Is tuna ecolabeling causing fishers more harm than good?

Introduction

A tuna catch equal to half of the world’s supply comes from 49 fisheries in the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) program, which the ecolabel defined as “wild food, good jobs, and healthy oceans” in 20221. The MSC makes assurances in the market about fisheries governed as public resources. As a UK-based charity, it exerts significant influence on market perceptions of sustainability in the fisheries sector See Supplementary Note 12. Its success is demonstrated by its £45 million in assets and nearly £33 million income3,4 from licensing the use of its ecolabel to the wild-caught seafood trade, including tuna harvested from 21 of 23 global tuna stocks. The focus of its Fisheries Standard is environmental, but fishing with forced labour is excluded from its scope as a disqualification requirement (1.1.5, v3.0 2022). In 2022 the MSC announced its policy “aimed at providing transparency and enhancing assurance of the absence of egregious labor practices from fisheries and supply chains that are under assessment or certified to the MSC standards”5 and provided instructions to its ecolabeling clients for self-disqualification (Labor Eligibility Requirements v1.0 2022, See Supplementary Note 2).

The intent of this research was to see how forced labor is being kept out of the certified tuna supply chain by the Marine Stewardship Council in practice. Forced labor is a crime, and mandatory requirements might prevent the inadvertent labeling and promotion of fish made with crime. In other sectors, products made with crime are detected or deterred from the supply chain with mandatory and sector-wide due diligence, for example, companies trading on the London Metals Exchange must participate in the Responsible Minerals Initiative and abide by membership requirements to deter illegal conflict minerals and prove legal and regulatory compliance6 in a very different process than a voluntary private social standard. The MSC has stated that it is “already sending a strong signal by withdrawing certification if fisheries are convicted of forced or child labor abuses” and published a Sustainable Tuna Handbook where it expressed “concerns about the scale of forced labor and human rights issues in tuna supply chains” and that “the best way for tuna buyers to significantly reduce exposure to the above risks [of forced labor] is to choose MSC certified tuna” (2022, page 6).

Fishers’ welfare on vessels currently fishing for ecolabeled tuna is important to look into in light of current controversies over forced and child labor in fishing7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. An estimated 128,000 fishers are trapped in forced labor aboard fishing vessels according to the International Labour Organization (ILO)15. Tuna vessels are active further from shore and represent 42% of all human rights and labor abuse instances in a recent database study of vessels linked to global fish crimes16. Forced labor in tuna fishing is well-publicized17,18,19,20 and the story of how tuna is made of utmost importance due to the large volume of catches, high economic value, and extensive international trade21. According to the Marine Stewardship Council, its data “indicate that well-managed fisheries [in its program] are highly likely to have risk mitigating measures in place”5. Yet it has also said this data is “not for assurance or assessment of fisheries performance” See Supplementary Note 3. The mixed message appears to convey assurance that ecolabeled tuna is not made with forced labor, but without being clear about how this is known, or the data quality.

It is not clear how forced labor is kept out of the certified supply chain because the Marine Stewardship Council Fisheries Standard is not a vessel compliance standard See Supplementary Note 44. Certifiers do not assess vessel operations or workplace conditions. They collect vessel names, but an initial review of vessel data showed certifiers do not necessarily collect identifiers like registration numbers or the names of vessel owners, who are the fishing employers. In this respect, MSC ecolabeling is truly unique from other ecolabels, for example from cobalt for cell phones or cotton for clothing where the conditions and processes in a production facility are assessed to a technical performance standard22. Instead, the responsibility for meeting the MSC Fisheries Standard is assigned to government bodies. MSC certifiers collect and assess information generated by governments (generally fisheries departments). Certifiers do not assess the actions of fishing vessel owners and operators but, if the fishery is certified, do inform them of ‘their right to claim the fishery is a well managed and sustainable fishery’ (7.5.8, General Certification Requirements (2023) v2.6). In that case, the fishing entities gain access to buyers looking for certified fish and an association for their product to the beneficial perceptions arising from the MSC’s assurances in the market. The MSC also earns income through licensing fees.

Vessel-owning companies are legally responsible for workplace conditions, it is important to make clear because employer duties are defined in law23, fishers are their employees2 and the relationship is defined in law24 See Supplementary Note 5. It is important to look into the information behind the assurances that the Marine Stewardship Council has made about tuna, and particularly the details it has collected about tuna vessels, catches, and conditions for fishers because risk-free conditions on fishing vessels are not assured by high-level corporate commitments or voluntary pledges by other entities which, according to the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, “may contribute to the enjoyment of rights but do not offset a failure to respect human rights throughout the operations”25. Vessel owner identities are critical data points because INTERPOL has described how forced labor on fishing vessels can be manipulated by vessel-owning entities in a Purple Notice issued to worldwide police forces in 201926, by recruiting foreign fishers through agents to save costs and securing the fishers’ employment in debt13,14. While at sea fishing for tuna, fishers do not control their work hours or access to food, potable water, documents, wages, first aid, or hospital care. Vessel owners have this control. Forced labor in fishing is widespread, according to the International Labour Organization, because businesses recruit fishers for very low wages to work intensely in hazardous and remote conditions who then experience untended injuries, illness, unpaid or withheld wages, and psychological or physical abuse13.

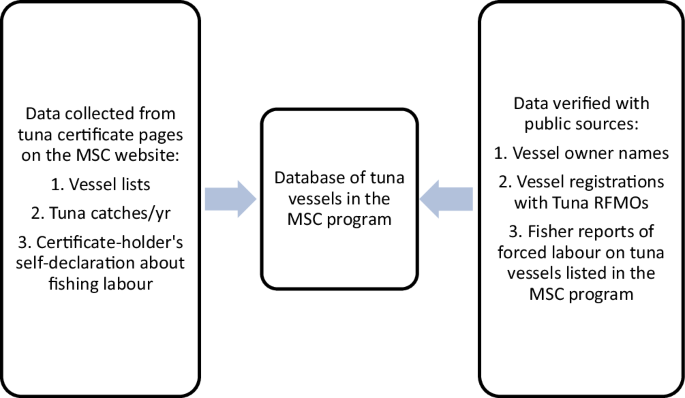

To find out how tuna made with forced labor is being kept out of the ecolabeled supply chain by the Marine Stewardship Council, an analysis was performed of the primary data published by the MSC at https://fisheries.msc.org for the 3327 tuna vessels listed in its program. The research method involved creating a database of the tuna vessels by collecting client information from the dedicated pages for 49 tuna fisheries that were either certified or had made it through the MSC’s Labour Eligibility Requirements and were in the process of assessment. This was followed by content analysis and data verification in the public domain where gaps or inconsistencies were found (Fig. 1).

Schematic for data collection and verification.

Data were collected from the Marine Stewardship Council website in early 2023 from (1) the lists of vessels that tuna clients had entered into the program, (2) client-reported tuna catches that are eligible for ecolabeling, and (3) client self-declarations about child and forced labor that were prepared within an MSC template. The template, it is important to make clear, contains a disclaimer3 that the client-supplied content “has not been audited or verified by any third-party entity” and “should not be construed to constitute certification of performance against a labor standard”; and yet, it is this information upon which the MSC has made various assurances about keeping forced labour out. The Marine Stewardship Council has stated that this information “indicates where MSC certified vessels are broadly in line with expectations from international, private, and NGO standards or guidelines on labor issues”27, for example.

This research is situated in the field of counter-accounting which involves content analysis and searching for incidents reported by independent and authoritative sources28 to learn whether the actions, processes, and impacts described in corporate disclosures on sustainability and human rights are supported by real-world evidence. It complements the body of research that has explored positive outcomes from MSC certification, like market access, changes in stock health, ecosystem impacts, and fisheries management29 and industry advocacy for harvest strategies30. Situated in the field of organizational management, counter-accounting explores a tendency in some corporate reporting on sustainability and human rights to communicate representations of reality that are clearly disconnected from the business activities and impacts31. For example, Le Manach et al. found that the promotional materials of the Marine Stewardship Council ecolabel feature photographs of small-scale fisheries although the catch it certifies is overwhelmingly from industrial fisheries32,33. Counter-accounting is a rising field within organizational science that addresses transparency in sustainability reporting in light of Baudrillard’s critical perspective of hyperrealism as a fixture of modern life, or a simulation of reality without origin that is difficult to distinguish from reality31.

This research was motivated by four factors. First, the MSC logo is found on tuna products in supermarkets worldwide from 21 of 23 global tuna stocks so it is consequential to perceptions about forced labor in tuna fishing. Second, hundreds of tuna fishing vessels and entities worldwide have been associated with forced labor recently by governments and authorities34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Third, in spite of long stints at sea and power imbalances, tuna fishers are reporting forced labor on tuna fishing vessels6 and some of those reports are highly accessible41,42,43. Fourth, certificate-holders and vessel owners alike gain logo rights and benefits from the MSC’s influence on market perceptions about how the product was made. Given its reach, the ecolabel could be a driving force for harm reduction. It could contribute to the prevention of forced labor in tuna fishing by aligning its market signals with its evidence and educating the fishing industry to recognize risks and adverse effects like debt bondage. Tuna data were collected from the Marine Stewardship Council website to see whether this is occurring.

Results

Primary data were collected into a database from the Marine Stewardship Council website (https://fisheries.msc.org, as of February 2, 2023), and depict that a live weight tuna catch of 2,561,055.4 metric tonnes (MT) is harvested from the sea each year and associated with the ecolabeling program by certifiers, according to the MSC website (see Supplementary Materials for the database and catch table). This catch, an equivalent to 53% of the estimated worldwide catch of 4.8 million MT44, is attributed to 3327 tuna vessels in the MSC program that are fishing on 21 of 23 tuna stocks, or 3098 distinct tuna vessel workplaces after removing 229 duplicated names of vessels supplying 2 or more certificates. This is a large catch for 3098 vessels in 49 fisheries. The vessels represent 10 percent of the 30,996 vessels currently registered with tuna regional fishery management organizations (RFMOs), and under half of the participants in the world’s largest tuna fishery in the Pacific Ocean7.

Who are the businesses benefitting from the MSC logo for tuna? From the data, the certificate-holding entities appear to be 32 distinct client groups comprised of 15 producer associations (2456 vessels), 13 tuna manufacturers (296 vessels), and 5 distributors (575 vessels) (Table 1) with each distributor holding multiple certificates (totaling 17). The fishers working on these vessels were not enumerated in the MSC program data. Their population was estimated to include 69,038 fishers based on the vessel gears and sizes described in the certification documents (see “Methods” section). Some vessel owners were identified (the fishing employers) on MSC’s website as were some applicable labor laws and authorities for fishing labour, but these were for a minority of tuna vessels in the MSC program (Table 2).

Seventy-four percent of the tuna in the MSC program was not linked anywhere in the data to vessel owner identities (fishing employers) which were missing for 1970 tuna vessels on the vessel lists, or 59% of the 3327 vessels listed over 49 tuna fisheries. Tuna vessel owners were identified for 1357 vessels representing 51% of the estimated population of fishers and 26% of the total tuna catch reported by certifiers See Supplementary Note 6. Of these, most vessel owner names (920) appeared on a single certificate (MSC-F-31498). Separately, on the self-declarations that clients are required to make in a MSC template, identities were missing for 2023 fishing employers and 61% of tuna vessels. Tuna vessel owners were identified in the data for 1304 vessels or 39% of tuna vessels in the MSC program and representing 54% of the fishers and 15% of the tuna catch. Some vessel owners were identified by the client only to clarify they are not the vessel owner and not engaged in labor issues on fishing vessels (for example, MSC-F-31371). Little can be known about working conditions on a fishing vessel where the fishing employers are participating anonymously.

Overall, twenty-two of forty-nine tuna certificates (45%) appeared to lack any form of information on vessel ownership (searched in vessel lists, certificates, public certification reports, surveillance reports, and client self-declarations). It cannot be said confidently that certified tuna products have transparent supply chains given that the MSC’s data demonstrates that most vessel owners are participating anonymously. Some information was available but it was discretionary and vastly incomplete, making it impossible in practice to assure that forced labor is kept out. The primary data on the MSC’s website does not answer the question of whether forced labor is kept out from tuna catches in the MSC program, nor answer any essential questions about fishing employment or whether the vessel owners might have forced labor convictions, See Supplementary Note 7. With a large majority of the identities missing for fishing companies, the data does not convince that client entities with forced labour convictions have self-disqualified, nor that fishers are less exposed to forced labour on the tuna vessels in the MSC program. The MSC’s primary data for tuna would not likely assist a government authority, fisher representative or union, or member of the public to locate and respond to tuna fishers in harm on the vessels in the program, for example who are experiencing strandings, untended injuries at sea, debt bondage or forced labor. In turn, the community is unable to notify or assist the MSC with detection or deterrence.

Unless the certificate-holding entity is also the vessel-owning entity, it is not likely to be named on convictions for the serious crimes that are excluded from the ecolabeling scope of the MSC Fisheries Standard. To identify more tuna fishing employers, the missing names for tuna vessel owners participating in the MSC names were filled in with a public search. This was necessary to learn how many of the clients holding tuna certificates are also vessel owners. The tuna vessels named in the MSC certification documents were searched on the vessel registries of government fisheries authorities, for example, a tuna vessel named on the vessel list for a fishery in the Western or Central Pacific Ocean was searched on the vessel registry of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, and a tuna vessel named in a Spanish fishery was searched on Spain’s registry. If not found there, the vessel name was searched on the four vessel registries of other tuna regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs). If not found there, the vessel name was searched on platforms Marine Traffic and Vessel Finder. This was deemed necessary because tuna vessels can move across oceans and the spelling of tuna vessel names can vary across platforms.

After this lengthy process, 1100 vessel-owning entities were identified. That brought the total number of vessel owner identities in the database to 2457 of 3327 tuna vessels (comprised of 3098 discrete vessels and 216 duplicates named on two or other tuna certificates). Ultimately, no vessel-owning entity could be identified for 869 tuna vessels that were listed on just five certificates (MSC-F-31527, MSC-F-31246, MSC-F-31486, MSC-F-31408) making it possible to see which of the MSC clients has opted not to identify the fishing employers. Of those vessels, 164 were not found on the vessel registry referenced in the certification documents, or on any RFMO registry, raising a question about the vessels’ standing to take tuna from the sea.

Very few of the organizations holding MSC tuna certificates are the owners of the vessels catching the tuna or the employers of the fishers working on the tuna vessels at 87 of 2444, or 4%. Very few certificate-holders are legally responsible for vessel conditions or employment practices as a result. This finding matters because ecolabeling is a promotional activity and the MSC has instituted procedures asking its non-fishing clients to submit self-declarations on child and forced labour that will not be assessed by certifiers5. Furthermore, the MSC has built a disclaimer into its self-declaration template. Using those provisions, tuna clients have returned content in the self-declarations that is of largely secondary or tertiary quality, and of very low confidence.

The content has significance for the welfare of tuna fishers nevertheless. The certificate-holders’ knowledge of fishing labor and their positions on forced labor are revealed in a closer look at the self-declaration content (see Table 2). Several self-declarations combined multiple fleets, flags, crew origins, and oceanic areas altogether as having identical labor conditions, even mixing purse seine and longline fisheries together (MSC-F-31475 and MSC-F-31441) despite having different trip lengths, crew origins, vessel owners and laws. Vessels from 17 flag states are represented altogether on one certificate (MSC-F-31362) for example. Although it is asked for, certificate-holders did not identify the applicable labor laws or the enforcement authorities for 1428 of 3098 tuna vessels (46%) and representing 50% of the MSC tuna (both are required). Of those who did, most said that the regional fisheries management organization is the labor authority when that is not the case.

Most of the content provided in the self-declarations for ecolabeled tuna described high-level corporate commitments to human rights. The content is overall quite generic and opaque. Some self-declarations contained identical phrasing. Very little content described vessel-level or even fleet-wide practices. One of the few vessel-level examples stated that labor recruitment costs are borne by the company (MSC-F-30011, MSC-F-31452) and this is salient information about preventing debt bondage. However, other certificate-holders said that some costs are borne by fishers and that vessel owners are deducting tuna fishers’ wages for transit costs to and from the workplace, for crewman’s gear, and food costs (MSC-F-31371, MSC-F-31407) or if they had to leave the fishing vessel for any reason (MSC-F-31440). This information is also salient about debt bondage but describes conditions that the ILO has said are indicative of it45, for example where fishing crew members must pay the costs of leaving the vessel workplace due to a serious work injury, violence, or non-payment of wages.

Rather than illustrate fault, the data found in MSC’s client self-declarations for ecolabeled tuna demonstrates that forced labor and its risks in tuna fishing on the High Seas are not well-understood by the tuna industry, or likely by the MSC certifiers collecting the information, or the Marine Stewardship Council. Asked how fishers can report abuse, one certificate-holder said that “local people’s governments are responsible” (MSC-F-31399) where it is a flag state responsibility, others that “[fishery] observers report any crew grievances made to them” (MSC-F-31362, MSC-F-31553) when this is not a mandate of fisheries observers. Asked about the legal age of work for tuna fishing on the High Seas, it is concerning that most responses were age sixteen (“the younger, the better” in the self-declaration for MSC-F-31497). Child hazardous work laws prohibit the recruitment of anyone younger than eighteen years old to industrial fishing in numerous countries, for example in Indonesia where the certificate-holder mis-stated the legal age of fishing work as 15 (MSC-F-31471) and appeared to condone illegal employment when it said, “if children aged between 15–18 years are involved in the scope of certification, then the provisions in the Fair Trade standard (FHR-PC 1) applies”.

One tuna client’s self-declaration stood out from the others (MSC-F-31349) for inaccuracy and inconsistency with the lived experiences of fishers who reported forced labor on three vessels listed to the single certificate. The vessels were named in a high-profile report made in 2019 by the Serikat Buruh Migran Indonesia (SBMI, in English the Indonesian Migrant Worker Union) and Greenpeace46. Tuna from one of the vessels, the Hangton 112, was then banned in 2021 by the USA due to debt bondage and forced labor47. The ban and investigation remain active48 and the employer responsible is still named on the certificate, although that vessel was removed. The threshold for a trade ban is sufficiently high to say with confidence that the company has benefitted from forced labor and the MSC could have disqualified the company, according to 3.1.1 of its Labour Eligibility Requirements. It is fair to ask who is eligible for disqualification from the ecolabel if not a fishing company under a ban by a government for forced labor on its vessels? In this case, tuna fishers reported that the ecolabeled tuna was made with forced labor on the banned vessel and two other vessels operated by two companies on the certificate. The companies did not self-disqualify and the self-declaration states that “there is no evidence of any debt bondage”49.

Is tuna ecolabeling causing fishers more harm than good? For 53% of tuna fishers (37,061), certificate-holders have dismissed even the potential for labor violations onboard without providing any details of proof or prevention. Eighteen certificate-holders refuted that tuna fishers working on the listed vessels could be exposed to debt bondage on the vessels at all, with responses that included “No child or forced labor can exist”, “Debt bondage N/A”, “there are no issues with debt bondage”, “it simply does not exist” or equivalent (MSC-F-31349, 31558, 31537, 31530, 31556, 31157, 31452, 31408, 31555, 31341, 31498, 31245, 30029, 31553, 31554, 30002, 31371, 31407). These representations contrast with fisher reports of forced labor in the public domain, See Supplementary Note 8 (Table 3).

Tuna vessels implicated in forced labour by fishers recently, this research shows, are ecolabeling participants. Eleven vessels currently involved in a forced labour investigation were added to a tuna certificate in June 2024, details of which are public50,51. The fishing entities have not been convicted, it is important to make clear, but the addition of their vessels reveals that the ecolabeling procedures admit fish under investigation for forced labour into the certified supply chain, rather than keeping it out. The contrast between the assurances that MSC has made about fishing labour conditions and the actions by a majority of its tuna clients, using its procedures, raises a new question about fisher welfare on vessels fishing for ecolabeled tuna. The Marine Stewardship Council has considered the exposure of tuna buyers to forced labour risk, but has it considered the exposure of fishers, and what the implications of its procedures may be for fishers who are experiencing forced labor today?

Discussion

The Marine Stewardship Council has made assurances about keeping forced labour out from the certified tuna supply chain which appear to be unsupported by the primary data on its website (https://fisheries.msc.org) for tuna. When making the assurances in 2022, tuna fishers in the Pacific Ocean were unable to leave certified vessels due to pandemic restrictions, many having been at sea already several years. Furthermore the MSC had issued derogations waiving labour and other mandatory certification requirements (like site visits) that were in effect and extended through September 2023 (10 derogations). Additionally for tuna, the MSC had waived all client conditions in a variation it called ‘MEGVAR’. Accurate and timely data were not being collected by certifiers about tuna, tuna vessels, tuna employers or tuna fishers when the MSC announced its labour eligibility requirements and policy “aimed at providing transparency and enhancing assurance of the absence of egregious labour practices from fisheries and supply chains that are under assessment or certified to the MSC standards”5. These announcements were disconnected from MSC’s empirical data for tuna and from a reality of forced labour that fishers had reported on some vessels in the program.

The primary data found on the Marine Stewardship Council website reveals that ecolabeling clients have used the labour procedures to make opaque and aspirational statements that are less in step with the notions of human rights due diligence and harm reduction for tuna fishers and more in step with dissociating certified products from liability risks and the forced labour controversy. The procedures do not contain safeguards, and this is evidenced by the large volume of clients who used them to refute forced labour generally. By then repeating its clients’ unaudited refutations, the MSC has acted as a second party to a denial of modern slavery that rejects the lived experience of fishers and stakes a position on human rights in the tuna sector that could be harmful to fishers in the present and future.

The major findings from this research into ecolabeled tuna are the following. First, with seventy-four percent of ecolabeled tuna coming from vessels with no listed employer, it follows that the vessel employment practices and violations for which these employers are responsible are unknown. Second, data from tuna vessel lists and tuna client self-declarations did not “offer an overview of labour risk management practices at the vessel level” for ecolabeled tuna, or “illustrate practical approaches in place across MSC certified fisheries to prevent child and forced labour” for ecolabeled tuna27. Third, certificate-holders hold the control of what is said about forced labour on the MSC website because certifiers do not assess or verify the information. Tuna clients provided positive, often risk-free accounts of tuna fishing and provided very little primary information that sounded promotional–therefore not to be repeated in assurances by the MSC and merely disclaimed in the fine print. Fourth, a search limited to high-profile reports in the English language found that fishers have reported forced labour on multiple vessels in the program since 2019. This information was not hard to find and suggests that the Marine Stewardship Council lacks a channel into its data which would allow it to detect labour violations on vessels in its program.

The Marine Stewardship Council has implemented procedures that are especially problematic because a majority of its tuna clients used them to refute the reality of debt bondage or forced labour while fishing on the High Seas, when authorities like the ILO have said clearly that they are. As fishing labor controversies have grown exponentially in number52, authorities like the International Labour Organization (ILO) have drafted clear global standards for good jobs on fishing vessels that include ILO Convention 188 on Work in Fishing and the ILO guidelines to promote decent work in fishing. A unanimous 2011 decision by the UN Human Rights Council defined the business duty as “to address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved, for their prevention, mitigation and, where appropriate, remediation” and set out this duty in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) See Supplementary Note 98. These protocols are not referenced in the MSC Fisheries Standard, MSC Labour Eligibility Requirements (2022), or MSC’s template for self-declaration about child and forced labor. They are not referenced in the Fisheries General Certification Requirements (v2.6, 2023) and Fisheries Certification Process (v3.0, 2022) where “safeguarding jobs” is first among the sustainable fishing attributes in the introductions to these core program documents. The MSC is not educating its certificate-holders about ILO’s fundamentals for fishing labour, or how to collect the information on adverse human rights impacts needed to comply with the UNGP protocol for human rights due diligence53,54 which involves accepting that forced labor occurs.

The word client appears 430 times in the ecolabel’s process documents, and the word fisher appears 44 times, See Supplementary Note 109). Client entities convicted of crimes could self-disqualify, in theory, but signs of enforcement were absent and instances of avoiding to self-disqualify were present in the program’s data. Ocean transparency is not much increased from the information that certifiers have collected from tuna clients and lumping multiple oceanic areas, fishing fleets and Flag States. Some self-declarations on child and forced labour lumped together multiple certificates. Viewed together, MSC’s labour procedures, and the data it is collecting, suggest that the ecolabeling approach to handling labour and human rights is client-centered and not fisher-centered. Clients are not asked to prove compliance first. Certifiers are not instructed to test their client’s compliance with explicit auditable criteria, nor to trace the candidate tuna to the fishing companies (and lately avoidable, See Supplementary Note 11).

These findings fit into a larger picture of the use and design of voluntary corporate measures to neutralize human rights and sustainability concerns. Opaque reporting on sustainability and human rights is common because it serves to disconnect a business from corporate problems and violations that are widely reported by external sources55. Disconnection can be achieved with various reporting strategies for neutralizing the controversy, for example with reporting language that highlights the merits of good practices generally but not the company’s actions specifically, which has the effect on the perception of decoupling the business from adverse environmental or human rights impacts56 although the workers and conditions remain unseen and unknown. Furthermore, certification is a neutralization strategy that businesses choose for externalizing a sustainability problem particularly, scholars have shown, in low price-sensitive markets with a fairly large informed-consumers market and a low ratio of certification cost to production cost57. This is achieved is by certification’s pooling equilibrium. All participating firms choose the same claim and their results are pooled, which creates the power to change market perceptions without necessarily increasing the transparency of specific operations or revealing the different strategies of the firms58. One firm could take substantial action and another only a symbolical adoption intended to do only the bare minimum for the same result59. Loopholes like derogations, variations, and unit-lumping can be used to avoid disclosure about sensitive matters, like poor practices and criminal associations.

When consumers buy ecolabeled tuna, it is reasonable for them to perceive that the logo signifies that the product was made without crime and human rights abuse, especially where those assurances were made. The same is true for a supermarket buyer or a government perceiving that the tuna goods need no further human rights due diligence. A judge considering the case of tuna fishers coming forward to press charges over forced labour on a certified vessel, would also consider ecolabeling assurances if the fishing employer shows an MSC certificate, a link to their self-declaration on the MSC website, and the ecolabel’s disqualification procedures in their defense. Consumers, government officials, and judiciary are unlikely to drill into an ecolabeling program’s derogations and disclaimers to check whether the company is participating symbolically.

To avoid causing harm to tuna fishers, the Marine Stewardship Council should correct four omissions in its program. The first omission is the lack of a firm rule that vessel owners must be identified. Approximately half of the fishing jobs could not be traced in the MSC tuna data because certificate holders were not required to identify the fishing employers. This is a very powerful omission because certificates could include vessels that are owned by unnamed entities associated with serious crimes like forced labor, illegal fishing, bribery, money laundering, drug smuggling, or other transnational crimes and sanctions, and introduce liabilities they are not aware of.

The second is the omission of requiring certifiers to screen vessels and vessel-owning entities against highly publicized lists of implicated vessels, such as the Notice of Sanctions Actions published on the Federal Register of the United States identifying individuals and entities sanctioned for serious human rights abuse in their fishing operations35. Due to this omission, vessels implicated on such lists could join the program undetected. A certificate-holding entity could be unaware of violations perpetrated by vessels it does not own. It could be exposed to or complicit with the sale of fish produced from crime, and so could its tuna buyers and consumers.

The third omission is the lack of clarity provided by the MSC about the fishing labor information it collects. The MSC has made assurances knowing that the supporting information is not confident, because that is the design of its procedures. In its own analysis, only 32% of its client self-declarations were submitted directly by the vessel owners27 program-wide and that number is far fewer for tuna, about 4%, See Supplementary Note 12. This omission matters to the way that the ecolabel generally describes its data as audited and itself as neutral10. The labour assurances were not distinguished as second party and promotional information and as a result the market could misperceive that the MSC has collected workplace information directly from fishing employers and verified it. In reality, most of it was self-reported by trade associations, manufacturers, and distributors that could not reasonably be expected to provide a vessel-level view of proprietary employment practices and conditions because they are not the employer. This omission, and misperceptions that could flow from it, could potentially deflect attention and detection away from the reality where fishers are experiencing forced labor or egregious abuse.

In conclusion, the Marine Stewardship Council logo, which is prominent internationally and in nearly every supermarket in the UK, does not set a legitimate standard of care for keeping forced labor out from the certified tuna supply chain. It has set out perceptions in the market with significant consequences for fishers, See Supplementary Note 13. These findings are significant because the ecolabel recently announced that 59% of the global wild tuna catch comes from MSC-engaged fisheries, or 2,969,000 metric tonnes60. Most tuna on Planet Earth could be associated with the broadly positive statements the Marine Stewardship Council has made about conditions on vessels fishing for tuna on the High Seas, much caught anonymously. This research highlights a lack of genuine traceability for tuna certified through the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) label. Policy-makers should regard ecolabeling assurances with caution where the businesses making the product are not identified.

The Marine Stewardship Council has established ownership of the sustainability agenda for the seafood sector since the 1990s. As an ecolabel, it has successfully expanded its reach across fisheries and markets without expanding the scope of responsibility for its Fisheries Standard much beyond the management of fish stocks by governments—even as norms shifted well beyond a single species-based definition of sustainability to include ecosystem-based and multi-species fisheries, climate and social priorities. Future research might look further into neutrality and the second party roles that ecolabels play as elements of their success. This includes the language that ecolabels use when making statements beyond the scope of their standards—particularly where the supporting data consists entirely of client self-reports (unaudited, unverified, self-interested). Future researchers and governments should consider that in reality tuna fishing is among the world’s most dangerous and isolated jobs. Corporate disclosures should be read analytically to distinguish actions and words where they contain broad statements about human rights without details about the rights-holding people involved. Scholars might also use the vessel database generated for this research to pursue new knowledge about fisheries transparency and beneficial ownership in the tuna fisheries sector.

Methods

A database was built from primary data that were present on the website of the Marine Stewardship Council (https://fisheries.msc.org), as of February 2, 2023, and it is provided in Supplemental Materials. The database elements and relationships are summarized in Table 4. They derive from the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011) and the OECD Due Diligence Guidelines for Responsible Business (2018). Vessel lists and self-declarations about fishing labor by certificate-holders were downloaded in late January 2023 and are available upon request. Tuna catches were collected from the figures provided on the MSC tuna client fishery pages. Website content changes over time so these data were confirmed a second time in December 2023 with a web archives reader.

Content analysis involved counting the presence, partial presence, or absence of information for every vessel associated with an MSC tuna certificate. This was strictly quantitative in nature and the information counted was not judged quantitatively, apart from noting data absences. For each vessel, data were collected for (1) the identity of the vessel, including the vessel-owning entity that is also the fishing employer, (2) the labor laws applicable to the fishing vessels, and the enforcement authorities, and (3) any example of a practice on a vessel for protecting fishers from forced labor or debt bondage. These data were searched in several documents posted on tuna client fishery pages, including the vessel lists, certification documents, and client self-declarations (per 7.4.2.7-8 in the Marine Stewardship Council Fisheries Certification Process v2.2 2020).

Fishers were also enumerated from the tuna data by assigning a fishing job value to all certified vessels according to the fishing gear and size described in the certification documents. These values were 15 crew members for a distant water longline vessel, 5 crew per small longline vessel, 28 crew per purse seine vessel, 30 crew per pole and line vessel, 20 crew per handline vessel, and 3 crew per troll vessel. The values were generalized through research in the literature on tuna vessels published by the Secretariat for the Pacific Community and they were cross-checked with a tuna monitoring-control-surveillance specialist.

When the database revealed that most tuna fishing employers were unidentified, a decision was taken to search and fill the names of vessel owners and operators from government vessel registries, which included the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC), International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), and the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC). This online name search, as well as the search for fisher reports of forced labor, was kept intentionally simple to demonstrate that it could be done without requiring special skills or training. The names of certificate-holding entities were also searched and categorized according to their different functions and positions in the tuna supply chain as tuna fishing entities, tuna manufacturers, and tuna distributors.

When the database revealed that the potential for exposure to debt bondage or forced labor while fishing for tuna on the High Seas had been dismissed for over half of the tuna fishers working on vessels in the program, then a decision was taken to perform a limited search in the public domain for incidents reported by independent and authoritative sources. The decision was taken because forced labor was dismissed in eighteen client self-declarations and the volume of ecolabeled tuna represented was significant. The search was limited to high-profile and English language reports and employed as a reliable method of counter-accounting the information published in corporate disclosures and sustainability programs31.

The initial intention of this research, as mentioned, had been to replicate the MSC-sponsored analysis by Tindall et al.27 for tuna, and using the data categories they described. However, the tuna data collected from the MSC website (as of February 2, 2023) were substantially different in character, making those methods a poor fit. Only about 4% of tuna clients were vessel-owning entities, for example, in contrast to 32% in that review. Furthermore, that analysis appeared to classify high-level corporate commitments as vessel-level labor protections and this was deemed inappropriate for the current research. The MSC-sponsored analysis had also concluded that legal compliance was demonstrated even if “the flag state for all vessels was not always stated”11. This notion was rejected from the current research because the basic units and laws of fishing work are defined by the flag state, and the MSC’s template requires its clients to identify both. Splitting the notion of legal compliance away from flag state requirements risks recasting compliance as an aspirational privilege that non-employers could satisfy voluntarily and at their discretion, for example by signing onto a pledge or joining a roundtable. That would not satisfy the business duty that is defined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and could inadvertently dissociate the vessel-owning entity from harm and crimes that are being experienced by people.

Responses