Feedback effect of the size of mineral particles on the molecular mechanisms employed by Caballeronia mineralivorans PML1(12) to weather minerals

Introduction

Mineral weathering is a fundamental process with important impacts on humans (e.g., architectural patrimony conservation and human health (tooth decay)) and their environment (e.g., erosion, and soil fertility). Its action can be considered at different time scales. In the long term, it contributes to shaping landscapes and determining soil fertility and water quality. The release of nutrients from minerals and rocks strongly influences soil formation and ecosystem functioning. On a shorter time scale, it ensures the renewal of the soil nutrient content through the release of essential nutrients (e.g., P, K, Mg, and Fe)1. Mineral weathering is particularly important in nutrient-poor and low-input ecosystems, where it plays a pivotal role in the development of ecosystems. This is the case for forests in temperate regions, which grow primarily on nutrient-poor, acidic, and rocky soils. Under these conditions, the growth and health of trees rely on the important recycling of the nutrients contained in organic matter and access to the nutrients released from soil minerals through the mineral-weathering process.

A mosaic of different minerals and rocks is found in the soil. These rocks and minerals differ in their age, chemical content, and size. Among them, silicates constitute one of the most abundant mineral classes2. The dissolution rates of these minerals vary strongly between mineral types. This variation can be explained by differences in their crystalline structure, chemical composition, surface area, presence of cracks and holes on their surfaces and solution chemistry3. All these physicochemical properties determine the weatherability of minerals; thus, when they are placed under similar conditions (e.g., acidic conditions), some minerals are very resistant (e.g., quartz), whereas others are more easily weathered (e.g., olivine and pyroxene). Similarly, important differences in mineral weatherability can be observed for a given mineral depending on its surface area (i.e., particle size). Abiotic experiments and in situ observations revealed that smaller mineral particles weather faster than larger particles do4. This difference is explained by the higher surface area/volume ratio of the small particles, which makes them more reactive to their environmental conditions. In soils, small mineral particles (i.e., the fine earth fraction) represent an essential reservoir of nutritive elements of base cations, which are mobilizable through mineral weathering. Key questions include how the physicochemical properties of these minerals affect their interactions with microorganisms and how they modify the ability of the microorganisms to weather minerals as well as the given molecular mechanisms.

In addition to the action of abiotic weathering (i.e., water circulation and carbonic acid action), in situ, measurements have demonstrated that soil minerals are more intensively weathered in the vicinity of the root system (i.e., rhizosphere)5,6,7,8,9. This increase is linked to the chemical action of the plants and associated microorganisms (i.e., bacteria, fungi) that produce protons, organic/inorganic acids, and chelating compounds as well as the ability of bacteria and fungi to explore the soil, recover nutrients and colonize cracks and pores inaccessible to tree roots10,11. Notably, plants12,13 and microorganisms14,15 have been shown to accelerate mineral weathering independently or synergistically16,17,18. Effective mineral weathering bacteria have been observed in the rhizosphere of various plants (e.g., cactus and trees)19,20,21 and are particularly enriched in the rhizosphere of plants growing in nutrient-poor soils22,23. Mineral weathering bacteria have also been observed on the surface of minerals (i.e., the mineralosphere), with a relatively high frequency on poorly weatherable minerals24,25. In both cases, nutrient availability has been considered a key driver of MWe communities.

Mineral weathering bacteria are known to use acidolysis and chelation as the main molecular mechanisms to weather minerals and rocks, but the genetic basis, regulation, and interplay between mineral properties and bacteria remain to be determined26. Regarding the acidification-driven mineral weathering mechanism, the direct oxidation of glucose is considered an essential metabolic pathway27,28. It allows the periplasmic conversion of glucose into organic acids and protons that are then exported outside of the cell, leading to local acidification of the surrounding environment and dissolution of minerals. To date, two types of enzymes have been reported to participate in this metabolic pathway and in the dissolution of minerals: (i) the glucose dehydrogenase dependent on the pyrroloquinoline quinone cofactor (GDH-PQQ dependent29,30,31,32,33,34,35); and (ii) the glucose/methanol/choline oxidoreductase dependent on the flavin adenine dinucleotide cofactor (GMC FAD-dependent)36. In the case of the chelation-driven mineral weathering mechanism, different families of siderophores (i.e., non-ribosomal peptide synthetase-dependent (NRPS)37,38,39,40 and NRPS-independent (NIS)41) have been demonstrated to contribute to the dissolution of iron-containing minerals.

Different omics studies have revealed a complex response (i.e., differences in gene expression or protein production) of some bacterial strains to the presence of minerals35,42,43,44. Solution chemistry45 and the presence of some nutritive elements have also been shown to influence the MWe mechanisms employed by bacteria. In this context, the phosphorus concentration in solution has been shown to have an effect on the acidification-driven mineral weathering mechanism, with an absence of acidification and thus mineral dissolution, at high P concentrations and, conversely, high acidification and thus dissolution, at low P concentrations, but evidence remains limited46,47,48. Similarly, iron availability is known to regulate the production of siderophores. However, the influence of mineral physicochemical properties on the effectiveness of MWe bacteria and the mechanism in use (i.e., acidification or chelation-driven mineral weathering) are still not established. Deciphering the interplay between mineral properties, solution chemistry and the mechanisms employed by bacteria to mobilize nutrients from minerals and rocks has important impacts on different fields (i.e., soil sciences, geochemistry, mineralogy, material conservation, and environmental microbiology) and on our understanding of the role of microorganisms in soil nutrient mobilization and cycling. In this study, we considered that MWe activity may be the response of bacteria to nutrient deficiency and that the reactivity of minerals may be an important parameter affecting the MWe ability of bacteria. In this context, the aims of our study were to determine (i) the effect of the mineral size on the mineral weathering ability of the strain Caballeronia mineralivorans PML1(12), (ii) how this parameter affects the molecular mechanisms used by this strain to weather minerals (i.e., acidification or chelation-driven mineral weathering), and (iii) whether the action of each molecular mechanism changes over time. Biotic and abiotic microcosm experiments using different sizes of biotite particles incubated in the presence or absence of the effective mineral weathering bacterial strain Caballeronia mineralivorans PML1(12) and its mutants that were unable to acidify or chelate iron were conducted (see Fig. S1for the experimental design).

Results

Abiotic characterization of biotite weatherability: influence of particle size and weathering agents

The weatherability of the different biotite particle sizes considered in this study was assessed through abiotic weathering assays (i.e., with a solution of HCl at pH 3 to mimic acidification or with a solution of 5 mM citrate at pH 6.5 to mimic chelation). After 7 days of incubation, the amounts of Fe and Al in the solution were measured and used as indicators of biotite dissolution. Under our experimental conditions, significantly greater (P < 0.05) amounts of Fe and Al were measured when the biotite particles were incubated at pH 3 than when they were incubated with citrate, regardless of the particle size (Fig. 1; bars left axis). Notably, the smaller the particles were, the higher the level of dissolution was for both the HCl and the citrate treatments. The only exception was between the biotite size categories <20 µm and 20–50 µm, for which no significant difference in Fe or Al was observed (P < 0.05). A significant increase (P < 0.05) in the pH of the solution from 3 to 4 was observed when biotite particles <20 µm were incubated in the presence of HCl (Fig. 1; points on the right axis), whereas the pH of the solution remained stable when the biotite particles were incubated in the presence of citrate.

The impact of an acidic solution (HCl) and of a chelating solution (citrate) in the weathering of different sizes of biotite particles was determined by the concentration of Fe and Al released from the minerals after 7 days of culture. A Concentration of iron in solution after 7 days incubation at 25 °C with HCl at pH = 3 (bars in blue; left axis) and with a solution of citrate 5 mM (bars in violet; left axis). B Concentration of aluminum released in solution after 7 days incubation at 25 °C with HCl at pH = 3 (bars in blue; left axis) and with a solution of citrate 5 mM (bars in violet; left axis). Each value is the mean of three independent replicates ± the standard error of the mean. Measures with different letters are significantly different according to an ANOVA test (P < 0.05). The left axis corresponds to the bars and element concentration, while the right axis refers to the points and the measured pH in the solution of each sample.

Impact of the particle size on the mineral weathering effectiveness of strain PML1(12)

Strain PML1(12) and its mutants (unable to acidify or produce siderophores) were incubated with different sizes of biotite particles. The incubation was performed under low buffering conditions (i.e., BHm) to decipher the impact of acidification, and under high buffering conditions (i.e., ABm-Fe) to decipher the impact of siderophore production on mineral weathering. Owing to the different molecular mechanisms employed in each culture medium and the better growth of strain PML1(12) and its mutants in the ABm-Fe medium than in the BHm medium (Fig. S2), the two culture conditions (i.e., BHm vs. ABm-Fe) were analyzed independently. For each culture condition, a short incubation time (after 2 days in BHm medium and after 4 days in ABm-Fe medium) and a longer incubation time (after 7 days) were considered. At each time point, the quantity of different elements in the solution together with the physiological characteristics of the bacteria (i.e., growth, acidification and siderophore production) were measured.

Acidification-driven mineral weathering experiments

In BHm medium, significantly higher iron concentrations were measured in the presence of strain PML1(12) after 2 days for biotite particles smaller than 200 µm (6.32 ± 1.19 mg Fe L-1 with particles <20 µm; 5.13 ± 0.43 mg Fe L-1 with particles measuring 20–50 µm; and 0.67 ± 0.06 mg Fe L-1 with particles 100–200 µm) than in the presence of larger biotite particles (200–500 µm) or in the controls (values between 0.10 and 0.31 mg Fe L-1). Solution acidification was observed in the presence or absence of biotite (regardless of the particle size). Notably, an inverse relationship was observed between particle size and medium acidity. The treatments with larger biotite particles or the absence of biotite had greater acidity (pH = 3.2 ± 0.1 in the absence of biotite particles; pH = 3.3 ± 0.1 with particles between 100 and 200; pH = 3.4 ± 0.1 with particles between 200 and 500; pH = 4.0 ± 0.1 with particles between 20 and 50 µm; and pH = 4.3 ± 0.21 with particles <20). No acidification was observed for the gmc3::Tet mutant strain or the abiotic controls.

After 7 days, significantly higher concentrations of Fe (P < 0.05) were measured when strain PML1(12) was incubated with biotite particles ranging from 100 to 500 µm than with smaller particles or in the control treatments (Fig. 2A, bars left axis). These results are the opposite of those obtained after 2 days, suggesting that the dynamic effect is dependent on the particle size. After 7 days of incubation with biotite particles of 100–200 µm and 200–500 µm, the concentrations of iron in solution were 2.17 ± 0.02 and 1.72 ± 0.02 mg Fe L-1, respectively. In contrast, only concentrations between 0.2 and 0.4 mg Fe L-1 were measured in the supernatants of the WT strain in the presence of biotite particles <100 µm or with the mutant gmc3::Tet and in the non-inoculated treatment. The Al concentrations measured in the solution followed the same trend as those of Fe (Fig. 2B, bars left axis). For the incubation in the presence of biotite particles <100 µm (Fig. 2, points on the right axis), the pH of the solution increased from 3.2 (after 2 days) to 6.2 (after 7 days). In contrast, the solution remained acidic when the WT strain was incubated in the absence (pH = 3.9 ± 0.1) or presence of biotite particles >100 µm (pH = 4.2 ± 0.1 for 100‒200 µm, pH = 4.3 ± 0.1 for 200‒500 µm).

The impact of the acidification-driven mechanism used by strain PML1(12) to weather biotite particles of different sizes was determined after 7 days of culture in liquid BHm. Biotite dissolution was estimated through the concentration of Fe and Al released in the solution. Each value is the mean of three independent replicates ± the standard error of the mean. Measures with different letters are significantly different according to an ANOVA test (P < 0.05). WT strain samples are shown in dark blue, gmc3::Tet strain samples in light blue and samples without bacteria in gray. Bars indicate Fe (A) and Al (B) concentration on the left axis, while yellow dots represent the mean pH of triplicate samples on the right axis.

Chelation-driven mineral weathering experiments

In the ABm-Fe medium, the measurements performed after 4 days revealed significantly higher (P < 0.05) concentrations of Fe when strain PML1(12) was incubated with biotite particles <200 µm (0.43 ± 0.02 mg Fe L-1 with particles between 50 and 100 µm; 0.39 ± 0.05 mg Fe L-1 with particles between 20 and 50 µm; 0.35 ± 0.02 mg Fe L-1 with particles <20 µm; and 0.16 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 with particles between 100 and 200 µm) than in the mutant or the non-inoculated conditions (values ranging from 0.01 and 0.09 mg Fe L-1). Notably, almost no siderophore activity was detected when the WT bacteria were incubated in the presence of biotite particles <20 µm (O.D.655nm = 0.34 ± 0.01) and were very low or low, in the presence of biotite particles at concentrations of 20–50 µm (O.D.655nm = 0.28 ± 0.01) and 50–100 µm (O.D.655nm = 0.23 ± 0.01), respectively. In contrast, high siderophore activity was detected when the WT strain was incubated with biotite particles >100 µm or in the absence of minerals (overall value of O.D. 655nm = 0.15 ± 0.02). No siderophore activity was detected for the rhiE::Gm mutant or in the abiotic cultures (overall values O.D. 655nm = 0.41 ± 0.02).

After 7 days, the Fe concentration in the solution confirmed that strain PML1(12) was effective at weathering biotite regardless of size (Fig. 3, bars left axis). Indeed, significantly greater (P < 0.05) amounts of Fe were detected under all the conditions in which the samples were inoculated with the WT strain (values between 0.42 and 1.14 mg Fe L–1) compared to the rhiE::Gm mutant, the abiotic control, the non-inoculated condition or the absence of biotite (values ranging from 0.18 and 0.21 mg Fe L-1). A detailed analysis revealed that the amount of iron in solution was significantly greater (P < 0.05) in the presence of biotite <100 µm particles (from 0.97 ± 0.06 mg Fe L-1 for <20 µm particles to 1.14 ± 0.22 mg Fe L-1 for 50–100 µm particles) than in the presence of larger particles ranging from 100 to 500 µm (0.59 ± 0.11 mg Fe L-1 for 100–200 µm and 0.42 ± 0.08 mg Fe L-1 for 200–500 µm). Aluminum was not considered an indicator of biotite solubilization under these experimental conditions (i.e., ABm-Fe), since the pH of the medium is stabilized by the buffer at 6.5, and Al precipitation is known to occur at nearly neutral pH. For manganese (Mn), which is a minor component of biotite, significant differences between the WT and the controls were also observed (Table S1). This chemical element, which was absent from the medium composition, followed a similar pattern to that of the Fe concentration. A significantly greater (P < 0.05) concentration of Mn was detected only in the presence of biotite particles <50 µm for the WT strain compared to the mutants and the non-inoculated condition. Notably, siderophore activity was confirmed only when the WT strain was incubated in the absence of biotite (O.D.655nm = 0.14 ± 0.01) or in the presence of biotite particles >100 µm (O.D.655nm = 0.14 ± 0.01 for 100–200 µm; O.D.655nm = 0.18 ± 0.01 for 200–500 µm) (Fig. 3, points on the right axis). Very low siderophore activity or no activity was detected with smaller biotite particles. The absence of siderophore activity was confirmed in the controls.

The impact of the chelation-driven mechanism used by strain PML1(12) to weather biotite particles of different sizes was determined after 7 days of culture in liquid ABm-Fe. Biotite dissolution was estimated through the concentration of Fe released in the solution. Samples corresponding to the WT strain are colored in dark violet, the mutant strain rhiE::Gm is colored in light violet and finally, samples colored in gray correspond to negative controls. Bars indicate Fe concentration on the left axis, while black dots represent the mean of Chrome Azurol S (CAS) test values on the right axis. A decrease of the absorbance (O.D. 655 nm) in the CAS test indicates the production of siderophore. In this study, siderophore is produced when values of absorbance are lower than 0.35. Each value is the mean of three independent replicates ± the standard error of the mean. Measures with different letters are significantly different according to an ANOVA test (P < 0.05).

Kinetic analysis of biotite weathering and the molecular mechanisms employed by strain PML1(12)

Since no acidification and low or no siderophore production was observed after 7 days of incubation of the WT strain with smaller biotite particles (i.e., <100 µm), kinetic analysis was employed to decipher the sequence of events allowing for the release of elements from biotite. This kinetic experiment was performed only in the presence of small particles of biotite (i.e., <20 µm, 20–50 µm, and 50–100 µm) for 96 h in both BHm and ABm-Fe media. Every 8 h, the quantity of different elements in the solution together with the physiological characteristics of the bacteria (i.e., growth, acidification and siderophore production) were measured. In addition, the glucose and gluconic acid concentrations were monitored in the BHm medium.

Kinetic analysis of the acidification-driven MWe mechanism

Under BHm conditions, our analyses revealed a progressive and significant increase in the amount of Fe (Fig. 4A) and Al (Fig. 4B) in the solution during incubation in the presence of biotite particles compared with the non-inoculated conditions or in the absence of the mineral. The amount of Fe rapidly increased to a maximum after 48–64 h of culture time, ranging from 4.24 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 for the particles <20 µm (after 56 h), 5.27 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 for the 20–50 µm particles (after 48 h) to 4.92 ± 0.02 mg Fe L-1 for the 50–100 µm particles (after 64 h). After this period, a progressive decrease to the minimal amount of iron was observed after 96 h of incubation, ranging from (i) 4.24 ± 0.01 to 2.48 ± 0.02 mg Fe L-1 for the particles <20 µm, (ii) 5.27 ± 0.01 to 2.16 ± 0.03 mg Fe L-1 for the 20–50 µm particles and (iii) 4.92 ± 0.02 to 3.61 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 for the 50–100 µm particles. Notably, the amount of iron quantified in the absence of the mineral (0.27 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 at 16 h and 0.31 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 at 96 h) or under abiotic conditions (0.18 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 at 16 h and 0.22 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 at 96 h) remained stable. The aluminum concentration increased over time, and higher values were obtained at the end of the analysis (88 h): 2.65, 2.23, and 3.2 mg of Al L-1 were obtained when strain PML1(12) was incubated in the presence of biotite particles <20 µm, between 20 and 50 µm and between 50 and 100 µm, respectively. The Al concentrations in the absence of biotite or in the abiotic control remained stable (approximately 0.1 mg/L). A significant decrease in pH was observed for all the cultures, regardless of particle size, compared with the non-inoculated treatment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4C). After 16 h, the pH of the solutions ranged from 3.73 ± 0.1 when PML1(12) was incubated in the absence of the mineral to 4.4, 4.1, and 4.0 ± 0.1 when incubated with particles measuring <20 µm, 20–50 µm, and 50–100 µm. The kinetic analyses revealed a progressive increase in the solution pH after 48 h, which differed according to the particle size. The smaller the particles are, the faster the pH increases. After 96 h, the pH increased in the presence of strain PML1(12) to 5.44 ± 0.1 with <20 µm particles and to 4.95 ± 0.1 with 20–50 µm particles, whereas it remained acidic at 50–100 µm (pH = 3.48 ± 0.1) or in the absence of biotite particles (pH = 3.23 ± 0.1).

Strain PML1(12) was incubated for 96 h in BHm or in ABm in the presence of biotite particles <20 (•), between 20 and 50 (▪) and between 50 and 100 (♦). The supernatant of these cultures was used to evaluate the changes along incubation in: (i) the solution chemistry (iron and aluminum concentration in mg L-1), (ii) acidification of the solution medium or (iii) siderophore production. Controls without biotite (▲) and without bacteria (▼) were included. One tube was sacrificed at each time point (each 8 h). Panels in blue corresponds to weathering through acidolysis (cultures performed in BHm; A, B, C) while panels in violet correspond to weathering through chelation (cultures performed in ABm; D, E). Each value is the mean of three technical replicates ± the standard error of the mean. A Evolution of iron concentration in BHm medium. B Evolution of aluminum concentration in BHm medium. C Evolution of pH in BHm medium. D Evolution of iron concentration in ABm medium. E Evolution of Chrome Azurol S (CAS) test values in the ABm medium.

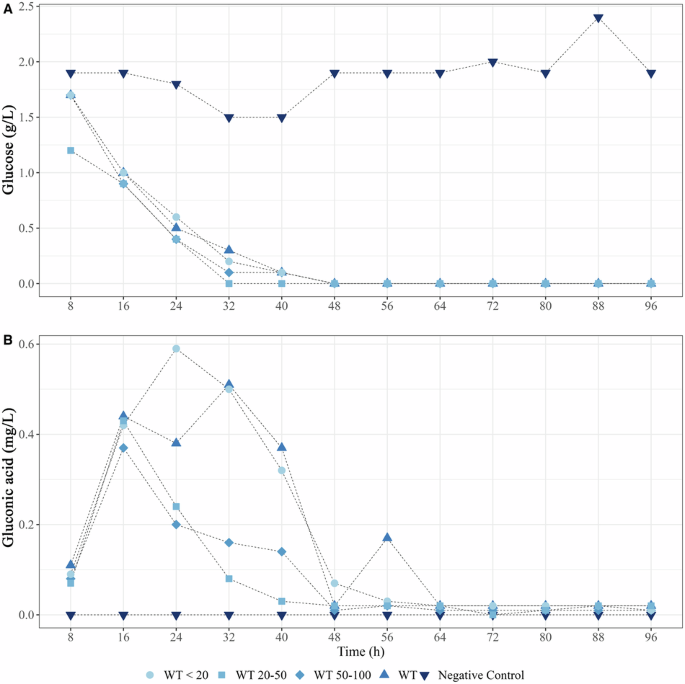

Because acidification depends on glucose and its transformation into protons and gluconic acid, the glucose concentration was measured in the culture supernatant (Fig. 5A). Our analyses revealed that strain PML1(12) consumed all the glucose (2 g L-1) after 40 h of culture under all conditions, whereas it remained relatively high (ca. 1.5 g L-1) in the abiotic control. Gluconic acid production began in strain PML1(12) after 8 h, and it reached its peak concentration between 16 and 32 h before disappearing completely (Fig. 5B). The maximum concentration of gluconic acid (ranging from 370 to 590 mg L-1) was measured between 16 h and 32 h, with a maximum after 24 h in the presence of biotite particles <20 µm.

A Glucose (g L-1) consumption; B gluconic acid production (mg L-1) measured during the incubation of strain PML1(12) in BHm with biotite particles <20 (•), between 20 and 50 (▪) and between 50 and 100 (♦). Controls without biotite (▲) and without bacteria (▼) were included.

Kinetic analysis of the chelation-driven MWe mechanism

Under ABm-Fe conditions, our analyses highlighted a gradual increase in the amount of Fe (Fig. 4D) in the solution up to a specific time point, after which it slightly stabilized. Differences were observed according to the particle size under consideration. The maximum Fe concentrations were measured at 88 h: (i) 0.79 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 in the presence of 50–100 µm biotite particles; (ii) 0.63 ± 0.01 mg Fe L-1 in the presence of 20–50 µm particles; and (iii) 0.55 ± 0.04 mg Fe L-1 in the presence of particles <20 µm. Siderophore activity began to be detectable after 16 h (Fig. 4E), and the O.D.655nm fluctuated during the incubation period from 0.18 ± 0.01 to 0.25 ± 0.02 in the presence or absence of biotite. The maximum siderophore activity was observed in the absence of biotite particles and after 24 h of incubation. Indeed, the O.D.655nm decreased to 0.06 ± 0.01, and this value remained stable throughout the 96 h of incubation (O.D.655nm = 0.08 ± 0.01). Notably, in the presence of biotite particles, the siderophore activity (i.e., O.D.655nm) remained high but never reached its maximum. The lower siderophore activity was measured after 96 h in the presence of all the particle sizes considered here (<20 µm; 20–50 µm; 50–100). Under the same conditions, no activity was detected for the mutant strain rhiE::Gm or for the abiotic control.

Inhibition of siderophore production by elements released from biotite

The production of chelating molecules has been largely demonstrated to depend on the Fe concentration in the medium, and indeed, this was also the case for the regulation of the siderophore rhizobactin by strain PML1(12). For strain PML1(12), rhizobactin production is known to be stopped at Fe concentrations above 0.7 mg Fe L-1 41. Since siderophores can chelate elements other than Fe, the inhibition of siderophore production by independently increasing the concentration of Mg or Al (until a maximum of 3 mg L-1) was tested. Neither Mg nor Al halted the biosynthesis of the siderophore (Fig. S3). Because these elements may influence siderophore production when mixed in solution with Fe, a solution derived from the abiotic dissolution of biotite (i.e., ADS) was used as a culture medium for strain PML1(12). The ICP analyses confirmed that the abiotic attack released Fe, Al, and Mg in solution, and the different incubation times provided different concentrations of each element in the different ADSs (the Fe concentrations in ADS1 = 0.47 mg L-1; ADS2 = 0.55 mg L-1, ADS3 = 0.65 mg L–1, ADS4 = 0.71 mg L-1 and ADS5 = 0.97 mg L-1; Table 1). After 3 days of culture of the WT strain and its rhiE::Gm mutant using these solutions as media, siderophore production was detectable for the WT strain cultivated in the ADS1 and ADS2 solutions, that were initially characterized by low Fe (siderophore activity: O.D.655nm = 0.20 ± 0.02 and 0.26 ± 0.02 for ADS1 and ADS2, respectively), but not in the ADS3 (0.65 mg Fe L-1), ADS4 (0.71 mg Fe L-1) and ADS5 (0.97 mg Fe L-1) solutions (mean O.D.655nm = 0.47 ± 0.03) (Fig. 6).

Strain PML1(12) (dark violet) and the mutant strain rhiE::Gm (light violet) were incubated in ABm-Fe amended with the elements released from biotite after abiotic dissolution (i.e., ADS solutions, ADS1, 2,3, and 4. These solutions have increasing concentrations of elements coming from biotite weathering; see “Methods” section). A control without bacteria (in gray) was also included. Siderophore production in ABm supplemented with the different concentrations of weathered biotite was assessed using the Chrome Azurol S (CAS) test. Siderophore activity is indicated by the yellow area in the figure. Each value is the mean of three independent replicates ± the standard error of the mean. Measures with different letters are significantly different according to an ANOVA test (P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we considered the model bacterial strain Caballeronia mineralivorans PML1(12) because of its effectiveness at weathering minerals and its ability to use acidification- and chelation-driven mineral weathering mechanisms49,50. According to the literature and the results of this study, acidification-driven dissolution occurs when bacteria have access to appropriate carbon sources (e.g., glucose) and under low-nutrient conditions, whereas chelation-driven dissolution can occur only when bacteria are growing under iron-deprived conditions. This relative separation of the two mechanisms is explained as follows: (i) acidification-driven metabolism allows for the release of iron (for iron-containing minerals/rocks) in the solution, which may inhibit siderophore production; (ii) acidification-driven metabolism is usually associated with a specific metabolic pathway (i.e., direct oxidative pathway), in which most of the carbon source is dedicated to acidification; and (iii) chelation-driven dissolution requires a low concentration of iron and high availability of other nutrients, as producing siderophores is an important cost for the cells. These are examples of how environmental conditions allow for physiological and functional adjustments in bacteria. Because bacteria interact with a broad range of mineral particle sizes across a soil profile, it can be expected that the mineral reactivity conditions the bacterial activity. This parameter has rarely been considered when the ability of bacteria to weather a material was tested. In this context, we designed an experimental setup to investigate the potential impact and feedback effects of the same mineral varying in particle size on the MWe mechanisms employed by strain PML1(12), their effectiveness, and their dynamics.

Acidification-driven mineral dissolution by bacteria is based on the massive conversion of glucose to gluconic acid and protons51,52,53,54. Glucose, which is readily degradable, is rapidly metabolized and has been demonstrated to confer a higher effectiveness at weathering than other carbohydrates for a wide range of bacteria [17, 49, 51–54, this study]. This metabolic conversion depends on a specific metabolic pathway, the direct oxidative (DO) pathway, and specific enzymes (i.e., PQQ-dependent GDH and FAD-dependent GMC oxidoreductase)29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Under our experimental conditions, we showed that glucose consumption is coupled with gluconic acid production and consumption, confirming previous observations50. Interestingly, no residual glucose was detected in the culture media after 48 h of incubation, regardless of the particle size. The pH reduction was evident as early as 16 h after inoculation. During this time period, the Fe and Al concentrations increased in the solution. This increase was greater for particles <100 µm with a maximum Fe concentration ranging from 5 to 6 mg Fe L-1 than for particles >100 µm, for which the Fe concentration was less than 1 mg Fe L-1. These first analyses clearly revealed a good relationship between the data obtained through abiotic dissolution experiments and those obtained early in the weathering assay with strain PML1(12), confirming that smaller particles are more reactive than larger particles are55,56,57. However, after this initial period and once glucose has been completely consumed, two different dynamics have been observed in the presence of strain PML1(12), which depend on the biotite particle size. For the biotite particles >100 µm (i.e., large particles), a continual increase in the Fe concentration in the solution was observed until maximum values of 1.7 and 2.2 mg Fe L-1. In this case, the pH remained acidic after 7 days of culture. In contrast, completely different dynamics were observed for biotite particles <100 µm, for which the pH reached neutral values and Fe was not detectable after 7 days of culture. This difference may be explained by the buffering capacity of biotite, which corresponds to the consumption of protons from the solution by the mineral surfaces during the dissolution process58,59. In our study, the dissolution of the smaller biotite particles (i.e., <100 µm) consumed larger quantities of protons, resulting in the progressive neutralization of the solution. This increase in the solution pH to near neutrality favors the precipitation of Fe and Al, a phenomenon already demonstrated in other mineral-weathering experiments51,60.

In the absence of acidification-driven MWe mechanisms, siderophores represent an alternative mechanism used by soil microorganisms to mobilize nutrients from minerals. Generally, siderophores are synthesized by bacteria under low concentrations of available iron, and threshold repression is observed between 0.1 and 1 mg/L Fe, depending on the bacterial strain41,61. While the affinity of siderophores for iron and the regulation of their synthesis are well established, our understanding of their interplay with iron-containing minerals and how their production is regulated in a biotic context remains limited. In our study, the use of a buffered medium (i.e., ABm) neutralized acidification-driven mineral dissolution, and a comparison of the WT strain PML1(12) and its mutant (which was unable to produce rhizobactin) revealed the role of siderophore production in the MWe process. Under ABm-Fe conditions, the siderophore rhizobactin significantly contributed to the dissolution of biotite, but with differences according to particle size. Notably, after 7 days of incubation, greater dissolution (based on the Fe concentration) was observed for the smaller particles (i.e., <100 µm) than for the larger particles (i.e., >100 µm) in the presence of the WT strain PML1(12) but not its mutant, highlighting the key role of siderophore production. However, at this incubation time (i.e., 7 days), no siderophore activity was detected during incubation with biotite particles <100 µm, whereas it was detected for larger particles or in the absence of biotite. The kinetic experiments we conducted with biotite particles <100 µm allowed us to understand what was happening more clearly. Our analyses revealed the early production of siderophores, which gradually decreased over time, whereas the concentration of Fe in the solution increased. These results revealed that the strain PML1(12) adjusts the production of its siderophore according to the degree of biotite dissolution. The results of the solution analyses performed after the weathering assays revealed that the Fe concentration was above 0.7 mg L-1 when strain PML1(12) was incubated with biotite particles <100 µm and lower than 0.7 mg L-1 for biotite particles >100 µm. Previously, some studies have shown the regulation of siderophore biosynthesis during the dissolution of different minerals. Ferret et al. 61 reported that a concentration of solubilized Fe from smectite as low as 0.1 mg/L was enough to repress pyoverdine production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. A similar phenomenon was observed for Pseudomonas aeruginosa62, for which a decrease in pyoverdine production was correlated with the level of asbestos dissolution and the quantity of Fe released into the solution. In our study, we considered an additional regulatory mechanism for the production of siderophores by strain PML1(12) based on the chemical elements (Al, Mg, and K) released jointly with Fe during biotite dissolution. Indeed, these elements may independently or synergistically regulate the production of siderophores or permit better growth and consequently greater production of siderophores, given that some siderophores have been shown to be able to chelate elements (i.e., Al, Mg) other than Fe63. However, when strain PML1(12) was incubated in solutions resulting from abiotic dissolution of biotite or in solutions containing high concentrations of specific elements (Mg, Al), no relationship was observed between the siderophore activity and the nutrient concentrations measured here (i.e., Mg, Al). The single exception was with Fe. Notably, with the ADS, the Fe concentration varied from 0.47 to 0.97 mg L-1, but siderophore activity was detected only at 0.65 mg Fe L-1.

The data accumulated in this study highlight that, regardless of the mechanisms used by strain PML1(12) to weather minerals (i.e., acidification of the environment and siderophore production), particle size affects its ability to solubilize biotite. Importantly, our experimental design revealed that mineral bioalteration by bacteria cannot be fully predicted on the basis of abiotic experiments only (i.e., siderophores and organic acids) because particle size promotes metabolic and physiological adjustments and feedback effects over time. A dynamic model is proposed here based on the initial availability of glucose. During the initial stages of the interaction (less than 72 h), owing to their reactivity and the action of the strain PML1(12), smaller particles (i.e., <100 µm) are characterized by a rapid release of nutritive elements in the solution. Under these conditions, rapid repression of siderophore biosynthesis occurs. In the long term, the progressive neutralization of the medium, due to proton consumption by the mineral surfaces, allows for the (re)precipitation of elements (i.e., Fe and Al). This precipitation may lead to a final reduction in Fe availability in solution and to a new phase of siderophore production activation if carbon metabolism supports this production. In contrast, larger particles (i.e., those >100 µm) are characterized by the gradual release of nutrients and the maintenance of an acidic pH (linked to the DO pathway) under non-buffered conditions or the continual production of siderophores under buffered conditions. As long as carbon metabolism supports acidification-driven dissolution (i.e., low nutrient availability and the presence of glucose or glucose polymers) or chelation-driven dissolution (i.e., low iron availability and the presence of a ‘good’ substrate), the process can continue. Together, the findings in this work underline the importance of the size of the mineral particles that play a key role in regulating and/or neutralizing bacterial metabolism. This parameter, which affects the reactivity and weatherability of minerals, cannot be considered independent of the chemistry of the solution. These new findings have important implications not only for our understanding of the role of microorganisms in bioalteration, nutrient cycling, and soil fertility in material conservation but also for the development of fertilization processes based on natural products.

Methods

Bacterial strains

In this study, the model strain Caballeronia mineralivorans PML1(12) and two related mutants that were impaired in their ability to weather minerals were used to elucidate the impact of mineral properties on the weathering effectiveness of the WT strain. Strain PML1(12) was isolated from the ectomycorrhizosphere of Scleroderma citrinum-oak growing on nutrient-poor acidic soil. This bacterial strain was demonstrated to be effective at weathering minerals through acidification- and chelation-related MWe mechanisms. Its ability to acidify its surrounding environment is based on the high production of protons and gluconic acid when glucose is metabolized50, whereas its ability to chelate iron is based on the production of the siderophore rhizobactin41. For both mechanisms, mutants have been obtained to test the potential link between each molecular mechanism, the solution chemistry, and the mineral properties. Siderophore biosynthesis is known to depend on the rhi region in strain PML1(12)41. A rhiE::Gm mutant strain was previously constructed and demonstrated to be unable to produce siderophores and was thus also unable to weather minerals through chelation. For acidification, a Tn5 mutant unable to acidify the medium was obtained using the plasposon Tn5-OT182, as described previously64,65,66. The localization of the plasposon in the genome of strain PML1(12) allowed us to localize its insertion in a gene encoding a cytochrome subunit of a GMC oxidoreductase67. This gene is associated with a small and a large subunit related to the GMC3 oxidoreductase described in Uroz et al. 50. This mutant, which was identified as gmc3::Tet in this study, is unable to weather minerals through acidolysis, as stated for TriCalcium Phosphate (TCP). The TCP composition is as follows (in g L-1): NH4Cl, 5; NaCl, 1; MgSO4, 1; Ca3(PO4)2, 4; glucose, 10; and agar, 15; and adjusted to pH = 6.568. For routine experiments, all the strains were cultivated in an ABm medium. The ABm composition (g L-1) is as follows: NH4Cl, 1; MgSO4, 7·H2O, 0.3; KCl, 0.15; CalCl2, 2·H2O, 0.0033; KH2PO4, 3; Na2PO4, 2·H2O, 1.15; and Fe, 0.025; and it was adjusted to pH 7. Antibiotics were added to the media only for inoculum production at the following final concentrations: tetracycline 10 μg mL-1 or gentamycin 20 μg mL-1.

Culture media

The choice of the media used in this study is justified by the different mechanisms (i.e., acidolysis and chelation) employed by our model bacterial strain to weather minerals and observations from previous studies48,69,70,71. In this context, two culture media were used. To investigate bacterial weathering through acidification, a modified version of Bushnell-Haas medium (BHm) was used49. This medium is devoid of iron and has a low buffering capacity. These conditions correspond relatively well to the nutrient-poor conditions occurring in sandy soils on which forests are developed. Glucose (2 g/L final concentration) was used as the sole carbon source. The BHm composition was as follows (g L-1): KCl, 0.020; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.150; NaH2PO4·2H2O, 0.080; Na2HPO4·2H2O, 0.090; (NH4)2SO4, 0.065; KNO3, 0.100; and CaCl2·2H2O, 0.020; adjusted to pH 6.549. To investigate bacterial weathering through chelation, a modified version of the ABm medium was used. This medium is derived from the ABm medium described above but is characterized by the absence of iron (ABm-Fe) and a strong buffering capacity (compared with the BHm medium). The strong buffering capacity of this medium limits the passive dissolution of minerals and consumes all the putative protons produced by strain PML1(12), allowing us to focus only on the chelation mechanism. In this case, mannitol (2 g L-1 final concentration) was used as the carbon source. These conditions correspond relatively well to calcareous soils on which forests are developed.

Preparation of bacterial inoculum

For each of the assays presented in this work, the wild-type (WT) and the two mutant strains (gmc3::Tet, impacted by the acidification-driven weathering mechanism, and rhiE::Gm, impacted by the chelation-driven weathering mechanism) were recovered from glycerol stock (−80 °C) and grown on plates of solid ABm medium (25 °C) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. After 3 days of culture, one colony of each strain was selected and inoculated in 10 mL of liquid ABm medium (supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic for the mutants). The liquid cultures were incubated at 25 °C under 150 rpm agitation. After 3 days, the cultures were centrifuged at 9000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the pellet was washed three times with sterile Milli-Q water. The pellets were ultimately resuspended in sterile Milli-Q water, and the optical density (O.D. 595nm) was adjusted to 0.9 ± 0.03, corresponding to 2 × 109 cfu mL-1.

Biotite characteristics

Biotite was selected for this study because it represents a phyllosilicate frequently found in acidic forest soils. In our study, we considered a batch of biotite samples collected in Bancroft (Canada). Biotite contains different essential nutritive elements for trees, such as K, Mg, or Fe. The chemical composition of the biotite used here was 41.01% SiO2, 10.9% Al2O3, 2.21% Fe2O3, 10.05% FeO, 0.27% MnO, 18.9% MgO, 0.41% Na2O, 9.46% K2O, 2.28% TiO2, 4.42% F, and 0.08% Zn. Its structural formula is (Si3Al1) (Fe3+0.12 Fe2+0.61 Mg2.06 Mn0.02 Ti0.13) and K0.88 Na0.06 O10 (OH0.98 F1.02)72. To prepare the biotite particles, the purest crystals were first manually selected. Biotite crystals were fragmented and inspected with a stereomicroscope to exclude impurities (i.e., calcite, quartz, and iron oxides). Then, they were ground and subjected to ultrasonication (2 min, three times at 100 V) to remove the fine particles that electrostatically adhered to the particles. The ground biotite was then washed three times with distilled water and sieved through different mesh sizes to separate the different particle sizes. Five ground biotite particle sizes were selected for this study: (i) smaller than 20 µm; (ii) 20–50 µm; (iii) 50–100 µm; (iv) 100–200 µm; and (v) 200–500 µm.

Biotite abiotic weathering assays

To avoid contamination from the glass tubes, all the sample containers were rinsed once with 3.6% HCl and then three times with Milli-Q water. Then, the HCl-rinsed tubes were filled with 100 mg of biotite particles of the given sizes (i.e., <20 µm, 20–50 µm, 50–100 µm, 100–200 µm and 200–500 µm) and autoclaved at 121 °C. Tubes without minerals were used as controls. Following tube autoclaving, 5 mL of sterile water solution containing HCl at pH 3 or 5 mM citrate solution was added to the tubes to mimic abiotic weathering through acidolysis or complexolysis, respectively. The tubes were incubated at 25 °C for 7 days at 150 rpm. After 7 days of incubation, the concentrations of Fe, Al, Mg, Mn, and Si and the pH were determined after the centrifugation (9000 × g for 15 min) and filtration (0.22 µm; GHP Acrodisc 25 mm syringe filter; PALL) of the solutions. The concentrations of various elements (i.e., Fe, Al, Mg, Mn, and Si) in the solution were quantified by ICP‒AES. For all the ICP analyses presented in the manuscript, the solutions (culture supernatants and controls) were diluted 1/3 to fit with the standard concentrations used here (i.e., 0.005–10 mg L-1), and the final concentrations were obtained by using a correction factor (3×). These elements were selected because they are present in biotite. The pH was determined using the bromocresol green method49. In brief, 180 µL of the filtered solution was mixed with 20 µL of bromocresol. The optical density (O.D.595nm) was measured to determine the pH according to a calibration curve.

Biotite biotic weathering assays

The same procedure described above for the cleaning and preparation of glass tubes was performed. Then, 4.5 mL of BHm medium (for the acidification-driven mineral weathering assay) or 4.5 mL of ABm-Fe medium (for the siderophore driven mineral weathering assay) was added to the tubes containing or not containing the mineral particles before they were autoclaved at 121 °C (Fig. S1). Finally, 0.5 mL of bacterial inoculum was added to the tubes. Non-inoculated media with biotite and inoculated media without biotite were used as abiotic and biotic controls of weathering, respectively. All the treatments were performed in triplicate. The samples were incubated under agitation at 150 rpm and 25 °C. After 2 days of incubation in the case of BHm, 4 days in the case of ABm-Fe, and 7 days for both media, the cultures were used to determine (i) bacterial growth; (ii) concentrations of Fe, Al, Mg, Mn and Si in solution; (iii) pH; and (iv) siderophore production. Days two (for BHm) and four (for ABm-Fe) were chosen as time points, because they align with the optimal time periods for each mechanism. Additionally, measurements were performed at 7 days to observe the responses after longer incubation times. Bacterial growth in the liquid culture was measured directly by measuring the optical density at 595 nm (O.D. 595nm) (Bio-Rad, model iMark) in 200 µL after the sedimentation of the biotite particles. On days 2 and 4, iron concentration was measured in solution using the ferrospectral method. Iron is a good indicator of the global dissolution of biotite. For this purpose, 20 µL of a ferrospectral solution was mixed with 180 µL of the culture supernatant (filtered at 0.22 µm). Then, the O.D.595nm was measured, and the iron concentration was calculated according to a calibration curve49. After 7 days, the concentrations of Fe, Al, Mg, Mn, and Si in solution were measured by ICP‒AES. Measurements were performed after centrifugation at 9000 × g for 15 min and filtration (0.22 µm; GHP Acrodisc 25 mm syringe filter; PALL) to remove bacterial cells and biotite particles. For the pH, the same procedure described above for abiotic weathering was followed with the bromocresol assay. Finally, to measure siderophore production, the liquid CAS assay procedure73 was used. In brief, 100 µL of filtered culture supernatant was mixed with 100 µL of CAS-Fe(III) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance was subsequently measured at 655 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, model iMark). The decrease in the O.D.655nm from 0.4 to values under 0.35 (corresponding to a change in medium coloration from blue to green and then yellow) is indicative of the presence of siderophores.

Kinetics of siderophore production, acidification, and weathering of biotite

Strain PML1(12) is known to acidify the medium when incubated in BHm and to produce the siderophore rhizobactin when incubated in ABm-Fe. However, no decrease in pH and no presence of chelating molecules were observed in the culture supernatant after 7 days of culture with the WT strain in either medium (i.e., BHm or ABm-Fe) with biotite particles <100 µm. To clarify the potential reactions occurring in a time-dependent way, a kinetic analysis was performed to investigate how the solution chemistry and physiology of strain PML1(12) changed during incubation. Kinetic experiments were performed only in the presence of biotite particles <100 µm (i.e., particles <20 µm; 20–50 µm and 50–100 µm). Non-inoculated and no mineral conditions were used again as controls. The samples were prepared by following the procedure outlined in the “Biotite biotic weathering assay” section. At each time point, each tube was sacrificed for analysis. The bacterial growth; concentrations of Fe, Al, Mg, Mn, and Si in solution; pH; and siderophore production were determined every 8 h over a four-day period using previously described procedures. For the experiments performed in the BHm medium, the glucose, and gluconic acid concentrations were also quantified using the Enzymatic BioAnalysis test (R-Biopharm/Roche) without replication. The absorbance was measured at 365 nm for glucose quantification and at 340 nm for gluconic acid quantification. In both cases, the concentrations of glucose and gluconic acid were determined according to a calibration curve.

Inhibition of siderophore production by element release from biotite

The production of siderophores is known to be finely regulated by the concentration of iron in solution. However, they have been demonstrated to be involved in the chelation of many other divalent and trivalent cations, such as Al3+, Mg2+, or Cr3+63,74,75. To evaluate the ability of Al3+ or Mg2+ (both contained in biotite) to inhibit siderophore production, the WT and mutant strains (i.e., rhiE::Gm) were incubated in liquid ABm medium with increasing concentrations of Al (using AlCl3) and Mg (using MgO) (i.e., 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3 mg/L). After 3 days of incubation, the siderophore production was measured using the CAS test, as described above.

Usually, only one element at a time (i.e., Fe, Mg, or Al) is used to evaluate the inhibition of siderophore biosynthesis, and iron-containing minerals or rocks are rarely considered. In the context of mineral weathering, iron can be released from the crystalline structure with other elements and metals that could impact the production and activity of siderophores. In this context, we conducted an experiment using a solution obtained after the abiotic weathering of the biotite as the culture medium. For this purpose, 100 mg of 200–500 µm biotite particles were introduced into tubes and autoclaved at 121 °C. After this autoclaving treatment, 5 mL of a modified version of the ABm medium adjusted to pH 2 with HCl (ABm devoid of iron and phosphate buffer) was added to perform an abiotic attack (i.e., acidolysis). The tubes were incubated at 25 °C with shaking (150 rpm), and the shaking was stopped at regular intervals to obtain solutions (abiotic dissolution solution, ADS) with different levels of biotite dissolution. After 0, 1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5 h, the ADS solutions were recovered through centrifugation (9000 × g; 15 min) and filtered (0.22 µm; GHP Acrodisc 25 mm syringe filter; PALL) for analysis via ICP‒AES to measure the quantity of Fe, Al, Mg, Mn, and Si released from biotite. To evaluate the production of siderophores by strain PML1(12), the pH of these solutions was adjusted to 6.5 using AB buffer (KH2PO4, Na2PO4 2·H2O). For this purpose, the culture medium was reconstituted as follows: 160 µL of the ADS solution (for each solution generated after abiotic dissolution of biotite) + 10 µL of AB buffer + 20 µL of mannitol (2 g/L final concentration). This culture medium derived from biotite dissolution was distributed in a 96-well microplate, and 10 µL of bacterial inoculum was added. The 96-well microplates were incubated at 25 °C for 3 days at 25 °C. Then, the microplates were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 min, and 100 µL was used to determine the siderophore production (as described previously).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in R software76 by the help of tidyverse packages. When triplicate samples were used, differences between sample’s means (growth, pH, CAS assay and weathered elements) were analyzed by ANOVA and TukeyHSD tests.

Responses