Microwave catalytic pyrolysis of biomass: a review focusing on absorbents and catalysts

Introduction

The high consumption of global energy has gradually driven up the prices of conventional fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, which have finite reserves. In 2022, Brent crude oil prices reached their highest level since 2013, averaging $101 per barrel. In Europe, natural gas and coal prices have increased by 300% and 145%, respectively, compared to 2021. These fluctuations could trigger sharp shocks in the energy market, posing risks to both global energy security and political stability. Another daunting aspect is the record-high global carbon emissions, reaching 39.3 billion tons in 2022, with emissions from fossil fuel consumption accounting for 71% of the total global emissions1. In response to the problem of global warming caused by carbon emissions, 178 countries around the world signed the Paris Agreement in 2016, which sets a long-term goal of limiting the increase in global average temperature to less than 2 degrees Celsius, or even 1.5 degrees Celsius, from the pre-industrial period2. In light of these challenges, development of clean and low-carbon renewable energy to partially replace fossil fuels has received increasing attention3.

Biomass stands out among various renewable energy sources as the only one capable of producing both chemicals and liquid fuels. In addition, it is widely distributed, low in sulfur and nitrogen, and boasts zero net carbon dioxide emissions throughout its entire life cycle of growth and utilization. The global biomass resources are abundant, estimated at 144-180 billion tons per year, equivalent to about 10 times the world’s total energy consumption4. According to the latest data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2022, modern biomass energy has become the largest renewable energy source globally, holding a 55% share of the renewable energy end market, surpassing the combined share of wind, solar, hydro, and geothermal energy5. Despite the dominance in the renewable energy section, biomass energy constitutes only 6% of the global total energy supply chain, far lower than the 82% contribution of fossil fuels1. This discrepancy may be attributed to the prevalent use of direct combustion as the primary mode of biomass energy utilization, resulting in low energy conversion efficiency. Another crucial factor is the underutilization of many biomass resources, raising concerns about potential environmental issues. For instance, it has been reported that globally dead wood, if left to rot, releases annually 115% of the carbon released by humans6. In addition, the decay of biomass forms methane (300-400 m3 of methane /1 ton of decayed biomass7), which has a greenhouse effect more than 20 times that of carbon dioxide. The flammable and explosive nature of methane poses a risk of forest fires. Therefore, utilization of biomass resources is imperative for achieving carbon neutrality.

Biomass proves to be versatile in generating a range of chemicals, fuels, materials, as well as heat and electricity, through different technological pathways such as biochemical conversion, pyrolysis and gasification8. Among them, biomass fast pyrolysis technology has gained significant attention in recent years due to its cost-effectiveness and high liquid yield9. Biomass undergoes a series of reactions such as large molecule bond breaking, isomerization, and small molecule polymerisation at high temperature under anaerobic or anoxic conditions, and is ultimately transformed into low molecular weight volatile components (bio-oil and gas) and char/coke10. However, the bio-oil produced from direct pyrolysis of biomass suffers from its complex composition, low calorific value, strong acidity, and poor stability, making it challenging for practical applications such combustion for heat or extraction of high-value chemicals11. Currently, the composition of biomass pyrolysis oils is primarily controlled and regulated through pretreatment, catalysis, and bio-oil hydrodeoxygenation to achieve highly selective production of levoglucosan, levoglucosan ketone, furfural and aromatics12,13,14. Among them, catalysis stands out as the most effective and economically promising pathway for quality improvement of bio-oil before it condenses14. In contrast to the conventional heating mode that transfers heat through conduction, convection, and radiation, microwave heating involves the conversion of electromagnetic energy into thermal energy. This unique characteristic allows for in-core volumetric heating, overcoming the limitations of conventional heating method in terms of reactor structure and raw material particle size. Microwave heating exhibits lower demands on the size, shape, density and thermal conductivity of the material. It also offers advantages such as high heating rate, controllability, and energy efficiency compared to conventional heating method. Moreover, the unique phenomena of hotspots and microplasmas that occur during microwave heating can play an important role in thermochemical reactions.

This review focuses on the application of microwave in the catalytic pyrolysis of biomass, starting from the theoretical background of microwave heating. Then it delves into the characteristics and differences between direct microwave pyrolysis and microwave-assisted pyrolysis, emphasizing the role of microwave adsorbents. Potential catalysts suitable for microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass are reviewed, with a specific focus on catalysts exhibiting microwave absorption properties. The energy efficiency, economic feasibility, and environmental impacts of this processing technology utilizing microwave absorbents and catalysts are examined based on energy analysis, techno-economic assessment (TEA), and life cycle assessment (LCA). The current scale-up challenges of microwave catalytic pyrolysis of biomass are also reflected upon, and some potential solutions are proposed for better commercialization of this technology. Finally, some future development directions about this technology are given.

Theoretical background of microwave heating

Principle of microwave heating

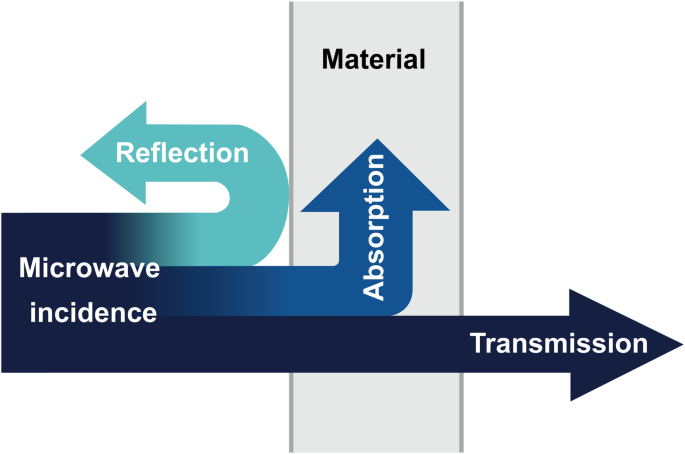

Microwave refers to electromagnetic wave with frequencies from 300 MHz to 3000 GHz15. The magnitude and spatial distribution of its energy depend on the transmission, reflection, and absorption of electromagnetic wave in the materials, as shown in Fig. 116. Microwave transmissive materials can transmit electromagnetic wave without significantly changing its nature (including energy), common examples including most polymer materials and some non-metallic materials. Microwave reflective materials mainly consist of highly conductive metals, such as gold and silver. Microwave absorbing materials are designed to neither easily reflect nor completely transmit microwave, necessitating good impedance matching and strong microwave loss. Loss is categorized into dielectric and magnetic loss. Dielectric loss includes interface polarization, dipole polarization, and conductive loss. Magnetic loss includes natural resonance, hysteresis loss, and eddy current loss. Microwave absorbing materials of dielectric loss are mainly ceramic-based and carbon-based materials, including silicon carbide, graphite, and carbon materials. Microwave absorbents of magnetic loss mainly include ferrite and magnetic metal particles (Fe, Ni, Co and their alloy powders).

Transmission, reflection, and absorption of microwave in materials.

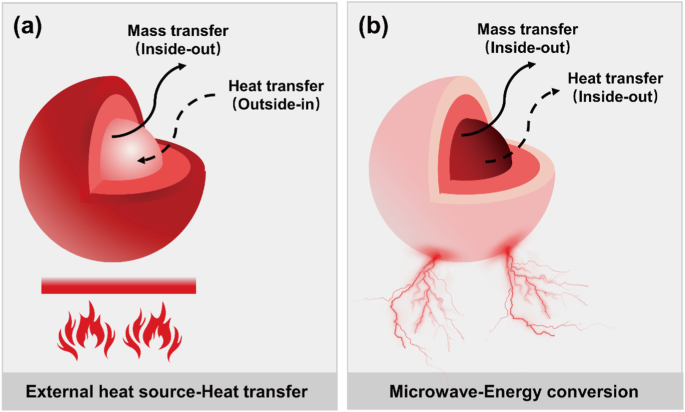

The electromagnetic wave lost within the material is converted into heat, making microwave heating a non-contact and volumetric heating method. Microwave heating occurs from the inside to the outside, which is the main difference from conventional heating method. This also leads to consistency in the direction of heat and mass transfer during microwave heating (Fig. 2). In addition, microwave has the characteristics of selective heating, resulting in a substantial overlap between the thermal sites in the reaction system and the material reaction sites. This eliminates the heat conduction process required by conventional heating method. Therefore, microwave pyrolysis operates at lower temperatures, accelerates the reaction rate, and manifests a lower apparent activation energy17. The ability of materials to absorb microwave and convert it into heat is commonly represented by the magnitude of the loss angle tangent (tanδ). In general, tanδ greater than 0.5 indicates that the material has a strong microwave absorption ability, while value less than 0.1 suggests a weak microwave absorption ability18. Table 1 lists some common materials of different categories and their loss angle tangent values.

a Conventional heating involving heat transfer with an external heat source. b Microwave heating involving energy conversion (microwave energy to thermal energy).

Unique phenomena of microwave heating

The hotspot phenomenon due to localised overheating is one of the most common microwave unique phenomena. The formation of hotspots requires three conditions: (1) non-uniform distribution of materials with different dielectric losses; (2) Microwave fields with non-uniform distribution; (3) Different heat conduction velocities within the reactants19. The generation and distribution of hotspots are strongly influenced by factors such as microwave power, electric field intensity, particle size, and distance between particles20,21,22,23. Hotspots have a positive effect on promoting the thermal conversion of biomass24 and the self-gasification of tar25,26. However, in some cases, hotspots may cause thermal runaway, leading to issues such as reactor burnout and reactant coking27. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct in-depth research on the characteristics of hotspots including temperature rise and positional changes in microwave chemical reactions, in order to better test and control hotspots and provide reference for related microwave chemical reactions and microwave reactor design.

Microplasma effect is another unique phenomenon that may occur during microwave heating. Unlike dielectric materials that absorb microwave, when microwave-conductive materials such as metals with sharp edges, tips or sub-microscopic irregularities are irradiated by microwave, they reflect the microwave with the occurrence of electrical discharge and the formation of corona, spark, or arc that can trigger microplasma formation as well as heat and photocatalytic reactions28,29. The formation and properties of microplasmas are strongly influenced by the microwave output power and the dielectric strength, size, mass, conductivity, morphology and surface condition of the metal30. Plasmas are known to significantly promote chemical reactions due to their high density of free electrons with high temperature and high energy and their ability to produce ions via the ionization of molecules, atoms, and radicals. They are beneficial in biomass utilisation or organic waste treatment29,31.

Application of microwave in catalytic pyrolysis of biomass

Direct microwave pyrolysis of biomass

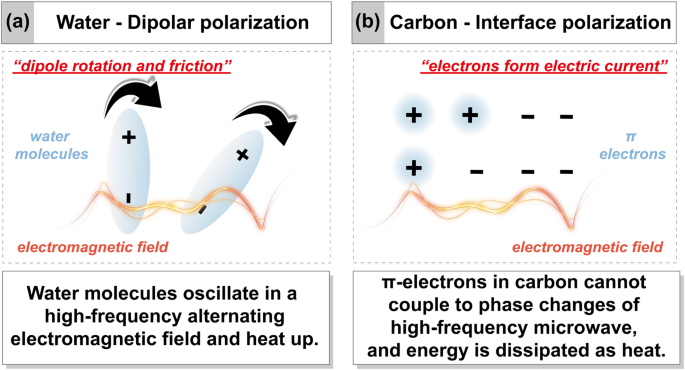

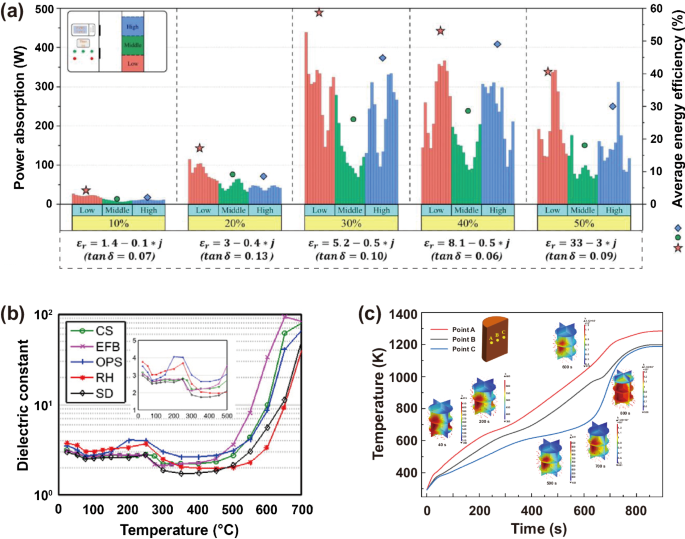

Lignocellulosic biomass consists mainly of cellulose (30–50%), hemicellulose (20–40%) and lignin (10–20%), with small amounts of water and inorganic minerals14,32. The dielectric properties and temperature distribution of biomass during microwave pyrolysis exhibit complex fluctuations in response to changes (including content, molecular structure, etc.) in these components. During start-up heating of biomass, water (including free and bound water) present in the biomass serves as the primary microwave absorbent, significantly contributing to the dielectric properties of biomass33. Since the water is dipolar, microwave irradiation increases dipole repositioning, and the dipole rotation generates friction, rapidly generating heat (Fig. 3a)34. Zi et al. found that when the moisture content of tobacco stems was 10%, microwave power absorption was little due to a low loss tangent35. The increased moisture content of biomass allows for more flexible ion migration and enhanced dielectric properties36. Microwave power absorption generally increased with increasing moisture content, peaking at 30% moisture content. However, increase in absorption was not significant when the moisture content was higher than 30%35, as shown in Fig. 4a. It is well known that moisture is regarded as an unfavorable component in conventional pyrolysis because it affects the pyrolysis efficiency and the product quality. Therefore, energy-intensive drying step is usually required before pyrolysis for conventional pyrolysis37. In contrast, water plays a positive role in microwave heating. Some scholars have explored impregnating wood particles with water to increase microwave absorption, thus promoting wood pyrolysis38. As the temperature increases from room temperature to approximately 100 °C, the dielectric properties of biomass decrease rapidly with the release of surface and weakly bound water molecules from biomass (Fig. 4b)36. It is well known that water has a significant latent heat of evaporation and absorbs a large amount of heat during its evaporation39, which is reflected in the temperature curve by a significant slowdown in the temperature rise (Fig. 4c). It is worth mentioning, however, that water vapor has a high heat capacity and spreads through the material, smoothing out irregularities in heating.

a Microwave heating of water based on dipolar polarization mechanism. b Microwave heating of carbon based on interface polarization mechanism (Maxwell–Wagner effect).

a Dielectric properties, power absorption and average energy efficiency at different positions in the cavity of biomass samples with different moisture contents35. b Dielectric constant change of different types of biomass during the heating process (CS coconut shell, EFB empty fruit bunch, OPS oil palm shell, RH rice husk, SD sawdust)58. c Temperature curves at three points inside the wood particle and the intraparticle temperature distributions during microwave pyrolysis65.

After dehydration of biomass, the polar functional groups (mainly hydroxyl groups) in its components are potential contributors to microwave dielectric heating. It is a well-known fact that the energy of microwave photon is much lower than that of any chemical bond not even enough to break the hydrogen bond (Tables 2 and 3)40,41. However, the CH2OH groups are strongly involved in hydrogen bonding, resulting in low degrees of freedom and difficulty in rotation42, which largely blocks their interaction with microwave. Only when these components are softened with the action of external heat source (benefiting from water-induced start-up heating), the enhancing of the intermolecular thermal motion and the weakening of the hydrogen bonding force allows the CH2OH groups to vibrate and rotate in an attempt to align with the microwave field43. As such they could act similarly to “molecular radiators” allowing for the transfer of microwave energy to their surrounding environment44. Research data also demonstrated that depolymerization of hemicellulose and cellulose during microwave treatment started at their respective softening points of 140 °C45 and 180 °C42. Compared to hemicellulose, the higher microwave depolymerization temperature of cellulose is attributed to the more regular and aggregated molecular structure. In detail, hemicellulose has a lower degree of polymerization (generally distributed between 100 and 40046,47) and a higher number of branched chains48, which makes its structure looser and hydrogen bonds easily broken, promoting the preferential reactivity during microwave treatment49. In contrast, cellulose has a regular chain structure and a strong inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonding network structure50,51,52 with an average degree of polymerization of about 10,00053, which elevates the difficulty of its interaction with microwave54,55. Notably, cellulose consists of both amorphous and crystalline regions with significantly different structural and thermal properties, between which the reactivity of microwave varies considerably50. Amorphous region of cellulose where the hydrogen bonding network is relatively small and localized, is more susceptible to softening (at 180 °C)42. In comparison, crystalline region of cellulose contains a very ordered hydrogen bonding network42, which raises its microwave activation temperature to 220 °C56. The predominance of the crystalline region in cellulose (about 87%)50 reduces the overall reactivity of cellulose during microwave treatment. It is worth noting that there are some interesting interactions between the amorphous and crystalline regions. Once softening occurs in the amorphous region, molecular motion increases rapidly, and then a cooperative stress is induced on the crystalline region resulting in a reduction in the level of crystallinity. In addition, hydrogen bonding network of crystalline region allows to form a proton transport network in the presence of an electromagnetic field42. The softening of the amorphous region allows movement of protons from the crystalline region causing acidity increase of the amorphous region and acid catalyzed decomposition of cellulose42. Compared to cellulose and hemicellulose, lignin contains more non-polar aromatic ring structures and few polar components such as hydroxyl groups49, thus it has the highest microwave depolymerization temperature of 200 °C57.

Once depolymerization begins, violent decomposition reactions follow. Large amounts of volatile compounds in biomass are released, which leads to a decrease in the values of loss factor until the decomposition is essentially complete (Fig. 4b)58. The dielectric properties of most biomass remain fairly constant during the latter stages of decomposition (300–450 °C) (Fig. 4b)59,60,61,62,63,64, where biomass decomposition slows down and mass loss is low. In addition, de-volatilization is an endothermic reaction and induces a hysteresis effect on the heat transfer of biomass particles, as demonstrated by a significant turning point or sometimes a plateau period in the heating curve (Fig. 4c)65. As volatiles are removed, biomass gradually evolves into solid carbonaceous products (450–700 °C). In the early stages of biochar formation, the electric field intensity inside the biochar is the largest and gradually decreases outward, which leads to the formation of hotspots in the center of the biochar66. These central hotspots inside the biochar become the driving force for the outward diffusion of pyrolysis gas (pumping effect), which promotes the formation of rich porous structure inside the biochar, allowing microwave to be reflected multiple times and gradually absorbed in the biochar66. The porous structure also enhanced the interface polarization of biochar, and further enhanced the microwave absorption capacity of biochar67. Furthermore, hotspots promote the sp2 hybridization of amorphous carbon and transform it into graphite carbon68. The π-electrons in graphitic carbon generate a current that propagates in the same phase as the electromagnetic field. Since the electrons cannot couple to changes in the phase of the electric field, the energy is dissipated in the form of heat due to interface polarization (Maxwell-Wagner effect) (Fig. 3b)69. The polar functional groups in the biochar also contributes to the absorption of microwave70. These factors result in biomass exhibiting a considerable dielectric constant during the carbonization stage, promoting an increase in pyrolysis temperature (Fig. 4b, c). It is worth mentioning that the carbon content of lignin is as high as 60%, which is significantly higher than that of cellulose and hemicellulose71,72. It is clear that lignin will be the main contributor to microwave heating at the carbonization stage due to its high char yield compared to cellulose and hemicellulose. More interestingly, char formed from lignin tends to have a higher graphitic degree and electronic conductivity. A data illustrated that lignin-derived char had graphitic degree of 89.53% and electronic conductivity of 104.6 S cm−1, while cellulose-derived char had lower graphitic degree of 76.74% and electronic conductivity of only 48.8 S cm−1 73. This is because the stable and aromatic ring containing skeleton structure in lignin was beneficial to the ring-enlarging reconstruction and the formation of large areas of continuous graphitic layers during graphitizing process, but the interwoven microcrystallites in cellulose-derived char strongly restricted the expanding of continuous lamellar graphitic areas, causing the formation of turbostratic structure with numerous structural defects, and finally resulting in relatively lower electronic conductivity.

Ash components in biomass also contribute to the temperature rise of biomass74, although there is some debate over whether this is due to the ash acting as a dielectric material. A comparison of the dielectric properties of pulp mill sludge and acid washed pulp mill sludge revealed that untreated pulp mill sludge had higher ash content and also higher tanδ75. High-ash sludge can be fully pyrolyzed without the addition of microwave absorbents76. However, in one study of coal, it was found that the presence of ash did not improve the dielectric properties until a portion of the ash structure was converted to SiC at temperatures above 1300 °C77.

In addition to the biomass composition, the position of the biomass particles in the microwave reaction chamber and the particle size have a significant effect on microwave heating, because they strongly influence the interaction between the electromagnetic field distribution within the microwave reaction chamber and inside the biomass particles. The sample has a more significant effect on microwave power absorption at different height positions in the cavity. Zi et al. divided the vertical height between the bottom of the sample and the bottom of the center of the cavity into low (0–10 cm), middle (11–21 cm), and high positions (22–33 cm), and found that strong electric field in the microwave heating system was always distributed in the low position inside the cavity no matter how the permittivity of tobacco stems changed (Fig. 4a)35. Therefore, heated samples should be placed low position in the cavity center to maximize energy efficiency in most microwave ovens78. In addition, when biomass particles are sufficiently large, they can traverse multiple high-energy microwave regions (peaks and valleys) in the microwave reaction chamber, thereby generating multiple local hotspots within the particles65. As the active sites for biomass pyrolysis reaction, hotspots accelerate the decomposition of organic matter, which is beneficial for improving the utilization efficiency of microwave energy24. The formation of hotspots accelerates the conversion of biochar, amplifies the increase of local dielectric properties, and further intensifies microwave absorption and heating within hotspots, leading to temperature runaway. Hotspots have a considerable impact on the structural homogeneity and stability of biochar. The rapid consumption of organic matter at the hotspot weakens the local mechanical strength of the carbon skeleton. Additionally, the local high temperature and pressure difference causes significant thermal and expansion stresses around the hotspot, exacerbating the expansion and collapse of the biochar pores65. From this perspective, the production of biomass-based carbon materials with uniform pores and a stable structure through microwave pyrolysis necessitates preventing the formation of local hotspots.

Many scientific articles have discussed the factors affecting microwave pyrolysis of biomass at laboratory scale, mainly including material properties (moisture content, composition and particle size, etc.) and process operating parameters (temperature, microwave power, residence time, etc.). Moisture content and composition have different influences on the dielectric properties of biomass at different pyrolysis stages. The particle size mainly affects the penetration depth of microwave in biomass particles. Due to the unique in-core volumetric heating method, microwave can process larger samples. Lei et al. reported that the volatile yields of corn stover with different particle sizes (from 0.5–4 mm) were similar under microwave heating conditions79. Therefore, the fine grinding and crushing steps required by conventional pyrolysis are not necessary for microwave pyrolysis process, resulting in substantial energy savings. However, if sample size is larger than microwave penetration depth, the area beyond the penetration depth cannot be heated, resulting in lower conversion rates and inconsistent product quality. Specific material particle size needs to be reasonably customized based on factors such as microwave frequency and material dielectric properties. Microwave processing of biomass is also strongly influenced by operating parameters. In the past decades, some researchers have tried to determine the optimal operating parameters to obtain the desired product distribution. Temperature is one of the most significant factors affecting biomass pyrolysis product yield. Appropriately high pyrolysis temperature promotes biomass cracking and thus increases bio-oil yield, and further increases in temperature promote secondary cracking reactions leading to the conversion of bio-oil to gas. In general, the pyrolysis temperature range of 400-550°C is suitable for bio-oil production14, while the higher temperature range of 700-1200°C is suitable for biomass gasification80. Since temperature measurement during high-temperature microwave processes is highly controversial, microwave power tends to be the preferred parameter for controlling microwave performance. Microwave power is directly proportional to the rate of temperature increase and also has a significant impact on product yield and quality. At high microwave power, high heating rate promotes bond breaking and volatile release in biomass. However, high microwave power also implies high power density (power density is defined as the ratio of microwave power to sample mass) when the sample mass is certain. The high power density promotes secondary conversion of the primary pyrolysis vapor, leading to more gas generation. Yu et al. found that the decomposition of corn stover was enhanced with increasing microwave power, leading to an increase in gas yield and a decrease in bio-oil yield81. Longer residence time (the duration for which biomass is subjected to microwave irradiation) increases energy consumption and reduces bio-oil yield. Yu et al. also proposed that under a certain microwave power, the dynamic evolution of gas products is a function of microwave heating time81.

Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass with the aid of microwave absorbents

Compared with conventional pyrolysis, microwave pyrolysis can overcome the limitations of heat transfer and achieve rapid heating. However, most biomass exhibits poor dielectric properties (Table 1)75,82,83,84,85,86 and often requires high microwave power to reach the necessary reaction temperature, which leads to low energy efficiency (< 40%) for the overall system65. The pursuit of high energy efficiency will in turn reduce the efficiency of biomass conversion, making it challenging to strike a balance between energy efficiency and conversion efficiency in the direct microwave pyrolysis system of biomass. It is worth noting that, as the de-volatilization reaction proceeds, the gradually formed high dielectric biochar can effectively transfer heat to the weakly dielectric biomass that has not yet undergone thermal decomposition, achieving an efficient synergy between energy conversion and heat transfer, and thus significantly improving the energy efficiency of microwave heating systems. However, the generation of biochar during pyrolysis is strongly dependent on the conversion of biomass, spatially and temporally limiting heat transfer and indirectly affecting product stability.

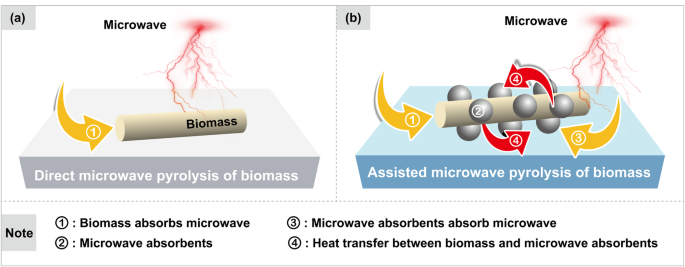

Given these considerations, if some high dielectric materials, i.e., microwave absorbents, are introduced into the reaction system beforehand and mixed with the biomass uniformly to assist microwave pyrolysis, it can simultaneously improve energy efficiency, conversion efficiency, and stability. The dielectric properties of biomass enable it to absorb microwave and heat up from within the particles, while the additional microwave absorbents transfer the heat to the surface of the biomass particles (Fig. 5). However, since the stronger dielectric properties of microwave absorbents give it an advantage in absorbing and converting microwave energy, it plays an important role in determining the pyrolysis temperature and heating rate33,87. During the microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass with the aid of microwave absorbents, most of the heat required for biomass pyrolysis comes from the heat transfer of microwave absorbents, which exhibit a stronger interaction with microwave. This is essentially consistent with the form of energy acquisition (energy transfer rather than energy conversion) under conventional heating. However, the heat transfer path in conventional heating is significantly longer, proceeding sequentially from the heated reactor surface to the surface of the biomass particles in direct contact with the reactor surface, then to the interior of these biomass particles, and finally to the biomass particles that are not in contact with the reactor surface. In contrast, the microwave absorbents, homogeneously mixed with the biomass particles, can provide efficient short-range heat transfer to the biomass in contact with them. This essentially replaces distant and non-equally spaced heat source (the heated reactor surface) with an evenly distributed short distance heat source (microwave absorbents), facilitating uniform and rapid heating of the entire reaction system. In the final analysis, it still taking advantage of microwave heating. In addition, the pyrolysis vapor escaping from biomass flows through a relatively low-temperature reaction chamber, reducing the occurrence of secondary reactions.

a Direct microwave pyrolysis of biomass. b Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass with the aid of microwave absorbents.

The type of microwave absorbents (related to microwave properties and physical properties) and the additive amount will affect the heating effect and pyrolysis product distribution of biomass. Magnetic loss-type materials will lose their magnetic properties in high-temperature environments, thus limiting their application in high-temperature reactions such as pyrolysis. In contrast, dielectric loss-type materials can meet the harsh requirements of thermal environments and are widely used in microwave pyrolysis of biomass88. Dielectric loss-type absorbents for microwave pyrolysis of biomass are mainly carbon-based materials (e.g., carbon, graphite, etc.) and ceramic-based materials (e.g., SiC). Frediani et al. compared the temperature rise and product distribution of olive pruning residue during microwave pyrolysis under the influence of carbon or SiC as a microwave absorbent. Carbon exhibited a faster heating rate, reaching 723 °C in 15 min, while SiC achieved 700 °C in 21 min. SiC condition achieved the highest yield of biochar at around 60 wt.% and the lowest bio-oil yield at 27.9 wt.%, indicating that low heating rate conditions favor biochar production. When carbon was used as an absorbent, the concentration of aromatic compounds was the highest, exceeding 180 g/L89. A similar result was found by Bartoli et al. in their study of the effect of absorbents (including carbon, graphite, and SiC) on the pyrolysis product distribution of α-cellulose. Carbon showed the fastest heating rate, resulting in the highest gasification rate (53.8%) and the highest content of water (46 wt.%) in the bio-oil. Graphite and SiC, however, showed lower water content in the bio-oil, with the former having the highest concentrations of levoglucan (133.9 mg/mL) and aromatic compounds (9.7 mg/mL)90.

In addition to microwave-related properties, some physical properties of microwave absorbents may also affect heat transfer efficiency. Taking carbon and Fe as examples, when the mass is the same, the volume of carbon is 16 times that of Fe. Therefore, even a small amount of carbon can encapsulate biomass particles effectively. Unlike Fe, carbon can be ground finer and effectively dispersed on the surface of biomass particles. In addition, the surface energy of carbon closely matches that of biomass, enhancing adhesion to the surface of biomass. The effective and sufficient contact between carbon and biomass enhances heat transfer efficiency and promotes the production of bio-oil and bio-gas91. In order to achieve more thorough contact between biomass and absorbents, liquid absorbents such as glycerol and ionic liquids can be used. Wang et al. used glycerol as an absorbent to assist fatty acid salts in microwave pyrolysis, achieving a maximum yield of 70% of bio-oil. The calorific value, density, and kinematic viscosity of bio-oil met the standard of 0 # diesel, while the freezing point and cold filter plugging point were better than those of 0 # diesel92. Similar effects have also been observed when using ionic liquid as a microwave absorbent. Guo et al. achieved the highest phenolic bio-oil yield of 21% when using butyl-4-methylimidazole chloride for microwave-assisted pyrolysis of fir sawdust93.

The additive amount of microwave absorbents mainly affects the maximum temperature and maximum heating rate, thereby changing the distribution of pyrolysis products. As the additive amount of microwave absorbents increases within a certain range, the maximum pyrolysis temperature and maximum heating rate significantly increase under the same microwave input power, transitioning from slow pyrolysis to fast pyrolysis33, and the yield of bio-oil and bio-gas increases94. Ani et al. investigated the temperature rise during microwave pyrolysis of oil palm shell using coconut-based activated carbon as a microwave absorbent with different adding ratios (0%, 25%, 50%, and 75%) in a fixed bed reactor, and found that the amount of absorbents affected the temperature curve. At 50% absorbents, the highest bed temperature reached about 400 °C95. Given the low microwave absorption rate of biomass, pyrolysis reactions do not occur without absorbents, or biomass only undergoes some primary decomposition reaction to generate carbohydrates and their derivatives. In the presence of absorbents, these derivatives can be further transformed91. Using 25% absorbents, the highest bio-oil yield of approximately 21 wt.% can be achieved, which contained over 60% phenolic compounds96.

Catalysts applied to microwave pyrolysis of biomass

Whether under conventional heating or microwave heating conditions, the products (especially bio-oil) obtained from direct pyrolysis of biomass have poor quality and are difficult to be directly utilized. Catalysis is one of the most cost-effective means for improving product quality. Therefore, in this section, we will focus on catalysts applied in biomass microwave pyrolysis, which fall into two categories, i.e., catalysts without and with microwave absorption properties.

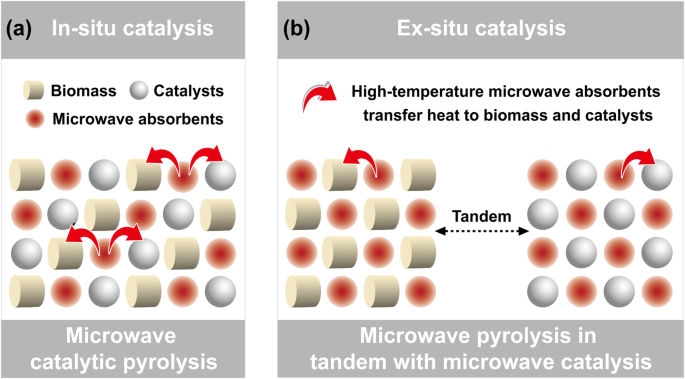

For catalysts without microwave absorption properties, two distinct scenarios based on catalytic modes of in-situ and ex-situ catalysis exist (Fig. 6). In the in-situ catalytic mode, due to the uniform mixing of biomass and catalysts, the heat driving the catalytic reaction can also come from the absorbents added in the pyrolysis reaction system. Biomass and catalysts, as weak- or non-dielectric materials, can be relatively evenly allocated with heat transferred by absorbents, as long as the three components are uniformly mixed (Fig. 6a). Suriapparao et al. mixed biomass, ZSM-5 catalyst, and char absorbent for microwave-assisted in-situ catalytic pyrolysis reaction. Char, as an absorbent, provided heat to biomass and catalysts simultaneously with a heating rate of 50-60 °C/min to drive pyrolysis and catalysis reactions, achieving product yields comparable to those under fast or even flash pyrolysis conditions. The primary pyrolysis products were effectively deoxygenated under catalytic action, enhancing the physicochemical properties of the pyrolysis oil97. The authors also found similar results when graphite absorbent, KOH catalyst, and biomass were mixed for microwave in-situ catalytic pyrolysis reaction98.

a In situ catalysis. b Ex situ catalysis.

In the ex-situ catalytic mode, biomass and catalysts are placed separately. Biomass undergoes thermal decomposition with the help of heat transferred from absorbents. An interesting extension of this approach is introducing absorbents in the catalytic bed under microwave irradiation. This corresponds to the construction of a two-stage microwave reaction system in tandem, i.e., a primary microwave pyrolysis system followed by a secondary microwave catalytic system (Fig. 6b). Wang et al. used SiC particles as an absorbent to assist in the thermal decomposition of soybean soapstock in the front-end pyrolysis bed, and mixed SiC powder into ZSM-5 in the back-end catalytic bed to assist in promoting the secondary catalytic upgrading reaction99. The authors also explored fixing ZSM-5 on the foam SiC absorbent with three-dimensional network structure in the secondary microwave catalytic system for more efficient heat transfer100.

For catalysts with inherent microwave absorption properties, they are not limited to specific catalytic modes and can even serve as absorbents. No additional absorbents need to be added to the reaction system, saving production cost. This type of catalysts is typically represented by activated carbon among carbon-based materials. As an absorbent, it can convert microwave energy into heat and transfer to biomass, triggering the thermal decomposition reaction of biomass. Furthermore, polar molecules in biomass can be absorbed by activated carbon, and under the action of electromagnetic fields, these polar molecules undergo violent motion and collision, generating heat to promote pyrolysis reactions33. The abundant porosity and retained functional groups in activated carbon make significant contributions to its catalytic activity101. As the ratio of activated carbon to Douglas fir increased from 1.32 to 4, the production of volatile components (liquid and gas) increased from 65% to 88.7%. When Douglas fir underwent direct microwave pyrolysis, the phenolic content was less than 1 wt.%. When activated carbon was added, the phenolic content significantly increased to 34-39 wt.%102. The high volatility yield and phenolic content are attributed to the combined effect of activated carbon as both a microwave absorbent and a catalyst. The main function of microwave absorbents is to increase the heating rate, thereby reducing the generation of char and promoting the generation of lignin derivatives (mainly phenols)103. In addition, the presence of a large number of carbonyl groups in activated carbon further accelerates O-CH3 homolysis to form phenols102. It was also reported that activated carbon under microwave radiation can also promote demethylation, decarboxylation, and dehydration reactions to enrich phenols102. For carbon materials such as graphite and char, they are mainly used as an absorbent to increase the heating rate, but their catalytic effects have not been extensively reported33.

Enhanced microwave discharge (microplasma) and hotspot effects can be obtained by loading metals on carbon materials104. Yan et al. conducted microwave heating experiments on rice husk char (RHC) and Ni loaded rice husk char (RHC-Ni). Some interesting experimental phenomena have been observed. After microwave was started, sparks randomly appeared on the RHC. This phenomenon was particularly intense in the most initial stage of the run. As the RHC temperature increased, the spark phenomenon gradually diminished. Afterward, some bright red spots (hotspots) appeared, leading to uneven heating. But once microwave was stopped, hotspots disappeared immediately, no matter how high the current temperature was. This also proved that hotspots were microwave-induced rather than temperature-related. When RHC-Ni was used as the reactor filler, the spark phenomenon became stronger. These sparks were generated by some electrons, indicating that the impregnation of nickel on biochar could increase the conductivity of absorbent and lead to stronger microplasmas. Higher microwave power could inspire stronger induced currents, as a result higher heating rate and more plasma was obtained104. It is worth mentioning that these microplasmas and hotspots could promote heterogeneous catalytic reactions105. On the one hand, the intensive energy carried by random and instantaneous microplasmas and the excited radicals brought by these plasmas were beneficial to break bonds in biomass molecules. The great amount of high-energy free electrons could also promote endothermic chemical reactions106,107. Wang et al. found that microwave-induced metal discharges resulted in toluene (as a model compound for biomass tar) degradation rate of more than 50%, whereas there was almost no degradation of tar without metal. When more discharge points were given, the toluene decomposition rate was higher. Microwave metal discharge outperformed conventional heating for toluene pyrolysis in terms of both the cracking efficiency and time required. A possible mechanism speculated by authors is as follows. Under microwave irradiation, there are partial explosions of the equipotential surface density and electric field strength along the curvature of the iron tip, and the N atoms in the gas near the tip and edge of the iron are excited by the strong electric field, inducing electronic transition, as well as accompanied by photon generation and discharge. The resultant strong luminescence (especially of ultraviolet light) and inevitable energy release directly cause chemical or photo-catalytic effects108. On the other hand, the temperature difference caused by hotspots would contribute to the better transfer of products, which pushed the reaction equilibrium in a positive direction109. The temperature difference may exist in the following three cases: (1) The catalyst particle temperature and/or catalyst support temperature are different from the reactant temperature. (2) The catalyst particle temperature is different from the catalyst support temperature. (3) The temperature of the spatial hotspots within the catalyst bed is different from the average temperature of the catalyst bed110.

The rich pore structure of carbon materials provides an effective specific surface area, which is also conducive to the full contact between the adsorbed macromolecular tar and the metal active sites of carbon materials surface for conversion into syngas33. Currently, monometallic Fe, Ni, or Cu111,112,113 and bimetallic Fe-Ni114, Ni-Ce115, or Ni-Cu116 have been reported to be loaded on carbon materials. The addition of bimetallic has a better effect on promoting gasification than that of single metals. Huang et al. studied the catalytic cracking of biomass tar by Aspen wood char loaded with metals (including Ni, Cu, or bimetallic Ni-Cu) and found that compared with single metal catalysts, bimetallic catalyst produced more H2 and CO at the same reaction temperature116. In addition, duplex metals play an important role in improving the coking resistance and stability of the overall catalyst. The reaction between Fe and surface carbon forms iron oxides, which helps to reduce the deposition of coke and improves the stability of Ni-Fe catalyst through the cyclic reaction of Fe2+O/Fe114. The introduction of Ce enhances the catalytic activity of Ni and promotes the dispersion of Ni for preventing sintering. When using Ce-Ni activated rice husk char, the highest conversion rate of toluene (as a model compound for biomass tar) was 100%, and the highest hydrogen yield was 28.2 vol%. After continuous use for 8 hours, the conversion rate of toluene was still greater than 90%115. Ni-Cu aspen wood char has also been found to have great resistance to sintering and carbon deposition, and catalytic stability116.

Zeolites are typically constructed by vertex (an oxygen atom)-sharing of TO4 (T for Si and Al) tetrahedron, as an important class of crystalline materials with abundant pores, tunable acidities (including concentration and strength), and great thermal/hydrothermal stability117, which are widely applied in the fields of catalysis, separation, ion exchange, gas storage, and sensing118,119,120,121. Si atoms in SiO4 tetrahedron can be replaced by Al atoms (or other trivalent metal atoms such as Ga and Fe). Due to the lack of electrovalence neutralization of O atoms, resulting in negative charges to zeolite framework. In this case, counterions are necessary to stabilize the zeolite framework and make it electrically neutral122. The roles of zeolite counterions are generally played by protons or extra-framework cations (typically alkali or alkaline earth metal ions such as Na+, K+, Li+, and Ca2+, Mg2+, Sr2+, Ba2+), leading to the construction of Brønsted acid sites in zeolites123,124. Brønsted acid sites are a typical class of catalytic sites associated with zeolite framework. Concentration and strength of Brønsted acid sites in zeolites greatly affect their catalytic properties, which can be modulated by varying the amount and type of incorporated atoms, respectively124. For instance, Brønsted acid strength decreases sequentially in Al-ZSM-22, Ga-ZSM-22, and Fe-ZSM-22125.

Microwave heating of zeolite is achieved through two mechanisms: dipole polarization and ionic conduction126,127. At the early stage of microwave heating of zeolite, the water adsorbed and the surface hydroxyl groups (≡SiOH, -Al(OH)-, etc.) can interact with microwave through dipole polarization, allowing heat flow from the surface into the interior of the materials128,129,130. Water molecules with ε′ as high as 78.3 (at 25 °C) are able to strongly absorb microwave and contribute significantly to the initial heating of zeolites130. Furthermore, when the density of surface hydroxyl groups is higher, the dielectric properties of zeolites become higher128. When zeolites are dehydrated, ionic conduction produced from the migration of exchangeable cations between different exchange sites along the channels and cavities of the zeolite framework according to an ion-hopping mechanism is the main contribution to microwave heating131. Cations are distributed between different sites of zeolite framework to maximize interactions with framework O atoms and minimize cation-cation electrostatic repulsions132. There is a potential barrier between the equilibrium positions, which the cations needs to cross when jumping from one site to another. If the external oscillatory electromagnetic energy can continuously increase the vibrational energy of the labile cations, the kinetics of a jump will be accelerated. During the resonance process, microwave energy will continuously dissipate in the form of heat along the decaying path of cations133. Whittington and Milestone found that in the 13X zeolites, the oscillation and collisions of mobile extra-framework cations with the alternating electric field are particularly frequent due to the large number of Na+ occupying sites within super cages that make up the structure, leading to rapid dielectric heating134. Santamaría et al. also found that as temperature increased, the motion of Na+ increased and the loss factor increased exponentially135. Na+ selective heating is supported by molecular dynamics simulations. Na is heated to greater temperatures relative to framework atoms (Si, Al, O) in the microwave fields due to the relatively greater mobility of Na+ ions136. The steric hindrance effect (related to size of cations and zeolite channels), electrostatic interactions (including coulombic attraction between cations and zeolite framework with negative charges and coulombic repulsion between cations and cations surrounding them, related to nature of cations) affect jump number and mobility of cations in zeolite framework, and therefore influence the overall electrical conductivity137. An interesting report showed that the coordinating effect of water molecules on cations can contribute to cation migration by weakening the interaction between cations and negatively charged zeolite framework123. In addition to the type of cations (especially their size and charge), the effect of cation concentration (depending on their charge and the Si/Al ratio of zeolite) on the mobility cannot be neglected138. Compared to monovalent cations, divalent cations (such as Ca2+) reduce the number of cations and the need of occupying unstable sites, thereby reducing their dielectric heating133. Nigar et al. compared the microwave heating ability of Y zeolites with different Si/Al ratios. They found that Y zeolites with Si/Al of 100 allowed more Na+ exchange, resulting in a more efficient dielectric heating, and Y zeolites with Si/Al of 780 had almost no mobile cations, which led to their microwave heating temperatures being much lower than those of NaY138.

Microwave can accelerate the kinetics of most chemical reactions due to thermal effects. Hotspots/superheating and selective heating can be classified as microwave-specific thermal effects139. Catalysts absorb electromagnetic waves to generate hotspots, leading to high temperatures (up to 1200 °C140) in a short time, capable of accelerating rate of the target reaction. However, high temperatures can synchronously promote the kinetics of the side reactions, intensifying the competition between the side reactions and the target reaction, leading to a decrease in the selectivity of the target products. The following examples demonstrate the two-facedness of microwave hotspots in catalytic reactions, further emphasizing the importance of hotspot control in microwave chemistry. Abdelsayed et al. found that the dangling OH groups (-Al(OH)-) of the Bronsted acid sites in ZSM-5 became hotspots due to the interaction with microwave through dipole polarization. These hotspots could not only dehydrogenate methane to carbon and hydrogen via microwave-assisted acid-catalyzed reactions, but also activate methane into CHX and enhance the C-C coupling into aromatic compounds via free radical reaction mechanisms128. Hu et al. showed that micro-scale “hotspots” formed by microwave dielectric heating of surface cations of ZSM-5 resulted in the degradation of N-nitrosodimethylamine organic pollutants. As the Si/Al ratio of ZSM-5 decreased from 130 to 12.5, more micro-scale “hotspots” are formed with greater density of surface cations, leading to an increased degradation rate constant141. However, microwave can also promote dehydrogenation and dehydration reactions in zeolites with low Si/Al ratios to deactivate the catalysts rapidly128. As the Si/Al ratio of ZSM-5 was reduced from 55 to 23, more microwave hotspots facilitated dehydrogenation and polycondensation reactions, leading to an increase in the content and graphitization degree of coke. In addition, microwave can induce some dehydration reactions from adjacent two Si-Al(OH)-Si acid sites to form Si2-Al-O-Al-Si2 and H2O, causing framework changes of zeolite and loss of catalytic activity. In general, the selection of the appropriate Si/Al ratios in zeolite-based catalytic reactions is not only important as active catalytic sites, but also is an important factor to be considered in microwave chemistry. The coupling between zeolites and microwave energy is important and determines the overall product selectivity as well as catalyst deactivation.

A limited number of results have indicated that the non-thermal effect of microwave can facilitate catalytic reactions by reducing the reaction activation energy. Hu et al. found that the activation energy for microwave-induced degradation of N-nitrosodimethylamine absorbed in ZSM-5 was estimated to be approximately 18.2 kJ/mol, which was much lower than that of typical thermal reactions (60–250 kJ/mol). They considered that this was a significant contribution of microwave non-thermal effect, but had not provided a clear explanation for the related mechanisms141. Kuhnen et al. explained the existence of non-thermal effects leading to microwave-enhanced reaction rates by the quantum tunneling effects. In the catalytic reactions, where proton exchange and proton-charge transfer play crucial roles, the effect of quantum tunneling on the proton exchange is significant, because the effective activation energy required by the proton transfer can be markedly reduced or even canceled by the high interaction energy of the proton with the electrical field during tunneling, thereby enhancing the overall rate of the reaction139.

Whether metal oxides can serve as absorbents depends on their dielectric properties, which are closely related to their crystal structure. Structural defects in the crystal can lead to increased dielectric loss142,143. For instance, MgO and MnO2 with structural defects have strong microwave absorption ability. Compared to direct microwave pyrolysis of food waste, their addition increased the average heating rate by 53.92% and 335.29% respectively, and increased the maximum temperature by 33.84% and 19.58% respectively. In contrast, the addition of weak microwave media, such as CaO, CuO, and Fe2O3, has a negative effect on the heating rate and maximum temperature144. Lo et al. also reported that during the microwave heating process of sugarcane bagasse, the addition of NiO, CuO, CaO, and MgO had little effect on the reaction temperature, but only slightly reduced the maximum temperature and heating rate. Among them, the content of CuO and CaO showed a moderate negative correlation with reaction temperature, while NiO and MgO showed a weak negative correlation145. Kuan et al. also found that the addition of these four metal oxides had little effect on the heating rate and maximum temperature during the microwave pyrolysis of corn stover. However, they suggested that a higher addition ratio may lead to adverse effects such as competition of microwave and energy absorption between metal oxides and corn stover146.

Metal oxides have been widely used in a variety of catalytic reactions due to their excellent activity, selectivity and stability147,148,149,150. There are transition and main-group metal oxides. Transition metal oxides are widely used in catalytic reactions such as oxidation, dehydrogenation, hydrogenation, polymerisation and synthesis due to the easily variable nature of metal ions. Main-group metal oxides including alkali metal oxides, alkaline earth metal oxides, alumina, and so on, have varying degrees of acidity and alkalinity and are catalytically active for ionic (e.g. carbonium ion) reactions. Interestingly, crystal defects closely related to the dielectric properties of metal oxides are often active sites for catalytic reactions151. Among them, oxygen vacancy defects are the most representative. As an important point defect, it can affect the local geometric and electronic structure of materials, generate unsaturated coordination sites, and thus form a large number of catalytic reaction active sites. By adjusting the adsorption free energy of catalytic intermediates, stabilizing these intermediates, reducing the activation energy of reaction determination steps, as well as weakening competitive reactions, the overall catalytic performance can be improved152,153. Tao et al. found that oxygen vacancy in NiO could adjust the electron density of the catalyst and promote the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural154. Sanjeev P. Maradur et al. reported that exposed 111 and 110 planes of CeO2 induced by the rod morphology had an important role in obtaining high oxygen vacancy in the material, and thus the catalyst exemplified an excellent catalytic activity (>95% conversion with >96% selectivity) during the carboxymethylation reaction of alcohols155. In addition, metal salts catalysts with microwave absorption properties have been explored in recent years, including Fe2(SO4)3, Na2HPO4, K3PO4, Na2CO3, MgCl2, AlCl3, CoCl2, and ZnCl2144,156,157,158. For example, in the process of biomass microwave pyrolysis, K3PO4 and Na2CO3 have been reported to play a positive role in increasing heating rate and maximum pyrolysis temperature, and improving the quality of bio-oil157,159.

Economic and environmental assessment of microwave catalytic pyrolysis of biomass

In order to evaluate the commercial potential of biomass microwave catalytic pyrolysis, energy analysis, TEA, and LCA were conducted, with a focus on examining the energy efficiency, economic feasibility, and environmental impacts of the technology involving microwave absorbents and catalysts. Energy efficiency can be evaluated in terms of net energy ratio (NER), which is defined by the equation: NER = Ei/Eo. Ei represents the total energy input, including the embodied energy of raw materials (Ei-1) and the electricity consumption for maintaining the overall process (Ei-2). Ei-1 is calculated as the product of the higher heating value and the mass of the raw materials. Ei-2 is measured by a power meter. Eo represents the total energy output, which is obtained as the product of the higher heating value and the mass of the different products17. In this review, one tonne of biomass (represented by pine wood) is selected as the object and suitable reaction temperature of 500 °C is chosen as the process conditions to investigate the relevant energy data as mentioned above. The specific results (including the data sources and the relevant calculation basis) are shown in Table 4.

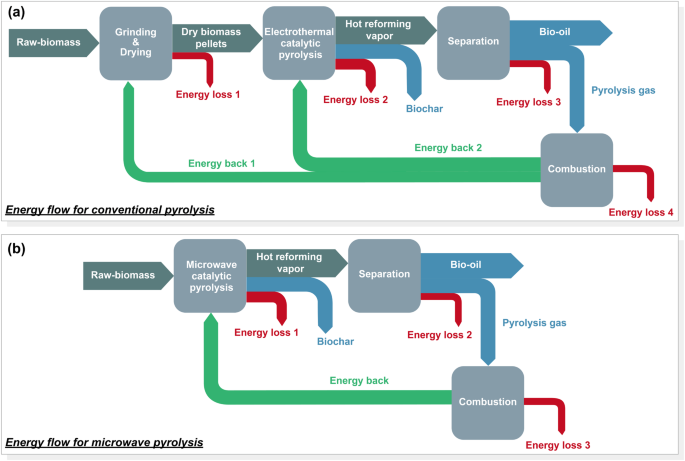

During conventional pyrolysis, the total energy output is lower than the total energy input due to the energy-intensive pretreatment (drying, grinding, etc.) steps. While microwave treatment may be able to avoid these energy-intensive steps due to its heating characteristics, the considerable energy losses in the conversion of electrical energy to microwave energy when driving the pyrolysis reaction, as well as the extremely low microwave absorption efficiency of biomass due to its poor dielectric properties, leading to a NER greater than 1 and even much higher than that of conventional heating. The overall energy efficiency of microwave heating depends on the microwave generation efficiency (i.e. from electricity to microwave irradiation) and the microwave absorption efficiency (i.e. from microwave irradiation to effective heat)160. The microwave generation efficiency depends on factors such as the quality, age, and operating temperature of the magnetrons161, and is generally 0.5–0.678, which indicates that nearly half of the electrical power will be lost in the process of generating microwave. The design and development of efficient magnetrons is critical to improving overall energy efficiency. Fedotov et al. designed a magnetron for microwave systems of heating, which has a frequency of 915 MHz, an output power of 3 kW, and an anode voltage of 4.5 kV. At a magnetic field of 140–160 mT, the overall efficiency of the magnetron is not less than 80%162. Additionally, Communications & Power Industries, a global manufacturer of electronic components and subsystems, developed a type of Industrial – CW Magnetron with the efficiency of 88%. The microwave frequency and power of this magnetron can be customized according to needs, and it is currently mainly applied in the field of food processing (https://www.cpii.com/product.cfm/11/55). Due to the poor dielectric properties, microwave absorption efficiency of biomass is low. During direct microwave pyrolysis, microwave energy will be mostly lost in the form of heat, which in turn increases the cooling load and reduces energy efficiency. The addition of microwave absorbents (e.g. SiC with a microwave absorption efficiency of up to 0.9160) can effectively convert microwave energy into thermal energy, thus reducing reaction energy consumption. If these improvements are combined with the appropriate introduction of catalysts, a NER of 0.97 will be obtained and a positive energy balance will be achieved (Table 4), which is expected to be tried on a larger scale (e.g., 100 tonnes biomass). It is worth mentioning that full and effective utilization of by-products contributes to further advancing the positive energy balance. It was reported that when pyrolysis gas was fully utilized, the energy efficiency of the system increased from 42.27 to 90.84%163. Huang et al. also pointed out that without the use of by-products and absorbents, the net energy balance of microwave system will be negative164. The energy flow of conventional pyrolysis and microwave pyrolysis of biomass is shown in Fig. 7.

a Conventional pyrolysis. b Microwave pyrolysis.

The two primary indicators of TEA are the production cost, including capital investment and operating cost, and the minimum selling price of the target products, essentially representing the balance between input and output. In terms of input, a significant portion of electricity cost in conventional pyrolysis is consumed in the drying and grinding steps165. In comparison, microwave pyrolysis is more inclusive of moisture and large particle size of biomass, saving energy-intensive pretreatment processes and reducing production cost. The electricity cost during microwave treatment comes mainly from pyrolysis process, which is closely related to the overall energy efficiency of microwave heating. It can be regarded as the product of two factors, the microwave generation efficiency and the microwave absorption efficiency160. The efficiency of conventional magnetrons is generally 0.5–0.678, and the microwave absorption efficiency of biomass is about 0.286,160,166, and thus the overall microwave heating efficiency is estimated to be 0.1. This means that only about 10% of electrical energy is converted into effective heat for pyrolysis reactions, resulting in extremely high electricity cost. The most direct and effective way to reduce the electricity cost is to use high-efficiency magnetrons (with an efficiency of over 80%), and to introduce microwave absorbents (such as SiC with a microwave absorption efficiency of 0.9), which can also be aided by a piece of data that direct microwave pyrolysis of biomass requires high power (1000-2000 W)167 and extended processing time, resulting in significant heat loss (over 40%) and low energy efficiency (below 40%)168. The addition of microwave absorbents allows biomass to reach pyrolysis temperature faster under the same microwave power input. However, the production and maintenance cost of high-efficiency magnetrons and microwave absorbents should also be considered.

In terms of output, the primary focus is on the huge liquid fuel market. The European Union has approximately 78 million tons of biomass used for biofuel production in 2020, almost doubling from 10 years ago169. The main goal of biomass pyrolysis should be to produce bio-oil with high yield and low oxygen content. Compared to conventional pyrolysis, the relatively low-temperature reaction chamber in the direct microwave pyrolysis system minimizes the opportunity for secondary cracking, allowing for the retention of a large number of easily degradable products. The introduction of microwave absorbents has to some extent increased the pyrolysis rate and temperature, further improving the yield of bio-oil. However, the oxygen content of the bio-oil produced through these pathways remains high, limiting its direct application as fuel and economic value. The most effective way to improve product economy is to use deoxygenation catalysts. Despite the associated production and maintenance costs, catalytic pathway has high economic potential due to the appreciable value of the resulting products. It was reported that the economic potential of catalytic pyrolysis route to produce bio-based aromatics was 1.5 times that of petroleum refining route14. During conventional pyrolysis, the solid product biochar is generally used as solid fuel (<$200/tonne) or soil amendment (< $400/tonne) of low economic value33. Under microwave conditions, the qualities of biochar, including surface area, pore structure, functional groups, and nutritional components, can be improved, enhancing its potential in advanced applications such as catalysts, adsorbents, and energy storage materials, with a potential value of up to $1000–15,000/tonne170,171. Pyrolysis gas can be well integrated into thermal system, serving as fuel for pre-treatment heating, such as biomass drying, to reduce energy input172.

From a lifecycle perspective, biomass is considered a zero-carbon energy source, as it fixes atmospheric carbon dioxide within the plant body during the growth process through photosynthesis. The environmental impact of biomass microwave catalytic pyrolysis primarily stems from three processes: (i) raw material supply (including collection and transportation), (ii) production (raw material pretreatment, and product conversion and upgrading), and (iii) final use of product. The most commonly reported indicator in LCA is the global warming potential expressed in CO2 equivalents.

The electricity consumption during the collection and transportation of raw materials increases greenhouse gas emissions. Ruan et al. proposed a distributed biomass microwave catalytic pyrolysis strategy, converting centralized processing plants into each distributed farm173. Due to the use of mobile and portable microwave pyrolysis equipment, light and fluffy biomass can be converted into high-energy density products such as bio-oil and biochar on site to reduce carbon emissions during collection and transportation processes.

Biomass pretreatment (crushing, grinding, and drying) contributes significantly to the global warming potential, with electricity consumption being the main factor affecting greenhouse gas emissions. The pretreatment process accounts for the majority of the total electricity consumption174, generating 1.5 tons of carbon dioxide for every ton of biofuel produced165. The use of microwave heating can partially reduce these steps, thus reducing carbon emissions. Compared to conventional pyrolysis, microwave pyrolysis requires additional electricity to start, and the energy loss during the conversion of electricity to microwave is quite high175. The poor microwave absorption of biomass can also lead to energy loss and increased electricity cost, thereby increasing carbon emissions. However, these defects can be mitigated by improving magnetron efficiency and introducing efficient absorbents. Even though conventional pyrolysis can be directly initiated by electricity, significant heat will loss due to poor thermal conductivity of biomass, which increases cooling loads and in turn increases carbon emissions. However, considering the greenhouse gas emissions during the production process of microwave absorbents (Table 5), it is critical to choose absorbents with low carbon emission intensity but strong heating capacity. Given the attractive negative global warming potential of biomass-based activated carbon and its role as one of the three major products, self-sufficient processes can be developed to minimize carbon emissions. The upgrading of bio-oil used for fuel production accounts for a significant proportion of greenhouse gas emissions throughout its lifecycle. Therefore, it should always be hoped that high-yield bio-oil with low oxygen content will be the main goal for achieving environmental benefits. The introduction of deoxygenation catalysts is crucial, but the carbon emissions during their production process should also be taken into account (Table 5). From this perspective, biomass-based activated carbon is also a good catalyst choice.

In the final use stage of the products, biomass-based fuels produced from both conventional pyrolysis and microwave pyrolysis have very low greenhouse gas emissions ranging from 9.2 to 38.9 g CO2-eq/MJ176,177,178, especially when compared to petroleum-based fuels (93.1 g CO2-eq/MJ of gasoline and 91.9 g CO2-eq/MJ of diesel)177. Approximately 80% of carbon in biochar is in a highly stable state in soil, playing a positive role in carbon sequestration179. Even though the overall environmental impact of biomass microwave catalytic pyrolysis has not been reported yet, there is no quantitative and comprehensive energy and economic data available on an industrial scale, but no matter what, this energy-economic-environmental analysis suggests that once commercialized, this technology has the potential to open up new paths for the bioenergy industry.

Scale-up challenges and potential solutions

Compared to conventional pyrolysis, microwave pyrolysis exhibits relatively prominent advantages in energy efficiency and product selectivity. However, biomass microwave catalytic pyrolysis technology is still in the development stage, and some scale-up challenges still need to be addressed before commercialization.

Accurate control of the heating rate and temperature

This challenge involves two aspects: precise temperature measurement and hotspots avoidance. Temperature measurement in microwave system is inherently challenging. Thermocouples, while capable of measuring the temperature inside the reactor, interact with microwave and introduce errors. Moreover, measurement during intermittent microwave operation breaks is not applicable to continuous process. Fiber optics are also used for internal temperature measurement using the fluorescence principle, unaffected by electromagnetic wave. However, the reproducibility of its results decreases with the increase of temperature, limiting their use to medium- and low-temperature reactors (<300 °C). External temperature measurement, represented by the use of infrared sensors, is also inaccurate due to temperature differences. A combination of internal and external temperature measurement methods is recommended to better capture and predict the overall temperature. The use of computer-based modelings to obtain the relevant process parameters such as maximum temperature and hotspots is a widely employed and relatively mature solution. Currently, various numerical techniques such as finite difference time domain method180, finite element method181 and finite volume method182 have been used to solve the governing equations (involving the electromagnetic equation or Maxwell’s equation and the heat transfer equation183) to obtain temperature distribution in the reactor. Predicted results include the temperature profile, the maximum temperature and the heating rate33. There is already commercially available software for temperature prediction during microwave pyrolysis of biomass, such as COMSOL (a finite element analysis software)181 and Ansys cfx (a finite volume commercial software)182. In addition, a unique ultrasonic temperature measurement technology is currently being developed184,185. Using the principle of the variation of soundwave velocity with the temperature of the propagating medium, the propagation time and the phase difference between the emitted and received ultrasound waves are used to calculate the sample temperature. As a non-contact type temperature measurement method, it has the potential to be applied in microwave processing in the future.

Hotspot formation is common due to changes in biomass dielectric and thermochemical properties, focused electric fields, and uneven absorbent distribution. A well-designed reaction chamber can minimize and control hotspots, e.g. by increasing the size of the microwave chamber, increasing the microwave frequency, increasing the microwave input power (to increase the electric field density), using multiple microwave inputs, and using a stirrer186,187,188,189,190. For example, during microwave pyrolysis of oil palm shell using coconut activated carbon as microwave absorbent, the use of stirrer resulted in uniformity of surface and bed temperature188. With a stirrer speed of 100 rpm, the yield of bio-oil was improved to 28 wt.%, which contained a high phenol content of 85%. The introduction of carrier gas into the reactor also helps to distribute the heat evenly191. In addition, optimizing the size and load of absorbents has a good effect on mitigating hotspots. Large particles of absorbents may result in uneven mixing with biomass particles, leading to increased hotspots. Small particles of absorbents contribute to uniform heating due to the increased effective contact area with biomass particles. Low loading of absorbents increases hotspots and vice versa. A data also demonstrated that during microwave pyrolysis of oil palm empty fruit bunch pellets, a significant variation between surface and bed temperature at low coconut activated carbon loading was observed, but the variation got small at high coconut activated carbon loading96.

Energy efficiency issues in large-scale microwave processing of biomass

To improve the energy efficiency of microwave processing system, the first step is to enhance microwave utilization efficiency. Due to the poor dielectric properties, microwave absorption efficiency of biomass is low. High input power (1000-2000 W) is often required to increase the electric field density to induce microwave pyrolysis of the biomass167. Microwave energy will be mostly lost in the form of heat, thus leading to a low energy efficiency (below 40%)168. Microwave absorbents can facilitate the conversion of microwave energy to thermal energy and can induce fast pyrolysis of biomass at lower microwave power, thus improving the efficiency of energy conversion. The development of efficient absorbents is one of the most effective ways to improve microwave utilization efficiency. In recent years, efficient composite microwave absorbents that combine dielectric and magnetic loss properties have been developed. Magnetic materials such as CoFe2O4192, Fe3O4193, Fe194, Ni195, and FeCo alloy196 are introduced into porous carbon materials to synergistically improve microwave absorption capacity. Wang et al. innovated an efficient microwave absorbent in terms of composition and structural design. Co particles were embedded into hollow carbon polyhedra through steps such as carbonization and pyrolysis to form Co@C structure, which was coated by natural bio-based nanoporous carbon (NPC) derived from wheat flour to form a special layered structure (Co@C@NPC). Due to the layered porous structure, the enhanced interface polarization, conduction loss, multiple reflections and matching impedance, and the enhanced synergistic effect between dielectric and magnetic loss, the composite microwave absorbent showed excellent microwave absorption performance. Under the condition of similar microwave absorption performance, the additive amount of this composite absorbent was much lower than that of other reported bio-based absorbents197. Additionally, the use of electromagnetic design tools to enhance microwave power distribution inside the reactor, further combined with fluidized or rotary reactors to distribute microwave more evenly onto biomass particles, is essential to improve the overall microwave utilization efficiency.

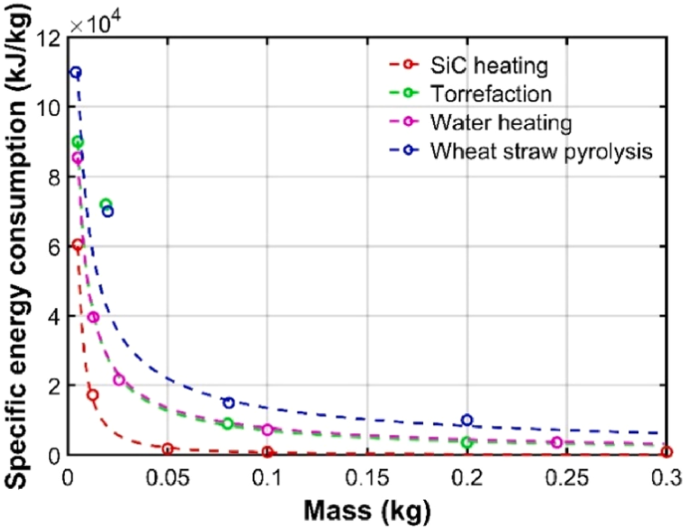

Considering the overall energy consumption during the processing process, efforts need to be made to actively integrate energy and take energy-saving measures. The efficiency of magnetrons is typically 50%, which means that half of the electrical energy will be lost in the process of generating microwave, greatly limiting the commercialization of microwave technology. The design and development of efficient magnetrons are the fundamental key to reducing system energy consumption. Currently, magnetrons with an efficiency of up to 88% have been developed (https://www.cpii.com/product.cfm/11/55). As estimated in the energy analysis in Section 4, a positive energy balance is expected if this type of magnetrons can be applied to the field of microwave pyrolysis of biomass. In addition, energy integration strategies, such as utilizing combustible gases generated during biomass processing to generate electricity for operating the microwave system, can be implemented. It was reported that when pyrolysis gas was fully utilized, the energy efficiency of the system increased from 42.27 to 90.84%163. It is also a feasible path to utilize renewable energy sources such as solar energy, wind energy, tidal energy, or biomass energy. Interestingly, there is a hyperbolic relationship between sample mass and specific energy consumption during microwave processing (Fig. 8)198,199. The specific energy consumption is lower at large sample mass than that at small sample mass, and large-scale microwave processing is strongly recommended to reduce energy consumption. Furthermore, compared to conventional heating, microwave heating can quickly attain the required temperature. Once the reaction begins, the power required to maintain the reaction is minimal, making continuous operation seemingly more advantageous.

Hyperbolic relationship between sample mass and specific energy consumption during microwave processing198,199.

Catalyst service life

Whether it is conventional catalytic pyrolysis or microwave catalytic pyrolysis, catalyst service life is an important aspect of large-scale potential assessment, as it to some extent determines the durability and economy of the process. Zeolites and metal oxides can maintain high catalytic activity after 5 cycles of use. Carbon based materials are low-cost and environmentally friendly, but their wear resistance and mechanical strength are far lower than those of zeolites and metal oxides. They cannot be regenerated through oxidative combustion, and can only maximize their durability during single cycle use. In this case, modification of carbon-based materials is necessary. The metal loaded on carbon-based materials can promote the gasification of tar or the in-situ combustion of coke, thereby enhancing the durability of carbon-based materials. Dai et al. reported that when using iron nanoparticles-based hydrochar to produce bio-based phenols, only partial decrease of catalytic performance was observed after 7 uses200. In addition, microwave is expected to mitigate catalyst coking through decarbonization reactions driven by “hotspots”. Wang et al. reported that the coke yield of HZSM-5 was lower during microwave heating compared to electric heating. They attributed this to the fact that the hotspots formed in the microwave field promoted the decarbonization reaction of carbon deposits with CO2 in the pyrolysis gas (C + CO2 = 2CO), which reduced the rate of catalyst deactivation100. Exploring the potential of microwave heating to reduce coke deposition is recommended for developing highly stable catalysts suitable for microwave systems in the future.

Scale-up of microwave reactors