A short review on green H2 production by aqueous phase reforming of biomass derivatives

Introduction

Hydrogen has attracted extensive attention as a sustainable secondary energy source in 21st century due to its high energy-density, multiple applications with no carbon footprint. The combustion heat of hydrogen (143 MJ/kg) is higher than fossil fuels such as gasoline (44 MJ/kg), natural gas (46 MJ/kg), and coal (29 MJ/kg)1. Notably, only water vapor is produced as hydrogen combustion product. However, the report from International Energy Agency (IEA) statistics shows that 95% of global hydrogen is produced from fossil fuels through steam reforming (SR), resulting in 70 million tons of carbon emission annually. Less than 5% of global hydrogen is produced through environmentally sustainable electrolysis methods2. Comparatively, biofuels is thought possible to replace up to 27% of the global transportation fuel by 2050, representing a significant contribution to sustainable energy solutions3. Given the scarcity of fossil fuels and the adverse environmental impact associated with their use, there is an unprecedented emphasis on the production of green hydrogen derived from renewable sources4,5.

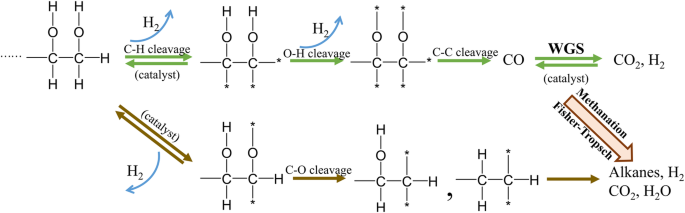

Compared to traditional technologies (e.g. SR, and autothermal reforming), aqueous phase reforming (APR) is an emerging technology for hydrogen production due to its lower reaction temperature and relatively higher technological efficiency (Table 1). Firstly, the APR uses subcritical water (100–250 °C) as the reaction medium, requiring lower energy consumption. Despite the lower hydrogen yield associated with APR, the much lower temperature contributes to a more energy-efficient process. Taking glycerol as an example, which is the most popular by-product in bio-diesel production, the APR is more feasible for hydrogen production than SR and AR ($0.055/kg vs. $0.110/kg)6. Compared to pyrolysis, APR of biomass derivatives can provide additional H2 through the water-gas shift (WGS) reaction7. Apart from some metal oxides (e.g., CeO2, TiO2, and ZrO2) and activated carbon (AC) as catalyst supports, lots of metal carbides and nitrides (e.g., Mo2C and MoN) show a poor stability at high temperatures8,9. APR process can also have a huge potential in fuel cells, which uses hydrogen, which requires low CO concentration. In addition, the source of feedstock of APR is wider than other technology (e.g., steam reforming and gasification) because of using water as reaction solvent, meaning feedstock for APR do not require dry pretreatment. Therefore, not only chemical compounds (alcohols and acids) but also high-water containing biomass and biowastes (e.g., food waste wastewater, sewage sludge, manure, microalgae, etc.) can also be processed. The mechanism of reforming hydrocarbons into hydrogen can be summarized into two steps (Fig. 1): breaking C-H bond down to generate part of produced H2, followed by cleavage of the C-C bond reacting with water molecule through water gas shift (WGS) to generate the rest of H2. In addition, part of C-O would also cleave to produce alcohols, acids, and alkanes, and then a part of by-products can undergo the above-mentioned reaction to produce H2. The earliest reported study of APR was performed by Cortright et al.10, using Pt/Al2O3 catalyst to convert biomass-derived oxygenated hydrocarbons into hydrogen at 240 °C. An ideal catalyst for APR should have high activity for C-C bond cleavage but low activity for C-O bond cleavage to promote the WGS reaction but inhibit the methanation and Fisher-Tropsch reaction. The Group VIII metals are commonly used as ideal catalysts for APR11. Generally, the noble-metal-based (e.g., Pt, Ru, and Pd) catalysts exhibit higher catalytic activity and better coke resistance than that of transition-metal-based catalysts (e.g., Ni, Mn, and Cu)12. Although Pt showed the highest catalytic activity in APR reaction, the density functional theory (DFT) indicated its low activity for C-C cleavage13. Therefore, to improve catalytic efficiency and reduce the cost, some inexpensive transition metals (e.g., Ni, Fe and Cu) have been added into Pt-based catalyst to improve its performance. The combinations of different bimetallic catalyst applied in APR have been summarized by López-Rodríguez et al.14. Compared with the conventional support such as active carbon and alumina, some oxides of rare earth elements (e.g., Ce and Ti) have attracted more attention due to their unique redox and acid-base properties15.

(Asterisk represents a surface metal site, modified from ref. 10).

Despite numerous reports in literature about effects of catalysts (e.g., metal-based and metal-free catalysts), reaction conditions (e.g., different temperatures and residence time), reactors (e.g., packed-bed, autoclave, and continuous-flow reactor)16, and feedstock (e.g., pure chemicals and actual biomass) on APR performance, recent innovations in active metal and support materials, along with their associated mechanisms, have not been comprehensively reviewed. Noteworthy advancements include synthesis of ultrafine nanowires17 and single-atom catalyst18 which have proven to be effective for enhancing the exposure of active metal sites, thus improving the APR activity. In addition, support materials for APR catalysts have also garnered increasing attention, with a focus on varying structure, defect induction, element doping, and the development of sustainable support materials19. Therefore, this review aims to summarize these new progresses that can improve the catalyst’s performance in APR of biomass-derived feedstock to produce green H2 (Table 2).

Metal oxides supported catalysts

Polymetallic oxides supported catalysts

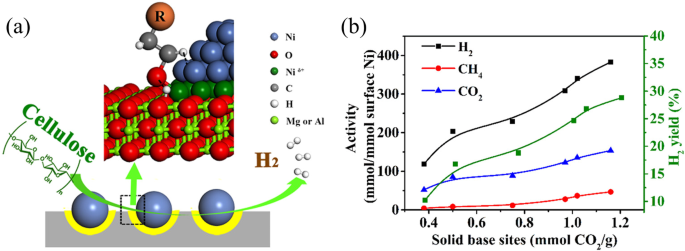

Aluminum oxide, recognized as a widely applied support, has been employed in various catalytic processes due to its high surface area, good thermal stability, and resistance to corrosion. The first reported study of APR used Al2O3 as the Pt catalyst support for H2 production from methanol10. Other metal oxides have been loaded with Pt for APR, whose activities were in the following order: Pt/MgO > Pt/Al2O3 > Pt/CeO2 > Pt/TiO2 > Pt/SiO213,20. In addition to noble Pt, some cheaper metals represented by Ni have also been selected as active metals because of their high activity for C-C bond cleavage21. Owing to the similarity in activation energy for C-O and C-C cleavage on Ni, the H2 selectivity of Ni is lower than Pt, while Ni catalysts are more selective toward alkane production. With Al2O3-MgO support, the dispersion of Ni particles can be enhanced thus improving the H2 selectivity (from 61% to 76%) and glycerol conversion (from 67% to 92%)22. Meanwhile, the Mg and Al can form the structure of layered double oxide (LDO) and layered double hydroxides (LDHs) through coprecipitation and calcination (700 °C 1 h) methods. With the help of more basic sites provided by LDO, the 19.5Ni/Mg3Al-LDO catalyst obtained a high turnover frequency (TOF) (99 molH2 molNi−1h−1) for APR of cellulose (Fig. 2)23.

(Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society).

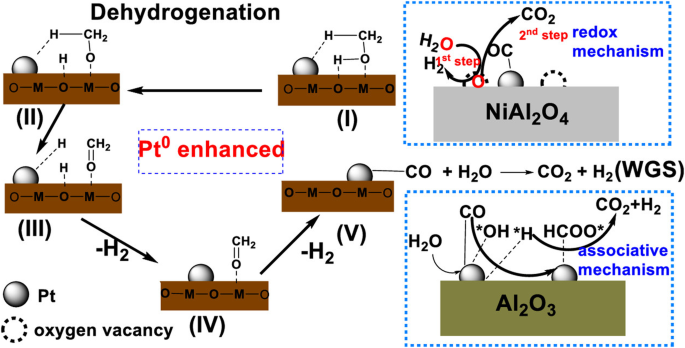

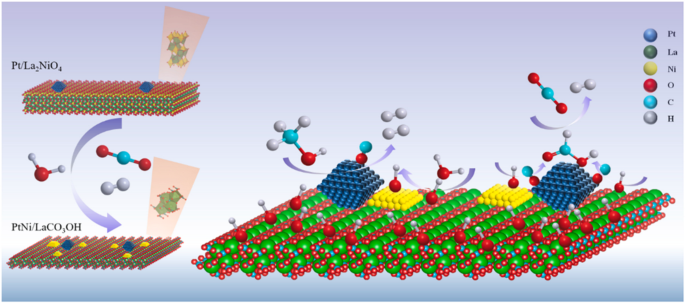

Active metal oxides have been constituted into the support. For instance, Ni oxide was mixed with alumina to produce spinel NiAl2O4 through coprecipitation method, and the Pt/NiAl2O4 catalyst led to a fourfold improvement in H2 yield compared with Pt/γ-Al2O3 through altering the WGS reaction pathways24. The higher oxygen vacancy allows the support to capture oxygen in H2O, facilitating dissociation of H2O to produce H2. In contrast, for γ-Al2O3, CO must react with H2O to form formates, which then decomposes into H2 and CO2. In other words, the former and the latter correspond to redox and associative reactions, respectively (Fig. 3). In addition to the spinel oxides, the perovskite oxides of ABO3 (A and B represents different metals), known for their structural versatility and thermal stability, have been explored as mixed oxide support for Pt catalyst, exhibiting improved performance in APR. More specifically, Mao et al. compared the activity and structural changes of different perovskite structures, and illustrated that the Pt/LaNiO3 could transform into Pt-NiOx/LaCO3OH during APR, leading to more exospore of Pt sites and O-H groups25. These sites are essential for the methanol dehydration and CO shift (Fig. 4). Through the addition of Ce into Pt/Al2O3 catalyst, the H2 yield can be increased from 37 to 56% for APR of glycerol26 and the WGS efficiency can be improved by 2 ~ 10 times27, which can be attributed to the high reactivity of Pt-O-Ce28. Moreover, through controlling of molar ratio of Ce and Zr in Al2O3, the Pt/Ce4Zr1-Al2O3 catalyst improved H2 yield by about 50% than the unmodified Al2O329. Similarly, Reynoso et al. investigated the effects of molar ratio of Co and Al for the support on the performance of APR catalyst, and found that the catalyst with Co/Al ratio of 0.625 obtained the highest H2 production rate (13.86 mmolH2gcat−1h−1) and glycerol conversion (88%)30. The improved catalyst performance can be attributed to higher oxygen vacancies and more adsorption of CO on Pt-interfered Co sites31. More importantly, Pt/CoAl2O4 also exhibited a better stability, maintaining over 95% glycerol conversion over 100 h of operation, whereas the monometallic oxide supported catalyst experienced a notable decrease in reactivity, dropping from 90% to less than 60%32. In addition, the Pt/LaCoO3 also exhibited the highest H2 production rate than other catalysts of Pt/LaMO3 (where M = Al, Cr, Mn, Fe, Ni)33.

(Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society).

Structure change of Pt/LaNiOx-2 during APR of methanol and schematic illustrations of mechanism of methanol APR, adapted with permission from25 (Copyright 2022 Elsevier).

Bimetallic catalysts on metal oxide supports

Bimetallic catalysts have proven to be effective for improving the catalyst performance with higher reactivity and better stability16,34,35. For instance, addition of copper (Cu) into Ni/Al2O3 can improve the H2 production rate from 180 to 353 mmol H2gcat−1 min−1 in APR of glycerol (Table 3)36. Similar synergistic effects were observed in adding Co, Fe, and Ce37,38 into a Ni-based catalyst. On the other hand, the noble metals of Pd, Rh, Re, Ru, Ir, and Cr have been added into a Pt/Al2O3 catalyst for APR of glycerol. Among them, the 5%Pt-1%Rh/Al2O3 achieved the highest H2 production rate (85,580 mmol H2gcat−1h−1) and selectivity (89%) in comparison to 5% Pt/ Al2O3 (42,625 mmolH2gcat−1h−1, 69.9% selectivity)39. Moreover, to enhance the catalyst economics, non-noble metals from VIII group (Fe, Co, Ni, and Cu) have also been doped into Pt/γ-Al2O3, and the Fe1Pt1/γ-Al2O3 catalyst exhibited the highest activity for APR of glycerol40. Generally, the positive impacts of doping active metals into a metal oxide catalyst could be attributed to the higher surface area, reactivity of surface oxygen atoms, and unique interaction between different metals.

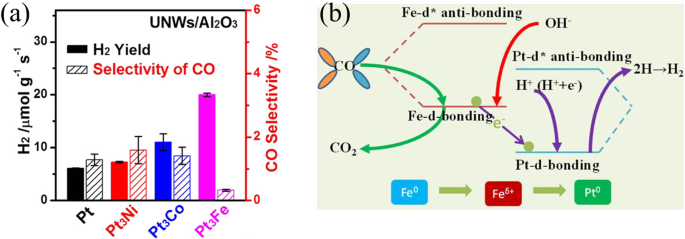

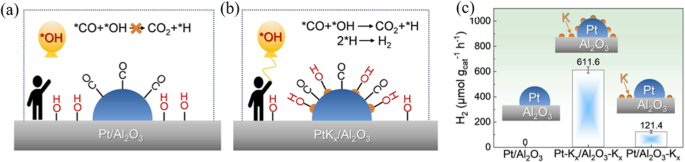

To get a higher exposure of active metal atoms, an ultrafine nanowires (UNWs) of Pt-based catalyst was developed for APR17. The Pt-Fe UNWs/Al2O3 obtained the highest H2 yield among other Pt-M catalysts in APR of methanol (Fig. 5a). The DFT analysis showed that the Fe site favors obtaining bonding electrons from *OH and *CO, corresponding to the association of CO and dissociation of H2O (green and red line in Fig. 5b). On the other hand, the dominant orbital level Pt bonding would be decreased by the formation of Pt4Fe, which facilitates charge exchange and formation of hydrogen H+ + H+ → H2 (purple line in Fig. 5b). The alkali metals (Na and K) enhance the dispersion of Au atoms and improve the amounts of –OH species, promoting the WGS reaction41. Consequently, K was added into Pt/LDO for APR of glycerol, and the glycerol conversion was improved from 27% to 83% with a constant H2 selectivity42. More specifically mechanism was revealed by Wang et al., which reported that K doping stabilize more *OH on the surface of Pt/Al2O3 catalyst. With the presence of more *OH, the reforming of *CO intermediate on Pt nanoparticles (Fig. 6)43 and H2 generation at low temperature were all promoted.

a Hydrogen yield and carbon monoxide selectivity, b reaction mechanism.

a Pt/Al2O3; (b) Pt-Kx/Al2O3. Note: The balloon and man represent the *OH intermediates and the Pt active sites, respectively; (c) H2 generation rates of the Pt/Al2O3, Pt-Kx/Al2O3-Kx, and Pt/Al2O3-Kx catalysts.

Ceria supported catalysts

The use of cerium oxide (ceria) in catalysis has been substantially increased from less than 50 publications in 1995 to over 1000 in 2015 annually44. The foremost characteristic of cerium oxide as a catalyst support lies in its exceptional oxygen storage capacity (OSC) and oxygen mobility throughout the lattice41. The mutual conversion of Ce3+ and Ce4+ accompanies the storage and release of oxygen. In other words, the rate at which cerium undergoes Ce3+/Ce4+ redox cycles determines the quantity of oxygen vacancies, which benefits promoting the redox reaction in WGS. More specifically, relevant DFT shows that the formation of oxygen vacancies on the CeO2 surface concurrently enhances both the acidity and basicity of Lewis pairs (FLP). This dual modulation lowers the energy barrier for chemical bond cleavage, specifically facilitating the heterolytic cleavage of H2 through augmented acidity and basicity on FLP sites45.

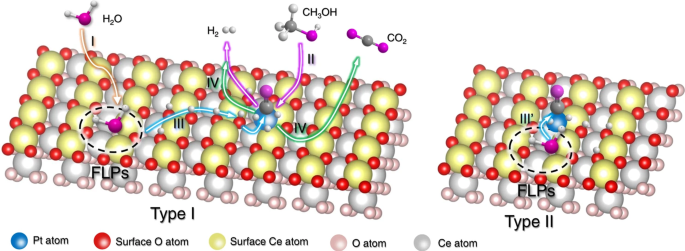

Some recent advances in modifications of CeO2-supported catalysts for APR are given in Table 4. Ceria can be divided into different morphological structures such as nano-rods, nano-particle, nano-octahedra, and nano-cube, depending on the operating conditions in their formation46. The structure of nano-rod is considered more ideal due to its crystal planes {110} and {100}, which are more reactive for CO oxidation than {111}. Li et al. has synthesized s structure of porous ceria nano-rod through reducing pressure during formation of percussor, which can improve dramatically higher OSC (identified by O2-TPD) from 167 to 900 μmolO2 gCeO2−1 47. The reduced pressure (using glass bottle rather than autoclave for synthesis of ceria precursor) would be beneficial for keeping part of Ce(OH)3 in CeO2 precursor nano-rod, and these Ce(OH)3 would be converted into CeO2 in second-step of hydrothermal treatment, leaving some holes on the surface of CeO2 nano-rods. In presence of oxygen vacancies (identified by XPS), the TOF of Pt/porous nano-rod (497 molH2 molPt−1h−1) could be one fold higher than that of regular-rod (256 molH2 molPt−1h−1) for APR of methanol48. This porous nano-rod can be loaded with Pt using a UV-induced method, producing a single-atom Pt catalyst (identified by X-ray absorption near edge structures, XANES) which has the highest reported TOF (1,103 molH2molPt−1h−1) among other Pt/metal oxide catalysts. The DFT calculation showed that with the help of Lewis acidic Ce3+ sites and frustrated FLP of Pt dual active sites, the energy barrier of methanol dissociation can be decreased to 0.23 eV (Type I, Fig. 7). Meanwhile, the UV photo-deposition method is beneficial for the chloride (Cl–) removal during loading Pt into CeO2, resulting in activation of the surface oxygen. This activated surface oxygen, in turn, promotes the dissociation of H2O and the oxidation of CO through an associative mechanism49. The dissociated *H and *OH would be transited from FLP sites of CeO2 to single-atom Pt sites, and then reform into extra H2 and CO2 (Type II, Fig. 7).

The proposed catalytic pathway for APR on the Pt1/porous CeO2, adapted from48, (Copyright 2022 Springer).

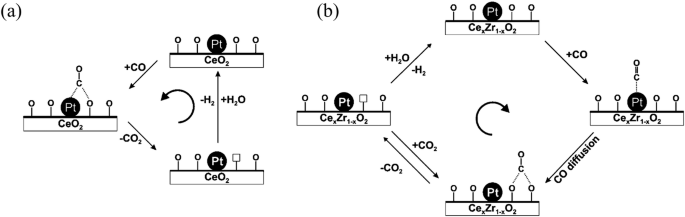

Doping heteroatoms into CeO2 is also an effective method to modify the crystal lattice and improve the oxygen vacancies. For instance, doping Zr into CeO2 could increase the H2 yield from 7.3% (pure CeO2) to 40.9% (25%Ce-Zr oxide) higher than that of pure ZrO2 (16.3%)15. Same trends have also been observed for other feedstocks, such as ethylene glycol and glycerol50,51,52. The positive impact of Zr doping can be succinctly summarized as: Zr4+ can decrease reduction energy of transformation from Ce4+ to Ce3+, thus increasing the concentration of defect Ce3+ sites53. Concurrently, the Zr4+ changes the structure of Pt/CeO2 and creates more oxygen vacancies. With the help of oxygen vacancies, the diffusion of *CO from Pt site to O sites is facilitated and extra H2 is formed due to deprivation of O from H2O (Fig. 8b). In fact, doping divalent metals into CeO2 can almost generate a higher concentration of oxygen vacancies. Doping Cu and Ni has garnered significant attention in APR and WGS due to their distinctive interactions with Ce atoms35,54,55. In the case of copper, the formation of Cu+–Ov–Ce3+(Ov means oxygen vacancies) sites involves a superior active site compared with the regular Ce-O bond. With the help of this active sites, the CO adsorption and H2O dissociation can occur simultaneously without disturbing each other in low temperature WGS56,57. Intriguingly, Ni doping exhibits a distinct behavior wherein Ni does not actively participate in the catalytic reaction. Instead, it serves as a single-atom promoter, enhancing the generation of oxygen vacancies and exposing individual cerium atom sites58. In addition, the 1Ni-4Cu/CeO2 led to a higher H2 production rate than that of monometallic catalyst (Ni or Cu)59, indicating the synergistic enhancement of ceria-supported Ni-Catalysts.

a On Pt/CeO2, b on Pt/CexZr1−xO2, adapted with permission from ref. 53 (Copyright 2012 Elsevier).

Carbon-based supported catalysts

Molybdenum carbon supported catalyst

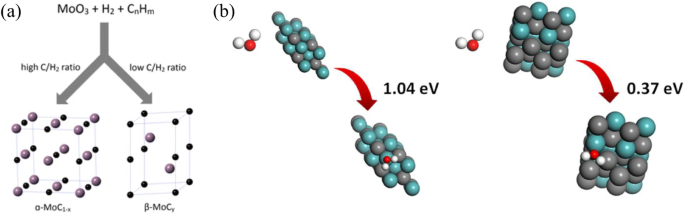

Transition metal carbides have emerged as promising catalyst support for H2 production, due to their significantly enhanced activity in hydrogen and oxygen adsorption, exhibiting certain platinum-like characteristics60,61. Molybdenum carbide (Mo2C) has shown superior efficacy in activating H2O and reforming hydrocarbons at low temperatures compared to other transition metal carbides (e.g., tungsten carbide and titanium carbide)62,63. The pioneering use of Mo2C as catalyst support for WGS reaction revealed a reactivity comparable to that of the commercial Cu–Zn–Al catalyst64. Subsequent investigations revealed that by changing the carburizing gas and reduction gas, the MoxC could form two distinct structures, (Fig. 9), namely α-MoC (hexagonal close-packed) and β-Mo2C (cubic close-packed), respectively65. Siyu et al. compared these two kinds of structure in WGS reaction, and the Au/α-MoC showed a dramatically higher reactivity than Au/β-Mo2C66. The improved activity could be due to the higher binding energy of α-MoC sites (1.04 eV) than that of β- Mo2C (0.37 eV), contributing to a much faster H2O adsorption and reforming67. Meanwhile, the DFT calculations also indicated that due to different Mo/C ratios on the MoxC surface, the HOCO intermediate preferably formed CO on C-rich α-MoC catalyst, whereas forming CH4 on β-Mo2C64. Therefore, the research regarding α-MoC catalysts attracted more attention and became increasingly in-depth due to its unique high reactivity.

a Structures of α-MoC and β-Mo2C; (b) H2O adsorption on the surfaces of α-MoC {111} facet and β-Mo2C {101} facet. The Cyan, gray, red and white balls represent Mo, C, N and H atoms respectively.

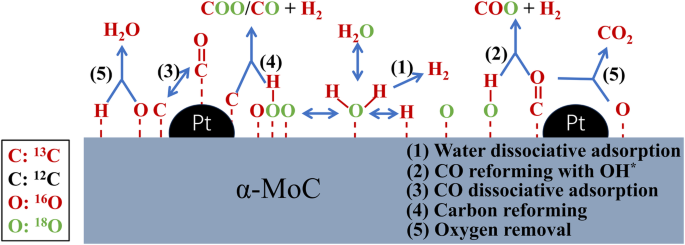

By far, the Pt1/α-MoC catalyst showed the highest H2 TOF of methanol APR among the existing catalysts, achieving an impressive 18,046 molH2molPt−1h−1 at 190 °C68. The atomically dispersed Pt on MoC (single-atom catalyst) can avoid the formation of Pt cluster, which only has a mild APR activity. On the other hand, the interaction of Pt and Mo can form more electron-rich regions, decreasing the energy barriers of methanol dissociation (from 1.30 eV on MoC to 0.67 eV on Pt1/α-MoC) and WGS reaction (from 1.87 eV on MoC to 0.91 eV on Pt1/α-MoC). Meanwhile, to improve the catalyst economy, some non-noble metals (Ni, Cu, and Co) were loaded on α-MoC. Remarkably, Ni/α-MoC exhibited outstanding activity, surpassing the Cu and Co catalysts by approximately fivefold (7.09 vs 1.81 and 1.40 μmolH2gcat−1s−1)69. Similar to Pt1/α-MoC, the energy barriers of methanol activation (0.73 vs 1.30 and 1.42 eV) and WGS (1.13 vs 1.6 eV) on Ni1/α-MoC {(111)} was much lower than that of α-MoC {111}and Ni {111}, respectively, indicating the excellent synergy over Ni1 − Cx motif constructed by atomically dispersed Ni with molybdenum-terminated α-MoC. While the single-atom MoC catalyst has the current highest H2 production effeminacy, the active metals on support surface would agglomerate during catalytic process, resulting in a rapid catalyst deactivation. Addressing this concern, a catalyst with co-existence of Pt atoms (Pt1) and Pt cluster (Ptn) was developed70, where it was observed that at the Pt loading of 2 wt%, the presence of Pt1 and Ptn could be detected simultaneously, while only Pt1 was observed at a low loading (0.02–0.2 wt%). Although 0.02 wt% Pt1/MoC has a higher H2 production rate, the 2 wt% (Pt1-Ptn)/MoC catalyst exhibited superior stability (remaining 56% activity) and ultimately produced 4,300,000 mol H2/mol Pt in 263 h, whereas Pt1/MoC lost nearly 95% activity within 10 h. The oxygen species on catalyst surface are beneficial for CO reforming, but the excess surface oxygen species can cause the oxidation and deactivation of Pt1/MoC catalyst. In contrast, the crowding surface Pt species (Pt1 and Ptn) are beneficial to clear the excess surface oxygen (routes 2 and 4 in Fig. 10). Notably, about 35% H2 is actually provided by the CO activation and successive reforming routes (routes 4 in Fig. 10 rather than WGS). This route can also be a reason for the exceptionally high H2 production activity of Pt1/MoC than other catalysts (Table 5). In addition, flame spray pyrolysis method was proposed to replace conventional high-temperature ammonification and carbonization process for a more environment-friendly synthesis of α-MoC, the produced Ru/α-MoC exhibited a higher WGS activity than Pt/α-MoC (212.7 vs 155.2 mmolH2gcat−1h−1)71.

Schematic of the reaction routes for the WGS reaction over Pt/α-MoC, modified from70.

Carbon supported catalyst

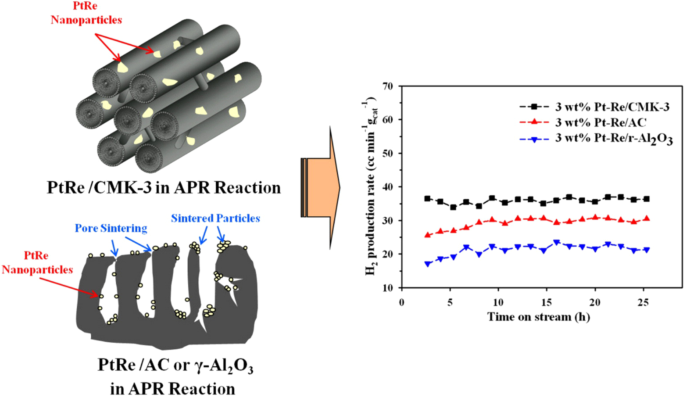

Other carbon supports include AC, single/multi-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNT/MWCNT), mesoporous carbon (MC), graphene oxide, carbon dots, and biochar. Research efforts concentrate on employing MWCNT and MC as catalyst supports. Their tunable pore structures contribute to heightened activity, improved stability, and enhanced structural operability, positioning them as superior choices compared to metal oxides and AC72. Specifically, mesoporous carbon (MC) exhibits a higher surface area (1,102 vs. 195 m2/g) compared to MWCNT, resulting in a superior H2 production rate (271.0 vs. 26.9 molH2molPt−1h−1) for APR of glycerol73,74. MC can be categorized into two-dimensional mesoporous carbon rod type-CMK-3, hollow types-CMK-5 and three-dimensional CMK-9 according to their structure. The pore structure of CMK-3 (Fig. 11) promotes the metal dispersion and sintering resistance, leading to a higher H2 production rate than that of AC or Al2O375. Compared with Pt/CMK-3, Pt/CMK-5 outperformed with a higher H2 yield (57.3 vs. 40.4 mLH2gcat−1 min−1), attributed to the open structure of the support and a more significant dispersion of Pt within Pt/CMK-576. Current investigations into MNCNT and mesoporous carbon-based catalysts primarily focus on the effects of composite metal, such as electronic effects related to interfacial charge distribution between the metal and carbon scaffold3.

The diagram structure and H2 production rate of PtRe catalyst on support of CMK-3, AC, and Al2O3, adapted with permission from75 (Copyright 2012 Elsevier).

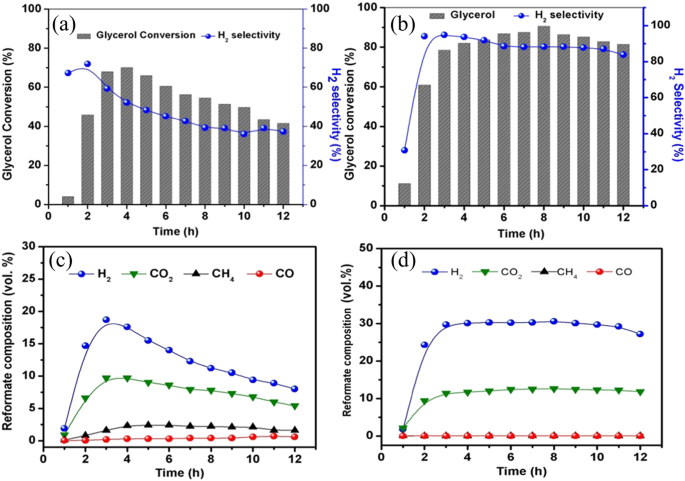

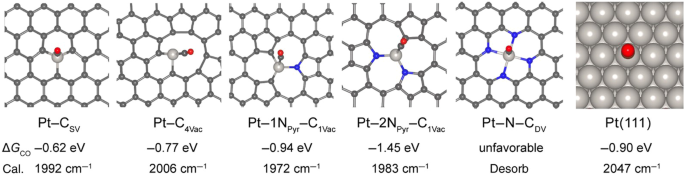

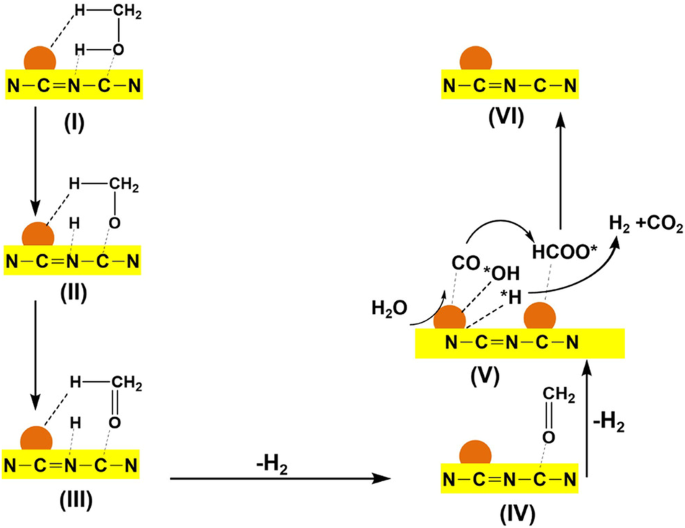

On the other hand, doping nitrogen into carbonaceous supports can be an effective method for surface functionalization. For example, through adding melamine as N source during the sol−gel process, the synthesized Pt-Ru/N-doped mesoporous carbons (NMC) obtained a higher glycerol conversion (from 70 to 90%) and H2 selectivity (from 18 to 30%) than the undoped MC (Fig. 12)77. The enhancement in activity can be attributed to the alkaline environment created by nitrogen doping, notably, the provision of three distinct basic adsorption sites: graphitic, pyridinic, and pyrrolic sites. Meanwhile, the N in carbon framework also serves as anchoring site for metal nanoparticles, inhibiting the metal sintering and enhancing the stability (Fig. 12). Similar improvement was also observed in doping N into Pt-Mn/platelet carbon nanofibers78 and Fe-Cu/ graphene79 for APR of ethylene glycol and methanol, respectively. More specific interaction between Pt and C-N was revealed by Kun et al. through the methods of electrochemical infrared (IR) spectroscopy and DFT calculations80. The lower CO adsorption strength of Pt–1NPyr–C1vac and Pt–2NPyr–C1vac than that of Pt-CSV (Fig. 13) indicates the enhanced CO adsorption capability. In addition, the Pt–NPyr–C site facilitates the direct interaction between CO* and H2O, bypassing the involvement of OH* dissociated from H2O, thus promoting the oxidation of CO. Notably, the composite of N-doped carbon dots (NCD) with g-C3N4 can serve as metal-free catalyst for APR of methanol, obtaining efficient H2 yield of 19.5 μmol g−1h−1 at temperatures as low as 80 °C81. The N in NCD is mainly in the form of pyrrolic N, which plays a crucial role in localizing surface charges and promoting adsorption and polarization activation of methanol. The beneficial effects of NCD mainly can be illustrated in Fig. 14 associated with steps I~IV. Analogously, graphene doped with N and boron (B) could also act as metal-free catalyst for APR of glycerol, yielding 20% molH2 molgly−1h−1 82. Moreover, chitosan, as nitrogen-containing reactant, can react with glucose (reducing sugar) through Milliard reaction to form stable cross-linking conjugate, exhibiting excellent reducibility and notable activities in the anti-oxidation. This composite N-carbon, doped with Cu for APR of methanol, achieved enhanced Cu dispersion and coexistence of Cu0/Cu+, promoting methanol dehydration and WGS, resulting in a H2 generation rate of 1.39 × 105 μmolH2gcat−1h−1 and 99.9% of H2 selectivity at 210 °C83.

a Glycerol conversion of 5% Ru/MC; (b) glycerol conversion of 5% Ru/ NMC-3; (c) reformate composition of 5% Ru/MC catalyst; (d) reformate composition of 5% Ru/NMC-3.

Simulated binding free energy and vibrational frequency of COL on the most stable Pt-based moieties, adapted from80 (Copyright 2021 Chinese Chemical Society).

The proposed reaction mechanism of the APR of methanol over N-doped carbon dots/g-C3N4, adapted with permission from ref. 81 (Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society).

Metal pincer complexes supported catalyst

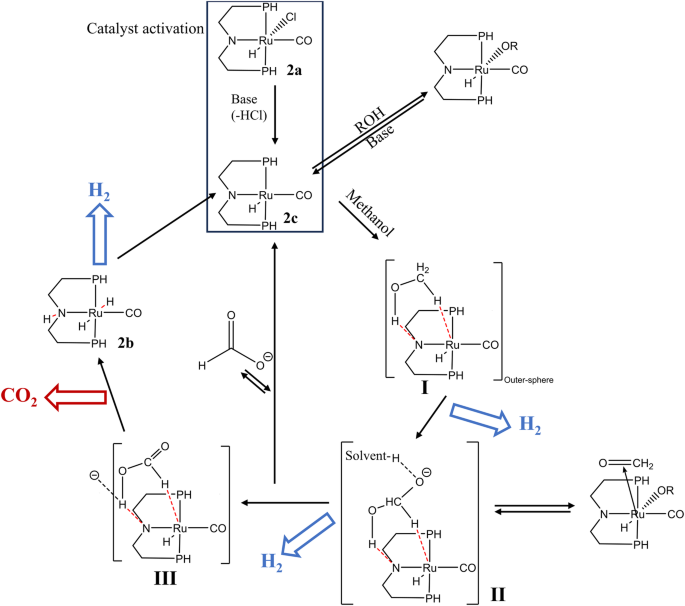

Metal pincer complexes are a significant class of organometallic compounds widely employed in catalytic reactions allowing for precise control over catalytic reactions, enhancing selectivity and efficiency in APR. Recently, metal pincer complexes were applied to the low temperature (<100 °C) APR of methanol, owing to its potential application in fuel cell (low level of contaminant gases CO < 10 p.p.m.) and significant stability due to the mild reaction condition. The PNP ruthenium-based pincer complexes, chelating organic structure ligand with atoms of phosphorus and nitrogen, have shown activity as high as 4719 molH2 molmetal−1h−1. As shown in Fig. 15, with the help of additional base, the 2a was converted into 2c, which can convert methanol into formaldehyde and the first part of H2 on the outer-sphere (I). Subsequently, the formate is formed by the combination of hydroxide, producing the second part of H2 (II). Finally, the catalyst has two possible paths at this stage: it can either initiate a new catalytic cycle by releasing formate and reacting with methanol, or it can execute the final step of the catalytic cycle through pathway III, resulting in the generation of CO2 and the third part of H2. Additionally, this optimized system is stable under aqueous alkaline conditions and remains active for more than 3 weeks84. While metal pincer complex-supported catalysts enable hydrogen production at lower temperatures, the requirement for the addition of a base constrains their development in the field. To enhance environmental friendliness and practical applicability, a series of Ru-PNP catalysts with similar structure but base-free catalyst were developed by Monney et al.85. Due to the lack of chloride ligand, such catalyst does not need the base activation (2a → 2c, Fig. 15) and can achieve TOF of 239 molH2molmetal−1 h−1 with the synergistic interaction between two catalysts (A1 and B1 in Table 6). Meanwhile, other structures of Ru-based, using hydroxypyridine86, bipyridine (PNN)87, and azadiene88 as ligands, have also proven to have activity for low-temperature APR of methanol. In addition, the N-heterocycles of bipyridonate also were combined as ligand to form Ir-based catalyst89. The obtained catalyst could operate under nearly mild conditions (0.05 mol NaOH concentration) with 89% H2 yield in 20 h, indicating another promising base-free APR catalyst. Considering catalyst economy, some non-noble metals have also been selected to replace the Ru active site in PNP catalyst, among them, Fe-based catalyst showed a higher TOF (702 vs. 32.6 molH2molmetal−1 h−1) than Mn-based catalyst90,91.

The proposed catalytic cycle for PNP ruthenium-based pincer complexes for APR of methanol, modified from84.

Conclusions and perspectives

The effects of catalysts and mainly their supports have direct impacts on APR of biomass derivatives for green H2 production. The incorporation of doping elements in mixed-metallic catalysts often led to increased activity and stability compared to monometallic catalysts, which can be attributed to a greater number of active sites, and enhanced capacity while preventing catalyst poisoning and structural deformation. Some elements (e.g., K, Ce, and N) don’t have activity themselves, but can serve as promoters, enhancing oxygen storage capacity and modifying structure of support. Remarkably, with help of N-doping, carbon dots can serve as cost-effective metal-free catalysts. Inducing more defects and pores in the structure of support is beneficial for promoting exposure of active sites. The superior activity of MC compared to AC and MWCNT can be attributed to its porous structure, which can provide more space for active sites. Through changing the template, MCs with different structures, namely CMK-3, CMK-5 and 3D CMK-9 can be synthesized and show a better performance. Similarly, the porous ceria which was synthesized by pressure-reduced two-step hydrothermal method, also has the superior activity for H2 generation due to its porous structure and more presence of defects. Some other methods, such as chemical etching and plasma treatment92, have potential for inducing defects, thus modifying the support structure into more favorable transport of the reactants and products. The single-atom catalysts represented by Pt1-MoC exhibit a significant higher activity owing to their high atomic utilization and lower activation energy compared with conventional catalysts. However, the tendency to form active metals cluster should be retarded to improve stability of single-atomic catalysts. The method to incorporate other element into support and strengthen the interaction between active metal and support, can be one of the future development directions.

Considering the environmental impacts, more base-free catalyst should be developed to prevent post wastewater treatment. Meanwhile, some catalyst synthesis processes involve use of some toxic substances (e.g., organic metal salts and N/P-heterocycles), which should be replaced by less-harmful substances. Furthermore, some biomass materials can also be precursors for catalyst support, such as 3D-hydrochar derived from sawdust shows a good stability and H2 production93. Meanwhile, these biomass-derived biochar can foster carbon sequestration from atmosphere, indicating environmental benefits94. Generally, the forthcoming research directions should prioritize the advancement of catalytic systems, focusing on augmenting efficiency, stability and environmental friendliness, and attaining a more comprehensive comprehension of the reaction mechanisms.

Responses