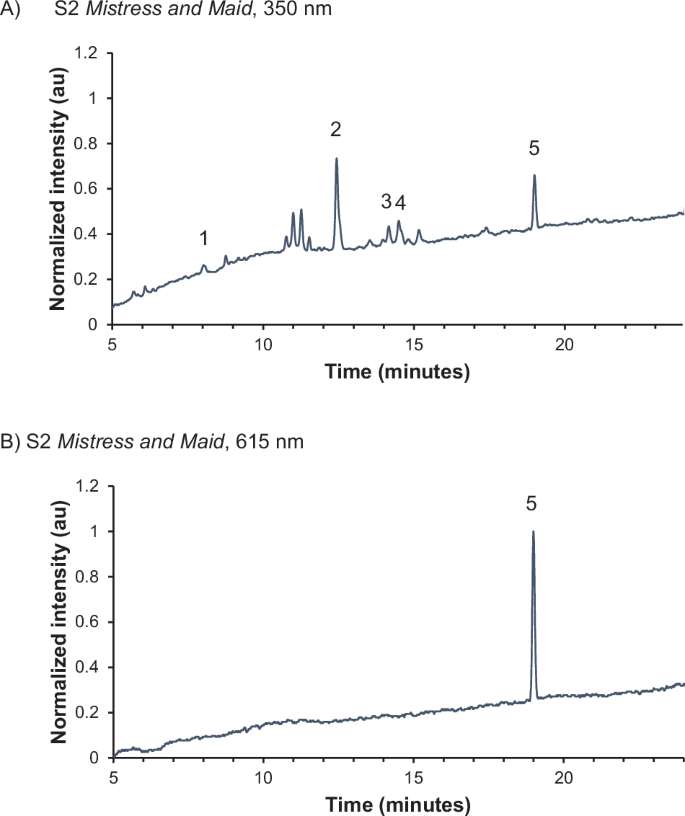

Extraction of the three samples from Mistress and Maid was initially attempted with boron trifluoride, which did not allow for identification of the yellow lake. Extraction with HCl, a strong acid, was proposed as an alternative that might allow for more aggressive extraction of the pigment, leading to a greater concentration of molecules in solution and possible improved detection. HPLC-qToF-MS analysis of the three samples after HCl extraction confirmed the use of an indigotin-containing colorant. Though analytical techniques cannot currently differentiate between sources of indigotin, the indigotin source in Mistress and Maid is likely Indian indigo (Indigofera tinctoria), which replaced woad (Isatis tinctoria) as the major blue colorant in Europe beginning in the mid-sixteenth century53. S1 and S2 both contain luteolin (12.4 min), a common flavonoid. Apigenin (14.2 min) and chrysoeriol (14.6 min), two additional flavonoid components, were detected in S2 only (Fig. 2A, B). No flavonoids were detected in S3, possibly due to the small sample size.

A 350 nm and B 615 nm. Isatin (1), luteolin (2), apigenin (3), chrysoeriol (4), and indigotin (5) are identified.

The detection of luteolin in both S1 and S2 and apigenin and chrysoeriol44 in S2 indicates the yellow lake may derive from Reseda luteola (weld), one of the most important natural yellow colorants in Europe during this period. Analysis of a reference of weld lake extracted with HCl revealed luteolin, apigenin, and chrysoeriol as the major colorants (Figs. 3 and 4). The full characterization of both the HCl-extracted samples and the reference material is given in Table 1. No glycosides were detected in any of the materials analyzed, likely due to the extraction conditions, which can result in cleavage of the glycosidic bond.

Luteolin (2), apigenin (3), and chrysoeriol (4) are identified.

Major colorants present in a reference sample of a lake pigment from Reseda luteola extracted with HCl.

HPLC-qToF-MS analysis of Study of a Young Woman, Johannes Vermeer, ca. 1665-67

Study of a Young Woman (ca.1665–67, Fig. 5) was not included in H. Kühn’s investigation of paintings by Vermeer46 because the work was in a private collection at the time. More recently, D. Mahon, S.A. Centeno and F. Carό examined and analyzed the painting using X-radiography, infrared reflectography, and MA-XRF. The information obtained from the non-invasive techniques mentioned was complemented by examination and analysis using optical microscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and SEM-EDS of samples stored in the archives of the Paintings Conservation Department at The Met. In this previous study, the imaging and analyses focused, among other issues, on assessing whether a curtain like the one found in the background of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring was originally present, and if color changes have occurred54. In the present study, a fragment of a paint sample taken from the area in the brownish-green background indicated in Fig. 5 was analyzed. D. Mahon et al. analyzed a cross-section of another fragment from the same location and found, over the ground preparation, two layers of an opaque green paint with a dark brownish-green glaze on top. These authors found that the opaque underpaint layers are composed mainly of a mixture of indigo, a copper-based green pigment – possibly verdigris, copper resinate or copper oleate –, and particles rich in aluminum, which might indicate the substrate of a yellow lake pigment. The thinner layer on top of the stratigraphy, corresponding to the glaze, was found to contain indigo, relatively small amounts of copper, and few particles containing aluminum which may also possibly indicate a yellow lake. These authors proposed that, based on its composition, it is likely that this glaze has discolored, and was originally a dark transparent green54. The sample analyzed by HPLC-qToF-MS comprised the two underpaint opaque green layers and the dark brownish-green glaze applied on top mentioned above.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, in memory of Theodore Rousseau Jr., 1979 (1979.396.1). Image is in the Public Domain. The red arrow shows the location of the sample analyzed in the present study, along the left edge of the painting, in an area of loss.

Extraction of the sample from this painting with HCl gave clear signals for isatin, luteolin, apigenin, chrysoeriol, and indigotin. This matched the reference for weld lake pigment and the composition observed for S2 from Mistress and Maid (Fig. 6). Because the sample analyzed from Study of a Young Woman was larger than those from Mistress and Maid, the intensities of the background peaks relative to the colorants are lower, giving a cleaner spectrum (Figs. 2 and 6).

Isatin (1), luteolin (2), apigenin (3), chrysoeriol (4), and indigotin (5) are identified.

In 1998, K. Groen et al. analyzed a sample from the background of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring using HPLC and reported the presence of weld, based on the detection of luteolin, mixed with a colorant derived from indigotin33. Although weld is the most common source of luteolin in Europe, many yellow colorants, including Daphne gnidium (spurge flax) and Genista tinctoria (dyer’s broom) also contain luteolin and related flavonoids as major components42. In 2018, re-analysis of the samples from Girl with a Pearl Earring, again with HPLC, confirmed the presence of luteolin as well as several additional components, including apigenin, a luteolin methyl ether (which the authors did not identify), and several flavonoid glycosides, supporting the earlier identification of weld34. Therefore, weld lakes appear to have been integral to Vermeer’s palette.

Although the use of yellow lakes derived from Reseda luteola is well documented and several studies of historic paints have confirmed its presence45,55, there have been few definitive identifications of them in paintings, particularly in comparison with the body of scientific evidence available about its use as a textile dye. In addition to the reports by K. Groen et al. and A. Vandivere et al., S. E. Jorge-Villar et al. used Raman spectroscopy to propose the use of weld in a Roman wall painting56, and K. Wustholz and co-workers identified the lake pigment in an eighteenth-century oil painting by R. Feke using SERS28,57.

HPLC-qToF-MS analysis of Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, Rembrandt van Rijn, 1653

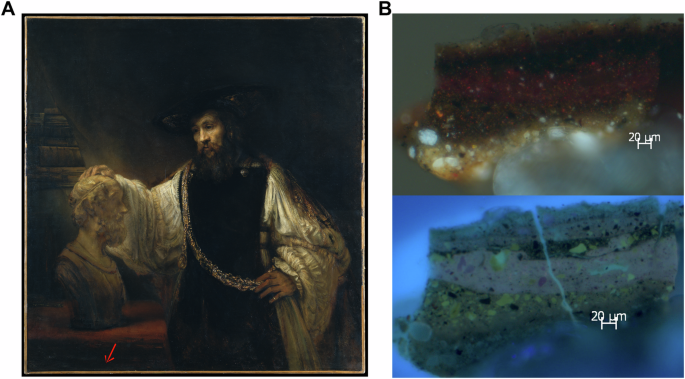

Rembrandt’s complex mixing and layering of opaque and lake pigments to achieve different effects in his paint passages – along with the use of smalt with low cobalt contents for translucency – has captivated researchers for decades5,58,59. In Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, Rembrandt’s masterful technique is evidenced in the mixing and layering in a sample cross-section taken from a shadow area in the tablecloth (Fig. 7A). In this cross-section, the red and yellow lake pigments are visible as pink and yellow particles, respectively, in the photomicrograph taken with UV illumination (Fig. 7B, bottom image); however, the identification of the yellow lake pigment’s source has been challenging5. Several attempts to identify the yellow lakes using HPLC did not give definitive results. In 1995, J. Kirby analyzed two unmounted samples from this painting (one from the tablecloth and one from the skirt of Aristotle’s apron) and suggested that the lake could be weld, though acknowledged that a Rhamnus species could not be eliminated as a source49. In 2014, N. Shibayama carried out HPLC analysis on a fragment of the sample taken from the location shown in Fig. 7A, identifying the red lake as cochineal, and analysis by SEM–EDS of the paint cross-section associated with this fragment (Fig. 7B) revealed presence of particles containing aluminum, most likely a component of a lake substrate50,60. The composition of the yellow lake remained a mystery5.

A Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, 1653, signed and dated ‘Rembrandt. f. 1653.’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 61.198. Purchase, special contributions and funds given or bequeathed by friends of the Museum, 1961. The red arrow indicates the location where the sample analyzed by HPLC-qToF-MS was taken. B Photomicrograph of a cross-section sample taken from the spot indicated in A, photographed with visible (top) and with UV illumination (bottom), original magnification 200x. The sample analyzed by HPLC-qToF-MS consisted of a fragment associated with this cross-section.

HPLC-qToF-MS analysis of another fragment of the sample taken from the location indicated in Fig. 7A, stored in The Met’s archives, performed during the present study confirmed the presence of both red and yellow lakes. Pigment samples were extracted using a boron trifluoride-methanol solution in a method adapted from the procedure developed by J. Kirby and R. White at the National Gallery, London32. This technique, the same used by Kirby for the 1995 analysis and Shibayama in 2014, was selected because transmethylation is effective at breaking up the polymerized medium of the paint while bringing the colorant into solution for chromatographic analysis. Furthermore, the samples were determined to be sufficiently large to benefit from a milder extraction technique.

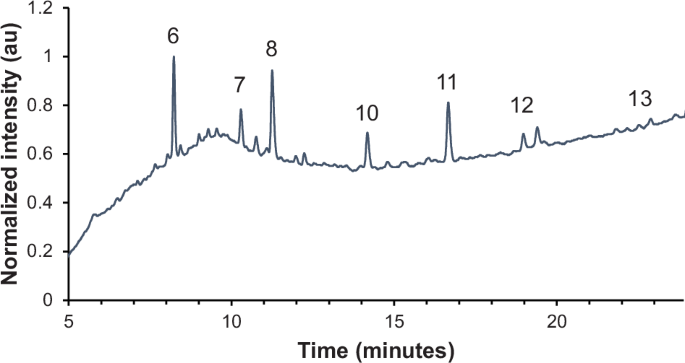

Several peaks related to cochineal and products of the boron trifluoride reaction were detected (Fig. 8 and Table 2). The major component was carminic acid at 8.2 min, with a methylated derivative of carminic acid eluting at 11.1 min. The retention times and MS/MS fragmentation of these components match those found in a reference of carmine nacarat in linseed oil following boron trifluoride extraction (Fig. 9A). Unlike in the reference, no minor components of cochineal – such as flavokermesic acid, kermesic acid, or various kermesic acid glycosides61 – were detected in the sample from the painting, possibly because of its size or age. These findings support the earlier HPLC results5.

Carminic acid (6), two side products related to reaction of carminic acid with BF3-MeOH (7, 8), kaempferol (10), rhamnetin (11), rhamnocitrin (12), and emodin (13) are identified.

UV-visible chromatograms (350 nm) for references of A carmine nacarat and B Rhamnus extracted with BF3–MeOH. Inset shows detailed view of colorants 10–13 Carminic acid (6) and two side products related to reaction ofcarminic acid with BF3–MeOH (7,8) are identified in 9A. Quercetin (9),kaempferol (10), rhamnetin (11), rhamnocitrin (12), and emodin (13) are identified in (B).

Carminic acid is the major component of several species of scale insects: Dactylopius coccus (Mexican cochineal), Porphyrophora polonica (Polish cochineal), and Porphyrophora hamelii (Armenian cochineal)42,62,63. Without being able to detect minor components of cochineal, we cannot differentiate among species. J. Kirby and R. White found that prior to the seventeenth century, Northern European painters relied more heavily on madder (and kermes, beginning in the sixteenth century) for reds, whereas Italian painters were more likely to use scale insects, such as kermes or Polish cochineal32. Beginning in the seventeenth century, cochineal from South and Central America began to spread across Europe. Therefore, the pigment used by Rembrandt may have been Mexican cochineal. Cochineal lake pigments were considered valuable due to their translucency and were used in glazes over other pigments. In addition to Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, Rembrandt’s use of cochineal in glazes to depict silk textiles has been observed in Alexander the Great and The Jewish Bride64.

Lake pigments derived from cochineal (and other scale insects) have been identified in works of art by HPLC32,51,65, Raman spectroscopy66, SERS31, and FORS26. Paints in two works by Rembrandt, Hendrickje Stoffes and Self Portrait, Aged 63, have been proposed to contain a mixture of cochineal lake pigments and an unidentified yellow lake48. Cochineal has also been detected in the jacket of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring67.

As for the yellow component in the sample from Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, several flavonoids were detected. Kaempferol, a flavanol, is present at 14.2 min, along with two other flavanol derivatives: rhamnetin (16.5 min) and rhamnocitrin (18.8 min). Trace emodin, an anthraquinone, was also detected (22.5 min). These components are present in Rhamnus species, such as those used to produce the colorants known as Persian berries or Avignon berries, sometimes referred to as stil de grain or “Dutch pink”42,68. Rhamnus is also often associated with the colorant known as schijtgeel or schietgeel (“shit yellow”) in seventeenth century Dutch sources, likely named for its brownish-yellow hue, although its similarity to the word verschietgeel (“disappearing yellow”) has led to some ambiguity59,69. The term is used both for the specific pigment made from unripe berries of Rhamnus species and as a more general term for light-sensitive yellow lakes, sometimes within the same publication, making interpretation of historical sources regarding its use somewhat challenging25,69,70,71.

Our identification of Rhamnus was confirmed by the analysis of a reference sample of Persian berries extracted with a boron trifluoride-methanol solution (Figs. 9B and 10). Quercetin, a major component observed in the reference material, was not detected in the paint sample. This difference could be related to the fact that the reference material for Persian berries is a dyed textile rather than a lake pigment, or due to the presence of a different Rhamnus species, which can vary in composition68. Alternatively, degradation of the pigment over time could also lead to compositional differences: photostability experiments have shown quercetin to be significantly less stable than luteolin due to the effect of the former’s 3-OH group41,72,73.

Major colorants present in a reference sample of Rhamnus extracted with BF3–MeOH.

The use of Rhamnus species for dyeing has been demonstrated in textiles74,75,76,77,78, but there are fewer examples of definitive identification of Rhamnus lakes in paintings. Colorants from Rhamnus species have been discovered on a wall cloth in the Palace Museum in Beijing79, as well as in Jean-Baptiste Oudry’s Tiger (1740) and Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893)80. Using photoluminescence spectroscopy (PLS), researchers proposed the presence of a Rhamnus species in three Dutch still life paintings (two by Coenraet Roepel and one by Willem Kalf) based on the similarity of the spectrum from the unknown lake with that of a reference of Rhamnus cathartica71. No spectra are presented in this publication for comparison, and due to the well-documented spectral similarity of flavonoid-based lakes (and the impact of both preparation and environment on the photophysical properties of lakes81,82), these results are difficult to confirm.

As for Rembrandt’s use of Rhamnus lakes, D.A. Peggie and J. Kirby have suggested that the yellow lake combined with madder and cochineal in Self Portrait, Aged 63 likely derives from a Rhamnus species, although they were not able to make a definitive identification using HPLC51,83. Our results by HPLC-qToF-MS confirm the use of Rhamnus in Aristotle, providing the first definitive identification of a yellow lake used by Rembrandt and the first unequivocal identification of molecular markers from a Rhamnus species in a 17th-century Dutch painting by chromatographic means. These results also give us a better understanding of the sophisticated technique that Rembrandt used to achieve complex shadows with rich depths in Aristotle with a Bust of Homer.

Technological advancements in recent decades, including high-resolution mass spectrometry, have enabled identification of yellow lake pigments in archived samples from works of art.

Vermeer mixed copper-based opaque green pigments with indigo, yellow lakes, and minor amounts of other opaque pigments to achieve dark translucent greens. These have now discolored to brownish greens and, therefore, lost their original appearance. HPLC-qToF-MS analysis of samples from Mistress and Maid and Study of a Young Woman allowed the identification of the yellow lake as made from Reseda luteola, or weld. These results, along with previous reports of weld33,34, contribute to our understanding of Vermeer’s materials and techniques, providing strong evidence of the importance of weld lake pigments in his palette, and allow a better understanding of the paints’ original appearance in these works.

In Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, Rembrandt mixed and layered red and yellow lakes with opaque pigments to achieve deep, rich shadows in a manner that attests to his mastery; however, the composition of the yellow lakes used by Rembrandt in his paintings has been a mystery. Liquid chromatography combined with the sensitivity of high-resolution mass analysis allows the identification of colorants at extremely low concentrations, which is critical for the characterization of yellow lake pigments. To the best of our knowledge, the identification of a Rhamnus species in Aristotle with a Bust of Homer provides the first conclusive identification of a yellow lake in a painting by Rembrandt, supporting previous analysis that had suggested his use of this lake. This may also be the first unequivocal identification of Rhamnus in a 17th century Dutch painting, despite being frequently discussed in the historical literature69. In Aristotle, to achieve the complex hue in the tablecloth shadow, he mixed and layered a Rhamnus lake with a red lake based in carminic acid. There is evidence to suggest that Rembrandt likely used this pigment in at least one other painting, but further studies are necessary to reveal if Rembrandt preferred this yellow lake pigment over others51,83.

There are many reasons why an artist might choose one pigment source over another. Although yellow lakes are notorious for their relative instability to light, particularly when compared with yellow mineral pigments, certain yellow lakes are more prone to fading than others. Saunders and Kirby compared the light stability of several red and yellow lakes in various forms. When comparing yellow lakes with the same substrate, weld pigments were found to be more stable than those made from buckthorn16; however, substrate and additives can also influence photostability significantly, making it challenging to draw conclusions based on the colorants alone. There is also some indication from experiments on dyed cellulose that luteolin forms a colored degradation product that changes the overall appearance of the dye72. If this degradation product also forms in a weld-based pigment, visible discoloration could occur.

The chemical similarity of the two pigment sources detected in this study, Reseda luteola and a Rhamnus species, highlights the need for sensitive and specific techniques. For example, the major compounds detected in both sets of samples (luteolin and kaempferol) are structural isomers that have the same chemical formula, C15H10O6, and differ only in the connection of a single OH group. However, not only does chromatography allow us to differentiate these two isomers based on retention time (12.8 vs. 14.2 min), but HPLC-qToF-MS provides additional structural information about each component in the form of UV-visible absorption spectra and MS/MS fragmentation (see Supplementary Information File 1)84,85,86.

The use of molecular information is particularly critical when references are not available for comparison. In the case of Reseda luteola and Rhamnus species, references of the colorant in the form of lakes and dyed material are relatively easy to access, either in museum reference collections or even from commercial sources. This availability enables researchers to study and compare mockups alongside “real” samples from works of art. With the increasing availability of high-resolution instrumentation such as HPLC-qToF-MS combined with an interest in applying scientific research to works from cultures and regions for which materials have not been as well documented or studied, researchers are often tasked with identifying unknown components for which references may not be readily available40,44,87,88,89,90,91.

The results of this research would not be possible without technological advancements nor without the patience of scientists, curators, and conservators that allowed for decades-old samples to be revisited and restudied. We hope that these results will encourage fellow researchers to revisit their own unanswered questions with a combination of new perspectives and advanced instrumentation.

Responses