Early resistance rehabilitation improves functional regeneration following segmental bone defect injury

Introduction

Non-union fractures present a significant clinical challenge, requiring surgical intervention and often result in post-operative complications. While most bone fractures heal spontaneously without surgical or therapeutic intervention, up to 5–10% of fractures fail to heal and result in non-union1. These fractures are often treated with surgical reconstruction and stabilization with fixation hardware in combination with bone grafts or other regenerative treatments as needed2. The complex nature of severe bone injuries often results in post-operative complications, which can lead to costly subsequent surgical and therapeutic intervention3. In addition to surgical repair, patients are often prescribed rehabilitation to promote functional recovery. However, rehabilitation regimens are often conservative and begin with extended periods of non-loading for up to 12 weeks, before progressing through partial weight bearing, range of motion and muscle strengthening exercises, and full weight bearing4,5. Success of these rehabilitation regimens also relies on patients’ discipline, communication, and judgment of pain and swelling6. After this extended process consisting of multiple surgeries and years of painful recovery, patients are often left with long-term disability due to extensive atrophy and fibrosis of the surrounding muscle and soft tissue, even in cases that are considered successful surgical management and bone repair7,8,9,2,10. These factors underscore the need for improved rehabilitation strategies that strive for consistent functional recovery of bone and surrounding tissue.

The emerging field of regenerative rehabilitation focuses on early integration of rehabilitation to enhance the body’s capacity to restore function to the injured limb. It is well established that musculoskeletal cells and tissues (including bone) respond and adapt to mechanical stimuli, and that the relationship between fixation, tissue-level strains, and interfragmentary movement plays a pivotal role dictating the fracture healing process11,12,13. Fixation strategies that load the fracture site result in increased cartilage and chondrocytes in the bone regenerative niche, supporting the hypothesis that increased interfragmentary movement promotes endochondral ossification, whereas stable fixation promotes intramembranous ossification by shielding the fracture from strains14,15,16. However, fixation strategies resulting in excessive strain are detrimental to healing and result in non-union17,18. In the clinic, physical stimuli can modulate biochemical signaling pathways to stimulate the regenerative response of the target tissues19. Using this concept, researchers are leveraging mechanical stimuli for functional healing of weight-bearing musculoskeletal tissue.

Rehabilitation strategies for bone healing require a careful balance between the stability of the bone fixation system and the initiation of mechanical stimulation. Pre-clinical research has begun interrogating this balance through the modulation of fixation plate designs and subject activity. However, lack of standardization between studies and models have led to conflicting results. Several studies have documented that low fixation stiffness is detrimental to healing, as it allows for excessive strain and interfragmentary motion14,20,21. Meanwhile, other studies have observed that increased fixation stiffness suppressed callus formation and subsequent bone healing compared to compliant fixation systems15,22,23,24,25. Researchers have also investigated how the onset of increased mechanical stimuli affects bone healing. Studies have demonstrated that reducing plate stiffness (i.e., dynamization) at 1 week post injury did not improve bone healing and impeded vascularization into the defect region16,26. Conversely, another study showed that dynamization at 1 or 2 weeks post injury led to improved regenerated bone volume and mechanical properties overall, but the course of healing occurred at a slower rate27. Similar trends were seen when dynamization began at 3-4 weeks post injury16,21,28,29. More recently, it was found that increasing plate stiffness after the initial callus formation (i.e., reverse dynamization) accelerated bone healing and mechanical strength14,24,30,31. Specifically, these studies found that increased mechanical stimulation promoted soft callus formation during the early phases of healing, while rigid fixation promoted mineralization in the later stages of bone healing30. This lack of consensus regarding the timing and magnitude of mechanical stimulation is largely due to the lack of standardization between studies regarding the methods and magnitude of mechanical stimulation, fixator stiffness, bone defect size, and animal model32,33,34. Regardless, the principles of mechanobiology suggest that healing responses depend on tissue-level strains. Thus, discrepancies in the literature may be resolved by investigating how individual rehabilitation strategies alter the transfer of ambulatory strains from fixation plates to the regenerative niche. Furthermore, this approach could identify optimal rehabilitation parameters to enhance healing and functional recovery.

Recently, implantable mechanical load sensors were developed to measure the mechanical stimuli experienced in implants and regenerating tissue. Windolf et al. developed an implantable load sensor that continuously monitored implant loading over several months of fracture healing35. The implantable sensor enabled the evaluation of bone healing in a sheep mid-shaft tibial osteotomy model and could eventually be utilized to evaluate patient healing and develop patient-specific treatment strategies36. Barcik et al. also employed a force sensor in sheep to measure the stiffness of the regenerated tissue. The fixator enabled this study to implement loading protocols that were modified based on healing progression37. These technologies have the potential to provide real time, continuous insight into the relationship between loading parameters and bone healing. However, target load parameters and load histories to stimulate bone formation have not yet been established.

Previously, our labs developed implantable, wireless strain sensors and coupled them with finite element models to longitudinally calculate the tissue-level strains following injury and rehabilitation25. In a study, comparing stiff versus compliant fixation plates, we found that the compliant fixation group demonstrated improved mineralized bridging, 60% greater bone formation, and a two-fold increase in strain magnitude compared to the stiff fixation group25. However, torsional stiffness of regenerated femurs from either group did not reach that of intact, contralateral limbs, indicating the potential for further modulation to the local mechanical environment to improve functional healing25. Furthermore, defects were supplemented with bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), which is rarely used for extremity trauma management in the clinic, limiting the generalizability of these results38. Beyond modulating fixation plate materials and design, the mechanical loads and tissue strains can be altered through rehabilitation intensity. Other musculoskeletal injury models have found beneficial effects of increasing exercise intensity, however full characterization of rehabilitation parameters is still lacking in the field12.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the effects of strain within the regenerative niche on segmental bone healing in a rat model. To do so, we surgically created subcritical (2 mm) defects, allowed animals to recovery in sedentary conditions for 1 week, and then animals were either kept in sedentary conditions for the remainder of the study or randomly allocated to rehabilitation with a running wheel with (resistance rehab) or without (no resistance rehab) resistance that was applied by a programmable brake. The impact of rehabilitation on the local mechanical environment and subsequent bone healing was longitudinally monitored through a series of studies by using custom implantable strain sensors, radiographs, and microCT scans. Mechanical testing and histology of explant femurs were performed to investigate how the rehabilitation intensity impacted bone healing. Finally, subject-specific finite element simulations were performed to measure the strains within the regenerative niche based on longitudinal strain data from fixation plate sensors. We hypothesized that mechanical loads induced by resistance rehabilitation would result in increased local strains within the regenerative niche that would then accelerate bone formation and improve functional recovery. This approach may ultimately advance the field of regenerative rehabilitation by enabling data-informed rehabilitation decisions to improve functional recovery following complex bone injuries.

Results and discussion

Resistance rehabilitation starting week one post-injury improved bone healing

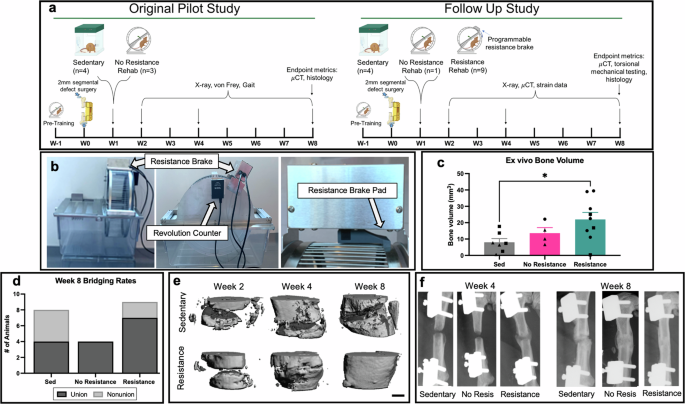

The effect of rehabilitation intensity on bone healing was assessed using a femoral segmental 2 mm bone defect model, which is on the cusp of a critically-sized bone defect. Bone regeneration was assessed longitudinally by radiographs and microCT. After 8 weeks of recovery, 50% of sedentary animal femurs (n = 8) experienced bridging compared to 90% of rehabilitated animal femurs (no resistance rehabilitation, n = 4, resistance rehabilitation, n = 9), suggesting that a 2 mm segmental bone defect in female Sprague Dawley rats is not consistently critically-sized (Fig. 1d). Resistance rehabilitation was associated with significantly greater bone volume within the defect region of microCT scans when compared to sedentary counterparts (Fig. 1c). In addition, early (4 week) callus formation and mature callus consolidation (week 8) were only observed in radiographs of resistance rehabilitation animals (Fig. 1f). Although the majority of femurs from sedentary and no resistance animals were bridged by week 8, representative radiographs and microCT reconstructions revealed distinguishably less dense tissue compared to intact bone throughout the defect region, suggesting less mature healing (Fig. 1e, f). Taken together, resistance rehabilitation starting one-week post-injury was shown to improve bone formation which may be explained by higher intensity exercise leading to early callus formation and more mature healing within our 8-week timeframe.

a Schematic overview of pilot and follow up studies. b Rehabilitation implemented commercial running wheels (Scurry Rat Running Wheel, Lafayette Instruments®) equipped with counters and programmable breaks that can apply resistance and track individual subject’s running activity (number of rotations or distance). Resistance brake pads were modified in-house to apply more consistent friction along the lateral edge of the running wheel. c Bone volume within centered 1.5 mm of 2 mm defects after 8 weeks of recovery. *p = 0.0306, ordinary one-way Anova with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Mean ± standard error of the mean. d Contingency graph of week 8 bridging rates. p = 0.17, Chi-Square test. e, f In vivo representative radiographs and microCT reconstructions reveal early callus formation and consolidation for resistance rehabilitation group only. Scale bar is 1 mm. Triangles = pilot study, squares = follow up study, and circles = animals with sensors implantation from the follow up study. No statistical difference is seen across studies for bone volume results.

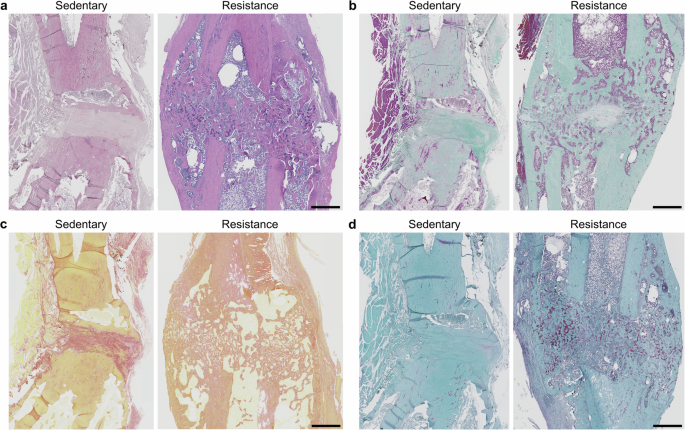

Histological analysis for representative sedentary and resistance rehabilitation animals at week 8 suggests different mechanisms of bone formation across groups (n = 1) (Fig. 2). In sedentary animals, appositional bone formation extends from both ends of the bone with fibrous tissue in the center, while the resistance animals displayed a robust callus bridging the defect site (Fig. 2a, b). Fibrous tissue was visible in the center of the defect in the sedentary rats, while both cartilage and woven bone were visible in the callus of the resistance group (Fig. 2c, d). This suggested that this bone regenerated through endochondral ossification (Fig. 2c, d). This is corroborated by data from the literature demonstrating that lower strains correspond to appositional bone formation, while greater strains promote endochondral ossification39,40,41.

a H&E (b) Goldner’s Trichrome (c) Picrosirius Red (d) Safranin O. Scale bar is 1 mm for all images.

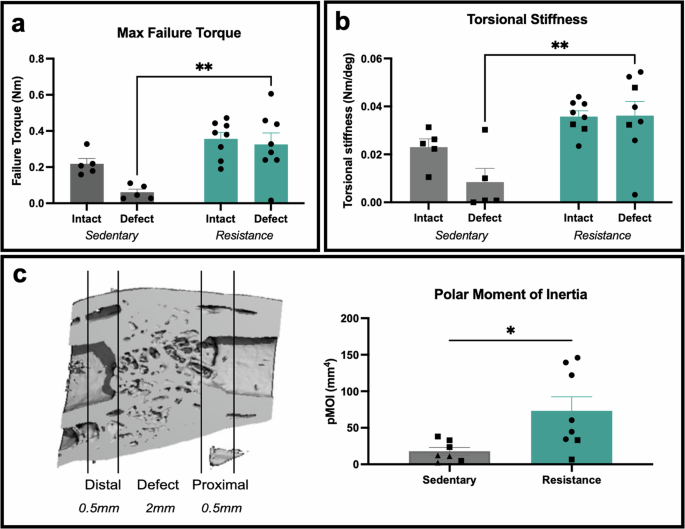

To investigate the impact of resistance rehabilitation on the mechanical properties of the regenerated tissue compared to sedentary counterparts, we performed torsion testing to failure of the defect and intact femurs. Torsional mechanical testing revealed that resistance rehabilitation (n = 9) increased failure torque and torsional stiffness of defect limbs compared to those from sedentary animals (n = 5) (Fig. 3a, b). Furthermore, resistance rehabilitation led to tissue healing with mechanical properties that matched intact femurs (Fig. 3a, b). Data were fitted to a linear mixed effects model with Tukey’s multiple comparisons which revealed a significant effect of rehabilitation condition on the endpoint failure torque (p-value = 0.0041) and torsional stiffness (p-value = 0.0050). Polar moment of inertia of the defect region and bone ends was also significantly increased for rats that underwent resistance rehabilitation compared to sedentary counterparts (Fig. 3c). These results were consistent with the greater callus formation observed in our histology and radiography. Taken together, resistance rehabilitation led to improved healing and mechanical strength of femurs compared to sedentary animals.

a Failure torque of ex vivo femurs under 3°/sec ramp, **p = 0.0023 for sedentary defect versus resistance defect, mixed-effects analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Mean ± standard error. b Torsional stiffness was assessed as the slope of the linear region of the torque-rotation curve. **p = 0.0013 for sedentary defect versus resistance defect, mixed-effects analysis with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Mean ± standard error. c, d Ex vivo polar moment of inertia calculated over 3 mm mid-diaphysis region depicted in microCT reconstructions cross-section. *p = 0.0213, two-tailed unpaired t-test. Mean ± standard error of the mean. Squares = follow up study, and circles = animals with sensors implantation from the follow up study. No statistical difference is seen between surgical conditions.

Rehabilitation may improve pain and limb function

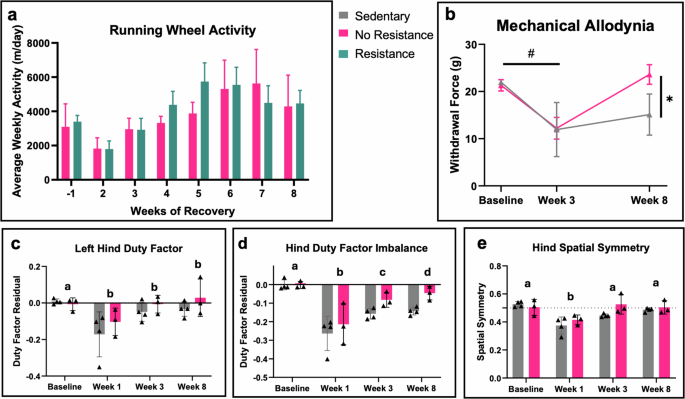

These studies assessed the effect of rehabilitation intensity on bone healing by providing animals with unrestricted access to a running wheel, with or without resistance applied. Running wheel activity level (m/day) could have been a confounding variable for healing outcomes since animals were given voluntary access to running wheels. However, we found no significant difference (p-value = 0.2131) in average weekly running wheel activity between the no resistance and resistance rehabilitation groups, indicating that the differences observed in healing were likely not due to the amount of running activity (Fig. 4a). Both groups decreased running activity from pretraining (3297 m/day ± 471.1, week -1) to week 2 (1802 m/day ± 367.2) following surgery (Fig. 4a). Running activity then increased to post operative levels by week 3 and continued to increase until week 5, at which point running activity plateaued between 4500-5500 m/day (Fig. 4a).

a Weekly running wheel activity averaged across animals throughout all weeks of activity revealed no significant difference between rehabilitation groups, multiple unpaired t-tests. b Longitudinal von Frey demonstrates the impact of injury and subsequent healing on hindlimb mechanical allodynia. Baseline denotes values for rodents prior to undergoing surgery. Significant effects of time p = 0.0006 and combinatorial time and rehabilitation condition p = 0.0350, mixed effects. # denotes significant effects between timepoints; both groups had increased pain sensitivity at week 3 compared to baseline, p = 0.0018; * denotes significant effects between groups at week 8; the no resistance rehabilitation regimen reduced pain levels at week 8 compared to sedentary, p = 0.0224, mixed effects with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. c–e Longitudinal gait analysis depicts hindlimb functionality over time. Data displayed as weight- and velocity- independent residuals of naïve Sprague-Dawley females (c, d). Week 0 denotes baseline values for rodents undergoing surgery. Significant effects over time were observed for (c) left hind duty factor p = 0.0140, d hind temporal imbalance p = 0.0020, and (e) hind spatial symmetry, p = 0.0018. Shared letters indicate no overall difference between timepoints; different letters denote significant overall differences between timepoints, p < 0.05, mixed effects with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. No significant effects were observed between groups at week 8. Triangles = pilot study. Error bars represent standard error of the mean for all graphs.

In addition to bone healing, rehabilitation has the potential to improve gait and mechanical allodynia. A subset of the sedentary (n = 4) and no resistance rehabilitation (n = 3) groups from the initial pilot study were evaluated for pain sensitivity using von Frey filaments to measure mechanical allodynia and for spontaneous gait using an Experimental Dynamic Gait Arena for Rodents (EDGAR). In the von Frey filament analysis, a mixed effects model showed a significant decrease in the overall withdrawal response at week 3 compared to baseline, indicating allodynic pain (p-value = 0.0018); no difference between the treatment groups was observed at week 3 (Fig. 4b, Supplemental Table 1). At week 8, the no resistance rehabilitation animals had a significant increase in the withdrawal response compared to the sedentary animals (p-value = 0.0224), indicating pain relief.

Gait analysis showed an initial hindlimb functional deficit in response to the segmental bone defect injury (Fig. 4c-e, Supplemental Table 2). Using a mixed effects model, there was a significant decrease in the overall left hind duty factor (time the limb spent on the ground) 1 week after injury, though no difference was observed between treatment groups (Fig. 4c). Similarly, there was a significant decrease in the overall hind duty factor imbalance at week 1 post-injury, followed by significant increases at both the 3- and 8-week timepoints compared to week 1 (Fig. 4d). Animals displayed asymmetric placement of the hind limbs 1-week post-injury that improved by week 3, returning to baseline levels (Fig. 4e), indicating that injured limbs had shorter step length (relative to stride length) compared to the uninjured limb. No significant differences were observed between the sedentary and rehabilitation treatments for any gait parameters. While there was an observed effect of the overall injury on initial gait parameters and no observed effect of the rehabilitation treatment, these data are limited by the small sample sizes. Also limiting these data was the lack of the resistance rehabilitation treatment group for these outcomes, as the follow up studies were unable to perform gait and von Frey analyses.

FEA revealed resistance rehabilitation increased compressive and shear strain within the regenerative niche

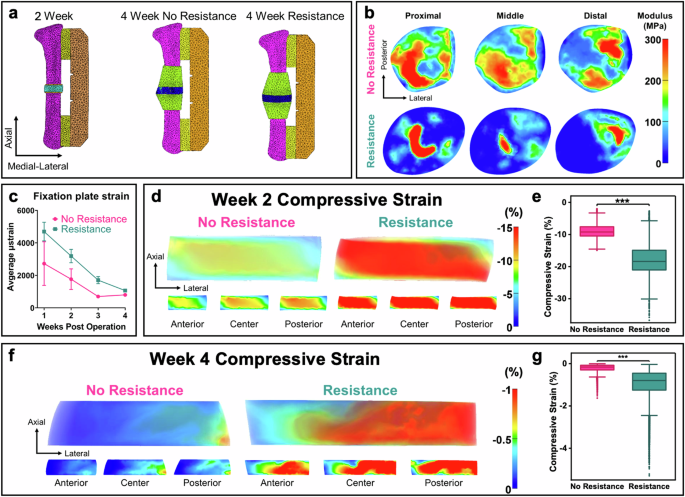

Physical rehabilitation is a promising approach to mechanically stimulate the regenerative niche and encourage the body’s endogenous capacity to heal. Variability in rehabilitation regimens as well as the dependence of tissue differentiation on load onset and magnitude makes it difficult to establish a consensus from the existing literature. Therefore, we assessed the temporal progression of mechanical cues by measuring internal bone plate strain during running wheel activity starting one week after surgery in a subset of the no resistance and resistance rehabilitation groups (n = 1–3). Furthermore, in vivo ambulatory strain measurements were monitored in a subject-specific, real-time manner by our previously developed and validated strain sensor integrated that we integrated into the internal fixation plates42. Dynamic strain cycle amplitudes corresponding to individual steps were computed from strain sensor measurements and the 90th percentile strain magnitudes were recorded for 7 weeks of post injury rehabilitative running (Fig. 5c). Ambulatory strains across the fixation plate gradually declined until bridging was observed in radiographs and microCT scans (Fig. 5c), which is consistent with previous literature25. FE models were then developed using ambulatory strains and microCT images to predict the defect level strains for each physical rehabilitation regimen at weeks 2 or 4 post-injury (Fig. 5a). On average, resistance rehabilitation was associated with a 2.2-fold increase in plate compression throughout week 2 post-injury (Table 1). FE simulations for one representative animal in each group indicated a significant, 2.0-fold increase in 3rd principal strain within the defect region due to resistance (n = 1) (p < 0.001; Fig. 5d, e). For these simulations, compressive strain was greatest in the region spanning the proximal-medial and distal-lateral ends of the defect. Similar trends were observed for shear strain (p < 0.001: Supplemental Fig. 1). Throughout week 4 post-injury, resistance was associated with a 3.3-fold increase in plate compressive strain and a significant, 4.45-fold in defect compressive strain due to resistance (p < 0.001; Fig. 5f, g). Here, compressive strain was greatest on the lateral ends of the bones near the interfaces between intact femurs and defect tissues. Again, similar trends were observed for shear strain in response to resistance rehabilitation (p-value < 0.001; Supplemental Fig. 1). To approximate the changes in strain transfer between the fixation plates and the healing defects, we measured the ratio of the average compressive strain in the defect to measured compressive strain on the plate surface. There was a drastic reduction in this metric between weeks 2 and 4 for both animals (over 8-fold for the no-resistance subject, over sixfold for the resistance running subject) due to bone formation in defects. Notably, defect/plate strain ratio was greater in the no resistance running animal at week 2, but the defect/plate strain ratio was greater in the resistance running animal at week 4.

a Finite element meshes used to evaluate transfer of loads during ambulation between the fixation plates and defects for individual animals. b Transverse plane slices show the spatial distribution of the Young’s modulus for the week 4 models. The no resistance defect displayed intermediate tissue differentiation throughout while the resistance defect only displayed tissue maturation near the intact femur. c Longitudinal graph of the fixation plate strain as a function of rehabilitation time. The strain decreased as healing progressed, but resistance was associated with higher strains across all weeks. Mean ± standard error. d, e 2 week post injury results. d Finite element predictions of 3rd principal (compressive) strain for defect regions are presented in the transverse plane with transparent renderings and slice plots. Strains at 2 week post injury formed a diagonal band between the proximal-medial and distal-lateral regions of the defect. Resistance led to an increase by a factor of 2.0 in the average compressive strain. e Resistance rehabilitation resulted in significantly higher predictions of mean compressive strain within the defect at week 2. ***: p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney U test. Error bars represent 1.5 × inter-quartile range (IQR). f, g 4 week post injury results. f Finite element predictions of 3rd principal strain at 4 weeks post injury. Strain is concentrated on the lateral and central regions of the defects. Resistance led to a greater than 4-fold increase in the average strain. g Resistance rehabilitation resulted in significantly higher predictions of mean compressive strain within the defect at week 4. ***p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U test. Error bars represent 1.5 × IQR.

The benefits of mechanical stimulation for musculoskeletal repair have been investigated using strategies such as axial loading via flexible fracture fixation25,28,43 and controlled mechanical loaders44, low-frequency vibration treatment45, and ultrasonic stimulation46,47. However, there remains a clinical need for data-informed rehabilitation regimens, and a better understanding of how principles of mechanobiology are translated into clinical decisions that improve functional outcomes. To address this need, we investigated the impact of running intensity during rehabilitation on healing outcomes and tissue biomechanics throughout the course of bone healing. Femurs with segmental defects were stabilized with compliant fixation plates integrated with sensors that measured local axial strain during low (no resistance) versus high (resistance) intensity running. Bone healing was monitored via longitudinal radiographs, microCT scans, as well as endpoint mechanical testing and histology. This study provides critical insight into the effects of rehabilitation intensity on bone healing after a segmental bone defect.

This study sought to assess bone healing after implementing a more rigorous rehabilitation protocol compared with our previous work that found improved bone formation with treadmill walking in combination with a low dose of local BMP-2 growth factor therapy25. In the present study, we utilized a smaller defect so the bone healing results was independent of exogenous growth factor dosing. Animals were provided voluntary access to running wheels, facilitating daily running activity (m/day) that were at least 10x greater than treadmill running regimens25. Furthermore, we utilized resistance brakes to modulate rehabilitation intensity. Resistance rehabilitation that started one-week post-injury not only induced significant improvement in bone formation and recovery of mechanical properties compared to sedentary counterparts, but preliminary results suggested early rehabilitation improved tactile pain response. It is widely known that mechanical stimuli are sensed by tissues and cells, which respond by releasing signaling molecules; however the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood48,49. One of the many responses impacted by mechanical stimuli is the inflammatory response, which is known to decrease in response to long-term exercise, potentially resulting in reduced pain49,50. Resistance rehabilitation with compliant fixation significantly increased the failure torque and torsional stiffness of the defect femurs as compared to femurs from sedentary counterparts. Although not significant, the failure torque (p = 0.1337) and torsional stiffness (p = 0.1719) of intact femurs had an increasing trend for animals that underwent resistance training compared to femurs from sedentary counterparts. These data suggest that early resistance rehabilitation results in bone adaptation in the non-injured limb to withstand greater loads induced by resistance running, which is consistent with previous literature12,51,52,53,54. After segmental defect surgery, early resistance rehabilitation led to increased bone healing and strength and promoted full restoration of mechanical properties, which had not been previously achieved in our compliant fixation model. Unsurprisingly, implantable strain sensors measured an increase in fixation plate strain for resistance running animals compared to no resistance animals. Subject-specific finite element models revealed that resistance running induced a beneficial increase in compressive and shear strains within the regenerative niche as compared to no resistance running throughout weeks two and four post-injury (Fig. 5, Supplemental Fig. 1). Overall, our data support resistance rehabilitation, starting one-week post-injury, as a promising therapeutic to increase bone formation, bone healing strength, and promote full restoration of mechanical properties to intact levels for defects on the margin of critically sized without the use of biologics.

The increased compressive and shear strains associated with resistance rehabilitation had a beneficial effect on healing of near critically-sized bone injuries; however, excessive strain can be deleterious. Boerckel et al. quantified the effect of early and delayed loading on neovascular growth in a rat model of 8 mm bone defect regeneration using compliant fixation plates16. In their study, fixation plates were unlocked to allow transfer of ambulatory loads to the defect either at the time of implantation or after 4 weeks of stiff fixation16. Early mechanical loading significantly reduced bone formation by 75% compared to stiff plate controls, which suggested that early loading of high magnitudes in a large defect is deleterious to healing16. Previous work by Ruehle et al. also found that immediate loading inhibited neovessel sprout tip cell selection and angiogenesis while delayed loading (five days) enhanced vascularization, suggesting the need for a brief, critical period of recovery prior to loading55. In acknowledgement of this necessary period of delay, we initiated resistance rehabilitation one-week post operation, resulting in enhanced bone healing of 2 mm segmental defects. However, the variable bone healing results across the literature highlight the significant need for personalized platforms to assess the impact of ambulatory loads on the local mechanical environment throughout healing.

Several studies have investigated how ambulatory load transfers allowed via compliant fixation plates impact healing of critically-sized bone defects treated with BMP-216,24,25,28,56. Boerckel et al. compared healing of 6 mm defects stabilized with either a stiff fixation plate or a compliant plate and treated with 5 micrograms BMP-2. They found that delaying ambulatory loading until week 4 increased bone formation but did not result in mechanical restoration to intact levels. Similarly, Klosterhoff et al. compared healing of 6 mm defects treated with 2 micrograms BMP-2 and stabilized by either a stiff or compliant fixation plate25. Animals were also granted 20 minutes of treadmill walking per week starting after one week of recovery. Compliant fixation and treadmill walking resulted in increased compressive strain magnitudes, bridging rates, and bone formation, however, similarly did not achieve mechanical restoration25. Glatt et al. also compared healing of 5 mm defects treated with 11 micrograms of BMP-2 and stabilized with external fixation plates at different stiffnesses56. Radiographs and histology revealed that low stiffness fixation produced the best healing after eight weeks56. A follow-up study then assessed healing due to constant fixation stiffness or reverse dynamization (fixation stiffness was increased after 2 weeks). MicroCT, histology, and radiographs revealed that reverse dynamization resulted in greater bone formation and mechanical properties that matched intact levels. All these studies found promising bone healing results with different loading regimens and timing, suggesting that bone healing response is more complex than merely a single strain value threshold. In addition, these studies did not result in complete functional restoration. It is also worth noting that these studies all supplemented rehabilitation with BMP-2, which has been established as a robust bone forming growth factor38,57,58,59,60, and is likely a confounding factor in these healing results. In comparison, we found that resistance running significantly increase bone formation as compared to sedentary counterparts and restored femurs to intact strength without the use of biologics.

Although mechanical loading has been a longstanding therapeutic for musculoskeletal injuries, the magnitude of loading through all stages of fracture healing is not well understood52,61,62, largely because of the technological challenges of acquiring accurate, local measurements. We addressed this hurdle by utilizing implantable strain sensors to track longitudinal, real-time measurements of bone plate strain throughout rehabilitative activities to assess healing and predict bone healing well before radiographic evidence. In fact, the relationship between early strain amplitudes and healing outcomes previously revealed a significant positive relationship between strain amplitude one week after injury and regenerated bone volume after 8 weeks of healing25. For the present study, these same sensors revealed that resistance running increased local strains across the fixation plate and within the regenerative niche, which led to improved bone healing of 2 mm bone defects. A limitation of the sensor platform used for these rodent studies is that it requires a transceiver pack and has a restricted battery life. Further development of battery-free sensors that do not require a transceiver could facilitate clinical translation and potentially enable data-informed revisions to rehabilitation parameters that improve functional healing.

The goal of this study was to explore how rehabilitation intensity can be utilized to produce mechanical loading advantageous to bone healing of defects on the margin of critically-sized. We previously used finite element simulation to predict the difference in defect-level mechanics facilitated by stiff or compliant fixation plates supporting 6 mm defects during two weekly, 10-minute treadmill walking at 3 weeks post injury25. Defects supported by compliant fixation plates experienced a 60% increase in bone formation when compared to defects supported by stiff fixation plates. Compliant plates facilitated defect compression between ~1 and 6% while stiff plates facilitated compression below 1%. In the present study, only a compliant plate was used, and animals were provided unrestricted access to running wheels with or without resistance. Both the prior and present studies began rehabilitation at 1-week post injury. We found that resistance rehabilitation facilitated defect compression in the ~1–6% range at 4 weeks post injury while rehabilitation without resistance facilitated defect compression in the ~0–2% range. Thus, compression in the range of ~1–5% strain at 3-4 weeks in the course of healing was associated with greater bone formation in both the previous and current studies. Notably, increased rehabilitation intensity was necessary to achieve a similar range of compression in this study. This was likely due to differences in defect geometry and severity of trauma. Researchers have also previously proposed that maintaining a 2–10% strain between fracture ends enables relatively stable secondary fracture healing, while excessive or insufficient strain may affect secondary healing and lead to non-union or delayed union52,63,64,65,66,67. However, these observations were made without implantable sensors to track local biomechanics longitudinally, and they relied on various animal models, defect sizes, and fixation strategies. Nevertheless, we found that defect compressive strains for both no resistance and resistance animals were on the higher end of this range after 1 week of rehabilitation. These data demonstrate the importance and potential of patient-specific pre-surgical planning and rehabilitation protocols based on the condition of each injury68,69.

Literature has established that cage enrichment improves the mental and physical fitness of laboratory rodents including rats70. Recent work has also found that psychosocial stress can negatively impact fracture healing, while free-running wheel access is highly rewarding to rodents71,72,73. The healing improvements in the rehabilitation groups could be partially explained by the improved fitness state of these animals, with resistance potentially intensifying the impact of exercise on the whole fitness of the animal. However, sedentary rats received enrichment throughout recovery to support their mental and physical fitness as well. All groups were housed in conditions that minimized stress and provided rewarding enrichment.

In this study, several limitations are worth noting including (1) only female animals were included (2) resistance varied with each revolution during wheel running (3) not all groups were included in each study, and (4) simplification were made for computational models of tissue material behavior. First, female rats were selected to avoid confounding complications due to the rapid skeletal growth and weight gain observed in male rodents. Future work is warranted to investigate the effect of sex on rehabilitation-induced bone regeneration. Second, the resistance brakes exhibited variable resistance throughout each revolution due to brake pad pressure on a spinning wheel that was not perfectly true. The inconsistent resistance level was not fully quantified, but the increased strain on the defect was measured. Third, due to the novel technology that this work involved, we performed a pilot study followed by a larger study to mitigate the chances of unwarranted pain or suffering of rodents. Study conditions did not significantly impact bone volume and mechanical testing data (Supplemental Fig. 2), thus allowing us to combine results to investigate statistical differences between experimental groups. In addition, all rodents were the same strain, sex, and age, and they all underwent similar orthopedic procedures. A final limitation of the study is the choice of linear isotropic elastic solids for computational modeling of tissue material behavior. This simplification neglects the viscoelastic and fluid properties of healing bone. Nonetheless, this assumption is appropriate for the purpose of quantifying the average ambulatory load transfer to the regenerative niche. Bone growth and remodeling occur on a much larger time scale than ambulatory loads (weeks-months versus seconds). Previous computational models of tissue differentiation have found that tissue growth kinetics are primarily affected by the transient (i.e., steady state, time-averaged) stress rather than the dynamic stress74,75. Thus, we chose not to model viscoelasticity or fluid motion for this study.

Overall, our findings support early resistance running as a post injury treatment for near critically-sized segmental bone defects because it facilitated advantageous loading conditions, which resulted in improved bone healing. Previous literature is contradictory on whether early ambulatory loads are advantageous or deleterious to healing, highlighting the need for personalized measurements to inform rehabilitation decisions that accommodates for fracture type, geometry, and severity16,25,28,56. We combined implantable strain sensors and FEA to highlight a promising platform for tracking patient-specific, real-time defect strains throughout rehabilitation and healing. Future efforts will take advantage of this platform to identify rehabilitation revisions in real-time during rehabilitation in hopes of improving and accelerating functional recovery after traumatic bone injury.

Methods

Strain sensor fabrication

A digital transceiver unit was developed as previously described42. This device relies on wireless Bluetooth Low-Energy (BLE) microcontroller (MCU) to receive commands and transmit data via a custom PC software (Visual Studio) and is powered by a 620 mAh lithium coin-cell (CR2450, Panasonic). The transceiver unit was encased in a 3D printed housing unit with two multistranded stainless steel wires (A-M systems) connected to a strain sensor (EA-06-125BZ-350/E, Micro-measurements) integrated into a custom internal fixation plate used to stabilize the femoral defect. The internal fixation plate is radiolucent and fabricated with ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE, Quadrant) to promote load sharing across the defect. Before implantation, each device was calibrated using a three-point bending flexural test on a tensile testing machine (TA Electroforce 3220) to physiologically relevant strain magnitudes42.

Surgical procedure

As previously described15,25,38,42,57,60, unilateral 2 mm segmental defects were created in the left femur of 17-wk old female SASCO rats that weighed between 200-275 grams (Sprague Dawley, Charles River Labs). Rats were anesthetized by isoflurane (Vet One Fluriso) for the entire surgical procedure with rodent toe pinch and respiratory checks every 15 minutes. Rats were subcutaneously given a dose of 1 mg/kg of Slow-Release Buprenorphine based on their preoperative weight at 1 mg/mL concentration immediately prior to surgery. During surgery, femurs were stabilized with load-sharing internal fixation plates prior to creating the defects25. Due to the novel technology involved in this study, we first performed a pilot study followed by a larger, follow up study (Fig. 1a). A subset of animals within each group in the larger, follow up study were provided fixation plates integrated with strain sensors. For these animals, transceiver packs were mounted in the abdominal cavity and the wire connecting these pieces were subcutaneously fed through a keyhole incision in the abdominal wall superior to the left inguinal ligament. Defects were left empty to better discern the impact of exercise without biologic treatment as a confounding factor. Animals were randomly allocated to experimental groups: sedentary control, no resistance rehabilitation, or resistance rehabilitation. Postoperative complications such as tissue necrosis, hardware failure, or signs of persistent mobility deficiency were considered exclusion criteria and resulted in early euthanasia (sedentary n = 2, no resistance n = 2, resistance n = 1). Animals without postoperative complications were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation after 8 weeks of recovery. All procedures were approved by the University of Oregon IACUC (20-32) or Atlanta Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center IACUC (V019-19).

Voluntary wheel running and housing conditions

Prior to surgery, all rats were acclimated to running wheels where they had voluntary access to in-cage running wheels with no resistance applied (Scurry Rat Running Wheel, Lafayette Instruments®). After surgery, rats were singly housed in standard sedentary cages (Tecniplast rodent housing cage) and allowed 7 days to recover. All rats received nesting, enrichment materials including a PVC tube, crinkle paper, Nylabones, and nestlets before and after surgery. Non-sedentary animals were then granted voluntary access to a running wheel with either no resistance or pre-programmed 25%-40% body weight resistance applied via programmable brakes (rat brake, Lafayette Instruments®). Running wheels with resistance created higher intensity rehabilitation due to the friction between the resistance brake pad requiring greater force to move the wheel (Fig. 1b). Animals were weighed on a weekly basis and the resistance levels were changed to ensure resistance levels were maintained throughout the 7 weeks of rehabilitation. Running activity (m/day) was longitudinally monitored using onboard rotation monitoring sensors (Scurry Rat Activity Sensor, Lafayette Instruments®). Animals in the sedentary group were singly housed in standard cages with no wheel for the full 8-week recovery duration.

Wireless strain data acquisition and analysis

Strain measurements were transmitted in real-time via Bluetooth connection to a nearby laptop and plotted on a custom Microsoft Visual Studio C# graphical user interface (GUI) during 10-minute wheel running sessions performed twice weekly. These measurements started after the 7-day post injury recovery period and continued until the week 8 endpoint. Strain measurements were collected for animals with implanted sensors and given access to a wheel (no resistance and resistance animals). A custom MATLAB (MathWorks, version 9.11.0.1809720) script identified local maxima and minima pairs to track individual step cycles and compute the average 90th percentile of strain amplitudes per animal across each week of post injury rehabilitation.

Gait analysis

Post injury hindlimb function was assessed in the initial pilot study using an Experimental Dynamic Gait Arena for Rodents (EDGAR) that provided quantitative assessment of rodent hindlimb function76. Prior to surgery, rats were acclimated to the gait arena for 20 mins across 3 consecutive days. Gait was assessed at baseline (1 week prior to surgery) and at weeks 1, 3, and 8 post injury with a high-speed camera (500 fps, 1920×1200, Phantom Micro 320, Vision Research, Inc, Wayne, NJ). Videos were processed in the EDGAR software package77 which automatically tracked rats, isolated fore and hind limbs, identified foot-strike and toe-off, and calculated the following gait parameters: velocity, stance times, stride times, imbalance, step widths, stride length, and spatial/temporal symmetries (Supplemental Fig. 3). Spatiotemporal parameters were corrected for each rat’s mass and velocity based on a healthy databased established within our lab. Parameters are then reported as residuals from the expected value of a healthy rat at a given mass and velocity, as established by Kloefkorn et al76.

Von Frey pain testing

Mechanical allodynia of the hindlimbs was measured in the initial pilot study using a 50% withdrawal threshold with von Frey filaments. Animals were acclimated to the protocol with 3 days of consecutive pre-testing. Von Frey filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA) were applied through the bottom of a wire cage and held to the plantar surface of the hind paws for 5 s. A positive response was defined as the animal withdrawing, licking, or shaking its paw. The protocol started with a moderate filament (10 gram-force) and then moved to a smaller filament if there was a response or a larger filament if there was no response. Only one stimulus was applied per minute until 5 total stimuli were applied, or until a threshold of 26 gram-force was reached.

In vivo microCT and radiography

Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (Vet One Fluriso) for in vivo radiography and microCT scans acquired at 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-injury. Digital radiographs were captured at 40 kV with a 7 s exposure time (Faxitron MX-20). MicroCT scans were performed using 48 µm voxel, 55 kVp, 145 µA, and 750 ms integration time (VivaCT 80, Scanco Medical). Radiographs were accessed for bridging by blinded scorers. Representative longitudinal 3D reconstructions were exported using Scanco software to track healing across weeks 2, 4, and 8.

Ex vivo microCT and biomechanical testing

Animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, left and right femurs were dissected and cleaned of soft tissue, fixation plates were carefully removed from the left femurs, and femurs were wrapped in PBS-soaked gauze and placed in 15 mL conical tubes at 8 weeks post injury. Ex vivo microCT scans were performed by centering the conical tubes on the appropriate tube holder (VivaCT 80, Scanco Medical) and using 36 µm voxel, 70 kVp, 114 µA, and 200 ms integration time for the initial pilot study or 24 µm voxel, 55 kVp, 145 µA, and 750 ms integration time for the follow-up studies. A standard 1.5 mm long cylindrical volume of interest (VOI) was used to evaluate trabecular bone formation between intact bone ends of 2 mm segmental defects. Results were reported as bone volume (BV). After scans, all femurs were stored at –20 °C in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) soaked gauze until biomechanical testing was performed 3 days later. As described in Klosterhoff et al., explanted left (defect) and right (intact) femurs were biomechanically tested to determine the failure strength and torsional stiffness25. Ex vivo femurs were tested to failure in torsion at 3°/sec using a load frame (TA Electroforce 3220). Functional analysis involved inter-animal comparisons between defect (left) and intact (right) femurs as well as comparisons between the sedentary and resistance rehabilitation groups.

Finite element analysis

The mechanical environment (compressive and shear strain) in the rehabilitative niche was quantified by finite element simulations of one no resistance- and one resistance-running animal at 2- and 4-weeks post injury. First, an idealized geometric assembly of a left femur and fixation plate assembly was created from our previously published study25. Week two post-injury geometries were created by sectioning the intact idealized femur to create a 2.0 mm defect. The top and bottom of the defect were treated as fibrous ectopic tissue. The middle region of the defect comprising the granulation tissue was modeled by generating a cylinder between the proximal and distal ends of the femur. Week four post-injury geometries were similarly derived from the idealized initial geometry. Subject-specific defect geometries were extracted from microCT images and then the idealized femur was aligned with the visible portions of intact bone in the defect microCT images. Ectopic bone surfaces were approximated from radiographic measurements in the current study. All geometries were meshed with 10-node quadratic tetrahedral elements of a similar size as used in our previous models, which were validated by mesh convergence studies25. Nodes between model components were welded into a single compatible mesh such that contact did not need to be explicitly modeled. Geometries, volume meshes, and material property assignments were performed in Mimics (version 24.0) and 3-Matic (Materialise, version 16.0). Simulations were performed in FEBio (www.febio.org, version 3.7, Salt Lake City, UT) and results were visualized with FEBioStudio (version 2.0)78.

All materials were modeled as isotropic elastic solids. The material coefficients for the sensor plate, riser, and intact femur were assigned from our previously published study25. The same homogenous material properties were assigned regardless of rehabilitation intervention since minimal healing and tissue differentiation were expected at 2-week post injury. Granulation tissue and fibrous tissues were assigned material coefficients compiled from the literature (Supplemental Table 3). Material coefficients for the defects at 4-weeks post injury were derived from microCT image data. The Young’s modulus was assigned to each finite element from the relationship (E={s}_{E}{rho }^{1.49}) where sE is a scalar (MPa) and ρ is the local image intensity (arbitrary units in the range [-1000, 12631]). The Poisson’s ratio was assigned to each finite element from the relationship (nu ={s}_{nu }{rho }^{0.64}+0.166) where sv is a scale factor (no units). These coefficients were selected so that the values agreed with prior literature (Supplemental Table 3). Ectopic growth was not entirely detected by the microCT images; thus, ectopic tissues were assumed to be homogenous with material coefficients derived from the literature79.

Model loading and boundary conditions were prescribed similar to previous simulations25,80,81. Material properties for week 4 defects were assigned based on intensity units in Mimics (Materialise). Volumetric tetrahedral-10 elements were grouped into bins based on the average intensity (arbitrary units, range of -1000 – 12631). Bins with negative values were assumed to be comprised of granulation tissue with properties similar to connective tissue. The remaining material properties were assigned based on the relationship:

Here, E is the young’s modulus (MPa) and ρ is the intensity value (arbitrary units), and sE is a scalar. The scalar sE was determined by assuming that immature bone has a young’s modulus E = 500 MPa and intensities equal or greater to 9000. From this, we set sE = 6.41e-4. The Poisson’s ratio was similarly determined by a power relationship:

Here, sv is a scalar. This equation was fit with sv = 2.25e-5 such that intensities corresponding to granulation tissue, fibrous tissue, and immature bone matched values in the literature. The distal end of the femur was fixed in all directions. A spatially-varying pressure was assigned to facets on the surface of the femoral proximal surface from the Euler-Bernoullibeam-bending relationship seen in Eq. (3):

where y is the anterior position and x is the medial position of the element surface. The total normal stress σ was the sum of the axial compressive stress (σc), the bending stress

about the medial-lateral axis (σml), and the bending stress about the anterior-posterior axis (σap). Here, x was the medial position of the element surface and y was the anterior position of the element surface. The parameter A was iteratively varied until the average compressive (3rd principal Lagrange) strain across the fixation plate matched experimental measurements of compressive strain from the implantable strain sensors for each model (Supplemental Table 4). Pressures were assigned to surfaces of elements on the femoral head. The pressures varied based on anatomical position of a left femur in the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral orientations (Supplemental Fig. 4). Compressive (3rd principal) and shear strain values were then extracted from the elements in the defect to generate descriptive statistics and comparative analyses between models. Elements from mineralized tissues were excluded to restrict the analysis to the granulation tissue.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with Prism 9 (GraphPad) unless otherwise noted. Power calculation was performed with G*Power software using historical and pilot data to determine a sufficient group size of 7. Ordinary One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons was used to compare endpoint bone volume across experimental groups. Mixed effect analyses were used to investigate which variables (time, rehabilitation condition, or the interaction) may contribute to difference in hindlimb functional outcomes differences between sedentary and no resistance animals. Average weekly distance (m/day) across time and between rehabilitation groups were assessed by multiple unpaired t-tests. Mixed effect analyses with Tukey’s multiple comparisons were also utilized to investigate the mechanical properties of explanted femurs from animals in sedentary conditions versus resistance rehabilitation. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM since experimental groups had unequal sample sizes due to postoperative complications and the inclusion of multiple studies. Mann-Whitney U-tests were performed for measurements derived from FE simulations using Origin 2020b (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Statistical significance is shown with asterisks and exact p-values are listed in figure headings.

Responses