Asthma prescribing trends, inhaler adherence and outcomes: a Real-World Data analysis of a multi-ethnic Asian Asthma population

Introduction

Asthma is a prevalent and costly public health issue, affecting over 260 million people and causing 455,000 deaths worldwide in 20191. Affecting one in 10 adults, asthma costs the Singapore economy USD 1.50 billion every year2. Singapore has one of the highest per capita cost per annum (USD 930), compared to other Asian countries (China: USD 278, Korea: USD 347)2,3,4. Much of the economic burden is contributed by the uncontrolled and severe asthma population2. For instance, uncontrolled severe asthma in Singapore costs almost four times (USD 2235) that of non-severe asthma (USD 636)5.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) monotherapy and -long acting beta 2 agonist (ICS-LABA) combination therapies are the cornerstone therapies for asthma control, exacerbation prevention and mortality reduction6,7. Despite the effectiveness of ICS therapy in asthma control, adherence to ICS has been poor, ranging from 22 to 78% worldwide8. Suboptimal adherence is a major barrier to good asthma control and correlates with adverse outcomes, such as asthma-related mortality, emergency department (ED) visits, inpatient admissions, oral corticosteroid (OCS) use, higher healthcare cost and societal burden9,10,11. Determinants of ICS adherence are complex and multifactorial, comprising patient-, therapy-, disease-related and healthcare system factors8,12,13.

To optimise asthma control at both the individual and population level, we needed to understand the extent of ICS nonadherence, and factors associated with ICS nonadherence. However, we lack real-world studies on multi-ethnic Asian cohorts and most studies were done on Western population with Asian minorities. In a systematic review of asthma inhaler adherence, only three of 51 included studies were based on non-Western populations (including two Japanese studies and one Korean study)13. The previous findings may not be generalisable to Asian asthma cohorts given how different cultural beliefs may influence adherence.11 A cross-sectional study performed in 6 Asian countries (China, Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam) demonstrated that nonadherent patients were twice more likely to perceive herbal medicines as being more effective than the inhalers14. Other gaps were the lack of population-level data as most real-world data (RWD) on ICS adherence were obtained from single healthcare institutions. Also, patients who transitioned between both primary and specialist care have not been studied. To fill these gaps, we performed a RWD analysis of inhaler prescribing pattern, ICS adherence and association with asthma-related outcomes in a multi-ethnic Asian asthma population comprising patients receiving care in both primary and specialist care.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of a multi-ethnic cohort of adult asthma patients (aged ≥18 years) seen in the largest Singapore public healthcare cluster (inclusive of both primary and specialist care settings) between 2015 and 2019. Patient records were retrieved from the SingHealth COPD and Asthma Data Mart (SCDM), an integrated RWD database described previously15. Patients were identified from electronic medical records using the asthma-only codes under the International Classification of Diseases 9: 493 or ICD 10: J45-J4616,17. Patient records included demographics, comorbidities, asthma severity and asthma-related outcomes. Asthma treatment ladder was determined based on the 2015 GINA guideline as the study data collection started in 201518. We extracted asthma-related outcomes including oral corticosteroid (OCS) use and healthcare utilisation, defined by emergency department (ED) visit and hospitalisation with asthma as the final diagnosis. Patients with missing data on covariates, dispensation and prescriptions with missing dosage quantity, frequency or duration were excluded from the study analysis (Supplemental Fig. 1).

We evaluated the temporal trends of ICS and ICS-LABA prescriptions, asthma-related outcomes, and medication adherence pattern between 2015 and 2019. Medication adherence was measured using the medication possession ratio (MPR), based on the ratio of dispensed and prescribed duration obtained from the electronic medication records. To avoid underestimating the MPR, we used the exact prescribed duration instead of an arbitrary duration such as 365 days (adopted in other studies). MPR for each defined interval (in days) as (frac{{sum }_{i=1}^{N}{sum }_{j=1}^{{V}_{i},}{d}_{{ij}}}{{sum }_{i=1}^{N}left[left({t}_{i{V}_{i}}-{t}_{i1}right)+{p}_{i{V}_{i}}right]}) where tij and dij are the time of visit and dispensed duration for visit j by patient i respectively, Vi is the final visit of patient i in the study cohort. pij is the prescribed duration for visit j by patient i. Where dispensed/prescribed duration was unavailable, we derived dij and pij from the total quantity dispensed divided by the total daily dose.

Patients were categorised into good adherence (MPR 0.75–1.2), poor adherence (MPR < 0.75) or medication oversupply (MPR > 1.2)19,20. Excessive SABA dispensing was defined by ≥3 SABA canisters dispensed per year21.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were represented as mean (± standard deviation) and median (interquartile ranges). Temporal trends in inhaler prescription, asthma outcome measures and MPR were evaluated for statistical significance using Poisson regression. Multinomial regression analysis was used to identify associations between medication adherence and the various patient- and clinical-related covariates. The size estimate for each covariate was represented as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses were performed using R Studio, v2022.02.222.

Results

A total of 8023 patients with a mean age of 57.1 ± 18.1 years were reviewed. 56% of the study cohort were Chinese (n = 4459), followed by 22% Malays (n = 1807) and 14% Indian (n = 1120), deviating from our country’s ethnic distribution of Chinese (76%), Malay (15%) and Indian (8%) in 201923. 70% of the cohort (n = 5647) received care from primary care (PC), 13% (n = 1061) received specialist care (SC) while 16% (n = 1315) received both primary and specialist care. 77% (n = 6162) received GINA step 1–3 therapies and 89% (n = 7166) did not have 3 or fewer comorbidities. 69% patients (n = 5552) prescribed ICS were started on metered dose inhaler (MDI) compared to dry powder inhaler (DPI) (Table 1). The 5-year mean MPR for ICS-LABA was lower than that of ICS (0.84 ± 2.80 versus 1.19 ± 1.52) (Table 2). After excluding the patient visits with MPR > 1.2, the 5-year mean MPR for ICS-LABA and ICS were 0.71 ± 0.27 and 0.77 ± 0.28 (Table 2).

Temporal trends in ICS/ICS-LABA prescriptions, SABA overdispensing and asthma-related outcomes

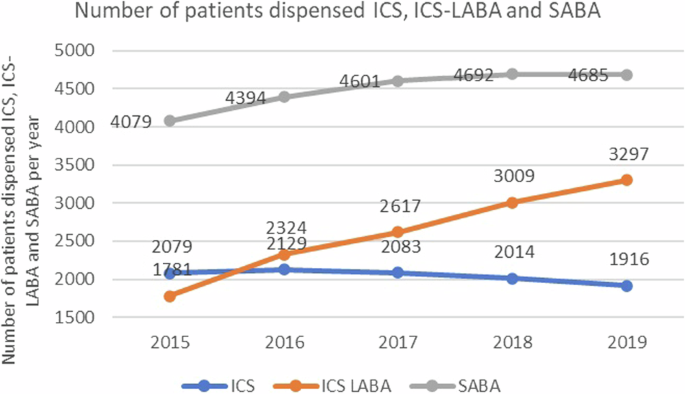

Between 2015 and 2019, 26,423 ICS-LABA and 37,561 ICS-LABA prescriptions were dispensed (Supplemental Fig. 1). The proportion of ICS users decreased from 50% to 36% while that of ICS-LABA users increased from 43% to 61% between 2015 and 2019 (Fig. 1, Table 2). Budesonide/formoterol dry-powdered inhaler (DPI) had the greatest increase in users from 541 (in 2015) to 1107 (in 2019) while Budesonide DPI saw a fall in usage from 479 (in 2015) to 329 patients (in 2019) (Supplemental Table 1). When stratified by site, the proportion of ICS-LABA users in the primary care setting grew from 33% to 52% while the proportion of ICS users decreased from 58% to 43% between 2015 and 2019. In comparison, a smaller increase was noted for ICS-LABA users receiving specialist care, from 79% to 86% (Table 2).

ICS (inhaled corticosteroid), ICS-LABA (inhaled corticosteroid-long-acting beta-2 agonist), SABA (short-acting beta-2 agonist).

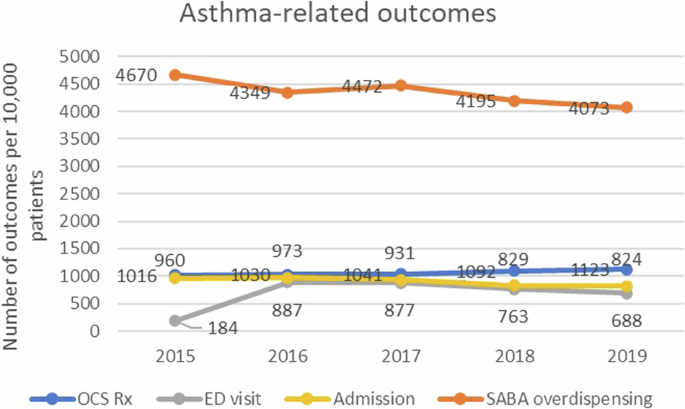

In terms of outcomes, the rate of inpatient admissions decreased from 960 (in 2015) to 824 per 10,000 patients (in 2019) and that of asthma-related ED visits decreased from 887 (in 2016) to 688 per 10,000 patients (in 2019). The rate of OCS prescription remained stable over the years from 1016 (in 2015) to 1123 per 10,000 patients (in 2019), while that of SABA overdispensing decreased from 4670 (in 2015) to 4073 per 10,000 (in 2019) (Fig. 2).

ED (emergency department), OCS (oral corticosteroid), SABA (short-acting beta-2 agonist).

Temporal trends in ICS/ICS-LABA MPR

Between 2015 and 2019, the mean MPR increased from 0.82 to 0.83 (for ICS-LABA) and 0.88 to 0.92 (for ICS) (Table 2), while the proportion of patients with poor adherence decreased from 12.8% to 10.5% (for ICS) and from 30.0% to 26.8% (for ICS-LABA) respectively (Supplemental Table 2). The mean MPR for each year was higher than the 5-year mean MPR due to the exclusion of visits with missing prescribed/dispensed duration (Table 2). Among the ICS-containing inhalers, fluticasone furoate/vilanterol DPI (once daily dosing, costs $31.43) had the highest 5-year mean MPR 0.91 ± 0.17 while fluticasone propionate/salmeterol DPI (twice daily dosing, costs $29.33-70.67) had the lowest mean MPR 0.70 ± 0.26. On the other hand, budesonide DPI (twice daily dosing, costs $46.61) had the greatest MPR 0.81 ± 0.27 among the ICS inhalers while fluticasone propionate MDI (twice daily dosing, costs $32.47–70.43) had the lowest MPR 0.75 ± 0.25 (Supplemental Table 1).

Factors associated with adherence

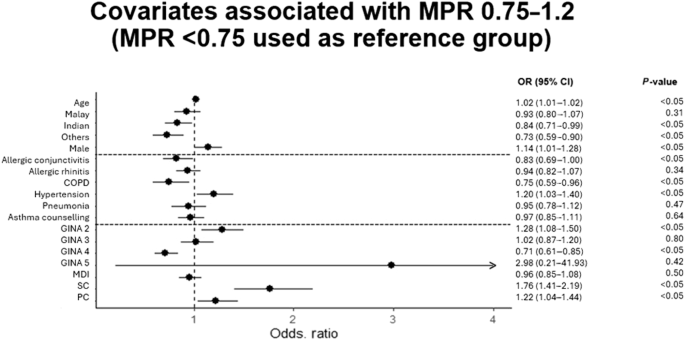

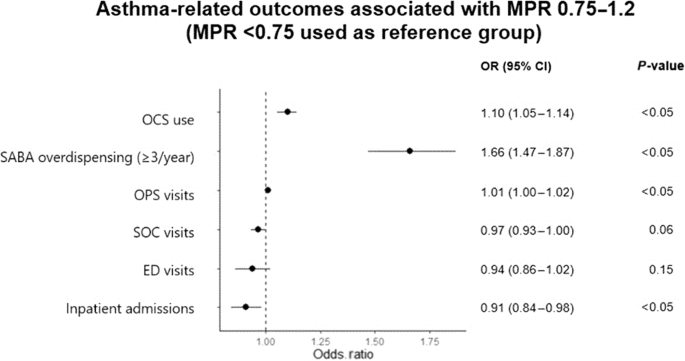

Compared to patients with poor adherence, those with good adherence were more likely to be males (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.01–1.28) and were more likely to attend single site of care (OR 1.22 for PC and OR 1.76 for SC) rather than both, and on GINA step 2 (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.08–1.50) (Fig. 3). Indian and minority ethnic groups (OR 0.73–0.93; compared to Chinese), presence of COPD (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.59–0.96) and GINA step 4 treatment ladder (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61–0.85) were more likely to have poor adherence (Fig. 3). Patients with good adherence were less likely to have inpatient admissions (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84-0.98), more likely to have SABA overdispensing (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.47–1.87) and OCS use (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.05–1.14) (Fig. 4). There was no significant association between ICS formulation (MDI or DPI) and adherence.

CI (confidence interval), COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), MDI (metered-dose inhaler vs. dry-powdered inhaler), PC (primary care), OR (odds ratio), SC (specialist care). Reference groups for race (Chinese), comorbidities (absent), GINA step (step 1), inhaler type (dry-powdered inhaler), SC and PC (both primary and specialist care). Odds ratio for age represents the additional risk for every additional year.

ED (emergency department), OCS (oral corticosteroid), OPS (outpatient primary care service), SABA (short-acting beta-2 agonist), SD (standard deviation), SC (specialist care). Reference group for SABA overdispensing (<3 canisters/year). Odds ratio for OCS use, PC, SC, ED visits and inpatient admissions represents the additional risk for every additional prescription/visit/admission.

Discussion

We observed a rising trend in the ICS-based therapy between 2015 and 2019, consistent with guideline recommendations and changes in policy and funding. In 2019, the GINA guidelines recommended the use of ICS-LABA for step 1 and 2 therapies based on landmark studies showing as-needed ICS-LABA was superior to as-needed SABA when used as rescue therapy (SYGMA1, Novel START) and non-inferiority/superiority to combination regular ICS and as-needed SABA in preventing asthma exacerbations (SYGMA1&2, PRACTICAL, Novel START)6,24,25,26,27. Since the early 2000s, along with the formation of Singapore National Asthma Programme (SNAP), the importance of ICS has been emphasised and ICS use has steadily increased. A previous population study in Singapore showed that ICS use among asthmatic patients almost doubled from 100,700 units to 204,300 units between 1994 and 2002 (p = 0.003), and this correlated with a 30% decrease in both asthma mortality and hospital admission rates (p < 0.005)28. To improve access to ICS-LABA, the Singapore Ministry of Health implemented subsidies for Fluticasone Propionate/Salmeterol MDI/DPI and Budesonide/Formoterol DPI between 2015 and 2016. This initiative could have contributed to the increased guideline-based ICS-LABA prescribing for mild to moderate asthma. In particular, the greatest rise was observed in the primary care and for the prescription of Budesonide/Formoterol DPI, reflecting the adoption of the evidence-based policies and practices25,27.

Similar uptake in ICS/ICS-LABA use has been reported in other populations. In the United States (US), ICS inhalers accounted for 57% of Medicaid expenditure on inhalers, with 168% increment between 2012 and 201829. Specifically, ICS/LABA combination inhalers constituted the greatest spending and growth in expenditure29. These trends were explained by the rise in patients with poorly controlled asthma requiring ICS/LABA therapy and the high costs of branded ICS-LABA inhalers which constituted 97% of the market share29. In the United Kingdom (UK), ICS use in the primary care settings rose from 65% to 80% between 2006 and 2016, preceding the 2016 BTS/SIGN recommendation of early ICS use in mild asthma30. In Scotland, there was a ten-fold increase in ICS-LABA (especially fluticasone propionate/salmeterol) dispensed from 100,000 in 2001 to over 1.5 million in 2017 and a corresponding fall in ICS monotherapy inhalers following national and regional cost-minimisation initiatives such as the BTS/SIGN recommendation31. A recent study of the New Zealand national population prescribing data found that ICS-LABA prescribing (for budesonide/formoterol) increased by 108% between 2019 and 2022, with a 18% reduction in ICS prescribing32. In contrast, a recent RWD analysis of asthma records in Canada showed a decreasing trend in ICS and ICS-LABA use33. The low dispensing rates were attributed to the lack of affordability, inappropriate billing of prescriptions, among other patient-related factors of medication nonadherence33. Consistent with our findings, these RWS demonstrated that prescribing trends in asthma were largely influenced by national initiatives and medication subsidies.

Temporal trends of asthma-related outcomes

Overall, we observed a favourable trend in asthma-related outcomes where the rate of ED visits, hospitalisations and SABA overdispensing fell over the years. These trends reflected the success of the national initiatives in promoting asthma best practices, such as SNAP. Similar improvements in asthma-related outcomes were seen in other countries attributable to better asthma management strategies and primary care, such as the United States where the admission rate decreased from 91.6 to 55.6 per 100,000 people between 2012 and 201734. Beyond 2019, the COVID19 outbreak led to a 50% reduction in the asthma-related healthcare utilisation due to mitigation strategies in reducing COVID-19 transmissions35,36. Post-pandemic, asthma-related healthcare utilisations rebounded due to the relaxation of the pandemic restrictions37. In Singapore, the rate of asthma-related hospitalisation was projected to rise by 1.7% per year, highlighting the importance of understanding the determinants of asthma-related healthcare utilisation35.

The high rates of SABA overdispensing (>40%) observed across our sites of care could be due to excessive prescribing of SABA without clear indication or the increased use of rescue therapy by patients with uncontrolled disease. SABA monotherapy was discouraged since the 2019 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) following evidence of an increased exacerbation rate among SABA monotherapy users6. High SABA dispensing was associated with a dose-dependent increase in exacerbation risk and poorer asthma control; individuals with SABA overdispensing had 30% higher exacerbation risk than those dispensed <3 canisters per year38,39. Our SABA overdispensing rates (40.7–46.7%) are similar to those of other countries, including Canada (46.6–63.2%), US (33.4–46.9%) and UK (51%)39,40. In UK (2013-2017), there was a gradual rise in the ratio of SABA to ICS suggestive of an overreliance on reliever therapy and worsened population-level asthma control41. We observed that patients with good adherence had higher SABA overdispensing rates, which might be related to higher rates of medication dispensing and collection, as opposed to the actual increase in SABA use among this group. SABA overdispensing was also more common among patients attending specialist clinics, which could be due to either the underlying asthma severity of these patients, or the prescribing pattern of healthcare providers in the specialist care. Similarly, a cross-sectional study in Singapore showed that SABA overprescribing was more prevalent in the specialist care than the primary care (26% versus 6%)42. Physicians should prescribe SABA judiciously to reduce waste, environmental and monetary costs and adverse asthma-related outcomes21.

Trends and associations of MPR

The mean MPR for both ICS and ICS-LABA improved with a corresponding decrease in the proportion of patients with poor adherence (MPR < 0.75). Our observed ICS adherence exceeded that of most studies (20–70%), possibly related to the integrated and accessible healthcare model in Singapore43,44. Our healthcare model is based on a copayment scheme, comprising government subsidies and patient’s compulsory medical savings (MediSave)45,46. The national endowment fund (MediFund) finances the medical expenses of eligible low-income patients unable to afford their medical bills45. All public clinics are situated next to a pharmacy where patients can directly fill their prescriptions after the doctor consults.

Patient-, therapy- and disease-related factors

We observed statistically significant inter-ethnic differences in ICS adherence, favoring the Chinese race, similar to previous multi-ethnic studies, where lower adherence rates were observed among the minority ethnicities due to negative beliefs and perceptions towards Western medicines13,47,48,49. A Malaysian cross-sectional study on a multiethnic cohort also demonstrated a higher proportion of well-controlled asthma and better adherence among the Chinese compared to the other ethnicities50. Ethnic-related differences in healthcare utilisation were previously observed in Singapore; a 2000–2003 study by Ng et al. on 1677 asthma patients in Singapore found higher rates of unscheduled clinic and ED visits by the Indians and Malay ethnicities compared to Chinese51. In the Western population, structural racism and the lack of access to social determinants of health (SDOH) were well-established major contributors of health inequity and worse asthma-related outcomes in the minority ethnicities49. For now, it was unclear whether these observed inter-ethnic differences in asthma adherence and outcomes in our multi-ethnic population were contributed by SDOH disparities. Besides ethnicity, female gender was significantly associated with good adherence in our study. However, this was not consistently reported in the literature with an equal number of studies showing better adherence among male patients13.

We did not observe any associations between MPR and the type of inhaler (MDI or DPI). In the systematic review of asthma adherence determinants, the inhaler type was not consistently associated with adherence13. Unlike MDIs, DPIs do not require coordination between dose actuation and inhalation hence are easier to use and have been associated with better adherence52,53. However, the dosing frequency of the inhalers could influence the effect of inhaler type on adherence. One study reported a better adherence with a once-daily mometasone furoate DPI compared to a twice-daily fluticasone furoate MDI which could have been related to the lower dosing frequency of the DPI formulation54. Once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol DPI had the highest MPR among all the ICS-based inhalers in our study. A recent RWS performed on a UK asthma cohort also demonstrated a higher mean proportion of days covered (PDC) with the once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol inhaler compared to the twice-daily budesonide/formoterol and budesonide/formoterol inhalers (77.7% versus 72.4% and 71.0%, p < 0.005)55. Hence, the higher MPR of fluticasone furoate/vilanterol DPI in our study could be contributed by the once-daily dosing frequency rather than the inhaler formulation.

In our study, patients receiving specialist care had the highest mean MPR of ICS-LABA among the three groups. A prospective study by Wu et al. comparing asthma care outcomes by specialists versus generalists also observed better health literacy (69.6% vs. 82.5%) and higher ICS use (66.3% vs. 82.0%) among patients seen by asthma specialists56. Patients managed by specialists were more likely to have an inpatient admission or ED visit (OR 1.59, 95% 1.08–2.35), and had lower quality of asthma care (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.28–0.64) when compared to those managed by experienced generalists56. In contrast, a Canadian RWS on 20,088 patients found a higher rate of ICS-LABA use among the specialist care group (rate ratio 1.43, 95% CI 1.22–1.69) but did not show any significant difference in outcome differences, including mean PDC between the primary and secondary care groups57. Regardless, primary care is pivotal in the asthma management and the asthma outcomes provided by experienced generalists may even outperform those of specialists; in the same prospective study, Close partnership between generalists and specialists is essential for the overall cost-effective management of asthma patients at the population level. Patients who are stable on treatment should be stepped down to the generalists while those with worsening control should be referred back to the specialists for further evaluation and augmentation of therapies58.

A novel finding of our study was that patients receiving both primary and specialist care had worst adherence compared to those receiving a single site of care. The higher rates of poor adherence among these patients suggested either a suboptimal coordination and fragmented care during transition between the primary and specialist care providers in our healthcare system or a mere health-seeking behaviour in this group of patients. Also, patients receiving both primary and specialist care had more comorbidities and poorer disease control compared to those receiving single site of care59. We need to deep-dive into this group, understand and tackle the underlying causes for their worse outcomes, at both the individual and population level.

Finally, disease-related determinants of poor adherence included the presence of COPD overlap and higher GINA steps. Patients with asthma-COPD overlap had poorer adherence than those with asthma only, because of polypharmacy and the extra inhalers prescribed (e.g. long acting muscarinic antagonist inhalers)13,60. Patients with asthma-COPD overlap also have greater healthcare expenditure, hospitalisations and exacerbations61,62. Earlier GINA steps was associated with better adherence and outcomes63. A systematic review on asthma exacerbation concluded that good ICS adherence was associated with fewer inpatient admissions and ED visits (OR 0.32-0.6)63. A study on difficult-to-control asthma reported that medication nonadherence was the only independent predictor of intubation risk, with 1.35 times increased odds of requiring intubation for every 10% decrease in ICS adherence64. However, the association between adherence and control is constantly being challenged, as illustrated by a 12-year cohort study showing how patients with good asthma control subsequently had poorer adherence due to their self-perceived control and down-titration of the controller medications65. Hence, the relationship between adherence and disease-related factors and outcomes must be interpreted in the context of the adherence measure and other confounding factors, such as patient’s health beliefs and self-perception of asthma control.

Strengths

Much of the evidence for asthma therapies were obtained from randomised controlled trials (RCTs)66,67. Given that only 5-10% of the real-world asthma population fulfil RCT inclusion/exclusion criteria, real-world studies using such as clinical registries and databases are essential for cross-validating the RCT findings67. However, the association between adherence and control is constantly being challenged, as illustrated by a 12-year cohort study showing how patients with good asthma control subsequently had poorer adherence due to their self-perceived control and down-titration of the controller medications65. Hence, the relationship between adherence and disease-related factors and outcomes must be interpreted in the context of the adherence measure and other confounding factors, such as patient’s health beliefs and self-perception of asthma control. Real-world studies can address important clinical questions unmet by RCTs, related to healthcare utilisation, epidemiology and treatment adherence2,68. Our use of RWD facilitates the assessment of ICS prescription pattern and adherence in a large population without reporter or interviewer bias15. Our study was also the first population-based RWS on asthma adherence in a multiethnic Asian cohort, and our large study cohort and the inclusion of patients from both primary and specialist care ensure the generalisability of our study estimates. In comparison, Singapore estimates of SABA overdispensing in the SABINA III study were derived from a small sample of 205 patients and differed from our studies (17% versus 40–47%)42.

MPR is the most widely used objective surrogate of medication adherence, used in 53% of the asthma adherence studies on electronic medication records69. Some studies used a fixed denominator (such as 365 days) instead of the study interval, which might underestimate the actual MPR69. In contrast, we calculated the MPR based on the days’ supplied divided by the study interval to obtain a more precise MPR value. In terms of cutoffs, a MPR of 0.75-1.0 represents good adherence as it correlates with a lower risk of asthma exacerbation (OR 0.48-0.68)70,71. We used a higher cutoff of 1.2 as most physicians in our centres would prescribe in slight excess to avoid medication shortage prior to the next visit, and MPR > 1.2 has been cited in previous studies to represent medication wastage72,73,74. Medication oversupply where inhalers are dispensed in excess of the required interval have been associated with worse clinical outcomes, hence were differentiated from good adherence75.

Limitations

A major challenge of using RWD was the duplicate and erroneous entries created during the data mining and processing15. There were several missing variables or disparate values for the same variables, due to inconsistent documentation of the electronic patient records; for instance, the dosage frequency for the specialist clinic was recorded in a different nomenclature from that of the primary care clinics. This led to sample size reduction from 39,319 ICS and 55,182 ICS-LABA prescriptions to 26,423 ICS and 37,561 ICS-LABA prescriptions. In addition, we excluded prescriptions which were not dispensed at all. Hence, this might have overesimated the mean MPR.

A major limitation of MPR was that it does not indicate actual medication use and tends to overestimate the actual adherence especially for medications used on an as-needed basis69. This was evident from the paradoxical association between optimal MPR and SABA overdispensing which was likely due to patients collecting excessive SABA canisters rather than actual SABA overuse. As SABA inhalers lack dose counters, patients are unable to reliably determine the remaining doses and may discard the inhalers prematurely; a study showed that >80% of the salbutamol inhalers discarded by patients were not emptied32. The intrinsic limitation of MPR also led to the overestimated proportions of patients with good adherence when a shorter study duration was used. The 1-year MPR of a frequent defaulter would be greater than the corresponding 5-year MPR due to a smaller denominator used.

We could not study the association of dosage frequency or inhaler type on patient’s adherence due to the variable timing of inhaler switch during the study period. Previous retrospective studies comparing the adherence of different formulations and dosage frequencies either did not account for inhaler switch or terminated the study once the inhaler was changed (which led to variable time intervals for each patient)76,77. Lastly, given the retrospective nature of real-world studies, we could neither confirm the factors determining asthma adherence nor the impact of asthma adherence on the asthma-related outcomes77. Nonetheless, we have identified important prescribing trends and MPR associations for future prospective and implementation studies78.

Conclusion

Locally, we observed a rising trend in the ICS-based therapy between 2015 and 2019, reflecting the success of drug subsidies and evidence-based practices. Overall MPR improved with a fall in poor adherence rates. Asthma-related ED visits and admissions also declined over the years. Patients with better adherence were more likely to attend a single site of care, have higher rates of OCS and SABA dispensing, and fewer inpatient admissions. Factors associated with poor ICS adherence included the non-Chinese ethnicities, presence of COPD and GINA step 4 treatment ladder. SABA overdispensing remains prevalent, highlighting the need to improve awareness and prescribing practices.

Responses