The bsh1 gene of Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 ameliorates liver injury in colitis mice

Introduction

The Western diet (WD) is characterized by high fat, sugar, cholesterol, protein, and excess salt and is associated with inflammatory, metabolic, and autoimmune diseases1,2. An unhealthy diet can lead to changes in the community structure and metabolites of commensal bacteria in the gut, which in turn may produce harmful substances that affect liver function, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), deoxycholic acid (DCA) and succinate3,4,5,6,7. Additionally, studies have indicated that the Western diet increases gastrointestinal permeability, which worsens liver function in older monkeys and is likely to contribute to the development of chronic inflammation8. In addition, the diet has a very strong influence on the gut microbiota, with different ratios of fat, protein, and carbohydrates significantly affecting the composition and function of the gut microbiota, and consequently the metabolism of the host9.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with hepatobiliary pathologies such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), hepatic amyloidosis and granulomatous hepatitis10,11. MASLD can trigger hepatic and intestinal inflammation by affecting lipid metabolism and the intestinal barrier, and intestinal inflammation in turn damages the hepatic and intestinal circulation further exacerbating the MASLD phenotype10. The intestinal immune system is an important regulator in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. Studies have shown that interleukin 17 (IL-17) secreted by T helper cell 17 (Th17) cells inhibits the expression of the fatty acid transporter Cd36 in epithelial cells and reduces lipid uptake and absorption and that dietary sugar disrupts the homeostasis of the intestinal flora in mice leading to a decrease in immune cells and an increased risk of lipid metabolism disorders. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) also links inflammation to lipid metabolism. TLR4 exposure to bacteria causes the bacteria to activate the host immune system, making it more sensitive to adipose tissue12. Guo et al.13 found that during inflammation, the SREBP cleavage activating protein (SCAP)-Sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 (SCAP-SREBP2) complex, an important cholesterol receptor, promotes the activation of the NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, thereby linking cholesterol synthesis to inflammatory signaling, which together promote macrophage activation and inflammation. Wei et al.14 found in mouse experiments that tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) increased the expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1C) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) through activation of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), and when TNF-α was inhibited, the expression of SREBP-1C and FAS was also inhibited, and hepatic lipid ab initio synthesis was reduced.

In recent years, probiotics have been widely developed, such as regulating intestinal flora, anti-inflammatory, regulating lipid metabolism, and alleviating obesity15,16,17. Bacteria with bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity are involved in several pathways in the organism, such as those involved in lipid metabolism, intestinal homeostasis, inflammation, and circadian metabolic pathways18. Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and have the effect of emulsifying fat19. Disturbed bile acid metabolism leads to impaired intestinal barrier function, which in turn leads to systemic inflammation20, and reduced secondary bile acid synthesis negatively affects lipid homeostasis19,21,22. Bile acid conversion is influenced by bile salt hydrolase (BSH) expressed by intestinal bacteria. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are considered probiotics with high BSH activity.

Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 screened from Xinjiang pickled cabbage is considered to have probiotic properties, our previous studies have shown that the presence of AR113 (particularly the bsh1 gene) plays a key role in alleviating colitis exacerbated by a Western diet, but the specific effects of AR113 on the liver remain unclear. We aimed to investigate whether AR113 could alleviate liver injury by modulating hepatic lipid and bile acid metabolism. In this study, we demonstrated that AR113 could ameliorate liver injury and hepatic inflammatory response by regulating lipid and bile acid metabolism, altering the structure of intestinal flora, maintaining the health of intestinal microecology, and inhibiting the expression of SREBP-1C and P-NF-κB at the protein level.

Results

AR113 regulation of bile acid and fatty acid metabolism

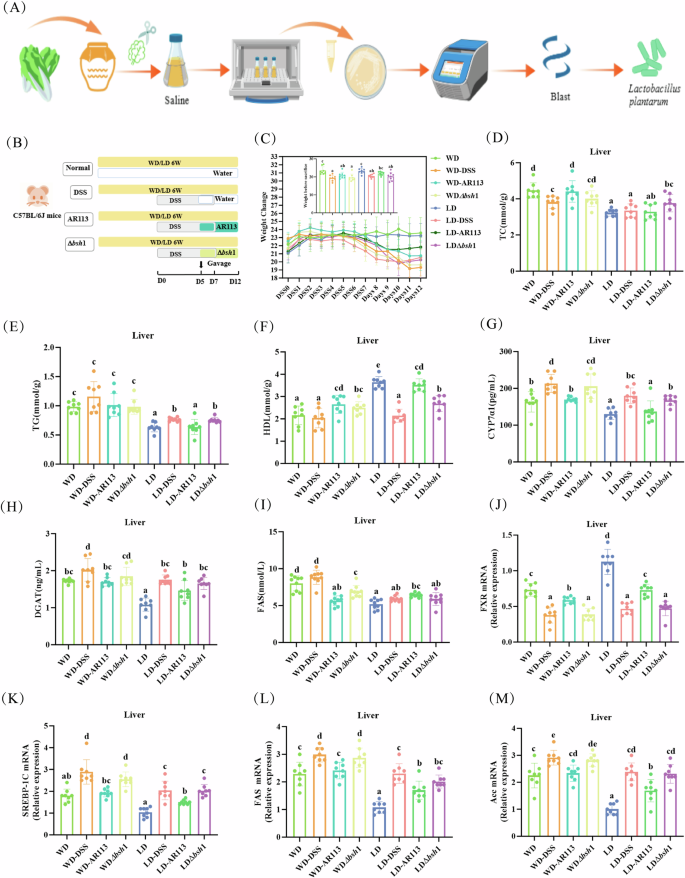

The screening process and animal experimental flow of AR113 are shown in Fig. 1A, B. After modeling with DSS, we monitored the body weight of the mice daily. On the fifth day of DSS administration, mice began to exhibit a dramatic weight loss. However, with the probiotic gavage intervention, AR113 partially mitigated the sharp decline in body weight caused by colitis under the dietary intervention (Fig. 1C). Additionally, AR113 supplementation increased food intake to some extent in colitis mice, but had no effect on water consumption (Fig. S1A, B). We found that TC and TG levels were elevated and HDL levels were reduced in mice in the WD group compared to the LD group. This means that four weeks after the Western diet intervention, the blood lipids were abnormal. However, in the WD-DSS group, TC was decreased and TG was increased to some extent, suggesting that DSS treatment may inhibit hepatic FXR activation and thus affect the metabolism of fatty acids and bile acids. The intervention of AR113 restored TC and HDL levels (Fig. 1D, F, P < 0.05), but the knockout strain lacking the bsh1 gene could not regulate these levels. In the LD group, TG levels were increased and HDL levels were decreased in the LD-DSS group, and AR113 reversed these changes (Fig. 1E, F, P < 0.05).

A Screening and characterization of AR113 (Flowchart created with BioGDP.com50); B Experimental design; C Changes in body weight of mice during the modeling phase of DSS, with bar graphs showing pre-sacrifice body weights of the mice; D−F TC, TG and HDL-C levels in the liver; (G-I) CYP7α1, DGAT, and FAS activities in the liver; J–M Gene expression of FXR, SREBP-1C, FAS and ACC in the liver. Different letters (a, b, c, and d) indicate significance (P < 0.05), n = 8.

To test our hypothesis, we performed ELISA and quantitative PCR to determine whether AR113 regulates genes and enzymes related to bile acid synthesis and fatty acid metabolism. First, we found that the activities of bile acid synthesis and fat metabolism-related enzymes were significantly changed in the livers of WD mice compared with LD mice, with increased CYP7A1, DGAT, and FAS enzyme activities, and decreased HL enzyme activities (Fig. 1G–I and S1C, P < 0.05), and the WD-DSS group had a more significant difference, which suggests that the interventions of WD and DSS inhibit the hepatic ability to regulate bile acids and fatty acids. Additionally, at the transcriptional level, DSS-treated mice exhibited increased expression of SREBP-1C, FAS, and ACC, along with decreased expression of FXR and PPAR-α (Fig. 1J, M, and S1D, P < 0.05). These findings confirm that DSS treatment may suppress hepatic FXR expression and disrupt the synthesis of hepatic fatty acids and lipid metabolism. AR113 treatment rescued the hepatic lipid metabolism abnormalities with decreased levels of CYP7A1, DGAT, FAS, and SREBP-1C and increased levels of fatty acid metabolism-associated protein, PPAR-α (Fig. 1G–I, K and S1D, P < 0.05). Similarly, increased fecal total bile acid excretion in the WD and WD-DSS groups confirmed that the enterohepatic circulation was compromised and that AR113 intake reduced fecal total bile acid levels (Fig. S1E, P < 0.05). However, these changes were not noticeable in the AR113Δbsh1 treatment (Fig. 1G–M and S1C, D, P > 0.05).

AR113 can alleviate liver inflammation phenotype

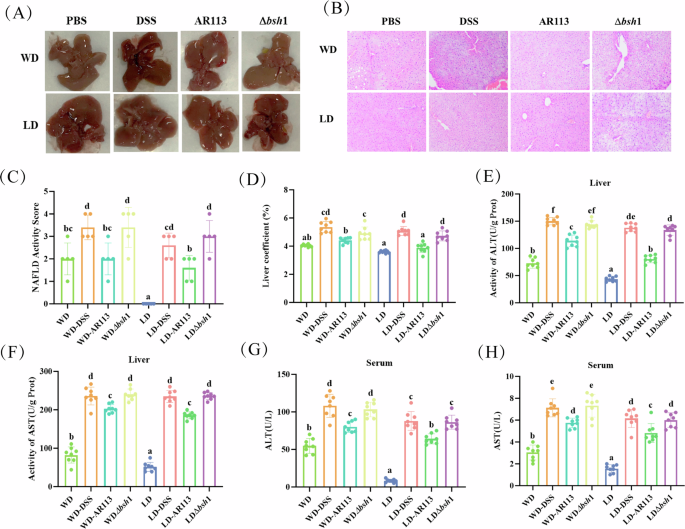

We found that the livers of mice fed a Western diet were yellowish. After DSS intervention, the liver tissue was fragile and friable. After treatment with AR113 by gavage, the color, and texture of the liver improved (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, we performed H&E staining of the livers and showed that the WD diet led to the development of numerous fatty vacuoles between hepatocytes in the mice, whereas the DSS intervention resulted in markedly swollen and misarranged hepatocytes with ballooning and intrahepatic lobular inflammation (Fig. 2B). AR113 rescued the deteriorated hepatic pathologic manifestations of the DSS-treated mice, reduced liver coefficients and NAS scores and significantly suppressed liver and serum elevations of ALT and AST (Fig. 2B–H, P < 0.05). In contrast, AR113Δbsh1 did not show a superior effect in attenuating hepatic pathology or improving liver function markers.

A Liver phenotype; B Liver H&E staining (200×); C NAFLD activity score (n = 5); D Liver coefficient; E, F The liver ALT and AST levels in mice; G, H Serum levels of ALT and AST in mice. Different letters (a, b, c, d, and e) indicate significance (P < 0.05), n = 8.

AR113 attenuated liver inflammatory factor level

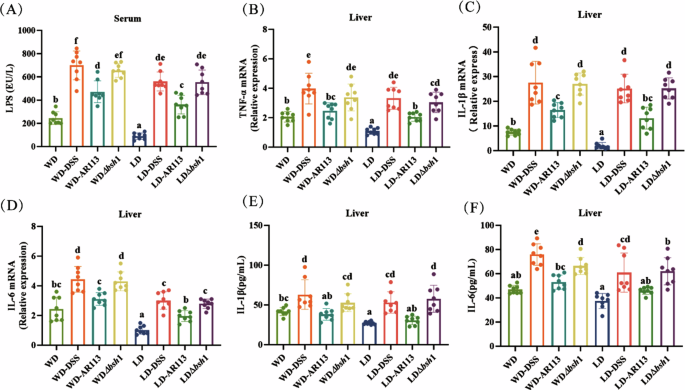

Then, we further determined the effect of AR113 on the hepatic inflammatory response in mice. We found that the levels of LPS, TNF-α, and IL-1β were significantly increased in the WD group compared with the LD group (Fig. 3A–F, P < 0.05). Similarly, after 4 weeks of dietary intervention, the WD-DSS group had higher levels of LPS and inflammation. As expected, AR113 improved the hepatic inflammatory response in mice (Fig. 3A–F, P < 0.05), and AR113Δbsh1 did not have a better mitigating effect (Fig. 3A–F, P > 0.05).

A Serum LPS levels; B−D Gene expression of liver TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6; E, F Protein level of liver IL-1β and IL-6. Different letters (a, b, c, d, and e) indicate significance (P < 0.05), n = 8.

AR113 inhibits SREBP-1C and P-NF-κB p65 expression at the protein level

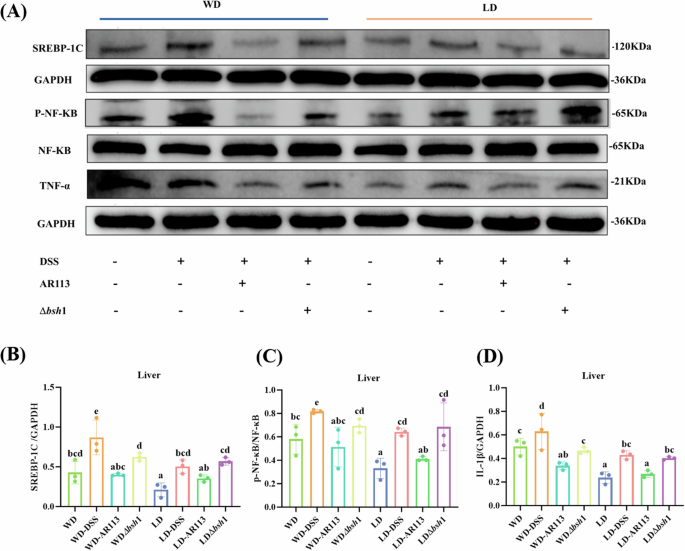

We hypothesized a potential link between inflammation and lipid metabolism. Western blot analysis revealed that both WD and DSS interventions elevated the expression of TNF-α, SREBP-1C, and P-NF-κB p65 in liver tissues to varying extents (Fig. 4A–D, P < 0.05). Notably, the WD-DSS group exhibited higher gray values for these proteins compared to the LD-DSS group, suggesting that dysregulated lipid metabolism may exacerbate the inflammatory response. Moreover, SREBP-1C levels were significantly higher in DSS-treated mice compared to the WD and LD groups (Fig. 4B, P < 0.05), indicating that increased inflammation could further contribute to lipid metabolism disturbances. Additionally, we observed that AR113 inhibited the expression of both SREBP-1C and P-NF-κB p65 at the protein level, thereby mitigating the inflammatory effects associated with lipid metabolism dysregulation. Knockdown of the bsh1 gene significantly impaired the functional effects of AR113.

A SREBP-1C, GAPDH, P-NF-κB p65, NF-κB p65, and TNF-α protein levels in the liver; B–D Protein expression of liver SREBP-1C, NF-κB p65, and TNF-α. Different letters (a, b, c, and d) indicate significance (P < 0.05), n = 3.

WD causes gut microbiota dysbiosis in mice

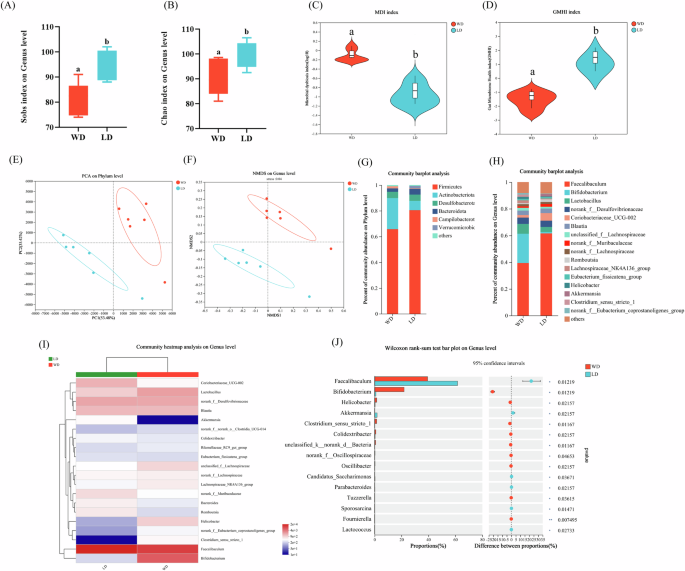

Gut flora is thought to influence host health, and we investigated the effects of different diets on gut microbes in mice. After a 4w dietary intervention, there were significant differences in species richness and diversity between WD and LD mice by 16S rRNA sequencing23, with WD mice accompanied by a higher colony dysbiosis index and a lower colony health index (Fig. 5A–D and S2A–C, P < 0.05). In terms of β-sample, there was a unique microbiota composition between the two groups and at the genus level, WD and LD had four and nine unique species, respectively (Fig. 5E, F and S2D–F, P < 0.05). Analyzing the species composition, at the phylum level, it was mainly composed of Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, Desulfobacterota, and Bacteroidota, and the abundance of Actinobacteriota was lower in the LD group (Fig. 5G, P < 0.05). At the genus level, WD and LD mice had a lower abundance of Akkermansia and Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, respectively (Fig. 5H–J, P < 0.05). That is, LD mice have a higher abundance of beneficial bacteria and a healthier flora structure.

A Shannon index on genus level; B Chao index on genus level; C Microbial dysbiosis index (MDI); D Gut Microbiome Health Index (GMHI); E WD and LD groups Unweighted UniFrac distance-based PCA plots on the phylum level; F Non-metric multidimensional scaling on the genus level; G, H WD and LD groups Relative abundance of gut microbiota on phylum and genus levels; I Community composition heatmap on the genus level; J Wilcoxon rank-sum test bar plot on genus level between the WD and the LD groups. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to examine differences in bacterial composition between the two groups. Different letters (a and b) indicate significance (P < 0.05), n = 6.

AR113 improvement of the structure of the gut microbes in mice with colitis on a Western diet

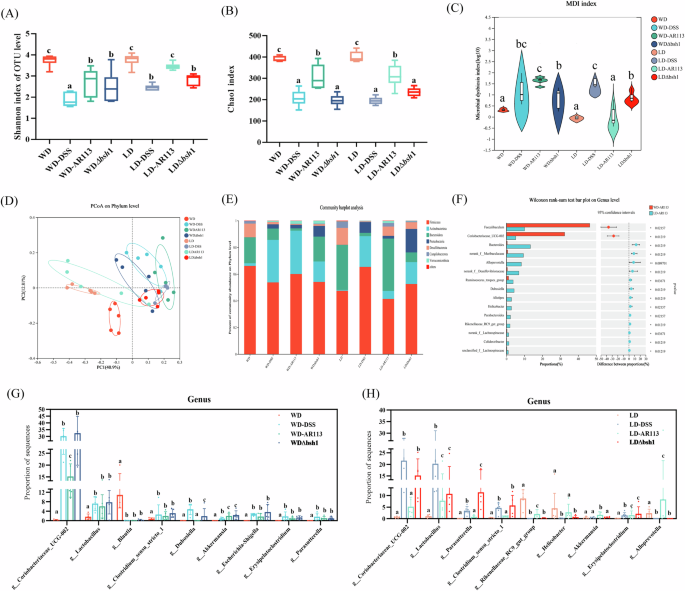

After the DSS intervention, we investigated the effects of AR113 and AR113Δbsh1 on the gut microbial composition of mice. AR113 significantly increased community richness and diversity (Fig. 6A, B and S3A, B, P < 0.05) and showed different unique microbial compositions at the phylum and genus levels, and reduced the colony dysbiosis index compared with the WD-DSS/ LD-DSS group (Fig. 6C, D and S3C, P < 0.05). However, AR113Δbsh1 had limited ability to regulate microbial diversity (Fig. 6A–D).

A Shannon index of OUT level; B Chao index; C Microbial dysbiosis index (MDI); D PCOA (principal co-ordinates analysis) of gut microbiota at the phylum level; E Relative abundance at the phylum level of each group; F Wilcoxon rank-sum test bar plot on genus level between WD-AR113 and LD-AR113 groups; G The relative abundance of dominant flora at the genus level in the WD groups; H The relative abundance of dominant flora at the genus level in the LD groups. Different letters (a, b, and c) indicate significance (P < 0.05), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n = 5.

Differences in colony structure may lead to different disease severity as Lactobacillus, Romboutsia, and Paraclostridium were more abundant and norank_f__Desulfovibrionaceae were less abundant in the LD-DSS group compared to the WD-DSS group (Fig. S3D). The WD-AR113 group had significantly increased Faecalibaculum, Coriobacteriaceae_UCG-002, and lower Bacteroides abundance (Fig. 6F). This change was closely related to dietary structure. To further understand the effects of different dietary treatments on gut microbes, we assessed differences in microbiota composition and relative abundance at the genus level (Fig. 6G, H). We found that both AR113 and AR113Δbsh1 increased the abundance of g__Akkermansia compared to the WD-DSS group (Fig. 6G, P < 0.05) but only AR113 decreased the abundance of g__Coriobacteriaceae_UCG-002. The LD-DSS group significantly increased the relative abundance of g__Coriobacteriaceae_UCG-002, g__Parasutterella, and g__Erysipelatoclostridium decreased the abundance of g__Akkermansia (Fig. 6H, P < 0.05), and similarly, AR113 reversed these changes. (Fig. 6G, H, P < 0.05). However, the intervention effect of AR113Δbsh1 on the intestinal flora was not significantly different from that of the DSS group. In summary, AR113 restored WD and DSS-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis to a certain extent by increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria and decreasing the abundance of harmful bacteria in the intestinal tract, which may contribute to the alleviation of inflammatory responses and lipid metabolism disorders.

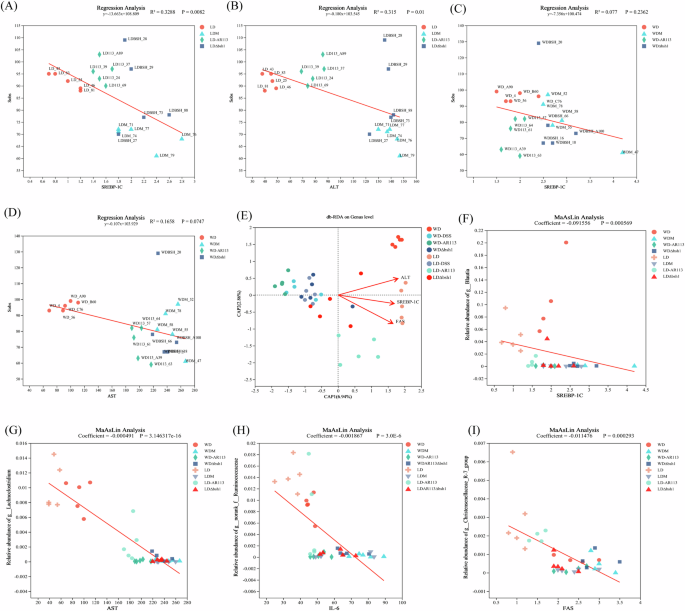

Finally, we mined for correlations between clinical factors and the relative abundance of microbial community species. We found that SREBP-1C, ALT, and AST explained more of the differences in sample community composition in the sobs index in the low-sugar, low-fat diet intervention group (Fig. 7A–D and S3E, F, P < 0.05). ALT, SREBP-1C, and FAS affected the composition of the gut microbiota to a greater extent, and there was a positive correlation between the three. (Fig. 7E, P < 0.05). Multivariate association with linear models (MaAsLin) analysis indicated that SREBP-1C with g__Blautia, AST with g__Lachnoclostridium, IL-6 with g__norank__f__Ruminococcaceae, FAS with g__Christensenellaceae_R-7_group, and ALT with g__Harryflintia were negatively correlated (Fig. 7F–I and S1G, P < 0.05). This suggests that these microorganisms may be involved in hepatic lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Overall, dietary and disease interventions lead to different microbial abundances, but different microbial abundances are in turn strongly associated with indicators of lipid metabolism and inflammation.

A Linear regression analysis of SREBP-1C on the Sobs index in the LD groups; B Linear regression analysis of ALT on the Sobs index in the LD groups; C Linear regression analysis of SREBP-1C on the sobs index in the WD groups; D Linear regression analysis of AST on the sobs index in the WD groups; E db-RDA analysis of SREBP-1C, ALT, and FAS; F–I MaAsLin correlation analysis of SREBP-1C with g__Blautia, AST with g__Lachnoclostridium, IL-6 with g__norank__f__Ruminococcaceae, FAS with g__Christensenellaceae_R-7_group.

Discussion

Possible mutually reinforcing relationship between disorders of lipid metabolism and inflammation10. The gut and liver are connected by a portal vein, and this gut-liver axis is capable of transporting dietary and microbial components and metabolites from the gut to the liver. Exposure of the liver to bacterial components, metabolites, inflammatory factors, and signals significantly affects hepatic immunology and homeostasis in vivo. According to recent studies, bile acids act as pleiotropic signaling molecules that regulate crosstalk between the gut and the liver23,24,25,26. In previous studies, we have demonstrated that AR113 is effective in alleviating colitis caused by Western diet and that the bsh1 gene may play a key role in anti-inflammation27. Therefore, in addition to the preliminary study of the effect of the bsh1 gene on AR113 in alleviating liver-like diseases, the present study aims to reveal whether AR113 can alleviate liver metabolism and injury, and thus liver inflammation, and thus search for targets between lipid metabolism and inflammation.

Diet directly influences microbiota composition and metabolic patterns in the gut, which, in turn, impact the barrier function of intestinal epithelial cells. This dysfunction allows metabolites, toxins, chemokines, and cytokines to pass into the liver via the portal circulation28. However, the metabolites produced by microorganisms are thought to affect the physiological health of the host29. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the cell membrane in intestinal Gram-negative bacteria, can trigger an inflammatory response even in small amounts when released into the circulation, subsequently affecting liver function30. In a mouse model fed a high-fat diet, disruption of the intestinal barrier increases serum levels of LPS and upregulates the expression of various inflammatory factors in hepatocytes, thereby triggering hepatic inflammation5. In patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), there is a significant increase in the abundance of Escherichia spp., which may disrupt the balance of the intestinal microbiota, impair intestinal barrier function, and allow endotoxins to enter the bloodstream, triggering an inflammatory response. This imbalance is thought to contribute to the development of NAFLD31. Bile acids (BAs) are considered microbiota-derived signaling metabolites, and dysregulation of BA-hepatic metabolic interactions is strongly linked to both NAFLD and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)32. Certain secondary bile acids, such as Deoxycholic acid (DCA) and Lithocholic acid (LCA), promote the development of hepatocellular carcinoma when accumulated in the body up to a concentration of 500 μM6.Certain clostridium containing the bile-acid-induced operon (bia) gene can participate in α-dehydroxylation to produce the harmful substance DCA, which inhibits the activation and effector function of CD8+ T cells. Successive accumulation of succinate triggers activation of transmembrane signaling molecule (SUCNR1 protein) in hepatic stellate Cell (HSC), which induces hepatic inflammation33.

Hepatic FXR can maintain the dynamic balance between bile acids and cholesterol by regulating the activity of CYP7A1, which in turn is involved in the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids. Decreased cholesterol levels mean that hepatic FXR is inhibited, at which point CYP7A1 expression is elevated and cholesterol is converted to more bile acids to be stored in the gallbladder, which may lead to impaired hepatic function or cholestasis when the liver synthesizes too much bile acids10. We found that intake of a Western diet resulted in reduced hepatic FXR expression compared to mice on a low-sugar, low-fat diet, yet intervention with colitis further inhibited hepatic FXR activation. In addition, FXR is an upstream receptor for SREBP-1C, and inhibition of SREBP-1C expression suppresses hepatic lipogenesis through activation of small heterodimeric chaperone (SHP)34. However, it is exciting to note that AR113 increased hepatic FXR expression accompanied by a decrease in SREBP-1C, which in turn is involved in the regulation of hepatic bile acid and lipid metabolism and maintenance of normal hepatic function. Excessive accumulation of lipids leads to an imbalance of lipid metabolism17.

Lipid metabolism consists of anabolism and catabolism, a process that is regulated by a variety of transcription factors35. FAS and ACC are essential enzymes that contribute to the process of fatty acid synthesis, whereas PPAR-α is crucial for the regulation of lipid metabolism. Research has demonstrated that PPAR-α agonists can reduce hepatocellular damage and inflammation caused by a high-fat diet, in addition to enhancing insulin sensitivity36. We found that the downstream target gene FAS mRNA expression was consistent with the alteration of SREBP-1C, suggesting that AR113 inhibits the expression and activity of SREBP-1C, and ameliorates fat accumulation and steatosis in the liver by down-regulating FAS and up-regulating the relative expression of PPAR-α gene. In our study, we found that the Western diet-induced lipid metabolism disorders were exacerbated by DSS intervention, and AR113 was able to alleviate the lipid metabolism disorders in colitis mice on the Western diet by regulating fatty acid and bile acid metabolism.

Tumor necrosis factor-a is a pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in many biochemical pathways. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces hepatocyte injury indirectly through the TNF-α– NF-κB signaling pathway14. Prakash et al.37 demonstrated that the expression of SREBP-1C and FAS is stimulated by TNF-α. In contrast, when TNF-α is inhibited, the levels of SREBP-1C and FAS are similarly reduced38. Similarly, increased expression of SREBPs in response to inflammatory stimuli increases hepatic lipid synthesis and uptake, leading to a “second strike” in the liver and promoting the development of MASLD. In addition, SREBP-1C upregulates reactive oxidants, induces the NF-κB inflammatory pathway, and promotes the secretion of inflammatory factors39. In conclusion, there may be an interaction between SREBP-1C and the NF-κB pathway. It was demonstrated that the neddylation (ubiquitination-like modification-associated recombinant protein) inhibitor MLN4924 attenuates high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis by lowering the levels of SREBP-1C protein and triglycerides40. SREBP-1C inhibitors may be a novel approach to combat liver disease41. Our study suggests that the Western diet may exacerbate inflammatory responses by inducing lipid metabolism disorders and increasing SREBP-1C expression, whereas AR113 inhibits SREBP-1C and P-NF-κB p65 expression at the protein level and reduces hepatic inflammatory responses. In addition, lipid metabolism or fatty acid metabolism may be associated with inflammation.

Western diet significantly affects microbial composition, and abnormal fat accumulation and metabolism can lead to an imbalance of the gut microbiota, triggering more chronic metabolic diseases42. In our study, LD mice had healthier colony structures after dietary intervention. Compared with the WD/LD group, the colony diversity index decreased after DSS induction, but the intervention of AR113 restored the richness and diversity of the colonies to a certain extent and altered the colony typing. Coriobacteriaceae UCG-002 belongs to the family of red bugs and produces harmful substances such as phenol and p-cresol which can impair the intestinal barrier function. Meanwhile, Coriobacteriaceae UCG-002, g__Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 was shown to be possibly associated with liver injury parameters43. The g__Parasutterella affects flora and host metabolism and can participate in the maintenance of bile acid homeostasis and cholesterol metabolism44. Akkermansia significantly ameliorated intestinal barrier damage and metabolic disorders induced by a high-fat diet in mice45. Studies have demonstrated that Akkermansia, in combination with metformin, enhances the therapeutic effect of metformin, reduces endotoxin levels in the blood, and attenuates symptoms of liver injury in mice45,46. Escherichia-Shigella is an Aspergillus bacterium that rapidly causes bloody diarrhea and intestinal inflammation, which it induces by penetrating epithelial cells leading to macrophage apoptosis and releasing several pro-inflammatory factors47. The intervention of AR113 increased to some extent the abundance of the beneficial bacteria Akkermansia, g__Parasutterella and decreased the abundance of Coriobacteriaceae UCG-002, g__Clostridium_sensu_stricto __1, g__Escherichia-Shigella abundance, which may be another important reason why AR113 alleviates liver inflammation and lipid metabolism. However, in the Western diet, we found limited effects of AR113 on the gut microbiota. The more lasting effects of long-term intake of the Western diet on the gut flora and the shorter duration of the AR113 intervention may be the reasons for this. On the contrary, AR113Δbsh1 had less effect on the intestinal flora. Similar to previous findings, bsh1 may be critical for AR113 to fulfill its probiotic function. In summary, we propose that the removal of the bsh1 gene could hinder the strain’s ability to provide its initial advantages or to establish itself within the gastrointestinal tract as a result of bile salt stress. Second, BSH regulates the bile acid cycle, and bsh-carrying strains modulate bile acid metabolism and host immunity thereby reducing inflammation.

In this study, the Western diet led to disorders of lipid metabolism and dysbiosis of the gut microflora, which in turn exacerbated the inflammatory response. AR113 reduced hepatic inflammatory factor levels and modulated intestinal microbial diversity by inhibiting the expression of SREBP-1C and P-NF-κB p65, and attenuated the abnormal lipid metabolism and hepatic injury phenotypes in colitis mice on a Western diet. However, none of these changes occurred in AR113Δbsh1, so we hypothesized that bsh1 may AR113 play a key role in ameliorating lipid metabolism disorders. Furthermore, we found a possible correlation between lipid metabolism and inflammation.

Methods

Reagents

Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Aurora, OH, USA). The SREBP-1C antibody was purchased from Affinity Biosciences LTD (Jiangsu, China). TNF-α, GAPDH, and NF-κB antibodies were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co Ltd. (Shanghai, China). P-NF-κB p65 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody was obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), TNF-α, Interleukin (IL)-1β, Interleukin (IL)-6, Hepatic Lipase (HL), Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase (DGAT), and Fatty Acid Synthesis Enzyme (FAS) assay kits were purchased from Tongwei Biotechnology Co Ltd. (Shanghai, China). RIPA, QuickBlock™ Blocking Buffer, and BeyoECL Plus were obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology Co Ltd. (Shanghai, China). PVDF membrane purchased from Ball Corporation (New York, USA).

Diet and strains

Kimchi comes from Xinjiang. Weigh 20 g of kimchi, cut with sterile scissors, and loaded into 180 mL of saline, in a constant temperature shaker at 37 °C, shaking for 30 min at 200 rpm/min. Subsequently, the samples were gradient diluted, and 100 μl of the dilution was spread on an MRS solid medium and incubated in an anaerobic incubator at 37 °C for 48 h, and primer amplification was carried out after observing the colony structure. After observing the colony structure, primers were used to amplify the full-length 16S rDNA, and then the PCR products were sequenced, finally subjected to NCBI comparisons. The experimental flow is shown in Fig. 1A. Lactobacillus plantarum carries four bsh genes (bsh 1, bsh 2, bsh 3, and bsh 4). AR113Δbsh1 is the strain with only the bsh1 gene knocked out. The construction of the bsh1 mutagenesis vector was achieved through the following methodology: Strain AR113 served as the template for PCR amplification, employing the primer sets BSH1up-F and BSH1up-R, BSH1down-F and BSH1down-R, and BSH1gRNA-F and BSH1gRNA-R to generate BSH1up, BSH1down, and BSH1gRNA, respectively (Table S1). Subsequent purification of these fragments facilitated the assembly of BSH1up-down-gRNA (BSH1udg) via homologous recombination. This was followed by the enzymatic digestion of the pHSP01 vector using the restriction endonucleases ApaI and XbaI, and the subsequent ligation of BSH1udg into the linearized pHSP01 vector48. The ligated vectors were then cultured and subjected to screening on selective antibiotic plates. The constructed plasmid, pLdbsh1, was subsequently transformed into AR113 (pLH01) recipient cells via electroporation (Table S2). Screening of the cells was conducted based on antibiotic resistance phenotype, followed by confirmation through PCR amplification and double-stranded sequence analysis. The strain exhibiting the desired sequence identity was successfully constructed and designated as AR113Δbsh148. After removing the AR113 and AR113Δbsh1 strains from the −80 °C refrigerator, single colonies were isolated on MRS solid medium, then centrifuged to remove the supernatant and washed twice with sterile water to resuspend the organisms. The concentration of the bacterial solution used for gavage was 1 × 109 CFU/mL.

Experimental animals and design

Animal studies were reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. The experiment was guided by the Ethics Committee of Tongren Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Approval No. 2021-019-01). Four-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from SPF (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Mice lived in a pathogen-free environment and were fed and watered ad libitum on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle. Mice were given sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injections, IP) for anesthesia before they were sacrificed. The mechanism of action of sodium pentobarbital is mainly through the potentiation of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the central nervous system, which produces anesthetic effects. Blood was collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus into 1.5 ml EP tubes, which were allowed to stand for 30 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min to collect serum. The mice were then sacrificed by neck dissection.

The feed formulation was consistent with our previous experiments27. Sixty-four mice were randomly divided into two groups after one week of acclimatization and were given a Western diet (WD) and a low-sugar, low-fat diet (LD). Consistent with our previous experimental design27, except for the WD and LD groups, which continued to drink normal water, the other groups were treated with dextran sodium sulfate (3% DSS, w/v) for 7 days after four weeks of diet and were gavaged (PBS, AR113, and AR113Δbsh1) on the 5th day of the DSS treatment, with the gavage process lasting for 8 days, and the whole experimental cycle totaled 40 days (n = 8). The bacterial solution used for gavage was 20% of the body weight of the mice. The experimental procedure is shown in Fig. 1B.

Liver and serum biochemical indicators

After the mice were executed, the livers were quickly removed for weighing, photographed, partitioned, and transferred to a −80 °C refrigerator for backup. After removing the liver tissues from the refrigerator, they were accurately weighed, ground in saline, and then centrifuged to extract the supernatant for the determination of total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), glutamate pyruvate aminotransferase (ALT), glutamate oxaloacetic acid aminotransferase (AST), and total protein content. Serum alanine aminotransferase and glutamine aminotransferase levels were measured directly according to the kit instructions and the OD values were determined under an enzyme marker.

Liver histological analysis

The liver tissue was soaked in 10% neutral formalin for 24 h, removed from the fume hood, trimmed to make the tissue flat, and dehydrated in alcohol and paraffin-embedded. Sections were dewaxed to water, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, dehydrated, and sealed for microscopic examination. Liver H&E staining in each group of mice (n = 5) was critically histologically scored according to the NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) scoring system49. Staining was assessed blindly by an experienced pathologist. NAS scoring guidelines are shown in Table 1.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from liver samples using Trizol and subsequently tested for RNA integrity and concentration. Reverse transcription was carried out with HiScript III RT SuperMix (Vazyme, Nanjing, Shanghai) following the protocols provided by the manufacturer for qPCR kits. This was followed by quantitative PCR using SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, Shanghai). The primer composition of the genes involved in the experiment is shown in Table 2.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay

Serum levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were measured using a mouse LPS kit (Tongwei, Shanghai, China). Remove serum samples from the refrigerator at −80 °C and follow the reagent instructions. Optical density (OD) values were measured at 450 nm using a BioTek ELx800 enzyme reader (Biotek, USA). For liver tissue analysis, the liver was homogenized with saline at a specific weight ratio, ground using a steel ball, and then centrifuged to obtain the supernatant. Mouse cholesterol 7-alpha hydroxylase (CYP7A1), diacylglycerolacyltransferase (DGAT), fatty acid synthase (FAS) and hepaticlipase (HL) kits were purchased from Tongwei Biotechnology Co Ltd. (Shanghai, China). This supernatant was subsequently analyzed using an ELISA kit to determine relevant lipase levels, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot

Liver tissue was cryolysed with RIPA, and the supernatant was centrifuged after thorough grinding and the protein concentration was adjusted to 0.5 mg/mL. A sample volume of 10 μl was subjected to SDS-PAGE to separate the different molecular weight proteins and was immediately transferred to a hydrophobic polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Subsequently, the PVDF membrane was rinsed slowly with water and closed in a rapid containment solution for 30 min. After pouring off the sealing solution, the primary antibody was added immediately using TBST wash and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Antibodies SREBP-1C, P-NF-κB p65, NF-κB, TNF-α, and GAPDH were diluted at ratios of 1:2000, 1;1000, 1;2000, 1:1000, and 1:3000, respectively. The primary antibody is collected for subsequent use. The membrane was washed three times with TBST, followed by incubation with secondary antibody for 2–3 h at room temperature. After washing the membrane with TBST with residual secondary antibody (Diluted at 1:2000), protein bands were performed by Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS+. Protein signals were quantified using Fiji (ImageJ) software.

Analysis of gut microbiota by 16s rRNA sequencing

Fecal samples from the day before the mice were sacrificed were collected for microbiota analysis. According to previous method18 the microbiome in the fecal of mice was analyzed by high-throughput sequencing of 16s rRNA genes. Illumina sequencing purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and paired-end sequenced on an Illumina Nextseq2000 platform (San Diego, USA) according to the standard protocols Technology Co. Ltd, (Shanghai, China). The raw sequencing reads were deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (Accession Number: PRJNA1191813)

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed for multiple comparisons using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s test. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS v.22 (IBM Co., New York, NY, USA). We used two-by-two comparisons, and the statistical chart shows the eight groups comparing themselves to each other. Letters a, b, and c are p-values calculated for multiple comparisons. Differences with one of the same labeling letters are considered not significant, and differences with different labeling letters are considered significant. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Responses