Incretin-based therapies for the treatment of obesity-related diseases

Introduction

From 2000 to 2019, the Global Burden of Disease study showed a 0.48% annual increase in age-standardized disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) related to obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 1. A further increase by 39.8% in obesity-related DALYs and by 42.7% in obesity-related mortality is expected from 2020 to 20301. DALYs and mortality related to obesity are the consequence of the multiple comorbidities spanning from cardiovascular (CV) and metabolic diseases, such as heart failure (HF) and type 2 diabetes (T2D), to many cancers, infertility and respiratory (e.g., obstructive apnea syndrome), cutaneous (e.g. psoriasis) and psychosocial conditions (e.g., depressive syndrome)2,3. Even though some individuals with excess adiposity might be relatively metabolically healthy compared to others with a similar BMI, they may still be considered at risk for obesity-related primarily non-metabolic complications (e.g., osteoarthritis, gallstones, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease)3. Unsurprisingly, it has been estimated that healthcare expenditure of European countries for overweight, obesity and related comorbidities might require approximately 8% of total national budgets between 2020 and 20504.

Lifestyle interventions, mostly aiming at diet and physical activity improvement, represent the foundation of obesity treatment, yet an escalation to pharmacological and/or surgical interventions is often needed5. So far, bariatric surgery has proven to be the most effective approach to body weight (BW) reduction, as a recent network meta-analysis demonstrated that it was associated with a 17.7% greater BW loss compared to lifestyle intervention/medical therapy6, with substantial improvements or remission of T2D, dyslipidemia and hypertension7. Moreover, the Swedish Obese Study showed that bariatric surgery was associated with decreased CV and cancer mortality by 30% and 23%, respectively8. Surgical management is indicated for patients with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with ≥1 obesity-related complication or BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, even though less than 2% of eligible patients actually receive this treatment9. Pharmacological interventions are indicated in patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 in the presence of ≥1 obesity-related comorbidities10. These drugs have been designed to tackle the multiple pathogenetic pathways underlying weight gain, mostly aiming to reduce energy intake by affecting appetite and satiety10. Orlistat, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, and the incretin-based drugs liraglutide and semaglutide, both GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), and tirzepatide, a biased dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist, are currently both FDA and EMA approved for the management of non-syndromic obesity10. The unique pharmacological profile of tirzepatide allows a greater engagement of the GIP receptor, mimicking the actions of native GIP, compared to the GLP-1 receptor, where it activates biased downstream signals favoring cAMP generation over beta-arrestin recruitment, resulting in reduced receptor internalization and degradation2.

A network-meta-analysis showed that phentermine/topiramate and semaglutide were the most efficacious therapeutic options in terms of BW reduction11. However, lacking trials conducted with tirzepatide, an updated comparison among available anti-obesity medications (AOM) is warranted. Mirabegron, a beta3-adrenoceptor agonist, is currently under investigation as an alternative strategy to achieve weight loss by inducing browning of subcutaneous white adipose tissue and increasing energy expenditure; however, initial small human studies have been disappointing12. Also, evidence from patients with T2D showed that SGLT-2 inhibitors could provide benefits in terms of BW loss and reduction of both visceral and subcutaneous fat; however, their effects are modest13,14 and did not support their further development for the management of obesity in the absence of diabetes.

To date, incretin-based approaches for obesity management appear as the most promising and rapidly developing (Supplementary Table 1), with innovations such as once-weekly (OW) injectable triple GIPR/GCGR/GLP-1R agonist retatrutide (LY3437943), cagrilintide (long-acting amylin analogue)/semaglutide 2.4 mg (CagriSema) combination, GCGR/GLP-1R dual agonists, high-dose oral semaglutide, and oral non-peptide GLP-1 receptor agonist orforglipron, with relevant implications in terms of patients’ compliance and environmental sustainability.

Efficacy and effectiveness of incretin-based therapies in body weight reduction

Randomized controlled trials (RCT)

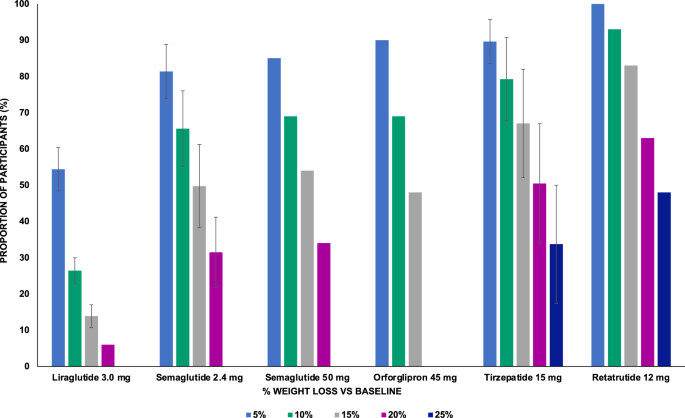

Liraglutide, titrated up to 3.0 mg administered subcutaneously once daily (OD), was the first incretin-based AOM to be developed and launched on the market. Evidence of its weight-lowering efficacy was accrued in the dedicated SCALE (Satiety and Clinical Adiposity Liraglutide Evidence) program. In four randomized controlled trials (RCT) conducted in patients with obesity without T2D15,16,17,18, liraglutide 3.0 mg was compared to placebo as an adjunct to lifestyle optimization over 56 weeks, with the exception of the 3-year extension of the SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes study. This study was limited to the subgroup of patients with prediabetes with the primary aim to assess the proportion of individuals who developed T2D18. Participants were mostly white female adults (mean age 45–49 years), with a mean BMI of 37.5–39.3 kg/m2 10. In the SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes trial, 61% of participants had prediabetes17, while the prevalence of baseline prediabetes was not stated for the SCALE Maintenance16,17 and SCALE IBT15 trials, and participants’ mean HbA1c was 5.5%. At 56 weeks, patients on liraglutide 3.0 mg lost on average 6.1–8.0% of BW vs. 0.2–4.0% on placebo15,16,17, with the extension of SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes suggesting a slight weight regain after the first year18. Liraglutide 3.0 mg was also beneficial in reducing BW in adolescents with obesity compared to placebo (−3.2% vs. 2.2%)19. Weight loss was also assessed in the SCALE Sleep Apnea RCT, in which 359 non-diabetic individuals (mean age 48.5 years, mean BMI 39.1 kg/m2), mostly males with untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), were enrolled to investigate the effect of liraglutide on disease severity20. Patients on liraglutide lost 5.7% BW at 32 weeks compared to 1.6% for those on placebo20. The SCALE program also included two RCT conducted in patients with T2D on background oral anti-diabetes medications with21,22/without22 insulin, aiming to assess the efficacy of liraglutide 3.0 mg on weight loss at 56 weeks. These studies confirmed the weight lowering efficacy of liraglutide in this setting, showing a BW change ranging from −6.0% to −5.8% with liraglutide compared to −2.0 to −1.5% with placebo21,22. Across the SCALE trials, the proportion of patients losing >5%, 10%, 15% and 20% of BW was 46.3–63.2%, 22.8–33.1%, 11.0–18.1%, and 6.0%, respectively (Fig. 1), with a mean reduction in waist circumference (WC) ranging from 4.7 to 9.4 cm15,16,17,18,20,21,22.

In randomized controlled trials investigating multiple doses of the experimental medications, results obtained with the highest dose were reported. Standard errors are not shown for data retrieved from a single study. Liraglutide 3.0 mg was administered subcutaneously once daily (refs. 11,12,13,14,16,17,18,26); Semaglutide 2.4 mg (refs. 20,21,22,23,24,26,27,28), Tirzepatide 15 mg (refs. 30,31,32,33) and Retatrutide 12 mg (refs. 35) were administered subcutaneously once-weekly; Semaglutide 50 mg (refs. 36) and Orforglipron 45 mg (refs. 37.) were administered orally once daily.

The development program of semaglutide 2.4 mg, STEP (Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity), consistently suggested an even greater BW lowering efficacy compared to SCALE23. The double-blind multicenter phase 3 trials STEP 1, 3, 4, 5 were conducted in adults (mean age 46.2–47.3 years), mostly females, with obesity or overweight with ≥1 weight-related complication (mean BMI 37.8–38.4 kg/m2) and aimed to demonstrate the superiority of semaglutide 2.4 mg over placebo in BW lowering at 68 or 10424 weeks as an adjunct to diet and physical activity23. Of note, in STEP 3 intensive behavioral treatment was also administered in both arms, and in STEP 4 all patients were initially assigned to semaglutide 2.4 mg but were randomized 2:1 to semaglutide 2.4 or placebo after 20 weeks25. In STEP 1 and STEP 3, patients on semaglutide lost 14.8–16.0% BW compared to 2.4–5.7% in the placebo group at 68 weeks26,27. STEP 5 yielded very similar results (−15.2% vs. −2.6% with semaglutide 2.4 mg and placebo, respectively) at 104 weeks24. In STEP 4, all participants lost on average 10.6% BW at 20 weeks; those continuing on semaglutide 2.4 mg achieved a 7.9% BW reduction at study end, while patients on placebo exhibited a BW gain of 6.9%25. The efficacy and safety of semaglutide 2.4 mg was also assessed in patients aged 12–17 years with a BMI >95th percentile or a BMI >85th percentile with ≥1 weight-related comorbidity in the STEP TEENS trial, producing similar results (−14.7 vs 2.7% weight change with semaglutide 2.4 mg vs placebo, respectively)28. Moreover, a post-hoc analysis of the STEP 1 trial confirmed the consistency of the semaglutide 2.4 mg weight-lowering potential regardless of baseline BMI < 35 kg/m2 and comorbidities29.

The open-label STEP 8 trial compared the efficacy of liraglutide 3.0 mg and semaglutide 2.4 mg at 68 weeks in 338 participants with overweight or obesity and baseline characteristics coherent with previous STEP trials, confirming the superiority of semaglutide (−15.8% vs −6.4% with semaglutide and liraglutide respectively, p < 0.001)30. A blunted BW reduction was observed in patients with T2D in the STEP 2 trial (−9.6% vs −3.4% with semaglutide 2.4 mg and placebo, respectively)31 and in East-Asian patients with overweight or obesity with/without T2D32. Across the STEP trials, the proportion of patients losing >5%, 10%, 15% and 20% of body weight was 68.8–88.7%, 45.6–75.3%, 25.8–63.7%, and 13.1–39.6%, respectively (Fig. 1), with a WC mean reduction ranging from 6.4 to 14.6 cm24,25,26,28,30,31.

Tirzepatide has been recently added to incretin-based AOM. RCT conducted in patients with T2D showed that high doses of tirzepatide represent the most efficacious incretin-based anti-diabetes drug in terms of BW reduction33, sustaining the development of the SURMOUNT program to explore its efficacy and safety in the management of obesity9. The SURMOUNT program is composed of multicenter double-blind RCT evaluating the efficacy and safety of OW tirzepatide compared to placebo on top of dietary and physical activity recommendations in patients with obesity or BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 with ≥1 weight-related complication9. SURMOUNT 1, 3 and 4 enrolled patients without diabetes, aged 44-48 years, mostly females, with a mean BMI of 38.0–38.6 kg/m2. The proportion of participants with prediabetes was 40.6% in SURMOUNT 134 while it was not reported in SURMOUNT 335 and 436, enrolling patients with a mean HbA1c of 5.5%. In SURMOUNT 1, tirzepatide induced a mean BW reduction of 15.0%, 19.5% and 20.9% with 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg, respectively compared to 3.1% obtained with placebo at 72 weeks34. Similarly, SURMOUNT 3 showed a mean BW reduction of 18.4% with tirzepatide titrated to the maximum tolerated dose (15 mg for 86% participants) after a 72-week follow-up35. In SURMOUNT 4, all participants received the maximum tolerated dose of tirzepatide for 36 weeks and were then randomized 1:1 to continue tirzepatide or receive placebo until 88 weeks. Patients assigned to tirzepatide showed a 20.9% BW loss after 36 weeks with an additional 5.5% reduction after 52 weeks, while those who switched to placebo experienced a 14% weight regain, confirming the findings from STEP 4 supporting the chronicity of obesity and the need for continuous treatment. Confirming the findings from previous trials, the tirzepatide weight-lowering efficacy was still impressive yet blunted in patients with T2D, as shown in the SURMOUNT 2 trial. The study population had a mean age of 54 years and a mean BMI of 36.1 kg/m2 and experienced a BW reduction of 12.8%, 14.7% and 3.2% with tirzepatide 10 mg, tirzepatide 15 mg and placebo, respectively, at 72 weeks37. BW change was also a secondary outcome of the SURMOUNT OSA38 and the SYNERGY-NASH trial39. The former enrolled 469 non diabetic obese individuals aged 47.9–51.7 years with moderate-to-severe OSA (mean BMI 38.7–39.1 kg/m2) and showed a 17.7–19.6% BW reduction with the highest tolerated dose of tirzepatide vs. 1.6–2.3% with placebo at 52 weeks38. The latter enrolled 190 patients with obesity (mean age 54.4 years, mean BMI 36.1 kg/m2) and biopsy-proven MASH and moderate-to-severe fibrosis regardless of the presence of T2D, showing a BW reduction of 10.7%, 13.3%, 15.6% and 0.8% at 52 weeks with tirzepatide 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg and placebo, respectively39.

Across the SURMOUNT trials, the proportion of patients losing >5%, 10%, 15% and 20% of body weight was 79.2–97.3%, 60.5–92.1%, 39.7–84.1%, and 21.5–69.5%, respectively34,35,36,37; notably, 9.0–54.5% of patients lost >25% of initial body weight36 (Fig. 1). Treatment with tirzepatide induced a mean WC reduction ranging from 10.8 to 18.5 cm15,16,17,18,20,21,22. A recent network meta-analysis of RCT comparing incretin-based drugs for the management of obesity in non-diabetic subjects supported the superiority of tirzepatide in achieving a greater percentage of BW loss compared to semaglutide 2.4 mg and liraglutide 3.0 mg (−5.13%, 95% CI −9.82 to −0.68, tirzepatide 15 mg vs. semaglutide 2.4 mg; −13.02%, 95% CI −17.44 to −8-57, tirzepatide 15 mg vs. liraglutide 3.0 mg)40.

A recent phase 2 trial investigated the triple biased GLP-1/GIP/GCC receptors agonist retatrutide (LY3437943) in 338 patients with a mean age of 48 years and BMI of 37.3 kg/m2 without diabetes (prediabetes in 36% participants) showing BW and WC reduction ranging from −8.7% to −24.2% and −6.5 cm to −19.6 cm in the 1 mg and 12 mg dose groups, respectively, at 48 weeks41. CagriSema 2.4/2.4 mg is currently under investigation in several trials dedicated to obese patients (NCT05567796, NCT05996848, NCT05813925), including one highly anticipated head-to-head study vs. tirzepatide (NCT06131437). Of note, a small phase 2 study demonstrated that CagriSema 2.4/2.4 mg significantly reduced BW in individuals with T2D and overweight or obesity vs. semaglutide and cagrilintide42. The OASIS 1 phase 3 RCT demonstrated the superiority of oral semaglutide 50 mg vs. placebo at 68 weeks in 667 patients with a mean age of 50 years, mostly females, with a mean BMI of 37.5 kg/m2 and dysglycemia in 8% participants (BW reduction −15.1% vs. −2.4%, respectively)43.

Orforglipron, a non-peptide GLP-1 receptor agonist, represents another daily oral incretin-based AOM displaying dose-dependent BW and WC reductions at 36 weeks ranging from −9.4 to −14.7% and from −9.6 cm to 13.6 cm with the 12 and 45 mg dose, respectively, in mostly female (59%) patients with a mean age of 54.2 years and BMI 37.9 kg/m2 44. Cotadutide (MEDI0382) is the most extensively developed dual GLP-1/glucagon receptor agonist, showing significant improvements in glucose control, BW (likely mediated by reduced energy intake rather than increased energy expenditure), hepatic fat, and albuminuria in a small RCT on patients with T2D and overweight or obesity45,46. Encouraging results have also been reported with mazdutide (LY3305677) in terms of BW, blood pressure (BP), glucose and lipid lowering47, and efinopegdutide (MK-6024) in terms of liver fat content in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) with or without T2D48. Specifically, the only RCT aiming to investigate the BW lowering efficacy of mazdutide in patients without T2D was limited to Chinese patients and referred to different cut offs for the definition of obesity (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2)49. Awaiting further studies to evaluate their efficacy in patients with obesity without diabetes, these compounds will not be discussed further in the present review.

Real-world studies

A recent review of real-world studies (RWS) by Ahmad et al. described an overall poor compliance to AOM, with patients on liraglutide displaying a greater adherence compared to orlistat, phentermine/topiramate, and naltrexone/bupropion50. The majority of RWS conducted in patients initiating incretin-based AOM were retrospective51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 and included liraglutide users, while only a few studies investigated semaglutide titrated up to 2.4 mg65,66,69,70,71 (Tables 1 and 2). Most RWS were burdened by a relatively small sample size and lack of thorough information regarding adherence to treatment and average dose used. Averagely, follow-up duration was approximately 6 months. As in RCT, participants were mostly adults (mean age 30.4–55.5 years) and females (60–95%) with class II obesity, except for studies conducted in China and South Korea, enrolling patients with a mean BMI ranging from 30.8 to 33 kg/m2 53,54,62,66. A minority of studies were exclusively dedicated to patients experiencing weight regain following metabolic surgery64,69,72, which represented an exclusion criteria for most RWS. Most studies included a certain proportion of participants with prediabetes (2.5–52.0%). Similarly, patients with type 2 diabetes were also represented in many studies51,53,54,56,57,59,62,63,65,68,69,70,71.

Mean body weight reduction with liraglutide titrated up to 3.0 mg ranged from 2.3 to 12.3 kg, while patients on semaglutide up to 2.4 mg experienced a mean body weight reduction ranging from 8.2 to 15.8 kg. The percentage of patients losing >5% body weight ranged from 39.6 to 77.2% with liraglutide and 85.7 to 93.0% with semaglutide, while the percentage of patients losing >10% body weight ranged from 14.4% to 30.0% with liraglutide and 47.6 to 64.0% with semaglutide. Only a minority of RWS reported the percentage of patients losing >15% body weight, ranging from 3.5 to 11.3% with liraglutide and from 2.4 to 41% with semaglutide. Most studies did not report changes in waist circumference. Results from studies enrolling patients with previous bariatric surgery are in line with those including surgically naïve individuals64,69,72; furthermore, no difference was detected according to the type of surgery72.

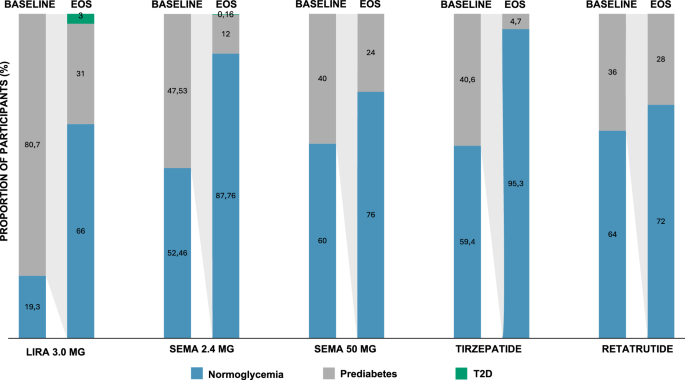

Incretin-based therapy for diabetes prevention in patients with obesity

In agreement with what has been previously shown for any weight-lowering lifestyle intervention and medication, regardless of their mechanism of action18, incretin-based AOM have been associated with amelioration of glucose metabolism and T2D prevention (Fig. 2). In the SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes trial and its extension, treatment with liraglutide 3.0 mg reduced the proportion of patients with prediabetes compared to placebo at 56 weeks regardless of baseline glycemic status (7.2 vs. 20.7% and 30.8 vs. 67.3% in patients with normoglycemia and prediabetes)17. Liraglutide 3.0 mg was also associated with a significant 79% reduction in T2D risk at 160 weeks (HR 0.21, 95% CI 0.13–0.34)18. As for BW reduction, semaglutide 2.4 mg appeared as even more beneficial on glucose metabolism73. Across STEP 1, STEP 3 and STEP 4, treatment with semaglutide 2.4 mg was associated with a significant ∼30% HOMA-IR reduction73. The proportion of patients developing prediabetes among patients with baseline normoglycemia was 1.1–3.2% and 5.0–10.9% with semaglutide and placebo, respectively73. T2D was reported in up to 1% patients on semaglutide vs. 0.9–3% in those on placebo at 68 weeks73. Moreover, a significantly greater proportion of patients with baseline prediabetes reverted to normoglycemia in the semaglutide vs. placebo group (84.1–89.8% vs. 47.8–70.4%)73. Of note, results from a dedicated trial (STEP 10, NCT05040971) investigating the efficacy of semaglutide 2.4 mg vs. placebo in prediabetes reversal will soon be disclosed. Meanwhile, a post-hoc analysis of the STEP 1 and STEP 4 trials showed that semaglutide 2.4 mg was associated with an approximately 60% reduction of the 10-years risk of T2D according to the Cardiometabolic Disease Staging (CMDS) calculator, regardless of patients’ baseline glycemic status74. In SURMOUNT 1, prediabetes reversal to normoglycemia occurred more often in patients on tirzepatide vs. placebo at week 72 (95.3% vs. 61.9%, respectively)34 and a post-hoc analysis of this trial showed a 60–69% mean 10-years relative risk reduction of T2D development75. Results from the SURMOUNT 1 extension will further clarify the role of tirzepatide on obesity-related metabolic disorders. Similarly, encouraging evidence comes from trials investigating new incretin-based drugs, showcasing a greater proportion of patients with prediabetes reverting to normoglycemia following treatment with retatrutide and semaglutide 50 mg vs. placebo (72% vs. 22%41 and 76% vs. 10%43, respectively).

EOS data refer only to participants with baseline prediabetes. Baseline data for liraglutide 3.0 mg are from SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes (ref. 13), EOS data are from SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes extension (ref. 14). Data for semaglutide 2.4 mg are a mean of the results from STEP 1, 3, 4 (refs. 21,22,23). Data for tirzepatide (ref. 30) and retatrutide (ref. 35) refer to pooled doses. Liraglutide 3.0 mg was administered subcutaneously once daily; Semaglutide 2.4 mg, Tirzepatide 15 mg and Retatrutide 12 mg were administered subcutaneously once-weekly; Semaglutide 50 mg was administered orally once daily. EOS end of study, Lira liraglutide, Sema semaglutide, T2D type 2 diabetes.

Results of RWS are in line with data from RCT. For instance, Wilmington et al. showed that 92.3% and 72.2% participants on liraglutide 3.0 mg achieved remission of prediabetes by 6 and 12 months, respectively68 and Ruseva et al. demonstrated that 57.1% and 70% of patients with baseline diabetes and prediabetes reverted to normoglycemia following treatment with semaglutide 2.4 once-weekly at 6 months71.

To date, remission of T2D has been associated by reduction of liver and pancreas ectopic fat accumulation and restored insulin secretion76. Interestingly, a post-hoc analysis of the Prediabetes Lifestyle Intervention Study (PLIS) suggested that patients achieving prediabetes remission differed from non-responders in improvement in whole body insulin sensitivity, visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and intrahepatic fat rather than insulin secretion upon a similar weight loss76. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying prediabetes reversal following treatment with incretin-based AOM.

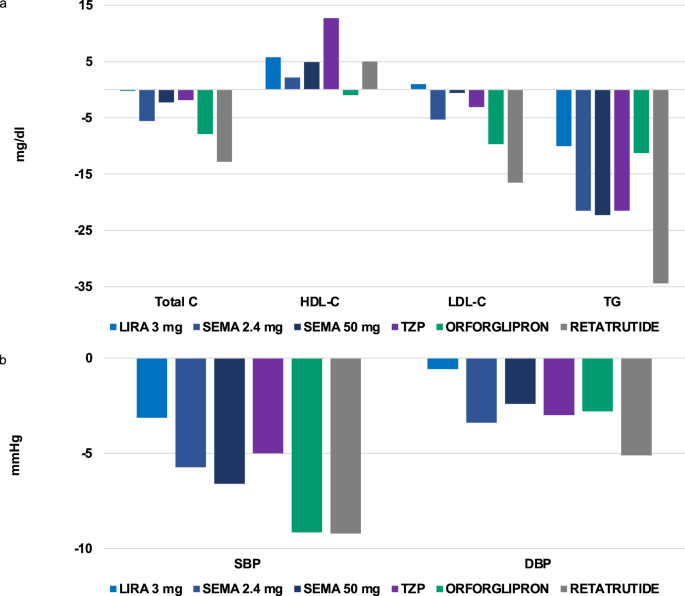

Effects of incretin-based therapy on traditional CV risk factors

Most RCTs with incretin-based therapies reported significant improvements in conventional CV risk factors such as lipids and blood pressure (Fig. 3A, B). Specifically, these drugs consistently induced a reduction in triglycerides ranging approximately from −10% with liraglutide 3.0 mg to −34% with retatrutide. Except for orforglipron, incretin-based drugs appeared to increase HDL-cholesterol up to approximately 13% with pooled tirzepatide doses. Most incretin-based drugs were also beneficial on total and LDL-cholesterol, with the greatest reduction observed with retatrutide (−12.8% and −16.5%, respectively). Systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were also consistently reduced by incretin-based drugs, ranging from −3.1 and −0.57 mmHg with liraglutide 3.0 mg to −9.2 and −5.1 mmHg with retatrutide, respectively. Interestingly, semaglutide withdrawal in the STEP 1 extension was associated with SBP and DBP reversion to baseline levels; also, lipids and C-reactive protein levels increased by week 120, yet maintaining a significant difference with respect to patients on placebo77.

a, b Depict the effect of incretin-based anti-obesity medications on lipid profile and blood pressure, respectively. Liraglutide 3.0 mg was administered subcutaneously once daily (refs. 11,12,13,14,16,17,18,26); Semaglutide 2.4 mg (refs. 20,21,22,23,24,26,27,28), Tirzepatide (refs. 30,31,32,33,38) and Retatrutide were administered subcutaneously once-weekly (ref. 35); Semaglutide 50 mg (ref. 36) and Orforglipron (ref. 37) were administered orally once daily. Data on the effect of Tirzepatide, Retatrutide and Orforglipron were reported for pooled doses. C cholesterol, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Lira liraglutide, SBP systolic blood pressure, Sema semaglutide, TG triglycerides, TZP tirzepatide.

A large patient-level meta-analysis showed that estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline and albuminuria are both associated with increased risk of adverse CV and renal events in the general population78. Indeed, albuminuria and reduced kidney function have been addressed as partially responsible for the residual CV risk persisting despite correction of common CV risk factors79. In patients with T2D, GLP-1RA were associated with a 21% reduction in composite kidney outcomes mostly driven by amelioration of albuminuria80. Likewise, semaglutide 2.4 mg and 1 mg reduced albuminuria by 20.8% and 14.8% and increased the probability of shifting to a lower albuminuria category compared to placebo in the STEP 2 trial79. Most of the beneficial effect of semaglutide on UACR reduction was mediated by HbA1c, BW and BP reduction79. However, no significant difference in eGFR was found in patients treated with liraglutide 3.0 mg and semaglutide 2.4 mg in post-hoc analyses of the SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes, SCALE Diabetes and STEP 1–3 trials79,81. Contrariwise, tirzepatide not only reduced albuminuria but also significantly slowed the rate of eGFR decline compared with insulin glargine in patients with T2D82. The favorable results from the placebo-controlled FLOW trial, conducted with semaglutide 1.0 mg in patients with T2D and chronic kidney disesase (CKD), are about to be disclosed, while ongoing dedicated trials will further explore the effects of OW semaglutide 2.4 mg (NCT04889183) and tirzepatide (NCT05536804) on kidney function parameters in obese/overweight individuals at high risk of CKD progression regardless of T2D.

Effects of incretin-based therapy on CV complications

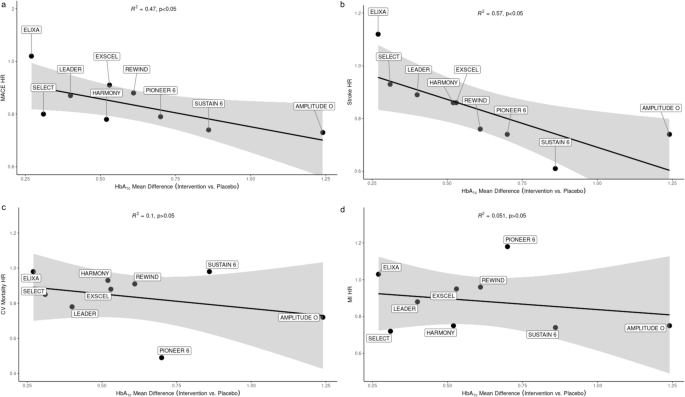

In line with previous evidence accrued in patients with T2D83, recent data demonstrated for the first time that incretin-based therapy was associated with CV risk reduction in patients with overweight or obesity with normoglycemia or prediabetes. Specifically, the SELECT trial demonstrated that OW semaglutide 2.4 mg reduced the risk of major adverse CV events (MACE) compared to placebo (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.72–0.90, p < 0.001) at 39.8 months in patients with preexisting CV disease. Point estimates for MACE components, namely CV death (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.71–1.01), nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.61–0.85) and nonfatal stroke (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.74–1.15), suggested consistent benefit84,85. The population of SELECT was broader (17,605 vs. 3183–14,752) compared to cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) conducted with GLP-1RA in individuals with diabetes, yet similar in terms of mean age (61.6 vs. 59.9–66.2 years), greater male representation (72.3% vs. 54–69%), mean BMI identifying class I obesity (33.3 vs. 30.1–32.8 kg/m2), previous CV disease (99.5% vs. 31–100%), and follow-up duration (3.3 vs. 1.4–6.5 years)84,85. Differently from previous GLP-1RA CVOTs, being conducted in participants without diabetes, SELECT was not designed to achieve glycemic equipoise between arms. However, prediabetes was reported in 64.5% of participants, with a mean (SD) HbA1c of 5.8% (0.3%)86 and, as expected, individuals treated with OW semaglutide 2.4 mg exhibited a greater HbA1c reduction compared to placebo (−0.32%, 95% CI −0.31 to −0.33)84. A meta-regression analysis of CVOTs conducted with GLP-1RA in individuals with diabetes suggested a significant association between reduction in MACE HR and mean between-arms HbA1c difference (R2 = 0.69, p < 0.05), particularly driven by stroke reduction (R2 = 0.89, p < 0.01) rather than non-fatal MI and CV death prevention85. Results from the SELECT trial are coherent with these findings, as mean between-arms HbA1c difference maintains a significant correlation with MACE (R2 = 0.47, p < 0.05) and stroke HR (R2 = 0.57, p < 0.05), while still no association emerged with non-fatal MI (R2 = 0.05, p > 0.05) and CV death (R2 = 0.1, p > 0.05) (Fig. 4A–D). Contrary to expectations86, CV event rate (including stroke) in SELECT was in line with that described in GLP-1RA CVOT conducted in patients with diabetes84,85. This analysis, updated with all GLP-1RA CVOT completed to date, supports the hypothesis that achieving HbA1c lowering with these distinct drugs might be critical for cerebrovascular events rather than MI and CV death risk reduction. The mechanisms sustaining this heterogeneity are unknown, although it should be acknowledged that CVOTs lack the statistical power to reliably detect differences in specific MACE components. Moreover, OW semaglutide 2.4 mg was associated with a consistent benefit in HF composite endpoint, comprising death from CV causes or hospitalization or an urgent medical visit for HF (HR 0.82, 95% CI, 0.71–0.96), and death from any cause (HR 0.81, 95% CI, 0.71–0.93)84. The mean 9.4% BW reduction exhibited by patients treated with OW semaglutide 2.4 mg might partially explain the HF benefit observed in this trial84, as previously demonstrated for treatments leading to at least 10% weight loss87. This finding is not surprising, given the striking association between BMI and HF risk in patients with T2D emerging from the Swedish National Diabetes Registry88. However, the precociously emerging benefit of semaglutide might be explained by several other mechanisms other than BW reduction, such as reduced inflammation and BP lowering84. Treatment with semaglutide 2.4 mg also significantly improved symptoms, evaluated with the Kansas City Cardiomiopathy Questionnaire, and physical limitations, evaluated with the 6 min walking test, in the STEP-HFpEF trial, enrolling 529 patients with obesity and HF with preserved ejection fraction89. A prespecified analysis of this trial showed that a greater weight loss was associated with greater improvements in HF-related symptoms and physical limitations, regardless of patients’ age, gender and baseline body weight89. CV safety is currently under investigation for tirzepatide in patients with obesity without diabetes (NCT05556512) and for cagrilintide/semaglutide with overweight and obesity with and without diabetes (NCT05669755).

The association of mean between-arm HbA1c difference and MACE HR (a) (R2 = 0.47, p < 0.05) is largely driven by reduction of stroke (b) (R2 = 0.57, p < 0.05) rather than CV mortality (c) or MI (d) HR. CV cardiovascular, HR hazard ratio, MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, MI myocardial infarction.

Effects of incretin-based therapy on other obesity-related comorbidities

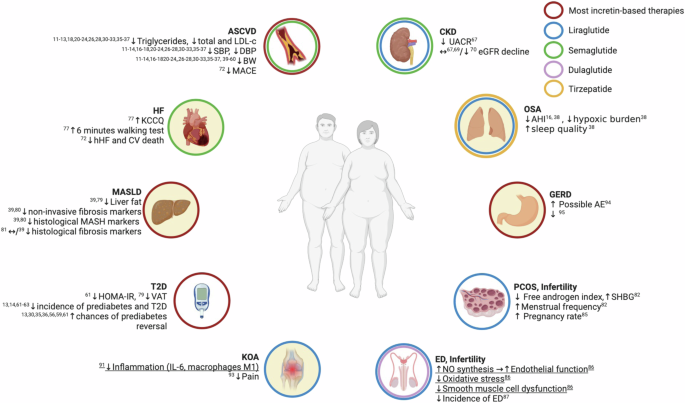

Incretin-based AOM might be beneficial for most of obesity-related comorbidities, notwithstanding their metabolic, load-bearing, and mixed pathogenesis (Fig. 5)3. MASLD, associated with obesity, VAT and liver fat excess and inflammation, is perhaps the most studied among them90. A recent meta-analysis including 30 RCT enrolling 1738 individuals showed that treatment with GLP-1RA reduced VAT (−0.59, 95% CI [−0.83, −0.36], I2 = 77%, p < 0.00001) and hepatic liver content (−3.09, 95% CI [−4.16, −2.02], I2 = 40%, p < 0.00001) with respect to placebo or active comparators regardless of patients’ history of T2D and/or MASLD91. Apart from resmetirom, recently approved by the FDA for use in patients with MASH with moderate to advanced liver fibrosis, there are no other therapeutic options for this disease92. Interestingly, GLP-1RA-based drugs have been proven beneficial to some extent in dedicated trials and should be considered in patients with obesity and/or T2D and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)90.

Summary of the effects of incretin-based therapies on obesity-related comorbidities and their underlying mechanisms according to results of studies conducted in individuals with obesity regardless of the presence of diabetes. AE adverse event, AHI apnea-hypopnea index, BW body weight, CKD chronic kidney disease, CV cardiovascular, DBP diastolic blood pressure, ED erectile dysfunction, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease, HF heart failure, hHF hospitalization for heart failure, KCCQ Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, KOA knee osteoarthritis, LDL-c LDL cholesterol, MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, MASH metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, MASLD metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, OSA obstructive sleep apnea, PCOS polycystic ovary syndrome, SBP systolic blood pressure, T2D type 2 diabetes, VAT visceral adipose tissue. Underlining identifies results from preclinical studies. Red circles, results applicable to most incretin-based therapies; blue circles, results applicable to liraglutide; green circles, results applicable to semaglutide; purple circles, results applicable to dulaglutide; yellow circles, results applicable to tirzepatide; filled circles indicate mostly BW loss-mediated benefits.

The LEAN study was the first to demonstrate that liraglutide 1.8 mg induced histological resolution of MASH compared to placebo in a small group of patients with and without diabetes93. A larger study (SEMA-NASH) enrolling 320 individuals with obesity, biopsy-proven NASH and different degrees of fibrosis, with or without diabetes, demonstrated that OD subcutaneous semaglutide 0.4 mg significantly resolved MASH without worsening fibrosis in 59% of patients93. Both the LEAN and SEMA-NASH trials showed that GLP-1RA slowed fibrosis progression and improved non-invasive markers of fibrosis but failed to demonstrate significant histological modifications93. Secondary analyses of these studies suggested that weight loss might be the main driver of GLP-1RA efficacy in MASH, supported by the lack of expression of GLP-1 receptors in the human liver93. A phase 3 study (NCT04822181), which enrolled 1200 patients with biopsy-proven MASH and fibrosis, is currently ongoing to assess the benefit of OW subcutaneous semaglutide 2 mg in this setting93. Moreover, OW semaglutide 2.4 mg has been recently proven safe and effective in reducing BW, HbA1c and lipids in patients with MASH-related compensated cirrhosis, yet failed to improve fibrosis or induce MASH resolution vs. placebo at 48 weeks94. However, non-invasive markers of disease activity, such as transaminases, gamma glutamyltransferase, pro-C3 levels and liver steatosis at MRI, significantly improved94. In the SURPASS-3 trial, tirzepatide showed an 8.1% reduction in MRI-measured liver fat and AST, ALT and gamma-glutamyltransferase vs. insulin degludec at 52 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes93. Moreover, the SYNERGY-NASH trial showed that tirzepatide was associated with a dose-dependent greater likelihood of biopsy-proven MASH resolution vs. placebo at 52 weeks (62% of participants on tirzepatide 15 mg vs. 10% of participants on placebo)39.

Obesity and metabolic disorders are also commonly linked to reproductive issues such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)95 and erectile dysfunction (ED)96. Several RCT investigated the role of liraglutide, alone or in combination with metformin, in women with PCOS and overweight or obesity, confirming its beneficial effect on anthropometric and metabolic features95; however, changes in menstrual cyclicity and hyperandrogenism were rarely assessed. Available evidence showed that both OD liraglutide 1.8 mg and 3.0 mg were associated with higher levels of SHBG, lower free androgen index and increased menstrual frequency vs. placebo95. Also, in a small study conducted on 60 patients, Xing et al. showed that the combination of liraglutide and metformin improved total testosterone, LH and progesterone more than metformin alone97. Interestingly, preconception administration of liraglutide 1.2 mg and metformin was associated with increased pregnancy rate per embryo transfer and cumulative pregnancy rate in women with obesity in PCOS compared to metformin monotherapy, despite similar weight reduction98. The salutary effects of GLP-1RA on endothelial function could also be exploited for ED amelioration96, as the GLP-1 receptor was detected in endothelial cells and GLP-1RA were found to affect endothelial function by stimulating nitric oxide production99. Evidence on GLP-1 receptor-based drugs and ED are scant and have been mostly accrued in animal models and people with diabetes. For instance, liraglutide improved ED by regulating smooth muscle dysfunction and oxidative stress in a GLP-1 receptor-dependent fashion in a rat model of type 1 diabetes99. The largest study in humans is an exploratory analysis of the REWIND trial, evaluating the effect of dulaglutide vs. placebo on CV outcomes, which showed that dulaglutide was associated with a small yet significant reduction in ED risk (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–0.99, p = 0.021) in 3725 patients with T2D and class I obesity. The same salutary effects mediating MACE reduction by dulaglutide, such as amelioration of glucose control, blood pressure, dyslipidemia, BW and probably endothelial function and oxidative stress, are likely involved in ED prevention and improvement100.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) syndrome is a sleep disorder strongly associated with both the load-bearing and metabolic and inflammatory implications of obesity, leading to increased CV risk and reduced quality of life101. In the SCALE Sleep Apnea RCT, liraglutide 3.0 mg was associated with a significant reduction of apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) compared to placebo (−6.1 events per hour, 95% −11 to −1.2 events per hour) at 32 weeks in patients with moderate to severe OSA not on positive airway pressure20. The clinical benefit of liraglutide 3.0 mg was mostly mediated by its effect on BW, as treatment assignment was not associated with change in AHI independently of weight reduction20. As expected, according to a linear meta-regression model, tirzepatide might decrease AHI in patients with OSA and obesity102. The findings of the SURMOUNT OSA trial supported this hypothesis, showing a significant improvement in AHI, hypoxic burden and sleep quality with tirzepatide compared to placebo at 52 weeks38.

GLP-1RA might also be valuable in knee osteoarthritis (KOA) amelioration, which represents the typical load-bearing complication of obesity and a leading cause of disability and reduced health-related quality of life. Gait abnormalities, modifications of biomechanics and systemic inflammation lead to joint degeneration, pain, and loss of function103. In animal models, intra-articular administration of liraglutide reduced the secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, the expression of inflammatory genes in chondrocytes, the amount of proinflammatory M1 macrophages, and improved pain-related behaviors104. In humans, a RCT enrolling 156 patients with a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 failed to demonstrate that one year of liraglutide treatment could improve pain in patients with KOA compared to placebo, despite a significant BW difference of approximately 4 kg at end of study105. However, the prospective Shanghai Osteoarthritis Cohort study showed that GLP-1RA users with KOA and diabetes exhibited a greater reduction in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) total and pain score and a lower occurrence of knee surgery compared to controls. The latter was mostly mediated by weight loss rather than glucose control106. Further evidence is awaited from the recently completed STEP 9, aiming to assess the efficacy of semaglutide 2.4 mg vs. placebo in terms of weight loss and change in WOMAC pain score at 68 weeks in patients with obesity and KOA (NCT05064735). The double-blind RCT STOP KNEE-OA (NCT06191848) has also been planned to compare the efficacy of tirzepatide vs. placebo in reducing knee replacement risk in patients with obesity and moderate-to-severe KOA.

Of note, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders such as gallstones and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have been identified as mostly non-metabolic complications of obesity and are also listed among possible adverse events (AE) of incretin-based AOM. However, GI AE are usually mild-to-moderate, transient, partially preventable, and rarely lead to treatment discontinuation107. Moreover, GERD amelioration might require ≥10% BW loss, which is hardly achievable and sustainable without pharmacotherapy108.

Treatment adherence

According to a large RWS enrolling 26,522 individuals, new users of liraglutide 3.0 mg exhibited the highest persistence rate compared to patents on other AOM such as naltrexone/bupropion, lorcaserin, and phentermine/topiramate extended release109. However, only 41.8% stayed on treatment at 6 months109, in line with the available literature reporting disappointingly low adherence to liraglutide for obesity management and raising concerns about its role in the lifelong challenge of BW control and weight-related complications110. In a smaller retrospective cohort study, Guy et al. identified older age, higher socioeconomic status, greater initial weight loss, and dietitians support as predictive factors of higher adherence110. In many countries, AOM supply is not granted by the public healthcare service, making affordability an extremely relevant issue for treatment access and persistence. Education level might also be critical to the awareness of long-term obesity implications110. Moreover, response to treatment might be highly heterogeneous; for instance, in the SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes study liraglutide induced a mean weight loss of 8.4 kg with a standard deviation of 7.3 kg111. Female gender, not having diabetes, greater baseline BW and weight loss in the first 16 weeks are potential predictors of better response to treatment112. Further confirmation is required for the role of genotype and central and GI effects of GLP-1RA112. Of note, a mediation analysis of STEP 1–3 trials performed by Wharton et al. showed that less than 1% of semaglutide-induced BW reduction was mediated by GI AE107.

Closing remarks

Incretin-based AOM are currently in the spotlight as the most efficacious weight loss treatment to date113, exhibiting also beneficial effects on the complications of excess adiposity such as T2D, cardiovascular disease, heart failure, MASLD, OSA and possibly others. However, further research is planned to improve our understanding of their effects on obesity-related comorbidities and the underlying mechanism, whether involving direct effects on target tissues or mediated by improvement of adiposity, glucose levels and other CV risk factors. In addition, issues such as adherence, prediction of response to treatment and economic barriers for access to incretin-based AOM will need to be addressed, possibly requiring complex and multifaceted approaches.

Responses