A service evaluation following the implementation of computer guided consultation software to support primary care reviews for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) represents a common source of morbidity, mortality and healthcare utilisation worldwide1,2. To improve patient outcomes and to address healthcare inequality in COPD, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) and other organisations regularly produce and update clinical guidelines that are easily accessible to healthcare professionals3,4. Despite the publication and dissemination of such guidance, data from UK studies show that over time there remains a lack of adherence to guideline-based practice in terms of implementing the recommendations contained in such guidelines resulting in challenges within all areas of COPD management such as reaching an accurate diagnosis of COPD, recognition of comorbidity, medicines optimisation, under-referral to pulmonary rehabilitation and smoking cessation5,6,7,8,9,10,11. It is evident that simply disseminating guidelines to healthcare professionals with the hope that they will be followed, as has been done for many years, is unlikely to change the status quo and the focus should lie in solutions that are scalable, intuitive and importantly, can demonstrate strong evidenced-based outcomes in widely disparate populations. A digital solution that may help to address the issues highlighted above is the development of clinical decision support software systems. We have previously reported that the utilisation of Computer-Guided Consultation (CGC) software when performing COPD and asthma reviews within primary care demonstrated is not only feasible but also improves diagnostic accuracy and ensures that significantly more patients with a diagnosis of COPD and asthma receive care that is consistent with clinical guidelines12,13.

However, there remains the question as to whether such findings are reproducible when such technology is implemented on a wider scale nationally particularly when it is integrated into a bespoke clinical pathway. Furthermore, when taking COPD management in primary care, beyond this feasibility study, little is known regarding the effectiveness of such technology in improving referral rates to pulmonary rehabilitation and smoking cessation as well as aiding identification of possible significant comorbidity frequently known to complicate COPD such as cardiac disease and bronchiectasis3,12. In this study, we report on the outcome of the previously validated COPD clinical decision support software when performing COPD reviews in 254 GP practices within NHS England.

Materials and methods

The lunghealth COPD computer-guided consultation

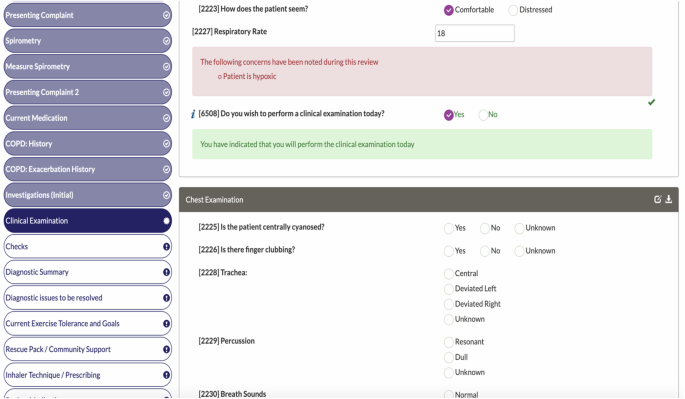

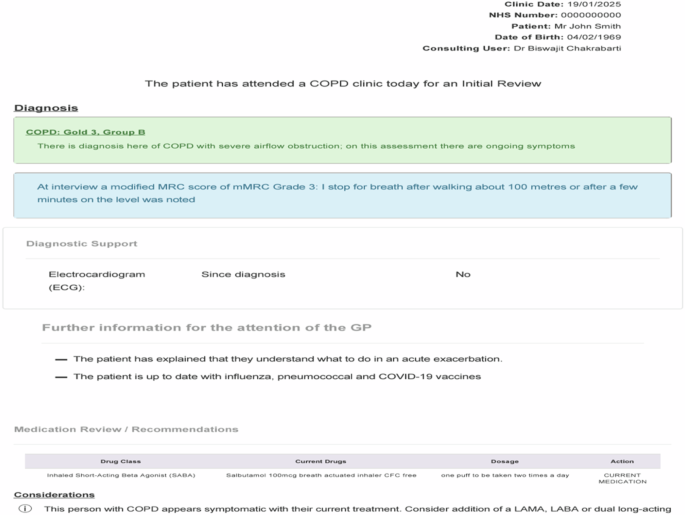

The Computer-guided consultation (CGC; LungHealth Ltd©) is an intelligent structured electronic COPD consultation which can be used to review patients either face-to-face or remotely utilising video technology with key functionality elements outlined in Table 112. Unlike standardised electronic templates and commonly used clinical decision support software, the CGC acts as a “sat nav” directing the operator from symptoms to diagnosis and then onto management. The CGC collects a purposeful history to support a diagnosis of COPD integrating key symptoms, history and examination findings in an intelligent fashion along with interpretation of spirometry and consideration of appropriate investigations generating both pharmacological and non-pharmacological management recommendations (see Fig. 1, 2). The CGC is hosted on a local UK NHS server and has two-way connectivity with the primary care server. At the beginning of each consultation the patients is invited to take part and gave consent to the use of the system, to their records being held electronically and their data being used anonymously for reports. The system is password protected enabling Caldicott principles and General Data Protection Regulations to be satisfied thus ensuring patient data gathered during consultations is duly and lawfully protected and that these data are only used when it is appropriate to do so, with anonymity being preserved14.

“Clinical Examination” screen of the Clinical Guided Consultation (“test patient” review).

Patient Summary Report in the Clinical Guided Consultation (“test patient” review).

The pathway evaluation

This quality improvement project involved 254 GP surgeries across England and Wales.

Study design

Phase 1a: Patients on the COPD register (i.e. having a READ code diagnosis of COPD) within each GP practice were identified using a bespoke MIQUEST (Morbidity Query Information Export SynTax)©/SNOMED (Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms)© Software tool.

Phase 1b: Each patient identified on the COPD register then underwent a case note review conducted by the lead service GP together with a trained primary care respiratory specialist nurse from National Services for Health Improvement Ltd. Prior to the commencement of Phase 2, the GP also completed a Practice Treatment Protocol with the Primary Care Nurse specialist for COPD patients in the practice, ensuring all management interventions were in line with both GOLD guidance and local policy3.

Phase 2: Patients were invited for a clinical review using the CGC conducted by trained primary care respiratory specialist nurses from National Services for Health Improvement Ltd.

Phase 3: Following completion of the CGC reviews, each GP practice received a COPD education and training session (using Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) accredited modules) conducted by the primary care respiratory specialist nurse following the reviews.

All patients gave individual consent to be reviewed using this CGC and to the holding of their data, including pooled anonymous data to be used for reports and research. These reviews were conducted in a face-to-face or remote manner. If it was not possible for spirometry to be performed as part of the consultation, prior spirometry was inputted into the CGC by the operator. In either scenario, only those spirometry traces and recordings which met guideline standards following visual inspection by the operator were entered in the CGC15.

The final analysis was performed taking only those patients undergoing CGC review who had valid spirometry entered as part of the consultation.

Study outcomes

-

The role of the CGC in improving diagnostic accuracy of COPD: The study aimed to define the proportion of patients who had been misdiagnosed with COPD yet were on the primary care COPD register.

-

The role of the CGC in improving the detection of potentially significant comorbidity: The study aimed to define the proportion of patients which the CGC flagged as warranting investigation for potential underlying cardiac disease, bronchiectasis and a disproportionate degree of hypoxia.

-

The role of the CGC in improving key areas of non-pharmacological management of COPD: The study aimed to define the proportion of patients which the CGC deemed as appropriate for pulmonary rehabilitation referral, smoking cessation counselling and referral, creation/modification of self-management plans and eligibility for vaccination.

-

The role of the CGC in improving key areas of pharmacological management of COPD: The study aimed to ensure that patients were administered pharmacotherapy that was aligned with COPD staging and with clinical guidelines.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were involved in the initial design and subsequent refinement of the CGC. We carefully assessed the burden of the trial interventions on patients. We intend to report this service evaluation to patients and will actively seek patient and public involvement in further shaping the clinical pathway resulting from this service evaluation.

Ethical approval

Formal ethical approval to conduct the analysis was obtained from the Health Research Authority (REC reference24:/NW/0155).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 28.0. Data are presented as mean±SD unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05. The independent sample t-test was used to identify significant differences in continuous variables and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. The McNemar’s test was used to determine significant differences on a dichotomous dependent variable between paired data.

Results

5221 patients on the COPD register in 254 GP practices underwent a respiratory therapy review using the CGC between March 2021 and March 2023. Spirometry had been performed prior to the CGC review in all but 5 cases where it was performed during the consultation itself. In all cases where historic spirometry had been entered into the CGC, the spirometry had been performed since the patient had been entered onto the COPD register.

The role of the CGC improving diagnostic accuracy of COPD

Overall, 21.1% (n = 1104; mean age 71 (SD 11) years; 52% Female) of the identified COPD population were found not to have COPD according to GOLD guidelines based on spirometry. This was highlighted by the CGC in all cases and the healthcare professional alerted accordingly (McNemar’s test; p < 0.001). Table 2 presents the lung function results of patients on the COPD register without a COPD diagnosis. 13% (681 patients) had spirometry results within normal limits whilst 10% (404 patients) were identified by the CGC as having restrictive lung function. A further 19 patients were highlighted by the CGC as having asthma based on post bronchodilator reversibility of 400mls or greater.

Patients who were found not to have a diagnosis of COPD based on spirometry criteria were significantly younger (71 v 74 years; t = 8.66; p < 0.0001) and more likely to be female (52% v 46%; chi-square = 14.3014; p = 0002) when compared to those with a diagnosis of COPD.

The number of patients diagnosed with COPD through spirometry based on GOLD criteria was 4117. These patients underwent consultations using the CGC tool, of which 47% (1950/4117) were conducted face to face. Table 3 provides details about key demographics obtained through the CGC review.

The role of the CGC result in improving the detection of potentially significant comorbidity

When taking those 4117 patients with an established diagnosis of COPD following CGC review, in 7% (303 cases), the software highlighted key findings of new onset cardiac disease that had not previously been recognised by healthcare professionals and which was deemed significant enough to warrant further investigation (CGC alerted the healthcare professional in the form of “Cardiac Alerts”). In 290 of these cases, this was due to the software detecting symptoms and signs indicative of new onset cardiac failure with the software prompting further assessment and investigation. In 13 cases, this was due to uncontrolled hypertension specifically needing medical review i.e. systolic blood pressure of 180 mmHg or greater.

In the entire cohort, use of the CGC software identified 2.1% (88 patients) who had an established concomitant diagnosis of bronchiectasis at the time of review. The CGC review reported a history of chronic cough present on most days, productive of an eggcup (50 ml) or cupful (250 ml) of purulent sputum on a near daily basis in 134 patients (3.4%; 106 reporting an egg-cupful purulent sputum daily and 28 reporting a cupful of purulent sputum daily) with only 13 (10%) already having an established diagnosis of bronchiectasis. The CGC prompted consideration of this diagnosis in the remainder of this group.

The presence of low oxygen saturation (i.e.<=92%) on room air was noted in 0.02% (74 patients) which was highlighted in all cases to the healthcare professional along with the need to consider specialist review and/or oxygen clinic referral dependent on other features of the CGC review. Of these patients, 46% (34/74) were noted to have hypoxia but with an FEV1> = 50% predicted. Here, the CGC additionally highlighted to the healthcare professional the need for further specialist referral to determine alternative or coexisting aetiologies. The CGC noted that 6% (n = 254) of the cohort reported that they had never smoked with an additional 16% (n = 685) reporting that they had smoked 10 pack years or less. In all these cases, the CGC highlighted this to the healthcare professional recommending consideration of further investigation and assessment as to the aetiology of the patient’s diagnosis.

The role of the CGC in improving key areas of non-pharmacological management of COPD

38% (1564/4117) did not have a written COPD management plan prior to CGC review. 60% (943/1564) of those patients not possessing a written COPD management plan had a plan created with the healthcare professional during the CGC review itself and issued to the patient following the consultation. The remainder were scheduled at a future date. Thus, by the end of the CGC review, the number possessing a written management plan rose from 62% (2553/4117) to 85% (3496/4117; McNemar’s test; p < 0.001). Where the patient already had a COPD written management plan in place prior to the CGC consultation, the healthcare professional felt that the management plan needed to be revised in 10% of cases (n = 254).

28% (1158/4117) were current smokers and in every case, the software prompted the operator to counsel the patient regarding tobacco consumption together with offering referral to smoking cessation services. During the CGC review, 99% (1142/1158) of current smokers were counselled regarding smoking cessation by the healthcare professional with the CGC displaying smoking cessation educational prompts to the user. 13% (554/4117) were found to have suboptimal inhaler technique with the software prompting correction of deficient technique in all cases. The healthcare professional documented that the suboptimal technique had been addressed in 264 (48%) of cases during the consultation itself, with the remainder scheduled for further consultation to address this.

CGC reviews highlighted that 1996 patients were eligible to be referred to pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) according to guidelines, and in each case, the software prompted the healthcare professional to consider triggering referral for PR according to local policy (the timing of any previous PR programs completed was considered). Only 26% (n = 527) of the cohort deemed eligible for PR had previously attended a PR program. In 308 patients deemed suitable for PR referral (15% of those deemed eligible by the CGC according to guidelines), the healthcare professional noted a specific medical contraindication to PR that had been highlighted by the CGC educational prompts.

CGC review found that 11% (n = 446) and 10% (n = 394) of patients had not been up to date with Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccination respectively with the software prompting the healthcare professional to offer these interventions to the patient.

The role of the CGC in improving key areas of pharmacological management of COPD

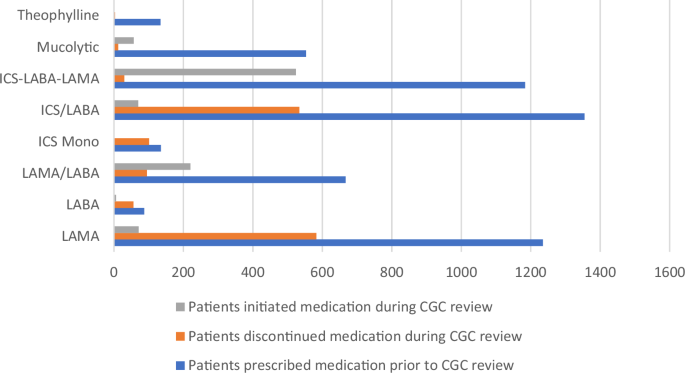

Fig. 3 outlines the proportion of patients prescribed common classes of medication for COPD at the time of performing the LungHealth CGC in addition to those where such medications were discontinued or commenced following the LungHealth CGC. All changes made followed recommendations in keeping with GOLD standards according to patients’ symptoms and exacerbation history.

COPD medication changes resulting from CGC review.

2674 patients were prescribed inhaled corticosteroid preparations prior to CGC review of whom 5% (135 patients) had been prescribed ICS monotherapy. Of those 135 patients, ICS monotherapy was discontinued in 75% (101/135) of whom 25 were commenced on ICS/LABA therapy, 30 were commenced on ICS/LABA/LAMA (“Triple” therapy), and 46 were prescribed bronchodilators only. In the remaining cases, the ICS therapy was continued after a detailed clinical review and taking into account patient preference.

Nine patients were changed from ICS/LABA/LAMA (“Triple” therapy) to LABA/LAMA therapy and 45 patients were switched from ICS/LABA therapy to LABA/LAMA therapy. 220 patients were escalated to combined LABA/LAMA bronchodilator therapy following CGC review. Of these, 34 were switched from LABA monotherapy to LABA/LAMA therapy and a further 151 patients switched from LAMA monotherapy to a LABA/LAMA therapy. 524 patients were commenced on ICS/LABA/LAMA following CGC review of whom 74 patients were escalated from LABA/LAMA therapy and 407 patients were switched from an ICS/LABA inhaler. Thus, the proportion who had been prescribed ICS/LABA/LAMA rose from 29% (1184/4117) prior to CGC review to 41% (1678/4117) following CGC review.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the implementation of a clinical pathway involving the use of clinical guided consultation when performing primary care COPD reviews results in a significant reduction in the misdiagnosis of COPD, an increase in the detection of possible serious comorbidity complicating COPD as well as an increase in the uptake of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological management that is aligned to recognised guidelines.

An increasing number of complex clinical guidelines are disseminated to healthcare professionals based in primary care16. Our study has demonstrated that guideline-level practice is often not followed in COPD care and furthermore, the use of clinical decision support software technology such as the CGC leads to greater implementation of guideline level care which reduces variation in the standard of care thus addressing health inequality. The scalability of the clinical decision support system and on a wider level, the clinical pathway is supported by the fact that the identification of appropriate patients using the MIQUEST and SNOMED tools and the subsequent CGC reviews may be performed remotely offering read and write back to the GP clinical record and with the pathway being utilised in 254 GP practices nationally.

The consequences of an incorrect diagnosis of COPD may include failure to recognise the true aetiology of the patient’s symptoms such as cardiac disease as well as the potential adverse effects of pharmacological overtreatment and altered survival9,17,18,19,20,21,22. One reason cited as a cause of COPD misdiagnosis has been the lack of access to high-quality spirometry, and this issue has recently been worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic23,24. However, consistent with the literature, our analysis shows that even when such spirometry has been performed in a patient to guideline standard, the appropriate interpretation of this investigation and correlation with key clinical findings, principles of which are integral to correctly diagnosing any condition including COPD, are often absent25,26. The CGC intelligently interpreted spirometry tests through it’s programmed algorithms to established guidelines and alerted the operator that 13 and 10% of patients on these primary care COPD registers had normal and restrictive spirometry respectively. These patients were relieved of an incorrect diagnosis and further medical review was prompted to seek alternative causes for their symptoms such as previously undiagnosed cardiac disease. The incidence of overdiagnosis reported in our analysis demonstrates that despite the dissemination of clinical guidelines year after year, the messages focusing on the need for robust diagnosis in COPD contained in such guidelines remains hard to achieve27. A study of 1044 patients with a label of COPD referred for pulmonary rehabilitation between 2007 and 2010 revealed a misdiagnosis rate of 20% based on spirometry criteria and also similar to our findings, men were more likely than women to be accurately diagnosed28, In another analysis of over 14,000 COPD patients in primary care in 2013, consistent with our report, 13.1% had no recorded spirometry and that where spirometry was performed, 11.5% had no evidence of airflow obstruction21. We would thus conclude that in clinical practice, the key to achieving a robust diagnosis of COPD however lies beyond simply the interpretation of valid spirometry but in the integration of lung function with a structured clinical assessment, a process aided by the CGC in this analysis. The use of the CGC may therefore support the re-integration of Spirometry back within primary care. An additional utility of such software lies in the setting of newly created “Diagnostic centres” where it may enhance the accuracy and quality of the diagnostic process for those patients with respiratory symptoms who are suspected of having COPD. Those patients in whom the spirometry does not support this diagnosis could then be directly referred for further assessment including cardiac investigations. Further studies evaluating the validity of such a pathway are needed.

Clinical guidelines in COPD emphasise the importance of recognising and treating comorbidity3. The presence of coexisting heart failure is common in COPD yet often remains undiagnosed despite it being an independent predictor of all-cause mortality, whilst uncontrolled hypertension is associated with an increased rate of hospitalisation with the presence of coexisting cardiovascular disease in COPD also being a driver of increased healthcare costs29,30,31,32. The use of the CGC in COPD reviews highlighted new findings suggestive of significant cardiac disease in 7% of patients and prompted the healthcare professional to consider referral for further investigation. The intelligent software was also able to highlight cases of uncontrolled hypertension. Outside the cardiovascular system, co-existing bronchiectasis in COPD is associated with frequent exacerbations, worsening lung function and increased mortality3,33. The GOLD guidelines reference the production of large volumes of purulent sputum as suggestive features of bronchiectasis and the CGC review determined that of all patients with airflow obstruction reporting this symptom, only 10% had previously been diagnosed with bronchiectasis and prompting consideration of this possibility in the remaining 90%3. Further longitudinal studies are needed to determine the outcome of those patients referred for further investigations of suspected comorbidity following CGC review and particularly when compared to “usual care” and whether the application of machine learning to such software systems may further enhance the ability of healthcare professionals to diagnose comorbidity promptly in such scenarios.

The appropriate and timely referral to specialist services is another key component of guideline-based practice. The incorporation of pulse oximetry when performing COPD reviews in primary care allows primary care practitioners to refer patients for consideration of Long-Term Oxygen Therapy34. In addition to CGC identifying those suitable for domiciliary oxygen, in 46% of patients with hypoxia, the CGC highlighted that this could be disproportionate to the degree of lung function impairment further illustrating the role of such technology in aiding diagnostic certainty, improving patient safety whilst simultaneously upskilling healthcare professionals. COPD guidelines also recognise the importance of healthcare professionals delivering smoking cessation advice to their patients during each review yet this is frequently not performed3,35,36,37,38,39,40. The use of the CGC resulted in 99% of patients who smoked receiving smoking cessation counselling and brief intervention during the consultation with the recommendations to refer on for further support if the patient was willing. Furthermore, the database underpinning the CGC captures the “smoking status” of a patient in consultations longitudinally allowing stakeholders accurately to measure the effectiveness of key interventions and also accordingly tailor the nature of local smoking cessation services.

The introduction of structured self-management programmes and written action plans in COPD conveys clinical benefit including a reduction in hospital admissions, improved health related quality of life and a favourable health economic profile and is recommended as guideline standard care3,41,42,43,44,45. The CGC review resulted in a significant increase in the provision of written action plans to include 85% of the cohort. Similarly, guidelines emphasise the importance of correct inhaler technique and the need to check inhaler technique regularly in COPD. Critical errors in inhaler technique are associated with an increased frequency of exacerbations which impacts not only the patients but also health economics46. The CGC reported that 13% of patients had sub-optimal inhaler technique although the fact that this could only be addressed in just under half of cases during the consultation may reflect the fact that remote reviews constituted a significant proportion of the consultations. The Covid-19 pandemic resulted in an increase in the proportion of those patients undergoing remote reviews and more detailed studies are required to fully understand the effectiveness of remote reviews (through video and telephone) in chronic respiratory conditions such as COPD when compared to traditional face to face consultations and whether the use of clinical decision support systems may improve outcomes in specific areas of COPD management when undertaking remote consultations.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) also represents an important guideline standard intervention in COPD which is often underutilised3,47. In an Australian study, referral for PR was described as the least well implemented guideline intervention in COPD and an important barrier for PR referral was low awareness of the program by healthcare professionals, with key recommendations being the identification of suitable patients and streamlining the referral process47. This is supported in our analysis as only 26% of patients who the CGC had identified as being eligible for PR had previously attended a PR program. The use of a clinical decision support system as described here may overcome such barriers by intelligently identifying those patients who are suitable according to guideline standards and subsequently prompting the operator to consider PR referral during the consultation as well as simultaneously upskilling the operator through educational prompts outlining the medical contraindications to PR referral. Thus, an additional utility of technology such as the CGC lies in its incorporation into a clinical pathway that aims to optimise the PR referral process by ensuring all patients referred initially undergo CGC review to ensure correct diagnosis, undergo detailed assessment of significant comorbidity and receive structured holistic self-management.

Whilst the use of inhaled corticosteroid-bronchodilator combination therapy represents evidence-based practice for selected COPD patients with exacerbations, guidelines now also recommend considering de-escalation of such therapy where appropriate. The use of inhaled corticosteroid monotherapy does not constitute guideline-based practice and over-prescription of inhaled corticosteroids and lack of appropriate withdrawal when no benefit exposes patients to adverse effects and negatively impact on health economics3,18,48, In addition to prompting escalation of therapy as per guideline recommendations, CGC review resulted in the discontinuation of inhaled steroid monotherapy in 75% of cases where patients had been prescribed these on entry to the software. The confidence of clinicians to de-escalate medication in any given condition such as COPD is incredibly important yet often overlooked and may further be strengthened by the application of technology such as the CGC enabling accurate diagnosis, staging and management of that condition49. Further qualitative research is needed in this specific area of practice.

A key strength of this evaluation lies in it’s large sample size spread across a wide catchment area and that every patient on the register was reviewed using a structured clinical pathway where on entry, the diagnosis of COPD was either confirmed or refuted based on spirometry using a clinically validated digitally accredited tool. Furthermore, patients with a confirmed diagnosis were appropriately staged in terms of disease severity at this Initial Review consultation. This diagnostic screening process ensured the accuracy and validity of any subsequent guideline standard pharmacological and non-pharmacological recommendations generated from the remainder of the CGC review. One limitation is that the CGC reviews consisted of a mixture of face-to-face and remote consultations (driven in part by the Covid-19 pandemic) which could have affected the delivery of some of the guideline level interventions described. Whilst the consultations described were all performed by trained primary care respiratory specialist nurses, the interventions detailed here represent those driven or primarily prompted by the CGC which a practice nurse conducting a COPD review could have followed. Community spirometry services were also affected by the Covid-19 pandemic which, in this analysis, limited those undertaking the consultations from performing spirometry during the consultation itself. This paper reports on interventions prompted by the CGC in a cross-sectional analysis and whilst the CGC reviews greatly increased the proportion of patients managed within guideline-based recommendations, it is hoped that this will result in an improvement in health-related quality of life for patients and a reduction in exacerbations, healthcare utilisation and hospitalisations in the future. However, the clinical guidelines themselves detail interventions demonstrated to reduce healthcare utilisation and improve health-related quality of life in COPD thus it is not unreasonable to extrapolate that any clinical pathway increasing uptake of these guidelines would achieve the same effect although this does require further prospective study. Finally, whilst preliminary data exists detailing the health economic benefits of the CGC during initial feasibility studies, further analysis is required to define the such benefits realised by utilising this specific clinical pathway as a result of increased clinical guideline implementation.

Conclusion

When performing COPD reviews within primary care, the appropriate utilisation of technology in the form of a clinical decision support system software technology integrated within the clinical pathway as outlined here leads to greater implementation of guideline-level care and furthermore, represents a scalable solution when performing COPD reviews within primary care.

Responses