Electronic spin susceptibility in metallic strontium titanate

Introduction

Strontium titanate (SrTiO3, STO) is one of the most extensively studied quantum materials and exhibits a host of fascinating properties that remain heavily debated1,2. Pristine STO is a band insulator that is very close to a ferroelectric instability: it features polar phonon modes that soften dramatically upon cooling, but do not condense to form long-range ferroelectric order3. This causes a large low-temperature dielectric permittivity1 and a strongly nonlinear response to electric fields4. Moreover, when charge carriers are introduced, the system undergoes an insulator-metal transition at extremely low carrier densities5,6,7,8 due to the large electronic Bohr radius induced by the high lattice polarizability. Despite extensive experimental and theoretical efforts, the salient features of this low-density metal are not understood. In particular, key questions regarding the nature of the normal-state charge carriers9,10,11,12 and the electron-phonon interaction in STO and related materials1 remain open.

While it is known that the dilute metallic state of STO exhibits sharp Fermi surfaces at low temperatures6,7,8, electrical resistivity measurements have revealed an extended Fermi-liquid-like temperature dependence that cannot be explained by conventional electronic scattering mechanisms10. Optical spectroscopy12,13 and transport measurements11 have provided evidence of highly unusual behavior of the carrier effective mass, which appears to increase significantly with temperature. In addition, the formation of the low-temperature superconducting state is still controversial, six decades after its discovery2,14. It is likely that the coupling of electrons to the soft polar phonon modes plays a pivotal role2,15,16,17,18,19,20; however, the conventional lowest-order coupling that is linear in the phonon amplitudes is forbidden by symmetry. Several alternative coupling mechanisms have thus been proposed, including two-phonon processes21,22,23,24 and a Rashba-like spin-orbit-assisted interaction25,26,27,28,29,30. Yet the influence of electron-phonon coupling on charge transport is the subject of debate23,31, and the extent of polaronic effects on the charge carriers remains unclear. Moreover, a similar low-density metallic state appears in a diverse group of materials systems1,32,33,34, including thin films and heterostructures35,36,37,38. It is thus of fundamental importance to obtain microscopic understanding.

Here we use nuclear magnetic resonance to gather insight into the nature of the metallic state of STO. While NMR results have been reported for undoped, insulating STO39,40, metallic compositions have not been systematically studied with this bulk local probe. We use the Knight shift of titanium nuclei to determine the temperature and carrier concentration dependence of the local electronic spin susceptibility and compare the results to detailed calculations that take into account the multi-band structure of STO. Throughout the phase diagram, we find that the behavior of the spin susceptibility corresponds to a Fermi gas with low degeneracy temperatures and a temperature- and doping-independent effective mass that is only moderately (a factor of two) enhanced compared to the noninteracting case. These results clarify the nature of the charge carriers and establish a basis for the understanding of the electronic behavior in STO and related materials with soft polar phonons, such as KTaO3 (KTO).

Results

Spectra and spin-lattice relaxation

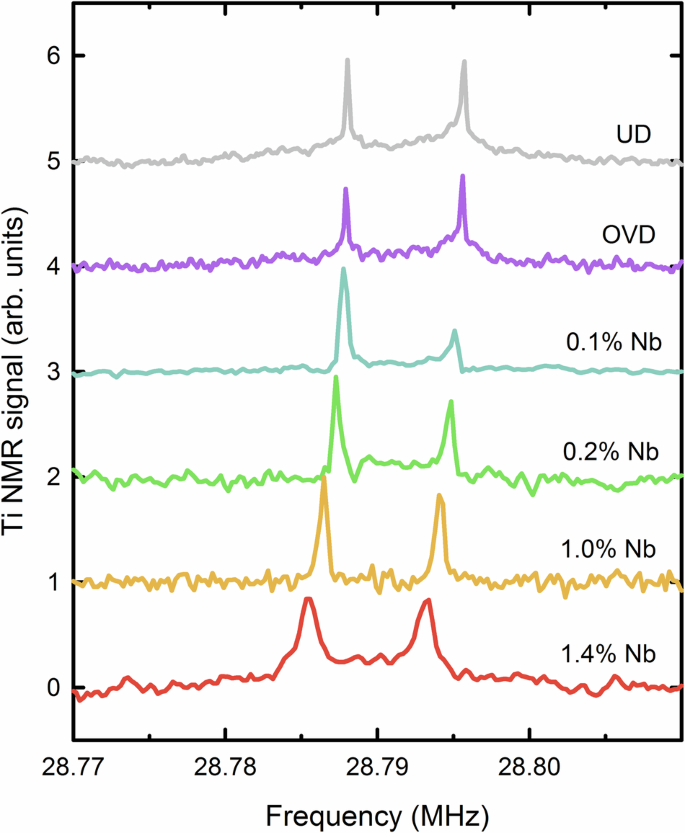

Representative ambient-temperature NMR spectra of metallic STO samples are displayed in Fig. 1. Both titanium isotopes, 47Ti (spin 5/2) and 49Ti (spin 7/2) are visible, and the doping-induced changes of the resonant frequencies (Knight shifts) are directly related to the electronic spin susceptibility through the well-known linear relation

where K is the Knight shift, Ahf the hyperfine coupling constant, and χ(q → 0) the static spin susceptibility in the limit of zero wavevector, which is appropriate for titanium nuclei in the cubic perovskite structure. The broadening of the lines is most likely caused by the coupling of the titanium nuclear quadrupolar moments to local electric field gradients induced by deviations from the average cubic structure in the vicinity of dopant atoms. Yet the NMR lines remain very narrow up to the highest studied doping level, and the Knight shifts do not exceed a few kHz. The electronic susceptibility is thus clearly small, and it would be exceedingly difficult to reliably extract it from bulk magnetization measurements, given their sensitivity to even tiny concentrations of paramagnetic impurities. As a bulk-sensitive local probe, NMR is therefore uniquely positioned to determine the spin susceptibility in low-density metals such as STO. 47Ti spectra in a wide temperature range are shown in the Supplementary Information (Figs. S1–S3); notably, we do not observe systematic changes of the linewidth at the cubic-to-tetragonal transition at 105 K, which suggests that the associated atomic displacements and disorder due to tetragonal domain walls are too small to significantly affect the titanium nuclei. We therefore ignore quadrupolar effects and assume that the shift is entirely caused by hyperfine coupling of the nuclei to delocalized charge carriers.

UD and OVD denote undoped and oxygen-vacancy doped samples, respectively, while the niobium concentration (atomic %) is denoted for Nb-substituted samples. The lower- and higher-frequency peaks correspond to the isotopes 47Ti and 49Ti, respectively. The signals are normalized to the values at the low-frequency peaks; the noise levels differ because of varying sample sizes and electromagnetic penetration depths.

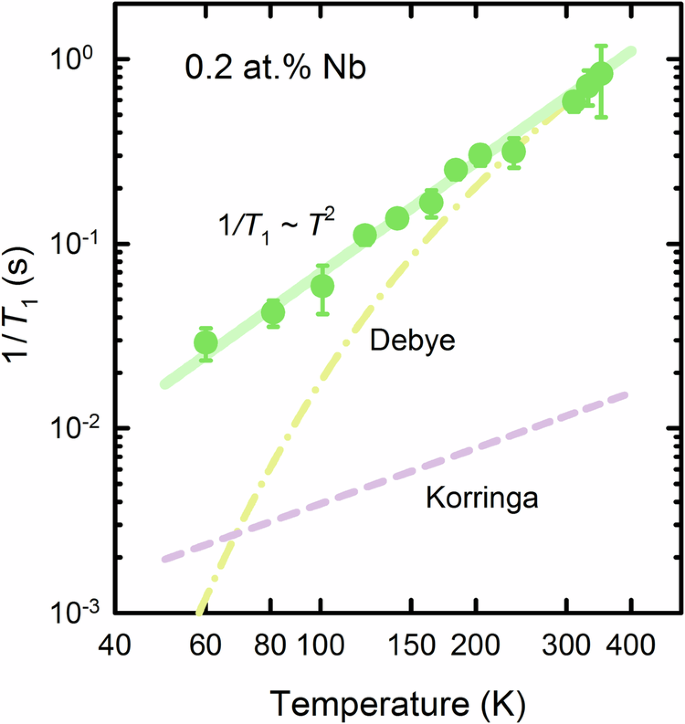

In contrast, we find that spin-lattice relaxation predominantly originates from a coupling of the nuclear spin system to phonons. Phonons can couple dynamically to the titanium nuclear spins via the 47,49Ti quadrupolar moments, with a known coupling constant that depends on both spin and quadrupolar moment values (see “Methods”). For a purely quadrupolar coupling, the predicted ratio of spin-lattice relaxation times for 49Ti and 47Ti is 3.5, which matches well with the experimental value of 4 ± 1 obtained at 330 K (see Supplementary Information for raw data). Furthermore, the relaxation mechanism is consistent with a Raman phonon process41, with a characteristic temperature dependence of the form 1/T1 ~ T2, where T1 is the relaxation time and T the temperature (Fig. 2). Although the low signal intensity and long relaxation times preclude more detailed measurements at temperatures below around 50 K, we note that very similar behavior is also found in undoped KTO42, which provides further evidence for the absence of electronic effects in 1/T1. However, a standard Debye-model calculation of the Raman phonon process shows that acoustic phonons yield a T2 relaxation above the Debye temperature41, while the dependence becomes ~T9 significantly below the Debye temperature. Since the latter is around 550 K in STO43, the Debye model cannot explain the observed temperature dependence. In order to make this point more explicit, we compare the data to a calculation of the Raman phonon process within the Debye model (dash-dotted line in Fig. 2; see also “Methods” for details), which clearly underestimates the relaxation rate at lower temperatures. Therefore, soft phonon modes probably play an important role in the relaxation mechanism. Coupling of the nuclear spin system to the soft transverse optic (TO) phonon also yields a T2 contribution for kBT ≫ ℏωTO, where ωTO is the phonon frequency at the Γ point44. In undoped STO, ℏωTO ~ 1 meV ~ 10 K/kB at the lowest temperatures, but the phonon frequency increases quite strongly with both temperature and doping. Furthermore, hybridization between the transverse optic and acoustic (TA) modes leads to a softening of the latter close to the zone center, with an associated increase of the phonon density of states, in both undoped STO and KTO45,46. A Raman process that involves the soft TO and TA modes is thus the most likely origin of the observed behavior. As noted, the TO phonon energy increases with carrier concentration, with an associated weakening of the TO-TA hybridization47. Our observation of a clear T2 dependence indicates that the local nuclear spin relaxation time is insensitive to these changes in the 0.2% Nb-substituted material, at least within the studied temperature range. The effects of the electronic renormalization of the phonon spectrum would likely be more clearly visible at even lower temperatures and/or higher carrier concentrations, and this could be an interesting avenue for further, more detailed study.

Similar to insulating KTO42, the behavior is consistent with T1 ~ 1/T2 (full line). The electronic contribution estimated from the low-temperature Knight shift (see Fig. 3) using the standard Korringa relation is plotted as a dashed line. The inconsistency of the latter with experiment indicates that two-phonon Raman scattering dominates over electronic relaxation in the entire temperature range. The predicted two-phonon temperature dependence (see “Methods”) for a simple Debye model of the phonon system is plotted as a dash-dotted line. The significant discrepancy at low temperatures suggests that soft phonon branches play an important role, as also seen in specific heat measurements43.

We also compare the experimental result to an estimate of the expected electronic contribution to 1/T1. To this end, we use the standard Korringa relation between the spin-lattice relaxation and Knight shift in metals41; the low-temperature shift value of ≈60 ppm for the sample with 0.2% Nb (Fig. 3) yields 1/T1 values at least an order of magnitude smaller than what is observed (dashed line in Fig. 2). Given the low carrier density, this is not surprising, but it also implies that spin-lattice relaxation cannot provide meaningful information on the electronic subsystem. We therefore focus on the doping and temperature dependence of the titanium Knight shift to gain insight into the local spin susceptibility.

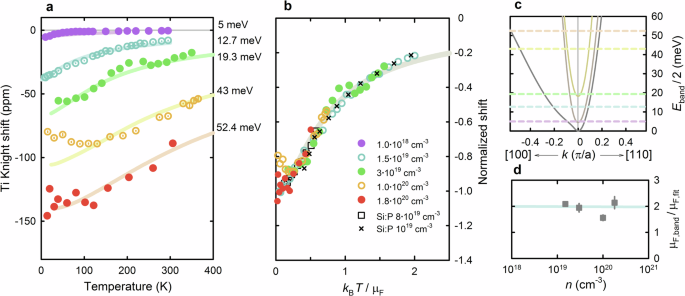

a Temperature dependence of the titanium Knight shift in metallic STO for samples doped via oxygen vacancies (OVD) and Nb substitution. The shifts are strongly temperature- and doping-dependent, in agreement with a nondegenerate Fermi gas calculation (full lines). The best-fit zero-temperature chemical potentials μF are indicated for each theoretical curve. b Scaling of the Knight shift to the theoretical spin susceptibility, for chemical potentials above ~10 meV (the Nb-doped samples). The OVD sample falls outside of the one-band-like scaling regime due to the small chemical potential and is therefore not included in the plot. A comparison to a conventional low-density metal (31P Knight shift in P-doped silicon—squares and crosses, data from refs. 52,53) shows similar behavior. c The low-energy electronic dispersion in tetragonal STO obtained from a tight-binding fit to ab initio calculations65, along two representative reciprocal space directions. The lowest band, which dominates the spin susceptibility at high chemical potentials, is strongly anisotropic (see also Fig. 4 for Fermi surface plots). The best-fit chemical potentials from (a) are marked as dashed lines. d The ratio of the bare-band to best-fit chemical potentials, which is consistent with an approximately twofold, doping- and temperature-independent enhancement of the bare band masses.

Temperature-dependent Knight shift

The measured 47Ti shifts for all studied samples are shown in Fig. 3a. We first note that the shift relative to pristine STO is always negative; this can be readily understood given the fact that the titanium orbitals that make up the metallic state are of d character. There is thus no spatial overlap between the titanium nuclei and conduction electron wavefunctions, and the usual positive contact hyperfine interaction term is zero. Instead, the electrons interact with the nuclei through an indirect core-polarization process, where the spin polarization of the d-like orbitals induces an opposite polarization of inner atomic s-orbitals due to the Pauli exclusion principle48,49,50. This effect is well known in transition metals, and the core-polarization hyperfine coupling constant for atoms with 3d orbitals, such as titanium, is estimated to be Ahf ~ −125 kOe/spin49,50. This value is expected to depend only weakly on the material details since it is mostly determined by the physics of the transition metal core electrons49,50. While the core polarization is only sensitive to the spin part of the electronic susceptibility, screening due to orbital motion of electrons generally leads to an additional contribution to the Knight shift. The orbital shift turns out to be mostly negligible in our case, and we comment on its role in more detail below.

The second important finding is that the Knight shift is strongly temperature-dependent for all studied doping levels, consistent with the spin susceptibility of a Fermi gas with low degeneracy temperatures51. It is known that the Fermi energies in metallic STO are small, and the qualitative trend of the observed behavior is therefore not surprising. However, our measurements enable us to gain quantitative insight: we compare the data to theoretical spin susceptibilities, which we obtain by taking into account the complex band structure of STO27. As established from transport and quantum oscillation measurements, the charge carriers in metallic STO can reside in three distinct bands, which are sequentially filled with increasing doping (Fig. 3c). Even if interactions are neglected, the electronic spin susceptibility thus has a complex internal structure that includes both interband and intraband contributions (see “Methods” for details). When the bare-band zero temperature chemical potential μF,band is higher than ~20 meV, the lowest band dominates the behavior of the susceptibility, and the form of the temperature dependence becomes one-band-like, roughly independent of chemical potential. This susceptibility is plotted in Fig. 3b (solid line), with the temperature/energy scale normalized to the chemical potential (horizontal axis), and the susceptibility normalized to the zero-temperature values (vertical axis), (widetilde{chi }(widetilde{T})=chi (widetilde{T})/chi (0)), where (widetilde{chi }) and (widetilde{T}={k}_{B}T/{mu }_{F}) are the dimensionless susceptibility and temperature, respectively. The dimensionless susceptibility is particularly suitable for comparison with the measured Knight shifts since the hyperfine coupling is eliminated. The measured Knight shifts for samples with sufficiently high chemical potentials, i.e., carrier concentrations above ~1019 cm−3, show similar scaling, in excellent agreement with the theoretical curve (see “Methods” for details of the scaling procedure). The scaling is only possible if the electronic effective mass is temperature-independent throughout the studied temperature range, as assumed in the calculation. This is also confirmed through a direct comparison with data for a conventional low-density metal, P-doped silicon52,53—the 31P Knight shift agrees very well with the STO data and calculated curve. Moreover, we can compare the chemical potentials that yield the best scaling, μF,fit, to values calculated from the bare band structure without any interactions, μF,band. As shown in Fig. 3d, the ratio μF,band/μF,fit is approximately independent of carrier concentration and close to 2. This is consistent with the enhancement of the effective mass with respect to the bare-band mass that was obtained previously from analyses of Drude spectral weight in optical spectroscopy12, low-temperature specific heat measurements43 and quantum oscillation studies7,10, and identified as being due to a coupling between electrons and longitudinal (LO) phonons9,12,54. We use the best-fit chemical potentials and zero-temperature shifts from the scaling analysis to calculate the temperature-dependent Knight shifts (see “Methods” for details), with a comparison to the individual curves shown in Fig. 3a. We note that the sample with 1% Nb concentration (1020 cm−3) shows evidence for a shallow minimum around 100 K; its origin is unknown, and we cannot exclude the possibility of systematic error, e.g., due to slight shifts of the sample in the magnetic field. If the effect is intrinsic, it could be related to a temperature-dependent effective mass m*, but we emphasize that this would imply a decrease of m* with increasing temperature.

Spin-orbit coupling and Wilson ratio

The complex structure of the electronic susceptibility also leads to a departure from the usual linear relation between the low-temperature susceptibility and γ, the electronic Sommerfeld coefficient. The latter was previously determined from specific heat measurements43, and we can make a direct comparison to the spin susceptibility through the Wilson ratio55

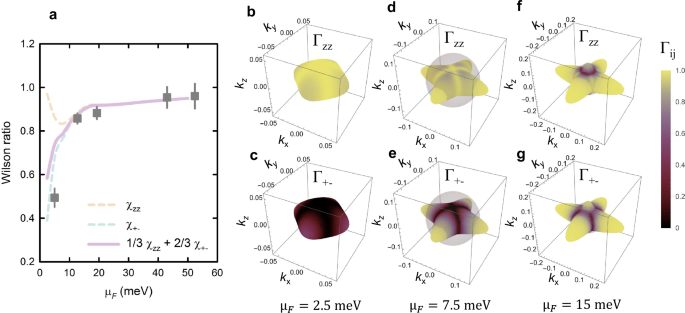

where kB and μB are the Boltzmann constant and Bohr magneton, respectively, and we have assumed an electronic g-factor of 2. The Wilson ratio is equal to one for a free electron gas, where both the susceptibility and Sommerfeld coefficient are proportional to the density of states at the Fermi level. If electron-electron interactions are present, RW can be greater than one, such as in heavy-fermion materials56 and some iron-based superconductors57. Yet, for metallic STO, we observe a significant decrease of the Wilson ratio at low carrier concentrations. This is apparently due to a subtle property of the electronic structure that is captured well by the theoretical calculations (Fig. 4). Indeed, the calculated spin susceptibility shows strong anisotropy in this regime, even though the tetragonal distortion of the crystal structure is very small. Importantly, the measured susceptibility is an average of the out-of-plane and in-plane susceptibilities due to the presence of tetragonal domains, and we thus compare the experimental results to the appropriate weighted average (full line in Fig. 4a).

a The ratio of magnetic susceptibility obtained from the Knight shift and Sommerfeld coefficient γ43 (Wilson ratio) in dependence on the chemical potential at near-zero temperatures (squares). Error bars denote 1 s.d. Conventionally, both quantities are proportional to the electronic density of states, which results in a Wilson ratio of one. In metallic STO, the presence of spin-orbit coupling and tetragonal distortions leads to an effective easy-axis anisotropy at low μF, which significantly lowers the Wilson ratio for the transverse susceptibility. The dashed lines correspond to the calculated longitudinal and transverse susceptibilities χzz and χ+−, respectively, and the full line is an average assuming an equal population of the three types of tetragonal domains. The theoretical μF values have been divided by a factor of 2 to account for the mass enhancement (see Fig. 3). b–g The magnitude of the spin susceptibility matrix element Γij (see “Methods”) plotted on the Fermi surface of the lowest band, for three values of μF. The reciprocal space axes correspond to the cubic structure. A strong suppression of the transverse matrix element is seen at low carrier concentrations (b, c), while the effect becomes progressively weaker as μF increases relative to the tetragonal splitting scale (estimated in (d–g), sphere).

The main reason for both the decrease of the susceptibility and its anisotropy is spin-orbit coupling, which causes the electronic spins to be preferentially aligned with the crystallographic c-axis, i.e., the tetragonal distortion induces an effective easy-axis anisotropy (Fig. 4b, c). Above μF ~ 10 meV, where the lowest electronic band begins to dominate the response, the effects of spin-orbit coupling and anisotropy become much smaller, as demonstrated in Fig. 4d–f, and the Wilson ratio approaches one. Note that the hyperfine coupling was treated as a free parameter in calculating the susceptibilities from the Knight shifts in Fig. 4a, and the value that provides the best match to the theoretical curve is −80 ± 10 kOe/spin, in line with the 3d core polarization value of −125 kOe/spin48, and in excellent agreement with the value obtained from zero-field NMR experiments in ferromagnetic YTiO3, −79.3 kOe/spin58. The decrease of the Wilson ratio should be even more pronounced in doped KTaO3, where the spin-orbit coupling effects are expected to be much larger, leading to significantly reduced electronic magnetic moments due to the entangled orbital and spin degrees of freedom59.

Before we conclude, we briefly comment on the orbital contribution to the Knight shift and its influence on the Wilson ratio. In the majority of metals, the dominant orbital term is quadratic in angular momentum, and its size depends on the total occupation of d-orbitals60,61. It is therefore negligible in the low-density metallic state of STO, where the occupation is less than 1%. An additional linear term appears in the presence of spin-orbit coupling60, which is small in most metals but might play a role at the lowest carrier concentrations in STO. In order to gauge its importance, we calculate the expectation value of the orbital angular momentum of the lowest band (Fig. S5 and “Methods”). Indeed, for μF = 2.5 meV the expectation value is close to 1, while it becomes negligible at higher carrier concentrations. It is not possible to separate the spin and orbital shift contributions experimentally; yet given that the orbital contribution is paramagnetic, it would cause a decrease of the effective hyperfine coupling for the OVD sample. This implies that the Wilson ratio is underestimated, and the subtraction of an orbital contribution might in fact further improve the agreement with the theoretically predicted Wilson ratio for the lowest point in Fig. 4.

Discussion

Our results have several important implications for the physics of metallic STO, and dilute metals more generally. First, we show that the behavior of the electronic subsystem is quantitatively consistent with a nondegenerate Fermi liquid in a wide doping and temperature range. This central result implies that quasiparticles are well-defined, and that temperature only affects their energy distribution in accordance with conventional Fermi-Dirac statistics. The robustness of the susceptibility scaling provides strong evidence for a temperature-independent effective mass, with a moderate mass enhancement that agrees with previous low-temperature studies43. The simple observed behavior provides a microscopic underpinning for theories of both superconductivity and the unusual transport properties of the dilute metal. In particular, our results validate the central assumptions of a model based on two-phonon scattering that explains the persistence of Fermi-liquid-like T2-resistivity at temperatures well beyond the Fermi temperature23. Yet similar behavior of the resistivity has been found in other dilute metals without soft phonons33, and alternative scenarios have been put forward62. The spin susceptibility is a thermodynamic quantity and thus not sensitive to the scattering mechanism, but it does provide an accurate independent estimate of the chemical potential, which we show to be in good agreement with the band structure once the mass enhancement is taken into account. Most importantly, our measurements are not limited to the degenerate Fermi liquid regime and probe the electronic parameters at temperatures comparable to the Fermi energy.

The best-fit chemical potentials (Fig. 3) are also in fairly good agreement with values obtained using other experimental techniques, especially at carrier concentrations below 1020 cm−3. It is known from quantum oscillation studies8,10 that the chemical potentials for samples doped with 0.1% and 0.2% Nb lie below and above the bottom of the third band, respectively, as also obtained from the Knight shift scaling (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, we can compare the best-fit values to a simple estimate of the chemical potential within the free-electron approximation, i.e., assuming that the band structure can be approximated by a single isotropic parabolic band. At high carrier concentrations, the Sommerfeld coefficient then yields an effective mass of ~4me, and the chemical potential for the sample with carrier density 1.8 × 1020 cm−3 can be estimated to be around 30 meV. This is somewhat below our best-fit value of 52.4 meV, and a possible reason for the difference might be the strong anisotropy of the realistic band dispersion. As seen in Figs. 3c and 4, the Fermi surface for the outermost band includes regions where the curvature changes from convex to concave, with an associated divergence of the density of states. This should substantially affect the Fermi energy calculation for a given carrier density. The discrepancy illustrates the importance of taking into account the realistic band structure, even in the regime where one band dominates the response.

The finding of a temperature-independent effective mass invites a reconsideration of the interpretation of recent charge transport experiments, which has suggested a strong increase of the mass with increasing temperature and a crossing of the Mott-Ioffe-Regel limit11. Evidence for a significant mass enhancement has also been found in optical conductivity measurements, as a decrease of the Drude spectral weight with increasing temperature9,13. We stress that NMR provides direct insight into the microscopic spin susceptibility, and the analysis of these data does not rely on any assumptions on the scattering mechanisms and their energy dependence. Moreover, we explicitly take into account the complex band structure of STO; the latter might affect the transport coefficients in a nontrivial way, especially due to interband terms. The decrease of the Drude weight is harder to reconcile with the Knight shift scaling since the optical sum rules are robust, and it is known from charge transport studies that the carrier density does not depend on temperature5. Yet it is not always easy to separate the electronic and phonon contributions in the optical conductivity, especially if the carriers in different bands have substantially different relaxation rates that are comparable to the phonon energies. Nevertheless, the cause of the stark discrepancy between the NMR and optics results remains an open question that might be resolved by a more detailed analysis of the optical data. Furthermore, it would certainly be interesting to expand the NMR experiments into the high-temperature regime, where the electronic mean-free-path becomes very short, while the mobility does not show signs of saturation. More generally, our results show that NMR can be a valuable probe of the electronic subsystem in dilute metals, which can be used to study even the small electronic susceptibilities in such materials in wide temperature and carrier concentration ranges.

Methods

Samples and NMR technique

We have performed 47,49Ti NMR measurements on commercial (MTI Corp.) oriented single crystals of STO, doped with both oxygen vacancies (OVD) and niobium substitution. The vacancy doping was induced by annealing a pristine STO crystal in high vacuum (10−5 mbar) at 900 °C for 2 h, similar to previous work10. Charge carrier concentrations were obtained from Hall number measurements or estimated from the niobium concentration, which is accurate to ~10%. The NMR spectra were recorded with a conventional spin echo pulse sequence, using Tecmag spectrometers and a high-homogeneity (10 ppm) 12 T superconducting magnet (Oxford). High magnetic field homogeneity and accurate placement of samples in the magnet are essential to obtain reliable shift values. The field was always oriented along the crystallographic 〈100〉 direction (cubic phase). Below the cubic-to-tetragonal transition, the samples consist of three types of domains with the 〈001〉 direction along each of the three perpendicular axes. All resonance frequencies are obtained from the raw spectra (Figs. S1–S3) using simple Gaussian fits, and temperature-dependent shifts are calculated as the difference between the frequencies for each doped sample and the interpolated frequencies for an undoped STO crystal. Special care was taken to ensure that the same radio-frequency coil at the same position in the magnet is used for all measurements, including the undoped reference. We focus on the 47Ti isotope due to its slightly larger abundance and faster relaxation. Because of small signal levels and slow relaxation rates, spin-lattice relaxation was measured with a single-shot pulse sequence, where the nuclear magnetization is repeatedly probed during a single relaxation process63.

Spin-lattice relaxation

Phonon-related spin-lattice relaxation processes result from a coupling between the atomic nuclei and electric field gradients created by lattice vibrations. The strength of this coupling depends on both the spin and quadrupolar moment of the nucleus41:

where Q and I are the nuclear quadrupole moment and spin, respectively. For 47,49Ti, the recommended quadrupole moments are 0.247 and 0.302 barn64, and the spins are 5/2 and 7/2, respectively, which leads to an expected ratio of 3.5 for purely quadrupolar relaxation. The temperature dependence is obtained from the phonon density of states, and within the simple Debye model the two-phonon Raman process is given by41

where m is the atomic mass, v the speed of sound, Ω the phonon cutoff frequency (Debye frequency), T the temperature and k Boltzmann’s constant. This function is plotted as a dash-dotted line in Fig. 2, assuming a Debye temperature of 550 K43 and matched to the data at high temperatures.

Scaling procedure

The scaling plot in Fig. 3b is obtained as follows. For each dataset, the temperature and shift axes are rescaled using a simple least-square algorithm to minimize the overall deviation from the theoretical curve. The temperature rescaling parameters are then the best-fit chemical potentials, and the shift rescaling parameters provide the proportionality constants for the theoretical curves in Fig. 3a.

Theory

The static noninteracting spin susceptibility is given by

where g = 2 and μB are the electron g-factor and Bohr magneton, respectively, m and ({m}^{{prime} }) are the band indices, fm(k) the Fermi-Dirac function, εm(k) the electronic dispersion, γ a small broadening, and the matrix element is

where ({hat{S}}_{i}) are spin-1/2 operators, and i, j = x, y, z. The matrix elements for the lowest band (m={m}^{{prime} }=1) are shown in Fig. 4b–g. We compute the q → 0 limit of the transverse susceptibility χ±(q → 0) with spins in the xy plane and longitudinal susceptibility χzz(q → 0) with spins along the tetragonal z-axis. To evaluate Eq. (5) we use a tight-binding parametrization of the relativistic STO band structure obtained from first-principles calculations27,65. The sphere in panels 4d–g shows the tetragonal energy scale of this model, which is given by the split of the dyz/dzx and dxy orbitals obtained from ab initio due to the tetragonal crystal field. We note that there are subtle differences between earlier band structure parametrizations, e.g., ref. 9, and later experiments and ab initio calculations, that are relevant to our anisotropic susceptibility calculation. Namely, the tetragonal splitting parameter was thought to be positive in the earlier work but was subsequently shown to be negative in both quantum oscillation measurements7,8 and recent ab initio calculations. The sign of the tetragonal parameter significantly affects the FS distortion and matrix elements Γzz and Γ+−, and the results shown in Fig. 4 use the more recent, negative value. Yet the averaging due to multiple domain types decreases these effects, and it is likely not possible to reliably discern the difference in experiment. The susceptibility is calculated on a grid of energy/temperature and chemical potential values, and we use polynomial interpolation to fit to the data. The Sommerfeld coefficient in Fig. 4 is computed in a similar way but with the matrix elements set to 1.

To estimate the orbital contribution we compute for the tight-binding model the expectation values (langle {bf{k}},m| {hat{L}}_{i}| {bf{k}},mrangle), where ({hat{L}}_{i}) are orbital angular momentum operators for d orbitals. The results for (langle {hat{L}}_{z}rangle) of the lowest band m = 1, shown in Fig. S5 for the μF values of Fig. 4b–g, indicate that except at very low μF, the orbital contribution becomes very small above μF > 10 meV.

Responses