Sustainable production of CO2-derived materials

Introduction

Currently, carbon dioxide (CO2) is the most abundant greenhouse gas (GHG) populating the atmosphere. Furthermore, CO2 has been made directly responsible for climate change, based on the concept of global warming potential (GWP). The GWP is the ability of certain compounds such as GHGs to absorb energy (radiative efficiency), during their effective time in the atmosphere (lifetime) that cause a warming effect. The GWP is used to report GHG emissions normalized in terms of CO2, as CO2-equivalent or CO2-e. Based on the 100-year GWP, the fossil fuel use and industry contributes 64% of the total global CO2 emissions1.

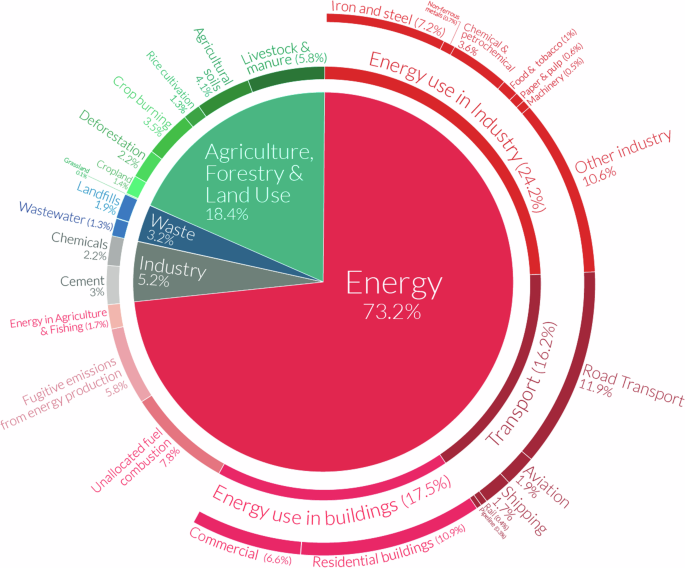

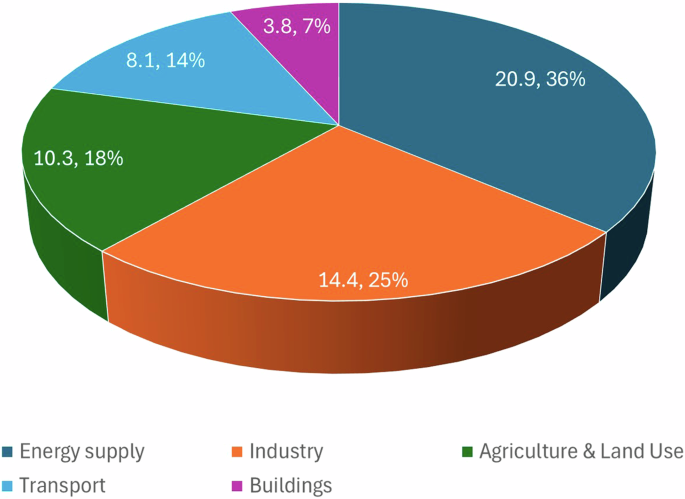

In 2022, the total global emissions of GHGs were 59 GtonCO2-e/year2, while those of CO2 were 37.2 GtonCO2/year3. The most recent sectoral/sub-sectoral emission data corresponds to that of 20192,4, and is reported in terms of CO2-e. The energy sector is responsible for the largest portion of GHG emissions, representing 24% of the total direct GHG emissions plus another 10% due to other energy transformations and fugitive emissions. The emissions from the transport and industrial sectors follow with 14% and 11%, respectively. Agriculture and fishing account for around 7% and wastes for about 6%5. The magnitude of the emissions reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) differed from the reported in Ref. 5 due to the differences in the sectors boundaries. For the IPCC, the energy sector generated 34% of the 59 GtonCO2-e emissions (20 GtCO2-e), 24% (14 GtCO2-e) from industry, 22% (13 GtCO2-e) from agriculture, forestry and other land-use, 15% (8.7 GtCO2-e) from transport and 6% (3.3 GtCO2-e) from buildings2. IPCC also pointed out that if the indirect energy-related emissions from industry and buildings are accounted for within these sectors, their contribution increased to 34% and 16%, respectively, and made the industry the largest emitter followed by energy. Five subsectors were discriminated for the energy sector namely, electricity and heat (69%), oil and gas (13%), coal mining (6%), oil refining (3%), and other (8%). Meanwhile, for industry, the six subsectors were indirect emissions (30%), metals (16%), chemicals (14%), waste (12%), cement (8%), and other (22%). The comparison of the data presented in 2016 Fig. 1 with that of 2022 in Fig. 2 reveals marginal progress in energy and industrial decarbonization though the rate of emissions growth is perceived as being decreasing. It should be noticed that boundaries for indirect emissions of some industrial subsectors in Fig. 1 differ from those defined in Fig. 2, as mentioned already.

Detailed sectoral 2016 GHG emissions (Reproduced from338).

2022 GHG emissions, by sector (Data, in GtonCO2-e/year from4).

An orchestration of coordinated actions throughout supply chains is needed to reduce industrial emissions. Some of these actions have been pointed out by the IPCC, including energy and materials efficiency, circular material flows, changes in production processes, product functional replacements, demand management, etc. It was also emphasized that regarding production and use of chemicals, the emissions abatement would need to rely on life cycle considerations and might require the incorporation of recycling, fuel and feedstock switching, carbon sourced through biogenic sources, and, emissions mitigation technologies (e.g., Carbon Capture and Utilization, CCU; direct air CO2 capture, DAC; and Carbon Capture and Storage, CCS)5.

The urgent need for emissions mitigation started to consolidate in 2015 when 196 countries subscribed to an agreement in Paris that set the basis for the Net Zero Initiative and demanded a reduction of at least 40% of the 1990 baseline emissions, by 20306. The rulebook for this Paris Agreement was completed in 2021 with the signing of the Glasgow Climate Pact by all the states belonging to the United Nations (UN) during the 26th UN Climate Conference (COP26)7. The forests and oceans natural capacity for sinking carbon emissions has long been overpassed by GHGs emission rate, jeopardizing environmental sustainability due to GHGs atmospheric accumulation. The continuous increase of the accumulation rate is the reason for the COP26 to limit global warming not to exceed 1.5 °C, by 2050.

Thermal energy is typically generated by fossil fuel combustion to drive certain chemical processes, emitting corresponding amounts of CO2. The reduction of environmental carbon (decarbonization) caused by the chemical industry requires the development and implementation of multiple new technologies, to capture (CC), store or sequester (CS), or utilize (CU) the produced CO2. Utilization might involve chemical conversion, recycling, or direct applications of CO2. Additionally, the chemical industry is also considering the elimination or replacement of any process emitting CO2. Any decarbonizing strategy would need to consider all these carbon capture, utilize and/or store (CCUS) technologies and carefully select their incorporation and application within their processes. The creation of revenues by the emitting businesses through the use of CCS technologies is very limited while the incorporation of utilization technologies might generate desirable profits that could be reinvested in the development of more effective and efficient CCUS process technologies. Additionally, utilization of the emitted CO2 in the production of long-lasting products and materials could result in negative emissions technologies (NETs)8,9,10,11,12, if low-C or renewable energy sources are employed13. Furthermore, integration of these processes within circular loops that also minimize waste generation could provide a suitable platform for an environmentally sustainable economy14,15,16,17.

The circularization of the materials flows and/or the supply chain is seen as an approach towards seeking sustainability. A CE appears as an integral evolution from linear supply chains towards an improved version for protecting the environment and managing resources. In fact, in a CE nothing is wasted, natural resources are managed sustainably, and biodiversity is protected, valued and restored in ways that enhance our society’s resilience; and our low-carbon growth has long been decoupled from resource use, setting the pace for a safe and sustainable global society18. A complete graphical representation of resources and materials management within the CE is the ‘butterfly diagram’, provided by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s19. The Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency has suggested one of the most comprehensive CE models comprising ten approaches for circularity: Refuse, Rethink, Reduce, Reuse, Repair, Refurbish, Remanufacture, Repurpose, Recycle, and Recover energy (Re-X type approaches)20.

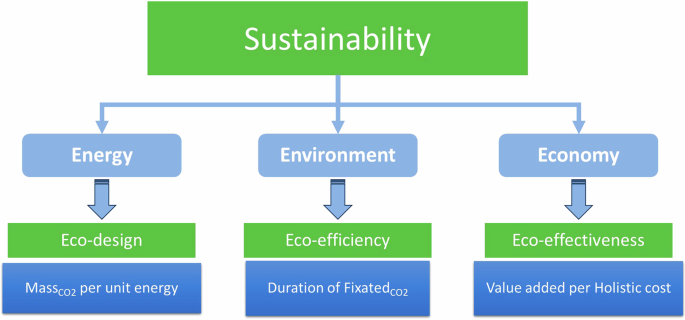

Sustainability has been defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”21. The sustainability components (social, environmental and economic) involve both production and end-use of resources, matter, products, and energy. An environmental and economic conscience is needed to manage those components and so, to preserve the wellbeing of the future generations. In the circular integration of technologies, environmental sustainability has to add up economic sustainability to ensure human development growth. Although a CE is expected to create new businesses and job opportunities, save costs, reduce price volatility, and improve supply security22, it is not per se a guarantee for sustainability. Originally, CE was proposed as driven by renewable energy23 but nowadays any other carbon-neutral energy resource is well accepted. Technologies with either carbon neutral or negative emissions and conceived circularly would have good possibilities to achieve environmental, energy and economic sustainability24. The monitoring and assessment of sustainability of circular approaches requires of comprehensive methodologies with suitable holistic metrics25.

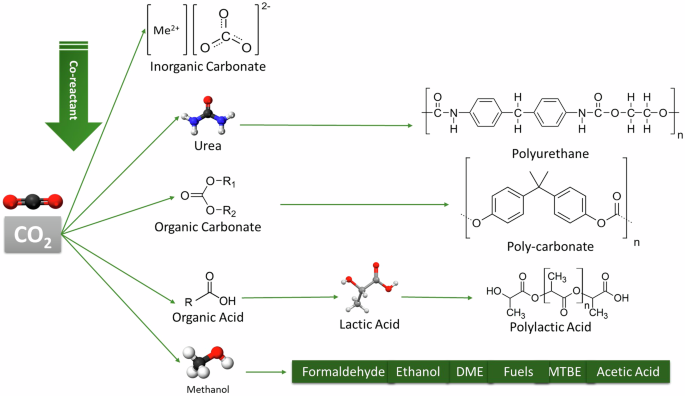

This work revises the published literature to identify the R&D activities associated with CO2-derived materials and those enabling their sustainable production. Among the variety of potential candidates to be produced from CO2, a selected set of inorganic and organic materials will be examined. These are exemplified in Fig. 3.

Considered CO2-derived materials and products.

Production pathways

As mentioned above, processes for CO2 conversion, into products and materials with longer life-cycle and using C-neutral energy sources are needed to pave the way towards a sustainable future. Although this work focuses on the chemical conversion of CO2, this compound, once emitted or at the emission source, needs to be captured first to be utilized later. Therefore, the crucial role of CC in meeting COP26 or Net-Zero goals is unquestionable. Nevertheless, the numerous reported chemical reactions of CO2 that can yield valuable products and materials provide a wide range of pathways worth considering for finding profitable ways of utilizing CO2. Regardless of the large efforts on R&D and technology development work, very few have reached a commercial scale. This review will show that most of the published literature corresponds to tests performed far from being optimal or under efficient use of energy, and in rare instances, the benefits of C-intensity or C-footprint, if any, have been reported.

The cumulative knowledge and results indicate that a potential for the production of both inorganic and organic materials and products that can retain carbon in their matrix for a long period of time exists and is high. A preferred set of reactions are those that incorporate the whole CO2 moiety into another molecule or macromolecule, e.g., carbonation, carboxylation, addition, etc. Meanwhile, another interesting set of reactions is rendering building blocks to produce materials and indirectly store carbon. An overview of the reported work on these reactions follows.

Inorganic materials via carbonation

The production of carbonate, bicarbonate, or carbamate materials can take place by carbonation of alkaline or alkaline earth elements or their oxides. This reaction occurs naturally as part of the Earth C-cycle to fix carbon in the form of minerals, i.e., mineralization. Sequestration technologies also take advantage of this reaction to store CO2 in geological formations. The relevance of this reaction for sequestration purposes has given rise to significant efforts on R&D and technology development that have been reviewed in books26,27,28 and articles29,30,31,32,33,34,35.

The industrial application of these reactions for the commercial production of inorganic materials requires facing the challenges and filling the knowledge and technology gaps already identified for natural fixation or sequestration. Currently, carbonation is carried out by the reaction of an acidic aqueous solution of CO2 with silicate minerals (e.g., olivine, wollastonite, and serpentine), i.e., mineral carbonation, MC. The acid media promotes the leaching of alkaline/alkaline earth metal (Me) cations from the mineral matrix to react with the dissolved CO2. The pH of the reacting mixture increases due to protons consumption while the carbonate precipitates (see reactions R.1 and R.2).

The main advantage of carbonation is its favorable thermodynamics but reaction rates are very slow, i.e., reactions exothermicity (ΔH298 K = −60 to -100 kJ/mol) does not compensate the kinetic limitations36. Carbonation yields stable solid inorganic materials, in which CO2 could be stored almost permanently. Therefore, the kinetic restrictions need to be overcome, to enable commercial industrialization. This kinetic drawback is caused by the slowness of cations release from the mineral, which depends on the mineral type and composition, element, pH, and temperature and has been addressed through different approaches, such as minerals pre-treatment and activation, raw material and CO2 source selection, and reacting phases (gas-solid or aqueous)32. For instance, reaction kinetics can be accelerated by raising the reaction temperature though for aqueous phase reactions, the higher the temperature, the higher the CO2 in the gas phase. Thus, a pressurized fluidized bed was suggested for the Abo Akademi route for improving kinetics and energy efficiency37. Actually, energy intensity is another drawback of the processes since it is not low and it is aggravated by compression of the CO2 feed, waste and mineral treatments (mechanical separation, crushing, milling, and grinding), materials flow management and/or process conditions38. Process integration and intensification have been considered in the search for energy efficiency improvements, e.g., energy intensity could be diminished by balancing the energy required by metal extraction/digestion with that released from the exothermicity of the carbonation reaction, in an autothermal reactor. A mathematical model was applied to define particle size, solids loading, pumping rate, and reactor dimensions, for autothermal operation and to maximize carbonation efficiency and heat recovery39. Mg was the focus of attention and serpentinite and metaperidotite minerals, which are Mg-rich were considered40. Magnesium extraction from these minerals could be facilitated by ammonium salts39 and could be incorporated as a first step, prior to carbonation as a way to overcome kinetics limitations. Although minerals might represent a cheap source of raw material, the considered approaches to overcome the kinetic limitations (temperature/heat, activation e.g., mechanical, chemical, or biological) imply an unfavored material balance (stoichiometry), demanding a large amount of mineral or wastes to be handled per unit of CO2 to be removed (2-3 tonrock/tonCO2). In summary, both energy and carbon intensity vary in a very broad range due to the fact that carbonation can be applied close to either the emitting source or to the feedstock supplier, and also a variety of feedstocks (wastes, minerals and/or compounds) can be carbonated.

The development of carbonation technologies (for Ca and/or Mg) started in the 1990’s decade, at Los Alamos National Laboratory41 and evolved at the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) leading to the direct aqueous mineralization method42,43,44. The process consists of the two steps described already namely, metal ion dissolution from a metal-rich mineral, followed by carbonate precipitation45. At the time this development took place, no effort was devoted to energy integration, none to the use of neutral-carbon energy source. Instead, operations using energy from a 1-GW coal-fired power plant resulted impracticable, due to the large CO2 emissions44. Additionally, the low value of the products (probably due to supply/demand market balance) and the high production costs (including logistics associated with the move of high volumes of minerals)46 call for cost-effective technologies with minimal environmental impact, to improve feasibility.

Worldwide carbonation R&D progress has been associated with CCS applications, and more particularly with CS in situ geological formations. However, the economic impact of carbonation on a CS application is not very promising: “The best case studied so far is the wet carbonation of the natural silicate olivine, which costs between 50 and 100 US$/tonCO2 stored and translates into a 30–50% energy penalty on the original power plant. When accounting for the 10–40% energy penalty in the capture plant as well, a full CCS system with MC would need 60–180% more energy than a power plant with equivalent output without CCS”47. The high costs, as reported for CS applications48 led the perception of a lack of economic viability, slowing down both carbonation development and implementation49,50. Some lessons learned include the effects of energy intensity51, as well as of raw materials and of waste disposal costs on process economy52. An increase in the number of process steps (two to four), to enhance product quality was thought as a way to improve the carbonation economy. Although technically proven, it did not succeed economically53. Cambridge Carbon Capture incorporated other improvements to boost process economy54 and environmental impact55, which include a cheaper mineral56 and CO2-source57, alkaline digestion as a pretreatment step58,59, valorizing all products and by-products60, and co-production of electricity61. The main learnings from this company when boosting the technology economy54 were the valorization of all products, including high purity metals, silica, zero-carbon calcium & magnesium oxides and carbonate mineral powders60, and the production costs optimization, by using cheap raw materials56. In general, industry has pursued the cheaper materials approach, e.g., the carbonation of red mud (bauxite residue), cement bypass dust, cement kiln dust, waste cement, fly ash, construction and demolition mineral waste, steel slag, blast furnace slag, electric arc furnace slag, mine tailings, Galligu, contaminated soils, municipal waste incinerator ash, APCr, and water treatment sludge62. A reported competitive and environmentally amicable method produces calcium carbonate, metals (e.g., vanadium) and metallic nanoparticles (e.g., silver, copper, nickel, etc.), using by-products and slag from the iron and steel industry63. Carbonation was proven in Finland using CO2 (and CO) gas from the top of the blast furnace to convert the Mg from serpentinite rock to MgCO3. The integration to water gas shift reaction incorporates hydrogen and steam to the process that can be optionally operated with dry or wet gas flow. The metallic nanoparticles production showed overall environmental benefits when life cycle assessment (LCA) considered the use of dry gas flow55. Similarly, LCA has also shown the environmental advantages of producing nanoCaCO3 as an improver of mechanical properties of cementitious materials. In fact, the simultaneous production of NH4Cl when using CaCl2 as calcium source proved to reduce 60% the conventional Portland cement emissions, when cement was filled with 2 wt% of nanoCaCO364. In Singapore, LCA also proved that carbonation of serpentine with flue gas from incineration plants resulted in positive reduction in emissions, being the transportation of the mineral to the carbonation plant responsible for 50% of the emissions65.

Production of bicarbonate via electrochemical carbonation could also render value-added by-products such as hydrogen66 or electricity67. The sustainability possibilities of electrochemical carbonation are underpinned by the use of scrap metal source for the anode, seawater as electrolyte, industrially relevant gas stream and zero-carbon energy sources. An specific example has been given for the case of wasted aluminum foil in the anode to produce aluminum hydroxycarbonate mineral, which can be employed as cementitious material in the elaboration of concrete. The 2009 production rate of recyclable aluminum foil accounts for the capture of 20–45 MtonCO2/year through this reaction66. An improvement of the electrochemical cell performance was achieved by separating the graphite and aluminum components of the dual-material anode. However, even though the energy efficiency of the carbon capture and the current density of the cell could be improved, the capturing efficiency deteriorated. In fact, while a 1:4 C:Al ratio was originally attained on the dual-material anode, it decreased to 1:7 C:Al for the separated anode67. An additional value-added product from bicarbonate, ammonium bicarbonate can be obtained by its direct reaction with ammonia (NH3) in aqueous phase68.

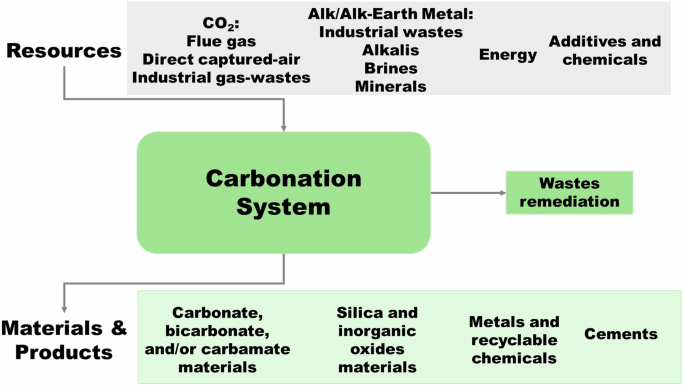

The potentialities and opportunities reside on technologies developed for ex situ carbonation, depending on their cost-effective optimization to overcome kinetic limitations and energy intensity (Fig. 4). Regarding raw materials, inorganic industrial wastes could be used as carbonation co-reactant69,70,71, providing logistic issues are not present or otherwise, economically overcome. Similarly, the direct use of flue gases as feedstock will eliminate the expensive capture step. Process intensification to allow the direct use of CO2‐containing flue gases72,73 will minimize investments on energy-intensive large-scale solvent capture54. This intensification approach would favor not only the economy but also the energy intensity and probably, the C-footprint, as well. Assuming that cost-effective technologies are developed, the size of the market will set the demand for the products. Unfortunately, in an incrementing offer scenario, the price will be forced to fall, affecting negatively the economy of the processes.

Carbonation potentialities.

Although the current uses and applications of these materials are numerous, new applications and uses should be developed to grow market needs and product demand, and to improve the competitiveness of the carbonation processes. The current uses of carbonates, bicarbonate, and carbamates include medicinal drugs, glass making, the pulp and paper industry, chemicals (e.g., silicates) and chemical applications, soap and detergents production, water softeners, glass making, textiles, photography chemicals, short-chain alcohol production, production of other salts, processing ores, nuclear applications (e.g., molten salts), skin care products, cosmetics, anti-fire products, climbing chalk, paints, plastics production, caulk industry, ink and sealant production, non-toxic food additive, fireworks, magnets, ceramic and porcelain manufacture, rat poison and fungicides manufacture, etc.74. CO2-derived inorganic materials find various applications in the building sector since they can be used as an ingredient in concrete production. Calcium carbonate is a raw material in the production of cement, and magnesium (Mg) or calcium (Ca) carbonates can be used as components of the filler (aggregate) or during the process of concrete curing. The production of aggregates can be based on the carbonation of Mg- or Ca-rich silicates, iron slag, and coal fly ash75. The debris after construction demolition, the crushed, recycled aggregate gathered from concrete can be subjected to carbonation and recycled as carbonated aggregates to increase density, lower water absorption, and improve concrete properties, including better flow and compressive strength76. Although the sustainability of cement, concrete, and cement replacement materials in construction has been a concern of the manufacturing sector, this concern only comes after factors such as technical performance, project delivery, and supply of materials. The simplest technique for concrete’s CO2 emissions mitigation that has already spread throughout the cement industry is the use of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). Besides carbonates that can be obtained from MC to produce aggregates glass powder can also be used77. In the case that silicates were used in MC, silica powder will be a by-product and an intermediate for the glass powder production. The use of recycled and secondary aggregates can contribute to reducing the carbon footprint and preserving natural resources78. Last but not least, carbonation can play a very important role in the recovery and production of critical materials and elements (CME), which are minerals, elements, and compounds that play a vital role in energy security (availability, accessibility, and affordability) and/or in the generation of clean energy79. Criticality is caused by a high demand, which could hardly be met by decreasing production or global offer. Since clean energy technologies require more minerals than those used by traditional fossil-based traditional technologies, the magnitude of CMEs consumed by the energy sector will increase, as the energy transition gets closer. This increase in CMEs consumption depends on the width of the deployed technology spectrum79. Among the typical carbonation-reactive elements, Li and Mg are CMEs and most of the discussed work concerned this type of elements (alkaline or alkaline earth metals, see also80,81). Studies for the carbonation of other CMEs have been reported82,83.

An increased demand for CO2-derived inorganic materials benefiting the market value and incentivizing the development of improved technology will pave the way for their sustainable production.

Urea production from CO2 and urea-derived materials

Urea (CO(NH2)2) is a naturally occurring amide material synthesized in mammals through protein metabolism. In the chemical industry, it is both a co-reactant as well as an intermediate in many reactions. Its main use is as a source of nitrogen in fertilizers. Fertilizers consume about 90% of the global production of urea84, emphasizing the relevance of this product though fertilizer production and excessive use may have environmental consequences. Additionally, two other classes of materials use urea as a building block: urea-formaldehyde resins and urea-melamine-formaldehyde85.

The industrial production of urea represents the largest CO2 volume consumption, by any CO2 conversion processes (about 130 MtonCO2/y)86. Urea is synthesized from the reaction between ammonia (NH3) and CO2, in a two-steps process, developed in 1922: the Bosch-Meiser process84,87, described by reactions R.3 and R.4. While carbamate formation (R.3) is an exothermic reaction, carried out between liquid NH3 and gaseous CO2, its decomposition (R.4) to yield urea is endothermic.

Ammonia synthesis is an energy intense technology due to the high severity of the operating conditions employed and to the large hydrogen consumption. Hydrogen production is both energy and carbon intense process technology as well. Thus, ammonia synthesis (partially due to the steam reforming production of hydrogen) is one of the four top chemical processes together with benzene, methanol, and steam cracking responsible for the high CO2 emissions of the chemical industry88. In some instances, part of the CO2 produced in the ammonia plant is recycled to the urea plant though this is not the most common practice. The use of green (in the decarbonization glossary, a brown process technology uses heat and energy generated from the combustion of fossil fuel; in a blue process technology CC, CCS, and/or CCU technologies have been incorporated to mitigate emissions; and in a green process technology the heat and energy is generated from renewable, low-C or neutral-C sources. In some instances, gray is used as an intermediate emitting scale between brown and blue.) ammonia to produce urea will represent a big step towards sustainability. Vast R&D efforts have been made for the decarbonization of ammonia production mostly to the development of processes that could take place at ambient or less severe conditions. In this regard, electrochemical synthesis of ammonia is one of the green alternatives that has been receiving attention and R&D efforts are progressing in this area89,90,91,92,93,94. Announcements from the major licensor of ammonia synthesis technologies indicate the great advances being made on decarbonizing production plants. Ammonia plants are being converted from brown to blue, and construction of new plants for green NH3, even at commercial scale have been announced (95,96,). These efforts together with those made for the production of green hydrogen underpin a short coming of green NH3 production, which discussion will fall outside the scope of the present work.

Apparently, opportunities to open pathways towards the large scale production of sustainable urea and its derivative materials seem to be around the corner but not free from barriers and limitations. A prospective LCA study revealed that complete decarbonization of the ammonia industry by 2050 is unlikely97. The electrolysis-based ammonia provided either renewable or low-C electricity might offer a promising pathway. The limitations mentioned in the study include the need to reduce urea demand, potential growth in ammonia as a fuel, reliance on CO2 transport and storage, expansion of renewable energy, raw material scarcity, and the longevity of existing plants97. An LCA evaluation of the integration of the urea production plant to a steel mill, for using off gases and surplus streams (H2, steam, etc.) showed an emission reduction better than 65%, when renewable energy (wind) was employed98. An LCA addressing the interplay between energy consumption and GHG emissions identified the areas of materials preparation stage, synthesis stage, and waste-treatment stage as the point of attention for improvements. Specific attention should be paid to steam generation, replacement of fossil fuels burning, hydrogen production and energy efficiency measures99. As mentioned above, an approach for materials flow optimization is the use of captured-CO2 from the hydrogen plant (of the ammonia synthesis unit). The environmental impact of the capture units is mainly due to exergy destruction, as shown in an exergoeconomic analysis of this unit. All components exchangers, absorber tower and stripper require energy balance/integration upgrades. The optimization to minimize the total costs and maximize the efficiency situated the decision variables on the lean mono-ethanolamine (MEA) temperature and loading, and on the heights of the absorber and the stripper100.

Considering the end-use of urea as fertilizer, the environmental impact of its agriculture application becomes relevant. One first argument, on the application of LCA in this area was to compare indicators expressed in terms of kg of nutrient and not per kg of product as it is typically done in LCAs. The evaluation of 18 environmental indicators led to the conclusion that synthetic fertilizers (including urea) were better than organic-derived ones101. An integrated LCA and Emergy (Emergy is a thermodynamics-based concept to provide a holistic environmental accounting system. An emergy assessment identifies and measures all energy and matter inputs into a given system, to evaluate the environmental cost of a given resource, expressed in a common unit, the solar emergy joule (sej). The unit emergy value, UEV is the emergy per unit product.) Accounting (EMA) study evaluated the environmental costs and impacts of resources (including urea) in agricultural production. EMA is applied in the estimation of environmental support to resource generation and provision. Thus, EMA provides a parameter, the Unit Emergy Value (UEV)102 to measure the environmental efficiency of a production process. A high UEV means lower environmental efficiency, which should not be ignored or disregarded. Consumption of non-renewable resources contributes to a high UEV. The reported data revealed the gaps from a sustainable agriculture and the need for incorporation of renewable resources and sustainable management103. Another LCA study of the use of urea as fertilizer concerns the production of hemp to derive a bio-based binder to be employed as a component of building materials. The results indicated that production of urea was the top contributor to carbon emissions (21%)104, largely affected for the energy consumption (30.1 GJ/t urea99). The more recently developed blending controlled-release urea has demonstrated both economic and environmental advantages over the common urea, by increasing the yield of the agronomic product and decreasing the associated emissions, respectively105. A global perspective of the urea (fertilizer) industry was assessed by first evaluating the environmental impact of an urea production plant based on coal gasification. The GWP of such plant was estimated to be 0.714 ton CO2-eq/ton Urea106. At a global scale, besides the GHG impact, eutrophication and acidification are also badly affected by this type of urea plants. In order to improve sustainability indexes, replacing fossil-based electricity by renewable sources, replacing upstream processes (such as natural gas sweetening) by eco-efficiency ones, and use of renewable feedstocks/raw materials were recommended107.

The polymerization of urea and formaldehyde is a very complex reaction, involving mainly two types of reactions: addition and condensation reactions. The hydroxymethyl moieties oligomerize via condensation reactions, followed by cross-linking of the formed oligomers. Meanwhile, the addition reactions occur directly between the two compounds, urea and formaldehyde, forming mono-, bis-, or tris(hydroxymethyl) urea108,109. Some process conditions such as, the temperature and pH of the reaction mixture and the formaldehyde-to-urea (F/U) molar ratio110 are determinant of the produced resin properties, e.g., the extent of branching, the reaction rate and the proportion and type of chemical linkages111. The most important application of the urea-formaldehyde (UF) resins is as wood adhesives for the manufacture of plywood, particleboard, fiberboard, and oriented strand board112,113, capturing more than 85% of the global adhesive market ( ~11 Mton/y)114. The industrialization and commercialization boom of UF resins took place during the second half of the XX century, particularly for its use as adhesives for plywood and particleboard, after the World War II and the housing efforts of affected countries115. Despite these popular uses of this resin, formaldehyde is released over time, from the manufactured wood representing not only a source of indoor pollution, but also threats to human health upon exposure41. Extensive research on these formaldehyde emissions has been carried out, reported and reviewed116,117,118,119,120,121,122. The LCA studies (ref. 123) confirmed that regardless of the low GHG emissions of the overall UF production process, it has large impact on human health, acidification and eutrophication aspects. The efforts to stop formaldehyde emissions have been made through modifications to the polymerization conditions and to the manufacturing processes, leading to not only a highly mitigated problem but also to improved products114,116,124,125,126,127. Finally, the production of green or renewable formaldehyde and of the UF resin have also received attention through routes from CO2128,129,130,131 and from biomass132,133,134 though its developmental maturity and possibilities for commercial implementation are not as high as those for urea. LCA studies pointed out that composites formed by bio-based adhesives and UF resin exhibit advantageous functional properties (e.g., flame retardant, mildew resistant, water resistant, high mechanical properties, thermally repairable, biodegradable, and low-cost), together with a lower environmental impact135,136. Contrarily, another LCA study concluded that compared to the traditional cementitious materials, the production of bio-cementitious materials has greater environmental impact, particularly on eutrophication137.

Incorporation of melamine (C3H6N6) was one of the modifications pursued in the search to improve the stability of the UF resins138,139,140,141,142. Melamine is a cyanamide trimer appearing as a white solid material. The pure compound is highly toxic and drastic measures are in place for its regulation and uses143 though as such it has multiple uses and application in tableware and building materials144. Besides, these uses and applications of the pure compound, its incorporation in the resin broaden the applications for the improved material145,146,147,148,149,150. The advantages on low cost (or cost-effectiveness), isotropicity, high processability, high strength and high dimensional stability have contributed to the preferential use in the construction industry, interior decoration, shopfitting industry furniture, construction, reinforced wood panels, etc. Besides these economic and functional aspects, LCA also indicated some of the environmental advantages of the melamine-UF resins, including lower contribution to photochemical oxidation, ecotoxicity and human toxicity151. The expectations for a sustainable melamine production lays on routes starting from urea (e.g.,152,153,154) or from CO2 and/or (green) NH3 (e.g.,155,156,157). LCA of the manufacture of wood products and panels indicated that production of UF resin and electricity consumption are the main factors contributing to the environmental impact158,159.

Organic materials via carboxylation

The incorporation of the whole CO2 moiety in organic molecules (carboxylation reaction) can render acids160, esters, lactones, carbamates161,162,163 and carbonates164. Thus, carboxylation is the chemical reaction for transferring or incorporating a carboxylic group (-COO) into an organic molecule. For the purpose of this work, the carboxylation agent will be carbon dioxide. The thermodynamic stability of CO2 makes its chemical reactions to be energy intense and among these reactions, carboxylation is typically the least intense particularly, in comparison with its reductive decomposition (CO production or lower C-oxidation state products). Additionally, carboxylation reactions could lead to the production of compounds with a high energy value, e.g., strained cyclic molecules, unsaturated compounds, or syngas/hydrogen. Carboxylic acids, esters and organic carbonates can be employed as building blocks of biodegradable, low toxic, renewable materials, such as polycarbonates, polyacids and polyurethanes. These plastics represent decarbonized options to replace their corresponding fossil-derived counterparts while fixating CO2 for longer periods of time. Thus, carboxylation reactions can be used for the massive utilization of CO2 in producing a myriad of commodity materials as well as material specialties. Hydrocarboxylation renders carboxylic acids or esters from the reaction of olefins and/or alcohols, CO2, and H2165, which can be polymerized to produce versatile poly-acids or poly-ester materials166,167.

Dialkyl carbonates can be produced by the direct reaction of CO2 with alcohols. Typically, the reaction of CO2 with alcohols occurs under base-catalyzed conditions and requires high pressures to yield dialkyl carbonates (R.5), studied catalysts include tin oxide and zirconia168 and alkoxides of Sn (IV) and Ti (IV)169.

A combination of acid and base activation of methanol has been proven as a successful mean for the formation of dimethyl carbonate (DMC), using several different catalysts, e.g., [Nb(OMe)5]2170, hydrotalcite171, CeO2172, Y2O3173, or ZrO2174. The need for amphoteric pair of sites seems to be of common acceptance. The acid sites are needed to promote the methylation from methanol and the basic sites to activate CO2. Although, some of the tested catalysts are highly selective, the reaction of methanol with CO2 is limited by equilibrium175. This reaction is exothermic (ΔH°298K = −27.90 kJ/mol) but it does not occur spontaneously at ambient temperatures and pressure (ΔG°298K = 26.21 kJ/mol)173. This thermodynamic limitation calls for intensification of the process and reactive distillation has been suggested as a feasible alternative to pursue. The proposed configuration increased methanol conversion in one step from 10% to 99.5% and an additional reduction in energy consumption pushed the process closer towards sustainability176. Besides the thermodynamic limitations, product recovery represents another process hurdle due to the azeotrope formation between DMC and methanol. Azeotropic separations typically are carried out by extractive distillation that involves high energy and solvent consumption. Ionic liquids have been suggested as a solution for product recovery and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis-(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide has been found to generate up to 70% savings in total annual costs, compared to other evaluated ionic liquids. All the evaluated solvents had positive environmental perspectives though these were affected by their thermal decomposition177. The electrochemical reaction, in the presence of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide and of potassium methoxide has been under study, again product recovery is the main drawback. Compared to the conventional carbonylation reaction (ENI process), its environmental impact is greater178.

The industrial demand for DMC have been pushed to significantly grow, by its non-toxicity, chemical properties, and derivatives (e.g., aromatic polycarbonates, solvents and fuels)179. However, the largest quote of this demand as methylating agent180,181 needs to be phased out due to CO2 releases. Some recent efforts have been devoted towards the development of sustainable methylating processes182. The advantageous properties together with the growing market are strong drivers to find (and develop) sustainable production pathways. An environmentally advantageous route183 has been found to be the methanolysis reaction with urea to produce methyl carbamate, which could react with methanol to yield DMC, in a second step184. The energy requirements for product recovery represented the greater contributor to environmental impact, followed by the production and procurement of the starting raw materials183.

The sustainability of the DMC producing pathways was evaluated, using LCA on six different pathways, from which CO2 was a raw material in three of those (P.4, P.5 and P.6): P.1. HCl coproduction from methanol and phosgene; P.2. via methyl nitrite (from methanol and NO) coproduction of CO and recovering of NO; P.3 reaction of CO and methanol; P.4 NH3 coproduction from urea and methanol; P.5 ethylene glycol (EG) coproduction from ethylene oxide and CO2; P.6: reaction of CO2 and methanol185. Environmental impact indicator included human, terrestrial and aquatic toxicity, GWP, and the potentials for ozone depletion, for photochemical oxidation and for acidification. The environmental assessment, based on the stoichiometric reactions positioned P.3 and P.6 as the greenest pathways while P.5 was economically better. Regardless of favorable P.6 results, a suggestion to abandon it was made based on being industrially unfeasible. Meanwhile, the overall results (economic and environmental) support the sustainability advantages of P.5, and in a lesser extend of P.4185. The processes of P.4 and P.5 were simulated to generate optimized data that was then input into an economical and environmental assessment, to evaluate additional sustainability indexes such as material index, energy index, and ecoefficiency. The sustainability indexes for P.5 resulted better than those of P.4 though the results might be different for P.4 if the relevance of the environmental index is increased on a cradle-to-gate basis186. The environmental advantages of EG co-production pathway have pushed further improvements to enhance process economy. One of these improvements is the recycling of by-products, which also contributes to minimizing waste generation. Thus, a 20% increase in DMC yield was attained by recycling EG with highly positive consequences in the economy since the net present value was increased five-fold and the payback period was reduced from 8.3 years to 3.6 years. This recycling, in addition to the economic benefit also brought a 10% reduction in environmental impact187. A totally different approach to select a specific pathway and to generate an intensified process scheme for the selected pathway consisted of an algorithm to optimize the operational feasibility, economics, life cycle assessment factors and sustainability measures. In the first step of process synthesis–design, the schemes were created and then TEA and LCA were applied for their evaluation, to identify process hot-spots and design targets requiring improvement. The operability and control of the more sustainable intensified alternatives were also addressed to formulate the best intensified option188.

Polyurethanes (PUs) are conventionally synthetized by the reaction between the isocyanate NCO group with polyol OH groups. Isocyanates can be obtained from carbamates189, which can be produced from the reaction of DMC with amines190, for an alternative route to PUs production. Other routes for the production of polyurethane use the reaction of DMC with aliphatic diols to form oligocarbonate diols and also polycarbonates191,192. PUs are broadly used in construction (e.g., sandwich and structure panels, spray in-place foam, thermal insulation boards) as well as in manufacture (e.g., sponges, seats, pillows, mattress, footwear, bezels and structural parts, cast objects, etc.). Further the reaction of isocyanates with CO2 expands applications for polyurethanes through the chemistry of oxadiazinetriones193. Although PUs are chemically inert and non-carcinogenic, they are flammable and the decomposition products are toxic, hazardous and in some instances lethal. Additionally, the production and some of the applications of PUs lead to human exposure to toxic and hazardous raw materials and/or compounds194. Therefore, environmental assessment needs to include these health impacts through a comprehensive analysis involving all the materials, products and compounds and all their life cycle stages. LCA has been applied to evaluate both human and eco-toxicity of different products and materials, for different life cycle stages. For instance, LCA of PUs production stage was reported for uses as building material195 and waterborne PU dispersions196. Regarding the assessment of the economic and environmental impacts of PUs during their service life cycle stage, some examples follow. An LCA evaluation on the PUs insulation applications showed beneficial energy savings for buildings (10–15% with emissions reduction of 30–35%197) during the service life cycle stage but a high environmental impact during the production life cycle stage198. LCA showed that the addition of PU to gypsum ceiling tiles led to a 14% reduction in energy consumption, a 14% reduction in CO2 emissions and a 25% reduction in water consumption199. Additional reductions from the PU-containing tiles include 9% in ground and water acidification, 9% for eutrophication and 31% for non-hazardous waste200. However, the considered production pathways fall away from the scope of the present work and the employed methodology concerns strictly the PU use as a component or part of a composite in building or manufacturing materials. The search for a sustainable production pathway of PUs has been gaining traction and both biomass and CO2 as starting materials have been the subject of these R&D efforts. In the case of biomass, synthetic pathways as well as new composite formulations have been addressed. The economic and environmental advantages of some of these pathways have been reported as well201,202,203,204,205,206.

Organic carbonates or polycarbonates can be obtained from the reaction of CO2 with epoxides, for which organic bases, alkali187 metal halides, metal complexes, ionic liquids, zeolites, and metal oxides have shown promising catalytic activity though their stability and/or recovery represented challenges to industrial scaling207. Cyclic carbonates are economically and environmentally relevant building blocks of polycarbonates, other polymers, and fine chemicals production, which are used as electrolytes and aprotic polar solvents. Urethane groups, which are the building units of thermosetting plastic networks can be formed from the reaction of cyclic carbonates with bifunctional primary or secondary amines208. Bayer reported its work on the development and scale up of catalysts and processes for the copolymerization of epoxides and CO2, which products obtained vary from polyethercarbonates to polycarbonates, passing through polymers with alternate sequences of polyether with carbonate bonds. The different conditions affecting the kinetics of the reaction as well as catalyst selectivity were studied209,210. A recent LCA study demonstrated the environmental advantages of using these thermosetting polymers as binders for replacing Portland cement, in concrete formulations for construction applications211. Applications of polycarbonates, polyacrylates, and polyurethanes as insulators, building materials, shoes and clothes, solar panel components, etc. are emerging212.

Terpolymers and polyalkylenecarbonates were reported to be produced from CO2 with cyclic acid anhydrides and with epoxides, respectively167. Applications of these materials have been developed for the ceramic and building industries, as pore-forming agents and insulating foams, respectively212.

Enzymatic biocatalysts213,214,215 and ionizing radiation216 have been employed as a way to address the energy intensity of the carboxylation processes. Salicylic acid217,218,219, malonic acid219,220,221,222, and amino acids216 have been obtained through radiation-induced carboxylation reactions.

The production of low carbon energy carriers, products and materials brought about CO2 incorporation into renewable feedstocks. Thus, as previously mentioned, organic carbonates might be the main products obtained from the reactions of CO2 with bio-feedstocks (e.g., glycerol223). The increasing surplus of glycerol from biodiesel production224 makes this molecule an economically attractive platform for different renewable chemicals and materials225,226. The manufacture of polyesters, polyurethanes and polyamides could benefit from the use of glycerol carbonate, which is also used as solvent, emulsifier, and chemical intermediate227. Glycerol carbonate is obtained from the reaction of glycerol with urea using as catalyst zinc salts228, lanthanum oxide229 and metal-impregnated zeolites230. The direct carbonation of glycerol with CO2, using tin complexes as homogeneous catalysts has been reported231,232. Some other examples and the economic and environmental impacts of these pathways have been mentioned above. Reports concerning a broad range of plastics can be found in201,202,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240.

Methanol production from CO2 and methanol derived materials

Methanol can be produced thermo-catalytically, from CO2 hydrogenation, as it has been demonstrated in Svartsengi, Iceland241. This demonstration plant is based in the Olah process, a single step process, licensed by Carbon Recycling International (CRI), as the Emissions-to-Liquids (EtL) technology242. This EtL technology plant uses geothermal energy, the CO2 captured from that geo-power plant and green hydrogen produced from water electrolysis, as per reaction R.6.

More recently (February 2024), CRI announced the starting-up of a larger plant based on the EtL technology, in Anyang city, Henan Province, China that will consume 160 ktonCO2/y to produce 110 kton of methanol243. Another single step option is the Lurgi process244, with subsequent improvements including addition of stages, reactors, heat exchanges, separators, etc.245,246,247,248,249. Meanwhile the CAMERE technology is a two-step process in which carbon monoxide is produced by CO2 reduction through the reversed water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction (R.7)250,251. This RWGS reactor is coated with water perm-selective membrane, to favor CO formation252,253. In the second step, hydrogen is added to produced methanol254, under typical methanol synthesis conditions (R.8).

All these process technologies exhibit severe drawbacks i.e., low conversion and poor catalyst selectivity, with multiple side reactions occurring on the conventional methanol synthesis catalysts that have been and are being employed. Another important drawback is inherent to the chemistry since water formation can be seen as hydrogen loss (attention should be placed to exergy comparative studies255). Therefore, methanol production from CO2 can benefit by technical and economical improvements on both catalysts and processes. Thus, new catalysts256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263, photocatalysts264, electrocatalysts265,266,267, biocatalyst268,269 and processes131,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282 have been proposed and some identified challenges addressed. So far, the desired levels of conversion and selectivity to overcome the economic limitations have not been achieved with the new reported systems. Some other efforts have been focused on CO2 recycling283 and energy efficiency284, which have been addressed through process integration to power plants. Additionally, the electrochemical route needs improvements on cell potential, current density, and materials and components durability285.

The applications and uses of methanol keep broadening and pushing its industrial demand into a continuous increase286 and making its production from CO2 a powerful alternative to utilize massive volumes of carbon emissions287. However, regardless of the selected technology, green hydrogen should be used for CO2 hydrogenation, to avoid falling into the “hydrogen conundrum”288. For this reason, electrocatalytic processes have been gaining track and include CO2 reduction (e.g., ref. 289), co-electrolysis (to syngas followed by methanol synthesis) and hydrogenation processes129,290,291,292,293.

Methanol uses include purposes as fuel, solvent, reactant, etc.294. Moreover, as a chemical reactant, itself can be considered a building block for materials but also it is an intermediate to produce other building blocks (e.g., olefins, ethanol, acetic acid, etc.) for many other materials. Production of olefins from methanol (MTO process)295 is a mature technology, which could be applied as intermediate step in the vast production of CO2-derived polyolefins. All the technologies for the production of these chemicals, products and materials have been commercially operated and under production, using fossil-based raw materials, for long decades. For these reasons, no further discussion is provided for the materials and processes for their production.

The emerging idea of a Methanol Economy287,296 that centers methanol as the core molecule to drive the production of a variety of fuels, chemicals, products and materials has been on the plate for more than 15 years. Yet, not all technologies have been developed, nor are commercially available297,298, some need improvements299 and many more are commercially mature287. Therefore, the opportunity exists for replacing the conventional energy and carbon intense methanol synthesis, for a decarbonized and decarbonizing process technology based on CO2 and to start implementing the methanol economy. However, very little has been reported on the economic and environmental feasibility of the CO2-based processes. An assessment based on thermodynamic data for the methanol synthesis and considering methanol as energy carrier showed an improved exergetic efficiency of the overall energy conversion-storage system including methanol as storage medium and the exergy of the heat released in the synthesis reactions was between 16.2% and 20.0%, depending on the applied conversion technology255. The electrochemical production of methanol resulted uneconomically expensive (production scenario was Germany). Two factors contribute to the high costs namely, the capture costs and the energy (electricity) costs300. An attempt to compare production costs from different technologies and feedstocks was reported though assessments did not include the capture cost, nor the feedstocks production costs and data corresponded to different geographical locations. All these factors are known to affect the economy of the methanol production from CO2301.

An example to optimize the supply chain, in Germany concluded that optimal CCUS systems achieve economic profits of 999.62-1568.17 euro per ton of CO2 captured and utilized in the production of methanol, dimethyl ether, formic acid, acetic acid, urea, and polypropylene carbonate302. The exothermicity of the synthesis reaction offers an opportunity for energy integration that might lead to economic improvements. A TEA/LCA study was performed on an energy integrated capture-synthesis plant where the heat generated in the thermo-catalytic synthesis of methanol was employed to regenerate the capture solvent. Nearly 33% energy saving was achieved for solvent regeneration though the process resulted economically unfeasible. At an energy cost of 70€/kWh, the cost of production was 1.5 times the evaluated potential revenues279. Another energy integration system regards biomass-fired oxy-combustor and a solid oxide electrochemical electrolyzer. Although energy savings are mentioned, their impact on economy and/or carbon footprint were not evaluated303.

The environmental performance of methanol (and urea) production, from CO2 in blast furnace emissions of a steel mill was evaluated within seven different scenarios, varying energy sources and methanol synthesis capacity. The evaluation considered the whole functional unit (FU) producing both steel and methanol, according to ISO 14044:2006 Standard and resulting different among the seven considered scenarios. Global warming impact (GWI) reductions from 0.70 to 4.62 MtCO2-eq/FU were observed within the seven scenarios98.

Sustainable production of CO2-derived materials

The previous Section (Production Pathways) clearly indicates that CCU process technologies might provide potential benefits either economically, environmentally or both. Most analyses indicate the notably reduction of environmental impacts and of GWP by CCU technologies compared to their conventional counterpart manufacturing processes.

The following paragraphs will consider approaches to attain (environmental, energy, and economic) sustainability in association with giving use to carbon emissions through the pathways of Section 2. The process technologies and material flows discussed in Section 2 create a broad platform for the production of CO2-derived materials, possessing a great potential for becoming sustainable. As mentioned in the Introduction Section, the circular economy (CE) may underpin this potential but circular, per se, does not imply sustainable. The status reached by the numerous process technologies for producing chemicals and materials from CO2 provides a wide platform for formulating a carbon-based CE (CCE). In fact, the considered CO2-derived materials (Fig. 3) not only will consume large amounts of CO2, for their production but also represent long-lasting storing options. The life-span extension of some of the considered materials in this work have been collected by the International Energy Agency, together with the CO2 consumption of their production47, see Table 1.

With the exception of the commodity chemicals (urea and methanol) of massive volumes of consumption (see Production Pathways Section for details on uses and applications), the lifetime of these materials spans over the centuries scale. These long-lasting CO2-derived materials and their production processes discussed above might bear environmental and social sustainability, and in some instances, even energy and economic sustainability has been proven. Nevertheless, further extension of the lifetime of these materials and a larger incorporation of CO2 in their matrix are being pursued while assessing the expected reduction in emissions, as discussed in the Production Pathways Section. For instance, carbonation reduced 0.05 tonCO2/tonsequestered-CO2 at a cost of 14 US$/tonCO2 stored, decreasing capital cost by 20%304.

In the Production Pathways Section, within the LCAs results’ discussion, the environmental impacts of closing loops in service-oriented materials are observed through increases on resource and energy efficiency and emissions reduction. Some of the cited examples include extending lifespans by remanufacturing plastic objects, reuse building material and recycling of decomposition products as raw resource replacement. Clearly, these are a few examples in comparison with the potential opportunities that the manufacture of these long lasting materials can create, for reducing the environmental impact of conventionally manufactured counterparts. There is a high potential to contribute in reaching the Net Zero Goals of 2050 through the massive production of these materials. However, since circularization and sustainability have not been attained for their production, further investment in research is still needed and as mentioned above gaps and challenges to achieve a sustainable circular production of CO2-derived materials should be the focus. The development and implementation of CO2-based industrial chemical processes would be the basis of a decarbonized industrial and manufacturing sectors.

In order to underpin a positive economy, a first step is to start considering CO2 as a commodity and to assign it a market value, as suggested by Styring305. The environment, industry/businesses and society, all together benefit from the economic development brought about by a CE systemic approach. Multi-dimensional CE systems performing under optimized environment quality, human welfare, and pecuniary progress result sustainable. Sustainable circular economy (SCE) systems and their goals are multi-dimensional in nature306. Therefore, the circularization approach of the CCE needs to bear principles, leading towards sustainability. A CE overview provided by Kalmykova et al. detected commonalities and derived the CE underpinning principles23: (i) resource optimization, (ii) waste prevention, (iii) eco-efficiency, (iv) eco-effectiveness. Resource optimization is determined by the recognition that there is not an unlimited source of materials. Meanwhile waste prevention leads to the reduction, reuse, recycle, recover, and repurposing of materials and products. The first and second principles are coupled together into the eco-design principle to encompass a holistic resource and materials management, i.e., optimum use of resources and waste generation avoidance. Eco-efficiency is the minimization of the volume, velocity, and toxicity of materials flowing through the systems, eco-effectiveness concerns a supportive relationship between the transformation of products and their associated material flows with ecological systems and future economic growth. Then, the potentiality of achieving sustainability through the circular integration of the processes brings about the incorporation and application of these three principles (eco-design, eco-efficiency and eco-effectiveness) applied in association to the closure of the carbon cycle. Figure 5 illustrates these principles definitions, in association with a CCE and the sustainability pillars considered in this work. As depicted in Fig. 5, the selected CCU option is key in the achievement of both energy and environmental sustainability.

Sustainability principles in association with a CCE.

The many LCA and TEA studies recommended some typical improvements, including the use of eco-efficiency and eco-effectiveness tools and methods, as well as of renewable energy and materials resources. Regardless of the efforts of the International Organization for Standardization, on LCA protocols307,308, one point of attention comes from the various methodologies being used in these studies that preclude or at least inhibit the comparison of results. Besides the standardization efforts, Zimmermann provides guidelines for both techno-economic and life cycle assessments of CCU technologies, to improve comparability of such studies309. A clear and better documentation, and reporting of the description of the justification and background of the chosen LCA methodological are still missing. Additionally, many CCU technologies have not been evaluated. The LCA results for technologies producing methanol, methane, dimethyl ether (DME) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC), using CO2 as reactant have the potential to reduce environmental impact compared to current practices. However, the purely utilization of CO2 is not a guarantee for environmentally sustainable, LCA is still needed, and its application broadened to the technologies not evaluated yet. Attention should be placed to identify hotspots, guide future research and provide performance targets while assessing environmental impacts of the production processes and of the derived products (e.g., their toxicity and longevity). Another point of attention is the quality of the data and particularly that acquired from low TRL process technologies310. Garcia-Garcia, et al. remarked the potentiality of CCU technologies and made specific recommendations regarding LCA data, methodologies and evaluations310. Meanwhile, Thonemann in a previous review of 52 articles concluded that none of the 44 considered process technologies, for the production of chemicals from CO2, performed better (in each of the analyzed impact categories) than the conventional production alternative311. Clearly, improvements are needed towards standardization, methodologies, data and results reporting, tools, and/or any other aspect that leads to facilitate comparability.

The R&D efforts on the sustainable production of intermediates and final products and materials have been most relevant in the case of polymers, as pointed out in Section 2. The advantages of polymers’ applications (e.g., natural resources protection, safety and energy savings) that led to their massive usage have turned around due to their negative environmental impacts, with consequences on market demands, caused by the social response. Multiple approaches have been considered to address these issues, including research, accelerated development of emerging and new technologies, improvements of existing technologies, circularization, policies and regulatory framework development, etc.235. Some recommendations have been given: use of waste feedstocks (lignin, CO2 and non-edible biomass), environmental materials design, end-of-life separation, reuse and recycling, and applying green chemistry principles to energy and water efficient use239. A significant reduction of GHG emissions has been evaluated when a synergistic use of biomass and CO2 is involved in the polymers production202. An environmental advantage of the CO2-derived, CO2-biomass-derived, biomass-derived polymers and bio- with CO2-derived composites is their biodegradability184,240. However, no LCA has been reported that includes this advantage in the assessment. Instead, studies on the environmental impact of conventionally produced plastics suggest to increase the R&D efforts in biodegradation233. LCAs on general plastics typically conclude on the needs for circularization of the supply chain through reuse, recycling, repurposing, remanufacturing, and the like though the recommendation for the search of alternative functional replacements is also included, e.g.,312. An alternative circularization approach has been proposed to improve the economic and environmental sustainability of (polyurethane and thermoplastics) polymers produced from renewable feedstocks. This circularization approach considers the integration of forming, depolymerizing, and reassembling process technologies313. A TEA/LCA study on the PUs biological and chemical depolymerization was carried out, within the context of this circularization approach. Materials flow was affected by the lower quality of the depolymerization products that required higher amounts of raw materials to compensate any consequence on the physical properties of the final product, which led to higher use of fossil fuels and higher energy consumption. Nevertheless, recycling of the depolymerized intermediates for re-forming the polymer had environmental benefits203, rising circularization promises. In general, polymeric materials offer the broadest possibilities for circularization via Re-X approaches. The development of new sustainable polymers needs to keep in mind the complexity of the Re-X alternatives, from the early design/formulation stage, by a closer following of manufacture to demand requirements and by fulfilling SCCE economic objectives. The Re-X approaches may contribute to overcoming some of the identified challenges: functional stability, recyclability, selectivity in recycling or depolymerization, and the limitations of energy cost. Then, the R&D activities should address new monomers design, polymeric structures, and greener and more energy efficient protocols234.

Regarding the energy pillar (see Fig. 5), electrification is one of the most accepted and approached strategy for industrial decarbonization. The chemical industry, directly concerned in this work is at the top ranking of the hard to decarbonize sectors. Since energy and electricity generation represents about 25% and 20% of global CO2 emissions314, respectively, the latter accounting for the release of over 7700 MtonCO2/y315, the decarbonization of the electricity sector precedes any attempt for implementing an electrification strategy for industrial decarbonization, and so, for the production of sustainable materials from CO2. Regardless of the strategy applied, improvements in energy efficiency and/or lowering energy consumption are required for more sustainable processes. The potential energy savings opportunities for the manufacture of 64 chemicals, in United States was reported by the US Department of Energy88. The study was based on the 2010 installed capacity and reported two energy savings opportunities: (i) current opportunities as the difference between the (2010) typical current energy consumption and potential consumption if the best technologies and practices available worldwide are applied; and (ii) R&D opportunities as the difference between potential consumption if the best technologies and practices available worldwide are applied and the energy consumption if technologies under development worldwide are deployed and applied. The potential energy savings opportunities for some of the intermediates and materials considered in this work were estimated from the data reported in88 and are summarized in Table 2. Out of the 64 considered chemicals, ammonia production was the top ranked on the energy intensity of its production process, as we have stressed in Section 2.2 since the relevance of this product.

As already mentioned in some instances, approaches have been pursued to improve energy usage, by process integration, energy management and energy efficiency improvements. However, optimizing the use of resources per unit energy employed requires careful management of material flow. Thus, carbon management within a circular or closed-loop is vital in preserving nature and the essence of living beings. A CCE would include technologies for carbon capture (CC), utilization (CU) and storage (CS). Although the key role of CCS technologies in climate change mitigation is widely recognized, their economic sustainability is challenging. Nevertheless, carbon conservation also implies the minimization of wastes as the vehicle to accomplish environmental sustainability316. The optimization of resource efficiency across value chains has the objective of a waste-free industry achieved through circularization. This approach expands the sustainability scope to the entire lifecycle of the materials and products317. The CO2-derived materials discussed in this work exhibit lifetime or lifecycle longer than other C-containing products and will retain that carbon in their matrix for long periods of time. Both inorganic and organic materials (carbonates, cement, concrete, bicarbonates, urea, polymers, etc.) perform under long life cycles. Further, polymers could be recycled, reprocessed, remanufactured, increasing the lifetime even more or are biodegradable falling back into a renewable cycle. Therefore, the type of produced material or its application lifecycle determines the time CO2 spends in the product318. Nevertheless, new materials need to be designed and formulated to functionally replace some of the existing fossil-derived counterparts. The new designs should incorporate potential interactions with the environment and facilitate their re-incorporation in the production/manufacturing processes. Meanwhile, the new formulations should resemble better those of the renewable feedstocks (e.g., CO2, biomass), with less hydrogen and more oxygen319.

Regarding completion of the sustainability components, economic factors have to be incorporated. For this purpose, CU could create opportunities for bringing revenues320 through the production of value-added materials, products and services74. Strategies for energy savings and emissions mitigation under a scenario of economic growth were proposed and included footprint minimization and mitigation, integration, incorporation of clean technologies, eco-processing and eco-production, renewable systems, materials and operations management, and waste minimization321. Similarly, renewable and low-C energy generation constitute fundamental pillars for decarbonization. CMEs are intrinsically needed for producing components and building the energy generation infrastructure. The shortest lifetime of a given component determines the technical and/or economic lifecycle of the energy infrastructure, under which circumstances other components or infrastructure with longer residual lifetime will be wasted. The reduction of waste and closing material loops were identified as attention areas322. Management of materials flow and its circularization are the vehicle to zero waste generation but no ambiguity, uncertainties, or misunderstandings may exist among all stakeholders. Minimizing criticality of CMEs requires the application of the eco-effectiveness principle to transition into CE, to upgrade business-centered approaches to sustainability of a systemic transition of global industrial systems15.

A circular integration of process technologies described above for the production of CO2-derived materials has great probabilities of becoming a negative emissions technology (NET) and environmentally sustainable. In fact, it is well recognized that the CE strategies provide mechanisms for reducing societal needs for energy and primary materials to deliver the same level of service, with lower environmental impacts2. For this reason, the search for sustainability have focused on addressing technical/energy and economic challenges: operating costs reduction by resource management and zero waste generation; operating capacity increase; and energy efficiency improvement by reducing heat demand, optimizing heat management systems and integration to power plants323. The incorporation of life cycle criteria into the assessment of techno-economic models (e.g., s life-cycle costing, LCC; 324,325) is probably a move closer towards the economic impact of achieving sustainability, if applied with sensitivity analysis derived from LCA considerations.

The deployment of the SCE within the different manufacturing, industrial and commercial sector passes for the definition and implementation of corresponding business models. Accordingly, circular business models (CBMs) are needed for each particular business to be developed and their sustainability needs to be targeted. As it was the case of process technologies, the circular integration of business models operating in a linear value chain will not necessarily be sustainable. The multi-dimensional nature the systems is the complicating factor that implies careful orchestration of technology, policies, management principles, etc.326. Relevant examples were given for the design of CBMs for the plastic industry, considering resource recovery from nine different plastics327 and for the recycling of durable hydrocarbons328. Regarding carbonation applications, the logistic issues affecting the circularization could be favored from business models based on industrial symbiosis329, to improve operating costs. In this case, all resources originate from different economic sectors and geographical regions, for which strategic partnerships and/or networks among resource providers are needed. Carbonation80,81,82,83 and circularization330,331,332 can benefit the recovery and/or production of CMEs. This case needs of CBMs strengthening materials efficiency and materials management practices, by considering: (i) incorporation of CCUS technologies; (ii) prioritizing energy saving, (iii) closing loops for critical and non-renewable materials, and (iv) investing in resource and energy-efficient processes333. Such CBMs are characterized by: multi-stakeholder and multi-company collaboration; value transfer from economy sphere to human development; and resource efficiency and clean technology by organizational learning and technology transfer334.

The factors affecting the long-term sustainability of CBMs have been the subject of R&D, e.g., the characteristics affecting model design334, the transformation of the industrial systems335, materials efficiency and materials management practices333. The circularization of the business models is an additional step to derisk a CCE, achieving it sustainably requires additional efforts. The market dynamics introduces an additional factor into the CBM design. For instance, the CBM for a plastic industry would be by design, a restorative and regenerative model, wherein its key aims are to eliminate the concept of waste, rebuild natural capital, and resources are used (not consumed) effectively to create economic benefits by producing value-added products237.

The implementation of a CCE relies on the availability of the CCU technologies, whose status currently varies within the whole TRL range. Based on this status and on the supply-demand market dynamics for gasoline, diesel, methanol, dimethyl ether, dimethyl carbonate and succinic acid, it was estimated that the size of the business, by 2050 would consume approximately 350 Mton CO2/y. The relevance of the supply-demand model was to show the non-linearity of the market dynamics and its impact in the decision making and in production management336. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that this estimation was based on a limited number of products and in their individual production, ignoring the production of derived materials as those considered in this work. Contrarily to this line of thoughts, recently a CO2 refinery has been proposed as a vehicle to achieve a sustainable CCE, consuming large volumes of this compound and producing a broad slate of fuels, chemicals and materials337.

Final remarks

The chemical use of CO2 as feedstock to produce valued materials (Fig. 3), such as inorganic carbonates and polymers provides a myriad of opportunities for massive use of CO2 emissions and fixate it in long-lasting materials. CO2 can be used either directly, in its own polymerization as well as in copolymerization with other molecules or indirectly by transforming building blocks obtained from CO2 in previous stages. A variety of materials with versatile properties of interest for both simple and high-tech applications could be obtained.