Improving asthma care in children: revealing needs and bottlenecks through in-depth interviews

Introduction

Globally, asthma is the most common chronic disease in children, occurring in 7% of them in the Netherlands1. Current trends indicate that this percentage is rising, which poses a significant disease burden2,3,4. To minimise the impact of childhood asthma on daily life, achieving good asthma control is essential. Uncontrolled asthma can have lasting effects on quality of life and lung development5. To achieve optimal asthma control, it is crucial for both parents and children to develop effective self-management skills, including accurate symptom recognition, adherence to prescribed therapy, proper inhaler technique, clear escalation plans, awareness of when to seek urgent care during exacerbations, and regular follow-up with healthcare providers6,7,8. Shared decision-making (SDM) plays a crucial role in treatment collaboration, enhancing adherence to treatment plans and improving overall outcomes6.

Paediatric asthma care varies across countries. In the Netherlands, both general practitioners (GPs) and paediatricians manage asthma in children. GPs handle initials assessments and treatment, following guidelines based on Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA)9,10, deciding whether to treat or refer patients to secondary care. Both primary and secondary care aim for optimal asthma control with minimal medication, supported by regular structured consultations to review treatment plans. Healthcare is funded through mandatory insurance, covering GP services and while annual asthma reviews are not directly incentivized, GPs are expected to provide comprehensive chronic care, including asthma management.

Routine follow-up of asthma patients in primary care often falls short11,12. Evidence highlights underdiagnosis, overdiagnosis, undertreatment and overtreatment in both the Netherlands and Europe12,13,14,15,16. Undertreatment worsens asthma control and risks long-term health damage, while overtreatment raises healthcare costs and increases medication side effects5. These challenges underscore the need for a structured care pathway with clear protocols6,17. Previous initiatives aimed to improve coordination between healthcare providers, but many children still experience uncontrolled asthma, impacting their daily lives13. A comprehensive review of paediatric asthma care, considering all stakeholders’ perspectives, is essential.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the current state of paediatric asthma care in the Netherlands from the perspectives of children, parents and healthcare providers, aiming to identify areas for improvement. Moreover, by identifying challenges and needs in the current paediatric asthma management, directions for a more comprehensive care pathway can be identified.

Methods

A qualitative exploratory study was conducted using semi-structured, in-depth interviews and thematic inductive analysis to evaluate representative insights into paediatric asthma care18. The inductive approach allows for flexibility in the interview process while still enabling the identification of common themes and patterns across the data. The scope of the study included paediatricians, nursing specialist/pulmonary nurses, GPs, and patients/parents. The study was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee (METC 2023-3635).

Sampling and recruitment

The study employed a combination of purposive and snowball sampling to ensure various perspectives while including participants from diverse populations. Purposive sampling was used to minimise observer bias and initially to select key stake holders, such as paediatricians, nursing specialist/pulmonary nurses and GPs, ensuring the inclusion of relevant expertise. Snowball sampling was subsequently applied, leveraging recommendations from initial participants to identify additional individuals. This dual approach facilitated the collection of rich, varied insights while minimising potential bias associated with non-response.

Patients with diagnosed asthma aged 6–18 years were invited to participate upon recommendation of their healthcare providers, following verbal informed consent. Healthcare providers, including GPs, nursing specialist/pulmonary nurses and paediatricians, were approached via email invitations. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to interviewing, and participants were advised of their right to opt-out at any stage. Recruitment was conducted both nationally and regionally to maximise diversity.

Heterogeneity was prioritised in the recruitment process to capture a wide range of perspectives. For patient participants, this included variations in follow-up frequency, geographic location, relationship quality with healthcare providers and severity of asthma. For healthcare providers, efforts were made to include experiences from different disciplines and geographical regions. These factors were chosen to reflect the diversity of experiences within the population of children with asthma, their families and the healthcare professionals involved in their care.

Data collection

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted using an interview guide developed with input from experts in paediatric asthma care, qualitative research and relevant literature. The guide focused on themes such as the patient journey, SDM and future perspectives on paediatric asthma care. The interview guides can be found in Supplementary Material 1.

Two researchers conducted the interviews: one clinician (without a doctor-patient relationship) and one trained qualitative researcher. This pairing helped balance clinical insight with qualitative research expertise and mitigate power imbalances. Additionally, a process of reflexivity was maintained throughout both the interviews and the analysis to enhance objectivity and to ensure that the perspectives of both researchers were carefully considered.

Interviews were held in Dutch, lasting 60–90 min, either face-to-face or online and were recorded, transcribed, and anonymized. Notes were taken to improve data triangulation. The sample size was determined by data saturation, with interviews continuing until no new significant themes emerged19. Quotes were translated into English during manuscript preparation.

Analysis

A thematic approach was chosen as the method of analysis for this study, according to Braun and Clarke18. This analysis identifies, analyses and reports patterns or themes within qualitative data. In this study, thematic inductive analysis was used to analyse the semi-structured in-depth interviews. This method allowed for identification of key themes and patterns in the data through an iterative process of coding and categorisation. The analysis was carried out by two independent coders who met regularly to discuss coding and ensure consistency.

The coding process began with open coding, in which codes were assigned to individual data points or phrases, based on their content. These codes were then organised into higher-level categories based on similarities and relationships between them. After this, axial coding was performed iteratively to refine and deepen the categories, exploring subthemes and underlying patterns18. Categories were continuously refined and revised as new data were analysed, and were systematically compared across all transcripts to ensure consistency and validity. Additionally, themes emerging from the data were compared with those outlined in the interview guide at each stage of the analysis to assess alignment and identify new insights.

Data triangulation

To ensure that the data could be triangulated, we remained in constant dialogue with various stakeholders throughout the study and regularly shared and reflected on findings. The findings were frequently discussed in the focus group and research team until useful themes developed. This iterative process validated and enriched the data, incorporating varied perspectives and insights18. The active collaboration aimed to strengthen the reliability and completeness of the research findings.

Trustworthiness

To ensure the trustworthiness, this inclusive approach allowed us to capture diverse perspectives and experiences, enhancing the credibility and transferability of our findings. Stringent data analysis techniques were employed, and an audit trail was maintained to ensure reliability, objectivity and transparency in the research process18.

Results

Thematic inductive analysis revealed four key themes, offering a comprehensive exploration of perspectives on paediatric asthma care across different stakeholders and regions (Table 1, Fig. 1). Key themes comprised of:

-

(i)

General view on current paediatric asthma care, emphasising overarching perceptions and attitudes from all stakeholders;

-

(ii)

Fragmentation and lack of continuity in paediatric asthma care, highlighting critical gaps, particularly between primary and secondary care, as well as barriers within primary care;

-

(iii)

Barriers to effective SDM in paediatric asthma care, barriers and current view on paediatric asthma management

-

(iv)

Recommendations for improvement in paediatric asthma care, outlining feasible steps for addressing gaps, fostering collaboration and improving continuity of care.

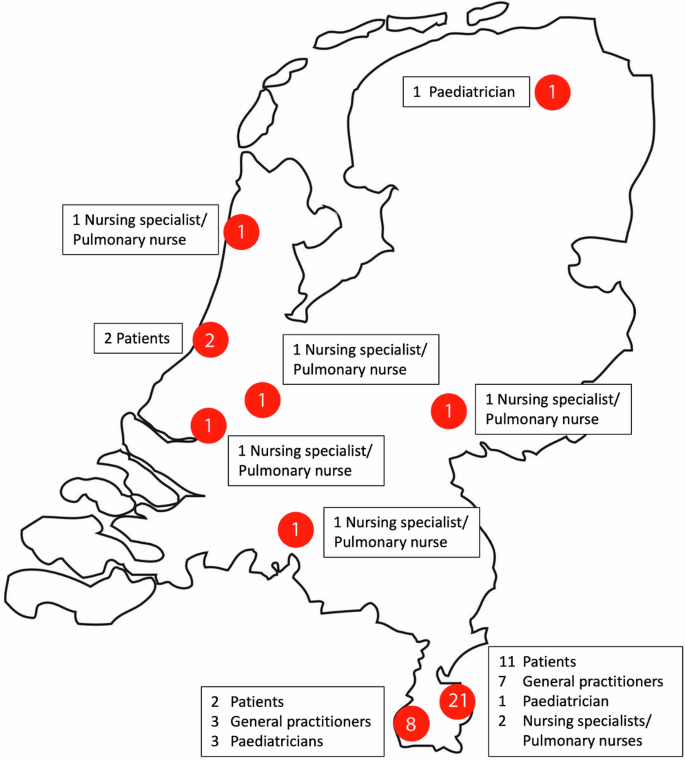

Numbers in red circles indicate the number of participants, broken down into different categories in the text boxes.

General view on current paediatric asthma care

In the context of the demanding clinical workload at GP practices, paediatric asthma management was given limited priority. The reported frequency of asthma care appears low, with only 3–8 paediatric asthma patients per practice, which seems unexpectedly low given the asthma prevalence of 7% in the Netherlands. Considering these are standard practices with an average of 2095 patients per GP in single-handed practices, and the included GPs are part of larger, multi-handed surgeries, one would anticipate a higher number of paediatric asthma cases. The perceived low case frequency may contribute to an oversimplification of asthma care, emphasising acute symptom relief over long-term management. Consequently, treatment is rarely reviewed or tailored, increasing the risk of both over- and undertreatment (Quote 1). While most GPs feel confident managing acute symptoms, some perceive their role as intermediaries when handling cases involving secondary care, often citing a lack of detailed patient information. This creates challenges in continuity of care, as GPs frequently perform initial assessments before referring the child back. Referral strategies vary widely, with some GPs conducting lung function tests while others begin treatment with short-acting beta-agonists (SABA) or corticosteroids without prior diagnostic assessments. Furthermore, practice nurses, integral to primary care, often lack sufficient training to interpret lung function results or implement paediatric asthma guidelines effectively.

Quote 1: ‘I don’t see any problem, the number of known patients is so small. I think I have 3 to 4 patients in my practice, and I am assuming it is going well because I haven’t heard anything from them.’ (GP)

The impact of asthma is often underestimated in both primary and secondary care, with a predominant focus on medical factors and symptom control, while personal and social factors are overlooked. GPs may assume stability if no symptoms are reported, yet patients and parents often misunderstand what controlled asthma entails, normalising issues like frequent coughing and reduced physical activity (Quote 2). Time constraints lead healthcare providers to prioritise medical aspects and inhalation techniques over preventive measures. Awareness of prevention, such as promoting a healthy lifestyle, is limited, with discussions mainly centred on smoking cessation (Quote 3). As a result, treatment heavily focuses on medication, neglecting alternative approaches.

Quote 2: ‘I only see them again when parents report complaints.’ (GP)

Quote 3: ‘To be honest, what falls under prevention? I often don’t have time to address this so it is not on top of mind’ (GP)

Fragmentation and lack of continuity in paediatric asthma care

Parents and children preferred healthcare providers who understand their personal situation. However, the fragmented nature of paediatric asthma care, with multiple healthcare providers, makes it difficult to maintain up-to-date information. This becomes problematic during acute symptoms, as parents feel they must convince healthcare providers of the severity and medical history (Quote 4). Parents who underwent an extensive process before their child stabilised often report receiving conflicting information, which leads to a diminished sense of trust in the healthcare system, particularly in primary care. (Quote 5). In contrast, secondary care is perceived more favourably due to the long-term relationship and deeper insight into asthma management, enabling quicker, more efficient care (Quote 6).

Quote 4: ‘On weekdays, your own general practitioner refers you to the emergency department (ED), and they assist you well there. However, if my child experiences an attack on the weekend or in the evening, and I have to call a different general practitioner, I always find myself having to explain the entire situation and I consider myself fortunate if they provide assistance.’ (Parent)

Quote 5: ‘Then you think, next time, oh well, you know what, I’ll just wait until Monday when we can see our own GP.’ (Parent)

Quote 6: ‘I frequently meet children who I think should have come earlier. For example, children who have been visiting family doctors for too long with only SABA. They then also develop dysfunctional breathing because they constantly have shortness of breath and then it takes quite a while to get them stable again. This can take me up to a year to get this child stable’ (NS)

Due to distrust and lack of structured follow-up in primary care, children are rarely referred back by paediatric pulmonologists (Quote 7). Once referred to secondary care, there is often no review or return referral to primary care, particularly by pulmonary nurses, due to concerns over the quality of primary care. When referred back to primary care, children and parents find themselves in a reactive system, where they must self-report symptoms, despite limited symptom recognition. GP practices also lack the financial structure to support adequate asthma care, including regular follow-ups and sufficient consultation time.

Quote 7: ‘It is not a reproach or anything, because I can understand that we do not yet offer structured care, but there are actually few referrals back. Even the group of children on maintenance medication or allergy medication that is stable remains in secondary care.’ (GP)

Barriers to effective SDM in paediatric asthma care

Healthcare providers understand that SDM is a crucial aspect of forming a strong partnership with patients. The initial reaction from healthcare providers often suggests a belief that they are already practicing SDM effectively. However, only a few, who have deeper knowledge of SDM, acknowledge there is room for improvement (Quote 8). They mention applying SDM primarily for significant decisions rather than minor ones. While providers describe discussing various treatments and deciding together with their patients, further exploration reveals that they often default to seeking informed consent rather than following all the steps of SDM. Additionally, when engaging with children, they do not use specific SDM techniques, aside from addressing children first to help them feel more comfortable. GPs generally felt that SDM practices were integrated into their training. In contrast, paediatricians expressed a desire to implement SDM more systematically but lack a structured approach.

Quote 8: ‘I believe that we have a lot to gain in the area of shared decision-making, especially for relatively simple conditions. We are very aware of it when it comes to major surgeries or decisions regarding resuscitation, but when it comes to something as relatively simple as initiating medication for asthma, we actually do very little.’ (GP)

Most healthcare providers acknowledged the absence of a clear structure or appropriate approach to SDM, particularly in the treatment of children (Quote 9).

Quote 9: ‘Well, the majority of patients don’t express their disagreement at the time of the clinic visit, but then it turns out afterwards that they didn’t actually follow the advice given. If you had asked them at that moment if they supported the decision, would they have honestly admitted their doubts, or is it something that only arises afterwards?’ (NS)

There is a lack of recognition of SDM by parents. When it comes to asthma, parents often adhere to the doctor’s treatment plan without questioning (Quote 10). This is particularly true when dealing with a paediatric pulmonologist, where a significant level of trust is established. SDM could be relevant in the context of medication reduction, particularly concerning the timing of such reductions. It is important to present options that enable SDM, such as providing a treatment plan. Parents are generally satisfied and are not used to forming their own opinions. If they are unaware of alternative options, they tend to accept what they are told. However, there is limited awareness of variation in asthma treatments. Parents often follow treatment plans without questioning or fully understanding the available options.

Quote 10: ‘I just trust and accept it without question. There aren’t many alternatives anyway. However… I have to be honest, there is another, an alternative approach that we haven’t explored at all. It’s really recent, so I want to look into it, but it was never discussed.’ (Parent)

When discussing patient involvement, healthcare providers express more willingness to engage in deeper discussions if patients are informed, even if misconceptions exist (Quote 11).

Quote 11: ‘I am always a bit discouraged by patients who say, ‘Doctor, you decide.’ You never know for sure if they actually follow what you have told them, because they don’t have a strong personal stance on the decision.’ (GP)

A lack of accurate, reliable asthma information remains a significant issue. Patients struggle to find trustworthy online resources, which can lead to misinformation. Healthcare providers, although they refer patients to online resources, encounter difficulties ensuring patients understand and correctly apply the information given during consultations (Quote 12).

Quote 12: ‘After three years, I only learned that coughing was also a symptom, therefore I did not act in a sufficiently adequate way.’ (Parent)

The majority of the interviewed children indicate that they prefer to share their story with the paediatrician/paediatric pulmonologist because they feel that they are being listened to and that the paediatric pulmonologist, given the long treatment relationship, is more aware of the situation (Quote 13).

Quote 13: ‘Some doctors say that I feel good, but I don’t feel good. Then I don’t like her and that’s why I say I want a different doctor.’ (Patient)

Children are often treated as information sources rather than active decision-making partners. Although children are asked to share information, they rarely participate in the decision-making process, with their ability to do so dependent on their reasoning skills. Both parents and doctors may feel apprehensive about involving children in these decisions. Since children are still developing, they require more age-appropriate information to make informed choices (Quote 14-15).

Quote 14: ‘The mother was concerned about the underlying allergy, mentioning that it was diagnosed in the past, and wonders aloud if it is worthwhile to retest. The 9-year-old girl overhears this and realizes that it involves getting a blood test. She expresses her unwillingness to undergo the test. So, on the one hand, we see that she doesn’t want it, but on the other hand, she may not fully comprehend why her mother is considering it and how it could ultimately benefit her.’ (GP)

Quote 15: ‘I think if a child decides everything, those children might not fully grasp all the aspects independently.’ (Paediatrician)

Recommendations for improvement in paediatric asthma care

Overall, general practitioners indicated that they would appreciate more low-threshold contact with secondary care to facilitate interprofessional collaboration. During the evaluation, it was noted that there is a lack of communication from the hospital. GPs express that they would benefit from treatment plans and clear referral instructions. GPs indicate that they experience a communication gap in this respect when it comes to children with asthma (Quote 16).

Quote 16: ‘If you just receive a phone call to alert you, then I immediately refer them to the nurse practitioner in about three months, and they enter the protocolled care. That simply works better than having to recognize this among those 500 letters in a day.’ (GP)

General practitioners expressed that they would benefit from an organised care structure regarding periodic follow-up, so that it would be flagged in their system if a child has not been seen by a healthcare professional. Parents and children were asked about their perspective on remote digital monitoring. Patients indicate that the added value from digital monitoring is primarily seen in understanding the disease and developing self-management skills. A patient in a long-term stable condition mentioned that, currently, they do not perceive the benefits of digital monitoring as they experience minimal symptoms and possess good self-management skills. General practitioners and paediatricians were predominantly positive about digital monitoring and its potential (Quote 17).

Quote 17: ‘Of course, it makes it easier because then I just need to make a call and say, look, this device measures it, take a look. What can I do about it?’ (GP)

Discussion

This study provides critical insights into paediatric asthma care. General practitioners often view asthma care as low complexity and frequency, assuming stability unless patients actively report issues. However, patients and families often lack the knowledge to accurately assess the condition, increasing the risk of acute hospital admissions, over- or underdiagnosis and suboptimal treatment. These findings underscore the need for proactive, standardised, protocol-driven follow-up plans to ensure consistent care. Furthermore, underestimating the chronic impact of asthma on children and families highlights a gap in provider approaches, reinforcing the importance of improved communication to accurately assess patient needs and deliver effective care.

Care fragmentation arises from the differing structures of primary and secondary care, disrupting continuity in diagnosis and symptom management20. Secondary care is proactive, monitoring progress, while primary care is reactive, relying on patient feedback for therapy efficacy21,22. Limited diagnostic resources in primary care, due to the infrequent nature of paediatric asthma, often result in diagnoses based on symptom response, without spirometry confirmation10,11. This misclassification leads to worse dyspnoea perception in undiagnosed children compared to those with a confirmed diagnosis23,24.

The ‘Pulmocheck’ initiative in the province of Limburg offers GPs a one-time hospital consultation for diagnostic evaluation, including spirometry and allergy testing, resulting in high numbers of newly diagnosed asthma and several changes in clinical management17. Despite this initiative and Dutch guidelines recommending regular follow-up, insufficient adherence to these recommendations is linked to organisational and financial constraints in primary care10. The lack of active referrals and follow-up guidance from secondary to primary care reinforces the misconception that asthma is not a significant concern in primary care. Implementing a registry, adequate financial support and comprehensive follow-up advice would address these gaps.

The discussion part above addressed current barriers in the organisation of care, but what are the direct consequences at patient level? A comprehensive Dutch cohort study found that 30% of 8-year-old children who self-reported ‘severe current asthma symptoms’ were not using Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS), indicating possible undertreatment14. Undertreatment can lead to unnecessary symptom burden, reduced asthma control, more exacerbations and irreversible lung damage in the future25. The results show that parents struggle to recognise symptoms, often not knowing what to look for, while GPs only act when symptoms are reported. Consequently, the lack of objective symptom assessment in primary care perpetuates suboptimal asthma control.

In addition, follow-up of children with asthma is essential to ensure proper treatment application, adherence, inhalation technique, and self-management skills. Without regular follow-up, as suggested by the GINA guidelines, these aspects may worsen over time10. As our results show, there is little to no follow-up in primary care. This is evident in a study where 50% of children using ICS for at least 2 years did not report wheezing during that period, indicating possible overtreatment14. Overtreatment can contribute to higher healthcare costs and possible occurrence of side effects. Therefore, regular follow-up is crucial to maintain good asthma control and to prevent over- and undertreatment. A Cochrane review on asthma in adults shows better healthcare outcomes when patients receive regular medical reviews combined with self-management education26,27.

Healthcare providers often have a narrow view of SDM, equating it with listing pros and cons rather than fostering true collaboration. SDM is only effective when both healthcare providers and families are well-informed about the condition’s severity, available options and associated risks and benefits. This goes beyond educating patients; it requires healthcare providers to actively seek and incorporate patient input to understand their experiences, needs and preferences. As this study highlights, the under-recognition of the importance of regular follow-up for asthma signals a need to enhance education and communication for both families and providers. Only by fostering a reciprocal exchange of information can SDM achieve its potential to improve care outcomes. Doctors’ adherence to a positivist paradigm—prioritising a single correct diagnosis and optimal treatment—often hinders SDM implementation28. Encouraging patient activation is vital, as engaged patients improve self-management skills and outcomes29,30. SDM with children adds complexity due to developmental factors and potential parental or provider anxiety31. Yet, evidence links SDM in paediatric asthma to improved quality of life, satisfaction, adherence, fewer healthcare visits and better control32. Despite these benefits, SDM often centres on providers and parents, with children minimally involved33. While children are generally content with adults deciding on treatments, they value being informed, voicing preferences and contributing to decisions about how treatments are administered34.

There is a strong need for standardised assessment on diagnosis and follow-up, aiming to create a more comprehensive care pathway for paediatric asthma. The observed fragmentation in care, inconsistent follow-up advice and suboptimal collaboration between secondary and primary care underscore the urgent need for a structured care pathway. Improved diagnostic processes—such as better access to objective tests like spirometry and allergy testing—are essential for accurate diagnoses and reducing both over- and undertreatment. However, this requires adequate funding, resources and training. As previously described, the initiation of the Pulmocheck initiative in the province of Limburg has led to good results; nevertheless, the low referral rate reflects the challenges of implementing such a care pathway. Regular follow-up can help minimise exacerbations and enhance asthma control, while clear SDM arrangements can significantly improve treatment adherence. This is demonstrated by the results of the Finnish Asthma Program, which is a successful model for improving asthma management and reducing hospitalisations35. Key factors like early diagnosis, effective medication and self-management remain crucial. Integrated agreements result in improved health outcomes, reduced emergency department visits, enhanced healthcare experiences for children and parents and strengthened professional relationships between hospitals and general practitioners for children with non-complex asthma22. It also contributes to better education for general practitioners, emergency department staff and parents regarding asthma management22,36,37.

The main strength of this study lies in integrating diverse perspectives from GPs, children, parents, paediatricians and nursing specialist/pulmonary nurses, enhancing the validity of the findings. The dual-researcher analysis not only bolsters reliability but also validates the coherence of our findings. This approach provided a comprehensive understanding of paediatric asthma care in the Netherlands, with both regional and national representation, ensuring broader applicability. The dual-researcher analysis strengthens the reliability of the results, which are likely generalisable to other European healthcare systems facing similar challenges.

It is crucial to recognise certain limitations. Although interviews provide in-depth insights, they are prone to subjective interpretation. The focus on known asthmatic patients may limit the generalisability of our findings. We cannot completely rule out selection bias, as patient participants were identified by their healthcare providers, possibly favouring those with better doctor-patient relationships. To mitigate this, we encouraged healthcare providers to include patients with varying degrees of engagement and relationship quality. Yet, social desirability effects may have influenced responses despite our assurances of confidentiality.

Our findings have substantial implications for advancing asthma care in the Netherlands, and are applicable/generalisable to similar healthcare systems like the UK. Advocating for standardised follow-up, education on preventive measures and consistent implementation of SDM can contribute to a more holistic approach to care. Recognition of care fragmentation requires improved collaboration between healthcare providers and a structured referral. Policy adjustments are need to incentivize proactive paediatric asthma care in primary care settings.

In conclusion, our study has shed light on the intricacies of paediatric asthma care in the Netherlands, including fragmented care, inadequate follow-up and limited implementation of SDM. Through rigorous methodology, we have uncovered challenges, suggested practical improvements and outlined avenues for future research. These findings contribute to the ongoing dialogue on optimising paediatric asthma management and pave the way for impactful interventions.

Responses