Ketone body metabolism and cardiometabolic implications for cognitive health

Introduction

The alarming rise in cardiometabolic complications of obesity among adults and adolescents places a tremendous burden on healthcare systems1. Obesity increases the risk of all-cause mortality2, mediated in part by heightened potential for cardiovascular complications3, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)4, systemic inflammation5, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)6, and neurodegeneration7. Central to these pathological conditions are the cardiometabolic consequences of aberrant energy production and nutrient storage8, leading to potential disruptions in the regulation of critical cellular processes (reviewed in refs. 9,10,11,12). Specifically, glucose and ketone body metabolism are altered in cardiometabolic diseases13,14, highlighting the importance of substrate metabolism as a factor underpinning poor health outcomes.

Emerging evidence suggests a connection between cardiometabolic complications of obesity and the progression of neurodegeneration7. Supporting this notion are findings suggesting that neurodegeneration is associated with altered brain glucose metabolism15,16 and findings that ketogenic therapies have shown promise in the treatment of neurological conditions associated with neurodegeneration17,18,19. Ketogenic therapies may maintain neurological energy homeostasis, and based on findings in the nervous system and beyond, may confer benefits through mechanisms beyond canonical oxidative roles20. The emerging relationship between cardiometabolic disease and neurodegenerative disorders21 could also be linked through consequences of dysregulated substrate metabolism.

In this review, we discuss the roles of ketone body metabolism and its connectivity with cardiometabolic and neurodegenerative disorders. We highlight both canonical and noncanonical roles of ketone body metabolism in preventing these adverse health outcomes. Since ketogenic therapies have been useful in recent advancements for the preservation of cognitive function22,23, ketone body metabolism may provide valuable insight into mechanistic links that bridge cardiometabolic diseases and the risk for cognitive decline.

Specifically, we cover the following topics:

-

1.

Ketone body metabolism in physiological and pathological conditions

-

2.

Cardiometabolic associations with neurodegeneration and cognitive decline

-

3.

Interventions affecting ketone body metabolism and the effects on complex diseases

Ketone body metabolism in physiological and pathological conditions

The ketone bodies acetoacetate (AcAc), D-β-hydroxybutyrate (D-βOHB), and acetone are primarily synthesized in the mitochondrial matrix of hepatocytes proportional to rates of adipose tissue lipolysis and hepatic fat oxidation. The isoform of 3-hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (HMGCS2) in hepatic mitochondria catalyzes the commitment step of ketogenesis that condenses mitochondrial β-oxidation-derived acetoacetyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA into HMG-CoA, which is then cleaved by HMG-CoA lyase (HMGCL) to produce AcAc. AcAc can be transported into circulation through monocarboxylate transporters (SLC16A1 [MCT1] or MCT2), spontaneously decarboxylated to acetone, or reduced to D-βOHB via mitochondrial D-βOHB dehydrogenase (BDH1) in an NADH-dependent manner. D-βOHB is then transported into circulation via the same transporters (MCT1/2). Once in circulation, ketone bodies enter extrahepatic tissues via MCT1, where D-βOHB oxidation proceeds via reversal of the BDH1 reaction, regenerating AcAc and NADH. Thereafter, AcAc is converted back to AcAc-CoA by the fate-committing mitochondrial enzyme, succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid-CoA transferase (SCOT), which is expressed in all tissues except for hepatocytes and enables extrahepatic oxidation. Subsequently, through mitochondrial thiolase activity, extrahepatic mitochondria generate acetyl-CoA for cellular utilization. In physiological conditions, hepatic ketogenesis increases in response to limitations of carbohydrate availability, such as in fasting or adherence to low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets. Ketogenesis can be further enhanced with increases in energy expenditure or following exercise. Hepatic ketogenesis also increases in pathological conditions, such as diabetic ketoacidosis in individuals with type 1 diabetes, in which unrestrained adipose tissue lipolysis generates fatty acid ketogenic substrates. Hepatic ketone body production and extrahepatic utilization are regulated by insulin and glucagon, with additional control exerted by molecular mechanisms and various transcriptional regulations (reviewed in20).

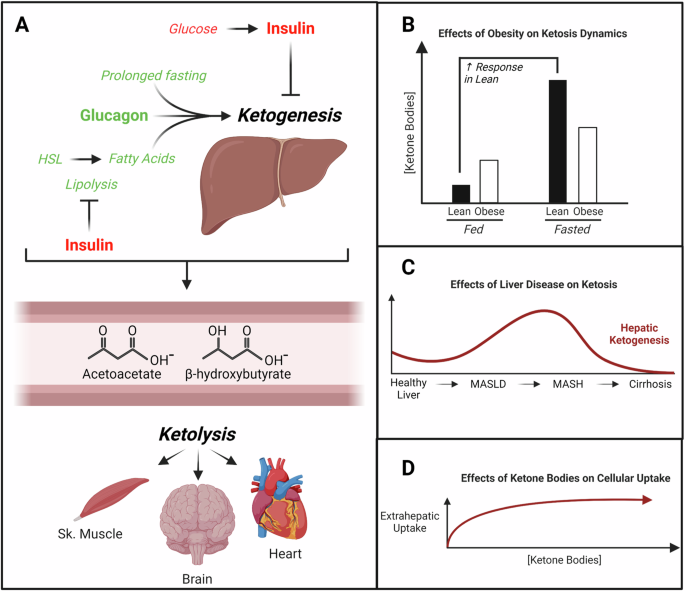

Total ketone body concentrations in circulation typically remain below 250 µM in healthy, fed adults, but can rise to 1 mM following a 24 h fast or approach 20 mM in pathological conditions like diabetic ketoacidosis20. Elevations of endogenously-produced circulating ketone bodies are most often observed in postabsorptive conditions when circulating insulin levels are low and glucagon levels are relatively high24,25 (Fig. 1A). Conversely, increased pancreatic β-cell insulin secretion suppresses hepatic ketogenesis by reducing adipose tissue lipolysis24 and inhibiting hepatic Hmgcs2 transcription through phosphatidylinositiol-3-kinase/Akt signaling26. This suppression of hepatic ketogenesis may also occur through mammalian target of rapamycin 1 (mTORC1)-mediated inhibition of peroxisome-proliferator activated receptor α (PPARα)27. In cases of insulin resistance, higher circulating insulin levels are required to lower blood glucose via tissue uptake and suppression of adipose tissue lipolysis, which triggers hepatic gluconeogenesis. Insulin resistance is the hallmark of cardiometabolic disease, with chronic hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia contributing to aberrant tissue glucose metabolism and altering systemic lipid metabolism (reviewed in28). Thus, in obesity and insulin resistance, which both exhibit elevated fasting and postprandial insulin production, the dynamic range of hepatic ketogenesis is also affected.

Schematic depicting key regulators of hepatic ketogenesis and extrahepatic utilization (A). Hepatic ketogenesis is regulated by levels of circulating insulin and glucagon, with overall capacity influenced by adiposity (B) and the overall rate influenced by liver disease (C) and circulating concentrations (D). HSL hormone-sensitive lipase, Sk =skeletal, MASLD metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, MASH metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Created with BioRender.com

Obesity and insulin resistance are initially associated with compensatory increases in hepatic oxidative metabolism in response to lipid oversupply to the liver29; however, these conditions eventually progress to the accumulation of excess triglycerides in the liver30 that contribute to MASLD. Accumulation of hepatic triglycerides, together with the inhibitory effects of hyperinsulinemia, lead to impaired fasting hepatic ketogenesis31,32,33. Ketosis is less dynamic in obese and insulin-resistant states, as blood ketone levels are typically higher in the fed state due to elevations in lipolysis but lower in fasted states due to hyperinsulinemia, when compared to lean individuals (reviewed in ref. 34) (Fig. 1B). In the setting of hepatic steatosis with insulin resistance, there is greater disposal of β-oxidation-derived acetyl-CoA into the TCA cycle, with augmented gluconeogenic and lipogenic rates that could contribute to reduced ketone body formation35,36. This shift in substrate shuttling not only lowers ketone body production, but it also increases liver lipid storage and glucose production that further drives insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Coupled with hepatic lipid overload, these events promote oxidative stress through chronic, compensatory activation of mitochondrial metabolism31, highlighting an important mechanistic link between obesity and poor health outcomes. These derangements in substrate metabolism additionally contribute to comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and downstream cardiometabolic complications (reviewed in ref. 37). Regulation of ketone body metabolism in normal and pathological conditions is summarized in Fig. 1.

Once in circulation, ketone bodies are transported down a concentration gradient into extrahepatic tissues via MCT138,39. Oxidation of ketone bodies is proportional to tissue uptake40, which is greatest in high energy-requiring tissues such as skeletal muscle, heart, and brain when carbohydrates are in short supply. In rat brain slices, high concentrations of ketone bodies reduce glycolytic flux, and ketone body oxidation becomes the primary contributor to acetyl-CoA generation41. While ketone bodies are efficient substrates for energy provision in extrahepatic tissues42, they can also serve as anabolic substrates for de novo lipogenesis and sterol biosynthesis. In rat models, knockdown of acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase (AACS) lowers blood cholesterol, and in vitro silencing of AACS impairs expression of neuronal markers43,44,45,46,47,48.

Noncanonical roles of ketone bodies were not appreciated until the mid-2000s with the finding that βOHB inhibits adipocyte lipolysis through its binding to the nicotinic acid receptor GPR109A49. Agonism of this receptor by βOHB has also been associated with reductions in the synthesis of growth hormone-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus50 and macrophage-associated neuroprotection51, which could link ketone bodies to salutary changes in brain and neuronal physiology. βOHB also inhibits signaling through GPR41, which leads to reductions in heart rate and overall sympathetic drive52, and further links βOHB to neuronal function. A key set of mechanisms through which βOHB signals is through its ability to regulate histone acylation, including (i) inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) which leads to preservation of histone acetylation53, and (ii) direct covalent modification of histone lysine residues54. In addition, AcAc, but not βOHB, binds the G-protein coupled receptor GPR43 to regulate lipoprotein lipase activity55. This binding specificity of AcAc could be energetically costly by requiring the NAD+-dependent oxidation of D-βOHB, but overall, there is less known regarding the noncanonical signaling effects of AcAc. Nevertheless, the emerging roles of ketone bodies serving signaling roles in the body have sparked increasing interest in therapeutic applications.

Sustained ketosis is associated with diminished extrahepatic expression of SCOT, which catalyzes the fate-committing step in ketone body oxidation56,57,58. Indeed, a paradoxical mismatch may occur between upregulated ketogenesis and diminished ketone disposal that contributes to conditions such as diabetic ketoacidosis. Even so, the pathogenesis of diabetic ketoacidosis is more complicated than this, since patients simultaneously present with hyperglycemia and metabolic acidosis (reviewed in ref. 59). Still, coupling hepatic ketogenesis to extrahepatic ketone body oxidation is critical, because ketone bodies are preferentially oxidized over glucose as a fuel for brain metabolism in fasting patients60. Supporting this notion is the observation that germline SCOT-knockout mice do not survive more than 48 h after birth due to ketoacidosis61. Similarly, humans with bi-allelic loss-of-function mutations in the OXCT1 gene, which encodes SCOT, are susceptible to developing life-threatening bouts of severe ketosis62. Together, these observations underscore the importance of balanced ketone body production and utilization since derangements can lead to severe, pathological consequences.

Cardiometabolic associations with neurodegeneration and cognitive decline

While aging is one of the strongest risk factors for cognitive decline63, observational studies suggest direct associations between cardiometabolic complications of mid-life obesity and the onset of dementia64,65. This implies potential roles of altered glucose and ketone body metabolism in its progression, with the added effects of altered insulin levels likely playing a role. Glucose is the primary fuel source for the brain in the fed state and the brain is a major consumer of the body’s total glucose utilization (>20%) when at rest66,67; however, in periods of low blood glucose, cells within the brain rely on the oxidation of lactate68, ketone bodies60, and to a lesser extent, fatty acids60,69. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that conditions affecting production and/or uptake of these metabolic substrates contribute to neurodegeneration and augmented risk of dementia.

Neurodegenerative diseases share key pathological features with cardiometabolic diseases, with the most notable features being chronic inflammation and insulin resistance70. Central to this link with chronic inflammation is the finding that the adipose-derived pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1β (IL1β), promotes hippocampal neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment71 in mice. The association between adiposity and cognitive impairment might also be mediated through visceral adipose tissue (VAT) inducing the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome72, an intracellular sensor that contributes to onset of neurodegenerative pathology, such as in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)73. Importantly, βOHB inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome74 and could be responsible for the therapeutic potential of ketone bodies on neuroinflammation associated with cognitive impairment. Additionally, secretion of adiponectin, which is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, is inversely associated with levels of VAT75. Adiponectin is an insulin-sensitizing adipokine that can cross the blood-brain barrier to promote cerebral glucose uptake76 and neuronal plasticity in the hippocampus77. Both circulating and hippocampal levels of adiponectin are reduced in obesity78, which could exacerbate poor neurometabolic outcomes. Obesity has been shown to increase neuroinflammation, microgliosis, and amyloid-β deposition in a mouse model of AD79, further highlighting the contribution of obesity to poor brain health outcomes.

While AD is the leading cause of dementia, it remains unclear how cardiometabolic features, like insulin resistance, contribute to its progression. Patients with cognitive impairment show diminished whole-body glucose disposal quantified by a euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp, and increased homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) after fasting80, indicating there is systemic insulin resistance occurring simultaneously with cognitive impairment. Moreover, reductions in cerebral glucose metabolism are also observed in individuals with insulin resistance and prediabetes81, linking cardiometabolic diseases to changes in brain metabolism and cognitive decline. In AD patients, there is a progressive reduction in cerebral glucose uptake and metabolism82, with significant changes in cerebral metabolism observed up to 19 years before AD symptoms manifest83. Thus, insulin resistance may play an important role in the progression of neurogenerative diseases, such as AD.

AD is characterized by progressive neurodegeneration that stems from aggregation of neuronal amyloid-β plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau that forms neurofibrillary tangles (NFT)84. This pathology particularly affects the hippocampus, which is associated with memory formation85. A positive correlation between insulin resistance and the deposition of amyloid-β has been documented in late middle-aged humans86. Insulin resistance in the brain increases phosphorylation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) at Thr668 in AD mice and in rat embryonic cortical neurons87, while diet-induced obesity increases APP levels in the hippocampus of AD mouse models88. Phosphorylation of APP-carboxy-terminal-fragments promotes APP processing and increases production of amyloid-β peptide89, which could accelerate AD pathology. Studies performed in rat hippocampal slices suggest that insulin resistance and APP-induced augmentation of amyloid-β together activate glycogen-synthase-kinase-3β via impaired Akt signaling, which induces hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein in the brain and contributes to NFT formation and memory deficits90. Brain pathology usually correlates with the progression of cognitive decline, but discrepancies between pathological severity and clinical dementia symptoms are not uncommonly reported, as the cognitive reserve hypothesis posits that lifetime experiences, such as education and socioeconomic factors, greatly influence human brain health (reviewed in refs. 91,92,93). Nevertheless, cardiometabolic diseases do reduce cerebral glucose uptake and are directly associated with both neurodegenerative pathology and cognitive decline.

Diminutions in cerebral glucose metabolism, which is observed in AD patients, predicts late progression of dementia better than amyloid-β and NFTs alone94. Overexpression of glucose transporter-1 (GLUT1) in a Drosophila model of AD increases neuronal glucose uptake and simultaneously reduces neurodegeneration95. This implies a critical role of glucose metabolism in maintaining neuronal homeostasis. Isotope tracing studies suggest that in early stages of AD, there may be a compensatory increase in glucose oxidation of cortical, but not hippocampal, neurons96; however, there is progressive reduction in glucose uptake in later stages of AD. Interestingly, the capacity for ketone body metabolism remains intact in the hippocampus of a 5xFAD model97,98, potentially rescuing energy deficits lost to reductions in glucose uptake.

Oxidation is not the only fate of glucose in the brain. Glucose-derived enrichment into the pentose phosphate pathway for de novo biosynthesis of cholesterol, lipids, and nucleotides has been observed in astrocytes from murine, homozygous carriers of E4 for human Apolipoprotein E (APOEε4), a major genetic risk allele for late-onset AD99. Genetic polymorphisms of Apolipoprotein E (APOE), a major lipid-trafficking lipoprotein, modulates the efficiency of systemic lipid transport and fatty acid mobilization100,101 while also influencing cardiometabolic102,103 and cognitive trajectories104,105,106 in humans. The mechanisms by which APOE polymorphisms contribute to cognitive decline likely include reductions in neuronal insulin sensitivity107 and associated metabolic flexibility. Since specific APOE polymorphisms negatively impact lipid metabolism, ketone body metabolism may represent a critical nexus for future studies. Hence, understanding the relationship between the glucose-derived carbon fated for oxidation and for anabolic purposes could illuminate new therapeutic targets for mitigating cognitive decline.

Neuronal energy deficits stemming from impairments of glucose uptake could be resolved with compensatory increases in the oxidation of alternative fuel sources. While ketone bodies have been emphasized in this context, additional studies have focused on the contribution of lactate to brain metabolism and cognition. Elevations in lactate have been detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of AD patients108, and lactate has been reported to support neuronal homeostasis and aid in the recovery of synaptic function following hypoxia109,110. However, increased lactate in the central nervous system (CNS) may be attributable to a relative increased ratio of glycolysis to pyruvate oxidation in the CNS, which could also be implicated in astrocytic-derived supply of lactate to neurons111. Lactate infusion therapies have so far been unsuccessful in the restoration of cognitive function in AD patients112. While increased lactate has been observed in the blood of insulin-resistant patients113,114, lactate infusions may exacerbate insulin resistance115 and may be associated with inflammatory responses in obese patients116. A current clinical trial investigates whether exercise-induced lactate production can modulate brain metabolism, measured with flurodeoxyglucose positive emission tomography (NCT04299308).

There is little known regarding the direct effects of neurodegenerative diseases like AD on hepatic ketogenesis or ketone metabolism in the brain. At rest, AD patients have lower static levels of βOHB within red blood cells and brain parenchyma18, which could imply elevated utilization of ketones, lower cellular uptake, or reduced rates of ketogenesis; however, without tracing studies that measure metabolic turnover and rigorous flux analyses, it is difficult to make meaningful conclusions. Other conditions associated with neurodegeneration, such as spinal cord injury (SCI), promote hepatic steatosis and inflammation117 which correlates with diminutions in hepatic ketogenesis118,119, suggesting that neuronal damage does influence hepatic ketogenesis. Nevertheless, more work is needed to clarify the connection(s) between cardiometabolic diseases and neurodegeneration, as increasing evidence suggests that neurodegeneration is typically a result or exacerbating factor, rather than root cause, of aberrant substrate metabolism.

Interventions affecting ketone body metabolism and the effects on complex diseases

Ketone bodies were initially identified and stigmatized as a pathological biomarker and mediator of type 1 diabetes mellitus120, but the therapeutic potential of ketogenic interventions was first recognized when used as a treatment for medication-resistant epilepsy17. Numerous accounts of ketogenic interventions support the beneficial effects of ketone bodies on cardiometabolic and neuronal health outcomes (summarized in Table 1). In patients with mild cognitive impairment undergoing treatment with low-carbohydrate, high-fat ketogenic diet, the concentration of circulating ketone bodies was positively correlated with memory performance121. While the mechanism(s) by which ketone bodies benefit cognitive function are still unclear, it is important to consider how the duration of ketosis and how the type of ketogenic intervention influences cognitive outcomes. The most common interventions promoting physiological ketosis are a ketogenic diet, exogenous ketone supplementation, exercise, and medications.

Ketogenic diet

Ketogenic diets are high-fat, low-carbohydrate interventions with energy largely derived from fatty acid oxidation, with the spillover of excess acetyl-CoA forming ketone bodies in the liver as glucose reserves are depleted. One effect of the ketogenic diet is an energetic shift from carbohydrate to fat metabolism, which has been postulated to mediate longevity and delay age-related diseases122,123. Ketogenic diets are possibly the most popular method to promote sustained, physiological ketosis and are particularly well-studied in contexts of neurological and cardiovascular diseases. Currently, there are several clinical trials investigating the role of ketogenic diets in neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s (NCT01364545, NCT05469997) and AD (NCT04701957, NCT03690193, NCT03860792), cardiometabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (NCT03652649, NCT04791787) and even heart failure (NCT04235699, NCT06081543) (summarized in Table 2).

Ketogenic diets can be comprised of long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs), medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs), or sometimes both. Ketogenic diets with MCFAs are well-tolerated in AD patients and improve cognitive function22, as do ketogenic drinks that are enriched with medium-chain triglycerides124. Higher levels of ketosis have been reported in ketogenic diets containing MCFAs than LCFAs125. Ketogenic diets increase circulating AcAc and βOHB, which are substrates for ATP synthesis in extrahepatic tissues and have important signaling roles. Acute ketogenic diet interventions (<4 wks) show anti-inflammatory effects in murine adipose tissue through reductions in Nlrp3, IL1β, and TNF-α mRNA expression, but increased inflammatory cytokine expression and accumulation of lipids in the liver126, suggesting there might be temporal or tissue-specific effects. Long-term ketogenic diet (4 mo) in mice is associated with obesity and the depletion of protective γδT cells in VAT127, again suggesting a temporal nature of benefits associated with ketogenic dietary interventions. Because of this, ketogenic diets in biomedical research are sometimes short-term or cyclical, where ketogenic diet alternates weekly with standard chow diet. One study employing a cyclical dietary strategy with ketogenic diet in middle-aged mice found improvements in survival and memory when compared to control diet, without body weight changes, and with the benefits thought to be mediated in part through intermittent upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα)128.

The role of ketogenic diets in neurological diseases is well-reviewed129,130,131, but less is known regarding the utility of ketogenic diets in cardiometabolic diseases linked to cognitive outcomes. Limited studies suggest therapeutic potential in the context of MASLD132,133, while others suggest beneficial effects in obese patients through modulating appetite134, lipogenesis, and lipolysis that could result in weight loss135. Furthermore, ketogenic diets may provide protection against the neurological and cardiovascular complications typically associated with obesity. While ketogenic diets provide many benefits in the short-term, stimulating endogenous ketogenesis through high-fat dietary interventions is also associated with elevations in blood cholesterol136 and possibly poor patient compliance due to tolerance or adverse impacts associated with long-term administration137. Because of this, there is increased interest in other interventions that promote physiological ketosis, such as exercise, fasting, or exogenous supplementation.

Exogenous ketone supplementation

The use of exogenous ketone supplementation and ketone body precursors, such as ketone (di)esters, has increased in popularity since they yield similar benefits as ketogenic diets in a unique physiological state where circulating insulin and glucose concentrations remain normal20. One ketone precursor, R/S-1,3-butanediol, is readily oxidized to D/L-βOHB in the liver138 and can yield physiological ketosis within 2 h of administration139. This could be important in neurodegenerative diseases, since BDH1 is stereospecific to oxidize D-βOHB20 while L-βOHB enantiomer is favored for the synthesis of fatty acids and sterols in the brain140. Interestingly, L-βOHB also binds GPR109A49 and blocks components of the NLRP3 inflammasome74, and has a longer half-life in the circulation than D-βOHB141, and thus might serve keysignaling roles that mediate neuroprotection.

The ketone monoester, R-3-hydroxybutyl R-βOHB, has been extensively studied in humans142,143,144 and rodents145,146, with findings suggesting that this ketone ester can increase circulating βOHB concentration to nearly 6 mM while concomitantly reducing caloric intake, improving insulin sensitivity, and reducing plasma cholesterol. Recently, ketone esters have been useful in lowering body weight147 and improving glucose tolerance in mouse models of obesity148, in addition to improving pathological outcomes associated with MASLD in mice fed a high-fat diet149. In humans, the metabolic effects of increasing circulating ketone body concentrations without the ketogenic diet-induced increase in fatty acids, or hormonal changes associated with these states, remains a growing area of study.

In addition to systemic metabolic benefits, ketone bodies are additionally associated with improvements in neurological and cognitive outcomes. Ketone esters have shown favorable responses in reaction times of athletes following mentally fatiguing performances150, suggesting their utility in acute neuronal processing. Unlike ketogenic diet, supplemental ketosis from exogenous sources inhibits adipose tissue lipolysis and the mobilization of fatty acids typically associated with endogenous strategies151. Administration of exogenous βOHB (sodium salt) inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome and reduced amyloid-β plaque formation in brains of the 5XFAD mouse model of AD18. Another study used exogenous βOHB to protect hippocampal neurons from amyloid-β42 while simultaneously improving cognitive outcomes in an APP mouse model of AD19. Supplementation with ketone esters increases murine hippocampal concentration of D-βOHB and TCA cycle metabolites compared to control diet-fed mice152 and could, therefore, improve energetic efficiency in the brain. However, it remains unclear how exogenous supplementation influences neurometabolism and if there are significant differences in effectiveness comparing acute versus chronic administration.

Exercise

Aerobic exercise leads to coordinated metabolic changes that maintain adequate distribution of oxygen and nutrients in tissues with augmented energy demand. The increase in ATP production is typically met through increased utilization of circulating fatty acids, lactate, and even ketone bodies153. Aerobic exercise has been shown to increase circulating fatty acids and lactate concentrations up to 2.4 mM154 and 10 mM155, respectively, while blood ketone body concentrations have been shown to increase up to 1.8 mM156 in a temporal manner referred to as post-exercise ketosis (PEK). The extent of PEK is typically regulated by training status156, nutrient intake prior to exercise157, biological sex, and exercise intensity158. Given the beneficial effects of ketone bodies on metabolic and cognitive health, a tantalizing hypothesis is that many exercise-induced health benefits could be mediated through elevations in circulating ketone bodies following bouts of aerobic exercise.

Aerobic exercise is known to improve cardiometabolic outcomes related to improving or maintaining insulin sensitivity, effectively lowering insulin levels in insulin-resistant patients and reducing risk for, or effectively treating, MASLD, reviewed in159,160, and may be in part responsible for benefits in cognitive function161,162. Due to the systemic, physiological response to exercise and transient nature of PEK, these beneficial outcomes are likely due to a combination of factors that include emerging “exerkines” such as lactate, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and osteocrin (reviewed in163). Exercise training increases cortical and hippocampal expression of MCTs in rats that could facilitate increased uptake and utilization of ketone bodies164, but the intermittent bouts of physiological ketosis stemming from aerobic exercise may also suggest a temporal requirement of ketosis for ketone-induced benefits. During fasted exercise, skeletal muscle has an augmented capacity for extraction and utilization of ketone bodies, increasing nearly fivefold compared to resting conditions when ketone body concentration remains below 4 mM165,166. Furthermore, while PEK is robustly observed in previously untrained individuals, PEK is attenuated in trained individuals167, likely reflecting ketogenic adaptation for greater skeletal muscle turnover. Still, ketone bodies can have effective signaling roles at concentrations observed in trained and untrained PEK (i.e. < 2.0 mM), such as increases in circulating microRNAs HAS-let7b-5p and HAS-miR-143-3p168, as well as the binding of βOHB to GPR109A49.

Key experiments are still needed to test the requirement of PEK in modulating exercise-induced neuronal benefits and the preservation of cognitive function. In addition, since PEK is transient in nature, there could be therapeutic potential in stimulating repetitive, transient bouts of ketosis on health outcomes. Nevertheless, the role of PEK in mediating metabolic and neurological benefits remains to be fully elucidated.

Medication

Certain medications promote ketosis, which might be an important component that promotes beneficial health outcomes. Emerging pharmaceutical agents that inhibit the sodium/glucose transporter 2 in the proximal renal tubule (SGLT2i), increase urinary loss of glucose, and thus reduce circulating blood glucose while increasing circulating ketone bodies in humans169 through augmented hepatic ketogenesis170. The mechanism by which this occurs is not entirely understood, but attenuated levels of insulin, or enhanced insulin sensitivity, might mediate reductions in plasma glucose and increase glucagon levels to promote mobilization of fatty acids to hepatic ketogenesis171, though this mechanism is debated172. Some of the cardiometabolic benefits associated with SGLT2i include favorable histological impacts in livers of patients with MASLD173,174,175 (comprehensively analyzed in ref. 176), favorable survival outcomes in patients with heart failure174, and reductions in hospitalization for patients with existing cardiovascular and renal disease175. However, those prescribed SGLT2i are cautioned against the risks of potential euglycemic ketoacidosis that may occur if patients concurrently use insulin, are not already significantly hyperglycemic, or have conditions that may additionally elevate ketone bodies177. Still, these agents show robustly beneficial cardiovascular outcomes that may be due, in part, to elevations in circulating ketone bodies178. There are several clinical trials employing the use of various SGLT2i in cardiometabolic conditions (NCT05782972, NCT04014192, NCT05885074), neurological conditions such as AD (NCT03801642), and even a combination of cardiometabolic and cognitive outcomes associated with T2DM (NCT04304261).

Future directions

The obesity epidemic and associated cardiometabolic diseases contribute to many comorbidities that are linked through aberrant metabolic control, with increasing evidence linking obesity and other cardiometabolic diseases to the promotion of neurodegenerative diseases. Central to these conditions are insulin resistance and reductions in cellular glucose uptake, resulting in the reliance on fatty acids, lactate, and ketone bodies for energy balance. Ketone bodies are emerging as being important not only for their energetic efficiency in extrahepatic tissues, but also for non-canonical signaling roles that could mediate many of the beneficial effects of ketogenic therapies.

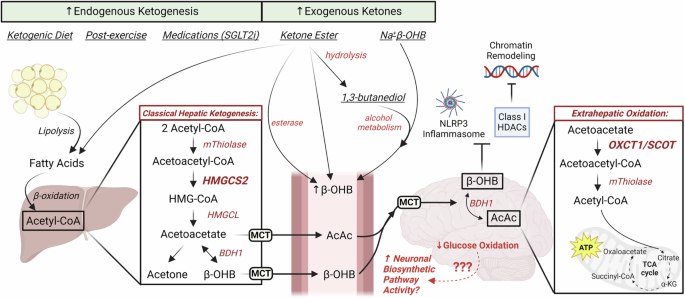

Future studies are needed to fully understand the connections between cardiometabolic and neurodegenerative diseases, with additional work needed to ascertain how ketone body metabolism can be leveraged via exercise, diet, or medications to promote beneficial health outcomes (summarized in Fig. 2). These strategies could begin with personalized approaches to dietary interventions, exercise protocols, and medication usage to take advantage of intermittent or chronic physiological ketosis. Furthermore, while a combination of approaches may prove to be more effective in combating or preventing adverse health outcomes, additional work is needed to ascertain metabolic, mechanistic insights regarding ketone body metabolism that govern complex diseases.

Schematic highlighting the effects of ketogenic diet, exercise, and certain medications (e.g. SGLT2i) on endogenous ketogenesis and neuronal metabolism. Exogenous ketone supplementation includes ketone esters and salts that may increase circulating ketone bodies independent of classical, hepatic ketogenesis. Neuronal uptake of ketone bodies could reduce glucose oxidation and spare glucose-derived carbon for biosynthesis. Created with BioRender.com

Responses