Giant tunability of superlattice excitations in chiral Cr1/3TaS2

Introduction

Intercalation is an important strategy for enhancing the functionality of van der Waals solids1,2,3,4,5,6. This is because layered materials such as transition metal dichalcogenides can be endowed with intriguing new properties by filling the van der Waals gap with various ions or molecules, which, in addition to their unique chemistry, break symmetry in new ways. Prominent examples include CuxTiSe2 (x = 0–0.07) which reveals the competition between the density wave state and superconductivity as well as the development of the full superconducting dome7,8,9,10,11, Cr1/3NbS2 and Mn1/3NbS2 which host chiral soliton lattices12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, Co1/3TaS2 which displays skymions in the absence of magnetic field23,24, and even intercalated chalcogenide nanotubes25,26,27. One under-explored aspect of these materials is the properties of the intercalent itself—the extended layer of atoms, ions, or molecules that resides in the two-dimensional potential. In simple systems like FexTaS2 and CrxNbS2, the atomically-thin network of metal atoms forms different patterns within the van der Waals gap depending upon the intercalant concentration (x = 1/4, 1/3)28,29,30,31,32. When incorporated in this manner, the metal monolayers support high-temperature magnetic ordering6,18,19,20,28,33,34,35,36, tunable topological spin textures that interlock with the structure36, complex magnetic field—temperature phase diagrams33,34, unconventional metallicity distinct from that of the parent compound35,37,38,39,40, and superconductivity28,41. The x = 1/3 superlattice pattern is especially interesting because it renders the materials noncentrosymmetric and chiral29. Off-stoichiometric analogs are attracting attention for various charge ordering patterns as well42,43.

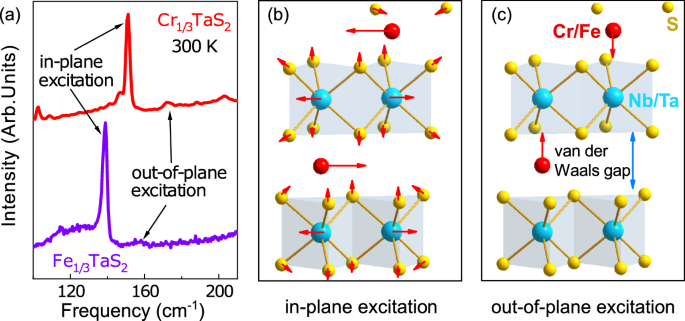

Intercalated chalcogenides host a wide variety of phononic excitations, some of which are quite different than those in standard van der Waals materials. In systems like Fe1/4TaS2, Fe1/3TaS2, and Cr1/3NbS2, the fundamental excitations of the intercalated metal monolayer can be considered as in-and out-of-plane superlattice vibrations that are highly collective in nature [Fig. 1]44,45, although this simplification neglects twisting interaction with sulfur across the van der Waals gap. Here, it’s important to realize that these materials are metallic35,39,40, so infrared-active (odd-symmetry) phonons are screened by the Drude response37,38,39. This is why we explore these features via Raman scattering spectroscopy46. The metal monolayer excitations develop with increasing intercalent concentration45, and when fully formed, they are much stronger and sharper than the fundamental excitations of the chalcogenide lattice44. The in- and out-of-plane features can be distinguished by their resonance frequencies44 and also by their polarizations45. Analysis reveals frequency, lifetime, and intensity trends as well as spin-phonon coupling in terms of the in-plane metal-metal distance, the size of the van der Waals gap, and the mass ratio between the intercalant and the chalcogenide layer44. The extent to which these metal monolayer excitations can be tuned under pressure, strain, or chemical substitution is highly under-explored.

a Close-up view of the superlattice excitations in Cr1/3TaS2 and Fe1/3TaS2. b, c Displacement patterns of the in- and out-of-plane metal monolayer excitations obtained from first-principles calculations44.

In order to investigate the properties of intercalated chalcogenides under external stimuli, we measured the Raman scattering response of Cr1/3TaS2 under compression and compared our findings to the behavior of Cr1/3NbS2, Fe1/3TaS2, and Fe1/4TaS2. The Cr-intercalated materials are significantly more rigid than the Fe-analogs, and the relative lack of pressure-induced symmetry breaking allows the metal monolayer excitations to shift in a nearly linear fashion across important portions of the teraHertz regime. As a specific example, pressure hardens the 150 cm−1 in-plane metal monolayer excitation in Cr1/3TaS2 by about 15% whereas strain softens the same excitation by about 1%. Total tunability is on the order of 16%. A relatively narrow van der Waals gap supports this behavior. This work opens the door to pressure and strain control of spintronics devices47,48,49,50,51,52,53, tunable THz resonators for LiDAR applications44, and a greater understanding of structure–property trends2,6 in this family of intercalated chalcogenides.

Results and discussion

Cr1/3TaS2 under pressure

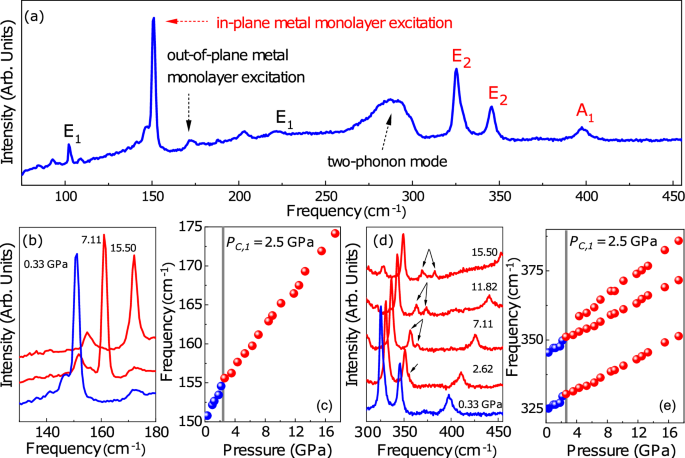

Figure 2 summarizes the Raman scattering response of Cr1/3TaS2 under compression at 300 K. The intercalated metal monolayer excitations and the symmetries of the intra-layer phonons are labeled44. Our focus in this work is on the behavior of the in-plane metal monolayer excitation at 150 cm−1. This feature is exceptionally sharp and strong—even more intense than the fundamental excitations of the chalcogenide layers – suggesting that the Cr centers are well-ordered and sit properly on a (sqrt{3}times sqrt{3}) lattice [Fig. S5, Suppplementary information]. We estimate a phonon lifetime τph (from the linewidth) of 4.7 ps, which is unusually long54,55. As a reminder, Cr1/3TaS2 is chiral and non-centrosymmetric due to the x = 1/3 concentration of A-site ions and their hexagonal pattern in the van der Waals gap—just like Fe1/3TaS26,29. This pair of materials allows us to compare the role of A site chemistry and size (Cr vs. Fe) while retaining the same TaS2 chalcogenide layer [Table 1].

a Raman scattering response of Cr1/3TaS2 at ambient conditions along with the mode assignments. b, c Close-up view of the metal monolayer excitation under pressure + frequency vs. pressure trends for this feature. The color is indicative of the phase. d, e Close-up view of higher frequency chalcogen-related modes + frequency vs. pressure trends.

In general, pressure will change bond lengths and angles and, at the same time, systematically reduce the van der Waals distance and modify the structural c/a ratio30,56,57,58. Cr1/3TaS2 is no exception, and the majority of spectral features harden under pressure. Remarkably, even 15 GPa does not significantly distort the 150 cm−1 in-plane metal monolayer excitation. There is a small kink in the frequency vs. pressure plot near 2.5 GPa consistent with a change in metal…sulfur interactions, although there is no modification to the hexagonal pattern of the intercalated Cr centers within our sensitivity. The line width of the metal monolayer excitation also broadens with increasing pressure [Fig. 2b], indicating a decrease in the phonon lifetime (from 4.7 ps at ambient conditions to 1.9 ps at 15.5 GPa). The in-plane E2 symmetry mode of the chalcogenide layer near 342 cm−1 also splits into a doublet under compression. The location at which it does so is in good agreement with the aforementioned kink in the frequency vs. pressure plot of the metal monolayer mode. Taken together, the kink and the doublet splitting define a critical pressure of PC,1 = 2.5 GPa, although the structural distortion is (i) weak and (ii) resides primarily in the chalcogen layers. As a result, it does not strongly impact the overall linear response of the metal monolayer excitation under pressure. Our calculations (detailed below) reveal that the E2 symmetry mode near 340 cm−1 breaks symmetry due to an asymmetric distortion of the hexagons in the chalcogenide layer. Increased pressure thus reduces the space group of Cr1/3TaS2 from P63/22 → P321.

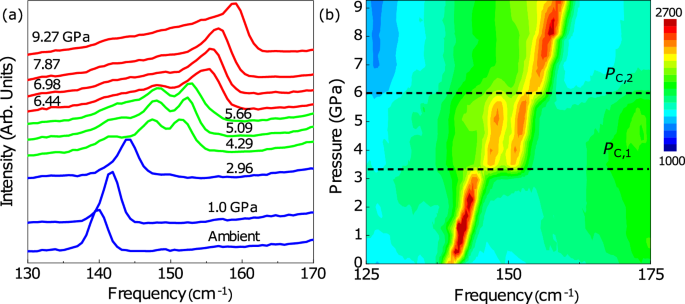

By way of comparison, Fe1/3TaS2 is significantly more flexible with pressure-driven transitions at PC,1 = 3.3 GPa and PC,2 = 6.0 GPa, respectively [Fig. 3]. These structural phase transitions involve the chalcogenide layers and the metal monolayers, separating the P63/22, mixed phase, and high-pressure phases. Analysis of the frequency shifts, splittings, and symmetry restorations provides information about the space group of the high-pressure monoclinic phase which will be discussed elsewhere, although this time, the high-pressure group appears to be P3. Key to our discussion below is that the in-plane metal monolayer excitations harden systematically until approximately 3 GPa. Above PC,1, the excitation broadens considerably and then splits—a signal of the mixed phase.

a Close-up view of the in-plane metal monolayer mode of Fe1/3TaS2 under compression at 300 K. b Contour plot of the same data. The critical pressures are indicated.

At first glance, the difference between these two materials is surprising, so it is important to examine the numbers. The masses on the A-site are similar (55.845 vs. 51.996 amu for Fe and Cr, respectively), but the ionic radii are less so (0.780 vs. 0.615 Å) [Table 1]. It appears that, given a van der Waals gap within which to move, the Cr centers are less likely to distort. The van der Waals gap itself is also significantly smaller in Cr1/3TaS2 compared with the Fe analog (2.989 vs. 3.071 Å). Our prior work reveals that pressure-induced structural distortions involving the metal centers in intercalated chalcogenides are blocked when the van der Waals gap becomes too small, or the A-site ion becomes too large44. Thus, physical and “chemical” pressure yield similar trends in these materials.

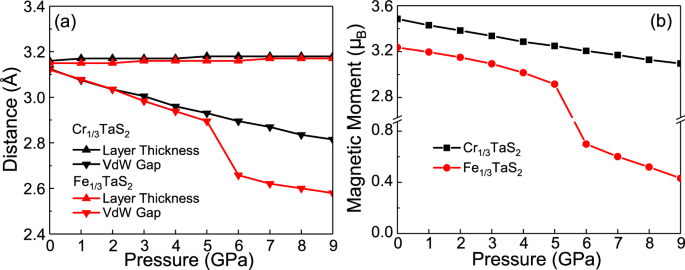

In order to better understand the role of metal site substitution in triggering (or blocking) pressure-driven structural transitions, we performed complementary first-principles calculations to reveal specific differences between the Cr and Fe analogs. Overall, we find that the van der Waals gap decreases significantly under compression, whereas layer thickness is actually predicted to increase very slightly with pressure59. This explains why the metal monolayer modes are so strongly affected by pressure (more than the layer modes) in these systems. In any case, we find that the metal monolayer mode in Cr1/3TaS2 hardens linearly under pressure, consistent with our experimental findings. It doesn’t matter whether our calculations are constrained or not; the properties change smoothly under compression. Fe1/3TaS2 is different. As shown in Fig. 4a, our calculations predict a structural phase transition near 6 GPa due to c/a effects. Additionally, this dramatic decrease in the van der Waals gap appears to take place with a reduction in the Fe magnetic moment. As shown in Fig. 4b, the moment drops sharply across the transition, consistent with high spin S = 3/2 to low spin S = 1/2. Since the calculations do not stabilize mixed states, this should be regarded as being in excellent agreement with our experiments.

Density functional theory comparison of a layer thickness and van der Waals gap versus pressure for both Cr1/3TaS2 and Fe1/3TaS2 and b magnetic moment as a function of pressure for both materials.

Cr1/3TaS2 under tensile strain

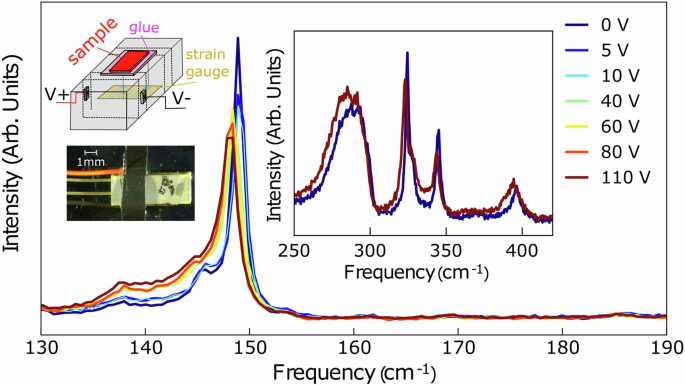

Given the systematic frequency shift of the in-plane metal monolayer excitation under pressure, we decided to test whether this excitation responds to strain. As shown in Fig. 5, this feature, as well as the many chalcogen layer modes soften under tensile strain. Obviously, the strain applied is small, on the order of 3%, which is sufficient to observe the softening trend but insufficient to induce a phase transition. We find that the superlattice excitation in Cr1/3TaS2 hardens almost linearly under compression and softens linearly under elongation. Going forward, it will be interesting to explore how a softer lattice under strain impacts surface spin wave motion and tunable color properties in this system32. Applications in the area of antiferromagnetic spintronics may benefit from structural tunability as well47,48,49,50,51.

Close-up view of the Raman scattering response of Cr1/3TaS2 as a function of strain at room temperature, focusing on the behavior of the metal monolayer excitation. 100 V corresponds to approximately 3% strain. The insets on the left show a schematic of the piezostack, which operates under voltage control as well as an image of our crystal on the piezostack. The right-hand inset shows that the chalcogen layer phonons soften under tensile strain.

Tunable THz resonators from natural superlattices

One of the most fascinating aspects of the metal monolayer excitations in this family of intercalated chalcogenides is their intensity. In fact, the intensities of these highly collective modes are even stronger than the fundamental A and E symmetry phonons of the chalcogenide lattices. The line widths are narrow as well. This suggests that metal monolayer excitations might be able to act as tunable teraHertz resonators, perhaps for ultra-fine sensing and flash LiDAR detection44,52,60,61,62 or even as tips themselves53. Figure S5 in the Supplemental information shows a close-up view of the superlattice excitations in the materials of interest here. The main point is that by judicious choice of the intercalant (including the use of 4- and 5d ions), it is possible to position the resonance at different points across the teraHertz range. Small pressures and strains can then be used to refine the position of the collective excitation.

The pressure trends in these materials are interesting and not at all identical. Of the many members of this family of materials that we have studied, Cr1/3TaS2 is likely to be the most useful due to the nearly linear blueshift of the resonance frequency under compression and the relative lack of pressure-driven local lattice distortions. In our hands, the position of the in-plane metal monolayer excitation in Cr1/3TaS2 hardens systematically from 150 to 172 cm−1 under 15.5 GPa. This is a frequency shift of nearly 15%. The teraHertz resonance in Cr1/3NbS2 is tunable as well, although slightly less linear, moving from 194 to 209 cm−1 over 7.5 GPa—a frequency shift of 10%. As discussed previously, we also tested the ability of the strain to control the position of the in-plane metal monolayer excitation in Cr1/3TaS2 [Fig. 5]. Under modest strain, this excitation softens by 1.5 cm−1 (approximately 1%). The total tunability in Cr1/3TaS2 is approximately 16%. We, therefore, see that pressure and strain have the potential to both harden and soften the position of the collective excitation. Whether similar tunability can be anticipated for other materials of this type is still an open question. Fe1/4TaS2 and Fe1/3TaS2, for instance, break symmetry at relatively low pressures. They consequently have a very limited range with a linear response [Fig. 5b and Table S1, Supplementary Information]. By comparison, Cr1/3TaS2 and Cr1/3NbS2 host teraHertz resonances that respond almost linearly under pressure. Taken together, these materials set the stage for the development of a very flexible set of THz resonators.

Discussion

Thus far, we have combined Raman scattering spectroscopy with diamond anvil cell techniques and complementary first-principles calculations to explore the low-frequency excitations of a series of natural superlattices in the form of intercalated chalcogenides. Each material hosts in- and out-of-plane excitations of the intercalated metal monolayer that resonates in the teraHertz range. The exact resonance frequency of these collective excitations depends upon the chemical identity and loading of the intercalent. In principle, the resonance frequency can be tuned across much of the useful teraHertz range in this manner. Pressure and strain are useful external stimuli in certain cases as well. We find that while the metal monolayer excitations in FexTaS2 (x = 1/4, 1/3) distort significantly under compression, the same excitation in related systems, including Cr1/3TaS2 and Cr1/3NbS2 shifts almost linearly under pressure and strain. We discuss these trends in terms of the chalcogen layer thickness and size of the van der Waals gap compared to the size of the A site ion. These structure–property relations, along with the linear responsivity of the teraHertz resonance under pressure and strain, pave the way for various spintronics and photonics applications.

Methods

Crystal growth and loading of the diamond anvil cell

High-quality single crystals of several different intercalated transition metal dichalcogenides were grown via flux techniques as described previously29. The concentration of Cr was determined using a combination of energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) and the saturated magnetic moment obtained from measurements of the magnetic moment as a function of the magnetic field (M–H) at 2 K. We selected Cr1/3TaS2, Cr1/3NbS2, Fe1/3TaS2, and Fe1/4TaS2 in order to explore structure-property relations in this family of materials. That said, the majority of work focuses on Cr1/3TaS2 and Cr1/3NbS2, with only brief comparisons to the Fe analogs. Small, well-shaped pieces of each crystal were selected and loaded into suitably chosen diamond anvil cells with either KBr as the pressure medium to ensure quasi-hydrostatic pressure conditions [Fig. S1, Supplemental information]. An annealed ruby ball was included to determine pressure via fluorescence [Fig. S2, Supplemental information]63,64. Two different symmetric diamond anvil cells were used in this work. Both employed synthetic high temperature-high pressure type II as low fluorescence diamonds with either 500 or 600 μm culets. These measurements employed 50 μm thick pre-indented stainless steel gaskets with 200 μm diameter holes.

Raman scattering under pressure

We performed Raman scattering measurements (10–600 cm−1) using a 532 nm (green) laser with 3.5 mW power, a triple monochromator, and a liquid nitrogen-cooled CCD detector. Scans were between 30 and 60 s, averaged 5 or 10 times depending on the need. The pressure was increased between 0 and approximately 11 GPa at room temperature. We monitored the shape of the ruby fluorescence spectrum before each measurement to ensure that the sample remained in a quasi-hydrostatic environment. We compare the Raman scattering spectra of pristine and pressure-cycled Cr1/3TaS2 in Figs. S3 and S4, Supplemental information.

Raman scattering under strain

To complement high-pressure work in the diamond anvil cell, we also performed Raman scattering spectroscopy under strain on selected samples. Piezostacks operating under voltage control provide access to both compressive and elongational strain effects [inset, Fig. 4]. It is very important to use thin crystals (less than 10 μm) so that strain remains uniform across the sample. Strain is linearly proportional to the voltage. We calibrate the relationship between applied voltage and strain using distance markers as described elsewhere32. In our case, 100 V is equivalent to approximately 3% tensile strain.

First-principles calculations

To understand the change in the structural and magnetic properties, density functional calculations were performed using QuantumATK within a spin-polarized generalized gradient approximation (SGGA), a Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation, and a PseudoDojo pseudopotential65,66,67,68. The calculations were run with a Grimme DFT-D3 van der Waals correction69. Structures were geometry optimized to a maximum force of 0.01 Å/eV and applied constrained and unconstrained isotropic pressure from 0 to 9 GPa. The calculations used a k-point sampling of 6 × 6 × 3 with a tolerance of 10−5 Hartrees.

Responses