A 7-point evidence-based care discharge protocol for patients hospitalized for exacerbation of COPD: consensus strategy and expert recommendation

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic, progressive lung disease, accounting for 3.2 million deaths every year1. Acute exacerbation of COPD (ECOPD), defined as “an event characterized by dyspnea and/or cough and sputum that worsens over less than 14 days”, is an important event in the course of COPD because it causes significant deterioration of physical, mental and social health, hastens disease progression, increases the risk of dying and causes a substantial economic loss not only to the patient and his/her family, but also to the society2.

In-hospital mortality for ECOPD ranges from 2.5 to 25%3,4 and among those who survive, 25–55% get readmitted5. The 2-year and 5-year mortality rates after hospitalization for ECOPD are 26% and 58%, respectively6,7. Readmission rates for ECOPD are the highest among all chronic disease conditions8. In a systematic review of 57 studies from 30 different countries, readmission rates for COPD were reported to be 2.6–82% at 30 days, 11.8–45% at 31–90 days, 18–63% at 180 days, and 25–87% at 365 days9.

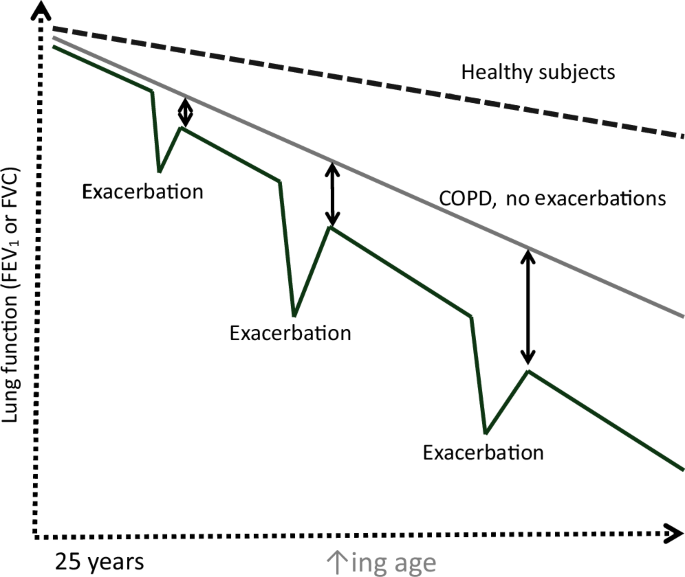

Between 5.2 and 30% of patients with COPD have more than 2 exacerbations every year necessitating hospitalizations10. Every episode of ECOPD affects the natural history of the disease, causing a steeper decline in lung function that does not return to its baseline value11 (Fig. 1). Exacerbations become more frequent as the severity of COPD increases, with more than 85% of the readmissions for ECOPD occurring in GOLD Stages III and IV12.

Accelerated rate of decline in lung function along with permanent loss of lung volume with each COPD exacerbation.

ECOPD causes a huge economic loss13. In the UK, it accounts for 60% of the £1 billion National Health Service expenditure on COPD14,15, while in the USA it accounts for 13 billion USD16. Koul et al. reported the median cost of ECOPD hospitalization in northern India to be USD 740 (IQR: 556−1060)17, while Salvi et al. report an estimated economic loss of over 6 billion USD for COPD hospitalization in India (manuscript in preparation). Severe COPD exacerbations resulting in hospitalization can be up to 60-times more expensive than mild or moderate exacerbations managed by primary care services18, and every subsequent readmission for COPD costs around 1.5-times more than the index admission19.

Preventing ECOPD and the hospitalizations associated with it is one of the most important goals in COPD management. Around 25–30% of COPD readmissions can be prevented with proper management20. In the United States, readmission rates are routinely used to assess the quality of care provided. Their national incentive and penalty program called Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program reduces payments to hospitals who have excess readmissions21. This initiative was based on the observation that only one-third of hospitalized patients with ECOPD receive ideal care22.

Planning a discharge during hospitalization for ECOPD offers a unique opportunity to identify patients at high risk for subsequent readmission or death and offer them individualized care that will minimize this risk. So far, the major emphasis has been on appropriate pharmacotherapy of COPD, however, there is a lot more to this care which can help prevent future COPD exacerbations. The aim of this article was to provide an evidence-based, practical strategy which physicians can use in their day-to-day practice to minimize the risk of future readmission and death before they discharge their COPD patients.

Nine key opinion pulmonologists from different geographic locations of India, which comprised of academicians and senior practicing physicians were invited to form an Expert Working Group (EWG). This group systematically and critically reviewed all available literature in the field of COPD exacerbations, debated and brainstormed key points and developed an evidence-based care bundle package that practicing physicians can offer as a part of their care to COPD patients before they are discharged.

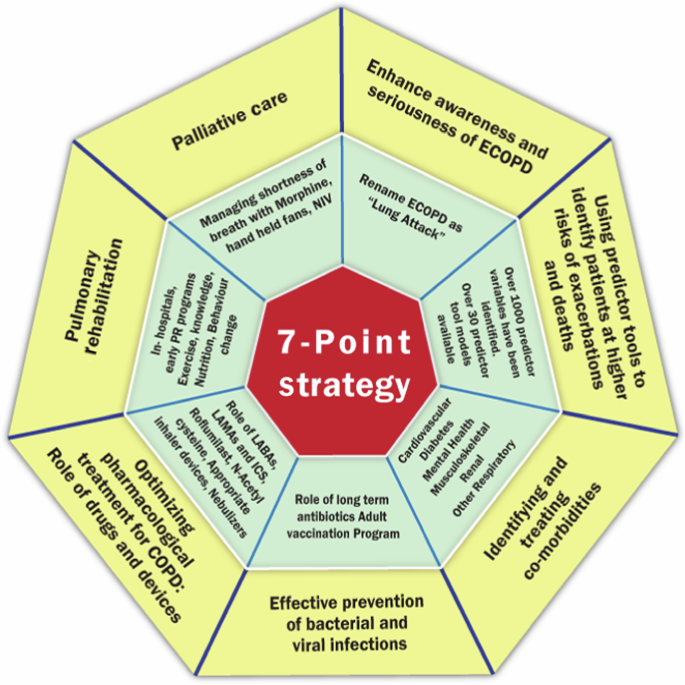

SS and DG performed a detailed literature search in PubMed, Google scholar and Google and identified all articles related to ECOPD. A total of 457 full text articles were collected. A presentation was made by SS to the EWG online after filtering all the scientific evidence. This was followed by a discussion, debate and brainstorming on key care packages that a physician can use based on scientific evidence. The EWG arrived at a 7-point pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approach which included: (1) enhancing awareness and seriousness of ECOPD, (2) identifying patients at risk for future exacerbations, (3) optimizing pharmacologic treatment of COPD, (4) identifying and treating comorbidities, (5) preventing bacterial and viral infections, (6) pulmonary rehabilitation, and (7) palliative care.

(I) Enhance awareness and seriousness of ECOPD

Mortality due to acute myocardial infarction (AMI), commonly called “heart attack” in the lay community has reduced substantially over the years, primarily because of greater awareness about the seriousness of the condition, early reporting when symptoms become worse and improved adherence to preventative strategies23. The 2-year mortality of ECOPD is higher than AMI24, yet ECOPD is not taken seriously by the patients, healthcare providers and the society at large. Less than 2% of COPD patients understand the meaning and seriousness of ECOPD and it has been argued that the respiratory community has neglected translating the term ECOPD, an event that substantially affects morbidity and mortality25.

Several innovative solutions have been suggested over recent years to overcome the lack of awareness and seriousness of ECOPD. The British suggested that ECOPD be labelled “COPD Crisis” or “COPD Flareup”26 so that patients understand the seriousness of the condition and take appropriate measures to prevent ECOPD. The Dutch have started using “Lung Attack” on similar lines as “Heart Attack”27,28 in order to enhance the awareness and seriousness of ECOPD.

(II) Identify patients at risk for future exacerbations

Preventing ECOPD is a primary goal in the management of COPD. It is important to identify patients who have a greater risk of readmission and ensure appropriate treatment before they are discharged.

A history of previous exacerbation has been shown to be the strongest predictor of future exacerbations. However, relying on this one factor alone can be inadequate given the high variability of exacerbation rates across the world. Search for other predictors have identified over 1000 variables, but the most common ones reported are: past history of ECOPD, age >65 years, male gender, increased severity of COPD (COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score >20 or COPD GOLD Stage III and IV), longer duration of COPD (>3–5 years), presence of comorbid conditions, worsening of ambient air quality, large fluctuations in ambient temperature, low socioeconomic status, use of inappropriate pharmacotherapy and poor compliance and adherence to inhaled medications29,30. The other predictors of ECOPD reported are poor exercise tolerance as measured by the 6-min walk distance (6MWD) test or the five-times sit-to-stand test (5STS)31, reduced hand-grip strength32, frailty measured by the 4-meter gait speed test33 and increased IgE levels34,35.

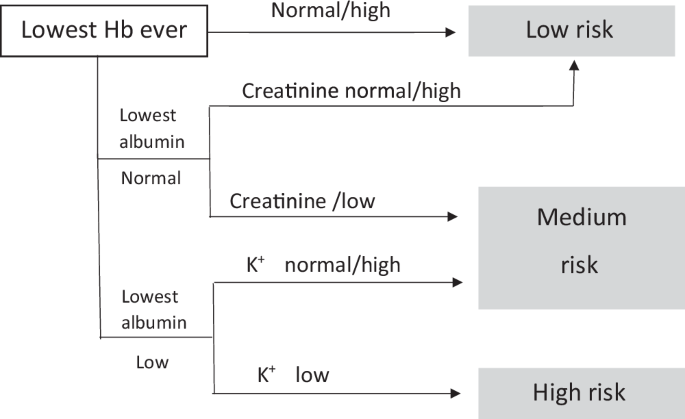

Several multivariate predictor models have been developed and reported from different parts of the world (summarized in Table 1). A systematic review identified 27 such models, but only 2 of these have been validated in other populations36. The Laboratory-based Intermountain Validated Exacerbation (LIVE) tool has been shown to predict high-risk patients who may benefit from early and specific interventions to avoid hospitalization and has been validated among 48,871 COPD patients37 (Fig. 2). More recently, a quantitative CT-based algorithm that included CT density gradient and airway structure measurements has been shown to predict ECOPD more accurately than history of previous exacerbation and the BODE index38, although routine HRCT before discharge may neither be practical nor feasible.

Laboratory-based Intermountain Validated Exacerbation (LIVE) Predictor tool for ECOPD (Adapted from ref. 37).

Machine learning and artificial intelligence tools have been used more recently to develop predictive models for ECOPD and these have been shown to improve accuracy of prediction39,40. One such model, ACCEPT (Acute COPD Exacerbation Prediction Tool) has been developed from COPD patients spread across 12 countries in North America, Europe, and Oceania41. It included 13 predictors (age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, number of moderate and severe exacerbations in the previous 12 months, observed vs predicted FEV1, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, use of domiciliary oxygen therapy, use of statins and type of inhaled COPD medication (LABA or LAMA, LABA + LAMA, ICS + LABA + LAMA), and was shown to provide a personalized risk profile at an individual level. However, studies showed that ACCEPT overestimated the predictive risk of ECOPD among those who had low exacerbation rates. The tool has been subsequently recalibrated after removing some of the variables such as drugs used to treat COPD and SGRQ which itself had 50 questions, and this improved the accuracy of ACCEPT 2.0 further42. Despite the availability of multiple predictors models, they may not be universally applicable unless they are validated and recalibrated for the local population43,44.

(III) Optimizing pharmacological treatment for COPD

The most rigorous and comprehensive data available for preventing ECOPD and hospitalization is the appropriate pharmacologic treatment of COPD45. Choosing the appropriate medication for long-term COPD management before the patient is discharged will have a significant impact on future rates of readmissions.

Inhaled long-acting beta-agonists, long-acting muscarinic antagonists, and corticosteroids

Both long-acting beta agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) improve respiratory symptoms and quality of life by reducing airflow limitation and decreasing air trapping. When given alone or in combination they have been shown to reduce the number of ECOPD46,47,48,49. Compared to LABAs, LAMAs cause greater reduction in ECOPD by 12% (7–16%) and hospitalization by 28% (13–31%)50,51,52,53. In patients with more severe disease, dual bronchodilators (LABA + LAMA) show superiority over placebo or either of the drug alone in reducing ECOPD54,55.

A meta-analysis of 54 randomized, controlled trials showed that ICS-containing drugs reduced moderate-to-severe exacerbations of COPD by 14% (7–20%), annual rate of exacerbation by 22% (14–28%), annual rate of exacerbation requiring hospitalization by 31% (12–46%), along with significant improvements in quality of life56. Until recently, ICS + LABA was recommended for stable COPD and for preventing ECOPD, especially among those who had peripheral blood absolute eosinophil counts >300 cells/µL and who had associated asthma, but the 2023 GOLD Strategy Report does not recommend this combination because triple drug therapy reduces rates of exacerbations by 15–36% compared to ICS + LABA and also reduces mortality significantly57,58. A meta-analysis of 6 studies comparing dual bronchodilator therapy versus triple drug therapy showed that triple drug therapy reduced moderate-to-severe exacerbation by 15–26%, increased time to first ECOPD by 14% and reduced morality by 30%59,60. A systematic review and Bayesian Network analysis of 9 different triple drug combinations (ICS + LABA + LAMA) showed that all triple drug combinations were equally effective in reducing ECOPD and mortality61.

Although inhaled corticosteroids improve lung function, oxygenation and reduce recovery time and hospital duration, they increase the risk of pneumonia by 50%62,63. Hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in COPD patients is 18-fold greater than those without COPD64. ICS should therefore be used with caution in patients with COPD, especially among those with a previous history of pneumonia, and if indicated, should be used in the lowest possible dose.

Choosing the appropriate inhaler device

The inhaled route is the safest, fastest, and most effective route for delivering drugs in patients with COPD. During discharge for ECOPD a considerable number of patients may not be capable of producing adequate peak inspiratory flow rates to overcome the internal resistance of dry powder inhalers (DPIs), while many patients may have difficulty coordinating inhalation with device actuation which is required for pressurized metered dose inhalers (pMDIs).

An estimated 60% of COPD patients use DPIs for their routine treatment65. With DPIs, patients need to produce a fast flow acceleration to generate turbulent energy inside the device to break up the powder while for pMDI the flow has to be much slower. The minimum peak inspiratory flow rate (PIFR) required while using a slow mist inhaler is 15–30 L/min, for pMDI is 30–60 L/min, while for a DPI it varies from 30 to >60 L/min. Low PIFR values are found in up to 44% of COPD patients65,66,67 and suboptimal inspiratory flow rates increase the risk of ECOPD and all cause readmissions68. The type of Inhaler device also influences adherence to long-term treatment. A Spanish study showed that patients who used DPIs were more likely to be non-adherent to their medication than those using pMDIs and those patients who visited their doctor once a month were more compliant69.

Critical inhaler errors are common among patients with COPD, regardless of their preferred inhaler device. A study from Korea reported that the percentage of critical errors in COPD patients for Turbuhaler, Breezhaler, Ellipta, Discus, Genuair, Respimat and pMDI were significant70. Adherence to treatment is also an important area that determines efficacy and likelihood of reducing ECOPD. A prospective cohort study found that the risk of 30-day readmission increases from 6 to 14% with every medication that was not taken properly71.

Home nebulization on discharge

Although inhalation devices such as spacers and valved holding chambers can be used with pMDIs to increase the efficiency of aerosol delivery, nebulized treatment provides patients with COPD an alternative administration route that avoids the need for inspiratory flow, manual dexterity, or complex hand-breath coordination72,73. Current evidence suggests that the efficacy of treatments administered to patients with COPD via nebulizers is similar to that observed in patients who used pMDIs and DPIs with proper technique74,75. COPD patients who will most likely benefit from nebulization therapy are included in Table 2 (adapted from ref. 76).

Several drugs can be delivered via the nebulized route (Table 3). With the availability of quieter and more portable nebulizer devices, nebulization has become a useful treatment option in the management of certain patients with COPD77. A considerable number of patients with COPD who remain breathless on high dose pMDIs and DPIs derive benefits from nebulized treatment78. With patients becoming increasingly satisfied with nebulized drug delivery, improved integration of nebulizers and nebulized therapies into the COPD treatment should lead to improved clinical, health and economic outcomes for patients with COPD79. Recent advances predict a bright future for nebulizers in patients with COPD80. However, certain limitations of nebulization include over reliance/dependence as felt by patients/caregivers, time taken and larger doses of drugs compared with inhalers76.

Roflumilast

Rabe et al. showed that 500 mcg of Roflumilast reduced the risk of ECOPD, but not hospitalization or need for systemic steroids81, while others showed that it can reduce the need for systemic steroid use by 18%82. Among those with history of moderate-to-severe exacerbation, roflumilast has been shown to reduce ECOPD by 17%83. In a real-world study of 995 COPD patients, roflumilast started within 30 days after discharge for ECOPD reduced subsequent exacerbations and readmissions, reduced healthcare utilizations and healthcare costs than in patients who delayed their roflumilast treatment. Patients with the ‘bronchitic’ phenotype of COPD and history of recurrent exacerbations are more likely to benefit from Roflumilast84.

Mucolytics cum antioxidants

Glutathione is the most important antioxidants in the lung and it gets depleted in patients with COPD. Replenishing the glutathione by using oral thiol supplements such as N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), Carbosysteine and Erdosteine have been shown to have beneficial effects in patients with COPD. These drugs also have mucolytic properties85. While the BRONCUS trial, which used N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) in a dose of 600 mg once daily did not show any benefit in preventing ECOPD86, the PANTHEON study reported that 600 mg twice daily reduced ECOPD by 22% (10–33%) in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD87. A post hoc analysis showed that NAC reduced exacerbation by 60% among those using bronchodilators only, but not among those using inhaled corticosteroids88. A meta-analysis of 11 studies have shown that NAC reduces the frequency of ECOPD in patients with chronic bronchitis by 19% (7–31%), while a meta-analysis of 38 studies exploring the role of mucolytics in chronic bronchitis showed a significant beneficial effect on hospitalizations by 32%, but the effect was heterogenous89. A more recent study showed that oral combination of natural propolis and N-acetyl cysteine reduced ECOPD significantly in a dose-related manner90. However, not all results with thiol-based antioxidants have shown beneficial effects91,92.

Role of domiciliary oxygen and non-invasive ventilation

Long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) at home is an established therapy that has been shown to reduce mortality. The impact of LTOT in reducing ECOPD was recently reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 studies which showed a significant reduction in the risk of re-hospitalizations [RR:1.54 (CI:1.28–1.85)]93. Recent work is exploring how to titrate the oxygen requirement in a personalized real-time manner using artificial intelligence94.

Domiciliary long-term non-invasive ventilator (NIV) in COPD patients require frequent hospital admissions has been shown to reduce the number of hospital admissions (28% vs 84.7%), ICU admissions (7.1% vs 56.9%) and ventilation requirements (3.6% vs 30.6%)95. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 randomized controlled trials in patients with hypercapnic COPD, rates of hospitalizations were shown to be reduced significantly by home NIV, although the evidence was of low to moderate quality96.

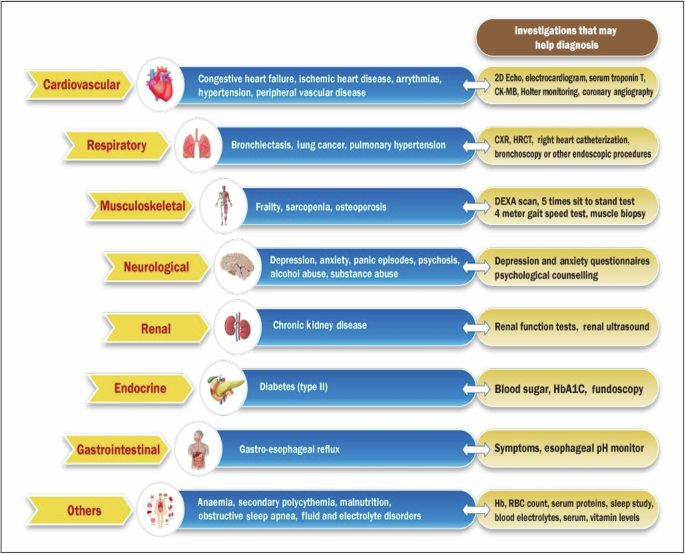

(IV) Identify and treat of comorbidities

COPD is now considered to be a multimorbid disease and presence of comorbidities is an important cause for re-hospitalization (Fig. 3). In a large Danish registry study of over 82,000 COPD patients, 82% got readmitted over 5 years after an index hospitalization for ECOPD, and among these 59% were for non-respiratory causes7. Risk of readmission increases by 47% for every single unit of increase in comorbidities12. More attention should therefore be focused on preemptive risk reduction for these comorbidities.

Co-morbid conditions commonly associated with ECOPD that merit attention before discharge.

COPD and cardiac comorbidities

Between 30 and 60% of COPD patients have concomitant cardiac disease. This relationship is likely because of shared risk factors, such as smoking, age, low physical activity and persistent low-grade systemic inflammation. A post hoc analysis of the IMPACT trial reported that cardiovascular adverse events increase by 2.6-fold in patients with moderate COPD and 21.8-fold in patients with severe COPD97. Breathlessness, fatigue, and chest pain on exertion are often misinterpreted as COPD-related symptoms, even when these symptoms could be due to underlying ischemic heart disease and heart failure98.

The cardiac comorbid conditions commonly associated with COPD are heart failure, ischemic heart disease, arrythmias, hypertension, and myocarditis. Congestive heart failure is the most common readmission diagnosis in patients with chronic respiratory diseases99,100 and accounts for 20% to 30% of COPD readmissions101,102. Use of long-acting beta agonists have been shown to be associated with increased risk of heart failure in COPD patients103,104.

In 2010, Donaldson et al.105 reported a 2.3-fold (1.1–4.7) increased risk of acute myocardial infarction between one to five days after ECOPD. A recent meta-analysis of 7 studies reported a 2.4-fold (1.4–4.2) increased risk of AMI for up to 30-days post ECOPD106. Elevated levels of troponin T are found in around 16% of patients hospitalized for ECOPD and these patients show a 6.3-fold (2.4–16.5) greater risk of mortality at 30 days107.

Role of beta-blockers in patients of COPD with coexistent cardiovascular disease

Physicians often avoid using β-blockers in patients with COPD due to concerns of adverse bronchospasm. However, a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials reported that β-blockers do not increase respiratory symptoms, reduce lung function or reduce response to inhaled β2-agonists108.

An observational study from 23 practices in Netherlands (N = 2230 COPD patients) reported that β-blockers reduced total mortality by 30% (14–41%) and ECOPD by 27% (17–37%)109. A subsequent systematic review of 15 studies reported that β-blockers reduce mortality by 28% (17–37%) and reduce ECOPD by 37% (29–43%)110. A more recent Danish study in COPD patients with hypertension among 1.3 million people showed that treatment with β-blockers reduced COPD hospitalization and mortality more than any other antihypertensive drug111.

Although many studies have shown that β-blockers improve survival of patients with a large spectrum of cardiovascular disease112, there are studies that show otherwise. Metoprolol failed to show any beneficial effects in terms of time to first ECOPD in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial113. Cardio-selective β-blockers score better over non-selective β-blockers in patients with COPD in terms of all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, heart failure hospitalizations and major adverse pulmonary events114. A study with bisoprolol which has a higher β1:β2 receptor selectivity ratio than metoprolol is currently underway115.

Role of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors in COPD

An observational, nationwide registry of 38,862 COPD patients from Denmark showed that use of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of ECOPD and mortality by 14%116. An earlier study reported that COPD patients who were using RAS blockers before hospital admission for ECOPD had a significant reduction in 30-day mortality117. A recent meta-analysis of 20 studies, including >500,000 COPD patients reported that use of RAS inhibitors was associated with reduced risk of death by 30% (22–39%), but failed to show any effect on ECOPD118.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

David Flenley coined the term Overlap Syndrome (OS) when he described Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) in patients with COPD and showed that they had a higher risk of mortality and ECOPD119. The prevalence of OSA in COPD varies from 15 to 42%120,121. Pulmonary Arterial hypertension in a common comorbid condition in COPD and is associated with higher rates of ECOPD and hospitalizations122. Managing OS and PAH before discharge could therefore potentially reduce future ECOPD.

COPD and mental health

Patients with COPD have a significantly higher risk of mental health problems that are often unrecognized and undertreated, and their presence significantly increases the risk of hospital readmission123. In a study from USA, Singh et al.124 reported that in patients hospitalized for ECOPD, 34% had depression, 43% had anxiety, 18% had psychosis, 30% misused alcohol, and 29% misused substances. Depression is associated with increased risk of short-term as well as long-term readmission, while anxiety is associated with frequent readmissions125.

(v) Prevent bacterial and viral infections

Most exacerbations of COPD are precipitated by viral and bacterial infections126. The common bacteria and viruses associated with ECOPD are listed in Table 4. Exposure to high levels of ambient air pollution has been shown to make COPD patients more vulnerable to respiratory viral infections, especially influenza virus A127,128.

In a recent prospective, multinational, observational study from Hong Kong, Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan, 197 moderate-to-severe COPD patients were followed over 1-year and underwent sputum examination by culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to examine presence of pathogenic bacteria and viruses during both stable states as well as during exacerbations. PCR was found to be 8 to 15-fold more sensitive in identifying presence of pathogenic bacteria than sputum culture methods. The influenza virus was 12-times more prevalent during ECOPD than stable COPD. Importantly, 67% of stable COPD patients showed presence of pathogenic bacteria in their induced sputum129. We have previously reported that stable COPD patients have very high numbers of pathogenic bacteria in their induced sputum, and this was associated with defective macrophage phagocytosis130. A meta-analysis of 17 studies reported that the weighted overall prevalence of respiratory viruses in patients with ECOPD was 39.3% (36.9–41.6%)131. More recently, the SARS-Cov2 virus causing COVID-19 has also been shown to be associated with ECOPD132.

Role of long-term antibiotics

A meta-analysis of 12 studies that included 2151 patients showed that compared with control treatment those receiving long-term macrolides had reduced COPD exacerbations by 60% (35–76%)133. In several small studies, erythromycin has been shown to reduce the incidence of ECOPD134,135. Moxifloxacin given in a pulsed manner (400 mg/day for 5 days, repeated every 8 weeks for a total of 6 courses) has been shown to reduce ECOPD by 25%136. Post hoc analysis indicated that patients with mucopurulent sputum at baseline experienced the greatest benefit. In addition to their antimicrobial effects, macrolide antibiotics have been shown to have anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects such as mitigating neutrophil-mediated lung damage and promoting mucociliary clearance, effects that occur at doses below the minimum inhibitory concentration for bacterial infections137,138. The 2020 British Thoracic Society Guidelines recommend that long-term macrolide therapy can be considered for patients with COPD who have more than three acute exacerbations requiring steroid therapy and one exacerbation requiring hospital admission per year139.

Vaccination in COPD

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 6 randomized, controlled trials reported that influenza vaccination reduced the incidence of ECOPD by 63% (36–89%)140. A recent study from China in 474 COPD patients reported that influenza and PPSV23 pneumococcal vaccination separately and together effectively reduced the risk of ECOPD by 70%, pneumonia by 59%, and related hospitalization by 58%141. A randomized, controlled trial from Spain showed that the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine prevented community-acquired pneumonia in patients <65 years with severe COPD by 80% (32–94%)142. A more recent study on hospitalization outcomes in COPD patients vaccinated with pneumococcal vaccine reported that vaccinated patients had better outcomes when hospitalized for ECOPD (need for assisted ventilation, length of ICU/hospital stay)143. Both PCV13 and PPSV23 are effective during the first 2 years, but the PCV13 offers further protection for up to 5 years144. The GOLD 2023 Strategy Report recommends that all patients of COPD should be given 5 vaccines:(1) influenza vaccine (annual) (2), pneumococcal vaccine (PVC13 and PPSV23) (once) (3), herpes zoster vaccine (single booster) (4), Pertussis vaccine (single booster) and (5) COVID-19 vaccine145.

(VI) Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR)

Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR) plays a key role in the long-term management of COPD. The evidence base supporting the benefits of PR in stable COPD is substantial, with 65 randomized, controlled trials contributing to the most recent Cochrane Systematic Review146. In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the role of PR in the acute setting (either during or shortly after a hospital admission for ECOPD). The latest review of the Cochrane Systematic Review of PR in the peri-exacerbation period identified 20 randomized, controlled trials and found that PR following ECOPD was associated with a 56% (9–79%) reduced risk of hospital readmission, but the results were very heterogenous147. A recent meta-analysis of 13 RCTs that examined the benefit of early PR in 866 COPD patients showed significant improvements in 6-min walk distance, shortness of breath and quality of life148. Data analysis of 1159 COPD patients undergoing PR showed that the proportion of patients who achieved a minimum clinically important difference were 85%, 86%, and 65% for COPD assessment test, Medical Research Council Questionnaire, and the 6-min walk distance, respectively149. Muscle dysfunction is common in patients admitted for ECOPD because of use of systemic corticosteroids, malnutrition, inactivity, systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and hypoxia. A comprehensive rehabilitation program has been shown to improve exercise capacity, lung function and mental health in patients with COPD150.

Traditionally, the exercise component of PR has often been described as the need to have specialized exercise equipment tools. However, a recent study highlighted that PR using minimal equipment showed clinical significant improvements in the 6-min walk distance and quality of life which was comparable with the exercise equipment-based programs151,152. Use of pedometers on smart watches or smart phones with progressive and customized targets in patients of COPD have been shown to improve the number of steps/day153. Locally adapted PR programs such as Tai Chi in China and Yoga in India have immense local value and acceptance154,155.

The uptake of PR is unfortunately poor156 and one of the reasons is the negative connotation associated with the word (akin to drug rehabilitation, natural disaster rehabilitation). Giving it a more positive name or acronym can have a beneficial effect157.

Prevention of risk factors

Many patients hospitalized for ECOPD continue to smoke tobacco. which further increases the risk of ECOPD, emphysema and lung cancer158. Smoking cessation can be more effective after hospitalization for ECOPD. Pezzuto et al.159 recently showed that up to 51% of patients hospitalized for ECOPD quit smoking within a month after discharge and showed significantly better improvements in clinical and functional variables as well as response to pharmacotherapy. Quitting smoking after hospitalization for ECOPD reduces symptoms, improves lung function, and reduces treatment intensity160.

Exposure to biomass fuel smoke in poorly ventilated kitchens, past history of poorly treated chronic asthma, past history of pulmonary TB, high levels of ambient air pollution, recurrent respiratory tract infections during childhood and occupational exposures are leading risk factors for non-smoking COPD161 and avoiding these post ECOPD will have beneficial effects.

Nutrition supplementation

Between 30–60% of COPD patients are found to be malnourished on admission for ECOPD and poor nourishment is associated with greater hyperinflation, worse lung function, reduced exercise tolerance and weak respiratory muscles that impair the ability to generate sufficient cough pressures for effectively expectorating secretions162,163,164,165.

Traditionally weight loss was considered an inevitable consequence of severe respiratory disease, and therefore not amenable to nutritional intervention. In fact, it was earlier suggested that wasting was an adaptive response, and that nutritional support might be detrimental with the provision of additional substrate, particularly in the form of carbohydrate, placing further burden on the respiratory system. However, systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported that malnutrition is amenable to treatment and results in significant improvements in both nutritional intake and nutritional status166. Improved nutrition is associated with significant improvements in functional capacity, respiratory muscle strength and quality of life167.

Use of oral nutritional supplementation in patients hospitalized for ECOPD has been shown to significantly reduce 30-day readmission rates, possibly by reversing the disturbed energy balance168,169. Adequate intakes of glucose, protein, fibers, vitamins, and zinc have been shown to be associated with improved ventilatory function170. Hand-grip strength has also been shown to improve after oral nutritional supplementation171. Malnourished COPD patients need more protein supplements (1.2–1.5 gm/kg/day) and calories (45 kcal/kg/day) and a weight gain of 1–2 kg has a big impact on their quality of life. Supplementation of Vitamins A, C, and D have been shown to have benefit among those who have a deficiency172,173,174.

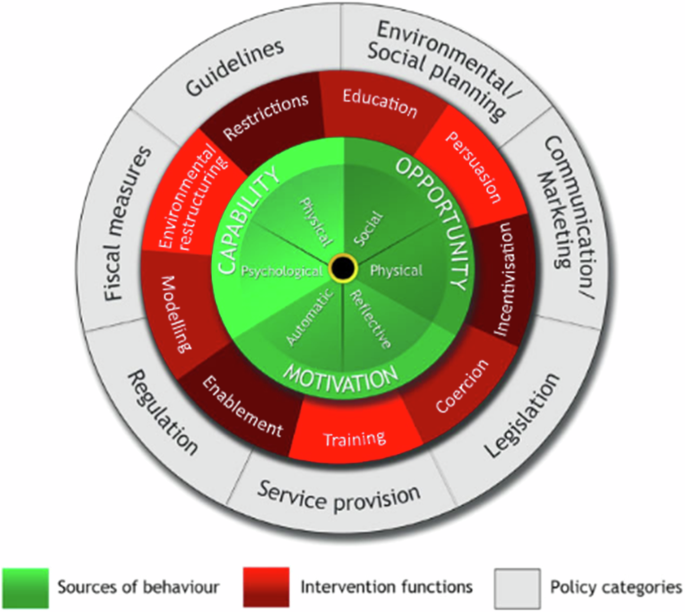

Behavior change strategies

Patients suffering with COPD can influence the course of their disease with their health behavior. It is therefore important to implement interventions that support behavior change. A recent study from Switzerland identified six target behaviors with 18 basic intervention packages using 46 behavior change techniques for patients of COPD175 (Fig. 4). When embedded in a broader self-management intervention complemented by integrated care components may have significant effects in preventing hospital readmissions for ECOPD176.

Six target behaviors with 18 basic intervention packages using 46 behavior change techniques for patients of COPD.

(VII) Palliative care

Conventionally, the term ‘palliative care’ has been associated with end-of-life care for cancer. However, it is now becoming increasingly recognized that palliative care can be delivered to patients with severe COPD and must go hand-in-hand from the point of diagnosis to ensure the best healthcare outcomes. Several studies have pointed out that PR when initiated from the point of diagnosis decreased patient symptom burden, improved quality of life of patients and their caregivers, and reduced hospitalizations.

Symptoms at the end of life in COPD are as severe or even worse than those who have advanced cancer177. Palliative care is an important component in the treatment of patients with severe COPD and has been shown to not only reduce the odds of 30-day readmission by up to 50%178, but also reduce the odds of heart failure by 73%179. Yet, palliative care in patients with COPD remains grossly underutilized180. Community-based palliative care provision in COPD has been shown to be associated with lower 30-day readmission rates181, but others have reported no benefit182. Early integration of palliative care into COPD care models endorsing modern multidisciplinary approaches appears to be essential, but barriers to accessible, open and effective palliative care conversations between patients and healthcare professionals need to be addressed183,184.

Breathlessness is a distressing symptom, uniformly faced at some point in the disease process in all patients with COPD. Although regular low-dose (<30 mg/day) sustained release morphine is recommended as first-line pharmacological treatment for persistent breathlessness among patients with severe COPD185, the results in the recent BEAMS study was disappointing186. NIV may be used as a comfort measure for patients by minimizing adverse effects. Use of hand-held fan may offer some relief187. The British Thoracic Society have designed and implemented a COPD Discharge Care Bundle, which comprises of the following components: (1) Review patients’ medications and demonstrate use of inhalers, (2) Provide written self-management plan and emergency dry pack, (3) Access and offer referral for smoking cessation, (4) Access for suitability for pulmonary rehabilitation, (5) Arrange follow-up call within 72 h of discharge188.

Summary and recommendations by the Expert Working Group (EWG) (Fig. 5)

Preventing ECOPD is one of the most important goals in the management of COPD. Before discharging the COPD, patient who has been hospitalized for ECOPD, it is important to ensure that he/she goes home with the best possible advice and intervention that will minimize the future risk of ECOPD and readmission. After reviewing the scientific literature and debating on key clinical issues, the EWG arrived at a 7-point management strategy that physicians could use in their clinical practice.

7- point strategy to prevent future ECOPD that can be adopted before discharging the patient.

To enhance the lack of awareness and seriousness about ECOPD in the lay community, the EWG unanimously agreed that there was a need to give a new label to ECOPD. After debate and discussion, the term ‘lung attack’ received the highest score. The EWG recommends that lung attacks receive wide publicity in the lay community through media and social channels. Like ‘heart attack’, ‘lung attack’ will help patients understand the seriousness of ECOPD, take necessary steps to manage their COPD better and report early when their symptoms start getting worse.

Identifying patients who are at a greater risk of having another ECOPD or hospitalization is crucial to offer them specialized preventative care. Although several predictors and predictor tools have been developed, they need to be validated/recalibrated to the local population before they can be used. The EWG members rated the following top 5 predictors based on their experience (out of a score of 10); previous hospitalization for ECOPD (9.0), poor care support (7.8), inadequate and inappropriate pharmacotherapy (7.5), incorrect use of inhaler devices (7.3) and presence of co-morbidities (7.0). These along with other key predictors reported earlier could be used to identify individuals at greatest risk.

Appropriate pharmacotherapy for COPD is the key to preventing future exacerbations. The EWG recommends long-acting bronchodilators (LAMAs and LABAs, either alone or in combination) as the cornerstone of COPD management. Emphysema predominant COPD should be treated with bronchodilator only (LAMA or LAMA + LABA). COPD patients with recurrent exacerbations and concomitant asthma should be treated with triple drug therapy, preferably through a single inhaler. Budesonide has a better safety profile than Fluticasone for pneumonia risk and should be preferred, but the dose should be kept to its minimum, and whenever possible should be withdrawn. Roflumilast may be added in patients who have the chronic bronchitis phenotype. Antioxidant mucolytics such as N-Acetyl Cysteine have shown benefit when given in a dose of 600 mg twice daily. Choice of inhalers (DPI or pMDI) and the correctness of use is crucial to ascertain before discharging the COPD patients’ home with a low PIFR should be given a pMDI with spacer. The nebulizer route may be useful in some at least during the first two weeks after discharge (Fig. 6).

Clinical scenarios where maintenance treatment with nebulizers is most appropriate in elderly COPD patients.

All patients admitted for ECOPD must undergo evaluation for comorbid conditions because they account for over 50% of future readmissions. Cardiovascular diseases such as congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, arrythmias and hypertension are common in patients with COPD but remain undiagnosed and untreated. Routine cardiac investigations followed by appropriate treatment with cardio-selective β-blockers and RAS inhibitors will help reduce readmissions. Diabetes is a common comorbid condition and the use of Metformin has been shown to be particularly helpful189,190. Mental health is most often neglected in patients with COPD that merit appropriate pharmacotherapy and behavioral therapy.

ECOPD is commonly caused by bacterial and viral infections. Preventing these with antibiotics and vaccination is one of the key preventative strategies for ECOPD. Long-term Azithromycin and other macrolides have shown promise, but care must be taken to avoid drug side effects and bacterial resistance. Long-term macrolide therapy can be considered for a minimum of 6 months and not more than 12 months. Vaccination is a key intervention that reduces the risk of future exacerbations. Table 5 lists the vaccines recommended by the EWG.

The choice of inhaler device should be individualized based on cost, patient preference and likelihood of adherence to treatment. Technique for each inhaler device should be checked during every medical visit. Wherever available, PIFR measurements should be done to optimize inhaler device selection. Nebulizer therapy may be preferred during the first 2 to 4 weeks after discharge and then evaluated during the subsequent follow-up visits.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is an important intervention that reduces future risk of ECOPD and improves quality of life. PR should be started as early as possible, preferably even in the hospital before discharge and needs to be continued regularly for a long time. Home rehabilitation is gaining widespread recognition and advising locally relevant exercises such as Tai Chi or Yoga should be encouraged. All patients should be advised to minimize their exposure to triggering factors. Tobacco cessation advice during ECOPD hospitalization in smokers has greater chances of success and every effort should be made to help patients quit smoking. Non-smoking risk factors and exposure to indoor and outdoor pollutants should be minimized. Malnutrition is common in patients with COPD and should be treated with appropriate protein and vitamin supplements along with adequate calories. Behavioral therapy is gaining recognition as an important component of PR.

The EWG recommends that Palliative Care should be included routinely in COPD care, especially among those with severe and very severe COPD and those who have disabling breathlessness, pain, fatigue, depression, confusion, and anorexia. Low-dose morphine, use of hand-held fan and palliative NIV may help alleviate disabling breathlessness.

In summary, the 7-point care bundle package if implemented successfully will have a significant impact on reducing mortality and the future risk of rehospitalization for ECOPD.

Responses