Engineering advanced cellulosics for enhanced triboelectric performance using biomanufactured proteins

Introduction

Renewable biopolymers, such as polysaccharides1 and structural proteins2 are composed of fundamental building blocks, including glycans and amino acids. Many industries highly demand renewable materials to support their undertakings of providing unique solutions to sustainability-related problems. Among all these biopolymers, cellulose is the cheapest and most abundant in Nature3. Traditionally, cellulose has been used as an energy source through direct combustion or utilized by the pulp and paper industry (for example, in wood). Recently, cellulose has seen a new chemical transformation into molecular compounds like fatty acids or sugars, which results in low molecular weight chemicals with low commercial value4. Continuous efforts to improve production and use can further enhance its sustainability credentials. Advanced cellulosic materials are rapidly evolving to create unique properties such as cellulose nanocrystals with remarkable strength and transparency, and cellulose nanofibrils with high flexibility and biodegradability5,6. As a sustainable material, cellulose has been used in food packaging, clothing, as well as medical applications.

In Nature, proteins have evolved to interact with cellulosic fibers (e.g., cellulose binding domains7) to enhance their physical and chemical properties. A new paradigm to engineer protein-cellulose interactions lies in the fundamentals of synthetic biology7. Breakthrough technologies for creating bio-engineered materials could be achieved if animal (e.g., silk, wool)8,9,10 and plant (e.g., soybean, zein) proteins are modified to interact with cellulose to achieve renewable alternatives to synthetic polymers. Bioengineering enables us to precisely tailor the amino acid sequences and chain lengths of protein molecules to impart desired functionality, while ensuring compatibility with the disparate biopolymers. Protein-functionalization can be attained in cellulose fibers without any compromise with fiber properties. Moreover, biomanufacturing is an essential technology which has the potential to relieve the burden for sustainable raw material production.

Electrostatic charges are generated when two dissimilar materials are rubbed against each other, a well-known physical process known as the triboelectric effect11. Depending on their intrinsic nature, materials can either accept or donate electrons, and the propensity for electron transfer decides their positions in the triboelectric series12. This phenomenon is essential in solving problems in the design of industrial processes, separating materials in the recycling industry, and operating copiers and printers. Triboelectric devices utilize electrostatic interactions to generate the low power required for the functioning of electronic components. These interactions provide an efficient way to power small instruments without requiring external batteries. Polysaccharides and polypeptides can demonstrate a triboelectric response based on the polar hydroxyl groups of glycans or charged amino acids like histidine, aspartic acid, arginine, lysine, and glutamic acid13.

Numerous materials and techniques (e.g., electrospinning, co-axial spinning, etc.) have been employed to produce triboelectric fibers14. Most commonly, the materials include synthetic polymers like nylon and teflon, natural polysaccharides like cellulose, and proteins like wool and silk. The choice of material for the triboelectric fiber depends on the intended properties, such as its flexibility, output voltage, and current15. As synthetic polymers have sustainability issues and natural resources are limited, there is a need for an alternative triboelectric material16. The biomanufactured proteins possess various advantages over their synthetic and natural counterparts. They provide greater control over the production process, offer the potential for modification of physical properties such as flexibility and triboelectricity, and exhibit biodegradability as a sustainable alternative.

Here, we designed and engineered squid ring teeth (SRT) proteins with cellulose to generate an enhanced triboelectric fiber material. Our prior expertize working with recombinant SRT-based proteins17, where we discovered up to 0.4 nC cm-2 surface charge, motivated our focus on exploring their potential for novel triboelectric properties. SRT has been studied as an intriguing biomimetic source due to the unique hierarchical protein structure, which imparts high strength that allows gripping of prey firmly18. Furthermore, functional fibers and films from SRT proteins have applications in many areas of engineered materials, including soft photonics and advanced materials. For example, SRT has a β-sheet architecture that provides tunable properties such as extensibility19, biocompatibility20, switchable thermal conductivity21, optical transparency22, and self-healing abilities23.

Results

Fiber spinning

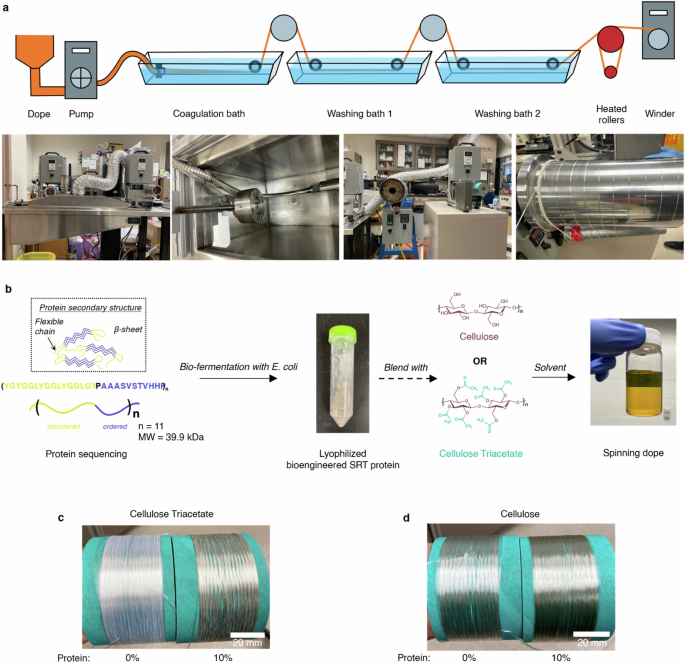

Cellulose and cellulose esters are commonly used as raw materials in solution-spinning processes. In cellulose triacetate, the three hydroxyl groups of cellulose are chemically substituted with acetates. One notable characteristic of cellulose esters is their reduced hydrogen-bonding capability due to the absence of hydroxyl groups. Hence, hydrogen-bond rich and deficient chemistries cover the extremes for a holistic discussion of cellulosic fiber properties. During dope preparation, we noticed that the cellulose and protein solutions were well blended without any visible separation (a representative solution is shown in Fig. 1). To achieve high-strength fibers, the dope solid content was maximized to 13% and 16% w/v for triacetate and cellulose, respectively24. We produced two types of advanced cellulosic fibers. The first type is a blend of triacetate and cellulose fibers containing up to 10% wt of protein. The second type is made by coating proteins onto cellulosic fibers to create bi-composite fibers.

a The spinning setup consists of a coagulation and two washing baths containing DI water. The fibers were dried and heat-set on the heating roller before winding. b SRT protein gene analysis followed by protein gene expression in E. Coli., and protein production using a 100 L bioreactor. The biomanufactured SRT protein was blended with cellulose or cellulose triacetate to prepare the spinning dope for fiber production. Images show bobbins with (c) cellulose triacetate and (d) cellulose-protein blend fibers with 0% and 10% protein content. Fibers with higher protein content appear slightly darker in color.

Bioengineered SRT protein synthesis

Inspired by SRT, a segmented copolymer protein was designed using the amino acid sequence of crystal-forming (AAASVSTVHHP) and amorphous (YGYGGLYGGLYGGLGYGP) sections. The alanine-rich segments undergo β-sheet formation while the glycine-rich elements interconnect these nanocrystals, forming the protein matrix’s flexible regions25. The protein was manufactured in E. coli BL-21 strain using a 100 L fermenter through heterologous expression, as shown in Fig. 1b. Bioengineered SRT proteins have tunable chain lengths. As shown previously, the elastic modulus and the yield strength of these samples are similar; but their toughness and extensibility (i.e., 2%, 4.5%, and 15% for n = 4, 7, and 11, respectively, where ‘n’ denotes the repeat number) increase as a function of polypeptide molecular weight18. We selected the protein variant with the highest toughness and extensibility i.e., n = 11 repeating units (molecular weight = 39.9 kDa). The protein was dissolved with cellulosic biopolymers in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate (EmimAc)/dimethylsufoxide (DMSO) solvent to prepare the spinning dope for fiber spinning.

Since melts of biopolymers is challenging to obtain, we utilized solution spinning (or wet spinning) technique to prepare the fibers. Cellulose and protein solutions are extruded through an array of micrometer-sized spinnerets, and the resulting jets are coagulated in water, an anti-solvent. The formed fibers are stretched (or drawn), washed, and heat-set before winding. The schematic in Fig. 1a illustrates the solution spinning process. Compared to the syringe pump solution spinning approach, our pilot-scale spinning line (see Supplementary Information for real-time fiber spinning demonstration) produces continuous filaments with consistent characteristics (see Fig. 1c, d for images) at 35 g/h fiber production rate.

Structural and mechanical characterization of fibers

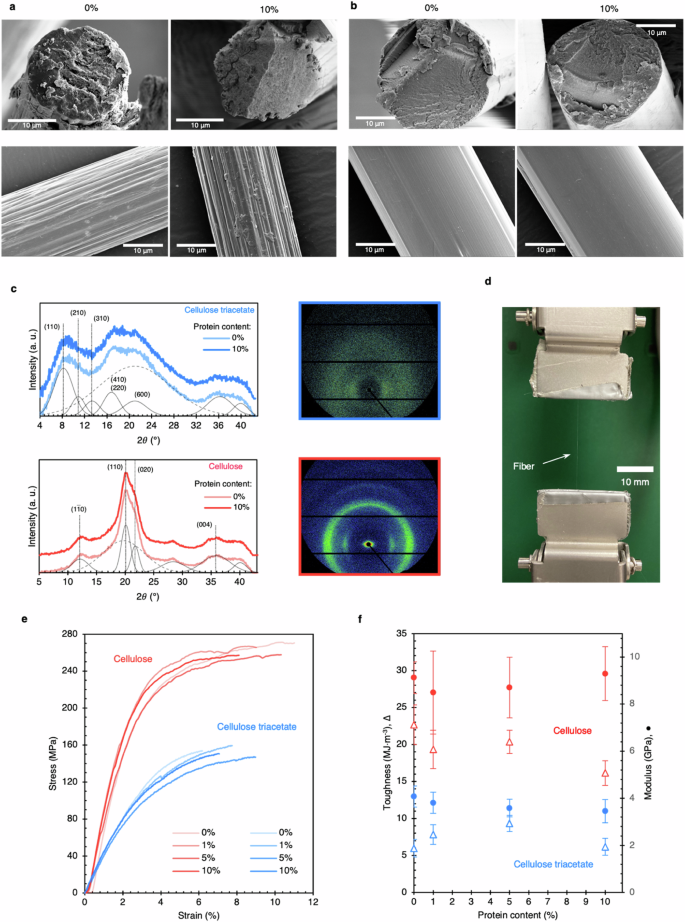

We studied fibers’ structural morphology, and mechanical properties using diffraction techniques, and tensile tests following ASTM standards. Figure 2a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 1 show the scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrographs of the fiber cross-sections and lateral surfaces. The diameter of the drawn cellulose triacetate fibers was 21.5 ± 1.2 μm, while the cellulose fibers had a diameter of 28.6 ± 0.6 μm. Based on the diameter of the as-spun cellulose fibers (56.3 ± 1.6 μm), a draw ratio of 2.6 and 2.0 was calculated for the two types of fibers, respectively (refer to Supplementary Fig. 2).

SEM micrographs of cellulose triacetate (a), and cellulose fibers (b) with 0% and 10% protein content. Cellulose fibers have circular cross-sections and a compact microstructure as compared to triacetate fibers which contain nanopores. The lateral surface of cellulose fibers is smooth. For 1% and 5% fibers, see Supplementary information. c WAXS patterns indicate the anisotropic morphology of fibers. The intensity of cellulose peaks is high, indicating greater crystallinity. Protein peaks were not noticed. The deconvoluted crystalline and amorphous peaks are represented in solid and dashed gray lines, resp. d Optical image of the mechanical stage for mono-filament testing. e Representative stress-strain curves for fibers. Cellulose fibers are higher in strength and stiffness than cellulose triacetate. f The blending with protein did not significantly affect the fibers’ mechanical properties as validated through toughness, stiffness, and max stress.

The wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) patterns indicate anisotropic fiber morphology (Fig. 2c), which is expected for drawn fibers. Drawing also induces constituent fibrils to align along the fiber axis, which contributes to fiber strength26. Cellulose and cellulose triacetate exhibit various allomorphs, among which cellulose-II has been identified for our fibers27,28. The cellulose peaks (2θ = 12°, 20.1°, 21.5°) were more pronounced than those of triacetate, indicating greater amorphous content in triacetate fibers. The crystallinity of cellulose fibers was estimated to be 56.4%, compared to 44.2% for triacetate. Cellulose triacetate has a low degree of crystallization because of the bulky acetate groups on each monomer and increased inter-chain separation. WAXS patterns of pure cellulose and protein blend fibers are very similar, confirming that the protein does not disturb the anisotropy or fibrillar morphology of fibers. The fibers made from regenerated cellulose have a complicated and hierarchical arrangement. This arrangement includes basic units called fibrils, which consist of both crystalline and amorphous segments with small spaces between them. According to Zahra. et al.29, the structure and organization of these cellulose fibrils mixed with 10% keratin remain unchanged, indicating that the hierarchical structure is still present within the network. Kammiovirta et al. showed that keratin can be evenly dispersed in cellulose fibers at low concentrations8. At higher concentrations (at 10.3%), Zahra et al. reported existence of phase-separated keratin domains observable in SEM images of fiber cross-sections29. SEM micrographs of our fibers (as spun or drawn) do not reveal any inhomogeneity or protein aggregation at the same concentration. Moreover, SRT protein – which has a strong WAXS signature18,19 – does not contribute noticeably to WAXS spectra of the fibers. Hence, it can be inferred that SRT remains uniformly dispersed within the cellulose matrix and does not aggregate.

The representative tensile test curves of fibers are shown in Fig. 2e. The cellulose blend fibers show higher breaking strength (256.1 ± 2.1 – 265.8 ± 3.9 MPa)—which is at par with other reports with similar spinning conditions24,30—than cellulose triacetate (136.5 ± 12.1 – 152.8 ± 6.8 MPa). In addition, cellulose fibers are ~2.4 times stiffer than triacetate fibers (see Fig. 2f). Cellulose fibers exhibit superior properties due to inter- and intra-molecular hydrogen bonding, higher dope solid content, and fibrillation. Since SRT proteins only make up 10% of the blend fibers, their mechanical properties do not significantly affect the overall mechanical properties of the blend. As a result, the properties of both cellulose and cellulose triacetate fibers remain unchanged.

Protein conformation in fibers

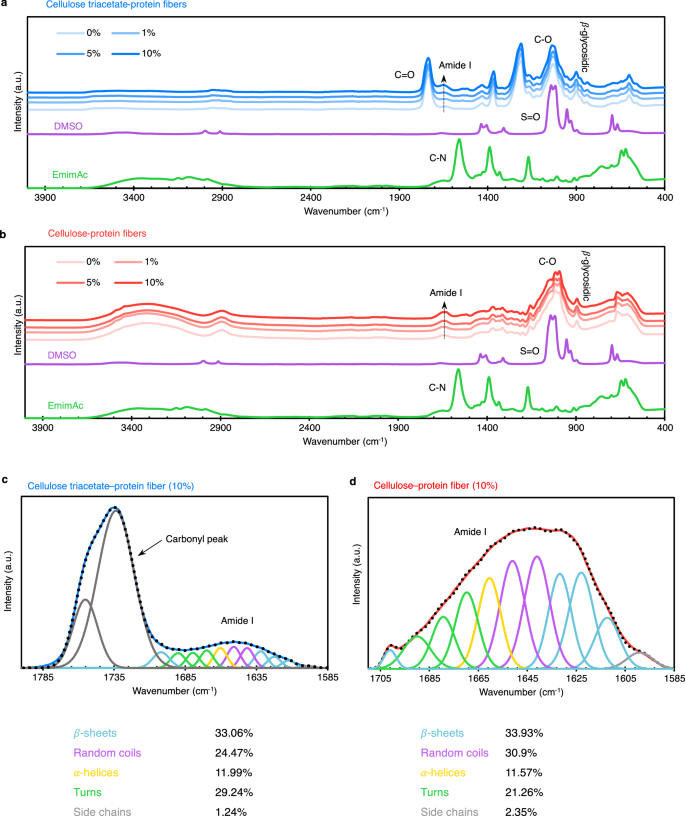

Proteins have been widely studied through Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for the conformational information encoded in the Amide I band. Amide I band upon deconvolution reveals the relative presence of conformations namely, β-sheets, alpha helices, random coils, etc. Our previous studies have shown a semi-ordered morphology for bioengineered SRT proteins, wherein the β-sheet fraction (crystallinity percentage) can reach as high as 55%19, depending upon the conditions around the protein matrix. In this study, we employ FTIR deconvolution to understand the influence of cellulosic biopolymers on protein conformation. Figure 3 depicts the FTIR spectra of the fibers and deconvoluted data for 10% protein fibers. The β-glycosidic linkages (895 cm-1) and carbonyl (1730 cm-1) bands of the FTIR spectra confirmed the cellulose and cellulose triacetate composition of the fibers, respectively (Fig. 3a and b).

FTIR spectra of cellulose triacetate (a) and cellulose (b) fibers show increasing protein content with dope solid fraction. Also, solvents were confirmed to be extracted out of fibers. FTIR deconvolution of Amide I bands of 10% protein fibers was done to quantify protein structures (c, d). The fractions of different secondary structures are tabulated. A significant fraction of the protein is in random coil and helix morphology. The error of fit for the peak at ≈1701 cm-1 for triacetate is greater due to the overlapping carbonyl peak, which is likely resulting in overestimation of β-sheet content.

The rise in the intensity of Amide I and II bands confirms that the protein is retained inside the fibers as its fraction in dope solid increases. This supports our observation that the protein does not leach out in the baths, which can be a challenge with other proteins8,10,29,31, during the entire spinning process (i.e., no turbidity was observed in the coagulation and washing baths). FTIR deconvolution (Fig. 3c, d) showed that SRT, when mixed with cellulosic biopolymers, has a notable presence of random coil and α-helix structures. Also, the β-sheets are present at significantly lower fractions (than the high ≈55% in native hydrated state19), suggesting that the protein chain folding is hindered by the cellulosic chains, most likely due to hydrogen-bond interactions and entanglements. We also produced moisture-corrected deconvolution results (Supplementary Fig. 3) that do not deviate significantly. Hence, without crystalline peaks in the WAXS patterns, FTIR results show that bioengineered proteins are compatible with cellulose, resulting in effective dispersion and no aggregation within the fiber matrix. As discussed previously, introducing proteins does not degrade fibers’ mechanical properties due to this compatibility, allowing for large-scale production and functionalization.

Triboelectric properties of fibers

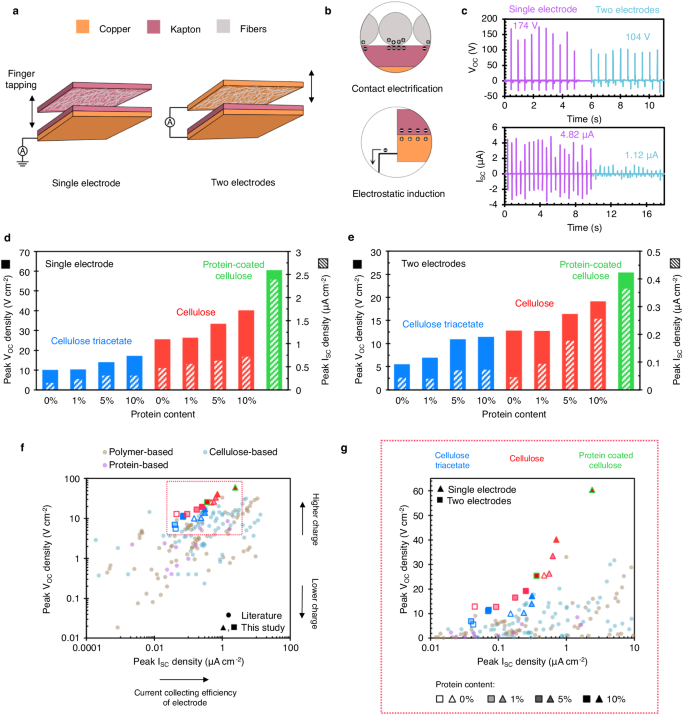

We performed electrical measurements to quantify the charge generation in fibers and the effect of the protein thereof through self-made nanogenerators (see Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4 for schematics). These devices allow us to examine how alternating potentials and currents are generated through contact electrification and electrostatic induction32,33, as shown in Fig. 4b. There are reports on devices with single- and two-electrode configurations. For a holistic discussion and comparison with literature, we conducted experiments in both these configurations. This setup imitates the charge generation process of energy harvesters, most commonly integrated in smart textiles. To avoid piling up of fibers in electrodes, the tests were conducted in contact mode.

a Schematic showing the construction of fiber-based nanogenerators. The top layer containing fibers is finger-tapped with a nominal force (see Supplementary Information for the real time triboelectric output). b The mechanisms of contact electrification and electrostatic induction. c As recorded, triboelectric outputs for the bioengineered SRT protein film, with maximum values noted. The peak open-circuit voltage and short-circuit current densities are shown for both single (d) and two-electrode (e) configurations. Cellulose fibers outperformed triacetate fibers. Protein functionalization further increased the electrical output for both material types. f, g The figure of merit for triboelectric properties: Peak voltage and current densities in various fiber-based materials. The results are segregated into categories, namely, polymer, cellulose, and protein-based materials.

Figure 4c shows the current and voltage measurements as a function of mechanical motion in time for the protein film. The maximum recorded electrical outputs for protein films in the single and two-electrode configurations were 174 V and 4.82 µA, and 104 V and 1.12 µA, respectively. Figure 4d, e illustrate peak voltage and current densities of blend fibers (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for raw signal). Cellulose fibers consistently outperform cellulose triacetate in terms of peak voltage and current densities. While both cellulosic materials are tribologically positive34, cellulose triacetate show a higher electron affinity than cellulose (see Supplementary Fig. 6 for the triboelectric series) and hence, lower electric output. More importantly, blending with protein significantly improved the triboelectric performance of both fibers. Triacetate and cellulose fibers showed a 72% – 108% and 49% – 57% increase in voltage when a protein content of 10% wt was added, as shown in Fig. 4d, e. We posit that the triboelectric strength of the protein is higher due to the presence of charged amino acids (e.g., histidine). Crystallinity and chain packing have been postulated to improve triboelectric output as well35,36,37. The current increases with more charges, indicating that protein has higher triboelectric strength than cellulose, inflating the electronegativity differences between the counter-layer materials.

Blending the protein with cellulose is ideal for a sustainable economy since it directly favors large-scale production of smart textiles from functional fibers through conventional technologies. It also helps introduce higher-quality bio-manufactured materials in fibers, reducing the burden on cellulose industries. However, functional proteinaceous coatings are equally impactful since they can impart sustainability to conventional low-cost materials, while we transition away from a synthetic polymer- to a complete biopolymer-economy. Contemporary studies report the use of inorganics, metals, and polymeric compounds (see Supplementary information for details). We demonstrate the electrical properties of protein-coated cellulose fibers (Fig. 4d, e). These fibers outperform all other fibers (60.48 V cm-2 and 25.38 V cm-2 in single and two-electrode modes) since the protein is concentrated on fiber surface (see Supplementary Fig. 7 for SEM images), primarily reflecting the protein’s properties. It is to be noted that SRT proteins show strong adhesion behavior23 and can even self-heal clothes38. Therefore, SRT protein coatings are durable for long-term use.

Figure 4f compares the peak voltage and current densities of our fiber-based devices with those reports in literature (see Supplementary Table 1 for references). The devices are segregated into categories, namely, polymer, cellulose, and protein based. In single electrode mode, our cellulose-protein blend fibers surpass all other materials with a voltage density of 40.19 V cm-2. The voltage of cellulose fibers can be increased to 60.48 V cm-2 by coating them with our protein, about twice the highest reported (Fig. 4g). Other proteinaceous fibrous-material devices such as silk, chitosan, and wool are not as effective as their voltage densities lie under 9 V cm-2. Since voltage is a better indicator for charge-generation, we ascertain that cellulose-SRT protein blend fibers exhibit the highest charge accumulation among all sustainable triboelectric materials discussed.

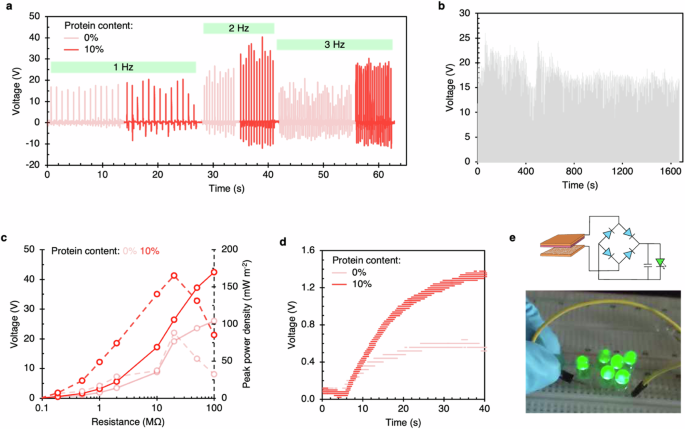

The single-electrode mode shows greater voltage and current output than the two-electrode mode (Fig. 4). This is attributed to the likely charge leakage at the ground; however, more studies are needed to establish the reason. The presence of another electrode offers a better reference for electric potential, i.e., in the two-electrode mode. We performed further experiments with the superior cellulose blend fiber with 10% protein in two-electrode mode to quantify conventional properties like durability, power density, and capacitance. Figure 5 depicts the results in comparison to pure cellulosic fiber. The voltage output reaches a maximum at 2 Hz frequency before dropping at 3 Hz (see Fig. 5a). The voltage output of 10% protein fibers remained higher than pure cellulose. The fibers performed consistently through 2000 cycles of operation (Fig. 5b). The protein fibers reached a peak voltage of 42.4 V at 100 MΩ, about 63% greater than pure cellulose. Also, the peak power density of protein fibers was 87% greater than pure cellulose (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, the protein fibers charged a 0.1 μF capacitor faster to a max voltage of ≈1.3 V, compared to ≈0.6 V with pure cellulose (Fig. 5d). Lastly, we constructed a low-power electronic circuit with the protein fibers to demonstrate the illumination of LEDs (see Fig. 5e for the image).

a Voltage output vs. tapping frequency for 0% and 10% protein fibers. b Durability test of 10% protein fiber for 2000 cycles. c Peak power density and voltage vs. resistance for 0% and 10% protein fibers. d A 0.1 μF capacitor was charged using the fiber devices showing fast and greater charging with 10% protein fiber. e Low-power electronic circuit powered using 10% protein fibers.

Beyond smart textiles and energy harvesters, our triboelectric biopolymer fibers could be beneficial for filtration. Some reports discuss nanogenerators as power sources, while others use the fibrous media directly as respirators39,40. He et al. have reported a triboelectric respirator designed to control humidity within, with a filtration efficiency of 98.83%41. Other studies demonstrate a respirator with a dedicated self-charging design to prolong effectiveness40,42. Moreover, triboelectric filtration systems and respirators have been introduced commercially, as reported by Liu et al.39. The flexibility of our spinning method is showcased by producing finer and more delicate fibers (Supplementary Fig. 8). It has been demonstrated in literature that finer fibers exhibit greater triboelectric charge generation due to higher specific surface area43. Moreover, filtration efficiency increases significantly with the reduction in fiber diameter44.

Biodegradation and circularity

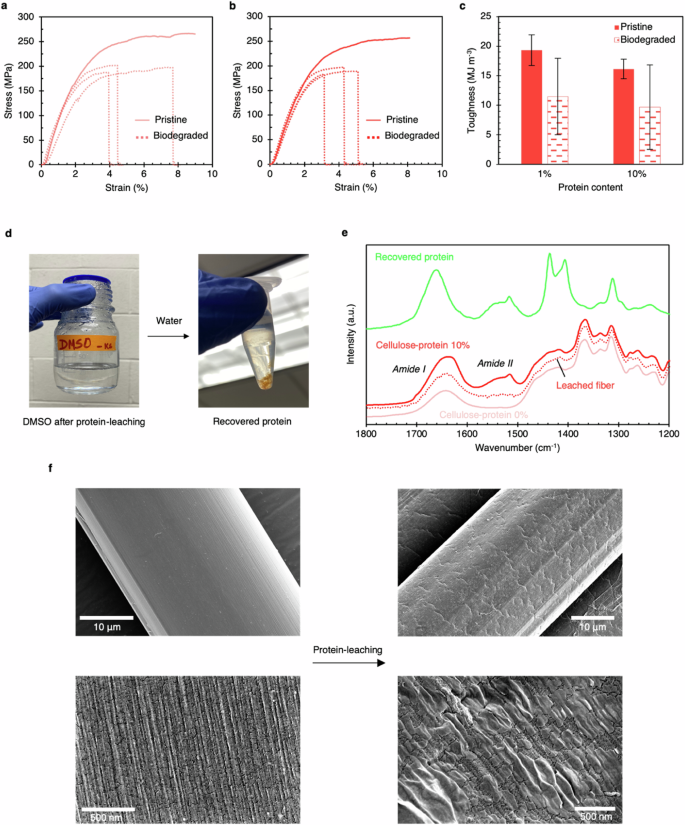

Textile disposal can lead to micro-plastic pollution and finding ways to biodegrade fibers easily is important. We conducted biodegradation of cellulose fibers (0% to 10% protein content) in a domestic waste composter with food waste. Figure 6a, b depict representative tensile test curves for the 1% and 10% protein fibers after biodegradation. Samples fit for mechanical testing could not be obtained for other fiber types. Upon biodegradation, up to 27% reduction in strength and 60% reduction in toughness was observed (Fig. 6c). This shows cellulose-protein fibers can be readily biodegraded under domestic conditions.

Representative tensile test curves are shown for pristine and biodegraded cellulose fibers with 1% (a) and 10% (b) protein content. After biodegradation, the fibers show lower strength and elongation. c Comparison chart of toughness of pristine and biodegraded fibers. d The protein dissolved in DMSO after leaching out of the fibers can be precipitated out using water. e Amide I and II bands of the FTIR spectra of the recovered residue confirms it being the protein. Amide bands are eliminated from the spectra of the leached fiber. f SEM micrographs showing the change in fiber microstructure after DMSO treatment. The diameter of the fibers increased by about 2 μm, indicating increased porosity.

We conducted experiments to demonstrate the ability to recycle protein found in cellulose fibers. Using DMSO solvent as a proof of concept, we performed leaching experiments (Fig. 6d) and found that SRT proteins dissolve well in DMSO, while cellulose only swells and does not dissolve in this organic solvent. We confirmed the protein chemistry through FTIR and observed that the contour of the Amide I and II regions in the FTIR spectra of protein-leached fiber matches that of pure cellulose fiber, confirming complete protein extraction (Fig. 6e). DMSO-treated fibers show reduced Amide I and II band intensities, whereas intense Amide I and II regions are present in the protein spectra. We also observed morphological changes in the fibers during the treatment, as shown in Fig. 6f, where coalescence of surface regions was observed in optical images. We suggest that the swelling of cellulose in DMSO and water caused the coalescence of projected parts during drying. An increase in porosity of ~10% was observed due to a 2 μm increase in fiber diameter. These morphological changes expand the potential applications45,46,47 of these fibers.

Discussion

We have created advanced cellulosic fibers using biomanufactured proteins, resulting in recyclable and biodegradable materials. By adding protein, we increased the voltage output of cellulosic fibers by 49%–108% at 10% weight, as well as increased peak power density and capacitor charging for triboelectric applications. The cellulose-protein blend fibers are high strength (over 250 MPa), enhanced toughness (around 30 MJ m-3), and stiff (about 9 GPa). We have demonstrated the value of bioengineering by designing functional proteins that can be integrated with traditional biopolymers for a synergistic effect. Our study shows the potential of biomanufacturing to reduce waste by incorporating biodegradable and recyclable materials into products, leading us toward a more sustainable future.

Methods

Materials

Extra pure microcrystalline cellulose (average particle size 90 μm, Acros Organics, code: 382312500) and cellulose triacetate (Acros Organics, code: 177822500) were used as received from ThermoScientific Chemicals. 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate (EmimAc), with >95% purity (code: IL-0189-TG-1000, water content < 1%), was purchased from Iolitec Inc., and Oakwood Chemical provided dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99.9%, code: 046777).

Bioengineered SRT protein synthesis

The proteins were engineered using protein expression, gene sequencing, and protein design according to a previously described protocol18. The DNA sequences were verified in plasmids and then transferred to E. coli (BL21 strain with pet14b plasmid). After colony inoculation and fermentation, cells were collected and grown based on the earlier protocols18. Finally, the fermentation biomass is processed to acquire purified proteins.

Solution spinning

The wet spinning process was continuous, resulting in filaments without breakages. Fibers were produced using a laboratory-scale line (Alex James & Associates Inc.) with components shown in Fig. 1b. Experimental methods like syringe-wet spinning do not accurately represent traditional solution spinning, as the fiber properties vary throughout their length. Short, thick fibers cannot represent textile fibers’ mechanical properties48. Cellulose and cellulose triacetate solutions were spun with SRT protein at weight fractions of 0%, 1%, 5%, and 10% with respect to cellulose/triacetate. EmimAc and DMSO mixture, as the dope solvent, was prepared at room temperature at a 1:1 ratio. The dope solid fraction of cellulose and triacetate solutions was 16% and 13% w/v, respectively. Biopolymers (in powder form) were mixed with the dope solvent, and homogeneous solutions were obtained after stirring for 3 h at 65 °C. High temperatures (over 90 °C) were avoided at all stages of spinning to prevent biopolymer degradation49. A spinneret made of stainless steel with 100 orifices, each with a diameter of 100 µm, was utilized. The pump was maintained at a temperature range of 65 °C – 80 °C, and its speed was adjusted (to flow rate = 4.2 cc/min) to ensure the velocity of the extruded fibers was between 5 m/min – 6 m/min. Fibers were extruded in a coagulation bath of DI water at room temperature, followed by two washing baths maintained at 75 °C and 60 °C, respectively. The fibers were dried and annealed on a heated roller at 85 °C. Co-solvents such as DMSO and EmimAc are known to have the ability to increase the concentration of solutions while simultaneously decreasing their viscosity50.

Protein coated fibers

About 120 mg of pure cellulose fibers were kept immersed in SRT protein solution in DMSO (conc. 20 mg/ml) at room temperature for 2 h. The fibers were removed from the solution and the solvent was dried. The fibers were washed in ultrapure water (at 60 °C) and transferred to desiccator for drying.

Characterization of triboelectric properties of protein film and fibers

Each multifilament was cut into staple fibers and deposited onto Kapton tapes (CGS, 0.0635 mm thickness) of 2 × 1.2 cm2. The apparent surface areas of the fibers in all devices are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The protein thin film was deposited onto a 3 × 3 cm2 Cu sheet using a 500 µl solution containing 10% w/v protein in HFIP solution. Once the film was formed, it was rinsed with ultrapure water and left to dry in the ambient air. Kapton films were attached to copper sheets to create the bottom layers for triboelectric measurements, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Polyethylene foam sheets, which were 0.5 cm thick, were used as insulation between the upper and lower layers. The voltage and current were measured using Siglent SDS 1104X-E oscilloscope and MetroOhm Autolab Pgstat128n Potentiostat, respectively. The experiment involved tapping fingers at a frequency of 2 Hz while referencing a metronome. The detailed mechanism of functioning of single and two-electrode triboelectric measurements is discussed elsewhere51. The frequency test was done with tapping rates of 1 Hz, 2 Hz, and 3 Hz. The durability test was done for 2000 cycles using an automated setup at 1.25 Hz tapping rate. For capacitance test, a 0.1 μF capacitor was charged through a full-bridge rectifier at a tapping rate of 3 Hz. A low-power circuit was constructed using a full-bridge rectifier and several LEDs.

Figure of merit for triboelectric measurements

This plot shows the electrical output of various materials and structural parameters. As the counter layer area increases, charge transfer and electrical output increase. In addition, fibers have a larger surface area and facilitate electric charge transfer compared to films. It is essential to exclude the geometric influence on the output of devices when comparing materials based on their intrinsic triboelectric performance. We implemented several precautions to ensure accurate comparisons between our fibers and other materials. Initially, we standardized the electrical outputs by factoring in the planar area of the devices’ triboelectric layer and electrodes. Additionally, we limited our analysis to materials with a fibrous morphology. Lastly, we refrained from examining devices that contained materials polarized by high-voltage treatment. In Fig. 4f, devices with all possible combinations of test protocols (single or two-electrode) and structural morphologies of fibers are included.

Biodegradation and protein leaching

Fibers were biodegraded in a beyondGreen domestic waste composter with a mixture of 75% green leafy vegetable, 23% wood chips, and 2% baking soda. Fibers were incubated for 30 days in the composter. The fiber samples were extracted carefully and subjected to mechanical testing as per ASTM standards.

Initially, fibers were kept in an oven at 60 °C for 1 h to remove moisture. 215 mg of filaments were immersed in 50 ml of DMSO at 60 °C and were continuously stirred for a day. Following the DMSO treatment, the fibers were centrifuged to remove excess DMSO. The fibers were then washed and transferred to warm ultrapure water for 1 hr. Lastly, the fibers were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 3 h and stored in a desiccator before characterization. The protein was separated from DMSO by adding excess ultrapure water after treating the filaments.

FTIR spectroscopy

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy was carried out on Bruker Vertex 70 equipped with a liquid nitrogen-cooled MCT detector using a diamond crystal accessory. The spectrum was collected at a resolution of 4 cm-1 from 400 cm-1 – 4000 cm-1 wavenumber, and 256 or 512 scans were coadded. For deconvolution of Amide I band: the raw spectra was self-deconvoluted with enhancement factor of 2 and 25 cm-1 bandwidth using OMNIC software, and the peaks were fitted using OriginPro after baseline correction.

Wide angle X-ray scattering

WAXS analysis of fibers was performed on a Xenocs Xeuss 2.0 system, operating at 50 kV and 0.6 mA current. The fibers were aligned vertically on a sample holder containing holes, allowing analysis of fibers without any intervention from foreign materials. The data were collected for 60 sec and were plotted as diffractograms and intensity plots. The obtained intensity plots were peak-fitted in OriginPro using crystalline peaks (Gaussian shape) discussed in literature. The crystallinity of fibers represents the fraction of area under the crystalline peaks (({I}_{C})) and can be estimated using the following equation:

where ({I}_{A}) is the area under the amorphous peak. The standard errors are tabulate in Supplementary Table 3.

Tensile tests

The fibers were tested mechanically on an MTS Criterion load frame with 10 N load-cell and spring-loaded clamp-type grips, as shown in Fig. 2d. The tensile testing was carried out by the standard ASTM D3822 – 07, and a gauge length of 25 mm was maintained across all samples. Ten replicates for all fiber types were performed. Fiber toughness and modulus were estimated using the collected raw tensile data.

Scanning electron microscopy

SEM micrographs were acquired on ThermoScientific Verios G4 FESEM. For sample preparation, fibers were immersed in liquid nitrogen and fractured to reveal pristine fiber cross-section. The fibers were adhered to the side of a sample stub facing upwards, and the cross-sections were sputter coated (Leica) with iridium to a final thickness of ≈7 nm. Images were collected at voltages and currents ranging from 2 kV – 5 kV and 50 pA – 0.2 nA, resp.

Responses