Male sex accelerates cognitive decline in GBA1 Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by a heterogeneous range of motor and non-motor symptoms1. Among these, the occurrence of cognitive impairment is one of the main causes of a poorer quality of life2. The different clinical trajectories observed in PD pose considerable challenges in identifying appropriate participants for clinical trials. As a result, there is a pressing need for a more accurate identification of factors that may increase the risk of PD subjects to develop cognitive impairment.

Genetic factors are known to contribute to the susceptibility to cognitive decline and dementia in PD3. Heterozygous variants in the glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA1), occurring in about 8–12% of PD subjects worldwide, seem to accelerate the neurodegenerative process already in the earlier stages of the disease4, leading to a significant dopaminergic damage and a more severe clinical phenotype5. Indeed, GBA-PD subjects generally have an earlier disease onset, a higher prevalence of non-motor symptoms and a greater risk of progression to dementia compared to non-mutated subjects6.

Sex is another established factor that affects incidence, natural history, and clinical manifestations of PD. A recent meta-analysis confirmed the clear male preponderance over females (59% vs 41%)7, with men manifesting more severe motor symptoms and faster disease progression than women8. From a pathogenetic perspective, genetic, hormonal, neuroendocrinal and molecular players all contribute towards these sex-related differences9. In particular, steroid sex hormones, and especially oestrogens, seem to play a crucial neuroprotective role and anti-inflammatory function against PD pathology4.

GBA1 pathogenic variants are equally detected in PD subjects of both sexes4, surpassing the potential impact of environmental exposures and hormonal influences that likely result in the higher male prevalence characterising idiopathic PD. Thus, it becomes critical to investigate the potential interactions between GBA1 genotype and sex, and their combined influence on development of cognitive impairment.

In this study, we embarked on a comprehensive exploration of the mutual role of sex and GBA1 mutations in modulating dopaminergic vulnerability as well as the risk to develop dementia in PD subjects. By shedding light on these multifaceted dimensions, we aim to deepen our understanding of PD cognitive manifestations and pave the way for more targeted and effective interventions.

Results

Baseline features

The demographic and clinical characteristics of GBA-PD (M/F: 66/62) and nonGBA-PD (M/F: 269/163) groups are shown in Table 1. Upon GBA1 variant classification, 25% subjects carried “risk” variants, 56.2% “mild”, 10.9% “severe”, and 6.2% “unknown”. The N409S “mild” variant emerged as predominant, being detected in 50% of mutated individuals (Supplementary Table 1).

At baseline, the two groups were comparable for age and educational level, but GBA-PD showed an earlier age at symptoms onset (AAO), longer disease duration, a significantly more severe motor profile and higher RBDSQ than nonGBA-PD. On the cognitive side, MoCA scores were comparable between GBA-PD and nonGBA-PD, although GBA-PD showed lower performance on visuospatial function.

When assessing sex-related differences, regardless of GBA1 carrier status, PD males showed more severe RBD and motor symptoms, while females showed greater autonomic dysfunction. PD males also showed lower memory performance than females, while the opposite was observed for visuospatial scores. No differences emerged in global MoCA scores at baseline between sexes (Table 1).

When combining sex and GBA1 genotypes, GBA-PD males had significantly more severe REM sleep disturbances than all other groups, and the worst motor scores, albeit significant only vs. nonGBA-PD, regardless of sex. Other inter-group comparisons at baseline confirmed the former observations of worse autonomic dysfunction, worse visuospatial performance and better memory performance in all PD females compared to nonGBA-PD males (Table 2).

No differential distribution of concomitant medications used to treat psychiatric conditions, cognitive dysfunction, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and cardiovascular events was observed across the four subgroups (Supplementary Table 3).

There was no difference in sex-specific distribution of GBA1 carriers (59 men, 50%). Regarding variant subgroups, we observed a higher prevalence of males for the “severe” variants (9 males, 64.3%), while no sex differences were observed for other variant classes (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, selected variants prevailed in either sex (e.g. T369M in males and E326K in females). The different subgroups defined by the genetic variants were similar in terms of MoCA scores at baseline. However, when exploring the interaction between sex and GBA1 variants, we found that GBA-PD females carrying “mild” variants outperformed GBA-PD males with “risk” variants in HVLT memory tasks (delayed recall and recognition) (Supplementary Table 2).

Dopamine Transporter Imaging at baseline

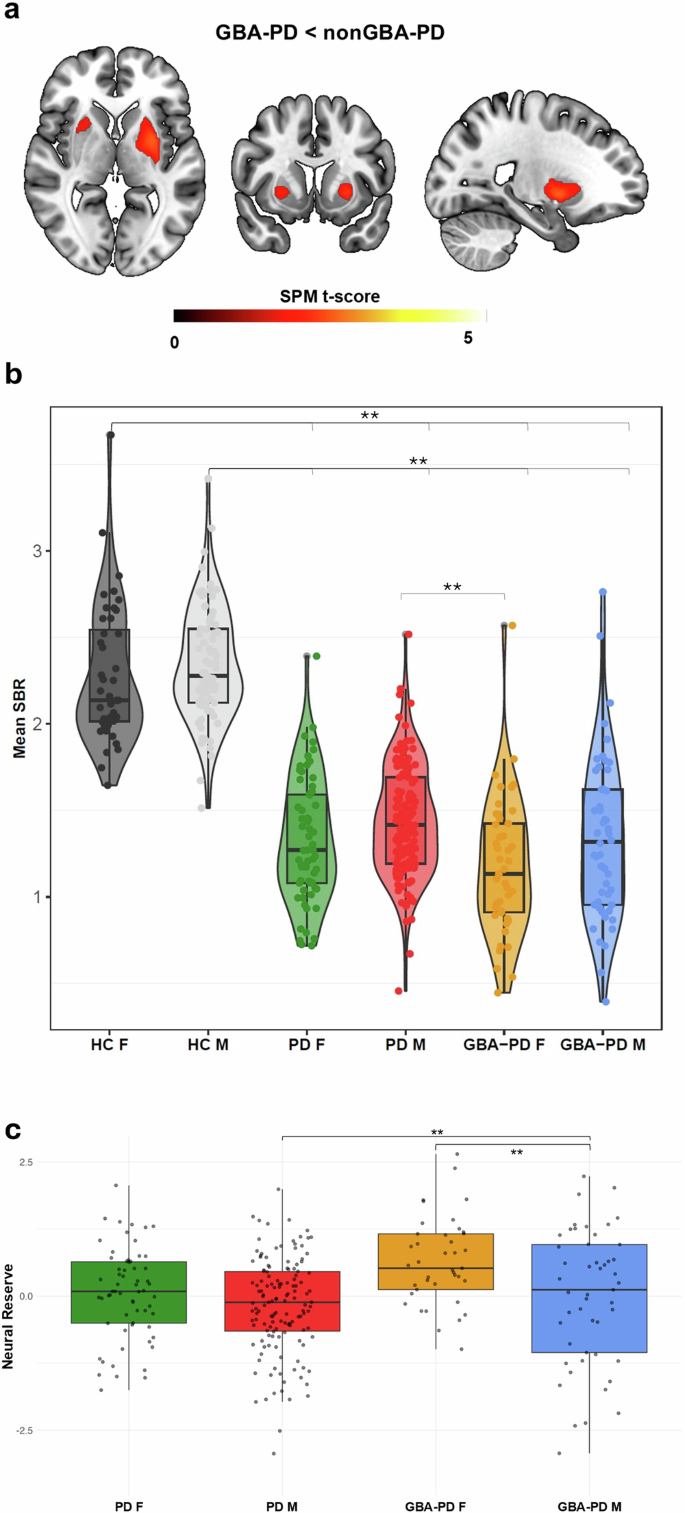

GBA-PD showed reduced dopamine uptake in putamen [MNI XYZ Coordinates: −28; 0; −2/30; 8; −4] compared to nonGBA-PD (Fig. 1a).

a Significantly reduced dopamine binding in GBA-PD subjects compared to nonGBA-PD subjects, resulting from the voxel-wise regression model, adjusted for age at acquisition, Asymmetry Index, MDS-UPDRS-III and LEDD. b Violin plots representing the distribution of dopaminergic binding potentials among the four clinical and HC groups. c Box plots representing the distribution of neural reserve score among the four PD groups.

Of note, we found significant reduction between GBA-PD females and nonGBA-PD females at voxel level [MNI XYZ Coordinates: 22; 0; −4/−24; 0; −4]. No differences were observed between males in the GBA-PD and nonGBA-PD groups.

Off-line statistical comparison showed that, despite a milder motor clinical profile (Supplementary Table 4), GBA-PD females showed the greatest dopaminergic impairment, which was significantly worse than nonGBA-PD males (Fig. 1b), with a trend toward significant (p = 0.176) reduction characterizing GBA-PD females carrying “mild” variants (Supplementary Fig. 1). Of note, GBA-PD females showed higher W scores, suggesting greater neural reserve, compared to their male counterparts (Supplementary Table 4).

Cognitive trajectories at follow-up

During the follow-up period (mean ± SD: 6.87 ± 3.2 years), 228 out of 560 PD patients (40.7%) experienced cognitive impairment, with MoCA scores ≤ 26 at follow-up assessment; this subgroup included 146 males (out of 335 = 43.6%), 66 GBA1 carriers (out of 128 = 51.6%) and 206 LO-PD (out of 560 = 36.8%) patients. By analysing the percentage within each group, we observed that cognitive impairment occurred in 57.1% of cases with “severe” variants and in 54.3% of cases among the “mild” variants. Among the GBA1 carriers of “mild” variants, 64 (88.8%) had the N409S variant, and of them 33 (51.6%) developed cognitive impairment. Conversely, we found a lower prevalence of cognitive impairment in individuals carrying “risk” variants (40.6%) and those with “unknown” variants (25%) (Supplementary Table 1).

We found that the levels of MoCA deflection were significantly higher in GBA-PD compared to nonGBA-PD (Table 1).

GBA-PD males showed a significantly steeper MoCA deflection and memory impairment not only when compared to nonGBA-PD males and females, but also when compared to GBA-PD females (Table 2). GBA-PD females carrying “mild” variants showed better performance than “risk” and “mild” GBA-PD males in HVLT immediate recall (Supplementary Table 2).

The linear mixed-effect modelling showed that sex and AAO were associated with significant rate of changes in MoCA scores across time. Notably, male PD patients had significantly faster declines in global cognition compared to female PD patients; and late-onset PD (LO-PD) compared to early-onset PD (EO-PD) patients. A significant interaction was observed between AAO and sex, with LO-PD males showing significantly higher declines in global cognition than EO-PD females. No significant difference was observed among GBA-PD and nonGBA-PD. However, a significant interaction between sex and GBA1 positivity was found in the change of MoCA scores over time, where GBA-PD males showed significantly higher rate of change in global cognition than GBA-PD females and nonGBA-PD females. We observed a significant interaction in the decline of MoCA scores, due to a higher rate of decline in LO-GBA-PD group compared to EO-GBA-PD and EO-nonGBA-PD (Table 3). All the above results were replicated in the subcohort of PD patients without LRRK2 mutations.

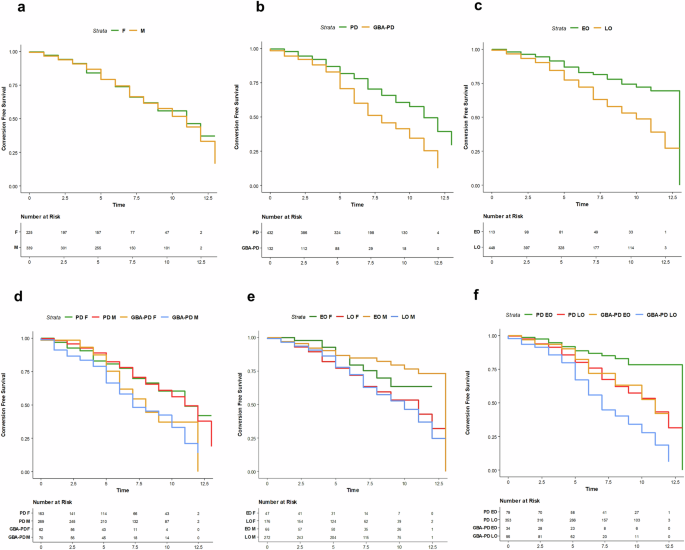

The Cox regression model showed that GBA1 positivity produced a significant risk of cognitive impairment over time (Fig. 2b), also when the model was adjusted for sex. Both “severe” and “mild” GBA1 variants were significantly associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment. Of note, “risk” variants showed an HR below 1 indicative of a protective effect than the other variants (Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the association between the probability of conversion to cognitive impairment, adjusted for age, disease duration, and education at baseline. The effects estimated include: (a) biological sex; (b) GBA1 carrier status; (c) age at symptoms onset (AAO); (d) interaction between GBA1 genotype and biological sex; (e) interaction between biological sex and AAO; and (f) interaction between GBA1 carrier status and AAO.

When we considered AAO, participants with LO-PD showed a significantly increased risk of cognitive impairment during follow-up time (Fig. 2c).

We found an interaction between male sex and GBA1 positivity on the risk of cognitive impairment (Fig. 2d). GBA-PD male carriers of “severe” and “mild” variants showed a significantly higher risk of cognitive impairment than “unknown” and “risk” variants (Supplementary Fig. 2).

LO-PD males showed a significantly higher risk of cognitive impairment, and the interaction effect between AAO and GBA1 positivity showed a higher risk of cognitive impairment in GBA-LO-PD. See Table 4 and Fig. 2e, f.

Consistent results were found in the sensitivity analysis performed on 440 subjects, all with 3-year follow-up available, and with a clinical profile similar to the general population (Supplementary Table 5–7). The risks associated with sex, GBA1 positivity, and AAO, as well as their interactions, mirrored those observed in the Cox model for the broader population (Supplemental Table 8). This consistency indicates that the associations we reported are unlikely to be significantly affected by data censoring or the presence of LRRK2 mutations.

Discussion

The interaction between sex and genetics is complex and poorly understood in the context of PD8. Sex-related frequency differences have been reported in genetic forms of PD, with observed variation depending on the specific gene10. As regards GBA1, the sex distribution remains controversial11,12,13, with discrepancies depending on the GBA1 variants under investigation4,10. For instance, a previous report indicated a preponderance of women among carriers of “severe” variants, while men were more likely to harbour “mild” and “risk” variants10. Here, in a large cohort of PD subjects extracted from the PPMI dataset, we failed to detect relevant differences in the prevalence of GBA1 heterozygous carriers between men and women.

The main aim of this study was to investigate the combined role of sex and GBA1 carrier status in the risk of progression toward a cognitive impairment, to address the key question whether GBA1 mutations and sex have an independent or cumulative effect on cognitive outcomes.

Indeed, our results highlighted that the combination of GBA1 mutations and male sex is associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment and a steeper MoCA change along the disease course. This novel finding is in keeping with previous research reporting male sex as a predictor of higher risk of developing cognitive decline14 or even dementia15, as well as with the known association of GBA1 variants with cognitive impairment5,16,17,18. Here, we found significantly higher HR of cognitive decline at follow-up consistent with previous reports (see refs. 17,18) and a more pronounced MoCA score deflection.

To the best of our knowledge, only one previous study, conducted in a large cohort of 4923 individuals with primary degenerative parkinsonism, has reported similar findings4. That study demonstrated an interaction between GBA1 variants and male sex, which was associated with a higher prevalence of Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies compared to idiopathic PD4.

On the other hand, female biological sex seems to exert a protective effect also on GBA-PD condition. Indeed, we found no association between female sex and risk of cognitive decline in GBA-PD subjects, also supported by a slower cognitive decline in GBA-PD females than males. Taken together, these findings suggest the existence of relevant sex-related discrepancies in the manifestation of cognitive dysfunction in GBA-PD. Interestingly, despite a more benign clinical phenotype, GBA-PD females showed greater dopaminergic deficits as compared to GBA-PD males.

Notably, we applied an already validated method19 to obtain standardized individual differences between predicted and observed dopaminergic deficit (i.e. W scores) as an operational measure of neural reserve. We found that in GBA-PD females showed greater W scores than males, suggesting that more dopaminergic dysfunction is tolerated at a milder level of motor deficit in the former group. In the course of the disease, GBA-PD females can counteract pathological brain changes through mechanisms of neural reserve and neural compensation20. In the general population, women tend to exhibit higher physiological levels of dopamine in the striatum, reflecting differences in basal dopamine system organization and/or neuroanatomy21. The dopamine system contains a high density of oestrogen receptors, through which hormones exert their protective role on dopaminergic functions21. Such protective effects of oestrogens are achieved by reducing oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, limiting neuroinflammation, and preventing the deposition of α-synuclein and neural injury22. Intriguingly, experimental studies showed that the decline in oestrogen levels during menopause may disrupt oestrogen receptor-mediated signalling in key brain regions, potentially impairing neuroprotection in females23. Another aspect under investigation is related to the detrimental role of GBA1 mutations on sphingolipid homeostasis. Abnormal sphingolipid accumulations have been observed in GBA-PD patients in both post-mortem brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid24. GCase catalyzes the hydrolysis of glucosylceramide (GlcCer), a sphingolipid. These lipids are essential for maintaining membrane functionality, facilitating intercellular communication across different tissues, including the brain, and regulating programmed cell death25. Of note, sphingolipids influence the secretion of steroid hormones at multiple stages, which in turn affect the metabolism of sphingolipids themselves26.

Thus, both environmental and hormonal factors may counteract PD-related pathology over the lifetime of pre-menopausal women, contributing to build a neural reserve through relevant neurobiological effects, even in GBA1 carriers27. Overall, it is tempting to speculate that a more advanced stage of neurodegeneration is needed in females to reach the same clinical severity observed in GBA-PD males.

Future prospective studies – focusing on the influence of hormones on GBA1-related pathology – could lead to a better understanding of the wide motor and cognitive between-sex variability in PD, as well as reveal new therapeutic avenues or preventive strategies.

Besides cognitive impairment, GBA-PD males showed higher occurrences of RBD disorders compared to all other groups. This finding is of particular interest as it is in line with the male predominance of RBD28, but also with the strong association between the presence of RBD and GBA1 carrier status5,29. RBD in PD subjects is considered a marker of a more malignant phenotype, with more rapid progression of motor and non-motor symptoms30, as well as being related to more severe spreading of α-synuclein pathology at post-mortem assessment31.

From a neuropsychological perspective, we observed that males tend to perform worse than females in memory tasks, consistent with numerous studies highlighting greater memory-related deficits in male than female patients with PD14,32,33. On the contrary, females show lower performance in visuospatial abilities. This finding aligns with previous PD studies8,14,33,34 and may also reflect the higher visuospatial performance commonly reported in males within the general population35,36.

When considering the interaction between sex and GBA mutation or variant carrier status, these differences remain unchanged. This suggests that the observed disparities are primarily driven by gender and remain unaffected by GBA1 carrier status.

Of note, we found that older age at onset was, independently and in combination with both GBA1 mutations and male sex, associated with future development of cognitive impairment.

An older age at the onset of the disease has already been associated with increased risk of incident dementia in PD, due to a combined effect of the disease and aging process, possibly acting on nondopaminergic brainstem structures (i.e. cholinergic and noradrenergic systems)37. Here, we found that AAO, together with male sex, modulates the detrimental effect of GBA1 mutation on PD cognitive decline.

Another aspect emerging from our analysis is related to the differential effects of GBA1 classes of variants on cognitive decline. Previous evidence showed conflicting results on the relationship between classes of GBA1 mutations and PD phenotype as well as the risk for dementia4,18,38,39. Indeed, Cilia et al.38 found that carriers of “severe” variants had greater risk for dementia compared to carrier of “mild” variants, even if the latter showed a 2-fold higher risk of dementia than nonGBA-PD subjects38. Our former study on a large Italian cohort also showed that GBA-PD patients with “severe” variants exhibited greater risk of non-motor symptoms (e.g. cognitive impairment) compared to GBA-PD carrier of “mild” variants40. Later on, Lunde et al. 18 reported that “severe” variants are associated with a faster progression to dementia than carriers of “risk” variants (e.g. E326K)18, a finding not confirmed by Straniero et al.4, who found a higher risk of dementia not only in association with “severe” variants, but also with the E326K “risk” variant4.

The present study on the PPMI cohort confirms that GBA1 “severe” variants are generally correlated with a more severe clinical phenotype, but it shows that “mild” variants also increase the risk of cognitive decline in PD. Conversely, a much lower proportion of “risk” variant carriers eventually converted to dementia at follow-up, suggesting that this category is characterized by a more benign outcome, especially on the cognitive side. The higher risk of conversion found in carriers of both “mild” and “severe” mutations may partially explain the considerable clinical variability reported among GBA-PD subjects in terms of cognitive dysfunction and motor disability38. However, we found that 46% of “mild” and 43% of “severe” variant carriers showed stable cognitive profiles at follow-up, suggesting that other risk factors, in combination with genetic risk factors, should be considered to shed light on PD heterogeneity. Overall, this still controversial evidence suggests that the current classification of GBA1 variants, which is based on their role in Gaucher’s disease, may not adequately reflect their pathogenic role in PD, and new classification approaches should be investigated. Given these premises, future studies further addressing the issue of heterogeneity within the spectrum of GBA1 genotypes and its relationship with sex should be implemented, also considering the effect on PD motor and non-motor phenotype and clinical trajectories. Moreover, our data should be confirmed in large population-based studies to limit bias in the ascertainment.

It should be acknowledged that in the survival analysis, cognitive impairment did not occur in 50% (effective 40.7%) of the sample, which restrict the interpretation and generalizability of the results. In addition, when analyzing the MoCA trajectories using LME, no statistically significant difference in the rate of cognitive decline was observed between GBA-PD and nonGBA-PD groups. The discrepancy may arise from differences in the two statistical models (LME vs Cox regression); indeed, LME accounts for repeated measures over time, which could lead to a more conservative estimate of cognitive decline rates.

In conclusion, we confirm that GBA1 variants are the major risk factor associated with cognitive impairment, however, this effect is particularly evident in association with the male sex. Indeed, we found that, among GBA1 carriers (mainly of “severe” and “mild” variants), PD males showed the greatest risk of develop cognitive impairment over time. These elements should be considered when interpreting the current literature and planning future studies. Understanding the role of genetic variants on the course of cognitive decline over PD progression will foster a more accurate disease prognosis and may help to a better future clinical trials design and patients’ selection. In particular, the effect of sex on GBA1 mutation should be considered in the emerging therapeutic strategies targeting GBA1-regulated pathways41.

Methods

Subjects

This is an observational cohort study of subjects with a diagnosis of PD. Data used for this study are openly available from Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) database (www.ppmi-info.org/data), a multicentre, prospective, longitudinal study that aims to identify genetic, blood, cerebral spinal fluid, and imaging biomarkers of PD progression. Data used in this article were last downloaded in February 2024. Included data were acquired between Jul 1, 2010, and Jun 1, 2019, from the PPMI public database (www.ppmi-info.org/access-data-specimens/download-data), RRID:SCR_006431. For up-to-date information on the study, visit www.ppmi-info.org.42,43

The enrolment criteria for PD participants in the PPMI included the following conditions: age at baseline greater than 30 years, a diagnosis of PD within 2 years prior to the baseline visit, the presence of asymmetric resting tremor or asymmetric bradykinesia, or meeting two of the following criteria: bradykinesia, rigidity, and resting tremor44. Subjects diagnosed as PD but with a normal SPECT scan [eg Scans Without Evidence of Dopaminergic Deficit (SWEDD)], with a clinical follow-up lower than 1-year, and a neurological diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia at baseline were excluded from the analysis.

We included 560 PD subjects (mean age in years±SD: 60.97 ± 10.1; sex [F/M]: 225/335). The selected cohort had an average follow-up of 6.87 years [min/max: 1/13 years]. Among them, 128 (22.8%) carried heterozygous GBA mutations (GBA-PD), while the remaining 432 (77.1%) were GBA-negative (nonGBA-PD). The higher-than-expected frequency of GBA mutations in this population likely reflects the recruitment strategy of the PPMI study, which specifically includes genetic cohorts such as GBA-PD45.

PD subjects were further categorised based on their AAO into early-onset PD, AAO ≤ 50 years (n = 128), and late-onset PD, AAO > 50 years (n = 421)5,46.

Among the included PD, 292 subjects (GBA-PD/non-GBA-PD: 90/202) were acquired at baseline with 123I-FP-CIT-SPECT to image dopamine transporter (DAT) binding. A group of 125 healthy control subjects (HC) (mean age in years ± SD: 59.02 ± 11.5; sex [M/F]: 81/44) was selected from the PPMI as normative 123I-FP-CIT-SPECT dataset. The HC dataset showed no first-degree family history of PD, no significant neurological disorders and cognitive impairment/dementia, stable Movement Disorders Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-Part III (MDS-UPDRS-III) scores, no PD diagnosis for 6 years follow-up and were all negative for GBA1 mutations.

Clinical assessment at baseline

We included demographic, clinical motor and non-motor and neuropsychological assessments collected at baseline for each patient. Motor functions have been evaluated through MDS-UPDRS-III47. Levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was reported for each participant. We included total LEDD as the cumulative exposure to all dopaminergic drugs. Non-motor clinical assessments included the Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behaviour Disorder (RBD) Questionnaire scores (RBDSQ)48 to evaluate sleep behaviour, with RBD disorders defined as score ≥ 649, the Scale for Outcomes in PD-Autonomic (SCOPA-AUT)50 to explore autonomic dysfunction and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)51 for the assessment of depressive symptoms. Global cognition was tested with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)52, adjusted for education levels.

We also collected neuropsychological measures evaluating cognitive domains usually considered particularly impaired in PD, including t-score of Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HLVT-R)53 [for total recall, delayed recall, retention and recognition-discrimination], to assess memory; scores corrected for age and education of the Benton Judgment of Line Orientation (BJLO) 15-item version, to assess visuospatial function54; and the scaled scores of Letter-Number Sequencing (LNS)55 and t-score of semantic fluency56, to assess executive skills and working memory.

We also evaluated the presence of PD comorbidities considering concomitant medications section of PPMI. We considered patients taking anxiolytics, antidepressants, medications for delusions, hallucination, psychosis (antipsychotics), and those for cognitive dysfunction. Similarly, we defined those receiving treatment for type I and II diabetes mellitus, hypertension (e.g., high blood pressure), hypercholesterolemia, and cardiovascular events. The latter was defined as the use of medications for ischemic and/or arrhythmic heart diseases (such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, and angina) and cerebrovascular diseases (such as stroke or transient ischemic attack).

Demographic and clinical features were compared by means of Welch’s ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Differences in sex distribution in subjects stratified by GBA1 variant type were determined using one-sample tests of equality of proportions.

Genotyping

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed on DNA samples extracted from whole-blood collected according to the PPMI Research Biomarkers Laboratory Manual using Nextera Rapid Capture Exomes (Illumina) that targets 201 121 exons, untranslated regions, and miRNAs, and covers 95.3% of RefSeq exome from the human NCBI37/hg19 reference genome. The studies protocol was described in the PPMI Biological Products Manual (http://ppmi-info.org/study-design). Exons 1-11 of the GBA1 gene were Sanger sequenced. GBA1 variants were subdivided in the following classes40: “risk”, “mild”, “severe” and “unknown”. Additionally, we considered the variants G2019S and R1441G in LRRK2 as pathogenic57, as classified by the PPMI Genetics Core (Supplementary Table 1).

We conducted a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test in the GBA-PD cohort to explore the cognitive performance and dopaminergic denervation across “severe”, “mild”, and “risk” GBA variants, also exploring the interaction effect of sex.

Brain dopaminergic activity at baseline

We retrieved reconstructed imaging data related to 123I-FP-CIT-SPECT from the PPMI website. Preprocessing of SPECT brain images was conducted using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12, Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK, available at: https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/).

We retrieved reconstructed imaging data related to 123I-FP-CIT-SPECT from the PPMI website. Images were acquired using Siemens or General Electric SPECT tomographs, approximately 3–4 h after administration of the 123I-FP-CIT tracer. The imaging protocol used for PPMI scans has been previously described in refs. 42,43.

Preprocessing of SPECT brain images was conducted using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12, Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK, available at: https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/), run with MATLAB R2022b (MathWorks Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA). First, each image was spatially normalised to a high-resolution 18F-DOPA template (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/spmtemplates)43 using the old normalise function in SPM12. Parametric binding potentials were generated for each subject and voxel-wise using the Image Calculator (ImCalc) function in SPM12. The superior lateral occipital cortex was considered as the reference background region58.

Calculation of the asymmetry index (AI) was conducted following the standard formula, as described in ref. 58.

A voxel-wise multiple linear regression model was employed in SPM12 to compare GBA-PD and nonGBA-PD, and to direct compare groups within the same sex. The model included age at acquisition, asymmetry index (AI), MDS-UPDRS-III and Levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) as covariates. We set our voxel-wise significance threshold at p < 0.05 (uncorrected) and a minimum cluster extent of 100 voxels. We compared the distributions of parametric binding potentials across groups through ANCOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction, adjusted for age at acquisition, AI, MDS-UPDRS-III and LEDD.

Neural reserve calculation

We derived measures of neural reserve based on the assumption that motor symptoms and dopaminergic denervation are linearly related. The differences between these two-measure were used as operational measure of neural reserve19. In details, we performed a linear regression considering striatal dopaminergic uptake as the dependent and motor symptoms (MDS-UPDRS-III) as the independent variable of interest, adjusting for age at acquisition, AI and LEDD. Standardized residuals from the regression were then multiplied by -1 to derive W scores. Higher W scores reflect greater neural reserve, indicating that a relatively high level of brain damage is tolerated at a given level of motor symptom. Thus, we compared the distributions of W scores between the groups by Welch’s ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc correction.

Cognitive trajectories at follow-up

To assess the rate of cognitive decline over time, we calculated MoCA deflection by subtracting the baseline MoCA score from the score at the last available follow-up and dividing the result by the number of years between assessments. The current formula was already applied in previous studies to extract mini mental state examination points lost per year in clinical populations59,60,61. Between-group differences in MoCA deflection were assessed to determine if any of the four groups exhibited a faster rate of cognitive decline.

We used a linear mixed-effects model (LME) to estimate the rate of change in the MoCA scores available at each time point across: 1) males and females, 2) patients with PD who were carriers of the GBA1 mutation and those who did not carry the mutation, and 3) EO-PD and LO-PD. We also considered the interactions among all the above conditions, and we run the same set of analyses by excluding PD subjects with LRRK2 mutations. The difference between the first MoCA scores and each subsequent assessment was used as the time scale. The LME models were adjusted for age (excluding for AAO model), years of education, disease duration and MDS-UPDRS-III at baseline. The participant-specific random effect was used to account for correlations between repeated measurements from the same participants. LME has been chosen as a valuable tool to effectively handle correlated data points within the same participant, even where there are varying numbers of observations per participant, missing data, or uneven intervals between measurements62.

Moreover, we assessed the probability of remaining free from cognitive impairment using the Kaplan–Meier method and Cox regression model63. To ensure the validity of the Cox model, we tested the proportional hazards assumption, which was found to be satisfied in our analysis. This indicates that the risk ratios estimated by the Cox model are stable over time, supporting the appropriateness of this method for our study. In detail, we estimated Hazard Ratio (HR) associated with sex, GBA1 genotype, GBA variants, and AAO. We also conducted a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to investigate the combined effect of sex and GBA1 genotype on the AAO.

Survival analyses included the assessment of risk of cognitive impairment, which was defined as change in MoCA score from a baseline of >26 to the development of a score ≤ 2664. Covariates included age (excluding for AAO model), years of education, disease duration and MDS-UPDRS-III at baseline.

Not all the 560 subjects included in the study completed all control assessments regularly during the 13-year follow-up period; we identified a representative subgroup of 440 subjects (out of 560, or 78%), all with 3-year follow-up available, and with a clinical profile similar to the general population (Supplementary Tables 5–7). This strategy was adopted to improve the precision and reliability of risk estimations associated with cognitive impairment by effectively managing observation duration and minimizing bias resulting from data censoring. We choose a 3-year follow-up to maximize the number of subjects included in our analysis. We re-run the same analysis by excluding PD patients carrying LRRK2 mutations (Supplementary Table 8). The Cox Survival model was adjusted for age, disease duration, education and MDS-UPDRS-III scores at baseline.

All statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 and Python packages. The significance threshold p < 0.05 was established for all tests.

Power analysis for cognitive decline

To assess whether our study has adequate power to detect primary outcome, namely significant differences in the risk of progression to dementia among GBA1 mutation carriers compared to the general PD population, we conducted a power analysis based on (1) a previous study showing a HR of 1.76 for dementia in GBA1 mutation carriers compared to the general PD population17; and (2) prevalence of dementia in sporadic PD equal to 27.5%65 Applying these values to a standard two-proportion comparison formula, we calculated that a minimum sample size of 25 participants in the GBA-PD group would be required to detect a significant difference in dementia conversion rates with 80% power and a 5% significance level.

Responses