Mitigation potential of antibiotic resistance genes in water and soil by clay-based adsorbents

Introduction

The development of antibiotics has had a tremendous impact in various fields, especially when it comes to the production of pharmaceuticals, animal feeds and pesticides. The global consumption of antibiotics has increased disproportionately in recent years. It is estimated that in 2030 the global use of antibiotics will increase by 200% in comparison to 2015 if adequate policy measures are not taken1. In crop agriculture, livestock, and poultry farming and human healthcare, various antibiotics are extensively used worldwide to treat bacterial infections, promote livestock growth, and cure human diseases although the consequent ecotoxicity is becoming a growing concern.

Antibiotics are frequently used in plant protection, animal production, and human health management2. For example, antibiotics such as streptomycin, oxytetracycline, and kasugamycin are used worldwide for controlling major bacterial plant diseases. This raises concerns about their potential yet unknown impact on antibiotic and multidrug resistance and spread of their genetic determinants among bacterial pathogens. The residues of antibiotics used in farmlands, fisheries, aquaculture, food animals, companion animals and humans discharged into the environment could influence the three key mechanisms—transformation, transduction, and conjugation—by which bacteria acquire and transfer genetic material, including ARGs3. These processes contribute to the evolution and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in microbial populations in the environment4. Additionally, pre-existing resistance genes from diverse bacterial flora, aided by the action of insertion sequences, gene cassettes and transposons, can be transferred onto large mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as plasmids, enhancing their mobilization between bacterial cells4.

ARGs are ancient, predating the rapid rise in the use of antibiotics in clinical and agricultural settings over the past century5. ARGs have been identified as Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CEC), which have been identified as one of the most significant challenges to human health by the World Health Organization (WHO)6, and are more difficult to control than traditional chemical pollutants7. The removal of ARGs in contaminated water and soil matrices is therefore challenging.

There are only a few strategies that can remove ARGs from contaminated water and minimize transport/transmission in soil. The ARGs removal methods from water include oxidation, membrane separation, chlorination, adsorption, sludge activation and anaerobic treatment of effluents8. The sludge activation process may cause secondary toxicity hazard and the residual bacteria may cause health risk after disinfection9. Anaerobic digestion requires a high temperature, and the maintenance cost is high10,11. Most of the above approaches are energy-intensive, expensive, and less ecofriendly. The adsorption method of removing ARGs from water has received increasing interests over the years due to its high efficiency for removal, inexpensive nature, consumption of less energy and wide range of acceptance among users12.

Clay mineral-based adsorbents have attracted widespread research attention due to the wide abundance of these natural materials, high specific surface area, high cation exchange capacity, easy ways to modify their surface properties and less chance of producing secondary pollution13,14. However, natural clay minerals sometimes show low efficiency during bulk removal of target contaminants and subsequent desorption of contaminants. Modification and surface functionalization of clay minerals with different inorganic and organic agents can enhance the contaminants removal efficiency by increasing the diversity of surface functional groups and engineering the surface charge, thereby improving the capacity and selectivity of adsorption15,16,17.

A few reports concerning adsorbents for ARGs mitigation in contaminated water and soil is currently available8,18,19, but no perspective paper has been published to date focusing on ARGs removal using natural and modified clay minerals. The current paper aims to provide a critical insight into the opportunities and challenges of using clay-based materials for AMR mitigation in water, wastewater, biosolids, and soil, and proposes future research directions to ensure that this remediation technology becomes effective and sustainable at a large scale. Here, we discuss the sources, distribution, and ecological risks of ARGs and mechanisms concerning their interactions with natural and modified clays and clay minerals. We shed light on critical factors affecting the interaction of ARGs with clay-based materials and propose future research directions to overcome the issue of poor adsorption and/or fast desorption.

Ecological and human health risks of ARGs

AMR genetic acquisitions empower bacteria to withstand antimicrobial selection pressures, including residues of antimicrobials, metals, biocides, industrial and pharmaceutical chemicals, rendering pharmacological agents used to control or eradicate pathogens partially or completely ineffective4. In certain instances, antimicrobial selection pressures can favour and propagate multiple drug resistance (MDR), characterized by resistance to three or more classes of antibiotics, through a single genetic exchange. Resistance genes may be harboured by non-pathogenic bacteria, such as commensal bacteria, and transmitted to pathogenic bacterial hosts, making healthy humans, animals, and environmental bacterial populations carriers of ARGs. Although AMR is a natural occurrence in bacteria, MDR has surged significantly since the introduction and widespread use of antibiotics for treating human, animal, and plant diseases. Resistance, often MDR, is on the rise in both hospital and community-acquired bacterial infections, as well as in intensive animal and plant production systems worldwide.

ARGs enter the human body through water, air, soil, food, contact with humans, companion animals, wild animals, and the environment20. For example, Escherichia coli is an opportunistic pathogen, the most widely used indicator for faecal bacterial contamination according to water quality standards, had been reported to carry Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases (ESBL)-producing E. coli and sulfonamides through consumption of poor-quality drinking water21.

Tolerance to chlorine is considered as a vital factor for ARGs risk assessment22. Discharge from industrial effluents and their deposition in the river may cause ecological health risk of aquatic microorganisms. For instance, the concentration of antibiotics in the Karst River in China was higher in the winter than that in the summer, and there were significant differences in the structure of bacterial community and ARGs between the seasons23. In a study comparing ARGs present and their risk ranks in biofilters of surface and groundwater, it was found that the abundance of rank I, rank IV, and unassessed ARGs were significantly higher (p < 0.001) in surface water biofilters than in groundwater biofilters24. Specifically, the abundance and percentage of the highest-risk-rank ARGs (rank I) in surface water biofilters (4.17 × 10−3 ARGs copies/cell; 0.462% of total ARGs abundance) were approximately 102 times and 16 times higher than that of groundwater biofilters (4.07 × 10−5 ARGs copies/cell; 0.028% of total ARGs abundance), respectively24. The much higher abundance of the highest-ranked ARGs in surface water biofilters than in groundwater biofilters could be partially because surface water was more prone to ARGs-enriching contamination of antibiotics and heavy metals before being used for drinking purpose24.

However, the ecotoxicity of ARGs (e.g., tetA (60), tetT, and otr(B)) could be reduced due to the production of intermediates during antibiotic degradation (e.g., tetracycline) that could significantly change the microbial community structure25. A significant decrease in basal respiration (SR) was reported for soils containing sulfamethoxazole, sulfamethazine, sulfadiazine, and trimethoprim antibiotics while sulfamethazine had a significant short-term negative impact on the activities of dehydrogenase and urease enzyme26. Risk quotient (RQ), a parameter to ecological risk assessment for any pollutant, is the ratio of the measured environmental concentration (MEC) to the predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC). RQs <0.01 represents the lowest risk; 0.01 ≤ RQs <0.1 is considered as low risk; 0.1 ≤ RQs <1 indicates moderate risk; and RQs ≥1 represents high risk27. Among all antibiotics analyzed that occurred in agricultural soil, norfloxacin and chlortetracycline had a medium risk with a median RQ of 0.173 (Wilcoxon test: p < 0.01) and .061 (p < 0.05), respectively28. Therefore, the dominant ARGs belonging to dominant antibiotic groups (e.g., aminoglycosides, multidrug, macrolide-lincosamide-strepto-gramin B) may cause ecological risk to a high extent29. Thus, ARGs may adversely affect the soil health and microbial activities and bring ecological risks towards living organisms and humans26.

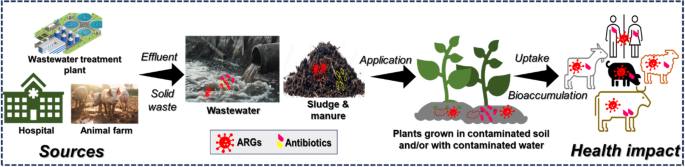

Discharges from stormwater, agricultural, aquacultural and industrial runoff, hospital, and domestic effluents are the main sources of antibiotic residues and ARGs in wastewater. Antibiotic residues and ARGs can enter the environment through wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents (Fig. 1). A recent study revealed an increasing prevalence of clinical antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) from north to south in Europe30. Comparing the influent and final effluent of 12 wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) located in seven countries (Portugal, Spain, Ireland, Cyprus, Germany, Finland, and Norway), researchers identified 229 resistance genes and 25 mobile genetic elements using polymerase chain reaction30. This first trans-European surveillance showed that WWTP ARG profiles mirror the gradient of ARGs observed in clinics. Antibiotic use, environmental temperature, and WWTP size were important factors related to resistance persistence and spread in the environment. Similarly, metagenomic analysis of sewage water from 79 sites across 60 countries showed differences in the diversity and abundance of bacterial resistance between Europe, North America, and Oceania compared to Africa, Asia, and South America31. The study suggested that global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene diversity and abundance vary by region and that improving sanitation and health could potentially limit the global burden of AMR31.

Sources, distribution, and impact of ARGs in the environment.

Numerous studies have highlighted the widespread presence of certain antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) like sul1, ermB, and tetW in various environmental settings. For instance, research conducted on 62 wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in the Netherlands revealed sul1 and ermB as the predominant ARGs in wastewater32. In another study, conducted in the city of Harbin, China, high concentrations of tetW were detected in the influent of four WWTPs, ranging from 106 to 107 copies/mL33. Additionally, in wastewater from Wuhan, China, all ARGs tested were detected at a rate of 100%, with tetracycline reaching a concentration of 1708.33 ng/L, and the highest absolute abundance observed for sulfa ARGs34. Further investigations into non-point source discharges from 26 tributaries into China’s Erhai Lake revealed the prevalence of ARGs such as mexF, sul1, and sul235. These findings collectively suggest that WWTPs serve as both sources and sinks of ARGs, with sewage, sludges, and effluents being primary contributors to environmental ARG levels.

As wastewater recycling becomes increasingly essential for water-scarce regions, it’s crucial to ensure proper treatment, monitoring, and management practices. Water recycling offers a sustainable water source, but it also presents risks associated with emerging contaminants, including enteric opportunistic pathogens (EOPs) and ARGs36. Various studies have consistently found EOPs and ARGs in municipal wastewater and treated effluents, leading WWTPs to be identified as antimicrobial resistance (AMR) hotspots37. The exposure of WWTPs to antibiotic residues and other pollutants, along with treatment processes, can stimulate the selection and spread of EOPs and ARGs, potentially facilitating horizontal gene transfer38,39.

The use of treated wastewater for irrigation poses additional risks, as it can introduce ARGs and other contaminants into soils. Crops irrigated with recycled water can absorb antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and ARGs, which may pose a risk to consumers40,41. Moreover, soil itself can serve as a reservoir for antibiotic residues and resistance genes, sourced from various inputs such as manure, biosolids, pesticides, and wastes. Livestock farming practices significantly contribute to the presence of ARGs in soils, with different types of manures influencing the diversity and concentration of ARGs. Effluents from agricultural activities, municipal solid wastes, plastic wastes, and landfills also contribute to the dissemination of ARGs alongside other contaminants42,43. Factors such as soil organic matter, microbial community structure, and soil fertilization practices can influence the variability and abundance of ARGs in soil42,44, ultimately impacting soil quality for agricultural purposes. Overall, understanding the sources and dynamics of ARGs in environmental matrices is essential for effective AMR management and public health protection.

Factors affecting ARGs transfer and transformation

The presence of soil minerals, organic matter, and surface-active particulate materials such as biochar and microplastics, which add organic matter to soil, greatly influences the transfer of ARGs in contaminated media. Extracellular DNA-mediated transformation is an important and widely occurring pathway for horizontal transfer of ARGs in the soil environment. The soil consisted of clay minerals such as kaolinite, montmorillonite and quartz, and organic constituents such as humic acid, char, and soot, were evaluated for ARGs transformation by Shi et al.45. It was revealed that a small amount in suspension (0.2 g/L) of most soil components (except for quartz and montmorillonite) promoted transformant production by 1.1–1.6 folds45. In contrast, under high suspension concentration (8 g/L), biochar enhanced the bacterial transformant by 1.5 folds, and kaolinite had 30% inhibitory effect45. The biochar produced more supercoiled plasmid than kaolinite due to the presence of dissolved organic carbon and metal ions present in biochar45. Another study showed that 1–2 g/L kaolinite and montmorillonite had limited effect on the transformation of ARGs, while 10 g/L kaolinite and montmorillonite inhibited it46. In contrast, other studies concluded that montmorillonite promoted transformation at 0–0.025 g/L and inhibited transformation at 0.025–2 g/L in soil pore water system47. Therefore, the properties (charge and surface area) of clay minerals and soil pH might have played an important role in ARGs transmission. Under acidic soil pH, montmorillonite due to its high specific surface area may contribute to nutrient deficiency and adsorption of nucleic acids and ARGs, which could inhibit the transmission. Therefore, clay minerals’ charge and surface area appear to be the most important factors for limited ARGs transmission and transformation by clay minerals. On the other hand, low concentration of organic matter or humic acid may have little promoting effect on transformant production due to lesser activity of microorganisms in soil under low organic matter concentration. For example, animal manure, one of the primary sources of ARGs in soil, increases the bacterial diversity, population and organic matter content of soil. Application of animal manure not only increases the abundance and mobility of ARGs, but also introduces antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pathogens into agricultural soil48. In addition, the diversity and abundance of ARGs have obvious differences in the different types of animal manures. For instance, swine and poultry manures have significantly higher ARGs diversity than the cattle manure49. However, the presence of indigenous microorganisms in soil also inhibits ARGs dissemination from animal manure to soil. Thus, microorganisms play a vital role in transmitting the plasmids and promote transduction of the genetic materials50. Yu et al.51 reported that sulfonamides could promote the proliferation of ARB. Under heavy metal stress, microorganisms would be prone to produce heavy metal resistance genes (MRG). In addition, heavy metals and residual antibiotics could result in synergistic selective pressure, which could increase the abundance of ARGs in microbial communities12. For example, chlortetracycline in the presence of Cu (II) severely affected the removal of ARGs in an anaerobic digestion process52. Conjugative transfer involves the transfer of ARGs by MGEs from donor cells to recipient cells by direct contact between cells53, while transformation refers to the process in which the recipient bacteria bring extracellular ARGs into their genome and obtain resistance54. Transduction involves the process of phage transferring ARGs from a donor cell to a recipient cell55. Vesiduction is associated with the vesicles secreted from the surface of donor cells. These vesicles transport DNA containing ARGs into the cytoplasm of recipient cells by fusing with the cell membranes of recipient cells56. It is noteworthy that MGEs are indispensable vectors in these processes, i.e., plasmids carry other MGEs, mediate the conjugation process and can be transformed by bacteria from the environment. The insertion sequences and transposons can transfer the ARGs between plasmids or between plasmid and chromosome. The integrons can insert gene boxes carrying ARGs into transposons or plasmids to spread antibiotic resistance. The phages are responsible for the transduction process57. Heavy metals affect HGT mainly by accelerating the conjugation mediated by plasmids, which is mostly achieved by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the permeability of cell membrane58. Overall, organic matter, soil clays and clay minerals, microorganisms, and their functionality, and heavy metal stress directly impact the transfer and transmission of ARGs in contaminated soil and water.

Removal and mitigation of ARGs by clay-based adsorbents

Naturally available clay minerals (e.g., montmorillonite, bentonite, and kaolinite) have capacity to adsorb antibiotics and ARGs due to their relatively high surface area, layered structure, surface charge and cation exchange capacity59. For example, tetracycline adsorption was observed onto montmorillonite and kaolinite clay minerals through cation exchange and hydrophobic interactions15. However, clay minerals may suffer from poor adsorption capacity and high desorption ability of organic compounds depending on the ionic behavior of the target compounds (e.g., negatively charged clay mineral surface may have less affinity to anionic organic compounds)60. Different modification processes such as acid activation, pillaring of clays and surfactant modification were performed to improve the surface reactivity and antibiotic adsorption capacity of clay minerals17,61. Besides, biowaste-derived biochar and/or organic modifier was used to support clay minerals in the form of mineral-biochar composite to functionalize clay minerals62,63 (Table 1). Polymers and layered double hydroxides64 were also used for enhancing the capacity and accelerating the rate of clay minerals to remove contaminants of emerging concerns including antibiotics, which could inhibit the development of ARGs65. For instance, in a recent study a novel sodium-alginate montmorillonite bead was shown to remove tetracycline from water to the level of 745 mg/g as compared to natural montmorillonite (445 mg/g)16, which indirectly helped to prevent ARGs development in wastewater. The mechanisms for the adsorption or removal of antibiotics might include hydrogen bonding, cation exchange phenomenon, hydrophobic interaction, and electrostatic attraction16.

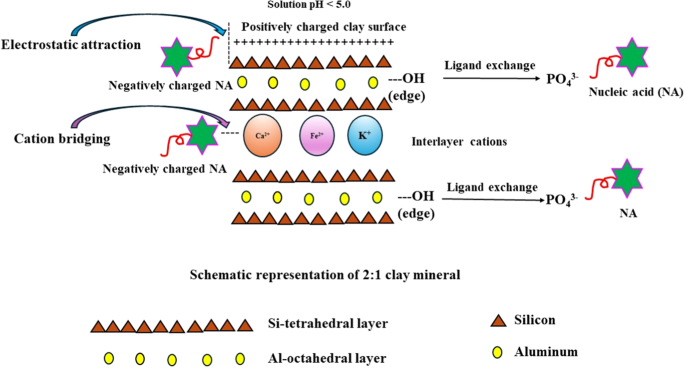

Natural and modified clays and clay minerals can interact with cell nucleic materials too in wastewater and soil (Fig. 2)66. Ligand exchange and/or direct binding of phosphate groups at the two ends of nucleic acids to the hydroxyl groups of clay mineral surfaces give rise to interactions of nucleic acids with clays and clay minerals. Montmorillonite and kaolinite could adsorb nucleic acids on their surfaces in the presence of divalent cations via a cation bridging mechanism and inhibit the dispersal of nucleic acids in wastewater and soil66.

The interaction mechanisms mainly include electrostatic attraction, cation bridging and ligand exchange depending on prevailing environmental conditions.

Clays and clay minerals can inhibit the horizontal transfer of ARGs by adsorbing antibiotics and/or eDNA, which efficiently reduces the abundance of ARGs in environmental matrices67. For example, montmorillonite and kaolinite were shown to reduce the ability of B. subtilis to transform eDNA through the strong adsorption of competence-stimulating factor and down-regulation of transcriptional genes46. Similarly, kaolinite was reported to control the gene expression pattern and metabolism of bacteria adsorbed on the mineral surface, decreasing the risks of the spread of ARGs under low antibiotic stress conditions68. Kaolinite and montmorillonite also inhibited the protection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to sensitive bacteria, which reduced the development of cooperative resistance and controlled the transmission of ARGs20. However, the concentration and particle size of clay minerals might have different effects on the HGT process. A study by Hu et al.47 reported some remarkable effects of different concentrations and particle sizes of montmorillonite on the horizontal transfer of ARGs. A low concentration of montmorillonite (0.001–0.100 g/L of size 1568 nm, 0.001–0.050 g/L of size 568 nm, and 0.001–0.025 g/L of size 300 nm) enhanced HGT, which might be due to Al3+ release from montmorillonite that induced cell membrane damage (hole formation) and promoted plasmid transfer into cells47. In contrast, the transformation of ARGs was inhibited at a high concentration of montmorillonite (0.1 g/L) due to the binding of the plasmids to montmorillonite47. The adsorption of DNA onto clay minerals could depend on the structural properties of the clay minerals and structure and molecular weight of the concerned DNA. Since the molecular weight of DNA is high, it has a natural tendency to be attached with clays and clay minerals38,69. Another important factor is the pH and ionic strength of the medium. The adsorption of DNA is favourable at pH > 5.0 in the presence of interlayer cations of the clay mineral and solution cations such as Fe2+, K+ and Ca2+ through cation bridging, whereas a low pH (pH <5.0) could favour electrostatic attraction of DNA (having amino groups as the functional units and being protonated at low pH) on the edges of clay minerals with a dominance of broken Al-O groups, similar to the mechanisms involved in nucleic acid adsorption on clay minerals67,70 (Fig. 2). Literature on ARGs adsorption by clay minerals are very scanty, but the main mechanisms such as electrostatic attraction, cation bridging, and ligand exchange can be assumed to be involved in ARGs adsorption. Bentonite clay, in which montmorillonite is the main clay mineral phase, was reported to effectively reduce ARGs and prevent HGT owing to the mineral’s enhanced attenuation of intI171. Bentonite could also promote the degradation of ARGs and antibiotic residues due the mineral’s high water and nutrient retention capacity and high specific surface area. Antibiotic degrading microorganisms could be attracted on the surface of bentonite through retained nutrients and high surface area60. These microorganisms take energy from the clay-retained nutrients and utilize carbon from antibiotics, degrading the compounds72. This process thus reduces the transfer of ARGs on the clay mineral surface. Microporous zeolites, another class of geomaterials or minerals, may also inhibit the transfer and abundance of ARGs73. Zhou et al.74 reported that the addition of zeolite inhibited the abundance of intI1 (represents HGT potential) by increasing the distance among microorganisms and reduced the frequency of microbial contact, thereby controlling HGT between bacteria and reducing the risk of ARGs dissemination during composting of organic matter74 (Table 1). In this connection, a novel photocatalytic composite made from delaminated kaolinite clay and doped with Cu/Zn was able to degrade ARGs under visible light condition in water75. The study by Ugwuja et al.75 revealed that the photocatalytic composite kept a multidrug resistant E. coli and its sulfonamide resistance genes in contaminated water at log reduction >6 for 36 h in two disinfection steps under visible-light in a fixed-bed operation mode. In contrast, fluoroquinolone resistance genes persisted in the treated water after the first disinfection step and were significantly reduced after the second disinfection step75. The authors suggested that surface oxygen vacancies were mainly responsible for the photoactivity of the composite towards ARGs control and no bacterial regrowth occurred in the treated water stored in light/dark for 7 days75. However, adsorption of eDNA by kaolinite showed a reduced degradation of ARGs by DNase76. Therefore, future research needs to unravel the vesiduction and transduction of ARGs when concerned DNA would be interacting with various types of clays and clay minerals under natural environmental conditions.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Antibiotic residues and ARGs are widely distributed in the water and soil environments and have massive ecological risk to animal and human beings. The retention, transformation, and degradation of antibiotics and ARGs are highly regulated by soil clays and clay minerals alongside other factors such as soil organic matter content, soil texture, pH and climate, while the removal of antibiotics and ARGs from wastewater could be facilitated by natural and modified clays and clay minerals. The clay-based adsorbent has attracted wide research attention in the recent years, specially to control contaminants of emerging concern. During the fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly in 2021, institutions including World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization emphasized to develop guidelines for minimizing environmental pollution using nature/bio-based solutions77. It is indeed an opportunity for scientists and policy makers to explore the potential of clays and clay minerals for mitigating the ARGs issues in the water and soil environment and evaluate the performance of clay-based materials under natural field conditions. To promote the remediation of ARGs using natural and modified clays and clay minerals and clay-carbon composite adsorbents, future research should address the following issues and knowledge gaps:

-

(1)

Global survey and source identification of antibiotic residues and ARGs contamination, and a comprehensive understanding of the nature of ARGs spread in the environment are needed before any remediation approach can be implemented at large scale78.

-

(2)

Future studies are needed to explore the adsorption capacity and mechanisms of ARGs on various types of clay minerals and find environmentally benign methods of clay functionalization to improve the adsorption capacity and durability of products.

-

(3)

Advance functionalization of clay minerals with graphene oxide, metal organic framework, zeolites, biochar, and nanoparticles (metal oxides) can destroy the structure of ARGs in soil and water environment, however, their environmental implications need future research. Modification of clay minerals with long chain surfactants, polymers and amines may enhance the surface charge and functional groups on the surface of minerals, which can adsorb eDNA more strongly, protecting its degradation by DNase and reduce the transmission and transfer for ARGS in the environment.

-

(4)

Generation of integrative data bases on ARGs are essential along with additional data on uncharacterized ARGs for routine monitoring. Whole-genome and transcriptome analyses including next-generation sequencing technology can be new possibilities for understanding the resistance mechanism and remediation efficiency in environmental compartments38.

-

(5)

Understanding the mechanisms of ARGs degradation, factors influencing the degradation (such as pH, competing ions, temperature, redox potential.) is a need of the hour for efficient water and soil treatment.

-

(6)

Application of amendments for soil remediation requires large scale field testing instead of spot-by-spot monitoring to clinically understand the effectiveness of the amendments to control antibiotic residues and ARGs. Heterogeneity in soil properties (e.g., texture, structure, pH, ionic strength, organic matter content, cation exchange capacity) need to be considered in investigations involving a large amount of amendment applied to a large area.

-

(7)

Novel, easily operable and inexpensive detection methods should be developed for improved monitoring of ARGs and to determine the trend of fragmented and degraded ARGs products. These facilities should be available at on-site wastewater treatment plants and soil research stations to monitor the efficiency of ARGs remediation.

Responses