Perspective of soil carbon sequestration in Chilean volcanic soils

Introduction

Chile spans from 17.5 °S to 56 °S latitude, displaying a diverse range of landscapes and climates. From the coastal ranges to the volcanically active Andes, the region extends from the hyperarid deserts in the north to the rainforest and Patagonian ice fields towards the south. Chile has 11 out of 12 soil orders considered in the USDA Soil Taxonomy1, covering more than 75 million hectares2. Approximately 60% of this area is productive land, with 5.1 million hectares of volcanic soils, which are highly relevant for agricultural production. A significant proportion of volcanic soils are classified as Andisols, many of which contain considerable amounts of active aluminium (Al), iron (Fe), and manganese (Mn) and poorly crystallized minerals, contributing to their high soil organic carbon (SOC) content, low bulk density (<0.9 Mg m−3) and high phosphate retention (>85%)3. Soil organic carbon levels depend primarily on the balance between input and decomposition rates and complex interactions between climatic factors, soil properties, and land use management. Factors controlling SOC include various in situ stabilization mechanisms, which control turnover rates. For volcanic soils, these mechanisms are mainly related to the amount of oxy(hydr)oxide, the formation of organomineral complexes of Al and Fe, allophane, and imogolite, all of which are amorphous minerals4,5. Ligand exchange reactions are typical of Andisol6,7. Aran et al.8 demonstrated that non-allophanic Andisols can immobilize organic C, supporting the idea that amorphous materials such as organomineral complexes of Al and Fe, other than allophane and imogolite, control the stabilization of SOC9. In contrast, non-volcanic soils contain more crystalline minerals, and the content and clay type control the accumulation of SOC in these soils10.

Chilean volcanic soils are rich in organic carbon (up to 18%) with the presence of allophane (2–15%), which makes up approximately 50% of the soil’s clay11. These soils contain important quantities of reactive Al, amorphous iron (Fe), and poorly crystallized minerals and oxides, which contribute to their distinctive properties9. Matus et al.11 validated the hypothesis that extractable Al, rather than the clay content and climatic conditions, as previously demonstrated in New Zealand volcanic soils12, was the most important factor for controlling the SOC content in Chilean volcanic soils. This was achieved by compiling 169 pedons sampled at 20 cm depth in central south of Chile, formerly under the native forest Nothofagus spp., which is currently used as pasture or arable land. Later, Panichini et al.13 supported this hypothesis for Al and Fe bound to SOC from 13 soil profiles.

In contrast to allophanic soils, adsorption and desorption, hydrophobicity, and electrostatic interactions between organic C and clay minerals are the main stabilization mechanisms for non-volcanic soils. Like Matus11 and Panichini13, other researchers have shown under a broad range of climate and geochemical conditions that SOC is controlled by vegetation biodiversity and adsorption capacity for minerals and, secondarily, by precipitation and temperature14.

Chilean researchers have identified 13,612 soil profiles through the CHLSOC database15 based on previously published and unpublished records across the country16. However, from the perspective of C sequestration, these generalized soil inventories are not very informative, particularly for soils with distinct properties such as volcanic soils. Despite their high SOC contents, volcanic soils are highly sensitive to intensive management such as liming for the stable C pools. Forty-three years after the conversion from forest to grassland, management and liming produced a 35% reduction in SOC in Andisol9. The interpretation of these patterns is as follows: (i) The formation of allophane/imogolite occurs at pH values greater than 5–6. Soil pH is controlled by carbonic acids during this process, and (ii) the formation of Al-organomineral complexes occurs below pH 5. Organic acids control the pH during this process due to the high accumulation of SOC (slow decomposition under cooler/wetter conditions and high C input)3,5,9. Thus, intensive management and increased pH, mainly due to liming, cause the alteration or disappearance of andic properties such as Al-organomineral complexes, resulting in the loss of C to the atmosphere after 30 years of management17,18.

However, the formation of Al-organomineral complexes that can sequester more than 50% of the soil SOC in Andisols19,20 is not only the main mechanism of C stabilization. Old volcanic soils located in the Chilean Central Valley, mainly Ultisols formed from highly weathered Pleistocene ash deposits called ‘clayed red soil’, contain more crystalline clay minerals such as kaolinite and halloysite and a minimum amount of organomineral complexes and allophane. The clay content is the major controlling factor for C sequestration in these soils21.

Thus, to better understand the carbon sequestration potential in volcanic soils, it is necessary to identify the main factors controlling organic C in various types of soil of volcanic origin21, which can be compared with that in non-volcanic soils containing more crystalline clay minerals. As Al and soil texture became the main factors for the stabilization of SOC rather than iron22 and climatic conditions11, here, we explored the primary mechanisms of organic C stabilization to predict the potential for carbon sequestration using basic chemical properties such as pH, active Al, (Fe was not measured), and soil texture in a large database of Andisols (n = 396), old volcanic Ultisols (n = 61), and non-volcanic soils (n = 60) with more crystalline clay mineralogy across various land uses in central and south Chile. We hypothesize that soil pH has a stronger impact on Al-organomineral complexes in volcanic soils than that in non-volcanic soils. In contrast, soil texture plays a key role in non-volcanic soils.

Results

Database characterization

In the soils from Databases A–F, the SOC content varied widely, between approximately 1.7% and 41% respectivelly, while the clay fraction ranged between 2 and 59%. The mean pHw was similar between the Andisol (4.0–7.2) and Ultisol (4.8–6.2). The Alp concentrations were measured for the Andisols (databases B, C, D, and F, n = 58) and Ultisols (database C, n = 11), and these values ranged between 0.4 and 1.9%. The Ultisols always had the lowest Alp, approximately four times that of the Andisols (Table 1). In database E, the silt content was measured in 192 Andisols and 15 Ultisols, where Ultisols presented the highest values ranging between 18 and 42%, while Andisols ranged from 2 to 37%. In contrast to the Andisols, the Ultisols presented the greatest amount of clay, with the dominant textural class being clay loam, which is typical of Ultisols or old Chilean red soils. On average, the clay content in the Ultisol was 38 ± 2.9%, while that in the Andisol was 17 ± 1.2%. Therefore, the textural class of the Andisols ranged between loam and silty loam. On the other hand, the average SOC in non-volcanic soils was 0.6 ± 0.3–1.5 ± 0.3% lower than that in their volcanic counterparts, while the pH in the water varied from 5.9 ± 0.1 to 6.5 ± 0.1. On average, the clay content ranged from 5 ± 1% in the Mollisol to 15 ± 5% in the Vertisol. However, the Mollisol had the highest silt content of 22 ± 4% (Table 2).

Relationships among soil properties of volcanic and non-volcanic soils

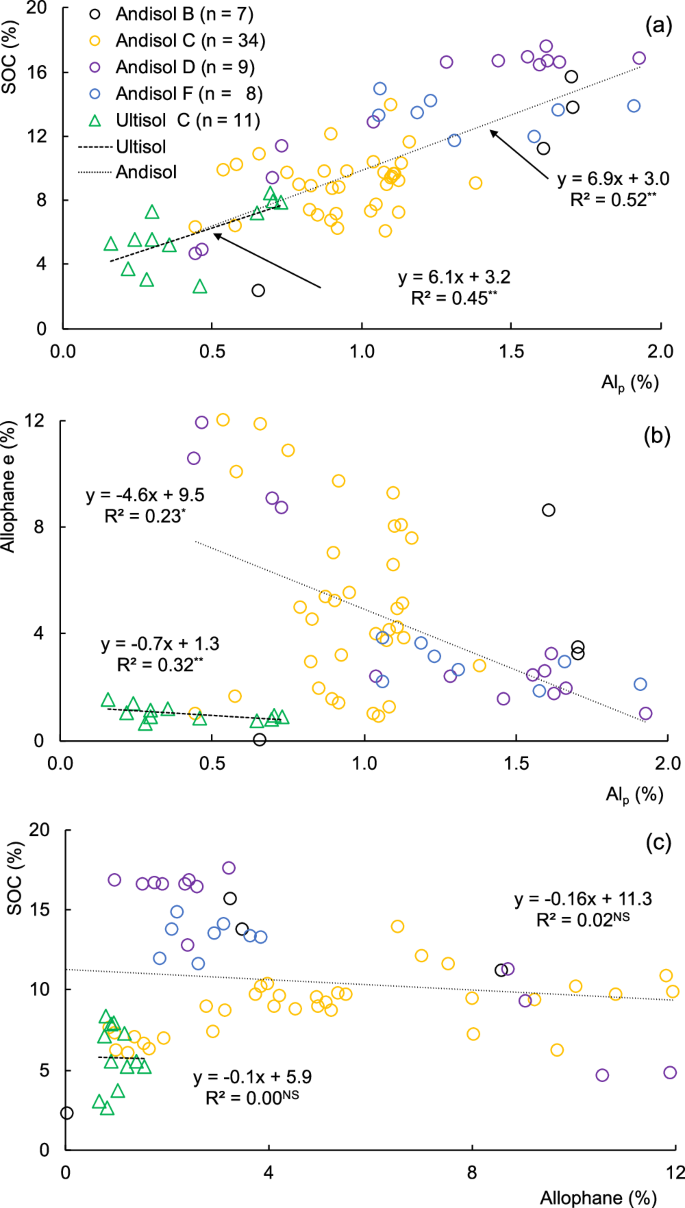

There was a strong and positive relationship (p < 0.01) between the Alp and SOC contents in all databases studied, both for the Ultisols and the Andisols (Fig. 1a). Alp varied between 0.2% and 0.7% in the Ultisol and between 0.4% and 2% in the Andisol, with SOC contents of 0.5–0.8% in the Ultisol and 2–18% in the Andisol. Both regressions explained more than 45% of the SOC variability with similar slopes, i.e., for each unit of Alp increase, the SOC increased by 6.1–6.9%. In contrast, Alp was inversely correlated with the allophane content in the Ultisols and Andisols (Fig. 1b). The allophane content in the Andisol (12%) was eight times greater than that in the Ultisol. However, the slope for the Andiols was steeper than that for the Ultisols, showing the strong influence of Alp on allophane. When allophane was related to SOC, a non-significant negative relationship was observed only for the Andisol, and no relationship was detected for the Untisol (Fig. 1c).

Relationship between organomineral complexes of aluminium extracted from sodium pyrophosphate (Alp) and (a) soil organic carbon (SOC) and (b) allophane, as estimated from Eqs. (1) and (2) (see text), and (c) between allophane and SOC in Andisols and Ultisols. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; NSp > 0.05.

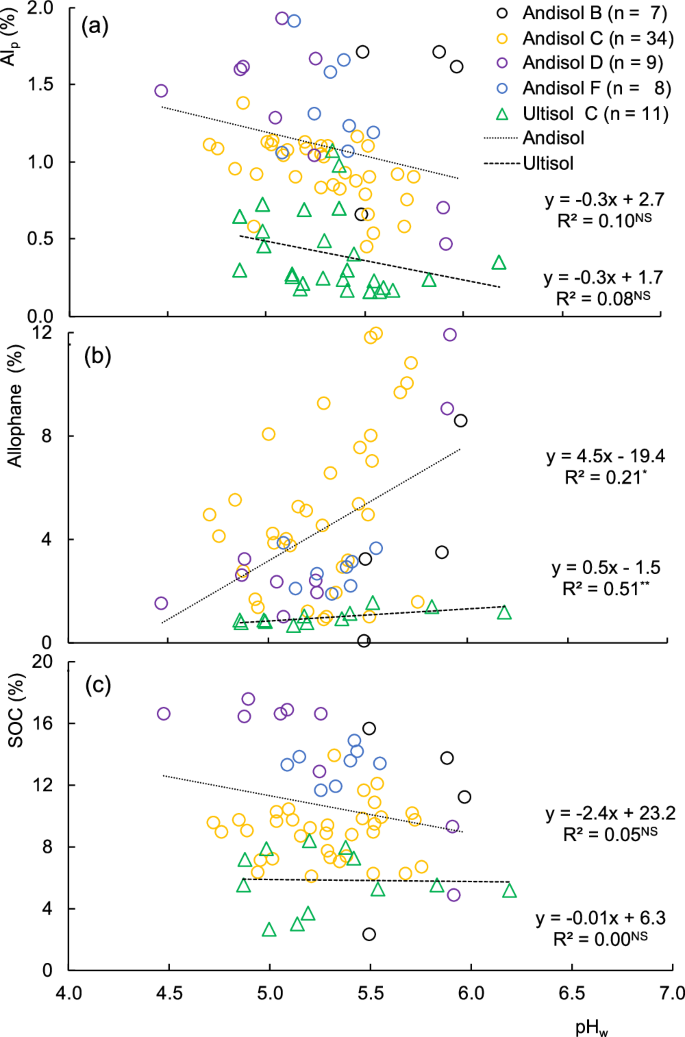

There was a poor but negative relationship between soil pH and Alp in both soils with similar slopes. This means that pH influenced the Alp of both soils in a similar way (Fig. 2a), but not for allophane. In the case of the Andisols, the allophane content increased nine times compared with that of the Ultisols (Fig. 2b). When the soil pH was related to the SOC content, no correlation was found (Fig. 2c).

Relationships between soil pH in water (pHw) and (a) Al-organomineral complexes extracted from sodium pyrophosphate (Alp), (b) allophane, and (c) soil organic carbon (SOC) in Andisols and Ultisols. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; NSp > 0.05.

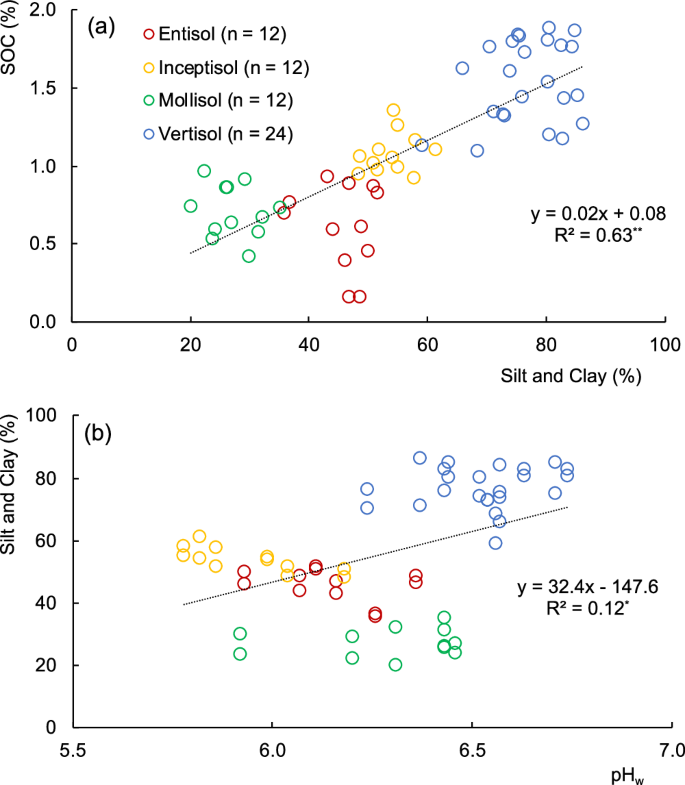

On the other hand, there was a strong and positive relationship (p < 0.01) between the silt and clay contents and SOC. Mollisols had the lowest SOC content, and Vertisols had the highest SOC content, with >66% silt and clay (Fig. 3a). The soil pH was correlated with the silt and clay contents, although this relationship was weak (Fig. 3b).

Relationships between (a) silt and clay particle size and soil organic carbon (SOC) and (b) between pH in water (pHw) and silt and clay particle size in non-volcanic soils. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; NSp > 0.05.

Discussion

There was a positive and highly significant relationship between Alp and SOC (p < 0.01) for Andiols and Ultisols, where the Al extractable by pyrophosphate, the Al-organomineral complex, explained more than 45% of the SOC variation in both soils (Fig. 1a). However, this relationship for allophane content, as estimated by Eqs. (1) and (2), was inversely proportional to Alp, particularly in Andisols, where the slope was more pronounced than that in Ultisols (Fig. 1b). It can be expected that the more Al that is complexed with organic C, the lower the allophane content, similar to what has been called an anti-allophanic effect. The availability of Al3+ is a critical factor that controls Al-organomineral complex formation18. Aluminium polymers can react with silica to form allophane/imogolite when there is an excess of Al relative to the complexing capacity of humic substances3,5. However, we also found that the SOC content remained unchanged despite the variation in the allophane content (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1c). An increase in soil pH due to liming (usual practice in Chile) tends to reduce Alp in both soils (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the allophane content continues to increase (Fig. 2b). The decrease of Alp and allophane increases may help explain why the amount of SOC tends to remain unchanged by soil pH (Fig. 2c). Allophane can bind less SOC than Al-organomineral complexes, the latter making up more than 50% of SOC than other amorphous clay minerals13. Therefore, the formation of allophane and its associated C partly behind “compensate” for the loss of C from the Al-organomineral complexes. This reduces the impact of pH on the SOC (Fig. 2c). These results are consistent with previous ones9 in which SOC losses were estimated to be due to a reduction in organomineral complexes and to an increase in SOC associated with amorphous minerals dominated by short-range-order materials (allophane, imogolite, and ferrihydrite)9. The present results supported the hypothesis of this study since the amount of Al bound to organic C is strongly influenced by pedogenic factors such as pH in volcanic soils. Although allophane was scarce in the Ultisols, a relationship with soil pH could still be observed (Fig. 2b). Compared to Andisols, Ultisols have 2–4 times less Alp (Table 1) due to the presence of more crystalline clay minerals, such as disordered kaolinite and halloysite21.

Interestingly, there was no consistent relationship between silt and clay contents and the SOC content in volcanic soils, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Furthermore, a negative correlation was found, which is in line with previous findings, because an increase in the allophane content, does partly compensate for the total C losses due to the destabilization of Al-organomineral complexes as the pH increases in Andisols9,11. This finding contrasts with the positive and highly significant relationship observed in non-volcanic soils (R2 = 0.63, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3a). However, it should be noted that this relationship was found among soil orders and not within the group, indicating that the amount and clay and their mineralogy of dominant clay played a key role in the accumulation of organic C. The clay content was Vertisol > Inceptisols > Entisols > Mollisols with 15%, 12%, 9%, and 5% of clay, respectively. It should be noted that Vertisols have illite, smectite, and vermiculite and showed the highest SOC contents. In comparison, the Entisols and Mollisols have illite and kaolinite with the lowest SOC contents (Table 2). There was a poor correlation between the pH and silt and clay content of non-volcanic soils (Fig. 3b), and then a poor correlation between pH and SOC (relationship not shown, R2 = 0.22, p < 0.05). This finding supports the second hypothesis of this study, which suggests that soil texture rather than pH affects the level of organic carbon in non-volcanic soils. Therefore, silt and clay particle size cannot be used as reliable indicators to predict organic C levels in volcanic soils, unlike soils with more crystalline clays as in non-volcanic soils.

In line with the previous results, Matus et al.11 reported that SOC levels in regions with latitudes ranging from 38 to 42° S were controlled by the soil Al content rather than by climatic conditions. Similar outcomes were confirmed by Garrido & Matus22 (database C), Panichini et al.13 (database D), and for the expanded B and F databases studied here. We interpret that soil management and pH had destabilization effects on Al-organomineral complexes, leading to the formation of allophane, for example, through land-use change and liming (cf Figs. 1b and 2b). The stability of short-range order minerals23,24,25 is challenged by the mineralization of released organic matter from Al complexed otherwise stabilized, which may cause significant changes in the SOC of allophanic Andisols with small variations in soil pH9.

In conclusion, the increase in soil pH does not result in a faster decrease in SOC as anticipated in volcanic soils. This is due to the distribution of Alp versus allophane and their distinct roles in SOC sequestration. Additionally, the clay content and mineral composition play important roles in stabilizing organic C in non-volcanic soils.

Methods

Chilean volcanic soils

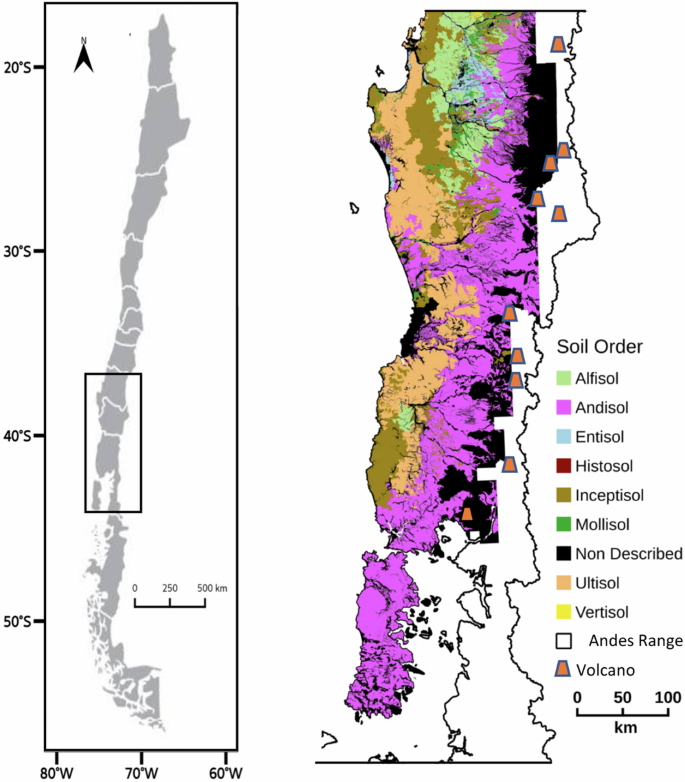

Most volcanic soils in Chile were native Nothofagus spp. forests before slash-and-burn became a common practice to open land for farming during the 19th century. Approximately 5.1 million hectares (60%) of Chilean agricultural land is derived from volcanic materials26. Approximately 80% of these soils are used for small-grain cereal or grass pastures27. Figure 428 shows the soil order distribution in southern Central Chile. The mean annual precipitation varies from 800 to 2750 mm, and the mean annual temperature 11-16 °C between the Coastal and Andes Range in the central southern valley of Chile (Fig. 4). We also sampled soils on the slopes of the Coastal Range and foothills of the Andes Range whose vegetation is native forest (Nothofagus spp.) and pine plantations (Pinus radiata de DON).

Most soils have volcanic influence. Ultisols are locally known as ‘red soils’ (see text) (After Reyes-Rojas et al.28).

A total of 457 soil profiles sampled up to 0–20 or 0–30 cm deep, excluding the organic horizons, were compiled from six databases (A to F). Most of the sampled soils were under grasslands, native forests, and a few croplands, where wetland soils were excluded. The original database published by Matus et al.11 included 146 Andisols and 35 Ultisols (Database A), Crovo et al.29 sampled seven Andisols (Database B), and Garrido & Matud22 34 Andisols and 11 Ultisols (Database C), Panichini et al.13 nine Andisols (Database D), Salazar (data not published) 192 Andisols and 15 Ultisols (Database E), and Zamorano (data not published) eight Andisols (Database F). Soil samples from database B–F were analysed by dry combustion using a TOC instrument (e.g., module TOC-SSM-5000A)-VCSH (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) by 900 °C soil combustion. Inorganic C was analysed in several samples from the same module, TOC-SSM-5000A, after hydrochloric acid addition, and no carbonate was detected. In contrast, Walkey and Black were used for Database A (n = 146). There is good agreement between the Walkley and Black methods and dry combustion for Chilean volcanic soils30. Soil texture was determined by the Bouyoucos or Pipette methods31. The allophane content was determined from the atomic ratio (Alo–Alp)/Sio32,33. Multiplying Sio by a factor given by Parfitt34 allows the estimation of allophanes in a wide range of contents, ranging from as low as 0.5% to 60%34. The average atomic Al:Si ratio of the Andisol in the present study was 2:1; therefore, the factor used was 7.034.

where Alo and Sio are based on the dry mass used for oxalate extraction (%), and Alp is used for pyrophosphate extraction (%). For additional details on vegetation, clay type, and physical properties such as bulk density, refer to the original publications and literature herein. For comparison, we included 60 non-volcanic samples from soils classified as Entisol, Inceptisol, Mollisol, and Vertisol35 (Table 2). The soil organic carbon in these samples was determined by Walkley and Black. As in volcanic soils, several studies have addressed the uncertainties of SOC determination by wet or dry combustion. However, no significant differences were found (e.g., Matus et al.30 and Olayinka et al.36). Furthermore, none of these soils were detected at 0.14 ± 0.06%, the limit of quantification (LOQ), which is the lowest organic C concentration that can be measured (detected) with statistical significance following the Walkley and Black method37.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained for Alp, SOC, clay content, silt content, and pH. The entire database’s mean, standard deviation, median, range, and quartiles are shown. Normality for different soil orders (volcanic and non-volcanic) was evaluated using the Shapiro‒Wilk test (p > 0.05). Because they did not follow this distribution, the values were log10 transformed. Correlation among soil variables analysed were conducted. All analyses were performed using SPSS v23.0.0.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Responses