Smoking status, symptom significance and healthcare seeking with lung cancer symptoms in the Danish general population

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common and most mortal cancers worldwide1. About two out of three lung cancer patients are diagnosed in an advanced stage, where treatment options and possibility of long-term survival is low1,2,3 hence timely diagnosis of lung cancer is of great importance. Lung cancer screening has been implemented in several countries; however, it has not yet been introduced in Denmark, where a pilot study is currently ongoing to investigate the feasibility of lung cancer screening4,5. Though some cancers will be detected by screening, most cancer must still be diagnosed based on symptoms presented to the general practitioners (GPs). Lung cancer has been categorised as a hard to suspect cancer, among other factors, due to initially vague symptoms6,7,8. When patients present to their GPs with symptoms that might be signs of lung cancer (hereinafter referred to as lung cancer symptoms), GPs may consider the symptoms as alarming and refer for further clinical investigation in a fast-track cancer care pathway9,10. However, only about 40% of individuals experiencing lung cancer symptoms seek healthcare, indicating that the general population may not always perceive these symptoms as significant or potential signs of a serious illness11,12,13.

The public awareness of lung cancer symptoms is lower than awareness of symptoms indicative of other common cancers, such as breast and colorectal cancer14,15. Several triggers and barriers for healthcare seeking exist16,17,18, but overall, individuals are probably more likely to seek medical attention with symptoms they perceive as significant due to e.g. symptom concern or symptom influence on daily activity15. For some, the fear of receiving a serious diagnoses e.g., cancer, may lead to postponement or avoidance of healthcare seeking16. Interpretation of lung cancer symptoms is challenging because symptoms, such as prolonged coughing and shortness of breath, are common and in most cases signs of benign conditions13,19. Likewise, non-specific lung cancer symptoms such as tiredness are frequently reported in the general population and are often unrelated to a specific disease20.

The Danish healthcare system is based on the principles of free and equal access to healthcare. Most diagnostics are initiated in general practice where the GPs act as gatekeepers with opportunity of referring to relevant diagnostic evaluation in e.g., fast-track cancer care pathways, the pulmonologist departments at the hospitals or other secondary healthcare providers21. Only few patients pay for a private consultation outside the public healthcare system.

A history of tobacco smoking is the greatest risk factor for lung cancer1. Further, smoking history is estimated to be the most important factor contributing to social inequality in cancer diagnostics22. Nevertheless, individuals who currently smoke and have recently been diagnosed with lung cancer, have reported that prior to diagnosis, they postponed seeking healthcare regarding their symptoms23. Likewise, studies conducted in both the general population and primary healthcare settings have shown that individuals who currently smoke are less likely to seek care for lung cancer symptoms compared to individuals who never smoked12,13,24. Reasons for this may be, among others, normalisation of the symptoms because they are part of everyday life for many individuals who currently smoke, or related to neglect of the symptoms, possibly triggered by concern or fear of having a smoking-related disease that may be perceived as self-inflicted23,25.

Knowledge about whether lung cancer symptoms are perceived as significant in different groups among the general population, and how symptom significance is associated with healthcare-seeking behaviour is sparse. Improving the understanding of symptom interpretation and implications for healthcare seeking among the general population may improve both social equity and add to the appropriate communication with individuals who smoke, thereby decreasing the risk of diagnostic delay. Thus, this population-based study aims to analyse the associations between smoking status and perceived symptom significance among individuals with lung cancer symptoms in the general population and to investigate the association between symptom significance and healthcare-seeking behaviour with lung cancer symptoms among individuals with different smoking status. In this study, perceived symptom significance is defined as 1) symptom concern and 2) symptom influence on daily activity.

Methods

Study design and population

The present study is a part of a nationwide study, the Danish Symptom Cohort (DaSC). The DaSC was founded in 2012 with a large population-based survey investigating symptom experiences and healthcare-seeking behaviour in the Danish general population. Ten years later a follow-up and expansion, the Danish Symptom Cohort II (DaSC II) was conducted. The DaSC II forms the basis for this study. A total of 100,000 individuals aged 20 years or older, randomly selected from the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS), were invited to participate in a web-based survey. The CRS contains information on all Danish citizens date of birth, gender and unique personal identification number (CRS number)26. Each invitee received an invitation in a public digital mailbox linked to the CRS number. Participation was voluntary and all invitees not wishing to participate could decline either online or by contacting the project group. Non-respondents received a reminder after seven days. This procedure was repeated after additional seven days. Data was collected from May to July 2022.

The questionnaire

The DaSC II questionnaire was developed based on the 2012-questionnaire. The conceptual framework was conducted by scrutinising, adjusting, and eliminating existing constructs and adding new ones. Prior to distribution the questionnaire was qualitative pilot tested twice. First in an academic environment, where 26 participants fulfilled the questionnaire and gave feedback in writing. Subsequent by a user panel consisting of 12 twelve representants of the general population, including both genders and ages (range 20–86 years). The user panel were asked to think aloud while fulfilling the questionnaire and simultaneously being observed by a trained interviewer. Afterwards the interviewer conducted a semi-structured interview based on a pre-prepared interview guide as well as questions elaborating on specific reactions and thoughts while filling in. The quantitative field test was conducted among 499 randomly selected Danish citizens following similar logistics as the final distribution. The pilot and field tests resulted in minor rewordings of the questions, reduction of questions and some clarifications throughout the questionnaire. The methodological framework, including details on the development, pilot testing, and field testing, is described in detail elsewhere27.

The questionnaire comprised 44 symptoms, including both specific and non-specific cancer symptoms as well as frequent symptoms. Participants were asked to tick of symptoms they had experienced within the preceding four weeks. For each reported symptom, additional questions about symptom onset, healthcare-seeking behaviour (e.g., GP contact, physical therapist, see Supplementary materials, Table S1), concern about the symptom and the symptom influence on daily activities were asked. Further, the questionnaire comprised questions evaluating the respondents overall concern about their current health, smoking status and chronic disease. The phrasing of each question used in this study is presented in the Supplementary materials, Table S1.

In the present study we included questions regarding eight lung cancer symptoms. Specific lung cancer symptoms are defined in the Danish lung cancer guidelines as prolonged coughing (>4 weeks), shortness of breath, haemoptysis, prolonged hoarseness (>4 weeks) and changes to a familiar cough among adults older than 40 years with a relevant smoking history. Coughing and hoarseness were considered prolonged if onset was reported as more than a month ago (Supplementary materials, Table S1). In addition, non-specific symptoms such as weight loss, loss of appetite and tiredness should also raise suspicion of lung cancer, both alone and in combination with the specific lung cancer symptoms9.

Register data

Socioeconomic data were obtained from Statistics Denmark by using the CRS numbers (28, 35, 36). The variables of interest were highest obtained educational level, labour market affiliation, and ethnicity. Data on vital status were obtained from the Danish Health Data Authority (38).

Statistical analysis

Individuals who died prior the data collection period and individuals exempted from digital mail due to severe illness, cognitive issues, language barriers, migration, no access to computer or insufficient Internet at home (approximately 7%) were ineligible for study28.

We only included respondents 40 years or older in the analyses according to the Danish lung cancer guideline9, and individuals who had not answered the last included question from the survey were excluded. To compare symptom concern and influence between different risk groups, both individuals who never, formerly, and currently smoked were included in the analyses. For coughing and hoarseness, only symptoms experienced for the first time more than four weeks prior to the survey were included in the analyses.

For each specific and non-specific lung cancer symptom, we used descriptive statistics to calculate the prevalence of symptoms and proportions of GP contacts, symptom concern and influence on daily activity.

The following covariates were included in the analyses: age groups (40–54 years, 55–69 years and over 70 years); smoking status (never smoking, former smoking, current smoking)29; symptom concern (none at all, slight, moderate, quite a bit, extreme); symptom influence on daily activities (none at all, slight, moderate, quite a bit, extreme); concern about current health (none at all, slight, moderate, quite a bit, extreme); highest obtained educational level (low (<10 years); middle (10–15 years) or high (≥15 years)); labour market affiliation (working, pension, out of workforce and disability pension); and ethnicity (Danish or immigrants/descendants of immigrants).

Per Danish legislation, reporting of data on individuals numbering fewer than four is not permitted, thus haemoptysis is only reported in some of the descriptive analyses due to too few observations.

We analysed the associations between smoking status and symptom concern and symptom influence using multivariable ordered logistic regression models. We estimated the odds of the symptoms being perceived as concerning or with influence on daily activities for each lung cancer symptom, both separately and for the combinations of two symptoms. Smoking status was included in the analyses as an explanatory variable. The models were adjusted for gender, age, concern about current health, chronic disease and socioeconomic factors.

Finally, we utilised multivariable logistic regression models to analyse the associations between symptom concern, symptom influence, concern about current health, and GP contact about at least one specific, or non-specific lung cancer symptom. Due to power issues the categories of quite a bit and extreme significance were merged into one. For individuals reporting more than one symptom, the symptom with the highest degree of concern or influence, respectively, were accounted for. The analyses were stratified by smoking status and adjusted for potential confounders: gender, age, symptom concern, symptom influence on daily activity, concern about current health, chronic disease and socioeconomic factors.

Data analyses were conducted using STATA version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All tests used a significance level of p < 0.05.

Inclusion and ethics

The respondents were informed that participation in the study was voluntary. In the invitation letter thorough information about the purpose and content of the questionnaire was given. Respondents who had questions to the study were offered the opportunity to contact the project group by phone or email. The respondents were informed there would be no clinical follow-up and instructed to contact their doctor in case of concern. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at University of Southern Denmark (Case no. 21/29156) and by the Danish Data Protection Agency (j.no. 2011-41-6651) through the Research and Innovation Organisation (RIO), University of Southern Denmark (Project number 10.104).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

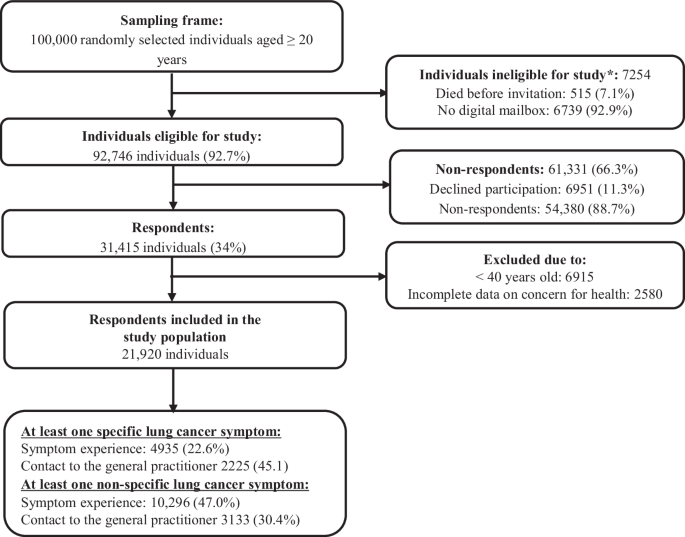

Of the 100,000 randomly selected invitees, 7254 (7.3%) were not eligible because they had died before invitation or had no digital mailbox. Of the 92,746 remaining individuals, 31,415 (33.9%) answered the questionnaire. After exclusion of individuals younger than 40 years old and 2580 individuals with incomplete data due to missing values on relevant items, this study included a total of 21,920 respondents, Fig. 1.

Flowchart.

Proportions of symptoms, GP contact and symptom significance

In total 4935 (22.6%) individuals reported at least one specific lung cancer symptom and (45.1%) contacted the GP, while 10,296 (47.0%) reported at least one non-specific lung cancer symptom with one out of three (30.4%) reporting GP contact, Fig. 1. Prolonged coughing was the most frequently reported specific lung cancer symptom (14.3%), while tiredness was the most frequent non-specific symptom (45.6%). Proportions of GP contact ranged from 29.9% for loss of appetite to 59.8% for shortness of breath, Table 1.

No symptom concern was reported by between 16.3% (shortness of breath) and 40.0% (prolonged coughing) of the respondents. The proportion of extreme symptom concern ranged from 2.4% (prolonged coughing) to 8.8% (changes to a familiar cough), Table 2. No influence on daily activities was reported by between 6.3% (tiredness), and 30.7% (prolonged coughing). Extreme symptom influence ranged from 2.4% (prolonged coughing) to 9.9% (changes in a familiar cough and tiredness), Table 2. In general, the proportion of GP contacts increased with greater symptom concern or influence on daily activity, except for the extremely high levels of concern, Table 2.

Smoking status and symptom significance

Tables 3 and 4 show the adjusted associations between smoking status and symptom concern/symptom influence on daily activities for each lung cancer symptom, when reporting both a single symptom and combinations of two symptoms. The univariable ordered regression models are shown in the supplementary materials Tables S2 and S3. Overall, individuals who currently smoked had higher odds of reporting concern regarding both specific and non-specific lung cancer symptoms compared to individuals who never smoked, with odds ratios (OR) ranging from 1.5 (95% CI: 1.2–1.8) for shortness of breath to 2.1 (95% CI: 1.1–1.4) for changes to a familiar cough, Table 3. The odds of high concern for individuals who formerly smoked also tended to be higher than for individuals who never smoked, yet not statistically significant. When experiencing combination of symptoms, the odds of reporting higher symptom concern among individuals who currently smoked seemed to increase, particularly for the combination of prolonged hoarseness and shortness of breath, respectively, and other specific lung cancer symptoms. Individuals who currently smoked and reported prolonged hoarseness and loss of appetite had the highest odds of higher symptom concern (OR 3.1, 95% CI: 1.6–6.0), Table 3.

The odds of reporting high influence on daily activities of shortness of breath increased for individuals who currently smoked when concurrently experiencing prolonged hoarseness (OR 1.8, 95% CI: 1.1–3.0), changes in a familiar cough (OR: 3.1, 95% CI: 1.1–8.4) and tiredness (OR 1.3 95% CI: 1.0–1.7), Table 4. Further, for tiredness, the odds of reporting higher influence on daily activities among individuals currently smoking appeared to be lower when concurrently experiencing prolonged coughing (OR: 1.5, 95% CI 1.2–1.8) and shortness of breath (OR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.2–1.9), compared to reporting solely tiredness (OR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.5–1.8), however the differences were small and confidence intervals overlapping, Table 4.

No differences in symptom concern were found in similar analyses regarding sex, whereas males in general had lower odds of high symptom influence, Supplementary Tables S4 and S5.

Smoking status, symptom significance and GP contacts

Table 5 shows the adjusted associations between symptom concern, symptom influence on daily activities, concern about current health, and GP contacts stratified according to smoking status. The univariable regression models are shown in Table S6. Overall, the likelihood of contacting the GP increased with rising symptom concern and influence regardless of smoking status. Extreme concern about current overall health also raised the likelihood of healthcare seeking, although to a lesser degree than concern about individual symptoms and mainly among individuals who never smoked, Table 5.

Discussion

We explored the associations between smoking status and perceived symptom significance among individuals with possible lung cancer symptoms in the general population and evaluated the influence of symptom significance on healthcare-seeking behaviour among individuals with different smoking status. Changes in a familiar cough and shortness of breath were the symptoms with the highest significance, as nearly one in ten individuals reported extreme symptom concern about these symptoms and considerable impact on their daily activities. For all symptoms, a substantial number of individuals reported no concern or influence at all. Overall, individuals who currently smoked, were more likely to report higher concern about both specific and non-specific lung cancer symptoms. The same tendencies were found for influence on daily activities, though mainly for shortness of breath, tiredness, and loss of appetite.

In general, reporting combinations of symptoms seemed to increase the likelihood of higher symptom significance. Yet, it appeared that reporting tiredness in combination with the specific lung cancer symptoms tended to decrease the odds of being influenced by tiredness. The likelihood of reporting GP contact with both specific and non-specific lung cancer symptoms increased with increasing symptom significance. Smoking status did not clearly modify this association, though the likelihood of healthcare seeking increased to a higher extent among individuals who never smoked.

A strength of this study is the large sample of individuals from the general population. The response rate of 34% is lower than in previous studies exploring symptoms and healthcare seeking in the general population13,30, but similar to another population-based study conducted during the same period31. The response rate was sought enhanced by two reminders, opportunity of contacting the project group and by drawing lots among respondents for a gift certificate. By investigating symptom significance in the general population and not among individuals with a specific diagnosis, we are able to enhance the understanding of how the general population comprehends and manages potential lung cancer symptoms, without the answers being biased by knowledge of a malignant diagnosis.

The data used for this study was collected in 2022. Similar data were collected in 2012 and analysed (Supplementary materials, Tables S7–S12). They showed identical tendencies, even though e.g., the Corona Virus 19 pandemic could have changed the perception of respiratory symptoms in the general population.

A risk of selection bias cannot be eliminated even though the sample was randomly selected. Individuals experiencing several symptoms or who are extremely concerned or influenced by their symptoms might be more prone to answer a questionnaire about symptoms and healthcare seeking, possibly resulting in an overestimation of symptom prevalence, healthcare-seeking behaviour, or symptom significance. On the other hand, this group may not have the surplus energy to answer a comprehensive questionnaire, causing an underestimation. Furthermore, individuals who are concerned about their symptoms or overall health may avoid responding to a questionnaire about symptoms to prevent increasing their anxiety. On the other hand, they may be motivated to participate by the opportunity to contribute their experiences to research, addressing issues that affect their daily lives. The study design attempted to minimise selection bias by offering the opportunity of contacting the project group in case of challenges32, however, the respondents are likely more technology literate than the non-respondents and individuals with no digital mail were excluded, which may induce some bias. Inclusion of individuals without digital mail was explored in the field test prior to the final questionnaire distribution, by inviting this group by postal letter. Very few of the postal invitees responded (<5%), but we received several calls from invitees and their relatives apologising for not being able to respond due to severe cognitive issues or diseases and asking us not to contact them again. Hence, we considered it ethically sound to omit the postal letter to avoid causing unnecessary disturbance of this vulnerable group33. The questionnaire was only available in Danish, excluding individuals who could not read in Danish. Although a higher percentage of the respondents were women, and the respondents were slightly older than the non-respondents, the respondents were found to be fairly representative of groups of general Danish population33.

Development of the DaSC II questionnaire followed COSMIN guidelines. The questionnaire was pilot tested among both academics and representatives of the general population, and afterwards field-tested in the target population to ensure content validity, comprehensibility, and avoid misunderstandings27.

The participants were asked to recall symptoms experienced within the preceding four weeks and indicate symptom significance and healthcare-seeking regarding each symptom. This time span was considered reasonable for adequate recall of symptoms and symptom-related factors. Self-reported smoking status is often underreported34 due to e.g., stigma, blame or embarrassment17,23. A misclassification of individuals currently smoking as having never smoked could underestimate the differences between e.g., individuals who currently and never smoked. Risk of misclassification was minimised by the survey being online and by emphasising that participation was anonymous.

We chose an ordered logistic regression model, as it is possible to include all categories for the outcome variable in an ordered manner, under the assumption that the ‘distance’ between the categories is equal across the range, i.e., fulfilling the proportional odds assumption. Some analyses, e.g., the stratified logistic regression models, were limited by power issues due to e.g., low number of individuals who formerly smoked and reported high symptom significance. Further, some of the differences implied in the results were small with overlapping confidence intervals. The regression models were adjusted for possible confounders, yet other variables such as type of occupation could have been important as well. For instance, some individuals may have jobs that require physical activity, while others may have jobs that heighten the risk of respiratory symptoms possibly influence the perception of these symptoms. This information was not available in this study. Other factors as alcohol consumption, body mass index and physical activity could act as cofounders as well but have previously showed ambiguous or low impact on healthcare seeking with lung cancer symptom24. Both are correlated with smoking status, yet in the context of perception of respiratory symptom we consider smoking history as essential even though some residual confounding cannot be eliminated.

The percentages of individuals reporting extreme symptom concern for both the specific and non-specific lung cancer symptoms in the present study were similar or higher than the findings in studies exploring symptom concern for gynaecological cancer symptoms35 and for studies exploring both symptom significance in general and for urological symptoms among men36,37. Both lung-, and gynaecological cancers may present with specific as well as non-specific symptoms, which are also common in the general population. This may explain why the perceived significance of these symptoms are comparable to the significance of more benign and common symptoms as headaches, backpain and urological symptoms36. This emphasises the challenge for both citizens and healthcare providers with interpretation of symptoms and balancing that the symptoms on one hand may be signs of cancer, and on the other may be benign and for some even self-limiting6,7,8.

In the present study, individuals who currently smoked, reported higher symptom significance than individuals who never smoked. Hence, it seems like the a priori hypothesis, that individuals who currently smoke normalise their symptoms may not be correct regarding symptom concern and influence. Yet, far from all with high symptom significance had contacted their GP. McLachlan et al. describe that individuals may try to explain their symptoms as caused by alternative benign conditions, and therefore do not act on them even though perceiving the symptoms as concerning38. Lung cancer screening has proven to contribute to early-stage diagnosis of lung cancer4,5. However, not all individuals are included in the risk group invited to screening, and far from all invitees will participate in screening39, hence timely diagnostics based on symptoms remains essential. This is particularly the case among individuals in high risk of developing lung cancer but low likelihood of perceiving their symptoms as significant, and probably also less likely to participate in the screening programms39,40 Hence, awareness of non-participants in screening programmes who may not interpret and act upon their symptoms are important for both GPs and in planning of screening programs. Furthermore, the influence of a screening without signs of disease may lead to a lower concern about symptom in the following period. Diagnostic imaging does not guarantee a risk-free period41, therefore, it should be emphasised to screening participants that acting upon symptoms is recommended, regardless of the screening result.

In line with Molassiotis et al.42, the present study implied that the experience of more than one lung cancer symptom seemed to increase the symptom significance. Molassiotis et al. also proposed that coughing plays a significant role in the interpretation and explanation of other symptoms such as shortness of breath and tiredness by suggesting that coughing may be used to normalise or explain other symptoms, lowering the perceived significance. In our study this was mainly seen for the influence of tiredness, which seemed to be lowered when reported together with prolonged coughing or shortness of breath.

A notable and gratifying result in the present study is that the combination of prolonged coughing and changes in a familiar cough increases the significance among individuals who currently smoke. Individuals with chronic disease may attribute their symptoms to existing disease, and consequently, postpone care seeking43. Therefore, it is of crucial for individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other respiratory conditions to act when a familiar symptom as cough changes to ensure timely diagnosis lung cancer.

Like demonstrated in prior studies35,36,37, a rise in the significance of symptoms is associated with an increased likelihood of healthcare seeking when it comes to symptoms related to lung cancer. Nevertheless, both heightened symptom concern and influence had a lesser impact on the probability of contacting the GP for individuals who currently smoked, as opposed to those who never smoked, yet with overlapping confidence intervals. This suggests that, even within the population at the highest risk of developing lung cancer, symptoms perceived as significant do not invariably result in healthcare seeking. This aligns with the findings of a qualitative study, which suggests that individuals who smoke are less aware, for instance of, the benefits of timely lung cancer diagnosis44. Other possible explanations include that individuals who currently smoke encounter more barriers to healthcare seeking16,17,45, and that their symptom appraisal may be influenced by pre-existing symptoms associated with smoking and existing chronic diseases46,47. Kaushal et al. showed that potential lung cancer symptoms are rarely identified as cancer symptoms and that the anticipated healthcare-seeking behaviour was not altered by co-morbidity46. Including chronic disease as potential confounder in the logistic regression models in the present study did not alter the associations with neither symptom significance nor GP contact. Additionally, fear of stigma23,48 and the concern about potential findings can serve a barrier to healthcare seeking16,17.

Symptom appraisal and the decision to seek healthcare is a multifaceted process influenced by various factors. Several theories address consultation behaviour and symptom appraisal49. In the Health Belief Model health behaviour decisions such as seeking care are argued to be triggered by the ‘cue to act’ such as of symptom experiences. Symptoms are interpreted and evaluated in an interplay of perceived severity, susceptibility, benefits and barriers. All of these depend on the individual’s self-efficacy defined as the confidence and ability to comprehend and act50,51. Symptom significance is embedded in more of the abovementioned factors, for instance, the perceived severity and susceptibility may depend on the impact of the symptoms on daily activity and perceived risk of illness, which in the case of respiratory symptoms is likely to be related to the individuals’ smoking history. This is supported by the findings by Black et al. who analysed healthcare-seeking behaviour among patients with lung cancer based on the common sense of illness self-regulation model. They also found that the emotional response to symptoms depend on the severity and perceived risk52,53. As such, we argue that symptom significance and smoking status could act as both barriers and facilitators of care seeking.

Self-efficacy, among others, may be expressed as the individual’s health literacy51,54. A recent study showed that health literacy challenges are associated with lower healthcare seeking with symptoms of lung cancer regardless of smoking status55. Nevertheless, current smoking has also been associated with lower levels of health literacy, which may influence the perception of the symptom significance as implied by Samoil et al.56. This remains to be investigated in population-based studies. Further, social relations, societal trends, and previous experiences with the healthcare system are also theorised to influence symptom appraisal and care-seeking behaviour, as emphasised by both Hay and Leventhal et al.53,57,58.

The symptoms examined in the present study may serve as indicators of lung cancer. The absolute risk of lung cancer when presenting with the symptoms, is though very low59,60, and the symptoms may more likely be indicators of benign conditions. Thus, it seems reasonable that not everyone is concerned or influenced by the symptoms.

Since a history of tobacco use is the most potent risk factor for developing lung cancer, knowledge about how smoking status influences perceived symptom significance and modulates healthcare-seeking behaviour is important for future healthcare planning, education and public awareness campaigns. GPs, and other healthcare professionals may play a crucial role in disseminating information on this topic to both the general population and specific patients. The increased symptom significance among individuals who currently smoke, as found in the present study, emphasise that this group may perceive their symptoms as severe, and that they may be aware of their susceptibility, but not necessarily prompt healthcare seeking. The GPs could play an important role in articulating the benefits of acting on symptoms, especially when concerned or bothered, for instance in planned consultations regarding existing disease. A challenge lies in raising the awareness and vigilance of lung cancer symptoms among individuals at risk while avoiding alarming the general population unnecessary.

The perception of symptom significance could be considered in future implementation of lung cancer screening, where a screening test without signs of disease may diminish the level of concern for symptoms, and potentially hamper the decision of seeking care. Thus, participants, who comprise of high-risk individuals, should be informed that acting on symptoms is important regardless of the results of recent screening.

Overall, individuals who currently smoked were more likely to perceive their lung cancer symptoms as significant, and individuals who reported high symptom significance were more likely to seek healthcare with both specific and non-specific lung cancer symptoms. The significance of symptoms appeared to have a less pronounced influence on healthcare seeking among individuals with a history of current smoking. This suggests that these specific groups may derive greater benefits from receiving support and encouragement to seek medical attention when experiencing concerns or discomfort related to symptoms that could be indicative of lung cancer. Consequently, such interventions could potentially reduce the likelihood of patient delay and improve the chance of timely diagnosis for lung cancer.

Responses