Human adipose depots’ diverse functions and dysregulations during cardiometabolic disease

Introduction

Obesity, with its negative impact on cardiometabolic diseases, is a major and growing global health issue. Understanding underlying mechanisms that could be targeted is therefore important. Fat storage in adipose tissue can during energy excess be expanded to extreme measures, a condition known as obesity. However, less visible is the dysregulation and loss of adipocyte function that accompanies obesity to various extent in an individualized manner. Adipose tissue is commonly divided into white, beige and brown adipose tissue. However, when discussing distinct adipose functions, these terms are incomplete. Adipocytes exist as different subtypes and have specialized functions, which are largely separated by their anatomical organization into adipose depots. Importantly, adipocytes are even found to have distinct functions within depots, displaying a wide heterogeneity at single cell resolution1. Analyses of human cohorts, discussed below, suggest that there is a fundamental connection between adipocyte functionality and cardiometabolic health.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that hip to waist ratio or waist circumference is a far more accurate predictor of cardiometabolic disease than body mass index (BMI)2,3. Accordingly, abdominal obesity is associated with a reduction in adipogenic capacity (i.e. the capacity to form new adipocytes) in the subcutaneous adipose tissue depot, in primarily the gluteofemoral region4, and a reciprocally increased lipid storage and increased low grade inflammation in the visceral adipose depot5,6. At the same time, cardiometabolic disease is also associated with a loss of thermogenic activity in the supraclavicular and deep neck7. Thus, adipose tissue across depots is functionally compromised during cardiometabolic disease.

The explanation for what is causing adipocyte loss of specialization during cardiometabolic disease and whether it is causative or a consequence, remains elusive. Genetic predisposition8 and genetic interaction with environmental factors including diet, stress, smoking, sleeping patterns and infrastructures discouraging physical activity and generating unhealthy eating patterns, are all contributing to a physiological challenge of excess lipids and glucose that will affect us differently dependent on genetic make-up.

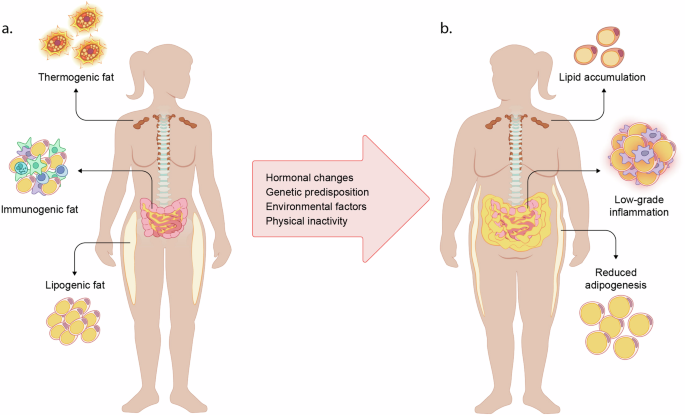

In the current review, we will not discuss genetic and environmental interactions, but instead focus on the differential dysregulations occurring in each of three major adipose tissue depots that have most frequently been studied in relation to cardiometabolic disease (Fig. 1): supraclavicular/ deep neck brown adipose tissue (BAT), omental visceral adipose tissue, and gluteofemoral subcutaneous adipose tissue. We will discuss adipose depot-specific dysregulations and consequences across depots that can contribute to the progression of cardiometabolic disease.

In a healthy state (a), thermogenic fat (brown adipose tissue) is sympathetically activated in response to cold, producing heat and taking up glucose and fatty acids from the circulation. In the visceral depot, immunogenic fat interacts with the immune system to battle inflammation and infections. Subcutaneous adipose tissue is highly lipogenic and provides safe energy storage. Several factors including hormonal changes, genetic predisposition, environmental factors and physical inactivity, contributes to metabolic dysfunction (b). Thermogenic depots lose their capacity of substrate uptake and thermogenesis. Ectopic fat is accumulating in the visceral adipose depot, accompanied by a chronically inflammatory state. Subcutaneous adipocytes reach their maximal capacity of fat storage and adipogenesis is downregulated, diminishing the potential of safe lipid storage and accelerating ectopic fat accumulation.

Dysregulation of thermogenic and immunogenic functions in visceral adipose tissue

Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is a collection of adipose depots surrounding the inner organs. These include the intraperitoneal depots (omental and mesenteric), which drain into the hepatic portal vein. It also includes the retroperitoneal, which is located behind the abdominal space, in the peritoneal cavity where the perirenal adipose depot is found. Whereas perirenal fat is classified as a brown adipose depot9 and has been frequently observed as activated along with supraclavicular and deep neck regions10, omental and mesenteric fat are not thermogenic under normal conditions. Nevertheless, thermogenic adipocytes have been detected at least in the omental fat among other adipocyte subtypes when the tissue has been studied at single cell resolution11,12. This aligns well with the observation that the whole visceral compartment can differentiate into highly thermogenic fat during pathological conditions such as pheochromocytoma (tumor leading to overproduction of norepinephrine from the adrenal gland)13. As discussed in further detail below, thermogenic adipocytes become dysfunctional during cardiometabolic disease7.

The omental adipose tissue has immunogenic capacity and interacts with the immune system during abdominal inflammation. Interestingly, adipose progenitors isolated from omental adipose tissue display a more immunogenic transcription profile and commit less to adipogenic differentiation compared to subcutaneous adipocytes14. The limited adipogenesis in cells from the omental depot is further emphasized by differentiating adipose progenitors from the visceral depot having a lower proportion of adipogenic cells compared to cells isolated from subcutaneous, supraclavicular and perirenal depots, when analyzed at a single cell level15. In vivo, the omental depot is highly vascularized and appears to play an important part in mobilizing the immune defense against pathogens as well as during non-infectious inflammation16,17. During these conditions, the omental fat relocates to the affected area and encapsulates it. A dramatic increase in immune cell number has been observed in the omentum attaching to the inflamed and/or infected site18. During obesity- induced cardiometabolic disease, an expansion of ectopic fat storage in the visceral depots typically occur19. This fat accumulation is associated with a chronic low-grade inflammation20, hallmarked by increased infiltration and residency of pro-inflammatory immune cells into the adipose tissue. Importantly, inflammatory cytokines including TNF have inhibitory effects on adipogenesis14, and an inflamed adipose tissue can thus impair healthy adipogenesis and further accelerate ectopic fat storage. Whether this increased ectopic fat storage in turn hampers the capacity of omental adipose tissue to react properly to infection and regulate inflammation remains largely unexplored. In conclusion, human visceral adipose tissue during healthy conditions, encompasses thermogenic and immunogenic capacities, which are both dysregulated during cardiometabolic diseases in favor of lipid storage, inactivate thermogenic capacity, and onset of low-grade inflammation. The reason behind ectopic fat storage in the visceral depots might be related to a dysfunctional subcutaneous adipogenesis, expansion and signaling in response to excess energy intake, which is further discussed below.

Exhaustion of subcutaneous adipose tissue and loss of adipogenic capacity

In humans, subcutaneous fat has no contact with inner organs and has evolved to exhibit an extraordinary capacity of safe energy storing. Fat accumulation in the gluteofemoral subcutaneous adipose tissue has been identified as particularly healthy and associated with insulin sensitivity4. Insulin stimulates lipogenesis and plays an important role in adipogenesis21. In accordance, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes are associated with premature adipose cell senescence along with reduced adipogenesis22,23,24. The reduced adipogenic capacity is in turn associated with increased adipocyte hypertrophy24, which correlate with elevated plasma insulin levels and reduced insulin sensitivity25.

Another important regulator of adipogenesis is estrogen which appears crucial for maintenance of the gluteofemoral subcutaneous adipose tissue26. In women, estrogen promotes adipogenesis specifically in the gluteofemoral depot due to higher expression of the estrogen receptor in the gluteofemoral adipose progenitor cells27, while inhibiting fat accumulation in visceral regions28. This relationship is emphasized by the body fat redistribution occurring during menopause when estrogen levels decrease29. In accordance, women’s cardiometabolic health falls drastically following menopause30.

Additional observations emphasize subcutaneous adipose tissue as a gate keeper of cardiometabolic health. For example, a compensatory increase in visceral fat mass has been observed 6 months after liposuction of subcutaneous adipose tissue31. Moreover, patients suffering from lipodystrophy, failing to store fat in subcutaneous depots, exhibit both visceral fat mass expansion and increased cardiometabolic burden32.

Whereas safe lipid storage is a key function of the subcutaneous adipose tissue, a loss of functional adipocytes is likely also affecting the adipokine signature, which represent a crucial feedback mechanism for regulating food intake, reviewed in detailed elsewhere33.

In conclusion, preserving functionality and sustained safe storage capacity of free fatty acids in the subcutaneous adipose depot is fundamental for avoiding ectopic fat accumulation in the visceral regions. Individual capacity for expanding subcutaneous adipose tissue before reaching adipose tissue exhaustion and dysregulation is a possible explanation to why obesity is not always leading to cardiometabolic disease.

Loss of thermogenic function in brown adipose tissue during cardiometabolic disease

Humans are among the mammals that still possess the capacity of activating thermogenesis through mitochondrial uncoupling protein 134,35. This occurs via sympathetic activation in response to cold, mainly in adipose tissue in the supraclavicular and deep neck region, along the spinal cord and in the perirenal adipose tissue surrounding the kidneys10. When adipose progenitors are isolated from surgical biopsies from these regions, they differentiate into thermogenic brown adipocytes in vitro, regardless of the thermogenic in vivo phenotype9,36. However, in vivo this function is gradually declining with age and even more severely and rapidly with cardiometabolic diseases7. Thermogenic activity was found to be reduced with obesity, while fat accumulation in brown adipose tissue (BAT) was higher compared to BAT of normal weight subjects10. Importantly, in larger cohorts, BAT activity correlates with insulin sensitivity and cardiometabolic health independently of BMI7. Whether this correlation represents a functional role of BAT in the maintenance of a healthy metabolism in humans, is currently unclear.

In mice, diet-induced obesity increase BAT inflammation, promotes white adipocyte infiltration, distorts BAT function, and inhibits tissue glucose uptake37, while BAT transplantation from healthy wild type mice into ob/ob mice improves insulin sensitivity and counteracts hepatic steatosis38. In fact, increasing BAT activity in mice directly counteracts obesity. Nevertheless, considering the differences between mice and humans in lipid storage capacity, thermogenic capacity and metabolism, it is difficult to directly translate these observations to humans. Given the smaller proportions of BAT present in humans in comparison to mice, there is likely an alternative explanation to its correlation with cardiometabolic health.

First, the gold standard for measuring BAT activity in humans is through FDG-PET/CT-scanning, measuring the glucose uptake in BAT during cold exposure as an estimate of BAT activation39. With an increased lipid accumulation in BAT, it is possible that the glucose uptake is severely reduced. Another potential explanation is altered batokine secretion pattern. Brown and white adipose tissue secrete metabolic regulators33,40. Thus, regardless of whether adult humans have enough BAT to significantly affect energy expenditure through cold exposure, BAT might still play a role in regulating metabolic homeostasis in human through organ crosstalk41,42. In conclusion, the correlation between reduced BAT activity during cardiometabolic disease, how this relates to the overall dysfunction of other adipose depots, and how it impacts whole body metabolism remains to be explored.

Concluding remarks and perspectives

We here discuss the loss of adipocyte specialization in three major adipose depots in humans and how this relates to the development of cardiometabolic disease. Expansion of the visceral adipose tissue, accelerating low-grade inflammation, is a key driver of insulin resistance. At the same time, losing adipogenic and storage capacity in subcutaneous depots and thermogenic capacity in BAT, will accelerate lipid deposition in the visceral depot. Indeed, emerging reports about futile cycling, reviewed elsewhere43 demonstrate capacity for energy dissipation in adipose depots other than BAT as well. In addition, loss of adipocyte specialization should be expected to also affect adipocyte subtype secretomes, potentially causing disturbances in whole body energy homeostasis. Future studies should investigate depot-specific regulation of adipocytes in relation to metabolic phenotypes for discovering new pathways and candidates with the ultimate goal of reversing cardiometabolic disease and reinstall adipose tissue as a functional regulator of metabolic homeostasis.

Responses