Description and characterization of pneumococcal community acquired pneumonia (CAP) among radiologically confirmed CAP in outpatients

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a frequent and potentially severe disease whose prognosis requires appropriate management as soon as possible after diagnosis1,2,3. The diagnosis of a CAP is complex, based on the combination of non-specific clinical symptoms, radiological criteria, and laboratory markers. Multiple pathogens, including bacteria and viruses can cause CAP, both as single agent or in combination4. In France and USA chest X-ray (CXR) is currently recommended to establish CAP diagnosis in primary care1,5.

Prior to the advent of antibiotic therapy, 95% of hospitalized pneumonias were attributed to Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP)6,7,8. Despite a decrease in its proportion, SP is still considered as the main causal agent of CAP in ambulatory settings9,10, as well as in hospital settings11,12,13. The reported proportion of hospitalized CAP due to SP ranges between 5% in the US4 and 19% in Europe14, but differences in study populations, periods, and settings, as well as differences in diagnostic testing methods likely contribute to significant variation in the proportions of reported pneumococcal CAP. In contrast, few studies have evaluated the proportion of pneumococcal etiology of CAP in outpatients15.

In general practice, CAP is most often diagnosed at an early stage and the clinical signs traditionally described in hospital-based studies are rarely found in their entirety16. Considering its potential severity, especially when the suspected causal agent is SP, it is important to identify as early as possible patients with probable pneumococcal CAP as they require prompt antibiotic treatment1,5. However, Musher et al. raised also the question of limiting treatment to symptoms in certain situations, as many CAPs are thought to be of viral etiology. They proposed a strategy limited to monitoring and symptomatic treatment for patients with clinical signs of CAP, without risk factors for bacterial infection, with symptoms of upper airway infection, and without biological signs of infection16.

In the present study, we aimed to analyze the prevalence and describe the characteristics of outpatients with radiologically confirmed pneumococcal CAP, managed in general practice in France.

Results

Investigators’ characteristics

Considering the study investigators, 55.2% (n = 153) were female and their mean age was 41.7 years (SD = 10.9), 76.1% of investigators were GP trainers, and most practiced in urban areas (62%, n = 168), with a mean number of patient consultations of 93 patients per week (SD = 33). Among the 277 investigators, 108 included at least one patient.

Patients’ characteristics

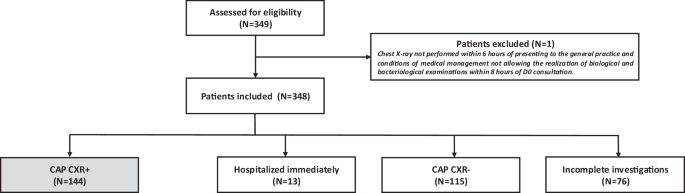

Considering the 348 patients with suspected CAP who were included, 144 (41.4%) had a CXR compatible with a CAP (CAP CXR+), while 115 (33.0%) had a CXR not suggestive of CAP (CAP CXR−) according to the local radiologist interpretation. Thirteen patients (3.7%) were immediately hospitalized without CXR being performed and 76 patients (21.8%) with incomplete investigations were not included in the analysis (Fig. 1). For the 144 patients with CAP CXR+, UAD and PUAT were performed for 127 patients, blood culture for 112 patients and sputum culture for 87 patients.

D0 Day 0 (date of inclusion), CAP community acquired pneumonia, CXR+ positive chest X-ray, CXR- negative chest X-ray.

Streptococcus pneumoniae and others pathogens detection

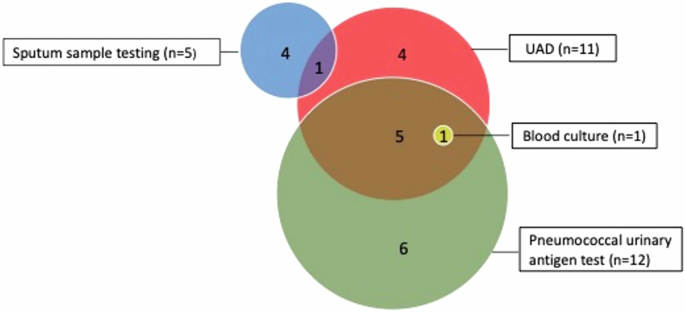

Considering the 144 CAP CXR + patients, SP was detected by at least one microbiologic test in 21 patients, all microbiological tests were negative for 66 patients. The remaining 57 patients were classified as undetermined CAP. Among the 144 CAP CXR + patients included in the analysis, the proportion of CAP due to SP was 14.6% (21/144) (95% CI 8.8–20.3%). When considering only CAP patients with complete testing for pneumococcus, the proportion was 24.1% (21/87) (95% CI 15.1–33.1%). SP serotypes were identified for 12 patients (22F (n = 3), 3 (n = 2)/8 (n = 2)/9N (n = 1)/11A (n = 2)/19F (n = 1)/20 (n = 1)). The microbiological tests by which SP were identified are described in Fig. 2.

Among the 144 patients CAP CXR+, microbiological tests were performed as follows: sputum sample testing for 87 patients, UAD (serotype-specific multiplex urinary antigen detection) for 127 patients, blood culture for 112 patients, pneumococcal urinary antigen test for 127 patients. UAD UAD serotype-specific multiplex urinary antigen detection test.

Among the 21 pneumococcal CAP and the 66 non-pneumococcal CAP (whom only two received antibiotic treatment prior to inclusion), the three most frequent symptoms observed were cough, tiredness and fever (Table 1).

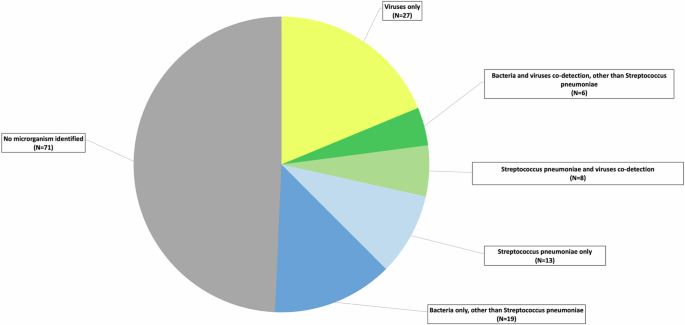

Among the 144 CAP CXR + patients, a pathogen was detected in 73 (50.7%): one or more bacteria were identified in 32 (including 13 SP) (22.2%), one or more viruses in 27 (18.8%), and both bacteria and viruses in 14 (including 8 SP) (9.7%). (Fig. 3)

Viruses only (N = 27), Human Bocavirus (N = 1), Adenovirus (N = 2), Enterovirus and Rhinovirus (N = 9), Metapneumovirus (N = 5). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (N = 1), Parainfluenza virus (1,2,3,4) (N = 1), Influenza virus B (N = 1), Influenza virus A (N = 5), Influenza virus A + Enterovirus + Rhinovirus (N = 1), Influenza virus A + Parainfluenza virus (1,2,3,4) (N = 1), Bacteria and viruses’ co-detection, other than Streptococcus pneumoniae (N = 6), Enterovirus + Rhinovirus + Neisseria + Escherichia coli + undetermined bacteria (N = 1), Enterovirus + Rhinovirus + Staphylococcus aureus (N = 1), Enterovirus + Rhinovirus + Mycoplasma pneumoniae (N = 1), Metapneumovirus + Staphylococcus capitis (N = 1), Parainfluenza virus + Enterovirus + Rhinovirus + Streptococcus alpha-hemolytic + undetermined bacteria (N = 1), Influenza virus A + undetermined bacteria (N = 1), Streptococcus pneumoniae and viruses’ co-detection (N = 8), Streptococcus pneumoniae + Enterovirus + Rhinovirus (N = 3), Streptococcus pneumoniae + Respiratory syncytial virus (N = 1), Streptococcus pneumoniae + Influenza virus B (N = 1), Streptococcus pneumoniae + Influenza virus A (N = 3), Streptococcus pneumoniae and bacteria co-detection (N = 13), Streptococcus pneumoniae (N = 10). Streptococcus pneumoniae + Haemophilius influenzae (N = 1), Streptococcus pneumoniae + Neisseria + undetermined bacteria (N = 2), Bacteria only, other than Streptococcus pneumoniae (N = 19), Undetermined bacteria (N = 1), Streptococcus beta-hemolytic (N = 1), Streptococcus alpha-hemolytic (N = 2), Streptococcus alpha-hemolytic + undetermined bacteria (N = 1), Streptococcus alpha-hemolytic + Escherichia coli (N = 1), Streptococcus alpha-hemolytic + Streptococcus beta-hemolytic (N = 2), Staphylococcus aureus (N = 4), Pseudomonas aeruginosa + Escherichia coli (N = 1), Haemophilius influenzae (N = 2), Chlamydiophila (N = 1), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (N = 3).

Discussion

In this study, we describe the clinical, biological and microbiological characteristics of patients with radiologically confirmed CAP treated as outpatients, most of whom had not received antibiotic therapy prior to inclusion. The prevalence of pneumococcal CAP was between 14.6% (95% CI [8.8–20.3%]) and 24.1% (95% CI [15.1–33.1%]) according to the analyzed population.

The diagnostic criteria for CAP used in our study, combining symptoms of systemic and lower respiratory tract infection associated with radiological signs of CAP, are comparable to data in the literature3,17. The patients included in this study were younger than those described in hospital-based studies (30.1%), with few risk factors for invasive pneumococcal infection and low pneumococcal vaccination rate (6.3%). These characteristics are consistent with data described in other studies conducted in general practice15,18.

The proportion of CAP due to SP was higher than previously reported by Jain et al. in hospitalized patients in the US4 (5%) and Flamaing et al. for outpatients in Belgium15 (4.8%). Our findings are comparable to the results of a systematic literature review based on data published until 2013 and supplemented by a meta-analysis estimating that the proportion of CAPs attributable to SP was 27.3% (95% CI [23.9% – 28.9%]) with only 5 of the 35 studies analyzed involving non-hospitalized patients11. Our findings are also comparable with a meta-analysis evaluating the role of SP in community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe (19.3%)14. Likely, our results can be explained to a large part by the use of comprehensive per-protocol microbiological tests, including UAD and by the fact that most study patients were not treated with antibiotics prior to enrollment. Comparatively in the Jain et al. study UAD was not performed, and in Flamaing et al., only pneumococcal urinary antigen test was performed, which may explain why SP was more frequently identified in our study.

A pathogen was identified in 50% of CAP, in our study. This percentage can be explained by the use of comprehensive microbiological tests, and it is comparable to the data in the literature regarding hospitalized patients4,19.

This study has some limitations. First, the small sample size for our study and the low number of patients included per investigator (only 39% of them included at least one patient) which may be related to the need to systematically perform a CXR. This can also be explained by the difficulties associated with carrying out biological and microbiological investigations in general practice and the time constraints associated with the study procedures in order not to delay the management of patients, which have probably limited the number of enrollments. Second, the use of CXR as a criterion for defining CAP is questionable. Indeed, CAP radiological diagnosis is difficult, the radiological manifestations can be delayed after the symptoms’ onset, and the radiological aspects of CAP may take the form of opacities with various characteristics. Radiological diagnosis is particularly difficult in the elderly20, and patients with obesity or chronic respiratory disease16. Studies show that an inter-observer variability is significant21. However, the use of a CXR increases diagnostic certainty and is still routinely recommended in France and the USA. Third, the choice of definition criteria of the non-pneumococcal CAP group might seem restrictive. Fourth, the investigators are not representative of French GP, they are younger and more involved in the training of medical students, but they were selected for their ability to handle requests for unscheduled care like patients newly diagnosed with a CAP suspicion.

SP remains a frequent cause of CAP, in general practice, with a prevalence in our population between 14.6% and 24.1%. Among patients with pneumococcal CAP, 33.3% had at least one risk factor for invasive pneumococcal infection and none were vaccinated with PCV13 and/or PPV23. In this population of outpatients, microbiological tests identified an exclusively viral etiology in 18.8% of patients. Further studies would be required to identify clinical and/or biological characteristics enabling general practitioners to guide their diagnostic and therapeutic decisions in cases of clinically suspected pneumonia.

Methods

Study design

PneumoCAP is a prospective observational study conducted between 1st November 2017 and 31st December 2019, which was carried out through a network of 277 French general practitioners (GP). Investigators were selected for their ability to screen and enroll patients newly diagnosed with a CAP suspicion. CAP was clinically suspected and all patients had to fulfilled the following criteria: age ≥18 years, presence of at least one general sign of infection (fever > 38.5°C measured by the patient or GP, heart rate > 100/min, respiratory rate > 20/min, global impression of severity (global impression of the general practitioner regarding the severity of the patient’s health condition, quoted yes or no)18, muscle aches—fatigue or chills and at least one sign of lower respiratory tract infection (cough, unilateral chest pain, purulent or non-purulent sputum, auscultatory abnormalities compatible with CAP)17.

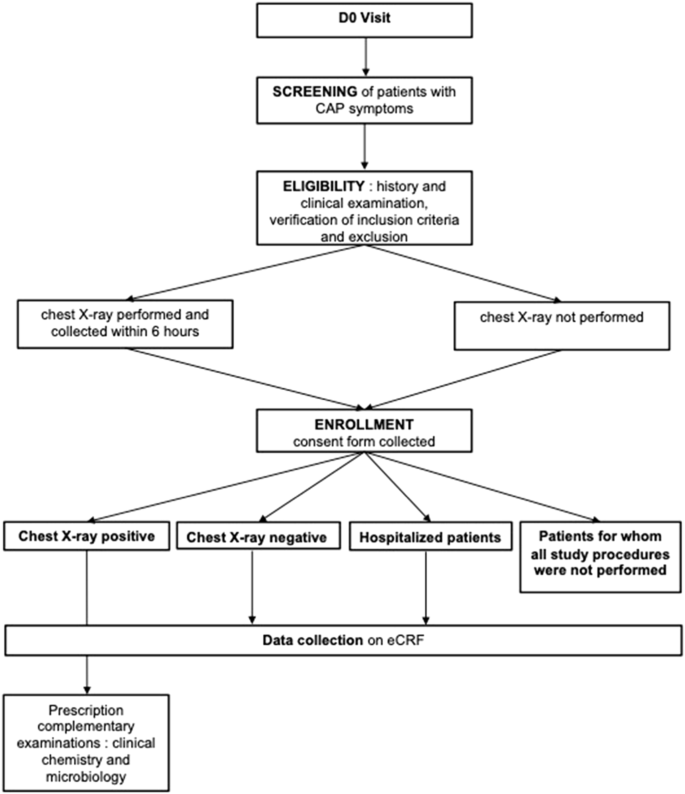

Study procedures

According to French guidelines1, investigators performed a CXR to all patients with CAP suspicion, as part of standard of care. After the CXR was performed, the investigators proposed to the patient to participate in the PneumoCAP study. For patients for whom it was not possible to perform a CXR as part of routine care (immediate hospitalization, or CXR not accessible), they were also proposed to participate in the study. Patients were included if they agreed to participate and signed the informed consent form.

For patients with a positive CXR, i.e. CXR compatible with a CAP according to local radiologist interpretation, clinical chemistry and microbiological tests were performed. Laboratory and microbiological samples were collected within 8 h after enrollment in local medical analysis laboratory.

For patients with negative CXR, i.e. CXR not compatible with a CAP according to local radiologist interpretation, clinical chemistry and microbiological tests were not ordered.

For patients requiring immediate hospitalization, neither the CXR nor the clinical chemistry and microbiological tests were ordered by the investigating GP.

For patients for whom all study procedures could not be completed, i.e. who did not wish to participate in the full study or for whom study procedures could not be respected (named “incomplete investigations”), the only data collected were limited to gender, age and the CRB65 score. (Fig. 4).

D0 Day 0 (date of inclusion), CAP community acquired pneumonia, eCRF online case report form.

Data collection

Patient’s demographic and clinical characteristics, medical history, information on medical conditions increasing risk for pneumococcal disease, pneumococcal vaccination status (PCV13 and/or PPV23) and influenza vaccination status according to medical record or declared by the patient, symptoms on inclusion, clinical examination data, were collected on day 0, by the investigating GP after interview and examination. All data were collected on an eCRF from day 0 until day 28 for all patients included, and up to day 90 for patients who were admitted to the hospital after enrollment.

Clinical chemistry tests included blood count, C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin (PCT) dosages were collected and performed in local medical laboratory. Microbiological testing included blood cultures, oropharyngeal swabs for multiplex real-time PCR for respiratory pathogens (Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, coronavirus 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), influenza A and B, parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, 3, and 4, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rhinovirus, enterovirus, adenovirus, bocavirus, R-GENE©, Biomerieux) and sputum Gram stain microscopy (with induced expectoration when possible). Sputum Gram stain microscopy and multiplex PCR were collected in local medical laboratory, multiplex PCR were shipped to be then performed in the same central laboratory in France. Urine sample for per-protocol testing was collected in local medical laboratory then frozen and shipped to the same central laboratory in France, then send to USA to be tested by pneumococcal urinary antigen test (PUAT) BinaxNOW S. pneumoniae® (Abbott Diagnostics), UAD serotype-specific multiplex urinary antigen detection test, UAD1, and UAD2 at Pfizer’s Vaccines Research and Development Laboratory (Pearl River, NY), identifying 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F 23F serotypes for UAD1 and 2, 8, 9N, 10A, 11A, 12F, 15B/C, 17F, 20, 22F and 33F for UAD 222,23,24,25.

Objectives

The main objective was to estimate the percentage of CAP associated with SP among radiologically confirmed CAP (CAP CXR+) in outpatients in general practice. The first secondary objective was to describe the characteristics of pneumococcal CAP and non-pneumococcal CAP. The second secondary objective was to describe microbiological characteristics of patients treated in general practice for a radiologically confirmed CAP.

Case definition of “pneumococcal CAP” was as follows: a patient with CAP CXR + and at least one positive SP microbiological test (blood culture, sputum culture, PUAT [BinaxNow®], UAD1/UAD2 [Pfizer Inc®]).

Case definition of “non-pneumococcal CAP” was as follows: a patient with CAP CXR + for whom all four SP microbiological tests mentioned above were negative for SP.

Case definition of “undetermined CAP” was: a patient with CAP CXR + for whom none SP microbiological test was positive for SP and not all four pneumococcal tests were performed.

Data analysis

Patient characteristics were reported by groups (radiologically-confirmed CAP, pneumococcal CAP, non-pneumococcal CAP, undetermined CAP), using frequency and percentage for categorical variables, and median and inter-quartile range values for continuous variables.

The percentage of pneumococcal CAP amongst radiologically confirmed CAP and its 95% confidence interval was estimated using the binomial distribution.

Ethics

The study was conducted as a collaboration between Pfizer and the French National Academic Council of General Practice (CNGE conseil). CNGE conseil was the study sponsor. The French health authorities (The French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products, ANSM) approved the study protocol and patient informed consent procedures. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent for inclusion. The protocol was registered in the clinicaltrial.gov website under the PNEUMOCAP acronym (NCT03322670). The Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes, Ile de France II. Paris N° 2016-A01537-44) approved the study protocol.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses