Explaining key stakeholders’ preferences for potential policies governing psychiatric electroceutical intervention use

Introduction

Psychiatric electroceutical interventions (PEIs) treat psychiatric disorders using electrical or magnetic stimulation to alter brain activity. PEIs include both Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved modalities, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), and also interventions that remain largely experimental for psychiatric conditions, such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) and adaptive brain implants (ABIs). These interventions are notable for their potential to treat major depressive disorder (MDD).

Although the recommended front-line treatments for MDD are psychotherapy and antidepressant medications, only 70% of patients achieve remission after treatment with four antidepressants1. Evidence demonstrates that ECT and rTMS are effective for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD)2,3. However, widespread adoption of these therapies is constrained by practical barriers affecting their availability4,5, negative public perceptions of ECT6,7, and state regulations restricting the use of ECT (e.g., specifying rules about patients’ informed consent and age, providers’ professional qualifications and required reporting, etc.)8.

Over the last five years, legislators in a number of states have proposed laws governing the use of PEIs. Most proposed policies aim to reduce rather than expand the use of ECT. They range from age-based restrictions9,10,11,12,13 to outright bans14. At the same time, proposed legislation in at least one state supports greater access to ECT15, and bills in a few other states aim to increase the availability of rTMS16,17,18.

While many studies analyze how relevant stakeholder groups (e.g., psychiatrists, patients, caregivers, and the general public more broadly) view PEIs, we are unaware of any that examine how such views relate to support for or opposition to existing laws or proposed policies governing their use. This gap in the literature is consequential for three reasons. At the most basic level, better understanding how various interested parties’ knowledge and values influence their policy preferences is a fundamental aspect of effective, responsible, and evidence-based policymaking19. Second, different stakeholders bring expertise, insights, and valuable knowledge from their respective domains that could help improve the design and implementation of public health policies. Third, characterizing stakeholders’ policy preferences can help scholars and policy analysts more accurately estimate the likely effectiveness (and identify potential unintended consequences) of such health policies. Policies with broad-based support from a range of stakeholders are more likely to be implemented effectively and produce their intended outcomes than are those facing substantial opposition or confusion from at least one relevant stakeholder group.

Our study aims to fill this gap while also contributing to the wider literature on different stakeholders’ views of PEIs. Recent research finds that important views about PEIs vary by stakeholder group (i.e., psychiatrists, patients, caregivers, and the general public), PEI modality (i.e., ECT, rTMS, DBS, and ABIs), and depression severity (i.e., moderate or severe).7 Further, there is some evidence that PEI modality moderates the influence of stakeholder group membership on key PEI views. We extend this recent work by examining how such factors—as well as key PEI views themselves—influence preferences on proposed state policies that either expand or reduce availability and use of PEIs for treating depression.

Methods

Study design

We administered a standardized survey with an embedded video vignette experiment to four large US samples of the general public, caregivers, depressed patients, and board-certified psychiatrists, respectively. After securing a human subjects exemption from Michigan State University’s Institutional Review Board (STUDY00001247), we contracted with Qualtrics (an online survey platform and online panel provider) to host the survey, which was completed by participants between April and June 2020.

We employed a between-subjects 4 × 2 full factorial design for our embedded experiment. Crossing the two factors—intervention type (DBS vs. rTMS vs. ECT vs. ABIs) and disease severity (moderate vs. severe depression)—produced eight total conditions into which participants were randomly assigned. All participants received the same set of core questions, in addition to a few different questions unique to each stakeholder group.

Participants

To draw our three non-clinician samples, we contracted with Qualtrics, which manages a large internet panel (i.e., sampling frame) designed to capture the demographic diversity of the US adult population. For our general public stakeholder group, Qualtrics drew a quota sample of 1022 adults from this sampling frame that matched adult population estimates of age, sex, race, and income from the US Current Population Survey. For our caregiver stakeholder group, Qualtrics applied a screening question in addition to the population estimate matching to select 1026 adults who were currently serving as the primary caregiver for someone with depression. For our patient stakeholder group, Qualtrics drew a quota sample of 1050 adults with depression from a separate internet panel of adults who had previously reported having a depression diagnosis. Our patient sample matched age, sex, and race estimates of the US adult population living with depression in 202020.

Our research team managed the recruitment and sampling of our psychiatrist stakeholder group. Our sampling frame contained the 49,431 board-certified psychiatrists listed in the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology directory in late 2019. We used stratified random sampling—stratifying by state—to contact 16,190 US psychiatrists across all 50 states. Employing the Tailored Design Method21, widely considered as best practice in survey research, we contacted this group multiple times via postal mail and email—achieving a sample of 505 US psychiatrists who fully completed our survey. Supplementary Table 1 displays key social and demographic characteristics for each of our four samples in this study.

Procedures

After providing informed consent, participants answered a few initial questions and viewed a randomly assigned video vignette22,23. We carefully crafted and filmed the video vignette—featuring professional actors playing a patient named “Mary” with (moderate or severe) treatment-resistant depression (TRD) symptoms receiving information about a PEI from her psychiatrist named “Dr. Wilson”24,25. Supplementary Table 2 contains links to each of the eight video vignettes. After completing a few questions assessing their understanding of the experimental message26, participants then answered several questions measuring their views about the intervention featured in their video as well as their demographic, social, and political characteristics.

Variables

The research team created several novel instruments to measure key PEI views through a multi-stage process involving insights from and revisions after: (a) a review of the relevant literature; (b) 48 semi-structured interviews with psychiatrists, patients, and members of the general public27,28; (c) four rounds of pilot testing; (d) feedback from our Scientific Advisory Board comprised of scholars with expertise in psychiatry, neuroethics, and ethics; and (e) a round of (talk-aloud) cognitive testing with two patients and a psychiatrist. This process—with the results of a principal components analysis and a reliability analysis—informed our creation of eight composite scales. Within each of these instruments, we randomized the item order to eliminate question order effects.21 Supplementary Table 3 displays the survey question wording and response category coding for each of the scales we used in this study.

Outcome variables

Our two outcome variables are composite scales that measure participants’ preferences on six proposed state-level policies that either would expand or restrict PEI access and use for treating clinical depression. For ease of interpretation, we coded both scales so that lower values represent more negative sentiment toward PEI access and use and higher values represent more positive sentiment toward PEI access and use. The 3-item Support for Expanded PEI Use Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.74), ranging from “strongly oppose” = 1 to “strongly support” = 7, measures participants’ views toward using state tax revenue to fund more research on their assigned PEI, to help pay the costs of the assigned PEI for indigent patients, and for requiring access to the assigned PEI in at least one medical facility in each county in the state. The 3-item Opposition to Reduced PEI Use Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.65), ranging from “strongly support” = 1 to “strongly oppose” = 7, measures participants’ views toward prohibiting the use of the assigned PEI until there is more evidence of its safety and efficacy, prohibiting the use of the assigned PEI with minors, and banning the use of the assigned PEI outright.

Stakeholder group and experimental variables

We modeled the main effects of stakeholder group membership (i.e., psychiatrists, patients, caregivers, and members of the public) and the experimental factors (i.e., PEI modality and depression severity) with dummy variables. For the former, we used three dummy variables of public, caregivers, and patients, with psychiatrists as the reference category. For PEI modality, we used three dummy variables of rTMS, DBS, and ABI, with ECT as the reference category. Severe TRD distinguishes those participants in the severe depression category from those in the moderate depression category.

Covariates

We employed five composite scales to measure important beliefs and attitudes that participants have about their assigned PEI. These include:

-

a 8-item General Affect Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.93), ranging from “negative” (1) to “positive” (7);

-

a 7-item Perceived Influence on Self Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.94), ranging from “strong negative influence” (1) to “strong positive influence” (7);

-

a 6-item Perceived Benefits Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), ranging from “no benefit at all” (1) to “great benefit” (6);

-

a 5-item Perceived Riskiness Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), ranging from “no risk at all” (1) to “great risk” (5); and

-

a 6-item Perceived Invasiveness Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.90), ranging from “not interfere at all” (1) to “greatly interfere” (6).

We also measured participants’ perception of how bad it would be to live with TRD every day with a single-item (bad daily life with TRD) ranging from “moderately bad” (1) to “extremely bad” (10).

As noted earlier, we asked each stakeholder group a few additional questions beyond those posed to every participant. Non-clinicians reported their prior awareness of a range of psychiatric interventions. The dichotomous prior PEI awareness indicates whether or not (“no” = 0; “yes” = 1) non-clinicians were aware of their assigned PEI prior to the survey. Non-clinicians also reported their level of distrust or trust in mental health information provided by a range of sources. A 5-item Trust in Medico-Scientific Establishment Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.81), ranging from “strongly distrust” = 1 to “strongly trust” = 7, measures the extent to which participants trust their primary care physician, psychiatrists, the scientific community, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Psychiatrists reported their experience referring or administering to patients either ECT, rTMS, DBS, or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). The dichotomous PEI referral or administration indicates whether or not (“no” = 0, “yes” = 1) a psychiatrist had referred or administered to patients either for treatment or in clinical trials any of the following PEIs: ECT, rTMS, DBS, or VNS.

Demographic, social, and political characteristics

Finally, we measured six demographic, social, and political characteristics that we employed as controls in our statistical analyses. We measured sex (“male” = 0; “female” = 1) and race (“non-white” = 0; “white” = 1) with dummy variables. Age varied from “18–24” (1) to “65 or over” (6), and educational attainment varied from “high school diploma or GED” (1) to “graduate degree” (4). We measured political ideology along a unidimensional scale from “very conservative” (1) to “very liberal” (7), and we measured religiosity as the frequency of religious service attendance, ranging from “never” (1) to “at least once every week” (6).

Analytical techniques

We managed the survey data and conducted three stages of analyses using IBM SPSS 24.0-28.0. First, we performed a series of one-way ANOVA tests to examine the differences in means on our six policy preference items across stakeholder groups and assigned PEI modality. Second, we ran a series of multiple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models on data from our pooled sample to examine variation in our two PEI policy preferences scales by stakeholder group, PEI modality, and depression severity, while accounting for participants’ PEI views and their demographic, social, and political characteristics. We included in these multiple OLS regression models interaction terms to examine whether the influence of stakeholder group membership on PEI policy preferences is statistically moderated by PEI modality or depression severity. To reduce the likelihood of multicollinearity problems associated with using higher-order (e.g., interaction) terms in regression models, we created our interaction terms using centered scores (mean – value)29. Supplementary Table 4 contains a set of nested models for each PEI policy preference scale. The page after Supplementary Table 4 offers a brief summary of the results of these models. Also, given the increasing scholarly interest in investigating how views of and experiences with PEIs vary across racial groups, Supplementary Table 7 presents the results of one-way ANOVAs examining how values on each of the five PEI views scales and two PEI policy preferences scales vary by race.

Third, given the patterns found in the first two stages of analyses, we ran separate sets of multiple OLS regression models containing the experimental, covariate, and control variables for non-clinicians and psychiatrists, respectively—allowing us to examine the effects of group-specific variables. Supplementary Tables 5 and 6 contain a set of nested models for each outcome variable for non-clinicians and psychiatrists, respectively. In each, the base model contains four experimental condition dummy variables; participants’ perception of daily life with TRD; and five demographic, social, and political characteristics as controls. The base model in Supplementary Table 5 also includes two stakeholder dummy variables and educational attainment. The PEI views model in each table adds five PEI views scales to the base model. The full model in Supplementary Table 5 adds the Trust in Medico-Scientific Establishment Scale and participants’ prior awareness of their assigned PEI to the PEI views model. The full model in Supplementary Table 6 adds the psychiatrists’ prior experience referring or administering any PEI.

Results

Descriptive results

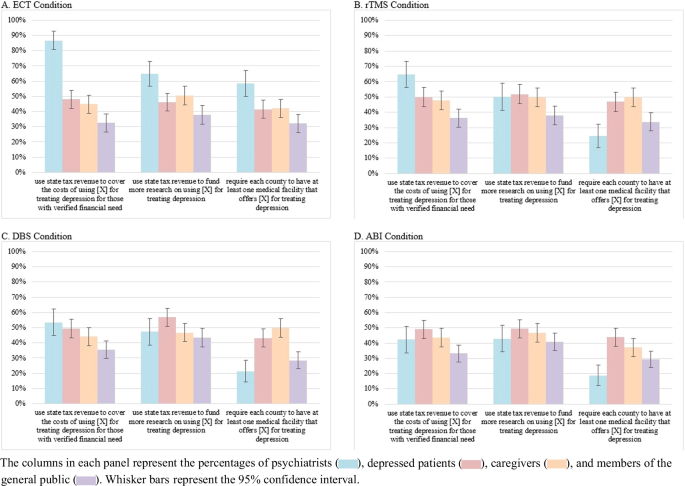

Approximately 45.5% of all respondents supported (but 36.1% opposed) a proposed policy authorizing state tax revenue be used to cover the costs of administering their assigned PEI to indigent patients with depression. Around 47.2% of respondents supported (but 32.4% opposed) a proposed policy directing state tax revenue to fund more research on using their assigned PEI for treating depression. Roughly 38.6% supported (but 44.6% opposed) a proposed policy requiring each county to have at least one medical facility that offers their assigned PEI for treating depression.

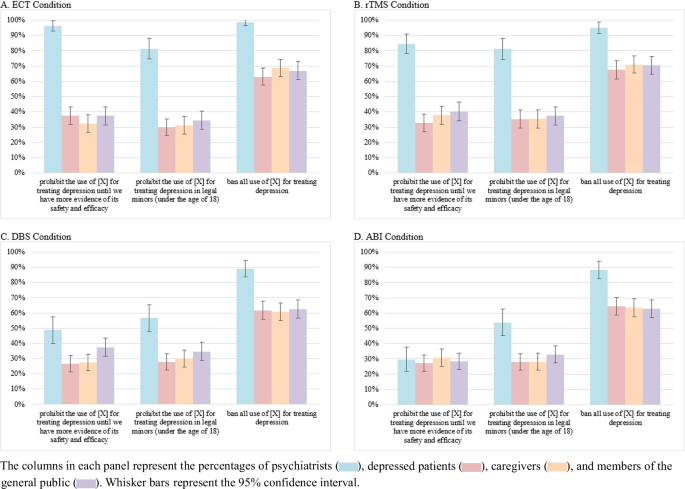

Further, approximately 37.4% of all respondents opposed (but 45.5% supported) a proposed policy prohibiting the use of their assigned PEI for treating depression until we have more evidence of its safety and efficacy. Around 37.1% of respondents opposed (but 49.5% supported) a proposed policy prohibiting the use of their assigned PEI for treating depressing in legal minors. Finally, roughly 69.1% opposed (but 23.6% supported) a proposed policy banning all use of their assigned PEI for treating depression.

Yet, these aggregate percentages conceal substantial variation by stakeholder group and PEI modality. Figures 1 and 2 below display, by PEI modality, the percentages of each stakeholder group that supported three potential policies to expand PEI use and that opposed three potential policies to restrict PEI use, respectively.

A Percentages of respondents assigned to ECT modality. B Percentage of respondents assigned to rTMS modality. C Percentage of respondents assigned to DBS modality. D Percentage of respondents assigned to ABI modality.

A Percentages of respondents assigned to ECT modality. B Percentage of respondents assigned to rTMS modality. C Percentage of respondents assigned to DBS modality. D Percentage of respondents assigned to ABI modality.

Four robust patterns in these two figures are noteworthy. First, across each PEI modality, the three non-clinician stakeholder groups reported similar PEI policy preferences. Further, the similarity in preferences was greater for their levels of opposition to access-reducing policies than for their levels of support for access-expanding policies. Second, when considering PEI modality, we see the greatest divide between the policy preferences of psychiatrists and non-clinicians with ECT than with the other modalities. Third, the divide between the policy preferences of psychiatrists and non-clinicians was greater with opposition to access-reducing policies than with support for access-expanding policies. Fourth, there are only three instances where psychiatrists’ policy preferences were less favorable toward PEIs than were those of any non-clinician group. Compared to patients and caregivers, psychiatrists reported lesser support for a policy requiring each county to have at least one medical facility that offers rTMS, DBS, or ABIs.

Results of OLS regression models

Table 1 below displays the full models for both policy preferences scales for non-clinicians and psychiatrists. We first discuss the results for non-clinicians before discussing the results for psychiatrists. The variables in the non-clinicians’ full models explain between 20% and 33% of the variation in these policy preferences scales, and the variables in the psychiatrists’ full models explain between 38% and 46% of the variation in these same scales.

Compared to the general public, caregivers and patients reported greater support for expanded use—and patients reported less opposition to reduced use—of their assigned PEI. Non-clinicians’ PEI-related policy preferences do not vary across PEI modality or TRD severity experimental conditions. Their perceived badness of daily life with TRD is positively associated with support for expanded PEI use but is unrelated to opposition to reduced PEI use.

Non-clinicians views of their assigned PEIs accounted for nearly all of the explained variance in the Support for Expanded PEI Use Scale (81%) and the Opposition to Reduced PEI Use Scale (95%). Generally, more favorable views of their assigned PEI resulted in more favorable PEI-related policy preferences. While greater trust in the medico-scientific establishment is associated with stronger support for expanded PEI use, it nevertheless has a weak negative influence on opposition to reduced PEI use. Finally, non-clinicians’ prior awareness of their assigned PEI has a weak positive influence on support for the expanded use of the same PEI, but has no influence on opposition to reduced use.

While non-clinicians’ PEI-related policy preferences do not vary by PEI modality, psychiatrists’ policy preferences do. Compared to their peers in ECT condition, psychiatrists in the rTMS, DBS, and ABI conditions reported lesser support for expanding PEI use and also lesser opposition to reducing PEI use. As with non-clinicians, psychiatrists’ PEI-related policy preferences do not vary across TRD severity experimental conditions. Also like with non-clinicians, psychiatrists’ perceived badness of daily life with TRD is positively associated with support for expanded PEI use but is unrelated to opposition to reduced PEI use.

Compared to the patterns seen among non-clinicians, the influence of PEI views on psychiatrists’ PEI-related policy preferences were weaker and less consistent—though in the same substantive direction. Psychiatrists’ views of their assigned PEIs accounted for only a small percentage of the explained variance in the Support for Expanded PEI Use Scale (29%) and the Opposition to Reduced PEI Use Scale (22%). Generally, more favorable views of their assigned PEI resulted in more favorable PEI-related policy preferences. Finally, while psychiatrists’ prior experience referring or administering any PEIs had no influence on their support for expanded PEI use, it nevertheless did have a small positive influence on their opposition to reduced PEI use.

Discussion

Approximately 8.3% of adults and 20.1% of adolescents (12-17 years old) in the USA experienced a major depressive episode in the past year, and approximately 61.0% and 40.6% of these groups, respectively, received some kind of treatment for their MDD.20 Over the last two decades, public stigma toward MDD has declined30. In recent years, especially with the rise of telepsychiatry and mental health apps for smartphones, front-line treatments are increasingly available. Yet, as noted earlier, at least one-third of those diagnosed with MDD see no substantial improvement in their symptoms through therapy and multiple rounds of antidepressants alone.1 For those with TRD, FDA-approved PEIs have proven effective, and experimental PEIs in development hold considerable promise.

State-level mental health legislation facilitates or constrains the availability and use of such PEIs—as shown already with ECT.8 Indeed, elected officials in a number of states have introduced policies regulating the use of certain PEIs in recent years. Our study extends recent work on PEI views by examining the extent to which relevant stakeholder groups oppose or support PEI-related policies and the influence that their PEI views have on these policy preferences.

Our results above and those from similar studies provide insights that may aid the integration of a responsible research and innovation approach31,32 (which can support the ethical development and use of PEIs) and an analytic-deliberative process33,34 (which can guide effective PEI governance by ensuring that public discussion and decision-making on these emerging technologies are informed by the best available science). Neither framework favors any particular substantive outcome; rather, they both emphasize processes that are iterative, transparent, reflexive, and responsive. Above all, both frameworks expect that optimal outcomes are dependent upon the full inclusion of a broad range of relevant stakeholders and affected groups into decision-making processes and the authentic consideration of their values, perceived risks and benefits, and ethical concerns.

To that end, we offer several insights below that may inform subsequent deliberations among relevant stakeholders, even though these insights likely are constrained by three characteristics of our study. First, our national samples likely are insufficient for characterizing the particular PEI views and policy preferences of stakeholder groups in any particular state—the political jurisdiction in which elected officials have introduced nearly all PEI governance policies. This is especially case for our smaller sample of board-certified psychiatrists, which resulted from a low response rate. Second, given the three proposed state-level policies for expanding PEI access and use either directly or indirectly require the expenditure of tax revenues, we cannot rule out that participants’ tax preferences may have influenced their responses. Third, our experiment likely complicates the interpretation of our results, since participants responded only to their one assigned PEI. Subsequent state-level studies in which participants report their views on multiple PEIs may be necessary to gain optimal information in this regard.

With these caveats in mind, we recommend that those involved in creating or revising policies governing the use of PEIs consider the following insights to guide inclusion of relevant stakeholders. Above all, it is important to consider how clinicians and non-clinicians alike perceive these interventions, attending to the direction and magnitude of the association between key PEI views and preferences toward policies that maintain or increase PEI access.

The differences between clinicians’ and non-clinicians’ PEI policy preferences—and their PEI views7—are nontrivial. Further, both divides vary substantially by modality. That is, the differences between clinicians’ and non-clinicians’ views and policy preferences on ECT are greater than they are on rTMS, DBS, and ABIs. Briefly, psychiatrists favor ECT, while non-clinicians fear it. This suggests sizable opportunity gaps for (a) informing non-clinicians about the science of the efficacy and safety of ECT, (b) educating psychiatrists about the types of perceived risks and ethical concerns that non-clinicians have about ECT, and (c) creating opportunities for psychiatrists to learn more about the lived experiences of those who have had PEI treatment.

Among psychiatrists, PEI modality is associated strongly with policy preferences. As noted above, they report preferences more favorable toward maintaining or increasing PEI access when considering ECT than any other PEI. This pattern likely reflects their awareness of the ample evidence of ECT’s effectiveness treating TRD and the lesser amount of such evidence for the other modalities. To a lesser extent, psychiatrists’ PEI views are related to their policy preferences; briefly, more favorable PEI views—independent of modality—are associated with slightly stronger preferences for policies maintaining or increasing PEI access.

At first glance, non-clinicians’ PEI-related policy preferences seem unrelated to their assigned PEI modality. However, these policy preferences do vary substantially by their views about their assigned PEI modality, which are related to modality35. That PEI views at least partially mediate the influence of modality on policy preferences highlights the need to fully acknowledge and discuss these views in deliberations. More strongly than seen with psychiatrists, non-clinicians’ more favorable PEI views—independent of modality—are associated with much stronger preferences for policies maintaining or increasing PEI access. It seems reasonable that these views—such as affect toward their PEI, perceived benefits of their PEI, and perceived influence of their PEI on their sense of self—serve as heuristics to help them make decisions on PEIs in the absence of technical understanding of how they work or scientific knowledge of their therapeutic efficacy.

Further, non-clinicians’ trust in major medical and scientific occupations and organizations has mixed effects on their PEI-related policy preferences: a positive association with support for expanding PEI use but a negative association with opposition to restricting PEI use. Given this, mental health advocates for greater PEI access should not assume that simply building non-clinicians’ institutional trust would necessarily strengthen their support for policies maintaining or increasing PEI access.

Finally, there is some evidence that familiarity with MDD and PEIs shapes stakeholders’ PEI-related policy preferences. For instance, psychiatrists’ and non-clinicians’ perceived badness of living with TRD is inversely associated with their support for expanded PEI use. Further, non-clinicians’ prior awareness of their assigned PEI and psychiatrists’ prior experience referring or administering any PEI are associated with support for expanding PEI use and opposition to reducing PEI use, respectively. Processes that solicit the TRD perceptions of stakeholders with varied familiarity or experience with PEIs likely will yield rich deliberation on the details, costs, and benefits of PEI-related policies. Such an inclusive participatory approach, while challenging to implement36, should help guide more effective PEI governance into the future.

Responses