The effect of allergic rhinitis treatment on asthma control: a systematic review

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that reported one or more objective or subjective asthma outcome and compared the efficacy of anti-AR medication to placebo or conventional asthma medication (see outcome measures below) were included. Open-label, single-blind and double-blind trials were included.

Studies with children and/or adults were included. Participants needed to be diagnosed with asthma and AR. Studies were only included if asthma was defined using more than one of the following criteria: clinician-diagnosed asthma; at least one clinical respiratory symptom (wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, cough, reversibility of forced expiratory volume (FEV1) > 12% in spirometry); the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS); or the use of bronchodilators for at least six weeks a year because of asthma symptoms.

Rhinitis was limited to AR. AR diagnosis was based on clinical criteria and a positive skin prick test or radioallergosorbent (RAST) test. Clinical criteria consisted of sneezing, runny nose, itching, rhinorrhoea and/or nasal congestion. Only studies that examined patients with both asthma and AR were included; studies in which subjects had allergic asthma or atopic disease were excluded.

The interventions considered were: anti-AR medication compared to a placebo, to other conventional asthma medication or adding anti-AR medication to other conventional asthma medication.

Conventional anti-allergy medication included INCS, AH, decongestants and local cromoglycic acid. Conventional asthma medication was defined as: corticosteroids (inhaled, oral or intranasal), short and long acting β2 agonists and LRA.

Studies examining allergy immune therapy and biologics were excluded as these therapies are recommended for specialist treatment of severe AR and less so in general practice16,17. Nonconventional treatment options, such as acupuncture, homeopathic therapy and aromatherapy were excluded. There were no limitations to the study setting (primary care or hospital care). In- and exclusion criteria are summarised in Table 1.

Outcome measures

The analysed subjective asthma-related outcome measures were: nocturnal and daytime symptom scores18,19 and QOL assessment scores (RHINASTHMA, adult quality of life questionnaire (AQLQ), pediatric quality of life questionnaire (PAQLQ), Juniper mini asthma QOL20,21,22). Objective outcome measures were airway calibre markers (FEV1, PEFR – Peak Expiratory Flow Rate), escape short acting beta-2-agonist (SABA) use and inflammatory markers (provocation concentration(PC)20/provocation dose(PD)20, exhaled nitric oxide (NO)). If available, the Minimal Clinical Important Difference (MCID) was added to interpret the clinical relevance of changes in outcomes.

Search methods

The Embase, Medline and Cochrane central databases were searched with the assistance of an information specialist. The main search terms were: (asthma OR wheezing OR hyperresponsiveness OR hypersensitivity) AND (rhinitis OR conjunctivitis OR rhinoconjunctivitis OR hayfever) AND (‘antiallergic agent’ OR ‘decongestive agent’). The complete search string can be found in supplementary method I.

All articles were screened for inclusion, regardless of publication date or language. The last search was performed on 24-09-2024.

Data collection and analysis

Titles and abstracts resulting from the electronic search were screened by two reviewers (ET, AB), following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines23. Disagreement between the reviewers was resolved by a third reviewer (GE). Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (ET), using a predefined form listing the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above. If available, absolute values were preferred to relative changes compared to baseline. If possible, data were extracted from graphical plots. In case of intermediate measurements, only results from the primary endpoints were considered.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The quality of the included articles was assessed (ET, AB) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool for randomized trials. This tool assesses a fixed set of domains for potential bias, including trial design, conduct and reporting. Using signalling questions for each domain, the tool proposes an assessment of the risk of bias. Both the tool and the reviewer can assess the risk of bias to be ‘low’ or ‘high’, or can express ‘some concerns’. Articles with high risk of bias were excluded.

The protocol of this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO.

Results

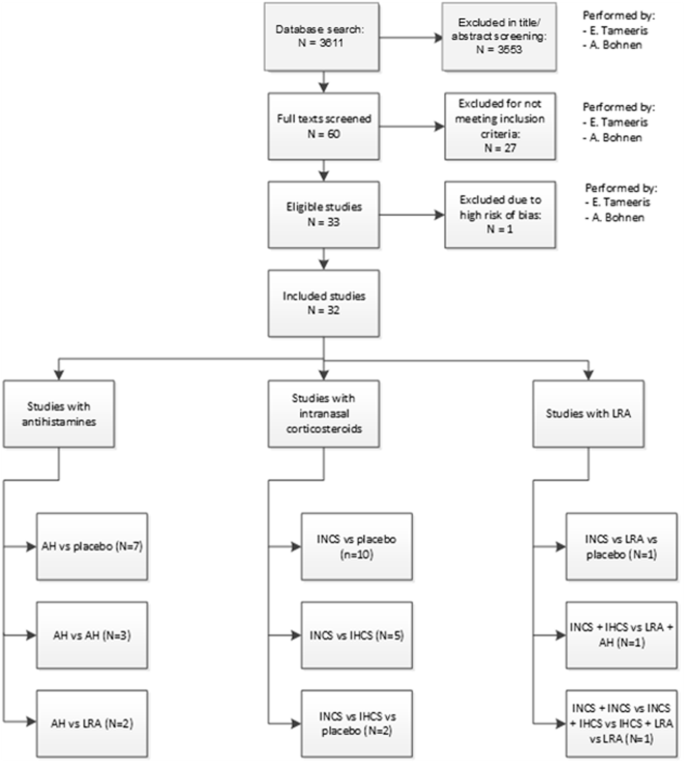

The search was performed and updated up to October 2024. In total, 3762 unique publications were retrieved. After title and abstract screening, 60 articles remained for full-text assessment. 33 articles were included in this review. One article was assessed as high risk of bias and was excluded. The primary reasons for exclusion in the full-text assessment were: no asthma diagnosis (n = 7), no conventional medication studied (n = 7), no AR diagnosis (n = 4) (Fig. 1).

Flowchart of the inclusion process.

The included studies were published between 1988 and 2018. Seven studies compared AH to placebo24,25,26,27,28,29,30, of which one used intranasal AH27. Ten compared INCS to placebo31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Three studies compared AH41,42,43 and two AH in addition to LRA44,45. Five studies compared INCS to IHCS46,47,48,49,50 and two studies INCS to IHCS and placebo51,52. The use of INCS was compared to LRA and placebo in one study53 and another study compared combined INCS and IHCS with LRA and AH54. One study compared the use of INCS alone with a combination of INCS and IHCS, a combination of INCS and LRA, and LRA alone55. The study investigating intranasal AH reported no statistically significant outcomes27.

Of the 32 studies included in this review, three had a crossover design34,47,54. The number of included patients varied from 12 to 1385. In total, 5987 patients were studied. Six studies had a paediatric study population (participants <18 years old)26,34,37,39,43,46 and the population of 16 studies was partly paediatric28,29,30,31,32,35,41,44,45,48,49,51,52,53,54,55. Of the 33 studies, 16 performed measurements during the pollen season24,27,28,29,30,32,33,35,36,41,42,44,45,50,51,52. The intervention time in the reviewed studies varied from two to 26 weeks. Outcome measures are reported in Tables 2–4. An overview of the clinical symptom scoring methods used in the reviewed studies can be found in Supplementary Table 8.

Subjective asthma outcomes

Subjective asthma outcomes were reported in 29 studies24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,51,52,53,54,55,56. Most studies used an asthma symptom scoring system, allowing patients to log symptoms in a diary on a point scale (most commonly 0–3 points per symptom; see supplementary table 1 for specifications of the scoring systems).

Antihistamines

Of the studies investigating AH, 11 reported asthma symptom scores (ASS)24,25,27,28,29,30,41,42,43,44,45,57. Nine studies found a significant improvement, the clinical relevance of these improvements is not described. There are no differences in outcomes between studies performed during the pollen season24,27,28,29,30,41,42,44 and those performed outside the pollen season45. Tinkelman et al. (1996) performed their study on an exclusively paediatric population43. Nathan (2006), Pasquali (2006) and Balzano (1992) had an exclusively adult study population. No differences were seen in the subjective asthma symptoms for the different study populations. Nathan (2006) measured the QoL with the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ), which resulted in a significant improvement from 4.4 to 3.5. The minimal important within-subject change in the AQLQ overall score is 0.5, and the reported improvement is considered moderate21,24. Pasquali (2006) measured the RHINASTHMA global summary (GS) score, which improved from 28 to 16 in the levocetirizine intervention group, versus an improvement from 31 to 27 in the placebo group25.

Intranasal corticosteroids

Fourteen studies described the effect of INCS on reported ASS31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,46,48,49,51,52. In seven studies, a statistically significant improvement in asthma symptoms was found (see Tables 2, 3). There were no differences seen in the overall study outcomes or any effect depending on whether they were measured during32,33,35,51,52 or outside the pollen season31,34,36,39,40,48,50. Results did not differ between studies with a mixed age study population, studies that had an exclusively paediatric study population34,39,46 and those with an exclusively adult study population33,36,40.

Scichilone (2011) and Baiardini (2011) described a significant improvement in the RHINASTHMA GS score (0–100 scale). Both intervention groups in the study of Scichilone (2011) remained above the 20-point score, indicating suboptimal health-related QoL. Baiardini (2011) reported an improvement from baseline of 10.36 (SD 1.98) points in the intervention group. Nair (2010) found a significant but not clinically relevant improvement in the Juniper mini asthma QoL questionnaire. The QoL improved from 5.91 (0.20) to 6.22 (0.14) in the low dose group, the combined dose group QoL improved from 5.78 (0.18) to 6.11 (0.11) and the QoL in the high dose group improved from 5.82 (0.21) to 6.07 (0.20) (minimal clinically important difference (MCID) 0.5). Kersten (2012) measured QoL using the Paediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ). A non-significant improvement from 6.0 to 6.2 was seen in the treatment group. The MCID for the PAQLQ is 0.558.

Leukotriene receptor agonists

Three articles investigated the effect of LRAs on asthma symptoms53,54,55. In the study by Barnes et al. (2007), a significant improvement was only seen in the combined topical steroid therapy arm, not in the combined mediator antagonist arm. The clinical relevance of the improvement is uncertain54. The percentage of symptom-free days improved significantly in the studies of Nathan (2005) and Katial (2010). Nathan (2005) reported improvements from 5.3% (1.0) to 20.6% (3.3) in the topical steroid intervention group, significantly greater than the 6.8% (1.0) to 23.4% (3.2) and 6.1% (1.0) to 23.6% (3.3) improvements in the LRA and placebo arms. Katial (2010) reported an improvement from 3.5% (0.6) to 33.4% (2.1) and from 3.3% (0.6) to 32.7% (2.1) in the combined treatment arms. The isolated inhaled steroid arm improved from 4.2% (0.7) to 33.6% (2.1) and the LRA intervention arm improved from 3.7% (0.6) to 20.3% (1.9). In these studies, the treatment arms with INCS (with or without IHCS) performed significantly better than the arms with LRA. The three studies were all performed with a partially paediatric study population.

Objective asthma outcomes

The objective asthma outcomes analysed were FEV1 (% predicted), PEFR and use of escape medication (SABA). Twenty-five articles reported outcomes regarding FEV1, 19 studies reported on PEFR, and 14 studies examined the beta-agonist use in their study populations. The MCID for FEV1 is 0.23 L or 10.4% change from baseline in adults59. This was seen in the study by Camargos (2007), comparing INCS to IHCS46. A clinically relevant and statistically significant change from baseline in PEFR (18.8 L/minute or 5.39%) was seen in the studies of Corren (1997), Nair (2010), Nathan (2005) and Katial (2010)30,47,53,55.

Antihistamines

Eight studies regarding AH reported FEV1 outcomes24,26,29,30,41,42,44,45. A significant improvement in FEV1 for the intervention groups compared to the placebo was seen in the studies of Corren (1997) and Baena-Cagnani (2003)30,44. None of the improvements in FEV1 met the MCID of 0.23 L or 10.4% change from baseline (10% for paediatric patients)60. PEF only improved significantly and clinically relevant (intervention group) in the RCT by Corren (1997) (baseline +21 L/min; +10 L/min for the loratadine and placebo groups, respectively)30. Segal (2003) conducted their study on an exclusively paediatric study population. No differences were seen in the outcomes compared to the other studies, where both paediatric and adult subjects were studied (Table 5).

Intranasal corticosteroids

FEV1 changes were reported in 15 RCTs that compared the effect of steroids31,33,35,36,37,39,40,47,48,49,50,51,52. Most studies reported no significant change in FEV131,33,35,36,39,40,49,52 and others showed non-clinically relevant improvements35,47,48,51. A statistically significant and clinically relevant improvement in FEV1 was seen in both the INCS and IHCS intervention arms of the study by Camargos (2007) ( + 12.30% pred; + 10.25% pred)46. PEF improved significantly in the high-dose (fluticasone propionate 250 ug (IH) + placebo (IH) 2dd + placebo (IN) 1dd) and combined dose (fluticasone propionate 50ug (IH) + placebo (IH) 2dd + fluticasone propionate 100 ug/nostril 1dd) intervention groups in the RCT of Nair (2010) (432.02(23.05)-457.35(23.05)L/min, 446.97(23.98)-466.24(24.72)L/min in the combined and high-dose groups, respectively). There is no significant intergroup difference between the treatment arms. In the low-dose (fluticasone propionate 50 ug (IH) + placebo (IN) 2dd + placebo (IN) 1dd) intervention group, a non-significant, non-clinically relevant improvement in PEF was seen47. Dahl (2005) reported significantly better PEF results in the morning PEF of the combined intervention group. The change in PEF was not clinically relevant and the evening PEF did not change significantly. No differences in outcomes were seen between paediatric37,39,46 and adult study populations33,36,40,47,50. The RCTs of Corren (1992), Thio (2000), Dahl (2005) and Scihilone (2011) were performed during the pollen season; their results did not differ from the studies performed outside the pollen season (Table 6).

Leukotriene receptor agonists

In studies regarding LRAs, FEV1 changes did not exceed the MCID54,55. Katial (2010) reported a significant difference in the improvement of FEV1 compared to baseline for the IHCS versus placebo arm, compared to the LRA versus placebo arm. Both studies were performed with a partially paediatric study population. Nathan (2005) and Katial (2010) reported significant improvements in PEF. PEF improvements were clinically relevant in all intervention groups of Nathan (2005)53. Katial (2010) saw a decrease of -5.1(2.4)L/min in the PEF of subjects treated with LRA only (Table 7).

Short-acting beta agonist use

The use of escape SABA changed significantly in four studies. TheSABA reported were albuterol and salbutamol. One reported a significant decrease from 4.75 to 2.35 doses of SABA per week between the intervention (AH) and the placebo41. Dijkman (1990) saw an increase of SABA use from 0.5 to 1.3 puffs per day in the terfenadine control group, whereas the SABA use in the cetirizine intervention group decreased from 0.4 to 0.3 puffs per day41. Comparing AH to LRA, a 12.1–15.9% decrease in use from baseline was seen44. A significant increase in the percentage of albuterol-free days was seen in the study of Katial (2010)55. Outcomes significantly favoured INCS over LRA. There is no MCID described for SABA use.

Inflammatory markers

Changes in airway inflammation were monitored through PD20, PC20 and exhaled FeNO. The provocation dose causing a 20% decline in FEV1 (PD20) and provocation concentration causing a 20% decline in FEV1 (PC20) are measures used to describe outcomes of the highly sensitive metacholine challenge test, provoking an asthmatic reaction in patients. The FeNO test (exhaled nitric oxide test) is a method for determining the amount of lung inflammation present.

PD20/PC20 was measured in 11 studies. Seven studies reported FeNO outcomes. Six studies, comparing INCS + IHCS vs LRA + AH (Barnes, 2007), INCS vs placebo (Corren, 1992; Watson, 1992), INCS vs IHCS (Prieto, 2005; Nair, 2010) and INCS vs IHCS vs placebo (Dahl, 2005), reported a significant improvement in PD20/PC20. Three studies, two comparing INCS vs IHCS (Prieto, 2005; Nair, 2010) and one comparing INCS + IHCS vs LRA + AH (Barnes, 2007) reported significant improvements in FeNO33,34,47,50,51,54. The clinical relevance of these outcomes was not described in the studies. A higher FEV1 (not further specified) and percentage of symptom-free nights was seen in combination with an improvement in mean PD20 by Dahl (2005)51. Nair (2010) reported an improvement in Juniper mini asthma QoL and an improvement in FEV1 (which were not clinically relevant) in combination with significant improvements in PC20 and FeNO47. Both studies compared addition of INCS to IHCS. Barnes (2007), comparing INCS and IHCS to LRA and AH, found a significant improvement only in the corticosteroid treatment arm. The ASS and PEFR improved significantly in this intervention group.

Side effects

The reported adverse effects were mild and did not require hospitalisation. Patients withdrawing from the trials mainly did so due to side effects, (severe) airway infections or asthma exacerbations requiring hospital admission, insufficient AR symptom control, loss to follow-up or noncompliance24,25,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,38,39,40,43,44,45,46,47,49,51,52,53,54,55. Seven studies reported zero withdrawals from their study cohorts26,27,28,37,41,42,50. Six studies had a dropout of >10%45,47,48,49,54,57. Ciprandi (2004) did not report on withdrawals61.

All objective and subjective outcomes per medication group were summarised in Table 8.

Risk of bias in the included studies

In general, the studies had low risk of bias. Any concerns or a high risk of bias were caused by high dropout rates ( > 20%). Most of the studies investigating AH were performed in the 1980s and 1990s. The risk-of-bias assessment did not reveal an extra risk of bias in these relatively old publications, compared to more recent publications. Some studies had a small number of participants (fewer than 20), which increased the risk of bias27,33,52. Aaronson (1996) had a high risk of bias and was therefore excluded57. (Supplementary table 2)

Discussion

Prevalence of both asthma and AR has risen over the past years. Despite these developments, both diseases are still prone to be underdiagnosed, as rates in doctor-diagnosed and self-reported prevalence diverge4,62. Misdiagnosis of airway symptoms leads to flaws in disease management. The most recent ARIA guidelines suggest improving treatment of asthma by optimising the treatment of AR. The guideline describes the influence of AR on asthma, but does not give specific therapeutic recommendations for the combined diseases5. However, in the 2021 update of Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, no advice is given on optimising the AR treatment63. In this review, evidence on the combined treatment of asthma and AR was collected. Patients in the included studies suffered from both asthma and AR. All conventional primary-care treatment options for AR were studied.

ASS were reported in 29 studies. The symptom scoring methods used are heterogeneous, scoring different symptoms and using different scales. This makes it hard to compare outcomes between the studies. Two of these studies used a validated outcome measure for subjective outcomes (Asthma Control Test), which did not have a clinically relevant result45,52. Subjective asthma outcomes improved significantly more often in studies including AH’s than in studies comparing corticosteroids. The studied AHs are all class-II AH, which are considered the treatment of choice in international guidelines. When comparing LRAs to corticosteroids, corticosteroids were superior based on both objective and subjective asthma outcomes.

No differences were seen between RCTs performed during the pollen season and those performed outside, or between studies with a paediatric study population and those without. One of the reviewed studies found a clinically relevant change in FEV1, compared to baseline (Camargos, 2007, comparing fluticasone via face mask to fluticasone via mouth piece)46. A statistically significant but not clinically relevant improvement in both FEV1 and ASS was seen by Baena-Cagnani (2003), Dijkman (1990), Dahl (2005) and Katial (2010)41,44,51,55. A clinically relevant change in PEFR was described in four studies30,47,53,55. There is no MCID described for changes in inflammation markers and use of SABA. In studies comparing corticosteroids to LRA, respondents using corticosteroids performed significantly better on objective outcomes than those using LRA. Significant improvements in rescue beta-agonist use were mostly seen in the studies comparing AH to a placebo or LRA. In the studies comparing corticosteroids to a placebo, no changes were seen in beta-agonist use.

This review is the first review to compare the effects of all available primary-care treatments of AR on asthma outcomes. Studies describing both adult and paediatric populations were included, which makes the results of this review applicable to a wide variety of patients. The results of this review are mainly applicable to general practice. The exclusion of immune therapy, a fast-developing treatment option for both the diseases considered in this review, limits the applicability of this review in specialised secondary care. Since there were no limits on the publication date, a variety of treatment options were included, some of which are not considered standard practice anymore due to side effects (e.g. first generation AHs). Data extraction was performed by one reviewer only. We reduced the risk of errors in the process by using a predefined data extraction tool. By excluding studies investigating immune therapy, this might also have excluded the most recent publications on the treatment of asthma and AR. Studies comparing the conventional anti-AR medication to immune therapy were also excluded. There is a range of outcome measures described in the reviewed studies, especially the subjective asthma outcomes. Due to the variety in measuring instruments for objective asthma outcomes, a meta-analysis could not be performed, as both the data and studied populations were too heterogeneous. In addition, the clinical relevance of the subjective asthma outcomes could not be determined as most researchers used non-validated asthma symptom scoring systems.

In a systematic review of the efficacy of second-generation AHs in patients with both AR and asthma, the authors conclude that AHs provide a steroid sparing effect. The QoL of patients with combined asthma and AR is improved by the use of AHs (versus a placebo). The authors suggest the QoL improves through improvement of ASS. However, these symptom scores did not improve significantly. No changes were seen in pulmonary function64. In the reviewed studies, similar results were found in the AH group. A significant and clinically relevant improvement in QoL was seen, whereas ASS did not show clinically relevant changes.

In a review studying the effect of INCS on asthma control, Taramarcaz et al. found a non-significant improvement in ASS and in FEV1 outcomes. The reviewers recommended continuing the current treatment practice (INCS in addition to intrabronchial corticosteroid) until more research is done14. In the majority of reviewed studies considering steroid treatment for AR, the ASS remained the same. The studies reporting a significant improvement in symptom scores did not see a clinically relevant improvement in these scores. In a meta-analysis comparing the same effects, Lohia et al. found no significant changes in asthma outcomes with the addition of INCS to IHCS. However, in patients that did not yet receive orally inhaled corticosteroids, asthma outcomes did improve from INCS65.

In a recent review, Ferreira et al. recommended a combination of AH, decongestants, bronchodilators and LRA for the treatment of combined AR and asthma syndrome. The biggest role in controlling the chronic inflammatory response is given to corticosteroids. Because of the side effects of these treatment options, the authors consider immunobiological therapy as the treatment of choice66. In the articles studied for this review, no severe side effects were reported.

The ARIA guidelines state that QoL is the most important outcome measure in patients with AR15. The guideline suggests more focus on this outcome in future research. There is no preference for the treatment of seasonal AR with combined oral AH with INCS compared with INCS alone. In perennial AR, INCS alone is preferred. The results of our review support the advice in these guidelines, as the treatment options studied gave similar results.

This review illustrates that anti-AR medication can contribute to better asthma control when treating comorbid asthma and AR. Even though objective asthma outcomes did not change significantly, subjective outcomes such as ASS and QoL showed positive trends. In the reviewed articles, AHs seem to elicit more change in outcomes than the other studied medication groups. LRAs do not seem to influence asthma control. Most of the significant improvements in outcomes found in this review are not clinical relevant and many of the reported subjective outcomes lack standards for clinical relevance. We found no differences in outcomes between studies focussing on adult, paediatric or combined populations. In order to make the outcomes of future research more comparable, the clinical outcomes need to be studied using a limited number of (validated) outcome measuring tools. Following the advice of the recent ARIA guidelines, QoL should be considered one of the primary outcomes. With the emphasis of current research on immune therapy, it is important not to lose sight of primary-care treatment and to make sure this treatment remains evidence-based and up-to-date.

Authors conclusions

Anti-allergic initiated AHs and corticosteroids seemed to have a positive effect on asthma outcomes with AHs having the tendency to elicit more changes in outcomes than the other studied medication groups. LRAs do not seem to influence asthma outcomes. Most significant improvements were seen in QoL and objective outcomes. Future research on the influence of anti-allergic medication on asthma outcome, should emphasis on QoL outcomes.

Responses