Myeloid ACAT1/SOAT1: a novel regulator of dyslipidemia and retinal neovascularization

Introduction

Ischemic retinopathies, including diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, and retinal vein occlusion, are common causes of vision loss and blindness in developed countries worldwide1,2,3. Conventional therapies include repeated intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), steroids, vitrectomy, or photocoagulation. All are associated with some risk of damaging side effects, including inflammation, retinal detachment, endophthalmitis, and vitreous hemorrhage. Rapid vascular regrowth may occur upon interruption of the VEGF blockade and its effectiveness is limited in some patients4,5,6,7. Steroid injections can induce increases in intraocular pressure or cataract formation and vitrectomy or photocoagulation can damage healthy cells. These limitations underscore the need for additional effective treatments that reverse RNV and promote physiological repair while avoiding the side effects of current therapeutic options.

In ischemic retinopathies hypoxia, oxidative stress, and inflammation are key factors underlying the retinal damage8,9. Activation of microglia and macrophages also plays a key role in ischemic retinopathy and both cell types are critically involved in the pathogenesis of pathological RNV10,11,12,13,14. Although these factors are all connected, the order of these events and their underlying mechanisms have not been well demonstrated. In this perspective review we will focus on the role of the cholesterol metabolizing enzyme ACAT1/SOAT1 and CE formation in retinal inflammation and pathological RNV in the mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR).

While dyslipidemia and cholesterol accumulation have been strongly implicated in promoting pathological NV in models of subretinal NV15, not much is known about role of cholesterol metabolism, activation of ACAT1/SOAT1, and CE formation in pathological RNV during ischemic retinopathy. More is known about the involvement of the ACAT1/SOAT1 pathway in other diseases. Increased ACAT1/SOAT1 expression/activity in activated macrophages has been implicated in atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer16,17,18. Epidemiological studies and clinical trials have shown a correlation between high levels of plasma cholesterol and diabetic retinopathy19,20. Alterations in cholesterol metabolism have also been shown to induce cholesterol accumulation and formation of hyperreflective cholesterol crystals that impair visual function in the diabetic retina21.

Oxidative/nitrative stress, macrophage activation, inflammation, and pathological RNV

The mouse model of OIR has served as a key experimental tool for elucidating the mechanisms of pathological RNV. In this model, neonatal mice are maintained in hyperoxia from postnatal day 7 (P7) to P12, the time when the retinal vessels are forming, and then returned to normoxia. The hyperoxia environment induces obliteration of the immature vessels and prevents further microvascular development. Because the retinal neurons continue to develop normally during the hyperoxia treatment, the lack of the normal blood supply to the retinal tissue leads to relative hypoxia and promotes pathological vitreoretinal NV when the neonates are returned to normoxia on P12.

In models of OIR in vivo and hyperoxia-treated endothelial cells in vitro, oxidative/nitrative stress has been shown to play a key role in the hyperoxia-induced endothelial cell death22,23. There are several sources of oxidative/nitrative stress in the OIR model, including superoxide and peroxynitrite24. Superoxide formation due to activation of the NADPH oxidase NOX2 isoform together with nitric oxide formation due to increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) have been strongly implicated in retinal vascular injury during OIR and other models of ischemic retinopathy, including diabetic retinopathy and ischemia-reperfusion injury25,26,27,28. Superoxide and nitric oxide react to form the toxic product peroxynitrite, which damages the retinal cells as well as reducing the availability of nitric oxide needed for normal vascular and neuronal function29.

Protein synthesis pathways in the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and nucleus as well as protein turnover pathways are all highly sensitive to ROS-related redox conditions30. Long chain unesterified free fatty acids along with some of their derivatives and metabolites can modify intracellular production of ROS31. Also, oxidative and nitrative stress mediate the activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways and promote induction of the M1-like proinflammatory macrophages during OIR32,33.

Studies in the OIR model have shown a key role of macrophage activation in this pathology. Depletion of macrophages during the relative hypoxia/RNV phase by intraperitoneal injections of clodronate-liposomes reduced retinal macrophage numbers by approximately 80% and significantly inhibited pathological RNV while improving physiological vascular repair34. In contrast, macrophage depletion during the hyperoxia phase did not affect the vaso-obliteration. These findings demonstrated that macrophage depletion markedly decreased OIR severity as well as reducing levels of angiogenic cytokines and extracellular matrix degradation34,35. Studies in the OIR model also have reported a population of M1-like proinflammatory microglia/macrophages localized to the areas of pathological RNV during the relative hypoxia/RNV phase along with activation of the NFκβ / STAT3 signaling pathway and increased expression of inflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL6, and IL1β35,36.

In the OIR model, cells in the ischemic tissue promote pathological RNV by secreting VEGF and other angiogenic factors along with macrophage chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1), and macrophage colony stimulating factor (MCSF1)14,34,37. MCP1/CCL2 is a member of the C-C chemokine family and a potent chemotactic factor that attracts macrophages into the retina where they can release pro-angiogenic factors, promoting the growth of abnormal blood vessels. Once the macrophages are recruited, MCSF1 further activates them, enhancing their ability to produce inflammatory mediators and contribute to pathological angiogenesis10. It has been shown that inhibition of MCP1 decreases RNV38. MCSF1 secreted by macrophages, is required for the differentiation of resident macrophages and microglia during development39. Inhibition of MCSF1 selectively suppresses tumor angiogenesis and in contrast to VEGF blockade, MCSF1 inhibition does not promote rapid vascular regrowth10,40. Our studies in the OIR model have shown high levels of MCSF1 expression in the areas of pathological RNV41. Because macrophages can secrete MCSF1 as well as respond to it, our results suggest a proangiogenic role of MCSF1 released by activated macrophages as well as an additive effect of macrophage proliferation on pathological RNV.

TREM1 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1), inflammation, and pathological RNV

TREM1, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, has emerged as an important enhancer of inflammation. It activates neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages through the adapter protein DAP1242. TREM1 can be induced by several stimuli including hypoxia43,44 and may act as a stimulating factor for neuroinflammation. When activated in models of ischemic stroke or traumatic brain injury, TREM1 directly activates spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and its downstream signaling cascades in microglia45,46. This induces a proinflammatory microglial phenotype that can lead to neurotoxicity. Our studies in the mouse model of OIR have shown that hypoxia robustly increases expression of TREM1 together with MCSF141. We also have found that TREM1 is localized to immune cells positive for isolectin B4, Iba1, CD45, and to MCSF1 positive immune cells in areas of pathological RNV. Moreover, specific inhibition of TREM1 blocked the pathological RNV and improved physiological vascular repair. This was the first study to show that TREM1 plays a major role in the progression of RNV in mice with OIR and suggested that activated microglia/macrophages are the main source of TREM1 expression41.

Dyslipidemia and TREM1 activation

Lipids are a major building block in all living cells. They are involved in a wide variety of structural and functional cellular processes. More than 50% of the brain’s dry weight is composed of lipids, which are found as phospholipids, sphingolipids, glycerol lipids, fatty acids, and sterols, with phospholipids accounting for ~ 50% of total lipid content47. Functionally, lipids are key components of cell membranes including neuronal synapses and myelin sheaths. Within cell membranes they can serve to transduce signals to regulate a range of biological processes and in some circumstances act as bioenergetic fuels48. In these processes cholesterol esterification is a physiological mechanism used to store and transfer cholesterol in order to maintain cellular homeostasis and avoid cellular toxicity due to excess levels of unesterified cholesterol (also called free cholesterol)49.

Studies in models of atherosclerosis have demonstrated a synergistic interaction between dyslipidemia and activation of TREM1 in myeloid cells that leads to increases in production of proinflammatory cytokines50. Furthermore, hypercholesterolemia was found to induce TREM1 expression in myeloid cells and to subsequently increase myeloid cell differentiation, thereby increasing monocyte development and promoting proatherogenic cytokine production and foam cell formation. Pharmacological blockade of TREM1 in the db/db and high fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse models of type 2 diabetes has been shown to inhibit accumulation of lipid droplets, reduce inflammatory damage to hippocampal neurons, and improve cognitive functions51.

ACAT1/SOAT1 (Acyl-coenzyme A: Cholesterol Acyltransferase 1/ Sterol O-Acyltransferase 1) and RNV

ACAT/SOAT are microsomal membrane-bound enzymes that are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. They use cholesterol and long chain fatty acid as substrates to produce cholesterol esters (CE)52. ACAT/SOAT enzymes are expressed in many tissues including brain, retina, liver, and other tissues, where they are involved in formation and accumulation of CE16,53. In mammals, ACAT/SOAT exists as two isoforms: ACAT1/SOAT1 and ACAT2/SOAT2. Most tissues express ACAT1/SOAT1 as the major isoform and ACAT2/SOAT2 as a minor isoform54. Both isoforms are allosterically activated by their substrate (cholesterol or oxysterols). Cholesterol activates ACAT1/SOAT1, induces its expression allosterically, and is more effective than other sterols in this effect.

High levels of ACAT1/SOAT1 activity have been shown in a variety of disease conditions, including cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and cardiovascular disease55,56,57. Studies using macrophages have shown that internalization of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol by the LDL receptor and the resulting increases in intracellular cholesterol levels increase ACAT1/SOAT1 activity which leads to increases in CE formation58. Our studies in the OIR mouse model have shown that increased expression of inflammatory mediators and pathological RNV are associated with increased expression of LDLR, increased accumulation of neutral lipids, and elevated levels of CE in areas of RNV along with high expression of ACAT1/SOAT159. ACAT2/SOAT2 expression was unchanged during OIR. The ACAT1/SOAT1 protein was colocalized with TREM1, MCSF1, and markers of macrophage and microglial cells in areas of pathological RNV. Consistent with these findings, recent lipidomic analysis showed marked elevation of cholesterol esterification, lipid droplet formation, reversed cholesterol transport, and increased concentration of n-9 fatty acids along with increased expression of ACAT1/SOAT1 in the OIR retinas at P17 as compared with the room air controls60.

Our studies further showed that deletion of the LDL receptor completely blocks pathological RNV which indicates a critical role of LDL cholesterol uptake in the pathology59. Moreover, treatment with the specific inhibitor of ACAT1/SOAT1 K604 during the relative hypoxia phase of OIR significantly inhibited the increases in inflammatory mediators and limited the pathological RNV while reducing the avascular area, indicating involvement of CE formation in the pathology. Also, OIR-induced increases in retinal ACAT1/SOAT1 expression/activity together with high levels of CE formation and accumulation of neutral lipids were associated with increases in the expression of VEGF. In contrast with the effects of K604 treatment in reducing signs of inflammation and limiting the pathological RNV, VEGF expression was not affected59. Our studies using microglial cells exposed to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) under in vitro conditions further showed marked increases in expression of ACAT1/SOAT1, TREM1, and MCSF along with significant increases in expression of VEGF59. Treatment with the K604 ACAT1/SOAT1 inhibitor blocked each of these effects except for the increase in VEGF expression.

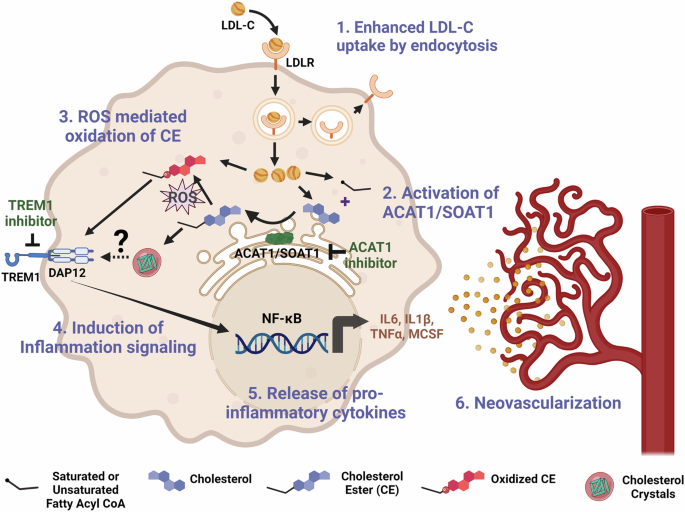

These data suggest that the increase in VEGF expression in the models of OIR or OGD is independent of ACAT1/SOAT1 activity. Although intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF are often used to treat RNV, potential side effects can limit its use4. VEGF is a critical survival factor required for physiological vascular growth and repair61,62. In our OIR study we also observed increased numbers of tip cells sprouting into the avascular area of retinas of OIR mice treated with K604 and a reduction in the avascular area as compared with the vehicle treated ischemic retinas. This suggests that inhibition of ACAT1/SOAT1 can limit pathological RNV while preserving normal VEGF expression and thereby promoting physiological vascular repair. This strategy may offer an effective therapy for pathological neovascularization. Figure 1 illustrates a suggested signaling pathway involved in ACAT1/SOAT1-induced RNV.

1) Enhanced LDL-cholesterol uptake: Under hypoxic/ischemic conditions, macrophages/microglia show increased expression of LDL-receptor (LDLR) and increased internalization of LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C). 2) Activation of ACAT1/SOAT1: Hypoxic/ischemic conditions promote increased cholesterol uptake along with increased ACAT1/SOAT1 activity which increases CE formation. 3) ROS mediated oxidation of CE: Ischemia induces ROS formation, which leads to CE oxidation (Ox-CE) via activation of radical and nonradical modification pathways69. 4) Induction of Inflammation signaling: Ox-CE can activate TREM1 through TLR459,68. TREM1 induces inflammation by activating the DAP12/Syk (spleen tyrosine kinase) signaling cascade. TREM1 inhibition decreases levels of inflammatory cytokines65. 5) Release of proinflammatory cytokines: The nuclear factor-κB (NFκβ) signaling pathway is induced by TREM1, which leads to the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL6, IL1β, TNFα, MCSF41,70 6) Retinal neovascularization: Activated macrophages/microglia play a key role in regulating angiogenesis and are critically involved in the pathogenesis of RNV. Created in BioRender. Zaidi, S. (2025) BioRender.com/c38e697.

Dyslipidemia, macrophage activation, and inflammation

Our studies have implicated ACAT1/SOAT1 activity and CE formation in the OIR-induced increases in expression of LDLR and TREM1 along with MCSF1 as well as inflammatory cytokines [59]. We and others have shown that TNFα is involved in pathological RNV, breakdown of the blood retinal barrier, and ACAT1/SOAT1 expression59,63,64. The mechanism of hyperlipidemia-induced macrophage activation and the role of TREM1 in the process are not fully understood. While several endogenous ligands for TREM1 have been identified, the mechanism of their activation is still not clear65.

One possible mechanism may involve activation of the toll like receptor 4 (TLR4)-Syk pathway. In a macrophage model of dyslipidemia, activation of TLR4 has been shown to play a key role in ROS formation. Stimulation of peritoneal macrophages with minimally modified LDL cholesterol (mmLDL) has been shown to promote significant increases in NOX2-derived ROS leading to increases in expression of inflammatory cytokines66. This effect was completely blocked in TLR4 knockout mice. In contrast, macrophages from MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary response protein) knockout mice showed a normal ROS response. This suggests that mmLDL cholesterol-induced NOX2 derived ROS production in macrophages depends on the presence of TLR4 but not MyD88. Also, LDL cholesterol-induced activation of TLR4 in macrophages has been shown to involve TLR4-mediated Syk activation and downstream signaling. J774 macrophages stimulated with LDL cholesterol showed increased coimmunoprecipitation of Syk with TLR466. In a recent study using microglial N9 cells, it was found that blocking ACAT1 with K604 significantly reduced the proinflammatory responses induced by LPS. K604 decreased the total TLR4 protein content by promoting TLR4 endocytosis, which enhanced the trafficking of TLR4 to the lysosomes for degradation. This suppression of TLR4 resulted in the inhibition of its proinflammatory signaling cascade in response to LPS67. The mechanism of this effect is as yet unknown, but may involve ACAT1/SOAT1 inhibitor-induced alterations in TLR4 membrane microdomains that cause it to undergo an increase in caveolae-mediated endocytosis.

Another likely mechanism is that oxidized CE could be involved. Studies have shown that oxidized cholesteryl arachidonate with bicyclic endoperoxide and hydroperoxide groups (BEP-CE) works as a specific oxidized CE to activate macrophages in a TREM2/MD2 (myeloid differentiation factor 2)-dependent manner68. MD2 is a TREM2 binding protein that dimerizes with TLR4 and is required for TLR4 activation. BEP-CE induces TLR4/MD2 binding and TLR4 dimerization which promotes phosphorylation of SyK, ERK1/2, JNK and c-Jun, cell spreading, and uptake of dextran and native LDL cholesterol by macrophages68. Taken together, these results suggest involvement of different sources of free radicals in the process of beta oxidation of LDL cholesterol which converts CEs into active forms capable of activating other enzymes or inducing the expression on other proteins. More studies are needed to fully elucidate the TREM1/TLR4/ SyK signaling pathway in ischemic retinopathy.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated a novel strategy to limit pathological RNV and promote physiological repair in the mouse OIR model by inhibiting ACAT1/SOAT1 activity and thereby preventing CE formation and blocking activation of TREM1. The mechanism behind hypoxia-induced inflammation and macrophage/microglia activation is not yet clear. Our studies in the OIR model have shown that LDLR is induced by hypoxia and that LDLR deletion completely blocks intravitreal RNV59 which strongly supports the role of LDL cholesterol uptake in the pathology. In the OIR model, inhibition of ACAT1/SOAT1 significantly reduces inflammation and inhibits pathological RNV while improving vascular repair without altering VEGF expression. Anti-VEGF therapy during ischemic retinopathy is associated with some risks of neurovascular dysfunction since VEGF is a survival factor required for retinal neuronal function and vascular repair, especially during OIR. Collectively, dysregulation of retinal lipid metabolism in ischemic retinopathy can impact a variety of factors involved in inflammation and neurovascular damage and therefore visual functions. In summary targeting ACAT1/SOAT1 activity offers a novel strategy for treatment of ischemic retinopathies and other diseases that involve pathological RNV.

Limitations and future directions

Under normal conditions ACAT1/SOAT1 is important for a variety of homeostatic functions, particularly in relation to immune function. However research in models of Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular disease has shown that excessive CE formation leads to the activation of myeloid cells and subsequently to cellular damage and that this can be blocked by inhibiting ACAT1/SOAT1 activity55,56,57. While the mechanism of this protective action is not fully established, results of studies using a model of LPS-induced neuroinflammation suggest that this protective effect involves alterations in the caveolae/lipid raft region of the plasma membrane67.

The above mentioned work in Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular disease models has shown that blockade of ACAT1/SOAT1 can limit disease pathology without impairing normal physiological functions. However considering that neonatal mice are undergoing normal development, we monitored body weight, motility, behavior, and plasma levels of cytokines and lipid profiles after treatment with the ACAT1/SOAT1 inhibitor or vehicle control. Those analyses showed no adverse effects with the inhibitor treatment. Our data further showed that inhibitor treatment over a period of 10 days inhibits pathological RNV and promotes physiological vascular repair while limiting vision loss tested after the mice mature. In comparison with anti-VEGF, the ACAT1/SOAT1 inhibitor treatment should be safer since blocking VEGF affects all cells that require it for their normal function including neurons as well as vascular endothelial cells.

In our study we did not identify subtypes of CEs. Their identification will be key to defining more clearly the role of CE in this pathology. To access this, correlating a lipidomic analysis with studies of the expression of ACAT1/SOAT1, TREM1, MCSF1, VEGF and inflammatory cytokines should be a priority. Our further studies will explore the known markers of retinal neuronal damage, including vascular permeability, leukocyte adhesion, acellular capillary formation, retinal inflammation, and oxidative stress in relation to the tissue damage induced by ACAT1/SOAT1 in models of diabetic retinopathy (i.e., Akita mice, STZ-induced diabetic mice, db/db mice). Studies using strategies for deletion of ACAT1/SOAT1 in macrophage and retinal microglial cells will give us a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

Responses