Steady-state dynamics and nonlocal correlations in thermoelectric Cooper pair splitters

Introduction

Leveraging the coupling between the superconducting ground state and spatially separated quantum dots, Cooper pair splitters (CPS) have emerged as viable candidates for generating entanglement in solid-state systems1,2. These devices employ the phenomenon of crossed Andreev reflection (CAR)3, a subgap transport process that occurs between two distinct superconductor-normal (SN) interfaces, to create nonlocal spin-entangled electrons. Recent experiments have reported progress in realizing CPS in numerous systems, including carbon nanotubes4,5, SN heterostructures6,7, semiconducting nanowires8,9,10,11,12, semiconducting13,14,15 and graphene quantum dots16,17,18, to name a few. State-of-the-art techniques such as charge measurement6,7, microwave readout15 and thermoelectric measurements18,19,20,21,22 are employed to probe nonlocal currents arising in CPS devices8,23,24,25,26,27,28.

Coupling a superconducting (SC) region with quantum dots (QDs) at its ends permits the spectral probing of the subgap processes, in which the well-spaced and unbroadened QD levels can act as probes facilitated by electrostatic gating. In addition to the CAR processes, such devices also exhibit competing elastic co-tunneling (ECT) processes between the two QDs, as well as local Andreev reflections (LAR) at each QD2. In particular, a thermoelectric setup eliminates local Andreev processes29 which are generally orders of magnitude larger than nonlocal processes that contribute to the CPS signal. Apart from the CPS configuration, this setup provides a framework for the subgap engineering of CAR and ECT processes in connection with the minimal Kitaev chains for the realization of poor man’s Majoranas30,31,32. In this paper, we theoretically advance the interpretation of the thermoelectric CPS experiment19, not only by giving a detailed explanation of the observed currents, but also by providing new means to establish the nonlocality of the obtained CPS transport signal.

Using the experimental setup19 depicted in Fig. 1(a) as our prototype, we employ the Keldysh non-equilibrium Green’s function (NEGF) framework to unravel new insights into the correlations and transport signals generated in the CPS device. Focusing on the thermoelectric (TE) signal noted in the experiment, we investigate in detail the presence of nonlocal quantum correlations arising at the Cooper pair splitting resonance. Setting up the NEGF approach for the CPS with minimal assumptions, we resolve the currents into the ECT and CAR components, provide vital insights into the spectral structure of the currents and the QD-SC density of states (DOS). We also compute the quantum discord33,34 (see Sect. IV) between the spatially separated QDs to thereby enable us to pin-point the occurrence of nonlocal correlations that are only CAR induced.

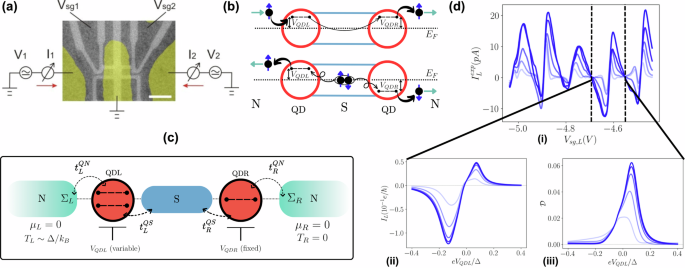

a False colour image of the QD-CPS hybrid device shown to exhibit nonlocal currents under a thermoelectric bias19, with the heater situated on the left side (not shown here). V1, V2, I1, I2 represent the left and right contact voltmeter and ammeters respectively. Vsg1 and Vsg2 are the left and right QD gate-voltages. b A schematic of the ECT (top) and CAR (bottom) mechanisms in the case of un-hybridized QDs, with ECT dominating at the (E, E) resonance and CAR dominating at the (E, − E) resonance. EF denotes the Fermi level of the system. c A detailed schematic of the NEGF-based theoretical model used in this paper consisting of a QD-SC-QD Hamiltonian perturbed by two normal contacts at zero voltage bias potential μL = μR = 0, with QD-N coupling denoted ({t}_{L/R}^{QN}) and QD-S coupling denoted ({t}_{L/R}^{QS}). The left contact is placed under a thermal bias δT ≔ (TL − TR) of order kBδT ~ Δ. The left-dot voltage is varied for analysis. d Analyzing currents through the device as a function of thermal bias. Panel (i) The experimental local TE current (({I}_{L}^{exp}) in pico-Amperes) sweep through the QDL as a function of the left gate bias (Vsg1 corresponding to (c) in Volts) revealing a series of bi-lobe (sawtooth like) current structures for heater voltages Vh ∈ {5, 9, 19, 25, 29}mV whereby the temperature depends on the heater voltage as T ∝ V0.7(see ref. 19). Panel (ii) shows a zoomed-in view of a single current (IL in units of 10−1e/ℏ) bi-lobe structure from our theoretical calculations for kBδT ∈ {0.04, 0.07, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3}. Panel (iii) shows the quantum discord ({mathcal{D}}) between the two QDs computed as a function of VQDL. The color code represents darker colors for increasing temperatures in (i-iii).

Apart from the NEGF technique35,36,37,38, prior theoretical approaches to analyze CPS have been based on semi-classical rate equations39,40, quantum master equations29,41,42,43,44,45, or using a transmission formalism across individual segments19,29 of the device. The master equation approaches are, no doubt, pertinent since the QDs are typically in the Coulomb blockade (CB) regime, such that the charging effects are accounted for within the Fock-space46 of the sub-system. However, in such approaches, the processes of CAR and ECT are accounted for by describing the SC region via effective coupling parameters. Furthermore, in the present experiment19, we will demonstrate that understanding the discreteness of the energy levels, the hybridization effects between the quantum dots, superconducting regions, and contacts, as well as the resulting energy level broadening, is essential to fully explain the observed transport signatures.

Our approach enables a comprehensive insight into the physics of the device without the need to take into account the superconducting segment as an effective coupling41,42 between the QDs. We elucidate the decomposition of the net TE signal into CAR and ECT components, outline the effects of quantum broadening and hybridization, and establish the presence of nonlocal quantum correlations arising at the CPS resonance via the formalism of quantum discord. Thereby, this work provides detailed insights into the gate voltage control of the nonlocal quantum correlations in superconducting-hybrid Cooper pair splitters, revealing new avenues for harnessing quantum correlations in solid-state systems.

Results

Device setup and qualitative reproducibility

A schematic of the setup is shown in Fig. 1b and c. The channel region consists of a one-dimensional superconductor sandwiched between two quantum dots, QDL and QDR. This channel region is tunnel coupled to two normal contacts (N) on the left and right sides. The overall setup Hamiltonian is H = HN + HCh + ∑αHQDα−N, where HCh, HN, and HQDα−N (with α = L, R), represent the channel Hamiltonian, the Hamiltonian of N contacts, and the coupling Hamiltonians between the N region and QDL(R), respectively.

The Hamiltonian of the channel reads, HCh = HS + HQDL + HQDR + HQDL,S + HQDR,S, where HS is the effective 1D SC Hamiltonian

where t0 is the hopping parameter within the tight binding model of the 1D-superconductor (see Supplementary), Δ is the s-wave superconducting pairing potential, μ0 is the electrochemical potential and h. c. is the hermitian conjugate. With a lattice discretization of a = 5nm, we set the length of the superconductor to Ls = 100nm by including 20 sites in the calculation. The hopping potential is then calculated as t0 = ℏ2/(2m*a2) evaluating to t0 = 184meV. The chemical potential is set to μ = 25meV unless otherwise stated. The summation runs over the site (spin) index i(σ). The other components of the channel Hamiltonian, i.e., HQDL + HQDR + HQDL,S + HQDR,S represent the Hamiltonians of the QDL, QDR, the coupling between the QDL, QDR with the SC region. These quantities are defined in detail in the Supplementary.

We denote the energy levels of the left (right) QD by {ϵL(R)}, whose positions are varied via the potentials applied at the local gate electrodes. In accordance with the experiment19, we neglect the Coulomb repulsion, given that there is no clear experimental evidence of Coulomb blockade in the QDs. This is due to the large overlap of the Cooper pair injector with the QDs which results in a tunnel coupling interface with large capacitance. A gate voltage VQDL(R) is applied at the left (right) QD to shift the local energy levels, {ϵL(R) − eVQDL(R)}, where e is the magnitude of the electronic charge. The QDs are coupled with the nearest neighbour SC sites via spin-conserving coupling strengths ({t}_{L(R)}^{QS}), which accounts for the hybridization.

For the N contacts, we consider two semi-infinite normal metallic leads in the site basis (see Supplementary) which are coupled with strengths ({t}_{L(R)}^{QN}) to the left and right QDs respectively. The semi-infinite structure of the leads is accounted for by the self-energies ΣL(R) in the NEGF formalism47 (see Section IV and Supplementary). We represent all relevant quantities in the site (spin) Nambu representation ({hat{psi }}_{i}^{dagger }=(begin{array}{cc}{c}_{iuparrow }^{dagger }&{c}_{idownarrow }end{array})), where elements of any matrix at a given site are in the 2 × 2 electron-hole Nambu space.

We start by noting the experimental trace of the local TE current depicted in Fig. 1(d)(i), which comprises a series of double lobes, and that each double-lobe corresponds to a crossing pair of levels between QDL and QDR. Hereon, we focus on the single TE lobe, and present results pertinent to the essential physics of the CPS operation, rather than a full simulation of the experiment. For this, we include only a single level on both QDs. The right QD level is kept fixed at resonance with the chemical potential, similar to the setup in Fig. 1c.

Figure 1 (d)(ii) shows the theoretically calculated left lead current, which depicts a single sawtooth behavior and a temperature variation consistent with the experimental curves. To identify and verify CAR-dominated parameter regimes, we resort to an information-theoretic quantity exemplifying non-classical correlations known as the quantum discord34. Due to the inherent difficulty of computing entanglement in general mixed states, we utilize quantum discord as a proxy for entanglement generation and apply the recently developed method for calculating discord in fermionic systems33. Informally, the discord is defined as the difference between the total and the purely classical correlations, i.e., non-zero discord implies the quantum nature of correlations (see Section IV and Supplementary Material). We calculate the quantum discord between the opposite spin modes on the left and right dots, as shown in Fig. 1(d)(iii).

Unlike the TE current signal, the discord peaks only at gate voltages coinciding with one of the lobes. As we shall see in more detail, this lobe coinciding with the peak in the discord actually represents CAR contributions to the total current, whereas the ECT dominates the current in the other lobe. The discord thus confirms the presence of a spin-singlet correlation between the two dots in the CAR dominated regions and also showcases the absence of such correlations in ECT dominated regimes.

However, it must be noted that while there could be non-zero mutual information between the same spin σ − σ orbitals of the QDL-QDR, it does not represent any particle entanglement, as it corresponds to correlations of the type (langle {c}_{QDL}^{dagger }{c}_{QDR}rangle). Indeed, we have verified that there is no quantum discord between the σ − σ orbitals throughout the VQDL axis with our calculations (not shown). On the other hand, the discord computed here corresponds to the correlations of the form (langle {c}_{QDL}^{dagger }{c}_{QDR}^{dagger }rangle) and is thus treated as a proxy for steady state entanglement generation via the CPS mechanism.

Resolving CAR and ECT components

To analyze the effects of various parameters on the Cooper pair splitting process, it is necessary to first resolve the TE current signal into its CAR and ECT components. In Fig. 2(a)(i), we plot the TE current for a setup with the SC gap Δ = 1meV, a fixed right-dot gate voltage eVQDR = − 0.1Δ, thermal bias kBT = 0.5Δ and couplings tQN = tQS = 0.02t0. In Fig. 2(a)(ii), We decompose the total TE current into its CAR (solid) and ECT (dashed) components.

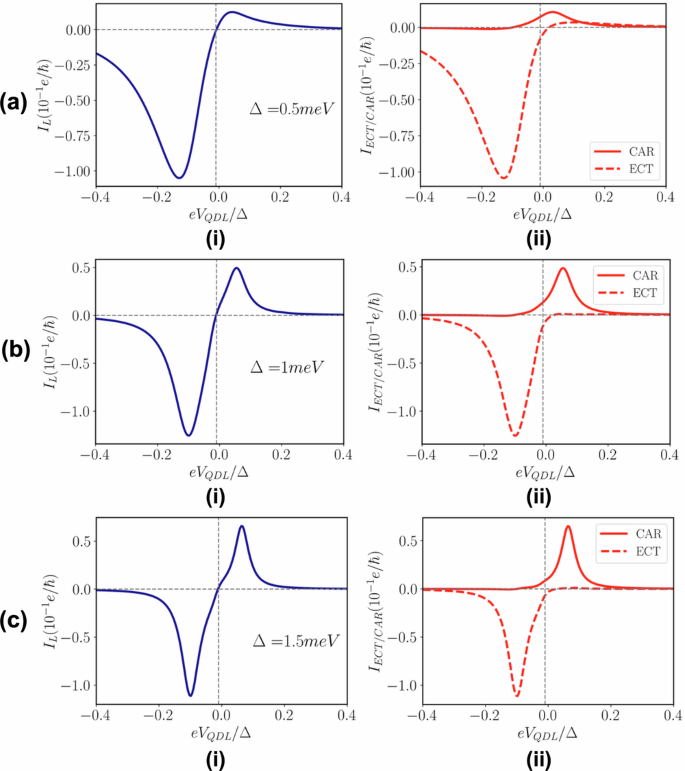

Current profiles across the device structure for (a) Δ = 0.5meV, b Δ = 1meV and c Δ = 1.5meV. (i) Total current through the left contact (IL). (ii) The CAR (ICAR) and ECT (IECT) resolved currents. All the curves involve varying the left dot voltage VQDL with a fixed right dot voltage of eVQDR = − 0.1Δ and a thermal bias of kBδT = 0.5Δ. The chemical potential μ = 25meV, and couplings tQN = tQS = 0.02t0 are held constant as Δ is varied.

These contributions are discernible through the energetics of the underlying subgap transport mechanism. Moving right-to-left along the VQDL axis, when eVQDL ~ − 0.1Δ, the left dot level is effectively at ϵL − eVQDL = 0.1Δ and resonates with the right dot level positioned at ϵR − eVQDR = 0.1Δ, thereby leading to a maximum of the ECT process which is essentially just a direct tunneling process mediated through the suppressed subgap DOS within the SC region. Next, when eVQDL ~ 0.1Δ the left dot level is effectively at ϵL − eVQDL = − 0.1Δ and satisfies ϵL − eVQDL = − (ϵR − eVQDR) = 0.1, at which point the CPS process is assisted by a ready availability of energy levels at E and − E, leading to a peak in the CAR process.

Including the finite SC segment as an integral part of the analysis, rather than adding effective tunnel coupling between the QDs, as done in master equation approaches41, brings to fore many nuances. To further elucidate this, in Fig. 2(a-c), we plot the TE current at the left contact for Δ = 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5meV respectively. Looking at Fig. 1(b), for a given placement of VQDR, one would expect that the ECT resonances will occur at E = eVQDR and the CAR resonance at E = − eVQDR. This is because the ECT resonance occurs because of the spin-conserving tuning process, which takes place when the up- (down-) spin electron (hole) levels align. The CAR resonance occurs at just the opposite energetic condition. We thus note two important subtleties: one, the resonance conditions for the CAR and ECT lobes are not exact as seen by the position of the peaks in Fig. 2(a-c). Secondly, Fig. 2(a)(i), (b)(i), and (c)(i) show that as we increase the order parameter, the CAR component increases, with the ECT component remaining nearly unchanged. Moreover, upon increasing Δ, we note that the CAR peak moves closer to the expected value of eVQDR but the location of the ECT peak remains largely unaltered.

To gain a qualitative difference between the CAR and ECT peaks, albeit being subgap processes that are suppressed exponentially as the SC length exceeds the coherence length48, can be understood from the following insight. We recall that the coherence length is defined as ξS = ℏνf/(πΔ). Noting that the coherence length is inversely proportional to the superconducting order parameter, we can expect that CAR processes become more prominent as Δ increases, which is consistent with many previous studies49,50. To demonstrate this, we vary the coherence length by changing Δ and keeping the length of the superconducting segment (Ls = 0.1μm) constant. In Fig. 2(a)(i), (b)(i) and (c)(i), we set ξS/Ls = 16.3, 8.1 and 5.4 respectively. We see that, although there is only a nuanced effect on the ECT peaks, the CAR peaks improve dramatically as the coherence length becomes comparable to Ls. A naive intuition would be that decreasing Ls would always increase the nonlocal signal; instead, one rather requires ξS ≃ Ls to allow for optimal splitting of the CAR and ECT peaks. Moreover, this effect further elucidates the fundamental difference between the CAR and ECT peaks—while both are indicative of SC-mediated transport between the two quantum dots, the CAR is intrinsically linked to the order parameter Δ, whereas the ECT is related to the quasiparticle tunneling processes that conserve the spin. In the viewpoint of the two spatially separated quantum dots, the ECT appears as a spin-conserving hopping process mediated by the superconducting segment. Understanding the aforementioned subtleties requires a deeper exploration of level broadening and hybridization, which we shall now discuss.

Current spectral decomposition

In the analysis to follow, for our choice of VQDR = − 0.1Δ, the ECT (CAR) resonances occur to the left (right) abscissa axis. We observe in Fig. 2 that the ECT curves are asymmetrically distributed about their resonance, whereas the CAR plots are symmetric. Furthermore, we note that as the SC is strengthened from Fig. 2(a)(ii) to Fig. 2(c)(ii), the asymmetry in the ECT curves is less pronounced. This, we will show, is, in fact, due to the avoided crossings of the ECT process as Δ is varied.

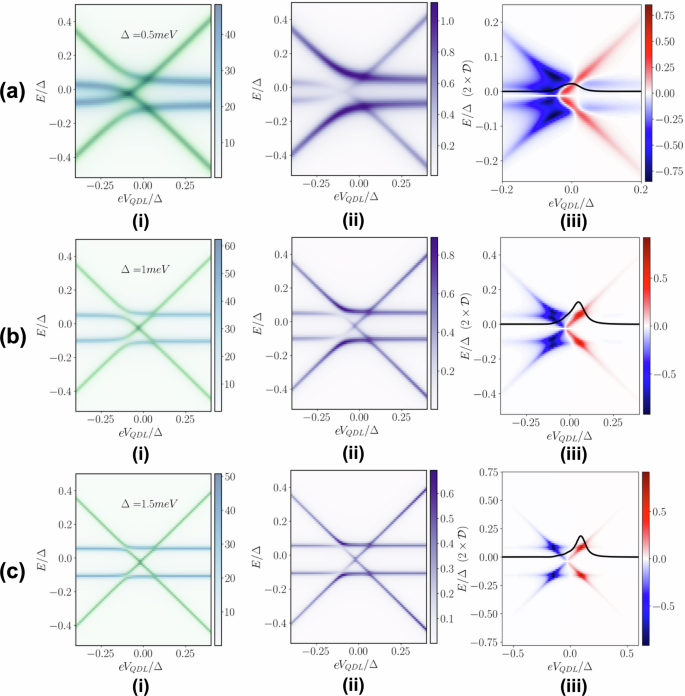

We illustrate this in Fig. 3, where we show (i) the local DOS (LDOS) at the QDs, (ii) the total DOS inside the SC region and (iii) the energy resolved current with discord ({mathcal{D}}) superimposed. All DOS plots are in the units of (frac{1}{Delta }) and current spectra in units of (frac{e}{hslash Delta }). The results are shown for the same set of superconducting strengths as in Fig. 2. As we move from (a) to (c), the Δ increases, the influence of the QDs on the SC segment is minimal, which manifests as a sharper DOS with decreased broadening.

For (a) Δ = 0.5meV, b Δ = 1meV and c Δ = 1.5meV. (i) Superimposed LDOS of QDL (green) and QDR (blue), with the scalebar representing the same maximum intensity. (ii) The DOS of the mediating SC segment. (iii) Energy resolved current spectrum, with the inset curve showing twice the quantum discord ({mathcal{D}}). Parameters are the same as that of Fig. 2. All DOS plots are in the units of (frac{1}{Delta }) and current spectra in units of (frac{e}{hslash Delta }).

The QDL LDOS (green, cross-like) is superposed with the QDR LDOS (blue, horizontal line-like) in Fig. 3(a–c)(i), which shows avoided crossings at both the ECT and CAR points. The avoided crossing represents the states of the QD levels in the presence of the SC, with a larger level repulsion when Δ becomes weaker, indicating a considerable mixing of SC and QD states. This typically happens when the coherence length is large (smaller pairing). Also, such avoided crossings are a generic signature of CAR and ECT processes in a QD-SC-QD setup41 due to two-level atom like transitions between the empty and the singlet states of the two QDs (see Supplementary for further discussion). While the CAR crossing behaves exactly as pointed out in an earlier work41, the ECT crossing shows non-trivial behavior as the Δ becomes stronger, as a direct consequence of contact induced level broadening.

First, we make note that the CAR anticrossings are far less discernible than the ones related to the ECT processes. When we peek into the SC-DOS shown in Fig. 3(iii) column, for the CAR process, we note an equal increase in the QDL and the QDR branches of the SC-DOS. With increasing Δ, the SC segment becomes less influenced by the QD and the CAR magnitude increases with the resonant peak becoming stronger, as noted previously in Fig. 2. This can be clearly seen with the increased contrast of the CAR spectrum as Δ increases. This effect is also illustrated by the sharpening of the discord curve as we move from Fig. 3a–c, further highlighting the strength of information-theoretic quantities like discord. By looking at the energy-resolved conductance spectra of the Δ = 0.5meV and Δ = 1meV cases in Fig. 3(a–b)(iii), it is perhaps difficult to ascertain the nonlocality of the signal obtained. But, the discord computed in the two cases clearly outlines a unique bias point of maximum entanglement generation in Fig. 3(b)(iii). Intuitively, this is owing to the fact that the discord is a highly non-linear function of the density matrix, while the conductance spectra is linear in the density matrix. This suggests that, although the net CAR and ECT signals are accessible, they do not uniquely reveal the QDL voltage point at which the two dots are maximally correlated. In contrast, analyzing the discord offers a clearer insight into this effect. We further clarify this in the next section.

As mentioned earlier, the CAR current magnitude increases49, while the ECT remains largely the same. While the thermoelectric bias depends on Δ, this only affects the currents weakly. Looking carefully at the CAR resonances for the current spectrum along the column Fig. 3(iii), we notice specifically from Fig. 3(a)(iii) that there is a current back flow contribution as noted from the blue striped region. This clearly corresponds to processes that involve mixing of the QD levels with those of the SC, thereby promoting normal reflections in addition to the Andreev processes. This leads to the weakening the CAR leading to a smaller TE current. The CAR processes get stronger with sharper spectral resolution as the Δ is increased, leading to an increase in the total current, which is an integral over the energy axis at a given VQDL.

Detuning the QDR

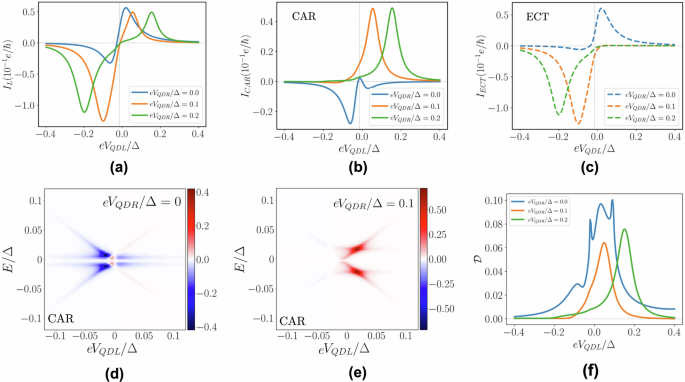

Moving further, we analyze the effects of detuning the right dot with respect to the electrochemical potential of the system. Figure 4(a) demonstrates the TE current through the left lead IL as a function of left dot gate voltage VQDL for eVQDR ∈ {0.0, 0.1, 0.2}Δ. The characteristic saw-tooth widens upon increasing VQDR. Upon resolving the left lead current in Fig. 4(b) and (c), it is clear that the CAR and ECT peaks of the current move away from the resonance point of the hybridised dot level. Upon further inspection of the resolved CAR and ECT currents, we note that for the case of zero detuning, the peaks of CAR and ECT are interchanged, accompanied by a parity crossing in the currents.

a TE current through the left lead IL in units of 0.1e/ℏ. b, c Resolved CAR and ECT currents. d, e Energy resolved CAR current for eVQDR = 0 and eVQDR = 0.1Δ respectively. f Quantum discord for VQDR values corresponding to (a). A comparison between the CAR current spectrum in (d) and (e) clearly shows the flipping of the CAR and ECT lobes with respect to VQDL when VQDR = 0. This is a non-trivial aspect of level broadening due to hybridization of the QD level.

The parity crossing observed in the currents is characteristic to a TE bias when only a temperature gradient applied. The electron and hole currents flip when the chemical potential falls precisely at the mid-gap of a given spectrum. In our case, due to the finite hybridization between either dot and the SC region, this does not happen at the apparent mid-gap symmetry point, which is eVQDR = 0. This can be further elucidated in Fig. 4d–e, where we plot the energy resolved spectrum of the CAR currents for (d) eVQDR/Δ = 0 and (e) eVQDR/Δ = 0.1.

In Fig. 4d, we note two parity changes upon moving from left to right along the VQDL axis and a positive CAR peak on the left side, which moves over to the right side with a single parity crossing upon increasing the detuning to 0.1Δ as in Fig. 4e. Thus, there exists a critical detuning magnitude that is dependent on the SC region and the coupling strengths, after which, the expected behavior sets in for the CAR and ECT peaks. This interchange of the CAR and ECT lobes is crucial to understand when interpreting the experimental current traces.

Lastly, Fig. 4f shows the discord for corresponding VQDR values. While the discord peak moves with the CAR maxima, a critical difference is noted between the eVQDR/Δ = 0 and the eVQDR/Δ ∈ {0.1, 0.2} cases, with the location of the side-peak moving from the left to the right respectively, thereby emphasizing the physics of hybridization due to the contact broadening. We further observe that, for the case of VQDR = 0, the maxima of the CAR and discord curves do not coincide along the VQDL axis. This underscores the importance of analyzing discord along with transport signals. In the pathological case with reversed CAR and ECT peaks, we find that the bias point of maximal quantum discord does not align with the CAR peak. Instead, as shown in Fig. 4b and f, the maximum of the discord corresponds to a local minimum in the CAR curve at VQDL > 0. As we move forward, the expected alignment between the point of maximal entanglement and the CAR peak resumes for eVQDR/Δ ≳ 0.1.

Thus, a combined study of dc-transport signatures and operationally functional information-theoretic quantities, such as quantum discord, enables a comprehensive understanding of the TE sawtooth. This approach provides clear insight into both direct tunneling processes and CPS entanglement generation.

Discussions and inferences

We conducted a detailed analysis of the observed local TE currents19, which revealed crucial insights into the operating regimes and the complex nature of the correlations. The behaviors of the CAR and ECT anti-crossings at different gate voltages highlighted the significant roles of hybridization with the SC segment and level broadening. A detailed current spectral analysis connected these features to the observed transport signals, examining parity reversal and the shifted resonances of the CAR processes. Finally, we established the presence of nonlocal correlations in the CAR current signal through the quantum discord formalism. By interpreting discord as a proxy for entanglement generation, we gained novel insights into the CPS process that could not be obtained through transport signals alone. We believe that the experimental deduction of quantum discord would be an integral next step in determining the nonlocal correlations of the CPS process, and the groundwork for witnessing quantum discord51,52, although in a nascent stage, are already being developed.

Another interesting future direction involves integrating the full spectral information available through our calculations into a time-dependent quantum master equation53 to improve recently proposed driving protocols to maximize CPS efficiency41,42. Furthermore, more precise calculations of the entanglement generation in CPS devices await a quantum trajectory unraveling of the dynamics54. Realizing CPS in two-dimensional topological materials is another promising direction55,56. Additionally, it remains to be seen whether the mechanism of spin-valley locking in certain systems, for example, bilayer graphene or transition-metal dichalcogenide quantum dots, might be used to engineer more precise control over the splitting process in such devices, as well as harness nonlocal valley entanglement.

Methods

We employ the Keldysh-NEGF formalism for the transport calculations. Broadly, it involves calculation of the retarded Green’s function from which the other quantities of interest are derived. The detailed procedures are addressed in the Supplementary Material as well as many recent works47. In the sub-gap transport regime, one evaluates the transmissions for the ECT and the CAR processes, as given by

where, Gr(Ga) is the retarded (advanced) Green’s function, ΓL(R) is the broadening matrix associated with the left (right) contact with the superscripts ee(hh) denoting the electron(hole) sub-sectors in the Nambu representation. The net spectral current at the contacts is a sum of these transmissions weighed appropriately with the Fermi-Dirac distribution differences at the contacts47,

In our study, we apply just a thermal-bias, caused by a temperature difference ΔT = TL − TR, and therefore we set VL = VR = 0, which is precisely why we drop contributions of the Local Andreev processes since they are proportional to the Fermi function difference on the same contact which is exactly zero in the absence of voltage bias. The total current is obtained by integration of the spectral current I(E) over energy. The exact numerical values of NEGF related quantities, such as the number of sites, chemical potential, imaginary damping parameter etc., are provided in detail in our Supplementary Material.

Additionally, to characterize the nonlocal quantum correlations between spatially separated left and right QDs, we employ the formalism of quantum discord34. This quantity is defined as

where S(A: B) is the quantum mutual information between A and B encoding all possible correlations, and I(A: B) is the maximum classical mutual information, maximized over all possible measurements on B. Computing this quantity typically requires an optimization over possible measurements to calculate the maximum classical correlations. However, owing to the fermionic parity-superselection rule, this calculation greatly simplifies33 (see Supplementary Material). The NEGF equations47,56,57 are first solved to get the steady-state behavior of the system at individual energies E, and then a steady-state correlation matrix is computed by integrating electron density lesser Green’s function Gn(E) = − iG<(E) (see the Supplementary for details) along the energy axis, such that

This is a correlator matrix in the Nambu representation with the off-diagonal terms representing the superconducting pairing amplitude. Subsequently, the two-mode occupation-basis density matrix for the up-spin mode of the left QD and the down-spin mode of the right QD is computed using the above steady-state correlation matrix while accounting for correlations within the gap (see Supplemetary Material).

Quantum discord, defined as the difference between the quantum and maximal classical mutual information, is an indicator of quantum correlations between two systems. Following33, we compute the two-orbital fermionic discord between the up-spin orbital of the QDL and the down-spin orbital of the QDR to probe correlations in the CPS (see Supplementary Material).

Responses