Implementation of trauma and disaster mental health awareness training in Puerto Rico

Post-disaster interventions and best practice guidelines

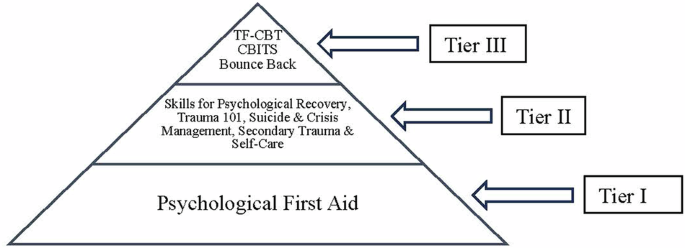

Post-disaster mental health intervention efforts have been grouped into three phases (immediate aftermath of the disaster, short-term recovery and rebuilding, and long-term recovery), depending on the timing of the event and the unique needs of the population in each phase (see Fig. 1).

TFCBT Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, CBITS Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools.

Tier I intervention: immediate aftermath of a disaster

In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, restoring access to basic needs (e.g., food, water, clothing, medical attention, shelter), promoting a sense of safety and security, and reconnecting loved ones should be the number one priority of any intervention. Offering practical assistance and basic coping skills to help bolster resiliency and help mitigate potential long-term negative sequelae that can later interfere with adaptive functioning and natural recovery is the primary focus17.

Psychological First Aid (PFA) is an evidence-informed, culturally and developmentally sensitive intervention developed by disaster mental health experts aimed at providing practical assistance and promoting a sense of safety, security, calm, connectedness, hope, and self and community efficacy to survivors after a disaster18,19. PFA is designed to reduce the initial distress caused by a disaster and to foster adaptive functioning and coping strategies both in the short and long term among adults and children. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN)/National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD) PFA model18 is comprised of eight core actions: (a) Contact and Engagement, (b) Safety and Comfort, (c) Stabilization, (d) Information Gathering, (e) Practical Assistance, (f) Connection with Social Supports, (g) Information on Coping, and (h) Linkage with Collaborative Services. Each core action is selected and delivered based on the unique needs the survivors identify during the initial contact. It is flexible in that it can be delivered in just one meeting (ranging anywhere from a few minutes to a couple of hours) or over multiple contacts, individually or as a group, in a wide range of settings (e.g., shelters, schools, and hospitals), via lay providers (e.g., first responders) or by mental health professionals as part of a coordinated disaster effort response.

Tier II interventions: short-term recovery and rebuilding phase

During the short-term recovery and rebuilding phase (months to a year after a disaster), tier II interventions provide more specialized child and adolescent trauma and grief interventions for those with moderate-to-severe persisting distress. These interventions can often be provided by paraprofessionals or community providers and can include psychoeducation about mental health topics and skills to cope with adversities (thereby increasing access to care given the often-limited availability of licensed mental health providers in underserved schools and communities).

Skills for Psychological Recovery (SPR)20 is a Tier II secondary prevention intervention model in that it provides a level of care that is more intensive than PFA but is not designed to address severe psychopathology. SPR is a brief, skills-based intervention, which can be delivered in one to five sessions depending on the survivor’s needs. It is designed to be delivered by mental health, other health workers (e.g., social workers, counselors, victim advocates), or paraprofessionals (e.g., disaster crisis counselors) who provide ongoing assistance and support to affected children and adults within a variety of settings, including schools, primary care clinics, faith-based organizations, homes, among others. Like PFA, SPR uses a modular approach so that providers can tailor the skills taught to the unique needs of the child, adolescent, adult, family, or group that they are working with. SPR is comprised of six core skills: (a) information gathering, (b) building problem-solving skills, (c) promoting positive activities, (d) managing reactions, (e) promoting helpful thinking, and (f) rebuilding healthy social connections.

Other survivors will benefit from psychoeducation workshops that provide basic information about what they may be experiencing after a disaster and brief tools or coping strategies. Examples of topics can include 1) Trauma Informed Care21, an introductory workshop that can be offered to community members, paraprofessionals, school staff, and anyone who cares for children and youth on what trauma is, how it impacts children’s brains, bodies, emotions, and behavior, and how one can identify the signs of trauma-related symptoms and help children cope and/or connect them with evidence-based services. The goal is to facilitate the creation of a “trauma-informed lens” through which those working with youth can view their behaviors and presenting concerns (e.g., “This child’s behavioral outbursts ‘make sense’ given their fight or flight response has been activated post-disaster. Here are some coping skills I can teach them to use to help them regulate in the classroom”); 2) Suicide and Crisis Management22 is an introductory workshop offered to a similar population as described above on the prevalence rates for youth suicide, safe and appropriate crisis de-escalation techniques, and how to identify suicidal risk and make a referral; and 3) Secondary Traumatic Stress and Self-Care23 is an introductory workshop offered to teachers, school staff, parents and providers who work with trauma-affected youth in identifying signs of secondary traumatic stress and burnout, and evidence-based coping and wellness skills.

Tier III interventions: long-term recovery phase

For many survivors, Tier II intervention will be all they need to psychologically recover after a disaster. However, in cases in which more intensive mental health treatment is required, providers can identify this need and refer to specialized psychotherapy services24. Tier III interventions are trauma and grief interventions for children and adolescents who require formal, evidence-based mental health treatment24.

The two treatments with the most empirical support are Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS)25, which is appropriate for addressing moderate trauma-related symptoms in a group-based format, and Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TFCBT)26, which is most appropriate for addressing moderate-to-high trauma-related symptoms in an individual format. Triage to one or the other would depend on the severity of symptoms and whether group-based treatment or individual treatment is most appropriate.

Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS)25 is a school-based group intervention aimed at relieving moderate symptoms of PTSD, depression, and general anxiety among children exposed to trauma. Children are provided with normalizing education about common reactions to stress and trauma and learn skills such as relaxation, how to challenge and replace upsetting thoughts, and problem-solving. Children also work on processing traumatic memories and grief in both individual and group settings. The program consists of 10 group sessions (6–8 children per group), 1–3 individual student sessions, two caregiver meetings, and an optional school staff information session. All sessions are conducted within schools and designed to be delivered within a class period. CBITS is for students in grades 5th and older. There is a K–5th grade developmentally adapted version of this protocol called Bounce Back, which targets the same components as CBITS but is developmentally appropriate for younger children.

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)26 is an empirically validated, multicomponent psychotherapy model that addresses moderate-to-high trauma-related symptoms, including PTSD, depression, and moderate behavioral problems. TF-CBT is designed for children and adolescents ages 3–18 and can be delivered within schools, clinics, via telehealth, or in the community. The typical course of treatment is 12–16 sessions, with a longer duration (up to 25 sessions) for complex trauma. TF-CBT uses individual parallel sessions with the child and supportive caregiver, as well as conjoint parent-child sessions. The intervention includes eight treatment components that comprise the acronym “PRACTICE” (a) Psychoeducation and parenting skills, (b) Relaxation, (c) Affective expression and modulation, (d) Cognitive coping, (e) Trauma Narrative (TN) development and processing, (f) In vivo mastery of trauma reminders, (g) Conjoint sharing of the TN, and (h) Enhancing future safety and development.

Project MHAT Puerto Rico

Background and context

Hurricane Maria, a Category 5 hurricane, impacted Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017. The first author is a native of Puerto Rico and a faculty member at an academic medical center in the mainland US (Medical University of South Carolina-MUSC), along with the second author. They quickly established a relationship with the Puerto Rico Department of Education (PR-DE) through a mutual colleague who connected with them after the hurricane. Within three weeks post-disaster, the MUSC team landed on the island to bring supplies (e.g., batteries, clothing, medications) and to meet with the PR-DE leadership to better understand their needs and offer assistance. During this initial trip, the MUSC team offered several Psychological First Aid (PFA) workshops across the island. During one of these PFA trainings on the West Coast of the island, a faculty member from Albizu University attended and connected with the MUSC team. They remained in communication to explore potential avenues for future collaboration. In the Spring of 2018, the MUSC team returned to Puerto Rico and met with the Albizu University team to better understand their ongoing needs post-Hurricane Maria and explore potential opportunities for collaboration.

Using a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach

A Community-Based Participatory Research approach16 is a partnership approach that equitably involves community partners, stakeholders, and academic researchers in all aspects of project design and implementation to collectively address complicated, real-world problems. CBPR is based on the following principles: (a) building on community strengths and resources; (b) fostering collaborative, truly equitable partnerships between researchers and community members; (c) bi-directional learning between academic and community partners; (d) balancing the acquisition of knowledge with the provision of useful interventions that can benefit the community; (e) focusing on the immediate relevance of mental, social, and physical health problems to communities; (f) using a collaborative and iterative process to review the project’s progress and adjust accordingly; (g) sharing results with partners in a way that is clear, useful, and respectful; and (h) making a long-term commitment to the community with a focus on sustainability.

Using a CBPR approach, our teams came together (round table discussion) to understand the needs that the psychology faculty at Albizu University were noticing in their communities, schools, and graduate training programs to brainstorm together how to best address them (either by the MUSC team offering some resources/ideas or connecting them to other agencies or individuals best suited to help meet their needs). The following needs and gaps were identified: 1) their graduate programs did not offer specialized training in trauma or disaster-informed interventions; 2) the schools in which their graduate students did their practicums were concerned about the significant mental health needs of students (and teachers) and the limited access to resources and referral options- leading to many teachers and school staff feeling overwhelmed and ill equipped to address the mental health concerns of students post-disaster; 3) schools were reporting significant suicidal crises and difficulty managing these; 4) there was a significant shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists on the West coast of the island, making it nearly impossible to get appointments for students in need of medication management; 5) faculty themselves felt they needed training in best practices for psychological interventions post-disaster and other potentially traumatic events; 6) there appeared to be a breakdown in collaboration and communication between the mental health agencies on the island, making it difficult to refer youth in need of services or to understand the types of services available to youth; 7) the mental health resources and trainings faculty often had access to or found online were mostly in English (not in Spanish) making it difficult to use in the context of Puerto Rico.

Informed by CPBR principles, the first and second authors first focused on validating these concerns and acknowledging the Albizu University team (led by the third author) for their commendable efforts and self-efficacy in assisting their communities despite these barriers. For instance, the Albizu University team used the Psychological First Aid manual in Spanish (available for free through www.nctsn.org) to help communities in need after Hurricane Maria. They had also created brigades of graduate students and faculty that reached some of the most affected communities and distributed food, water, clothing, and other basic needs (more detailed information about this initiative can be found in a previous publication)27.

Second, the MUSC team and Albizu University team agreed to come together in a follow-up meeting to discuss potential ways to collaborate to meet some of these identified needs. Given the limited expertise the MUSC team had regarding psychiatric care on the island, an additional partnership was established with the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences campus, led by the fourth author. During this time, a call for a Mental Health Awareness Training Grant (MHAT) from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) was announced in the Summer of 2018. The specific goals of this grant aligned with the needs of Albizu University, which included training the mental health and allied workforce in mental health awareness training aimed at identifying and referring youth in need of mental health services. Our teams came together and co-created and wrote a grant aimed at 1) providing targeted training to the next-generation mental health and allied professionals, teachers, and community members in evidence-based, disaster and trauma-informed mental health awareness training (MHAT) programming; 2) identifying and referring children in need of mental health services in Puerto Rico; and 3) implementing the first-ever school-based telepsychiatry consultation program in Puerto Rican public schools. The three-year grant was awarded in November of 2018, and implementation efforts began in January of 2019 (See Fig. 2 for a Timeline).

PFA Psychological First Aid, PRDE Puerto Rican Department of Education, MUSC Medical University of South Carolina, SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, MHAT Mental Health Awareness Training Grant, PR Puerto Rico, UPR University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus, Albizu Albizu University, Mayaguez Campus.

Implementation process and outcomes

Project Goal #1: Trauma and Disaster-Informed Mental Health Awareness Training (MHAT)

Our approach was to train graduate students in master’s and doctoral level psychology programs and their faculty supervisors in various mental health awareness trainings (see below Table 1 for a description of each MHAT) and for graduate students and faculty to then offer these to teachers, school staff and caregivers within local public schools to identify and refer students in needs of mental health services post hurricane Maria. At the start of implementation, Albizu University had collaborative agreements with 12 public schools located in the southwest region of Puerto Rico. Graduate students would spend 1–2 days per week at these schools to meet their graduate school practicum hours requirements. Part of their duties included giving workshops to teachers and school staff on mental health topics, providing psychometric evaluations and psychological services to students, assisting with crises, and making external referrals whenever appropriate. Graduate students were supervised by licensed psychologists on faculty at Albizu University, Mayaguez Campus. It was determined that the best approach would be for the MUSC team to travel to Puerto Rico at the beginning of each semester (fall and spring) to offer the MHATs in person to graduate students and faculty so they could then offer the training in schools during the rest of the semester (train the trainer approach).

The MUSC team had an already established partnership with the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN), which had open access materials and training in trauma and disaster-informed programs. In partnership with the NCTSN, these manuals and materials were translated to Spanish (if not already available) with special attention to the use of local Puerto Rican idioms and vocabulary. In the first year of the grant, the first, second, and last authors delivered these training and materials to all graduate students and faculty at Albizu. Handouts were created and given to teachers and school staff to use with their students (in Spanish and adapted for the local Puerto Rican context). In the following years of the grant, additional collaborators from Albizu University (including the third author) and other local experts on the island began delivering the MHATs (to build local capacity and long-term sustainability).

Outcomes

Our MHAT project provided culturally and linguistically tailored mental health awareness training in Psychological First Aid (PFA), Trauma Informed Care, Suicide & Crisis Management, Skills for Psychological Recovery (SPR), and other MHATs to 9236 psychology graduate students, supervisors, teachers, school staff, parents and community mental health and allied professionals over the four years of the grant (see Table 1).

To assess participants’ perceptions of the workshops and improve future MHATs, three open-ended questions were asked at the end of the training via a brief online survey: 1) What did you like most about the workshop?; 2) What would you have liked more information about? and 3) Any additional comments or suggestions? Overall, participants found the training valuable, informative, and useful. Most indicated wanting to continue receiving our MHAT training in the future, and some provided suggestions for improvements. See Table 2 for sample quotes from participants.

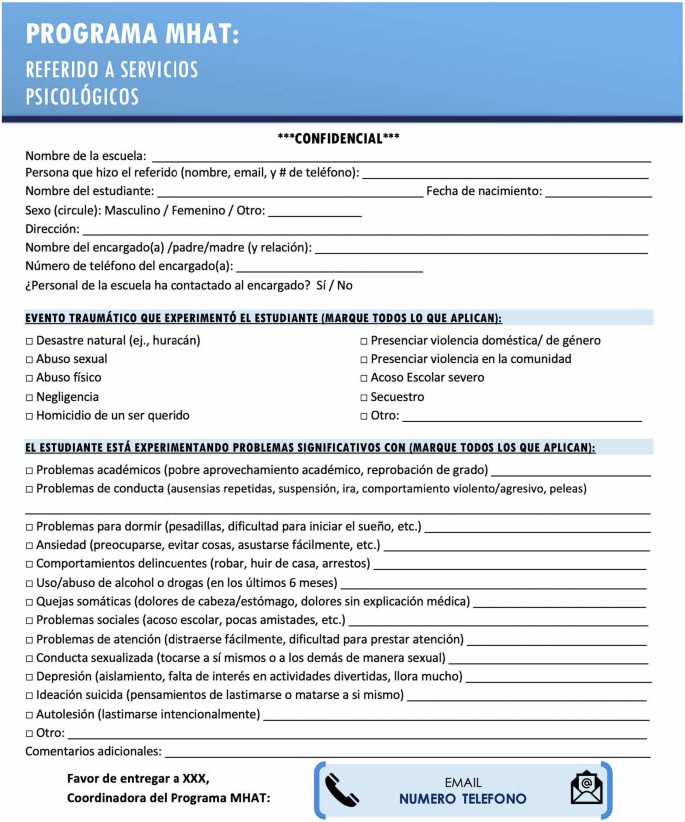

Project Goal #2: Identification and Referral of Youth to Mental Health Services

Graduate students periodically checked in with teachers and school staff to see if any students had been identified or needed mental health referrals and ensured that these students were connected to school-based or community-based services. To aid this process, our team also created a short and practical referral form in Spanish for teachers/school staff to use (see Fig. 3). This referral form included student basic demographic information, a brief trauma events checklist using DSM-5 criterion A examples (e.g., natural disaster, sexual abuse, physical abuse, etc.) that teachers could fill out only if they were aware the student had experienced a traumatic event (if not they could leave blank), and a general problems checklist (e.g., academic problems, conduct problems, sleep problems, anxiety, problems with peers, attention problems, suicidal ideation, etc.). Teachers and school staff could check off any problem areas they noticed in the student and send the referral to our MHAT project coordinator. The third author, a faculty member who coordinated all school practicum sites, would staff the referrals, determine which services would be the most appropriate, and contact the caregiver to provide the available options to connect the student with services, whether these be school-based or community-based. It is important to note that our team was not screening for mental health concerns per se rather, we were supporting teachers and school staff through mental health awareness training on identifying behaviors (“red flags”) for mental health concerns in youth and providing them with a simple process to make a referral. Our team then connected the student to local school or community-based providers who then used their standardized procedures for screening, informed consent, and treatment.

# Number; XXX insert name of program coordinator.

We also established collaborative agreements with the three largest community mental health agencies in Puerto Rico (APS, ASSMCA, and INSPIRA) that offer mental health services to youth and adults and accept all insurance types, including Puerto Rico’s government insurance plan, provide services for free when there is a financial need, and offer in-person and telehealth services. We also were able to refer students to graduate students completing practicums within these schools. These partnerships minimized barriers in access to care related to insurance, distance from the clinic, and/or availability of services.

To further aid with this referral process, our team also created a 1) directory of all community mental health providers trained in Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) in Puerto Rico so that children and adolescents identified as needing trauma-focused services through this MHAT grant could be directly referred and connected with these providers; and a 2) directory of mental health resources in Puerto Rico (providers, different levels of care available, crises lines), updated it periodically, and shared widely with schools, partners, and through our Facebook page.

Outcomes

A total of 652 youth were identified by teachers, school staff, and community members as needing a referral to mental health services or resources. All of these referrals were connected to the most appropriate mental health services either in school-based clinics (operated by school social workers, counselors, psychologists, and/or graduate students doing their clinical practicums within the schools), local community mental health clinics that were also our collaborators on the grant (APS healthcare, ASSMCA, Inspira), our telepsychiatry program in collaboration with University of Puerto Rico, Medical Science Campus or to other local community providers. Referrals were made according to specific mental health needs, level of immediate risk, insurance, and location. Youth were served either in person or virtually (telehealth) due to COVID-19.

Project Goal #3: Telepsychiatry Consultation Program

Most of the island of Puerto Rico is categorized as a mental health professional shortage area15. This component of our project aimed at connecting child and adolescent psychiatry fellows at the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus in San Juan (the capital of Puerto Rico located on the northeast of the island) with teachers, school staff, and practicum graduate students from Albizu University located in 5 pilot schools on the Westcoast of the island. Psychiatry fellows were supervised by the last author, who is a child and adolescent psychiatrist, an expert in telepsychiatry, and directs the psychiatry fellowship program at UPR-CM. Graduate students were supervised by the third author, a licensed psychologist, an expert in telemental health and consultation, and coordinated school-based practicums for graduate students at Albizu University. The first and second authors, national experts in telehealth, provided webinars on best practices for teleconsultation for both the fellows and graduate students and were available for support and consultation as needed.

The goal at the time was to facilitate consultation about mental and behavioral health concerns of students and obtain guidance on how to make behavioral modifications in the classroom, refer to the appropriate level of care for mental health needs (inpatient vs outpatient), connect with local providers for medication management if needed and join Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings for students (referred to in Puerto Rico as “Comité de Ubicación y Planificación”-COMPU) to offer recommendations. The overarching goal was to promote interdisciplinary professional collaboration that was not limited by geographical distance or other logistical barriers. The initial goal of this initiative (pre-pandemic, 2018–2019) was not to provide direct services to students but rather for teachers, school staff, and graduate students to consult in real-time with a psychiatrist on the needs mentioned above. This approach was utilized due to a lack of legislation at the time allowing direct service provision via telehealth.

Our teleconsultation pilot began during the second year of the grant (2019). First, our team met in person with school leadership at the five public schools selected for this pilot program (all located on the west coast of Puerto Rico). We explained the goals of the teleconsultation program and gauged interest, determined the need for internet/ethernet and a private and secure location to have the telepsychiatry consultations via telehealth. We installed laptops with HIPAA-compliant teleconferencing software, met with PR-DE IT support staff to help install internet and ethernet ports in schools that lacked internet access, tested the equipment, trained staff, and graduate students on how to use it, created fact sheets explaining the teleconsultation program, and obtained a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) from the Puerto Rico Department of Education for the use of teleconsultation during IEP meetings.

Outcomes

A total of 7 teleconsultations were completed in the first four months of the program (November 2019–February 2020). School administrators and staff reported liking this program (being able to connect with a psychiatrist to consult on concerns with a student’s mental health and obtain information on referral options) due to the limited availability of child and adolescent psychiatrists on the island. Psychiatry residents also reported enjoying this school-based teleconsultation practicum as it allowed them to be more involved with a multidisciplinary and community-based team. Specific challenges and solutions are discussed in the next section.

Unfortunately, the program had to be paused due to school closures because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our team pivoted and picked up the telehealth equipment from the schools and loaned it to Albizu University graduate students so that they could begin offering therapy to youth via telehealth from April 2020 onward (due to an island-wide lockdown). Having this teleconsultation program in place before the start of the pandemic afforded Albizu University graduate students and faculty the ability to easily begin offering services via telehealth with students and staff already familiar with telehealth equipment and best practices and HIPAA-compliant telehealth software and equipment. Furthermore, the already established relationship with UPR psychiatry residents allowed for youth from the western part of the island to be referred to a psychiatrist in the northeastern part of the island and receive treatment and medication management via telehealth due to legislation authorizing the use of telehealth for psychiatric medication management and other mental health services as a result of the pandemic (Ley 48 del 29 de abril del 2020: Ley para Regular la Ciberterapia en Puerto Rico)28.

Project Goal #4: Social Media Mental Health Awareness Marketing Campaigns

Our team engaged in several social marketing and mental health awareness campaigns to share culturally and linguistically tailored resources and tools with a broader audience. We first created a Facebook Page to market our free training, share free mental health awareness training resources that were culturally and linguistically tailored to Puerto Rico, and promote mental health awareness campaigns relevant to our audience, such as “Self-compassion and self-care during the anniversary of Hurricane Maria” (https://www.facebook.com/toptelesalud).

Throughout the grant, we also offered a series of Facebook Lives to promote mental health awareness topics in Puerto Rico, including one geared towards 1) Parents/Caregivers: How to identify signs and symptoms of mental health concerns in youth during COVID, coping tools, and how to connect with services and 2) Mental Health Professionals: How to identify signs of burnout, coping tools, and how to connect with services. In response to ongoing disasters that PR continued to experience, we created a YouTube channel with short clips (in Spanish) offering tips for how to implement Psychological First Aid (PFA) after a disaster and other topics such as: provider burnout, self-care, how to identify and cope with depression, anxiety, substance use, and other mental health awareness topics that are updated continuously. (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCIA__8GKxb-HQDs_NYvDAQg).

Outcomes

Currently, our Facebook page has 3184 page followers (most of which are mental health professionals and community partners in Puerto Rico) and 2627 page likes. Our YouTube channel has over 1314 views and 172 subscribers. Our MHAT program was recently featured in a podcast interview with the US Surgeon General titled “What do natural disasters mean for our mental health?”- https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/house-calls/index.html. This Podcast has 854 views on YouTube.

Challenges and Solutions

In this section, we offer some challenges our teams faced during the implementation of this project and how we collaboratively came up with creative solutions with our partners to overcome these challenges.

Pivoting away from a “one-size fits all” train-the-trainer approach

Our original plan was to train graduate students in these various MHATs and have them go to their practicum school sites and train teachers, school staff, etc., in these various MHATs (“train-the-trainer approach”). This was a challenge for students, however. They reported that they did not feel confident in offering training on a topic they were still becoming familiar with themselves. Others reported that they found the slide decks somewhat confusing. Others felt anxious offering the training given they were only recently starting their practicums at the schools. As such, we pivoted away from a train-the-trainer approach with graduate students, and instead, our MHAT leadership team (authors of this manuscript) began offering all the MHATs directly to our target audiences and instead finding “champion” collaborators on the island who expressed interest co-training with us or who had expertise in these topics who then joined our core training team with our ongoing support. Graduate students appreciated the opportunity to hone their skills and focus their efforts on helping teachers connect students in need of mental health services with the appropriate referrals.

Shift from in-person to virtual training

During Years 2 and 3 of our grant, schools in Puerto Rico were closed (all learning was virtual) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our team shifted to offer virtual MHAT training using Zoom or Microsoft Teams platforms. This shift did not affect our program. Rather, we were able to train significantly more graduate students, teachers, school staff, caregivers, and mental health providers in the community than we had in the previous years and to reduce costs. We attribute this to the virtual format, which addressed barriers to attending in-person training, such as time off from work, transportation, and lack of physical space.

Focus on COVID-19 mental health awareness and telehealth resources

Our grant was not originally written to bring mental health awareness training on the impact of a global pandemic or the use of telehealth to deliver services. Considering COVID-19, the needs of our communities shifted, and in true CBPR fashion, we flexibly adapted to create additional MHAT training that addressed these important topics to meet the needs (see Table 1 for a description of MHATs). We also began an online support group for teachers who needed mental health support during the pandemic and connected them to mental health referrals as needed.

Expansion of our target audience & topics

Given the additional disasters that impacted Puerto Rico during our grant period (e.g., more hurricanes, flooding, earthquakes, a global pandemic), we received numerous requests to open our virtual MHATs (particularly Psychological First Aid) to first responders, public health officials, faith and community leaders, and students from other universities across the island. Thus, we decided to expand our target audience to meet the needs of our partners and stakeholders as well as form new collaborations (consistent with CBPR principles). Additionally, we: 1) incorporated psychoeducation about the mental health impact of COVID-19 on children and adolescent mental health; 2) offered Facebook Lives to reach a broader audience (especially caregivers/parents and teachers); 3) adapted our referral process so that social workers and teachers who identified children in need of mental health services could be connected to graduate students or community mental health providers offering telehealth services; 4) expanded collaborations with other government agencies and non-profits; 5) offered additional MHAT training on the use of telehealth technology with youth; and 6) noted that for future grant applications, it will be important to highlight the importance of offering training in Psychological First Aid and other mental health awareness training to faith-based leaders as they play a vital role in Puerto Rican communities. It will also be important to ensure that materials are adapted for this target population.

Culturally and linguistically tailored resources

Our MHAT grant was based in Puerto Rico, a US Territory where the primary language spoken is Spanish. There is a surprisingly limited amount of mental health awareness resources available in Spanish. To address this, our team created tip sheets, PowerPoints, handouts, factsheets, short videos, and webinars – in Spanish- that are tailored to the local Puerto Rican post-disaster context. All these resources were distributed freely to our community partners, and all are open-access and available for free online thanks to a partnership with the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, which is also funded by SAMHSA. Some examples of these resources are the following pre-recorded webinars:

-

1.

Psychological First Aid (PFA) webinar in Spanish (filmed for Puerto Rico) available for free as a 3 CE course through the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (also funded by SAMHSA) https://learn.nctsn.org/course/index.php?categoryid=11.

-

2.

Skills for Psychological Recovery (SPR) webinar in Spanish (filmed for Puerto Rico) available for free as a 3.5 CE course through the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (also funded by SAMHSA) https://learn.nctsn.org/course/index.php?categoryid=11.

Pivoting from teleconsultation to telepsychiatry direct service provision

We piloted the telepsychiatry consultation program in Nov-Dec of 2019. Graduate students and teachers liked being able to consult on cases, and psychiatrists appreciated participation in a multidisciplinary, school-based team. Challenges included difficulty with the internet/Wi-Fi (which was unstable at times) and teachers being able to find time in their busy schedules to connect with the psychiatrist. Graduate students also reported being unsure about what they could and could not consult with a psychiatrist- signaling the importance of educating psychologists in training in this important skill of professional communication.

We hoped to expand the program in January 2020, but due to the earthquakes that occurred in the Southwest part of the island (where our grant was located), schools in our catchment area were closed until they passed a building infrastructure inspection. We were hopeful the program would start by March 2020, but then COVID-19 resulted in an island-wide lockdown. Given the mandate for schools to transition to fully virtual instruction and new local legislation allowing telehealth delivery of mental health services across the island during the emergency (Ley 48-2020 Para Regular la Ciberterapia en Puerto Rico28), we pivoted and re-purposed the telehealth equipment by giving it to graduate students to offer therapy appointments via telehealth to students in need of services. Graduate students on the island benefited greatly from having been trained in using this telehealth equipment before the pandemic, and the Albizu University mental health clinic, was able to transition more swiftly to offering telehealth services as a result. Due to the new telehealth legislation, psychiatrists were also now able to offer direct services to youth via telehealth and send electronic prescriptions to pharmacies across the island (including controlled substances). Thus, we converted our teleconsultation program to one of direct service provision. However, two challenges emerged. First, some youth lacked of access to the internet and equipment (e.g., tablets/computers) to properly engage in services via telehealth. In the future, we consider it important that grants that fund direct service provision to youth consider the potential for internet/hotspot and equipment loaner programs (i.e., families could rent hotspots and iPads/tablets to engage in therapy services) to increase access to mental health services for youth. Interestingly, we did not encounter stigma as a barrier to accessing mental health services. Quite the opposite, caregivers and youth were eager to receive mental health services and frustrated about long wait lists to receive services. Second, despite legislation allowing for providers to send electronic scripts to pharmacies, many were not accepting them (e.g., were concerned about this new legislation/were not familiar with it), especially with controlled substances, which are often prescribed to manage psychiatric conditions (e.g., ADD/ ADHD). This resulted in problems with securing medications for some youth (particularly those with ADD/ADHD) given caregivers had to drive (often 2–3 h) to get a physical copy of the prescription from their provider who had seen them via telehealth, thus defeating the purpose of this service delivery modality. This barrier is of particular importance moving forward as the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is in the process of revising guidelines on the prescription of controlled substances and is considering returning to more restrictive prescribing measures of controlled substances when using telehealth.

Managing compassion fatigue and burnout

Our team is comprised of faculty members and graduate students who either live in Puerto Rico, identify as Puerto Rican, or have very close ties to the island. Being in the role of the helper while going through similar losses, adversities, and traumatic events as the population you are trying to serve can take a toll, particularly for our team members on the island. During this grant, Puerto Rico experienced multiple disasters, including hurricanes, earthquakes, a global pandemic, and an ongoing energy crisis. We quickly realized we had to “put on our oxygen mask first, before assisting others.” And that those who were training and were in helping roles (e.g., teachers) also needed assistance and support. We addressed this challenge in three ways: 1) we created a team WhatsApp group to make sure we kept open lines of communication and offered each other support; 2) we normalized “tapping out” whenever any of us felt burnt out or impacted ourselves (e.g., The third author recalls a specific hurricane in which her family was impacted and she did not feel she was in a position to offer Psychological First Aid training. Instead, she helped by forwarding resources and links to those who texted her for help, and the rest of our team focused on providing the training); and 3) we created virtual self-care groups for teachers (offered in the evenings to facilitate access) in which we introduced the concepts of compassion fatigue, burnout, self-care, and mindfulness, to facilitate support and community building for these professionals. We learned from these experiences the importance of checking in on our team members, creating a sense of community, applying the same principles we were teaching others to ourselves, and offering not just didactic training but spaces where people could come together to share and feel supported. More information on this topic can be found in a previous publication27.

Discussion

Nearly 1 billion children worldwide are at an ‘extremely high risk’ of the physical, psychological, and social impacts of climate change3. Over the past five years, the island of Puerto Rico has been significantly impacted by disasters, including multiple hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, and a global pandemic. Yet most individuals who interact with youth regularly (e.g., teachers, school staff, caregivers), and even some mental health providers, receive limited-to-no training in how to assist youth impacted by disasters and resulting adversities. To meet this need and guided by CBPR principles, three universities (one in South Carolina and two in Puerto Rico) partnered and applied for a SAMHSA Mental Health Awareness Training grant. Over four years (2018–2022), our teams offered evidence-based, culturally and linguistically tailored mental health awareness training in the topics of trauma and disaster response, including Psychological First Aid (PFA), Trauma Informed Care (TIC), Suicide & Crisis Management, Skills for Psychological Recovery (SPR), and Secondary Traumatic Stress and Self Care to 9236 psychology graduate students, supervisors, teachers, school staff, parents and community mental health and allied professionals across the island of Puerto Rico utilizing in-person and virtual training modalities and supports. Our project led to the identification and connection to mental health services of 652 Puerto Rican youth. Our trauma and disaster-informed mental health awareness training program was featured by the US Surgeon General as a potential model to help meet the mental health needs of disaster-affected youth due to climate change.

We believe our program was successful for several reasons (which we recommend those interested in doing this type of work take into consideration). First, we were guided from the beginning of the project by CBPR principles. That is, our sole focus was to understand the needs of our community partners and to co-create the project goals and implementation strategies. To this effect, our grant application emerged from a collaborative needs assessment, was co-written with our community partners, and was designed to meet their unique needs. Second, we implemented our training within an already existing infrastructure (graduate school training program that had school-based practicums) to maximize the probability that training would be well attended, received, and utilized. In other words, our MHATs were not imposed or another “to-do” for our target audience. Rather, these trainings were required as part of graduate coursework and embedded within the different services Albizu University offered to schools and staff (e.g., beginning of semester mental health workshops for school staff and parents). As such, participants did not feel it was a burden to attend these trainings. Third, our training and resources emerged out of the specific needs that teachers, school staff, and graduate students and faculty were noticing in the youth they served. Thus, the information received was highly valued and viewed as useful to help youth get connected to necessary support post-disaster and exposure to traumatic events.

We also expanded our target audience based on requests from these different audience members themselves (community organizers, faith leaders, physical health providers, first responders, and community mental health professionals) who contacted us wanting to join our training because they saw a need to become trauma and disaster-informed in their work with youth. Fourth, we did not “reinvent the wheel.” All our MHATs had been previously developed by organizations such as the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN). What our team did do was translate and culturally tailor resources whenever necessary, offer the training in Spanish by Puerto Rican trainers, and make resources accessible to our local audience via social media and open-access platforms. Fifth, we developed close relationships with various mental health agencies on the island by offering MHATs to the agency’s staff. This, in turn, allowed us to create more streamlined referral processes for students in need of services given our ongoing relationship with these agencies and their knowing our team and our commitment to child mental health. Finally, we continually followed the need. That is, whenever our partners or various audiences expressed wanting more information about a certain topic, we created new MHATs that were responsive to their needs. Having supportive Grant Program Officers at SAMHSA also allowed us to be flexible in our implementation approaches and engage in truly partnered work that centered our collaborator’s needs above our own.

Sustainability should always be at the forefront when implementing a program. To this effect, we: 1) ensured that some of our grant consultants, team members, and graduate students based in Puerto Rico are now able to replicate these MHAT training in their organizations, schools, and communities; 2) created open access resources that are disseminated in our social media platforms (Facebook, YOUTUBE channel); 3) partnered with the National Child Traumatic Stress Network to upload some of our MHAT training (PFA and SPR) in Spanish to their online learning center web-page so that more can have access to these training, regardless of MHAT funding; 4) continued to join community advisory meetings and collaborative groups we were invited to participate in and 5) applied to and received additional funding from SAMHSA to continue our MHAT grant (2023-2026). We recommend other teams interested in this type of work think about sustainability from the outset of their design, particularly how they can instill and promote local capacity when doing trauma and disaster-informed work in their communities.

Future directions

Now that our team has helped train a large part of the Puerto Rican youth workforce in how to identify signs and symptoms of mental health concerns in youth and how to connect them with appropriate services, it is important to explore how to increase access to mental health services for youth on the island. Currently, many clinics have long waitlists, a shortage of providers (in great part due to increased migration of professionals to the states in search of living wages), and families cannot access services due to difficulties taking time off from work, lack of transportation, or a shortage of specialists in their geographic area. One potential solution to this problem is creating school-based telehealth clinics where specialists can connect with students to offer services. Our team is currently implementing the first school-based telepsychiatry clinic in the island municipality of Culebra (a small island located off the southeast coast of mainland Puerto Rico). Culebra is only accessible via boat or small plane, and access to specialized mental health services such as psychiatrists is not available locally. In partnership with the local public school in Culebra, our team helped create a telepsychiatry clinic in which students can be seen by child and adolescent psychiatrists located at the University of Puerto Rico and receive evaluations, medication management, and psychotherapy as needed. We are hoping to continue adding similar school-based telehealth clinics across the island in collaboration with the Puerto Rico Department of Education. Another potential solution is to engage community-based youth-serving organizations, sports or coaching staff, and/or faith-based leaders in Tier 1 (Psychological First Aid) and Tier 2 (Skills for Psychological Recovery) training and delivery to increase access for youth who may not have access immediate access to a licensed mental health provider. Ultimately, we must keep thinking “outside the box” and ask ourselves, “Who else can we bring into the fold?” for long-term sustainability and equitable access to mental health care for Puerto Rican youth.

Our team was recently awarded three more years of SAMHSA MHAT funding to continue the implementation of our project. We have expanded our target audience to include any health or mental health professional, faith or community leader, first responder, or paraprofessional working with youth who has an interest in becoming trauma and disaster-informed. We have expanded our topics to include the unique mental health needs of Puerto Rican LGBTQ+ youth. Finally, we have partnered with the Continuing Education division of Albizu University to be able to offer continuing education credits to mental health professionals when they take one of our MHAT trainings. We also plan to be more intentional about sharing the results of this project with community members (youth, teachers, families, providers, and participants) and eliciting feedback and their ideas for how we can improve this project. Ultimately, our goal is to become an open-access hub for training and resources that are evidence-based, trauma and disaster-informed, and that are culturally and linguistically responsive to the unique needs of the Puerto Rican people living on the island.

Climate change will continue to increase the risk of children experiencing adverse events and associated mental health problems. The significant mental health professional shortages that exist across the globe, particularly in Puerto Rico, necessitate creative and innovative solutions to increasing access to evidence-based mental health care for youth. Training the mental health and allied workforce (e.g., teachers, school staff, parents, lay providers, and community members) in evidence-based models of care for disaster and trauma-affected youth is a potential solution, as is the use of school-based telehealth clinics and mental health awareness campaigns via social media.

We believe that our journey using CBPR principles, co-creating and implementing a federally funded mental health awareness training program in partnership with two universities in Puerto Rico, and lessons learned shared in this manuscript can contribute to meeting the needs of children’s mental health, not just in Puerto Rico, but across the world. For instance, we encourage readers to consider how they can use our project as a “roadmap” to launch similar initiatives in their communities. For instance: 1) using CBPR principles to engage in open and intentional dialogue with community members about youth mental health needs and being intentional about incorporating youth voices; 2) incorporating a multi-tiered response to intervention that capitalizes on community members that may not necessarily hold a mental health degree (e.g., faith-based leaders, coaches, non-profits leaders, peer advocates), but have so much to offer our youth to support their mental health, with the proper training and support, and can serve as a way to address the limited access to professional mental health providers across the globe; 3) incorporating the use of open-access, easy to use resources to disseminate mental health awareness information such as short videos, visually appealing fact-sheets, and social media campaigns that are accessible in multiple languages and attuned to the local context and culture; and 4) fostering community and academic partnerships that are equitable and aligned with the values of serving communities rather than extracting from communities. The future of children’s mental health across the globe is dependent on innovative solutions that can only emerge out of equitable partnerships, intentional collaborations, and the courage to challenge the status quo. For an auditory elaboration of some of the material discussed in this paper, we encourage the reader to listen to our podcast interview with the US Surgeon General titled “What do natural disasters mean for our mental health?”- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ki2PmqTnIY8.

Responses