A review of marine genetic resource valuations

Introduction

The ocean has traditionally been a valuable pool of resources, providing food and livelihoods for coastal communities. However, driven by technological progress and a desire to expand economic frontiers as terrestrial resources become strained, recent decades have seen an unprecedented expansion in the scope, scale and diversity of ocean uses1, often with substantial consequences for the functioning of marine ecosystems and well-being of associated communities2,3. One of the more recent and rapidly growing elements of this Blue Acceleration is bioprospecting for marine genetic resources (MGR)4,5.

The marine environment includes a tremendous diversity of ecosystems characterised by extremes of temperature, pressure, darkness, salinity, and hydrochemical compounds. Life has evolved to tolerate and even thrive under such conditions, with these adaptations encoded within the genetic information of species. Consequently, marine organisms have become of interest to a wide range of industries, with their genetic and functional diversity being used as a source of inspiration for applications ranging from the development of new pharmaceuticals all the way to the organisation of complex social systems6,7. Advances in new technologies have also significantly reduced sequencing costs, resulting in the large-scale sequencing of marine genes and, in some cases, even whole genomes8,9. For instance, more than 100 million expressed genes have been sequenced from marine plankton alone10, and a database was published in 2024 including over 317 million unique sequences of marine origin11.

The vast majority of marine genetic sequences used for innovation and discovery are freely available in online databases, the largest of which is the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration that supports deposition of sequences submitted by national patent offices12,13. To date, over 40,000 bioactive compounds derived from marine organisms have been identified and around 7000 are in usage or under validation6,14. Some of these bioactive compounds have been the primary source of novel pharmaceuticals, with compounds from marine species enjoying rates of commercialization up to four times higher than their land-based counterparts15.

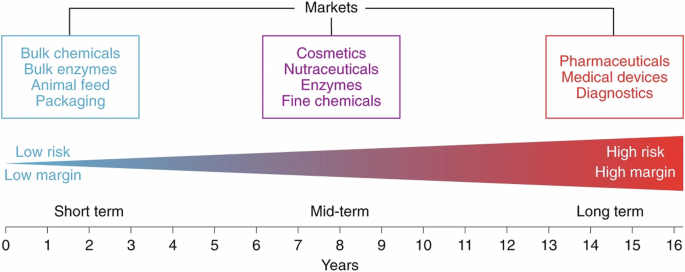

Despite the vast potential and aspirations surrounding marine biotechnology – 75% of the seafloor remains to be mapped at high resolution, and between 70-90% of marine species are still undescribed16,17,18 – assessing its value has proven challenging and controversial19. Historically, efforts to assess the value of ecosystem services or nature’s contributions to people have differentiated between the use and non-use values of nature-derived economic goods. The former refers to the current or future use of a resource while the latter pertains to leaving the resource untapped and intact20. They also separate between direct and indirect contributions and benefits. However, these classifications are not always straightforward in the case of MGR, with commercialization of these resources often taking decades (Fig. 1), and, in some cases, depending only on genetic sequence information rather than a physical sample. In such instances, the use in perpetuity is decoupled from any need for further collection of biological material. By contrast, other biotechnological processes may require MGR to be continuously collected, resulting in direct impacts on ecosystems. Consequently, traditional valuation methodologies that rely on clear separations between direct and indirect use, as well as differentiations of use and non-use values, are difficult to directly apply to MGR-derived biotechnology.

Figure reproduced from Blasiak et al. 15.

Still, multiple efforts have been undertaken to quantify and communicate the value of MGR, and this study provides new insights by mapping these diverse efforts. In particular, it applies the Values Assessment framework that was developed by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)20. In 2012, IPBES was established with a specific focus on improving the interface between science and policy on issues related to biodiversity and ecosystem services, and currently has 145 member states. The IPBES Values Assessment, published in 2022, brought together experts from the IPBES membership and beyond to show “how different worldviews and knowledge systems influence the ways people interact with and value nature”. Drawing on four general perspectives (living from, with, in, and as nature), the framework uses a three-part typology of instrumental, intrinsic, and relational values.

Using the IPBES Values Assessment allows us to broaden the context of critiques of the monetary valuation of ocean resources; some have argued that monetary valuation of nature can help to showcase their benefits to humanity21, while others view the practice as problematic as it fails to represent the many forms of value that can be attributed to nature22,23. Building an understanding of how this debate relates to the valuation of MGR is timely, as multiple international processes are ongoing to determine the specifics of benefit-sharing mechanisms associated with access to and use of genetic resources, with a particular emphasis on their value15,24,25. Equitable outcomes to these international negotiations are of particular interest due to monetary and non-monetary benefits of MGR currently flowing disproportionately to economically powerful states and corporations26.

The paper proceeds by applying the IPBES Value Assessment framework to systematically review existing MGR valuation studies, and identify themes, trends and potential gaps in the literature. It concludes by presenting some challenges as well as opportunities to arrive at more holistic valuations and by considering the broader implications of the valuation of MGR in the context of the Blue Acceleration.

Methods

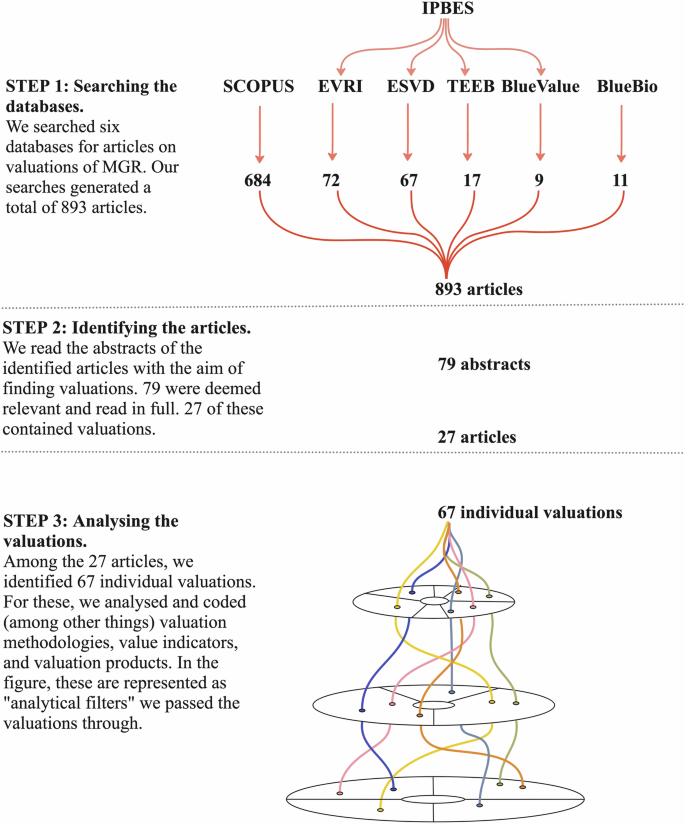

A search was conducted for relevant literature in Scopus and five other databases (TEEB, EVRI, ESVD, BlueValue and BlueBio) to collect MGR valuation studies and their results (Fig. 2). Scopus facilitated the scanning of a broad range of academic articles on the subject, while the other databases enabled a more focused search for explicit valuation work. With the exception of BlueBio, which was encountered in Tassetti et al. 27, all other databases were identified through the IPBES Values Assessment20, and include collections of nature valuation studies. The searches were limited to publications in English, and contained key terms such as “marine genetic resources”, “valuation”, “marine biotechnology”, and “value of”. A full description of search strings and databases is provided in Supplementary Tables S1-S2. While systematic, it was clear from the outset that a comprehensive review would not be possible due to the lack of standardised language on MGR and its diverse values, and because not all studies dealing with valuation explicitly call what they are doing “valuation”. The review thus served as a foundation to identify studies where valuation had been conducted, and to examine how and why this was done.

Databases used for data collection include Scopus, Environmental Valuation Reference Inventory (EVRI), Ecosystem Service Valuation Database (ESVD), The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), BlueValue and BlueBio. All but Scopus and BlueBio were identified through the Intergovernmental science-policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

The initial search generated 893 articles. Among these, 79 articles had abstracts that indicated they contained or could contain valuations of MGR. Two members of the author group jointly conducted the review, analysing different parts of the searches and consulting together on articles for which the categorization was unclear. 825 articles were thus excluded in this first stage because they either (1) did not deal with MGR or benefits derived therefrom; or (2) did not indicate that a valuation had been done or specify a type of valuation product. The 79 remaining articles were then read in full with a focus on identifying the valuations of MGR. This resulted in 27 relevant articles. Some of them only conducted one valuation of a single benefit, while others included multiple valuations. In total, 67 different valuations were identified. Each valuation was coded individually and analysed by registering a series of variables, largely building on the IPBES Values Assessment20 framework but also adding categories specific to the valuation of MGR as well as more general descriptors (Table 1). In addition, for all 27 articles, information was collected about the primary affiliation of all authors and their respective countries.

After registering and coding the valuations, all 27 articles for which a valuation was identified were assessed to understand how the chosen methodology was applied, how the authors motivated the methodology, how they communicated the assumptions they made, and if and how they disclosed the origins of their data and quantifications. This resulted in the identification of challenges associated with the valuation of MGR as well as potential ways forward to build on and complement these existing efforts.

Results and discussion

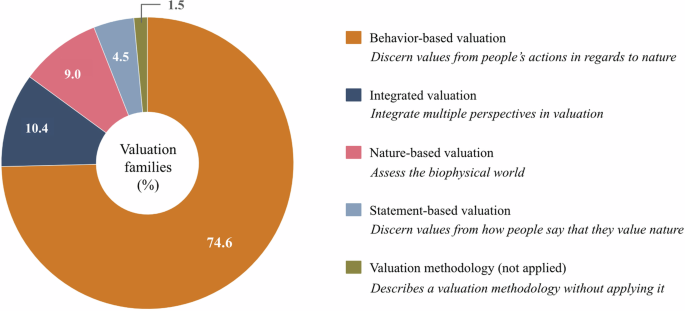

The following section starts by presenting an overview of some of the valuations identified through the literature search (Table 2), which showcases the diversity among efforts to articulate the values of MGR. A full list of the 67 valuations can be found in Supplementary Dataset S1. Figures 3, 4 then show some trends among the material. All four valuation families presented by IPBES20 (behaviour-based valuations, integrated valuations, nature-based valuations and statement-based valuations) were found to be represented in the literature, albeit with uneven distribution (Fig. 3).

The valuation families include behaviour-based valuations, integrated valuations, nature-based valuation and statement-based valuations. One study described a methodology without applying it, and was thus coded as “Valuation methodology (not applied)”.

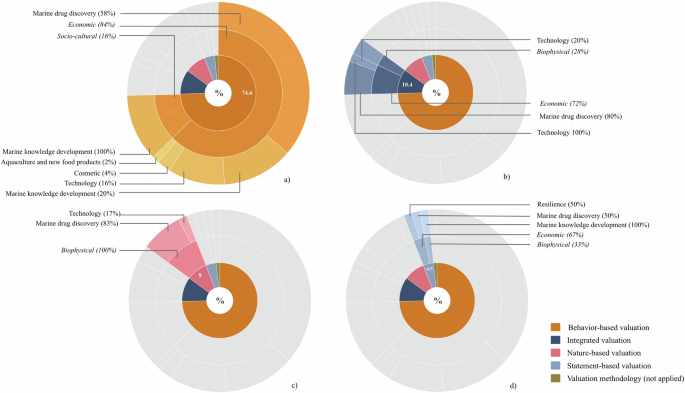

Tier 1 (inner ring), represents the valuation families, Tier 2 (middle ring) the value indicator (written out in italics), and Tier 3 (outer ring) the benefit derived from the marine genetic resource. a Behaviour-based valuations, b Integrated valuations; c Nature-based valuations; and d Statement-based valuations.

The diversity of valuations

Table 2 presents a sample of the valuations of MGR displaying a great diversity of researchers, disciplines, methodologies, and conclusions. It highlights the tendency to focus on behaviour-based valuations, economic value indicators and benefits related to marine drug discovery. However, it also shows that valuations are conducted for different purposes, such as informing management and policy, supporting economic development, or promoting research and innovation. The specific values in focus also vary widely, ranging from the occurrence and abundance of sea cucumbers in the Red Sea28 to the cost of commercial enzymes in the US29. Yet some valuations do overlap, with e.g. Leary et al. 4 and OECD30 both reporting on the market value of the same herpes treatments, albeit with different phrasings (i.e., “market value of a herpes treatment” and “market value of marine-derived Ara-A and Ara-C”, respectively) (Table 2).

Trends

Although there is considerable diversity among the identified valuations and the values they seek to make explicit (Table 2), there are clear trends in the reviewed literature.

Behaviour-based valuations dominated (74.6%), with the end product commonly being a monetary valuation based on market revenues. These were followed by Integrated valuations (10.4%), Nature-based valuations (9.0%) and, lastly, Statement-based valuations (4.5%), which were only found in two studies. One article31 contained an in-depth description of a methodology that could be used to conduct a monetary valuation of MGR, but the authors did not use it to carry out any valuation. This study was included in the material and recorded as “Valuation methodology (not applied)”, but will not be discussed further. Authors from 27 different countries contributed to writing the 27 studies analysed here, although researchers with affiliations in the UK, Italy, or Japan were the most prominent. The majority of behaviour-based valuations came from studies co-authored by researchers with affiliations in Italy (90%) or Japan (70%) (Supplementary Dataset S1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Among the identified benefits derived from MGR, there was a disproportionate focus on marine drug discoveries across all valuation families. Figure 4 introduces the kinds of benefits derived from MGR represented in each valuation family and the associated value indicator. This is accompanied by a brief description of a valuation from each family (see Table 2 for a larger selection of the valuations and Supplementary Dataset S1 for a complete list).

The literature was dominated by behaviour-based valuations of MGR (Fig. 4a). These valuations were to a large extent focused on marine drug discoveries that had been attributed monetary values through analyses of the market revenues of the derived pharmaceutical products. In the majority of cases (84%), an economic value indicator was used. One example comes from Leary et al. 4, who used market revenue calculations to assess the market value of pharmaceuticals derived from or inspired by MGR. They estimated that cancer-fighting agents derived from marine organisms reached a global value of US$1 billion in 2005, and that a herpes remedy from a sea sponge had a market value of US$50–100 million the same year. However, Leary et al. 4. also point out that there was no centralised database where such information could be found. This remains true today with the exception of an end-product traceability system in Brazil, which controls bioprospecting benefits from the use of genetic resources32. Until multilateral access and benefit-sharing arrangements for the use of MGR and digital sequence information (DSI) are in place globally, data will likely remain either spread across patent offices, research institutions and private businesses or unavailable due to industry secrecy to protect intellectual property. Consequently, commercial activity estimates are frequently based on anecdotal information. Another example of a behaviour-based valuation using economic indicators is Tassetti et al. 27, in which the authors identified €39.7 million of project funding that was going into bioprospecting research in Europe in 2023. On the other hand, Oldham et al. 33 used a socio-cultural indicator – the level of interest in MGR in research and industry as indicated by MGR-related keywords in research publications and MGR-related patent filings – to estimate the potential value of MGR used in marine knowledge development.

In the case of integrated valuations (Fig. 4b), 72% of the studies used economic value indicators to value marine drug discovery and technology, and 28% used biophysical indicators to value technology. One such application was the use of a biomimetic energy modelling algorithm inspired by the foraging behaviour of marine predators to improve a Combined Cooling, Heating, and Power (CCHP) system34. The value presented here is in the form of the percentage of improved exergy efficiency (i.e. how well a system can convert available energy into “useful work”).

Nature-based valuations (Fig. 4c) were all conducted using biophysical indicators, showing the value of marine drug discovery (83%) and technology (17%). For example, Lawrence et al. 28 conducted a species survey in the Red Sea to assess the spatial distribution of different species of sea cucumbers and the corresponding levels of bioactive compounds associated with sampled individuals. The authors identified 22 species of sea cucumbers in the area, which were found to be unevenly distributed and where different subpopulations varied with regard to associated bioactive compounds.

A small number of studies (n = 3) used a statement-based approach (Fig. 4d). Two of these applied economic value indicators to estimate the value of marine drug discovery and ecological resilience respectively, while the third used a biophysical indicator to indicate the value of marine knowledge development. For instance, Jobstvogt et al. 35, used a discrete choice experiment to assess the willingness-to-pay (WTP) of Scottish households for deep-sea conservation in anticipation of potential pharmaceutical discoveries. The authors determined a WTP of £35–38 per taxpayer, which amounted to £88,826,500–96,440,200 in total based on the number of taxpayers in 2020.

Challenges in valuation practice

What value, and for whom?

One challenge in valuation practice lies in articulating what values are considered and for whom. Our results show that economic value indicators are largely dominant (63% of all studies) as opposed to sociocultural ones (only one study). Many of the studies aiming to assess the economic value of MGR or marine biodiversity do so by investigating the revenues generated from the sales of e.g. pharmaceuticals based on bioactive compounds derived from marine organisms4,30. The value of the pharmaceutical in question, and by extension the value of the marine organism it originates from, is then only defined by the associated market revenues, which fail to represent the value of the treatment received by the patients, and in essence the value of the human whose life it improves. This risk of ignoring non-monetary values also applies to other benefits, such as energy efficiency improvement, the use of enzymes in industry, or bioremediation technologies. A related problem is clarifying the meaning of the term “value” itself. Relative expressions such as “high-value”36, “low-value”37, or “added-value”38 are common across the literature but their exact meaning is seldom defined and often inconsistent, which adds confusion to an already complex landscape of MGR valuations.

The origin of the valuation also matters when it comes to whom the value is articulated for. Researchers based in highly industrialised countries account for the majority of the studies covered in this review (Supplementary Fig. S1), and contributions from researchers from a greater diversity of countries might provide novel insights and approaches. Likewise, the IPBES Values Assessment highlights the necessity of acknowledging the diversity of values attributed to nature within valuation efforts if the valuation is to be able to adequately inform nature-related decision-making. Importantly, it also notes the importance of including the diverse worldviews of traditional knowledge holders, and explicitly seeks to capture these within its methodology20.

Finally, over the long term, marine biotechnology is expected to become increasingly focused on genetic sequence data rather than physical samples. While this has the potential to reduce the ecological impacts of physical sampling, there is a risk that it also distances resource users from the ecosystems that provide the resources and could also perversely lead to a lowered funding interest in taxonomic research. If a key motive for investing in basic research is the potential for biotechnological advancement and economic gains, and if future activities in this space rely primarily on existing sequenced information, then will investments in taxonomic research decline?

Accounting for complexity

Defining the value of a marine organism based on the sales of the associated pharmaceutical product presents a problem of attribution (Fig. 5). The bioactive compound derived from the marine organism is only one part of the process; other ingredients, labour, and knowledge are necessary to develop the final product (see e.g. the discussions in ref. 31). Here, a distinction is needed between the primary value of the resource (when collected or in situ), and the derivative value as the samples move to further stages along the biotechnology value chain. Likewise, the bioactive compound belongs to an organism that depends on a broader ecosystem, raising the question of scale, and whether value should ultimately be attributed to the compound, to the species, or to the ecosystem it inhabits. Similar problems have been raised for the valuation of ecosystem services and nature more broadly (see e.g. chapters 3.1 and 3.3 in ref. 20). The value of the pharmaceutical is a whole that cannot easily be broken down into parts.

Horseshoe crabs are considered “living fossils” since they have existed in their current form for around 450 million years. In 1972, a company deposited a patent for the use of the naturally blue blood of horseshoe crabs for immunological testing60. Limulus amebocyte lysate is a substance found in the crab’s blood that reacts with endotoxins, making it useful for detecting contaminants or harmful compounds in drugs. It is also widely used in vaccine testing61. As a result, around half a million horseshoe crabs are caught and bled within the pharmaceutical industry every year, a process that can be stressful and lethal for the crabs, and has therefore been described as both unsustainable and unethical62. The ethical, sustainability and human health implications of this case provide an example of how competing values can make decision-making difficult. The ecological and ethical values related to biodiversity conservation and the intrinsic worth of animals stand against the anthropocentric values of medical testing56. A more holistic valuation method would enable an explicit comparison of these competing values to support decision-making. Likewise, it could help raise awareness and build support for the use of alternatives to horseshoe crab blood61. The Intergovernmental science-policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) Values Assessment provides guidance on methods for considering ethical aspects in public debates and incorporating ethical standpoints into policymaking (see Box 3.3 in ref.20).

Transparency

Valuation attempts face challenges due to a lack of transparency. The market value, sales revenues, and researcher estimates are often inaccessible behind paywalls or simply referred to without providing the methodology or data used39,40,41. Likewise, the private sector does not disclose key information that would help in specifying sales volumes or research and development costs. This lack of clarity creates uncertainty and questions the reliability of most monetary valuations of MGR (also noted by refs. 19,33). The same issues apply to projections of future industry growth42, where there is often a disconnect from the physical basis of these trajectories. For instance, the industry will rely on continued sales of products already on the market, but may also generate new products based on the same genetic material that has already been collected. In other instances, new products may rely on the collection of new samples or may not need physical specimens at all, but rather the DSI that has already been entered into public databases and which is the focus of unresolved regulatory negotiations43. Specifying which practices are projected to increase under different scenarios is essential because each faces unique valuation challenges. For example, if the marine biotechnology segment is projected to grow due to increased deep-sea bioprospecting, valuation efforts should also consider the ecological impacts of sampling sensitive environments44. While current marine science collections and subsequent sequencing efforts are rarely conducted with a primary focus on bioprospecting, such transparency would showcase the importance of taxonomic research for the biotechnology sector and help incorporate non-economic values into industry valuations.

Opportunities: complementing current valuation efforts

As the ocean becomes more crowded, sustainable and equitable management will depend on an integrated understanding of how sectors interact and the tradeoffs, dependencies and synergies that connect them. Simultaneously, assessing the value of the ocean genome is also becoming increasingly difficult. Many states have begun to report specifically on ocean-related economic activities in their national accounts, and the potential of a blue economy to spur development has been articulated around the world45. Recognition is growing that navigating this expanding suite of activities will depend on improved marine spatial planning; the central ambition of the 18 member states of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Economy, for instance, is to ensure 100% sustainable ocean management by 2025. Furthermore, the recently adopted Agreement on Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement) has established for the first time a protocol for sharing benefits derived from MGR from areas beyond national jurisdiction. However, as delegates reminded during the closing of the negotiations, no benefits have yet been shared46, and the development of institutions for fair and equitable benefit sharing will depend on articulating these associated benefits.

Ensuring that marine biotechnology can continue to develop in this increasingly complex space will depend on clearly articulating the value of MGR in a holistic manner5. Below, we build on the identified strengths and gaps in the existing valuation literature to identify opportunities to progressively move in this direction. Importantly, there are a myriad of ways to articulate the diverse values of MGR; the pathways suggested below are just examples of opportunities to address the gaps identified in the previous sections. A cross-cutting theme common to all the following propositions is that they will become most effective and impactful under conditions of increased data availability and transparency.

Rethinking the option values of the ocean genome

In cost-benefit analysis, the option value of a resource is what an individual is willing to pay to maintain it as an asset or a service because they might use it in the future47. While current MGR valuation studies are mostly focused on the use-values of marine genes, better articulating their non-use value could enrich the valuation literature and expand its scope48. For example, one could take inspiration from the methodology of Roa, Navrud and Rosendahl49, who quantified the monetary value of a wetland and showed how considering it would change the cost-benefit analyses for project developments in the area. Likewise, a non-use value of marine ecosystems could be estimated in the context of MGR, leading to greater emphasis being placed on preserving intact habitats that have been sparsely studied (e.g. the deep seabed) or which are expected to contain high levels of unknown bioactive compounds (see below). To put it into the language of the Values Assessment: such a valuation could be conducted either through a nature-based or statement-based methodology to assess the benefits of MGR using economic value indicators. However, this approach still relies on monetary estimates of ecosystem values and “putting a price” on nature (see ref. 22 for a longer discussion), as well as assumptions on prospects of scientific and technological development.

Uncovering capital investments

Another way of quantifying the value of MGR is to study and quantify how much capital is needed along the biotechnology value chain, from the collection of samples to the sale of commercial products. For instance, Tassetti et al. 27 created the BlueBio database which discloses national and transnational EU funding going into bioprospecting. Expanding this type of study to encompass corporate investment could uncover how companies themselves value these resources, and consequently provide a proxy for their expectations of future revenues. This would imply a behaviour-based valuation methodology, applied to assess the economic value corporations attribute to the instrumental benefits of the MGR-based biotechnology they are investing in. Results from such a valuation could be usefully contrasted with levels of investment in other areas of research and development, and investments by other ocean-based industries. Levels of long-term investment are also a reflection of perceived financial risk associated with the research (Fig. 1). Here, there is particularly fertile ground for progress by engaging with the reporting framework developed by the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). Published in September 2023, the TNFD recommendations are aimed at helping corporations and financial institutions integrate considerations of nature into decision-making, and include a framework for reporting on impacts on specific biomes, including marine shelf biomes50. Unlike for terrestrial systems, there is currently no mention of MGR. Future valuation efforts could be geared towards 1) outlining how MGR can be included in the TNFD reporting on dependencies, risks, impacts and opportunities related to the marine shelf biome and biotech industry, and 2) making relevant MGR data available for institutions doing the reporting.

Bioactivity mapping

In both terrestrial and marine systems, mapping biodiversity hotspots has been a common way of valuing nature and informing management and conservation priorities. A complementary nature-based valuation relating specifically to MGR could be bioactivity mapping, namely developing methods to provide comparative predictions of bioactive compounds within different ecosystems or biomes51. This would entail applying nature-based valuation methodologies to discern biophysical values of ecological diversity, which could encompass assessing both instrumental and intrinsic use and non-use values and benefits of MGR. For example, Lawrence et al. 28 highlight that different subpopulations within the same habitat of the same species of sea cucumbers can possess different bioactive compounds. This knowledge shows the value of conserving more than one population of a species as a means to conserve biodiversity, and can help to inform the design of networks of protected areas. The development of predictive models that would systematically support such efforts may still be a distant proposition, but recent efforts in microbial data collection have already yielded an unparalleled magnitude of discoveries in the functioning of marine ecosystems11,52. Paired with the advent of machine learning, these datasets are creating new possibilities to effectively scale this approach and drive greater efforts towards ecosystem stewardship and integrated ocean management53,54.

Moving from value as revenue to value as benefit

As shown by our review of existing valuations, benefits from MGR are most commonly valued using economic indicators. However, not all benefits generated from biotechnological development are monetary20; energy efficiency improvements, GHG-reductions, and better health outcomes for patients are examples of benefits from MGR that are only partially captured with monetary figures. Valuing marine inventions for these benefits rather than only for their revenue can therefore enhance the non-monetary valuation of MGR and highlight the diverse ways in which MGR benefit people. In the case of pharmaceuticals, for instance, this approach would involve studying the number of patients treated with a specific marine-derived pharmaceutical, the dosage administered, and the resulting improvements in health or recovery. It would entail applying nature-based and statement-based valuation methodologies to assess benefits from pharmaceuticals using biophysical and sociocultural value indicators. This perspective broadens the focus from commodification and commercial profits to also encompass the underlying health and well-being benefits provided by these inventions. Similarly, laundry detergents relying on enzymes from marine species enable lower-temperature washing conditions and have the potential to considerably reduce carbon emissions55. Studying these emissions reductions instead of detergent sales profits could likewise shift the value perspective from revenue to benefit. Conceptualising values as benefits for people and the planet can expand the range of value indicators used to describe MGR and enable analysis of how these benefits are distributed among different regions and populations.

Conclusion

Valuations of nature are inherently dynamic since they are associated with people, their cultures, and their perceptions of the world, all of which are diverse and continuously changing. A one-size-fits-all solution is therefore neither likely nor desirable. In this review, we have shown that although there is some diversity amongst studies articulating the values of MGR, the literature remains largely focused on providing monetary valuations of marine-derived pharmaceuticals. Sociocultural value indicators are underrepresented, as are non-medicinal biotechnological applications. This narrows the scope of the benefits described and contributes to a homogenisation of the values of nature that are articulated within research. Furthermore, valuation will need to adapt to the context in which it is undertaken and will consequently not always be directly comparable or applicable across contexts. Lack of comparability should, however, not be considered a hard obstacle to valuation, but rather as an invitation to enhance transparency and reflexivity in research practices. Valuation can make people’s diverse values of nature explicit, but as the IPBES Values Assessment underscores, such efforts cannot and should not aim to make values comparable at any cost20,56. Marine biotechnology represents a relatively recent addition to the rich history of humanity’s interactions with the ocean and its resources. A rapidly expanding understanding of its scope and potential has driven aspirations of future research and development. But ensuring its place within a sustainable blue economy will require considering the many values associated with MGR, marine ecosystems and marine scientific research as a whole, rather than solely focusing on the projected economic value of biotechnological development.

Responses