Uncovering the genetic variation spectrum of colorectal polyposis from a multicentre cohort in China

Introduction

According to reports, less than 10% of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients have a clear genetic correlation1. Based on different pathogenic genes, the clinical phenotypes of hereditary CRC show significant heterogeneity. Currently, hereditary CRC is mainly divided into hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, including Lynch syndrome) and hereditary colorectal polyposis based on the patient’s intestinal manifestations. Hereditary colorectal polyposis is mainly characterized by multiple polyps in the colorectum or the entire digestive tract, with a high risk of CRC development, accounting for about 1% of all CRC cases2. Hereditary colorectal polyposis can be further classified into adenomatous polyposis, hamartomatous polyposis syndrome (HPS), serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS), and hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome (HMPS) based on polyp characteristics3,4.

Adenomatous polyposis includes APC-related familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP, OMIM #175100), MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP, OMIM #608456), and other rare genetic variant-induced polyposis. Among them, FAP is the most common, a highly penetrant autosomal dominant hereditary tumor syndrome5. For classic FAP (CFAP) patients, adenomas usually begin to appear in adolescence, and there are often hundreds of adenomas and microadenomas visible during colonoscopy. If not treated in time, almost all patients will develop colorectal cancer by the age of 506. Compared with CFAP patients, attenuated FAP (AFAP) patients have fewer adenomas (10–99), later onset of disease, and more polyps distributed in the proximal colon7. In 2005, Friedl W and Aretz S collected 1166 patients clinically diagnosed with adenomatous polyposis syndrome. 76-82% of typical FAP patients carry pathogenic variations in the APC gene8. MAP is caused by biallelic variations in the MUTYH gene, manifesting as polyps throughout the colon, usually more than 10, with two-thirds of patients having fewer than 100 polyps9,10. However, there are also a significant number of patients with clinical manifestations of colorectal polyposis who cannot detect variations in APC or MUTYH. Several studies have identified multiple polyposis-related genes in families with significant co-segregation, including heterozygous pathogenic variants of POLD1/POLE11, AXIN212, and homozygous pathogenic variants of NTHL113, MBD414, MMR genes15,16.

Patients with suspected colorectal polyposis should undergo genetic screening as soon as possible to identify carriers of pathogenic germline variants and to guide clinical decision-making and family management7,17. On the one hand, members who do not carry the variant are spared unnecessary repeated testing. On the other hand, variant carriers could take preventive measures such as frequent regular physical examinations.

In recent years, sequencing technology has developed rapidly, especially next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, which has been widely applied in clinical work and has greatly promoted research on the aetiology of adenomatous polyposis. However, there are still some patients with adenomatous polyposis that cannot be explained by known genes, which is called unexplained colorectal adenomatous polyposis18.

Most of the abovementioned studies on pathogenic genes related to hereditary colorectal polyposis are from the West. There is still a significant lack of information on the detection rate of germline variants, the distribution of causative genes, and the genotype‒phenotype relationship in the Chinese population. Therefore, we conducted a multicentre clinical study to investigate the genetic spectrum of colorectal polyposis in China. An NGS panel containing 139 genes related to hereditary tumours was used to detect germline variants in the enrolled patients to establish a Chinese database of colorectal polyposis. Moreover, patients with unexplained colorectal adenomatous polyposis could be used as an entry point to explore the key pathogenic genes of adenomatous polyposis syndrome in depth.

Results

Pathogenic/likely pathogenic germline variants of key genes

Among the 120 patients enrolled patients, 78 cases (65.0%) were found to have pathogenic/likely pathogenic germline variants identified through NGS, including 75 cases of APC-related adenomatous polyposis, two cases of MUTYH-associated polyposis and one case of MSH2-related Lynch syndrome. Through MLPA, 8 patients (6.7%) were found to carry large deletions in the APC gene and 1 patient were diagnosed as GREM1-related HMPS. Two patients (1.7%) with APC promoter 1B point mutations were diagnosed via whole-exome sequencing and Sanger sequencing, as previously reported19. The clinical information of the patients, including the number of adenomas, age at diagnosis, family history, and other extra-intestinal manifestations, as well as the results of genetic testing, is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

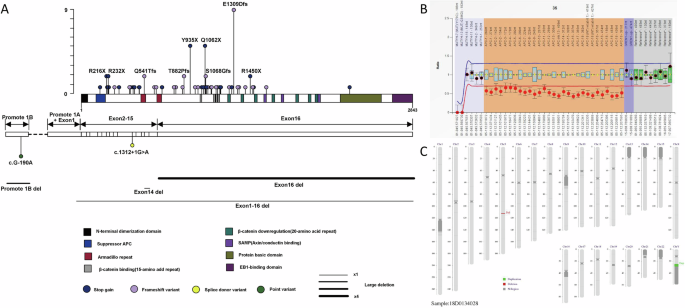

Consistent with previous reports, the APC gene was the most common pathogenic gene associated with adenomatous polyposis. A total of 85 patients were diagnosed with APC-related adenomatous polyposis. The detected APC germline pathogenic variants included frameshift variants (39 cases), stop-gain mutations (35 cases), large deletions (8 cases), point mutations in promoter 1B (2 cases), and splice donor variants (1 case). APC (NM_000038.5) contains 16 exons, of which 15 exons are involved in encoding, and most variants (65.9%, 56/85) were located in the longest exon, exon 16. The most common variants are APC c.3927_3931del p.E1309Dfs (9/85, 10.6%), APC c.2805 C > A p.Y935X (5/85, 5.9%), and APC c.3183_3187del p.Q1062X (5/85, 5.9%), as shown in Fig. 1A. According to the Leiden Open Variation Database (LOVD, https://www.lovd.nl/), the most common APC variants globally are APC c.3927_3931del p.E1309Dfs (334/6145, 5.4%) and APC c.3183_3187del p.Q1062X (212/6145, 3.4%), both of which are lower than the findings in our study. Additionally, the APC c.2805 C > A p.Y935X mutation is found in only 0.9% (53/6145) of cases, which is also significantly lower than the data presented in our study (p < 0.0001).

A Distribution of APC gene variants in each domain and mutation frequency of each variant. In the lollipop chart, the height of each lollipop represents the number of individuals carrying that variant. Similarly, the width of the lines for large deletions indicates the number of individuals carrying that variant, with the thinnest line (x1) representing 1 patient and the thickest line (x4) representing 4 patients. B The MLPA result for patient RF527. C Schematic diagram of the low-pass genome sequencing results for patient RF527; the red area represents a lack of copy number.

In addition to high-throughput NGS and MLPA, low-pass genome sequencing was used to screen for chromosomal deletions larger than 100 kb. Patient RF527, a 29-year-old man admitted with an abdominal desmoid tumour, underwent colonoscopy, which revealed 30–40 colorectal polyps. Low-pass genome sequencing revealed a deletion in 5q22.2 (GRCh37/hg19; chr5:111,851,985-112,438,322) of approximately 586.34 kb, encompassing the full length of the APC gene (Fig. 1B, C). Notably, after receiving celecoxib (400 mg daily) for two months to control fever associated with the desmoid tumour, all the colonic polyps disappeared.

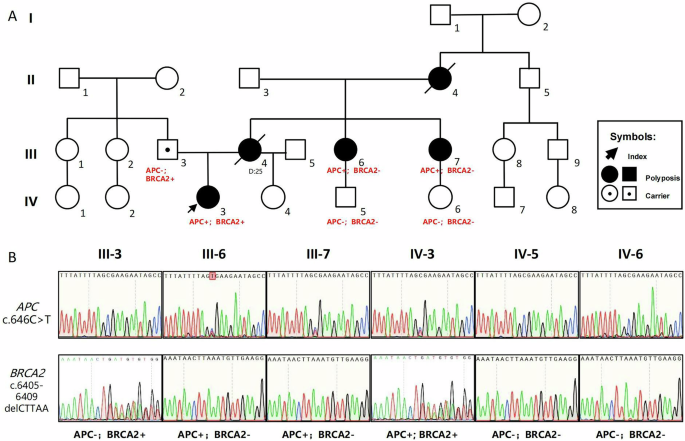

NGS could serendipitously reveal other causative variants. Patient RH613 carried both an APC nonsense variant (c.646 C > T; p.R216X) and a BRCA2 frameshift variant (c.6405_6409delCTTAA; p.N2135Kfs). Pedigree verification (Fig. 2) revealed that these variants were located on different chromatids and were inherited from the paternal and maternal lines. High-throughput NGS could facilitate the serendipitous discovery of disease-causing variants, allowing primary prevention measures to reduce the risk of disease before it occurs.

A Pedigree of patient RH613 showing the genotype and phenotype information; APC– and APC+ represent the wild type and a heterozygous stop-gain variant (c.646 C > T; p.R216X) in the APC gene, respectively. BRCA2– and BRCA2+ represent wild-type and heterozygous frameshift variants (c.6405_6409delCTTAA; p.N2135Kfs) in the BRCA2 gene. B Results of the Sanger sequencing of both the APC and BRCA2 variants.

Comparison of the mutation spectrum of colorectal adenomatous polyposis between this study and the German study

Colorectal polyposis syndrome was first studied in Germany in 1991. By 2005, the Institute of Human Genetics at the University of Bonn had analyzed APC gene variations in 1166 patients diagnosed with FAP8. Since both this study and the study by Aretz et al. included patients with more than 10 adenomas, and although Aretz et al. used Sanger sequencing combined with MLPA while we employed NGS combined with MLPA, it is important to note that NGS merely automates the detection process and does not significantly enhance mutation detection rates compared to Sanger sequencing. Therefore, despite the differences in detection methods, we suggest that a comparison of the APC mutation spectrum between the two studies remains valid. Since the phenotypic information for 137 patients was not available in the study by Aretz et al.8, we used the remaining 1029 patients for comparison with the data from this study.

The detection rate of APC gene variations in this study was 70.8% (85/120 cases), whereas it was 56.0% (576/1029 cases) in the Aretz et al. (2005), which has been shown in Table 1. In terms of APC gene mutation types (Table 2), APC protein truncation mutations caused by frameshift mutations were predominant in the study by Aretz et al. And in this study, the incidences of nonsense mutations and large fragment deletions were higher, whereas the incidences of splice mutations and missense mutations were relatively lower.

The MUTYH gene is considered the primary pathogenic mutation in patients with polyposis in whom no APC pathogenic mutations have been detected (APC-negative). Aretz et al. performed MUTYH gene mutation testing in 329 APC-negative patients and identified 55 patients (16.7%) with biallelic MUTYH mutations10. However, in our study, we found that the proportion of APC-negative patients carrying MUTYH biallelic mutations, i.e., those diagnosed with MAP, was only 5.7% (2/35), which was lower than the data from Aretz et al. (2006), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0886). In addition, the most common MUTYH mutations in the study by Aretz et al., p.Y165C and p.G382D, were not detected in this study. However, both patients with MUTYH-associated polyposis in this study carried the nonsense variant c.425 G > A, p.W142X.

Optimal number of adenomas recommended for genetic screening

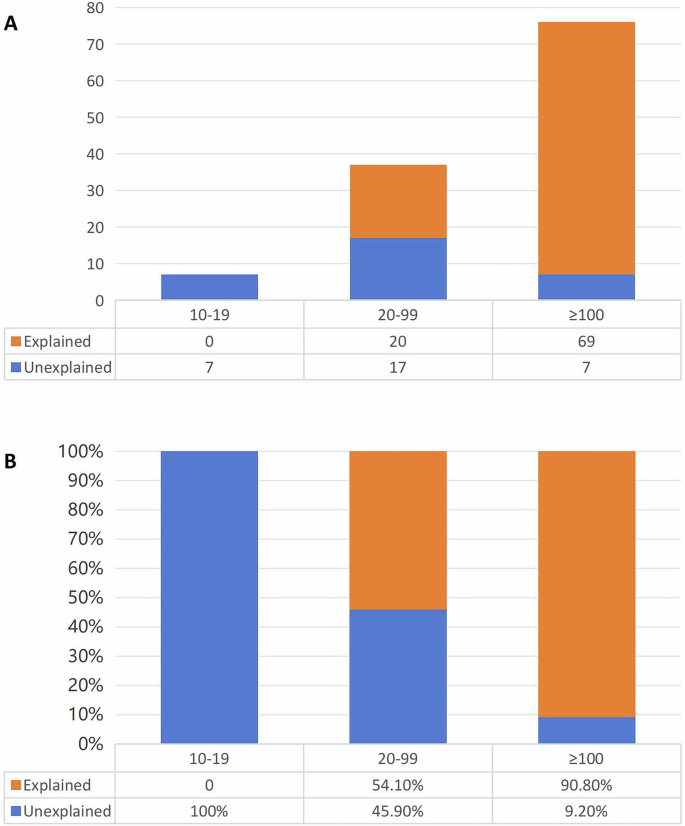

Based on the reliability and accessibility of our data on the number of adenomas in clinical practice, we divided all 120 patients into the following three groups according to the number of adenomas: 10–19 adenomas (n = 7), 20–99 adenomas (n = 37), and greater than or equal to 100 adenomas (n = 76). Then, according to whether the patients were genetically diagnosed with hereditary tumours, they were divided into an explained group and an unexplained group. The distribution of the number of patients in each group is shown in Fig. 3A. We found that the detection rate of pathogenic variants varied greatly depending on the number of adenomas (Fig. 3B). In the group of patients with greater than or equal to 100 adenomas, the diagnosis rate of hereditary tumours was as high as 90.2%. Notably, 7 patients with 10–19 adenomas were all in the unexplained group, i.e., they did not carry germline pathogenic variants in related genes. Due to the high cost of NGS for multi-gene panels in China and the psychological stress that genetic testing may impose on patients, we do not strongly recommend routine genetic testing for patients with 10-19 adenomas. Such patients can postpone genetic testing and opt for regular follow-ups, conducting genetic testing only if the number of cumulative adenomas increases to more than 20. Therefore, we suggest that a total of 20 adenomas might be the optimal number of adenomas recommended for genetic screening.

A The number of patients in each group. B The proportion of patients in each group.

Exploration of germline pathogenic variants in the unexplained group

Through NGS, MLPA and Sanger sequencing, we identified 89 patients with hereditary tumours; these patients composed the explained group, and the remaining 31 patients composed the unexplained group. Consistent with our expectations, in addition to having fewer adenomas (p < 0.0001), patients with unexplained colorectal polyposis were diagnosed at a later age (p < 0.0001), with fewer extraintestinal manifestations (p = 0.002) and a family history related to polyposis (p = 0.015), as shown in Supplementary Table 2.

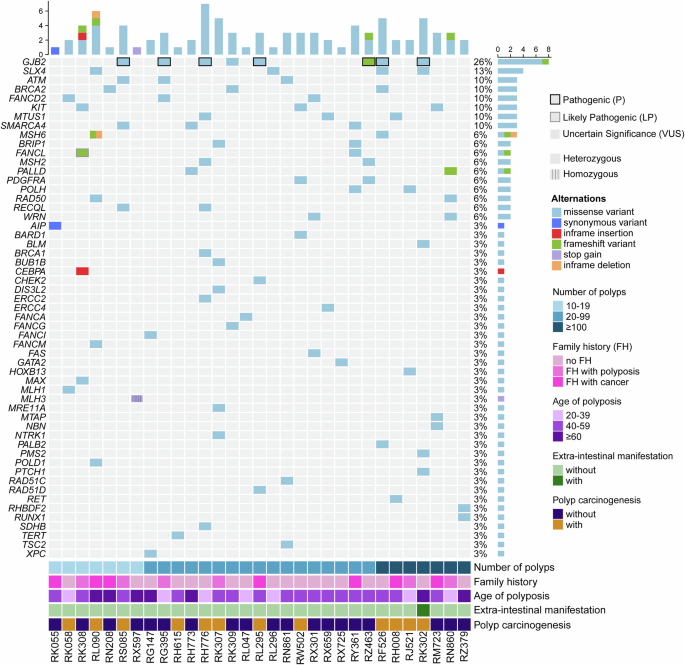

With respect to the germline variant spectrum of patients with unexplained colorectal polyposis, the NGS gene panel used in this study could detect the whole exon regions of 139 genetic susceptibility genes associated with 16 cancers and 70 genetic syndromes. All detected germline variants were scored according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) standard20. All pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), and variant of uncertain significance (VUS) genes with a mutation frequency greater than or equal to 3% are shown in Fig. 4. The most frequently mutated genes were GJB2 (25.8%, 8/31), SLX4 (16.1%, 5/31), ATM (9.7%, 3/31), BRCA2 (9.7%, 3/31), FANCD2 (9.7%, 3/31), KIT (9.7%, 3/31), MTUS1 (9.7%, 3/31), and SMARCA4 (9.7%, 3/31). We also observed some controversial gene variants, such as the homozygous nonsense variant MLH3 c.3997 C > T, p.R1333X21,22. Due to non-cooperation from the patient, we were unable to conduct the pedigree analysis; thus, we currently classify this variant as a VUS.

The black and grey frames represent pathogenic variants and likely pathogenic variants, respectively. The bottom panel shows the clinical data, including the number of polyps, age at first diagnosis, extraintestinal manifestations and polyp carcinogenesis.

We attempted to identify new pathogenic genes for adenomatous polyposis by analysing these special polyposis patients. On the basis of our previous research data23, we chose the RG395 family for whole-exome sequencing (WES) because there were multiple patients in the family and the clinical phenotype was consistent with classic FAP (more than 100 polyps). Through cell function experiments and Sanger sequencing, we believe that the DUOX2 gene may be closely related to the occurrence of adenomatous polyposis. Moreover, DUOX2 germline pathogenic mutations were also detected in two other polyposis patients (RH008 and RM723) in the unexplained group.

We subsequently analysed the pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants detected in 31 patients with unexplained polyposis. We found that 8 patients carried GJB2 variants, of which 6 carried the heterozygous pathogenic missense variant c.109 G > A p.V37I. Among the 120 patients enrolled in this study, the mutation rate was 19.4% in the unexplained group and 12.4% in the explained group. The difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.336). Therefore, we suggest that there is currently insufficient evidence to support the pathogenic or susceptibility significance of the GJB2 gene in colorectal polyposis.

In addition, we also detected a probable pathogenic FANCL variant in the unexplained group. RK308 was a 54-year-old female patient with a family history of colorectal cancer and multiple polyps (more than 10). NGS identified a heterozygous frameshift variant in the FANCL gene (c.71del; p.V24Gfs), which has never been reported in disease databases such as ClinVar and the LOVD database, or in healthy population databases such as ExAC and gnomAD. However, the frameshift variant downstream of FANCL c.71del is classified as pathogenic or probable pathogenic in the ClinVar database and pathogenic in the Varsome database. This frameshift variant prematurely terminates protein translation and consequently affects the function of this protein. In conclusion, the FANCL frameshift variant (c.71del; p.V24Gfs) was interpreted as probably pathogenic. However, after pedigree verification, we found that the variant did not show obvious cosegregation among the pedigree members, as shown in Fig. 5. Therefore, we re-evaluated the pathogenicity of the variant according to the ACMG guidelines and determined that the variant should be classified as a VUS, which has been shown in Table 3.

A Pedigree of patient RK308 showing the genotype and phenotype information; +/− represents a frameshift variant (c.71del; p.V24Gfs) in the FANCL gene, and −/− represents the wild type. B Results of the Sanger sequencing of the frameshift variant (c.71del; p.V24Gfs).

Discussion

In this study, the inclusion criterion was “10 or more cumulative adenomas throughout the colorectum”. A total of 120 patients who met the criteria were collected for genetic screening, of whom 89 were found to have germline pathogenic mutations in genes associated with hereditary colorectal cancer. Regarding the optimal number of adenomas recommended for genetic screening, most guidelines suggest more than 10 adenomas24, while some studies have set it at 2025. In this study, we found that 7 enrolled patients with 10–19 adenomas did not carry any pathogenic genetic mutations. Based on these results, we suppose that if a patient has a small number of adenomas (fewer than 20) and does not exhibit other clinical features suggestive of hereditary tumours, we do not recommend routine genetic testing for such patients, considering the potential financial and psychological burdens associated with multi-gene panel NGS testing. For these patients, we would prefer to offer them a “watch and wait” opportunity; genetic testing can be postponed; however, long-term follow-up remains necessary. If adenomas continue to occur and exceed 20, genetic testing should be conducted. Conversely, some patients have numerous polyps in their intestines. In this study, 10 such patients were included. Genetic testing revealed that all of them carried germline pathogenic mutations in the APC gene. For such patients, genetic testing is not necessary for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of the patients unless a preimplantation genetic diagnosis is needed.

As for the genetic testing methods for detecting colorectal polyposis, NGS and MLPA are the main testing methods. Among the 120 patients enrolled in this study, 78 patients with hereditary colorectal cancer were diagnosed via NGS, and through MLPA, the etiology was clarified for 9 patients with polyposis. Two patients with APC promoter 1B point mutations were diagnosed via whole-exome sequencing and Sanger sequencing, as previously reported19. In addition, three patients carried germline mutations in the DUOX2 gene. On the basis of our previous research data, we believe that germline mutations in DUOX2 are closely related to the occurrence of adenomatous polyposis23. Therefore, by using a screening approach based on an NGS platform and combining a case management model with functional experiments, the genetic diagnosis rate of colorectal polyposis increased from 72.5% (87/120, only by NGS gene panel and MLPA containing 139 genes) to 76.7% (92/120).

Regarding the characteristics of the germline mutation spectrum in Chinese FAP patients, we found that the detection rate of APC gene mutations in this study was higher than that reported in a population study by Aretz et al. in 2005. The possible reasons for this are as follows. On the one hand, the proportion of patients with classic FAP in the study population was determined. In the study by Aretz et al., 52.2% (537/1029) of the patients were CFAP patients, whereas in this study, 63.3% (76/120) of the patients had more than 100 colonic polyps. On the other hand, point mutations in the APC promoter region were not detected in the study by Aretz et al. This type of mutation was first found in 201626. In this study, a total of 2 patients with point mutations in the 1B region of the APC promoter were detected.

By conducting this clinical research, we aim not only to establish a Chinese colorectal polyposis database but also to use patients with unexplained colorectal polyposis as a starting point to explore the pathogenic mechanism of polyposis that has not yet been reported. The FANCL gene is known to be the causative gene for Fanconi anaemia, which is inherited in an autosomal recessive or X-linked mode27. It encodes a ubiquitin ligase and is a member of the Fanconi anaemia complementation (FANC) group. It is involved in mediating the monoubiquitylation of FANCD228 and FANCI29, a process that plays an important role in the DNA damage pathway. Fanconi anaemia is a rare autosomal recessive blood disorder. In this study, patient RK308, who was found to carry the heterozygous FANCL c.71delT mutation, did not currently have any blood-related diseases. In the subsequent family verification, we also found that a total of 10 individuals in the family, including the proband, carried this heterozygous mutation, of which only 2 were diagnosed with multiple colon polyps; therefore, we believe that this mutation cannot explain the multiple colon polyp phenotype of patient RK308.

This study has several limitations. First, the NGS multi-gene panel utilized did not include NTHL1 and MSH3, potentially leading to missed diagnoses of patients with NTHL1 or MSH3-related polyposis. Second, some patients had colorectal multiple adenomas diagnosed at other hospitals, and not all polyps underwent pathological review in this study to confirm adenomatous characteristics. Finally, while some reports suggest that the aetiology of certain polyposis may stem from mosaicism in APC30,31, this study did not collect adenomas, normal intestinal mucosal epithelium, or other tissues from patients, preventing any screening for mosaic cases.

This is the first multicentre clinical study on the genetic spectrum of colorectal polyposis in China involving eight participating hospitals located in different cities. Through NGS, MLPA as well as a case management model with functional experiments, we identified 92 patients with hereditary colorectal polyposis and obtained the germline variant spectrum of colorectal polyposis in the Chinese population. In terms of both the APC mutation rate and mutation type, many differences were identified in the APC mutation spectrum between this study and the data published by Prof. Aretz in 2005, as well as the global disease databases (such as LOVD). In addition, we suggest that for patients with fewer than 20 adenomas, genetic testing can be postponed, and long-term colonoscopy follow-up can be chosen. The aetiology of the remaining 28 patients with unexplained adenomatous polyposis is still worthy of further exploration, and new pathogenic mechanisms should be identified.

Methods

Patients and DNA samples

We conducted a multicentre, population-based study (NCT04961125) involving a total of 8 hospitals across the country. 120 Patients with more than 10 polyps detected via colonoscopy with pathological confirmation of adenoma were included in this study. Clinical data and pedigree information were collected. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (approval number 2017.066), the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Wenzhou Central Hospital, Air Force Medical Center of Chinese People’s Liberation Army, Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University and Jiangsu Province Hospital. Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all participants (or their parent or legal guardian in the case of children under the age of 16).

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples via the standard procedure (QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For pedigree members, if blood samples were not available, DNA was extracted from oral swabs using a TIANamp swab DNA kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China).

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and analysis

The NGS panel covers the whole exon region of 139 genes associated with 16 cancers, including colorectal cancer and 70 genetic syndromes, and it was performed by Genetron Health (Beijing, China) on the HiSeqX-ten sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). These 139 genes are shown in Supplementary Table 3. We classified germline variants according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics standards and guidelines for sequence variant interpretation32.

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

Genomic DNA samples from patients without an identified pathogenic variant by NGS analysis were examined for large deletions or duplications of the APC, MUTYH and GREM1 genes using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) (SALSA® MLPA® probe-mix P043-E1; MRC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results were analysed against controls using Coffalyser software (MRC). A dosage quotient of 0.8–1.2 was interpreted as normal; 0, 0.4–0.65 and 1.3–1.65 were interpreted as a homozygous deletion, heterozygous deletion or heterozygous duplication, respectively. For each sample, we performed 3 independent experiments.

Low-pass genome sequencing

Low-pass genome sequencing was used to screen for chromosome aneuploidy and deletions/duplications of 100 kb or more33. The genomic DNA was fragmented and purified using Axygen beads to construct a DNA library. BGISEQ-500 (BGI, Shenzhen, China) was used for continuous one-way sequencing for 35 cycles, and Zebra Call software (V1.4.0.17947) was used to read the raw data. In the analysis of the raw data, first, the data were compared with the GRCh37/hg19 genome sequence, and the observation windows were divided after removing the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) repetitive fragments. After the windows were divided, the number of reads that fell within each window was calculated, and the corresponding depth value was used to represent the fluctuation of this window to obtain the final result of the copy number variant (CNV).

Sanger sequencing

The variants were detected by Sanger sequencing according to standard protocols. The primers used for DNA amplification and sequencing are shown in Supplementary Table 4. The PCR products were purified and sequenced on an ABI 3730 DNA Analyser (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 were carried out to perform the statistical analysis. Pearson’s chi-square test was performed to assess clinical variables.

Responses