Molecular characterization of mixed-histology endometrial carcinoma provides prognostic and therapeutic value over morphologic findings

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, with an estimated incidence of 67,880 cases in 20241. Despite advances in diagnostics and therapeutics, the mortality rate has continued to rise over the last 10 years2.

While high-grade histologies only comprise 25% of EC cases, they contribute significantly to poor survival outcomes3. Mixed-histology endometrial carcinoma (MEC) is a high-grade carcinoma defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a carcinoma comprised of at least two distinct histologic subtypes that are unambiguously identifiable on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, with at least one subtype being serous or clear cell4. Notably, there is no longer a minimum 5-10% high-grade requirement based on the 2020 WHO definition, potentially resulting in more EC cases that meet diagnostic criteria than historically described. Regardless, fewer than 10% of ECs are MEC, and its rarity contributes to a paucity of data regarding clinical outcomes. The current practice trend is to treat the “worst” histologic subtype based on small retrospective studies and sub-analyses that have demonstrated any percentage of a high-grade component portends worse survival5,6,7,8,9.

Treatment algorithms and guidelines now incorporate molecular class as opposed to histology alone, as molecular classification has emerged as an opportunity for improved risk stratification of EC10,11,12,13. Furthermore, molecular classification may allow for less inter-observer variability. Even amongst gynecologic pathologists there is a high rate of reported inter-observer variability for high-grade EC histologies14,15,16. With the increasing utilization of molecular classification in EC it is important to recognize that there is limited data regarding the molecular characterization of MEC. For instance, in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) included only 13 cases of MEC, and in many other studies mixed-histologies are not separated from other non-endometrioid histologies10,11,17,18.

The primary objective of this study was to assess molecular classification in a clinically diagnosed cohort of MEC, as well as explore the role that the heterogenous histologic appearance may have on molecular class implementation. We hypothesized that molecular characterization would improve risk stratification beyond traditional histopathologic assessment.

Results

Demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of the study population

Of the 1723 patients who underwent primary surgical management for endometrial cancer during the specified timeframe, 72 (4.2%) were diagnosed with MEC on the final hysterectomy specimen and confirmed by re-review as a reasonable histologic diagnosis. Pre-operative endometrial sampling of these cases, either endometrial biopsy or dilation and curettage, only accurately diagnosed MEC in 33.3% (n = 24) cases. Of 43 patients where MEC was not captured on pre-operative sampling, 16 (37%) were originally thought to have a pure low-grade (FIGO grade 1-2) endometrioid carcinoma, and 2 (5%) were thought to have endometrial intra-epithelial neoplasia/complex atypical hyperplasia. The histologic discordance rate (mixed vs pure histology) between clinical diagnosis (confirmed by AE) and blinded pathology review (AS) was 36%, consistent with prior literature (Supplementary Table 1)14,15,16. There was no significant difference in histologic discordance based upon final hierarchical molecular class of the tumors (the percent of each molecular class that had inter-observer histologic discordance is as follows: POLE-mutated 40%, MSI-high/MMRd 32%, p53abnl 31%, NSMP 63%; p = 0.39).

Demographic and clinicopathologic information of the MEC cohort is shown in Table 1, as well as our overall institutional EC cohort and those with pure high-risk histologies (carcinosarcoma, dedifferentiated/undifferentiated carcinoma, serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, FIGO grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma). Patients with MEC and other high-risk histology endometrial cancers had a similar distribution of age, BMI, race, lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), stage, and adjuvant treatment. Despite this, the recurrence risk over a median follow-up of 47.5 months was 23.6% for patients with MEC, compared to 44.8% for the high-risk histology cohort. The recurrence risk of all endometrial cancer patients within our institutional database is 11.7%.

Molecular classification of MEC is prognostic

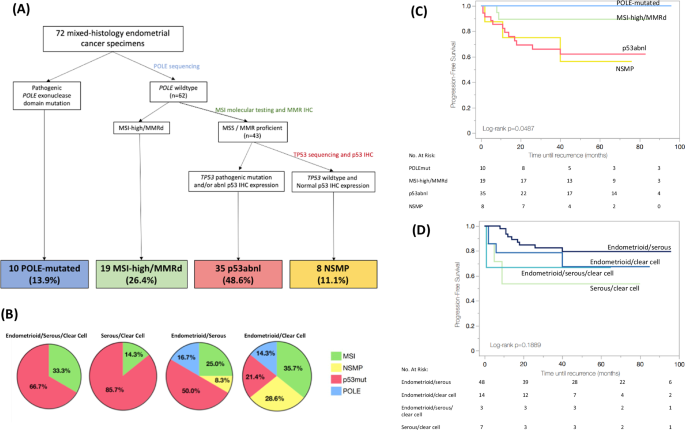

Based on all tissue testing of the representative tumor blocks, the 72 MEC tumors were ultimately molecularly classified in a hierarchical fashion as follows: 10 (13.9%) POLE-mutated, 19 (26.4%) MSI-high/MMRd, 35 (48.6%) p53abnl, 8 (11.1%) NSMP (Fig. 1A).

A Hierarchical molecular classification of mixed-histology endometrial cancer based on IHC and DNA-based tumor testing. B Relationship between histology and final hierarchical molecular classification of mixed-histology endometrial cancer. *Note that tumors classified as POLE-mutated or MSI-high/MMRd (blue or green) could have also demonstrated p53/TP53 mutation/abnormality if the tumor was a multiple classifier. Of the 58 tumors with a serous component, 11 were p53/TP53 wild-type, but of those 2 were POLE-mutated and 5 were MSI-high/MMRd. Thus, only 4/58 tumors with a serous component (6.9%) were hierarchically classified as NSMP. C Progression-free survival of patients with mixed-histology endometrial cancer based on molecular class of the tumor. D Progression-free survival of patients with mixed-histology endometrial cancer based on histologic diagnosis of the tumor.

If using a more limited methodical approach to molecular classification of MEC cases, the class breakdown differed. When utilizing only POLE sequencing and IHC, cases were categorized as: 10 (13.9%) POLE-mutated, 18 (25%) MSI-high/MMRd, 36 (50%) p53abnl, 8 (11.1%) NSMP. When utilizing only DNA sequencing, cases were categorized as: 10 (13.9%) POLE-mutated, 18 (25%) MSI-high/MMRd, 28 (38.9%) p53abnl, 16 (22.2%) NSMP. Nine (12.5%) cases were classified differently when using POLE/IHC vs sequencing only approaches. These included 1 case where MMR IHC was intact on a tumor that was MSI-high, 1 case where MMR IHC loss was detected on a tumor that was microsatellite stable (MSS), and 7 cases where p53 IHC expression was mutated in the setting of wild-type TP53 sequencing.

Demographic and clinicopathologic information for the mixed-histology cohort stratified by molecular class is presented in Table 2. Patient and tumor characteristics did not significantly differ amongst the molecular classes. While the association between histology and molecular class did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.20), we did see signals that molecular class may drive phenotype. Serous/clear cell histology was exclusively seen in MSI-high/MMRd and p53abnl tumors, and all POLE-mutated and NSMP tumors had a component of endometrioid histology (Fig. 1B). Over a median follow-up of 48 months, recurrence risk significantly differed based on molecular class. No POLE-mutated patients recurred, compared to 10.5% MSI-high/MMRd, 34.3% p53abnl, 37.5% NSMP (p = 0.047). PFS was highest for the POLE-mutated cohort (3-year PFS 100%), followed by MSI-high/MMRd (3-year PFS 89.5%), NSMP (3-year PFS 75.0%), and p53abnl (3-year PFS 65.9%); p = 0.049 (Fig. 1C). Alternatively, when tumors were classified by histology, there was no significant difference in 3-year PFS (82.5% endometrioid/serous, 78.6% endometrioid/clear cell, 66.7% endometrioid/serous/clear cell, 53.6% serous/clear cell; p = 0.1889; Fig. 1D). In multivariable analysis, molecular class (p = 0.003), stage (p < 0.001), and adjuvant treatment (p = 0.001) were independently associated with PFS (Table 3). Survival outcomes remained similar when the cohort was limited to only those tumors confirmed to be MEC by the second blinded pathology review (AS) (n = 46; Supplementary Fig. 2).

Challenges to assigning molecular classification in MEC: subclonal/heterogenous staining, discordance between IHC and sequencing, and multiple classifiers

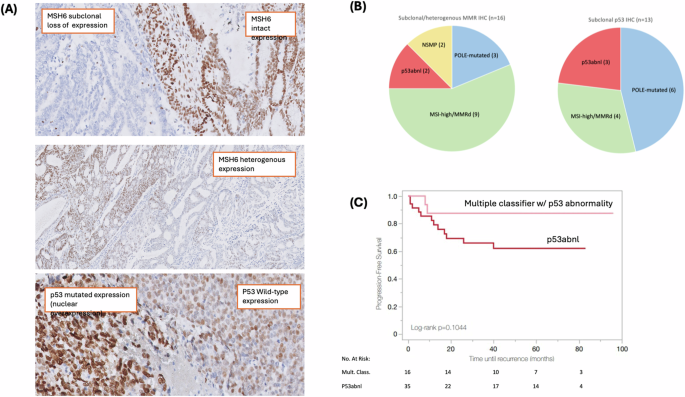

Subclonal IHC expression of p53 was seen in 13 (18%) cases, and this was most common in the POLE-mutated tumors (6 POLE-mutated, 4 MSI-high/MMRd, 3 p53abnl, 0 NSMP; p = 0.001). A subclonal p53 expression pattern was seen in 3 (9%) p53abnl tumors, all of which were confirmed to have a TP53 pathogenic mutation on sequencing (Fig. 2A, B). Twenty-three of 72 tumors had a discordance between p53 IHC and TP53 sequencing (32% discordance rate). When repeat IHC and sequencing were performed on a representative tumor block, the discordance resolved in 11 cases, yielding a 17% discordance rate (Supplementary Fig. 1). Of the remaining discordant cases, 6/12 were either POLE-mutated or MSI-high/MMRd tumors.

A Representative examples of abnormal MMR and p53 immunohistochemical staining patterns, including subclonal MSH6 expression (top), heterogenous MSH6 expression (middle), and subclonal p53 expression (bottom). B Molecular class breakdown of abnormal IHC expression patterns seen in mixed-histology tumors. C Progression-free survival of patients with multiple classifier tumors harboring TP53/p53 abnormality vs p53abnl tumors.

Of 35 tumors ultimately classified as p53abnl, 8 had different p53 IHC expression patterns in different histologic components of the tumor. Most of these (n = 7) had a serous component that demonstrated a mutated p53 IHC expression pattern, and an endometrioid component that was p53 wild-type. In one case, the endometrioid component had a subclonal p53 IHC expression pattern, and the clear cell component was p53 wild-type. All of these cases had TP53 mutation on DNA sequencing.

Subclonal and/or heterogenous IHC expression of MMR proteins was seen in 16 (22%) cases. Of these 16 tumors, most (n = 9) were classified as MSI-high/MMRd, 3 were POLE-mutated, 2 were p53abnl, and 2 were NSMP (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2A, B). IHC expression patterns for the MSI-high/MMRd cohort are described in detail in Supplementary Table 3. Subclonal and/or heterogenous MMR IHC expression was seen in 47% of MSI-high/MMRd tumors, most often with concurrent complete loss of an additional MMR protein. Only 2 tumors had an isolated subclonal MSH6 expression pattern, and 1 tumor had an isolated heterogenous MLH1/PMS2 expression pattern (all 3 cases were confirmed to be MSI-high on molecular testing).

Nine of the 72 tumors had a discordance between MMR IHC and microsatellite testing (12.5% discordance rate). When repeat IHC and MSI testing were performed on a representative tumor block, the discordance resolved in 8 cases, yielding a 1.4% discordance rate (Supplementary Fig. 1). The one remaining case of discordance between MMR/MSI testing was a POLE-mutated tumor which was reported in our prior publication19.

Of 19 tumors that were ultimately classified as MSI-high/MMRd, only 2 had different MMR IHC expression patterns in different histologic components of the tumor. In both cases, the endometrioid component demonstrated subclonal MSH6 loss, while the other component was either intact (1 clear cell) or had complete MSH6 loss (1 serous). Both cases were MSI-high on molecular testing.

Additionally, of the 19 MSI-high/MMRd cases, 36% (n = 7) were found to have an epigenetic MMR defect, whereas 63.2% (n = 12) had a probable MMR mutation (Supplementary Table 3); this is in stark comparison to 84% of our overall institutional cohort having an epigenetic MMR defect19. Tumors with a probable MMR mutation were most likely to have abnormal MSH6 IHC expression (n = 7/12). There were 4 tumors with MLH1 IHC abnormality that were not hypermethylated. Both patients with MSI-high/MMRd tumors that experienced disease recurrence had a probable MMR mutation.

Sixteen (22%) tumors were identified as having more than one molecular class feature, which is higher than previously reported (3%) in unselected cohorts20. By hierarchical molecular classification, 6 were POLE-mutated and 10 were MSI-high/MMRd. All multiple classifier tumors had a TP53 mutation and/or abnormal p53 IHC. Two tumors had alterations in all three POLE, MSI/MMR, and TP53/p53. Tumors with multiple molecular alterations had high rates of subclonal and/or heterogenous MMR IHC expression (44%) and subclonal p53 IHC expression (62.5%). Despite all multiple classifier tumors having a TP53/p53 alteration, the recurrence rate was only 10.5% (n = 2) as compared to a 34% recurrence rate for patients with tumors classified as p53abnl. A trend toward improved PFS was noted for the limited number of patients with multiple classifier tumors as compared to p53abnl tumors, although this was not statistically significant (3-year PFS 87.5% vs 65.9% for multiple classifiers vs p53abnl; p = 0.10) (Fig. 2C).

Additional molecular and transcriptional data provide biologic insight and potential therapeutic implications

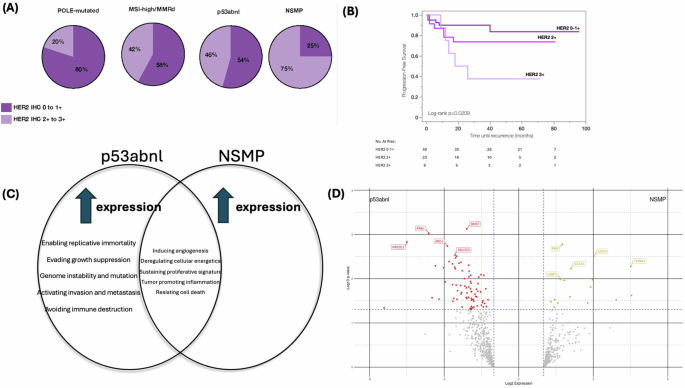

HER2 IHC scores for the MEC cohort were 12.5% (n = 9) 3 + , 32% (n = 23) 2+, 40% (n = 29) 1+, 15% (n = 11) 0. Seven tumors were noted to have differential HER2 expression per histotype (5 endometrioid/serous, 2 serous/clear cell). Numerical HER2 IHC score was significantly associated with molecular class, where those tumors that had a score of 3+ were most likely to be p53abnl (77.8%), as opposed to POLE-mutated (11.1%), MSI-high/MMRd (11.1%), or NSMP (0%) (p = 0.042; Supplementary Table 4). A HER2 IHC score of 2–3+ was noted in 20% (n = 2) of POLE-mutated tumors, 42% (n = 8) of MSI-high/MMRd tumors, 45% (n = 16) of p53abnl tumors, and 75% (n = 6) of NSMP tumors (Fig. 3A). Numerical HER2 IHC score was not associated with histology (p = 0.885; Table 3). HER2 IHC score was significantly associated with PFS (3-year PFS 90% for score 0-1+ vs 74% for score 2+ vs 37.5% for score 3+; p = 0.021; Fig. 3B). HER2 IHC score remained predictive of PFS on multivariable analysis when controlling for molecular class, stage, and adjuvant treatment (p = 0.018; Table 3).

A HER2 IHC score breakdown by molecular class. B Progression-free survival of patients with mixed-histology endometrial carcinoma based on HER2 IHC score. C Differential gene expression between p53abnl and NSMP tumors demonstrated differences in themes of tumor biology, immune response, and microenvironment remodeling using the NanoString nCounter® Tumor Signaling 360™. D Volcano plot showing differential gene expression between p53abnl and NSMP tumors. Differential gene expression was determined significant if fold change (log2 ratio) was greater than ±1.5, and p-value < 0.05, and is represented by the colored dots. The 5 most significant differentially expressed genes are labeled based on log10p-value.

Immunohistochemical staining for ER status was clinically performed on 22 tumors (n = 21/65 tumors that had an endometrioid component). Of these, 18 (82%) were ER positive, and 4 (18%) were ER negative. Six cases were noted to have differential ER expression per histotype with positive expression in the endometrioid component and negative expression in the serous or clear cell component. Of the 4 cases that were ER-negative, 2 were p53abnl tumors and 2 were NSMP tumors. All 4 patients with ER negative tumors were diagnosed with disease recurrence during follow-up. Of the 18 cases that were ER-positive, 1 (6%) was POLE-mutated, 9 (50%) were MSI-high/MMRd, 2 (11%) were p53abnl, and 6 (33%) were NSMP (p = 0.10). Three of the 18 (17%) ER-positive tumors were diagnosed with disease recurrence during follow-up (n = 2 MSI-high/MMRd, 1 NSMP).

Given the similar aggressive histologic appearances and poor clinical outcomes of the p53abnl and NSMP MEC tumors, we sought to evaluate transcriptome-level data to determine whether there were differences in gene expression. Fourteen tumors (10 p53abnl and 4 NSMP) underwent analysis. The 10 p53abnl tumors were endometrioid/serous (n = 4), endometrioid/clear cell (n = 1), serous/clear cell (n = 4), endometrioid/clear cell/serous (n = 1). The 4 NSMP tumors were endometrioid/serous (n = 2) and endometrioid/clear cell (n = 2). When compared with the NSMP tumors, those that were p53abnl had increased expression of genes that are involved in activating invasion and metastasis, avoiding immune destruction, enabling replicative immortality, evading growth suppression, and genome instability (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Table 5). Ninety-three differentially expressed genes were identified between p53abnl and NSMP tumors (Fig. 3D; Supplementary Table 6). Genes that were the most significantly differentially expressed and upregulated in p53abnl tumors were associated with evasion of the innate immune response (ARG1, SIGLE5, KIR2DL3), evasion of growth suppression (MKI67), and interferon response (IFNA1). Additional upregulated genes in the p53abnl tumors were noted to be associated with evasion of the innate immune response specifically by natural killer (NK) cell mechanisms (KIR2DL3, KIR3DL1, KIRDL2, NCR1). There were also several genes upregulated in p53abnl tumors that were associated with DNA damage repair (CLSPN, BRIP1, BLM, EME1, H2AX, PARP2, KPNA2). Genes that were the most significantly differentially expressed and upregulated in NSMP tumors were associated with tumor cell proliferation and survival (TSPAN1, PKM), tumor cell migration/metastasis (UGDH), regulation of cytokine release (SOCS1), and apoptosis (CASP3). No genes upregulated in NSMP tumors were associated with evading the immune response. Thus, while the molecular classification might not provide an opportunity for prognostic refinement it may suggest opportunities for therapeutic exploration in these high-risk histology tumors.

Metastatic and recurrent disease histologic and molecular features

Twenty-six patients were identified as having 31 metastatic and/or recurrent tissue specimens available for analysis. Few (17%) metastatic/recurrent specimens had two identifiable histotypes on pathologic assessment. When one histotype metastasized, it was infrequently endometrioid (16% of primary endometrioid/serous tumors, 17% of primary endometrioid/clear cell tumors; Supplementary Fig. 3).

Molecular classification of tumors from the 26 patients with metastatic/recurrent disease was as follows: 2 (8%) POLE-mutated, 10 (38%) MSI-high/MMRd, 11 (42%) p53abnl, and 3 (12%) NSMP. Most cases (n = 21, 81%) had congruence between IHC of the primary tumor and the recurrent/metastatic specimen (Supplementary Fig. 3B). One of 10 patients with a primary tumor classified as MSI-high/MMRd (MLH1/PMS2 heterogenous, MSI-high) had intact MMR IHC on both a metastatic and a recurrent tissue specimen. There were 4 cases where the primary specimen from an MSI-high/MMRd tumor had abnormal p53 IHC expression (multiple classifier) that was not observed in the metastatic/recurrent tissue specimen (i.e. the metastatic/recurrent tissue specimen was p53 wild-type) Otherwise, molecular features analyzed via IHC were congruent between primary and metastatic/recurrent specimens.

Discussion

Dedicated studies of MEC are limited; given the rarity of these tumors, they are often grouped together with other “non-endometrioid” histologies. Here we report clinicopathologic findings and molecular characterization of one of the largest cohorts of clinically diagnosed MEC to our knowledge. Molecular classification of MEC was able to risk-stratify patients and may be an opportunity to improve individualized patient counseling by removing some of the inter-observer challenges including histologic reproducibility in high-grade EC14,15,16. Several important observations in this cohort included high rates of POLE mutations, MSI-high/MMRd tumors with probable MMR mutation, multiple classifiers, and subclonal alterations. Importantly, patients with p53abnl and NSMP tumors have similarly poor outcomes, although transcriptome analysis highlighted biologic differences that may guide further study for differential therapeutics. Additionally, HER2-targeting agents are emerging as an important therapeutic opportunity for patients with EC and in this cohort, we observed high rates (44.4%) of HER2 2+ and 3+ tumors regardless of molecular class.21,22. We also highlight several important challenges to implementing molecular classification in MEC including the selection of representative tumor blocks and hierarchical classification.

Prior reports have utilized different combinations of DNA-based and histologic methods to molecularly classify EC10,11. Recognizing the potential challenges of heterogenous MEC tumors, we performed both a DNA and histologic approach to capture any molecular alterations that may be driving tumor appearance and behavior. Indeed, the high rate of multiple classifiers, discordance between molecular and histologic testing, and subclonal/heterogenous expression patterns made molecular classification of MEC difficult to interpret. Twenty two percent of MEC tumors had more than one molecular alteration, which may be inappropriately classified if a complete, hierarchical approach is not utilized. The excellent survival of multiple classifiers in our study is consistent with previously published literature and indicates that these tumors should not be treated on the basis of a p53 abnormality alone20,23. When molecular and histologic testing was performed on a representative tumor block, the MMR/MSI discordance rate (1.4%) was like previously published reports19,24. The p53/TP53 discordance rate (17%) was higher than prior literature, but we suspect this may be driven by the large number of POLE-mutated and MSI-high/MMRd tumors in our study25,26. Additionally, the rates of subclonal and/or heterogenous MMR (22%) and subclonal p53 (18%) IHC were high in MEC tumors. In the absence of other molecular alterations, these have previously been described to be consistent with MSI-high/MMRd and p53-mutated phenotypes, respectively19,25,27,28. Expert pathologist input is critical for recognizing abnormal expression patterns and selecting representative tumor blocks for tissue testing to optimize the molecular classification of MEC.

Additionally, it may be beneficial to employ both a DNA-based and histologic approach when a heterogenous tumor is encountered to capture any existing molecular abnormalities.

Utilizing a DNA and histologic approach we were able to hierarchically molecularly classify MEC, with a different breakdown than had been previously reported for unselected endometrial cancer populations10,11. Fourteen percent of tumors were POLE-mutated (compared to 7.3% TCGA, 9% ProMisE), 27% MSI-high/MMRd (compared to 28% TCGA, 29% ProMisE), 49% p53abnl (compared to 26% TCGA, 18% ProMisE), and 11% NSMP (compared to 39% TCGA, 45% ProMisE). Interestingly, the MSI-high/MMRd cohort had better outcomes than previously reported, where studies have demonstrated that survival curves tend to overlap with the NSMP class10,11,29,30. We anticipate that this is related to the high percentage of probable MMR mutations (63%) in the MEC cohort, as epigenetic MMRd is associated with higher rates of metastatic disease and worse survival31,32. The survival of the patients with MSI-high/MMRd tumors in our cohort is not explained by immunotherapy treatment, as our study predated the impressive survival benefit noted in the experimental arms of the RUBY, NRG-GY018, and KEYNOTE-B21 trials, and no patients received immunotherapy in the adjuvant setting33,34,35. Demographic and clinicopathologic features were similar amongst molecular classes of MEC, with the only significant difference being recurrence risk (0% POLE-mutated, 10.5% MSI-high/MMRd, 34% p53abnl, 37.5% NSMP; p = 0.047). These recurrence rates are like those previously reported for molecularly classified high-grade endometrial cancers, independent of clinicopathologic features36. Molecular class, in addition to stage and adjuvant treatment, remained independently associated with progression-free survival on multivariable analysis (p = 0.003), while histology was not prognostic (p = 0.189), indicating that molecular class more accurately risk-stratifies patients than morphologic findings.

Additional molecular data that may be readily clinically applicable via IHC, including ER and HER2, provide additional prognostic information and therapeutic implications for patients with MEC. ER IHC was clinically performed on 22 tumors, most of which were ER-positive. Of the 4 tumors that were ER-negative, the recurrence rate was 100% compared to 17% for the 18 tumors that were ER-positive. While small numbers, this provides an interesting contrast to current data, which supports the prognostic value of ER status only for low-grade NSMP tumors37,38. A significant proportion of MEC tumors had a HER2 IHC score of 2–3+, comparable to rates previously reported for endometrial serous carcinoma39,40. A recent analysis of the PORTEC-3 cohort demonstrated higher concordance between HER2 positivity and p53 mutational status than serous histology41. Additionally, in the TCGA cohort all ERBB2-amplified tumors were in the copy number-high group10. In our MEC cohort, we found that HER2 positivity was not limited to p53abnl tumors. Of 32 MEC tumors with HER2 IHC score 2–3+, only 16 (50%) were p53abnl; 2 (6%) were POLE-mutated, 8 (25%) were MSI-high/MMRd, and 6 (19%) were NSMP. While there is some data that suggests approximately 37% of MSI-high/MMRd tumors are HER2 positive in colorectal cancer, this has not been supported to our knowledge in EC, where all 135 MMRd tumors in the PORTEC-3 sub-analysis were HER2 negative41,42. Additionally, histology did not significantly correlate with HER2 IHC score in our cohort of MEC tumors. In the study by Vermij et al., the authors argue for molecular subclass-directed HER2 testing as opposed to histologic-directed HER2 testing. We advocate for HER2 testing of all MEC given the high rate of HER2 positivity across molecular and histologic subtypes, especially given the therapeutic implications considering the recently published DESTINY trial, where unprecedented response rates to the antibody-drug conjugate trastuzumab deruxtecan were seen for recurrent HER2-3+ endometrial cancer22.

While the molecular classification of MEC provided improved risk-stratification as compared to morphologic findings alone, similarly poor survival outcomes were noted for both the p53abnl and NSMP cohorts. We evaluated a subset of these tumors at the transcriptome level to better understand differences in biologic behavior. Whole-transcriptome analysis suggested that p53abnl tumors had relatively increased expression of genes involved in avoiding immune destruction, particularly involving NK cell mechanisms, and genome instability/mutations. While hypothesis-generating, this data may serve as background for therapeutic targeting based on molecular class, where p53abnl tumors may benefit from drugs that promote NK cell function or potentially exploitation of PARP inhibitor use. The later may be supported by pan-tumor TCGA analysis that has shown a significant correlation between mutations in homologous recombination repair-related genes and TP53 mutation43. The DUO-E trial recently looked at the addition of PARP inhibitor maintenance to immunotherapy and chemotherapy in advanced/recurrent endometrial cancer, however it did not incorporate p53 status44.

Patterns of metastatic and recurrent disease in MEC tumors further supported our hypothesis that molecular characteristics drive behavior more than morphologic findings. Most metastatic/recurrent tissue samples only had one identifiable histotype (17% endometrioid, 83% serous or clear cell). Of the 26 patients with metastatic/recurrent disease, IHC was representative of the molecular class of the primary tumor in 96% of cases. There were 4 MSI-high/MMRd tumors that were multiple classifiers with p53 IHC abnormality of the primary tumor that did not carry over to the metastatic/recurrent specimen. For all 4 of those cases, the p53 IHC abnormality in the primary tumor was either subclonal (2) or located within one histotype only (3). This may provide further support for the argument that those tumors that are multiple classifiers have behavior that is driven by molecular hierarchy, where p53 mutations are a bystander effect resulting from mismatch repair deficiency or POLE mutation20.

The histologic diagnosis of high-risk histology EC is challenging. Diagnostic challenges start with pre-operative endometrial sampling, which in our cohort only accurately diagnosed 33% of patients with MEC. Of the remaining cases that were not known to be MEC pre-operatively, 37% were suspected to have low-grade carcinoma and 5% were suspected to have endometrial intra-epithelial neoplasia/complex atypical hyperplasia. Even once the final pathology is available for review, there is well-established high inter-observer variability in the histologic diagnosis of high-grade EC14,15,16. While molecular and IHC data may provide clinical context, reliance upon traditional IHC markers for histologic diagnosis should be cautioned. Wild-type p53 IHC was noted in 19% of MEC tumors that were felt to have a serous histologic component (Fig. 1B), consistent with prior data demonstrating that only 75% of serous tumors are p53/TP53 mutated45. Additionally, a significant proportion of these tumors in our study were either POLE-mutated or MSI-high/MMRd. With the distinct molecular breakdown of our MEC cohort including high rates of POLE mutations and probable MMR mutations, the observation that molecular features may drive morphology is certainly an argument for considering molecular class over histologic appearance in risk stratification. It has been well reported that both POLE-mutated tumors and MSI-high/MMRd exhibit higher rates of high-grade appearance and given the inter-observer variability, a “mixed” histologic appearance may in fact be in the eye of the beholder in some cases. In fact, when a second, blinded gynecologic pathologist re-reviewed our clinically diagnosed MEC cases through a contemporary lens, the histologic concordance rate was only 64%. This begs the question of whether molecular classification can better characterize MEC for diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic purposes.

Our study has important limitations to address. First, and likely the most important, the inclusion of MEC was limited to clinically diagnosed cases from a surgical endometrial cancer database. Recent changes in the understanding and pathologic assessment of EC, or review by a different pathologist, may have resulted in alternative diagnoses that would preclude inclusion. Based on a blinded review by a second pathologist through a contemporary lens, approximately 1/3 of cases in our cohort may not have been classified as true MEC. We felt that it was important to include all clinically diagnosed cases of MEC in our study (as opposed to only those confirmed by a blinded review of a single pathologist), as the rate histologic discordance/inter-observer variability is significant in high-grade endometrial cancer. While a real-world practice likely consults multiple pathologists for challenging or ambiguous cases, our cohort is representative of a real-world MEC population where this data is most applicable. Additionally, as this was a retrospectively identified cohort, we were not able to control for pre-analytic variables including cold ischemia time, formalin fixation time, and tissue processing. Finally, the lack of available tissue for most pre-operative endometrial specimens prevented us from being able to molecularly characterize and compare pre-operative to hysterectomy specimens, and limited tumor tissue of metastatic/recurrent specimens precluded DNA analysis in this setting where we relied upon IHC for molecular data.

In summary, MEC is a unique cohort of EC with heterogeneity that has historically contributed to diagnostic dilemmas on the basis of morphology. Molecular classification of MEC, although with its own challenges in implementation, provides improved risk stratification for patients with better reliability than histology alone. Even for those patients with poor survival outcomes, biologic differences between molecular class may drive the development of targeted therapeutics. In particular, the high HER2 positivity rate of these tumors across molecular classes is novel, and exciting in the era of HER2-targeting therapies.

Methods

Patient and tissue selection

The Institutional Review Board and the Comprehensive Cancer Center Clinical Scientific Review Committee at The Ohio State University approved this study (IRB No. 2021C0163). A waiver of consent was granted by the institutional ethics committee given the retrospective nature of the study and utilization of archival tissue from previously obtained surgical specimens. This study was also performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. A review was performed of all patients who underwent surgical management of EC at our institution from 2014–2020 (n = 1723). Cases were screened for inclusion based on the final pathology diagnosis of MEC on the hysterectomy specimen (n = 75, 4.4%, two of which cases were included in a previous publication)19. Histology slides for each case were re-reviewed by a single gynecologic pathologist [AE] including assessment of morphologic and immunophenotypic features in order to confirm that the case reasonably met the criteria for MEC based on the definition set by the World Health Organization4. Following review, 3 cases were excluded from the final analysis due to re-classification as carcinosarcoma (n = 1), re-classification as fallopian tube primary (n = 1), and inadequate tumor tissue for testing (n = 1). A second gynecologic pathologist [AS] blinded to the clinical diagnoses reviewed the cases as well to determine inter-observer histologic concordance rate (Supplementary Table 1). We did not exclude cases from the study based on the blinded review, as we wanted to assess clinically diagnosed cases that reasonably met criteria for MEC, as this represented the population of interest. Clinicopathologic data from these cases were abstracted from the electronic medical record.

Tumor tissue for molecular and morphologic testing was selected from the hysterectomy specimen for each case based on the pathology report. If molecular discrepancies were noted between immunohistochemistry (IHC) and DNA-based molecular testing (i.e. MMR deficient IHC expression pattern but microsatellite stable on molecular testing; or p53-mutated IHC expression pattern but TP53 wild-type on Sanger sequencing), then a repeat tissue block felt to be representative of the tumor was selected by the gynecologic pathologist from the hysterectomy specimen and repeat IHC and molecular testing were performed, with emphasis to ensure DNA extraction and IHC characterization of all tumor histologic components. Additional tissue blocks from metastatic, non-uterine and/or recurrent disease were also selected for ancillary testing, where applicable. Most sites of metastatic/recurrent disease contained minimal residual tumor tissue available for ancillary analysis.

Morphologic characterization

Gynecologic pathologist review of histology slides resulted in the characterization of morphologic features including histologic subtype (endometrioid/serous, endometrioid/clear cell, endometrioid/serous/clear cell, serous/clear cell), International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) grade of endometrioid subtype (where applicable), pattern of mixed-histology (biphasic [distinct separation of histologic subtypes] vs intermixed [lack of distinct delineation between histologic subtypes]), presence and appearance of immune infiltrate, and correlation with pre-operative histology (endometrial biopsy or dilation and curettage specimen, where applicable).

DNA extraction and sequencing

DNA was isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) slides through deparaffinization, digestion with proteinase K, and purification using the Quick-DNA FFPE Kit (Zymo Research, Tustin, CA, USA), and quantified with the Qubit Fluorometric Quantification system (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). When extracting DNA, we emphasized scraping tissue from all histologic components of the tumor block for FFPE to ensure sequencing results were representative of the entire tumor. PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing of POLE and TP53 genes were performed as previously described, with a few modifications as follows46. POLE status was determined by targeted sequencing of exons 9, 13, and 14 of the exonuclease domain, which covers 9 of the 11 pathogenic POLE mutations as defined by Leon-Castillo et al. 47. TP53 status was determined by targeted sequencing of exons 4-10. Pathogenicity was determined based upon “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” classification by at least two in silico models (Clinvar, PolyPhen-2, Ensembl, COSMIC). Primers utilized for POLE and TP53 sequencing are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Microsatellite molecular testing

Molecular testing for microsatellite instability (MSI) was performed on all cases using the National Cancer Institute five-plex assay, assessing the markers BAT25, BAT26, D2S123, D5S2346, and D17S25048. Tumors were classified as MSI-high if novel alleles were detected at ≥2 loci, and MSI-low if a novel allele was detected at only 1 locus. All cases that were MSI-low, demonstrated subclonal or heterogenous mismatch repair (MMR) protein expression, and/or had discrepancy between MSI testing and MMR IHC underwent repeat MSI testing (and repeat MMR IHC) on a representative tumor block. Confirmatory MSI testing was performed using Promega MSI Analysis System version 1.2 (Promega, Madison, WI), assessing the mononucleotide repeat markers BAT25, BAT26, MONO27, NR21, and NR24, and the pentanucleotide repeat markers PentaC and PentaD. Genetic testing including germline and/or somatic results were also recorded if performed clinically.

MLH1 methylation analysis and subclassification of MSI-high/MMRd tumors

Methylation-specific PCR was utilized as a clinical reflex test to assess the mut-L homolog 1 (MLH1) methylation status of tumors with loss of MLH1/PMS 1 homolog 2 (PMS2) as detected on IHC. MLH1 methylation testing was also utilized for research purposes on additional samples that were found to have abnormal MLH1 IHC expression patterns upon a gynecologic pathologist re-review of cases, as previously reported19. MSI-high/MMRd tumors that were found to have hypermethylation of the MLH1 promoter were further classified as having an epigenetic MMR defect. Those without MLH1 promoter hypermethylation were classified as having a probable MMR mutation (probable Lynch syndrome or somatic mutation).

Immunohistochemical staining and evaluation

IHC for MMR proteins (MLH1, PMS2, mut-S homolog 6 [MSH6], mut-S homolog 2 [MSH2]), p53, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) was evaluated for each case by a gynecologic pathologist by either re-review of clinically performed IHC, or retrospective staining of FFPE from the representative tumor block, ensuring analysis of all histologic components. FFPE blocks were cut into 4 µm slides and stained for IHC using the following antibody clones: MLH1, ES05 at 1:200 dilution (Leica/Novocastra) or M1 ready to use (RTU) (Roche); MSH2, FE-11 at 1:200 dilution (Calbiochem) or G219-1129 RTU (Roche); MSH6, ep49 at 1:200 dilution (Epitomics) or SP63 RTU (Roche); PMS2, A16-4 at 1:100 dilution (BD Pharmingen) or A16-4 RTU (Roche); p53, DO7 at 1:1000 dilution (Dako/Agilent); HER2, 4B5 RTU (Dako/Agilent). IHC for estrogen receptor (ER) was evaluated by a gynecologic pathologist by re-review of clinically performed IHC, where applicable; at our institution the following antibody clone is used: ER, SP1 at 1:600 dilution (Abcam).

Results for MMR proteins were reported as either “complete loss,” “subclonal loss,” “heterogenous,” or “intact.” Tumors with any positive reaction in the tumor cell nuclei were considered intact based on IHC interpretation guidelines of the College of American Pathologists (CAP)49. Subclonal loss was defined as abrupt, complete loss of expression of an MMR protein (comprising at least 5% of tumor cells) within a histotype, in the presence of a positive internal control, as previously reported19,27. The term heterogenous expression was utilized when areas of weak/absent staining and areas of strong/diffuse staining were intermixed and not distinctly delineated within the tumor27. Due to concern that the few tumors with isolated heterogenous MMR IHC expression were potentially related to tissue processing variables (cold ischemia time, fixation, and others), these tumors were molecularly classified on the basis of MSI testing. Subclonal or heterogenous expression patterns were defined as occurring within one histologic subtype of the tumor, or could have been observed throughout all histologic subtypes.

Results for p53 were reported as “mutated,” “subclonal,” or “wild-type.” A mutated expression pattern was defined as an aberrant strong diffuse positive expression in >80% of tumor nuclei (overexpression), complete absence of expression in the presence of positive internal control (null phenotype), or cytoplasmic expression only. Wild-type expression was defined as p53 staining of 1-80% of nuclei with variable intensity and extent. Tumors with subclonal p53 had wild-type expression with abrupt aberrant mutated expression pattern comprising at least 5% of tumor cells within one histotype, or could have been observed throughout all histologic subtypes25,50. Tumors with subclonal p53 expression in the absence of any other molecular alteration were classified as p53 abnormal (p53abnl) based on prior data25.

Results for ER status were reported as “positive” or “negative” based upon CAP guidelines for biomarker reporting in endometrial cancer49. Negative ER staining was defined as the presence of <1% immunoreactivity of tumor cells. HER2 IHC was scored from 0 to 3+ based on current American Society of Clinical Oncology/CAP guidelines for scoring HER2 in gastric cancer51. If differential HER2 expression was noted between histologic subtypes within a tumor, the tumor was classified based on the highest HER2 IHC score.

Molecular classification

As described above, each case underwent DNA sequencing for POLE, MMR IHC and MSI molecular testing, and p53 IHC and DNA sequencing for TP53. Based upon these results, tumors were molecularly classified into the following groups: POLE-mutated, MSI-high/MMRd, p53abnl, or no specific molecular profile (NSMP; POLE wild-type, microsatellite stable/MMR intact, p53 wild-type), paralleling those described by TCGA and ProMisE10,11. If more than one molecular alteration was identified, tumors were hierarchically classified as previously described20. If MMR IHC and MSI testing were not concordant for a case, repeat IHC and MSI testing were performed on a representative tumor block as previously described. If results were still not concordant, the tumor was ultimately classified as MSI-high/MMRd based upon the presence of any abnormal molecular testing or complete/subclonal loss of MMR proteins on IHC (Supplementary Fig. 1a). If p53 IHC and TP53 sequencing results were not concordant, repeat IHC and sequencing were also performed on a representative tumor block as previously described. If results were still not concordant, the tumor was ultimately classified based on the presence of any pathogenic mutation or abnormal expression pattern (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

RNA extraction and transcriptome analysis

Fourteen MEC cases (10 p53abnl, 4 NSMP) with adequate material and quality metrics were selected for a subset analysis of tumor signaling pathways using the NanoString nCounter® Tumor Signaling 360™ Panel, which allows for profiling of tumor biology, immune evasion, and microenvironment remodeling via expression data of 780 genes. RNA for selected cases was isolated from representative FFPE slides using the Norgen FFPE RNA Purification Kit (Norgen Biotek Corp, Ontario, Canada), according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Samples were processed using the NanoString nCounter® Analysis System (NanoString Technologies, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA). Data analysis was performed using nSolver Advanced Analysis Software and R-project version 4.0.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Raw transcriptome data was normalized using a set of 20 housekeeping genes for each NanoString panel, as per the manufacturer’s Gene Expression Data Analysis Guidelines. Differential gene expression was determined significant if fold change (log2 ratio) was greater than ±1.5, and p value < 0.05. Genes within each panel were pre-classified by NanoString to be associated with certain signaling pathways or biologic functions. T-tests were utilized to compare differences in gene expression of these “themes” among molecular classes.

Statistical analysis

Demographic, clinicopathologic factors, and treatment outcomes were compared between patients based on molecular class. Categorical variables were compared using X2 and student’s t-tests, and continuous variables were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from surgery until disease recurrence or death. A Cox proportional hazards model was utilized to perform a multivariable regression analysis, and hazard ratios were used to evaluate risk factors associated with PFS. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to compare PFS based on molecular class, histology, and HER2 score, and survival differences were estimated using the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP software version 17 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989-2023).

Responses