Limosilactobacillus reuteri fermented brown rice alleviates anxiety improves cognition and modulates gut microbiota in stressed mice

Introduction

Stress is a complex response that includes both physiological and psychological reactions to an individual’s perception of a threat or challenge, often referred to as a stressor. Although some stress can be advantageous in limited amounts, chronic stress can adversely affect mental and physical well-being, culminating in conditions such as depression and anxiety. The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges stress as a crucial health issue, predicting that stress-linked disorders will be the world’s second primary cause of disability by 2030 https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health. According to WHO, stress and anxiety are major factors in the worldwide disease burden, ranking anxiety disorders as the sixth primary cause of disability globally. Depression and anxiety, two of the most prevalent mental health conditions, are estimated to cost the global economy US$ 1 trillion annually. Research conducted by Baxter et al.1 indicates that individuals with anxiety disorders are more susceptible to experiencing other health issues, such as cardiovascular disease and respiratory disorders. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that exposure to stressors can significantly impact the microbiota, which plays a vital role in regulating the body’s stress response and may contribute to the development of various other health conditions2.

Historically, fermentation was primarily used to preserve and ensure the safety of perishable foods. Over time, it has evolved into a sophisticated process for the production of fermented products with improved sensory qualities, enhanced nutritional value, and health-promoting attributes. This transformation has cemented fermented foods as a staple in many cultural cuisines worldwide3. Globally, fermented foods make up an estimated 30% of the average diet4. A growing body of research highlights the health benefits associated with fermented food consumption3,5,6,7,8. Probiotics, as defined by the WHO, are “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.” Among probiotics, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) stand out for their well-established safety and diverse bioactive properties. This has led to their exploration as potential bioengineering platforms, or cell factories, for producing beneficial compounds9. LAB are commonly used as starter cultures in the fermentation of various foods for both domestic and commercial applications10. The term “psychobiotics” has recently been introduced to describe a new class of probiotics with potential psychiatric applications11. These probiotics are capable of producing neuroactive substances, such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and serotonin, which are known to influence the brain-gut axis. Psychobiotics are thought to reduce cortisol (the “stress hormone”) levels while increasing oxytocin (the “cuddle hormone”), potentially benefiting mental health12,13. The genus Lactobacillus represents a large, diverse group of Gram-positive, non-sporulating, facultatively anaerobic bacteria. Common species include Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus casei, and Limosilactobacillus reuteri14. In recent years, interest in probiotics has surged, driven by rising antibiotic resistance, particularly, in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases, and a growing public preference for natural health-promoting alternatives15.

The gastrointestinal tract hosts a diverse array of microorganisms that maintain mutually beneficial relationships with their human host. Central to this dynamic is the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network linking the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system. This axis enables the coordinated regulation of gastrointestinal functions and has recently emerged as a critical area of study16. Research has shown that this communication pathway not only regulates digestive processes but also influences stress levels, highlighting the intricate interplay between the gut microbiome and overall human health17,18. Stress can disrupt the gut-brain axis through various mechanisms, including alterations in gut microbiota composition, increased intestinal permeability, and immune system dysregulation. These changes can impair the axis’s normal functioning and contribute to the onset of stress-related gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional dyspepsia. Evidence suggests that these gastrointestinal disorders often precede the development of anxiety and depression in many patients19. Studies involving germ-free mice have demonstrated a heightened stress response in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, emphasizing the gut microbiome’s influence on neurophysiology20. Additionally21 stress-induced changes in the gut-brain axis have been linked to immune cell activation in the gut, triggering inflammation and exacerbating conditions like IBS. These findings underscore the critical role of the gut microbiome in shaping both physical and mental health, offering new insights into the relationship between gut health, behavior, and neurophysiological processes.

The connection between gut microbiota and brain function has sparked significant interest, particularly regarding the potential of probiotic or psychobiotics strains to influence cognitive performance and mental health. Dietary interventions, such as consuming probiotics or incorporating probiotic-rich foods, are increasingly recommended for enhancing host health by modulating the composition and activity of gut microbiota22,23,24. For instance, a randomized controlled trial reported significant reductions in anxiety symptoms in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder after eight weeks of supplementation with a blend of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Lactobacillus fermentum25,26,27. Similarly, trials involving Lactobacillus plantarum strains, such as DR7 and P8, demonstrated notable reductions in stress symptoms over eight to twelve weeks, as assessed using the perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)28,29. Furthermore, numerous studies suggest that consuming probiotics fermented grains like brown rice may offer various health benefits30,31. Brown rice is also an excellent source of B vitamins, which are essential for regulating mood. Likewise, a review by Casertano et al. 32 suggested that consumption of psychobiotics and fermented foods, can have positive effects on mental health. Although further research is needed to confirm the findings, there is potential for functional foods, fermented foods, and probiotics or psychobiotics to serve as interventions for alleviating symptoms associated with stress, anxiety, and related disorders. Moreover, in our prior research articles, we have elucidated the benefits of fermented brown rice (FBR) for human well-being through in vitro and ex vivo analysis24,30,33,34. To investigate the potential benefits of psychobiotic-FBR for alleviating stress-related symptoms, we have conducted this comprehensive study using a mouse model of chronic restraint stress. This study involved a variety of behavioral tests to assess anxiety, depression, and cognitive function. We also measured key stress biomarkers, such as corticosterone, IL-6, and TNF-α, as well as neurotransmitters like GABA and serotonin, to explore the underlying mechanisms. In addition, we employed advanced techniques, including metagenomics (16S rRNA) and metabolomics, to investigate stress-induced alterations in metabolites and cecal microbiota. We also analyzed in silico network pharmacology studies to identify primary metabolites and their associated pathways involved in alleviating stress-related disorders. To further understand the pathophysiology of stress and anxiety, we examined the expression of GABA receptors in the prefrontal cortex across normal, stressed, and treated groups, which provided insights into the efficacy of psychobiotics and fermented foods as potential therapies for mental health.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use the psychobiotic Limosilactobacillus reuteri strain, isolated from human breast milk, for the fermentation of brown rice to address chronic stress and its associated disorders. The whole-genome analysis of this strain, which reveals its ability to produce neurotransmitters like GABA24, adds a unique dimension to our research. Our study comprehensively evaluates the effects of FBR on stress-induced anxiety, gut microbiota alterations, and neurotransmitter regulation. Through a combination of behavioral testing, neurotransmitter profiling, serum metabolomics, and metagenomic analysis, we assess the multifaceted impact of FBR. Importantly, our findings show that FBR modulates gut microbiota composition, boosts the production of beneficial metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and restores neurotransmitter balance in a chronic stress model. These results significantly contribute to the development of functional foods aimed at improving mental health, offering fresh insights into the complex relationship between the gut microbiota, metabolites, and the gut-brain axis. Our research highlights the potential of psychobiotic-fermented foods as a promising approach for enhancing psychological resilience and overall well-being.

Results and discussion

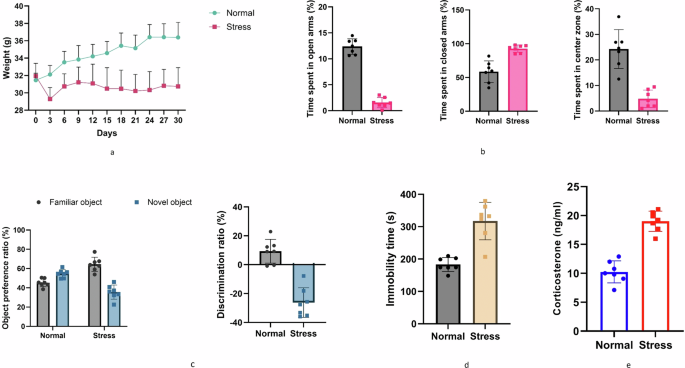

Confirmation of chronic stress induction

Administering chronic restraint stress daily for two weeks effectively induced significant anxiety-related behaviors in EPMT, disrupted cognitive function in NOR test, and elicited depression-related behaviors in the FST. Stressed mice also exhibited a reduction in weight compared to the normal group (Fig. 1a). In the EPMT and NOR, stressed mice spent less time in and made fewer entries into the center and preferred closed arms reflecting heightened anxiety (Fig. 1b, c), compared to the normal group, also, stressed mice were unable to distinguish between the two objects indicating disrupted cognitive function. Additionally, FST showed increased immobility, indicating despair-like behavior (Fig. 1d) along with elevated corticosterone levels (Fig. 1e) confirming chronic stress has the potential to induce anxiety-like behaviors in mice and provides validation for our stress protocol. Numerous studies have established a robust association between stress and the onset of anxiety and its related conditions. This explains the connection between the disruption of the HPA axis, resulting in an excessive release of glucocorticoids (such as corticosterone). This, in turn, triggers biochemical and neurochemical alterations that impact the brain’s intracellular redox status in rodents35.

a Body weight and food take analysis. b Behavior analysis-Elevated plus-maze test (EPMT). c Behavior analysis-Novel object recognition test (NOR). d Behavior analysis-Forced swim test (FST). and e Corticosterone stress hormone analysis.

Psychobiotics FBR significantly improved anxiety-related behavior and cognitive function

Body weight and food intake analysis

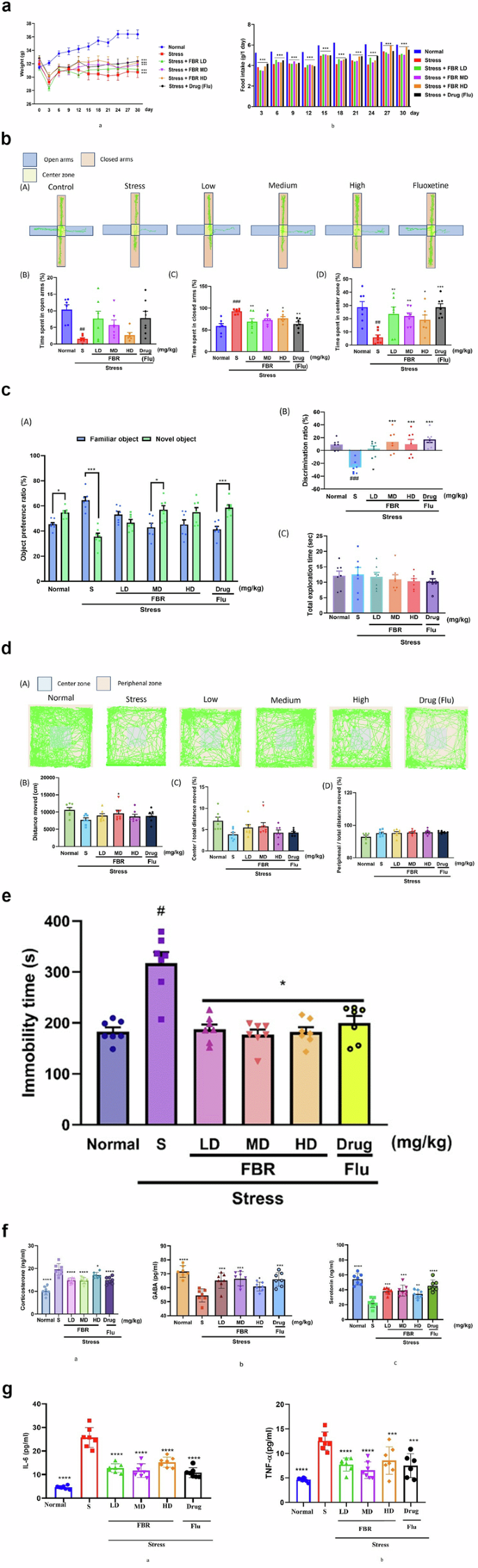

After administering varying doses of FBR (low, medium, and high), enhancements were observed in the body weight index. Notably, the stressed group exhibited the lowest weight. As explained earlier, activation of the HPA axis results in the upregulation of corticosterone, increased metabolic rate, and energy expenditure, which can lead to weight loss, especially when energy intake does not meet the elevated energy demands. Elevated levels of corticosterone may suppress appetite by directly affecting brain regions involved in hunger regulation, such as the hypothalamus, or by altering the levels of hormones that control hunger36. The interventions involving FBR and the drug led to weight improvements, particularly in stressed mice, with the medium and high doses of FBR yielding significant results. However, no notable differences were noted in food intake (Fig. 2a (a, b)). These divergent outcomes in body weight gain underscore the significance of both the dietary regimen and the FBR dosage in investigating the effects of FBR on ICR mice subjected to chronic stress. Therefore, further behavioral analyses were conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the effects of FBR on chronic stress.

a Effects of FBR on the changes of body weight and food intake in the chronic stressed mice. a The change in body weight and b the changes in food intake of mice. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. The represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group). ***p < 0.001 versus the normal group. b Effect of fermented brown rice on anxiety-like behavior in the chronically stressed mice. A tracking area, B The time spent in open arms, C The time spent in close arms, and D The time spent in center zone. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group). ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 versus the normal group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus the stress-only group. c Effect of fermented brown rice on memory deficits in the chronic stressed mice. A Object preference ratio of each object, B Discrimination ratio, and C The total exploration time are represented. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. The comparison between familiar object and novel object using t test (a). The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 (t test); #p < 0.001, versus the normal; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 versus the stress-only group. d Effect of fermented brown rice on locomotion behavior in the chronic stressed mice. A Tracking area, B Distance moved in box, C Distance moved spent in the center zone divided by total distance moved and D Distance moved spent in the periphenal zone divided by total distance moved. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group) *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 versus the stress-only group. e Effect of fermented brown rice on depression in the chronic stressed mice. The immobility time in FST. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. The represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group). *p < 0.05 versus the stress-only group #p < 0.001. f Effect of fermented brown rice on stress hormone corticosterone and neurotransmitter GABA & Serotonin in the chronic stressed mice. a presents effect of fermented brown rice on stress hormone corticosterone, whereas b, c represents effect of fermented brown rice on neurotransmitter GABA & Serotonin in the chronic stressed mice. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 versus the stress-only group. g Effect of fermented brown rice on IL-6 and TNF-α in the chronic stressed mice (a, b). a shows the effect of fermented brown rice on IL-6, while b depicts its effect on TNF-α compared to the control and stressed groups.The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 versus the stress-only group. Normal normal or No stress, FBR Fermented brown rice, Drug (Flu) Fluoxetine, LD Low dose, MD Medium dose, HD High dose, S Stress.

Elevated plus-maze test (EPMT)

The treatment groups of mice demonstrated significant differences in their behavior during EPMT analysis. Particularly, the stressed group spent significantly less time in the open arms and center zone of the maze compared to the normal control and treatment groups. Post hoc analysis further illustrated that chronic stress led to a significant reduction in the time spent in the open arms compared to the normal group (p < 0.01). As demonstrated in Fig. 2b (A-D), the administration of different doses of FBR to the mice displayed noteworthy effects. Specifically, the low and medium doses of FBR led to a reversal in the reduced time spent in the open arms (p < 0.05) and the central zone (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, respectively) of the EPMT. Additionally, these FBR doses significantly reduced the time spent in the closed arms (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, respectively), which had been elevated due to chronic stress. These findings collectively emphasize the anxiolytic-like properties of FBR, as it counteracted the anxiety-inducing effects of chronic stress, thereby restoring more balanced behavior in the EPMT.

Novel object recognition test (NOR)

The intervention with FBR significantly improved the discrimination ratio (%) between familiar and novel objects, with the effect being most pronounced at medium and high doses of FBR (p < 0.001) in the NOR test. This effect contrasted sharply with the stressed group, where the mice were unable to distinguish between the two objects (p < 0.001). Markedly, no significant differences were observed in the total exploration time (in seconds) across the experimental groups. These findings highlight that the improvement in cognitive function observed with FBR treatment was not accompanied by changes in overall exploration behavior. Figure 2c (A-C) presents the results, showing an increase in cognitive discrimination following FBR administration. This suggests that FBR, particularly when administered at medium and high doses, may help alleviate stress-induced cognitive impairments, as evidenced by the results of the novel object recognition test.

Open field test

OFT is used as a prominent behavioral assay within rodent research, serving as a valuable tool to evaluate exploratory and anxiety-related behaviors. This test delves into the complex relationship between rodents’ emotional states and their tendency to seek novelty by evaluating factors such as total distance traveled and the amount of time spent in the center versus the peripheral areas. Functionally, the Open Field Test (OFT) provides insight into the animals’ emotional states, evaluating their tendency to explore unfamiliar areas and their sensitivity to anxiety-inducing stimuli. Typically, a preference for spending more time in the open center of the arena is considered an indicator of lower anxiety, as the center is less protective compared to the peripheral edges. Conversely, a preference for the periphery indicates heightened anxiety. During our analysis, we focused on the frequency of entries made into the center. Noticeably, mice subjected to chronic stress showed a significant decrease in center entries, suggesting increased anxiety-like behavior. In contrast, the FBR-treated group led to a marked improvement, displaying a significant increase in both the time spent and locomotion within the center of the arena. This effect was particularly asserted in the medium dose group (p < 0.05), as depicted in Fig. 2d (A-D). However, it is noteworthy that no significant differences were observed in the ratio of peripheral distance to total distance among the experimental groups. This suggests that while FBR treatment increased center exploration and locomotion, it did not substantially alter the overall mobility patterns of the animals. In summary, the OFT provides valuable insights into how rodents interact with their environment, highlighting the complex dynamics between stress, intervention, and exploratory behavior. The findings emphasize FBR’s potential to modulate anxiety responses, particularly through increased engagement with the center of the arena.

Forced swim test

FST is a pivotal assay frequently employed for assessing the efficacy of antidepressants. In this paradigm, the duration of immobility serves as a key metric, providing insight into the response of the stressed model. Immobility time in the FST is a behavioral marker indicative of helplessness, a central feature of this test. Clearly, the group subjected to chronic stress exhibited a significant increase in immobility duration (p < 0.001). This prolonged immobility period underscores the induction of a helpless-like state, consistent with the established interpretation of this behavioral outcome. In comparison, the normal group and those treated with FBR exhibited different responses. The stressed group showed a significantly longer immobility period compared to the normal and FBR-treated groups, indicating the efficacy of FBR in reducing stress-induced despair-like behavior (p < 0.05). FBR treatment significantly increased the time spent in active swimming while decreasing immobility time (p < 0.05), as illustrated in Fig. 2e. These results suggest that FBR can modulate behavioral responses related to stress-induced helplessness, with the reduction in immobility time and the increase in active swimming indicating potential antidepressant-like effects. This supports the broader utility of the FST in screening compounds with mood-enhancing properties and suggests that FBR may help mitigate stress-related behavioral changes.

Given the positive impact of FBR on behavioral outcomes, additional hormonal analyses were conducted to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of FBR on chronic stress. This will allow us to understand whether FBR can modulate stress responses at the hormonal level, thereby complementing the behavioral improvements observed in the study.

Stress-induced corticosterone levels

The analysis of plasma corticosterone emerged as a critical biomarker, reflecting the complex neuroendocrine response to stress across all six experimental groups. Primarily, the results revealed a significant increase in corticosterone levels due to chronic stress (p < 0.001). This finding underscores the well-established association between stress and heightened glucocorticoid release. However, the FBR intervention effectively counteracted the stress-induced rise in corticosterone levels, significantly restoring them to baseline values. This indicates that FBR treatment plays a role in normalizing the neuroendocrine response to chronic stress. This restorative effect was clearly evident, with a marked difference between the stressed group and the FBR-treated groups, as shown in Fig. 2f (a). These findings highlight FBR’s potential in modulating the stress response, offering valuable insights into its physiological impact within this experimental context.

Detection of neurotransmitter levels

We investigated the levels of two crucial neurotransmitters, GABA and serotonin, by analyzing blood plasma samples from all experimental groups. These neurotransmitters play key roles in regulating mood, cognition, and overall mental well-being. Importantly, the stressed group exhibited a significant decline in both GABA and serotonin levels, indicating a disruption in these essential neuromodulators due to chronic stress. However, a marked change occurred following FBR and drug interventions. The administration of FBR and fluoxetine (Flu) significantly enhanced neurotransmitter levels, with the FBR-treated groups showing the most pronounced improvements, as depicted in Fig. 2f (b, c). This restorative effect highlights FBR’s potential to counteract the neurochemical alterations induced by chronic stress. The observed increase in GABA and other neurotransmitter levels may be attributed to the GABA-producing capabilities of the strain used in this study, which was confirmed in our previous research. Both the strain and the FBR were analyzed for GABA production, along with other beneficial metabolites. These findings suggest that FBR’s impact on neurotransmitter dynamics could be a result of the strain’s ability to synthesize GABA, potentially contributing to the observed neurochemical improvements and supporting the therapeutic potential of FBR in addressing stress-related neurobiological imbalances. The findings highlight a promising avenue for further exploration into FBR’s mechanisms of action and its potential role in modulating neurotransmitter pathways.

Anti-inflammatory activities of FBR

The investigation explored the potential anti-inflammatory effects of FBR, with a focus on two key inflammatory markers: interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). These markers are widely recognized as indicators of inflammation in various diseases and play a significant role in the immune response. Serum samples from both stressed and treatment groups were analyzed to assess the extent of inflammation. The stressed group displayed the highest levels of inflammation, evidenced by elevated IL-6 and TNF-α levels, which align with the established connection between stress and heightened inflammatory responses. In contrast, FBR and drug treatments led to a significant reduction in serum IL-6 and TNF-α levels, indicating an attenuation of the inflammatory response. These results suggest that FBR has the potential to exert anti-inflammatory effects, as illustrated in Fig. 2g. In summary, the study underscores FBR’s ability to modulate the immune response by reducing inflammation, as shown by the decrease in IL-6 and TNF-α levels (Fig. 2g). These findings support the notion that FBR may possess intrinsic anti-inflammatory properties, making it a promising candidate for conditions characterized by chronic inflammation. Further research into FBR’s mechanisms of action related to immune modulation could open new therapeutic possibilities. A clear alignment emerged after conducting a comprehensive series of assessments across behavior, hormone levels, neurotransmitter detection, and inflammatory markers. The results of FBR treatment closely mirrored those observed in the fluoxetine drug treatment groups, highlighting FBR’s potential to improve behaviors associated with stress-related disorders and enhance cognitive function. This connection is especially compelling given the well-established efficacy of pharmacological agents in treating stress-related disorders. However, prolonged use of such drugs is associated with a range of adverse effects, including dizziness, weight gain, vomiting, and headaches. Therefore, our study is based on the hypothesis that incorporating fermented foods, such as FBR, into our diet may help mitigate the potential drawbacks of drug use. This approach holds promise for promoting overall health and well-being. As demonstrated by the earlier analysis, FBR showed significant efficacy in countering chronic stress, as reflected in the reduction of anxiety-related behaviors and the enhancement of key neuromodulators. These promising findings set the stage for further research. To deepen our understanding of FBR’s therapeutic effects, we expanded our investigation to include detailed metabolomic analyses of both fecal and blood samples, as well as in-depth studies on gut metagenomics. This approach allowed us to explore the broader physiological and microbiome-related mechanisms underlying FBR’s beneficial impact.

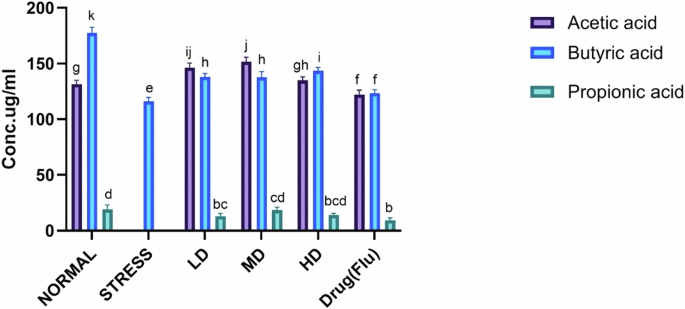

Effect of psychobiotics FBR administration on SCFAs

SCFAs play a key role in the gut-brain axis and are recognized as beneficial metabolites37. They enhance immune system function by promoting cytokine secretion and aiding T-cell differentiation. Additionally, SCFAs protect the integrity of both the intestinal and blood-brain barriers, reducing permeability. They also regulate the HPA axis through vagus nerve signaling38. We analyzed the levels of acetate, propionate, and butyrate in fecal samples. Chronic stress significantly reduced acetic and propionic acid concentrations. Acetic acid, a primary metabolic byproduct of LAB, is known to enhance intestinal epithelial barrier function, supporting gut health and integrity39,40. However, oral administration of FBR notably increased the production of these SCFAs, with butyrate levels surpassing baseline values. Particularly, low and medium doses effectively prevented the reduction of SCFAs in the mouse gut (Fig. 3). The enhancement in acetic and propionic acid levels following FBR interventions highlights the beneficial role of dietary fibers in promoting gut health. Butyrate serves as a key energy source for colonocytes and plays an essential role in maintaining gut homeostasis and restoring barrier integrity during stress41. Its anti-inflammatory and energy-providing properties likely make it a priority metabolite under stress conditions, explaining its continued presence even as other SCFAs were diminished. Chronic stress often induces gut dysbiosis, leading to an imbalance in microbial communities. This disruption typically includes a reduction in beneficial bacterial groups that are key producers of SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. The depletion of these microbes can significantly lower overall SCFA production. However, if butyrate-producing bacteria remain active, butyrate may still be detectable despite the overall decline in SCFAs. These findings highlight the critical role of SCFAs in maintaining gut homeostasis during stress, demonstrating their resilience under adverse conditions. To further investigate the relationship between gut microbiota, and the gut-brain axis, additional gut metagenomics were conducted to elucidate the microbial pathways involved in SCFA production and their broader systemic effects42,43.

The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group). Normal & treatment versus the stress-only group. Alphabets b–k represent significant differences, where a represents the SCFAs absent in the stressed group. Normal: normal or No stress, Stressed only group: Stress, FBR Fermented brown rice, Drug (Flu) Fluoxetine, LD Low dose, MD Medium dose, HD High dose.

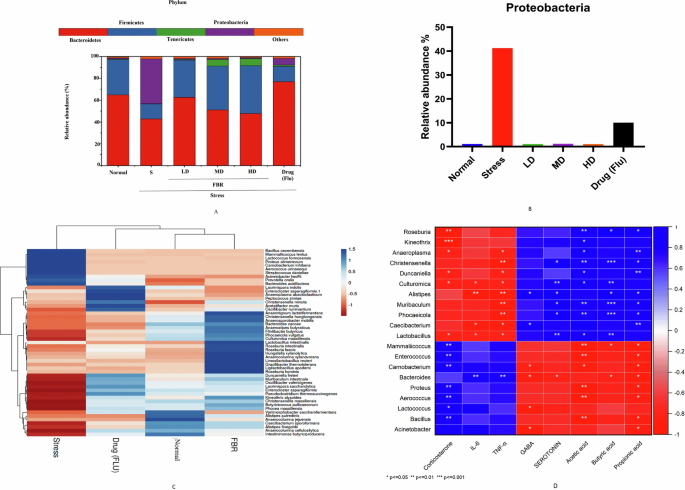

Psychobiotics FBR administration modulated the altered gut microbiota composition of chronically stressed mice

The gut microbiome influences brain function through the gut-brain axis. Chronic stress induces significant changes in gut microbiota composition, often leading to dysbiosis, an imbalance characterized by a reduction in beneficial bacteria and an enhancement of pathogenic microbes. This dysbiosis can exacerbate gut permeability, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction, further influencing the gut-brain axis and contributing to stress-related disorders. Moreover, alterations in microbiota-derived metabolites, such as SCFAs, can modulate the immune response and neuroinflammation, highlighting the complex interaction between the gut microbiome and stress physiology. In the present research, mice subjected to chronic restraint stress were found to have altered gut microbiota compositions compared to normal/control mice44. Consequently, a 16S rRNA (V3–V4) sequencing analysis was performed to examine the diversity of the gut microbiota in mice subjected to chronic stress. The study focused on the gut microbial composition two weeks after stress induction. Particularly, during the early stages of chronic stress, the relative abundance of the Firmicutes phylum significantly decreased (40.46%) compared to the normal group (67.10%). In contrast, the Bacteroidetes phylum showed a marked increase in stressed mice (52.25%) compared to normal (32.66%). Additionally, the Proteobacteria phylum, which was undetected in the normal group (0.0%), was significantly elevated in the stressed group (6.55%). In all analyses conducted thus far, superior efficacy has been observed at low and medium doses of FBR compared to the high dose (1000 mg/kg body weight). As per our understanding, this may be explained by differences in bioavailability and metabolic dynamics. At higher doses, the semi-solid consistency of FBR likely hinders proper dissolution, reducing the absorption of bioactive compounds. This aligns with established pharmacodynamic principles, where intermediate doses often yield optimal effects because excessive doses can saturate biological pathways, leading to diminishing or no additional benefits. Moreover, high doses, such as 1000 mg/kg, may induce metabolic overload or minor adverse effects on metabolic systems, which could counteract therapeutic benefits. At moderate doses, such as 500 mg/kg, bioactive compounds are absorbed and utilized more efficiently, avoiding the metabolic competition and reduced bioavailability seen at higher doses. These findings emphasize the importance of dose optimization in preclinical research, underscoring the need to balance efficacy and safety when establishing appropriate dosages for therapeutic interventions. As low and medium doses of FBR demonstrated superior efficacy in behavioral, corticosterone hormone, neurotransmitter (GABA and serotonin), and inflammatory analyses, further study was conducted to examine the impact of these doses on gut microbiota modulation. At the phylum level, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Tenericutes were the predominant bacterial groups across all seven experimental groups. In the normal group, the relative abundances of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria were 64.93%, 32.30%, and 1.11%, respectively. In contrast, chronic stress resulted in an increase in Proteobacteria (42.21%) and a decrease in Bacteroidetes (42.78%) and Firmicutes (13.88%) at the phylum level. In particular, FBR intervention of all three doses reduced the relative abundance of Proteobacteria (1.18%) to levels comparable to the normal group. Furthermore, the low and medium doses of FBR increased the abundance of Bacteroidetes (62.67% and 51.18%) and Firmicutes (34.08% and 40.1%) at the phylum level. Importantly, the analysis revealed that the low and medium doses of FBR were more effective in modulating the gut microbiota at the phylum level compared to the higher dose. However, in the group treated with the drug, the abundance of Proteobacteria (6.08%) was significantly higher than in the normal group, accompanied by an increase in Bacteroidetes (76.94%) and a decrease in Firmicutes (14.11%) (Fig. 4A). Mainly, FBR treatment resulted in an increase in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio compared to the stressed group. Our findings suggest that Proteobacteria may serve as a microbial signature of dysbiosis in the chronic stress model. These findings are consistent with recent studies45,46, which similarly identified Proteobacteria as a signature of dysbiosis.

A represents Phylum level composition of gut microbiota in different groups, B shows Genus level composition of Proteobacteria in different groups, C is Heat map of gut microbiota composition in different groups at the species level (D). Heatmap of spearman’s correlation between gut microbiota, SCFA’s, and chronic stress-related physiological traits. Normal normal or No stress, FBR Fermented brown rice, Drug (Flu) Fluoxetine, LD Low dose, MD Medium dose, HD High dose.

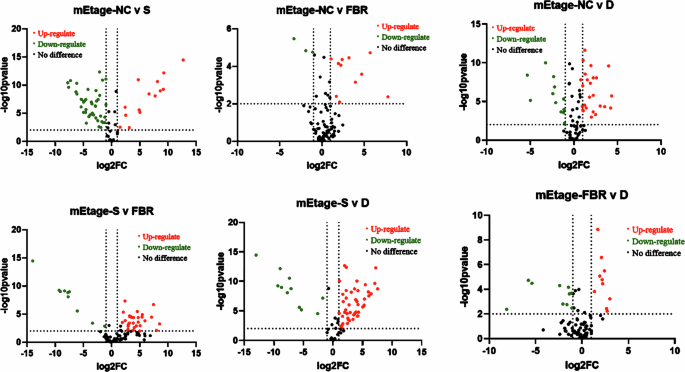

A volcano plot was generated to differentiate the vital bacterial groups among the normal, Stressed, and treatment groups. The plot utilized log fold change and false discovery rate (FDR) values, employing a predetermined cut-off value of 2 (p < 0.05) to identify significant changes. FDR (p < 0.05) was employed to select genera that exhibited significant alterations due to chronic stress (Fig. 5). Chronic stress led to dysbiosis in the gut microbiota, marked by a prominent increase in the relative abundance of pathogenic bacterial genera such as Acinetobacter, Proteus, Enterococcus, Prevotella, Mammalicoccus, Lactococcus, Peptococcus, Canobacterium, Aerococcus, and Bacillus. Conversely, certain genera, including Muribaculum, Culturomica, Kinothrix, Roseburia, Duncaniella, Phocaeicola, Limosilactobacillus, Alistipes, Hungatella, Flinibacter, Oscillibacter, and Phocea, exhibited decreased abundance (Fig. 4A–C).

The volcano plot displays the variation in bacterial prevalence among control, Stressed, FBR-treated, and Drug (FLU) treatment groups. Where red dots indicate upregulations, green represents downregulation, and black represents No significant difference. A value greater than 2 on the y axis indicates statistically significant differences between the groups at a significance level of p < 0.05. Normal normal or No stress, FBR Fermented brown rice, D drug (Fluoxetine), N Normal, S Stress.

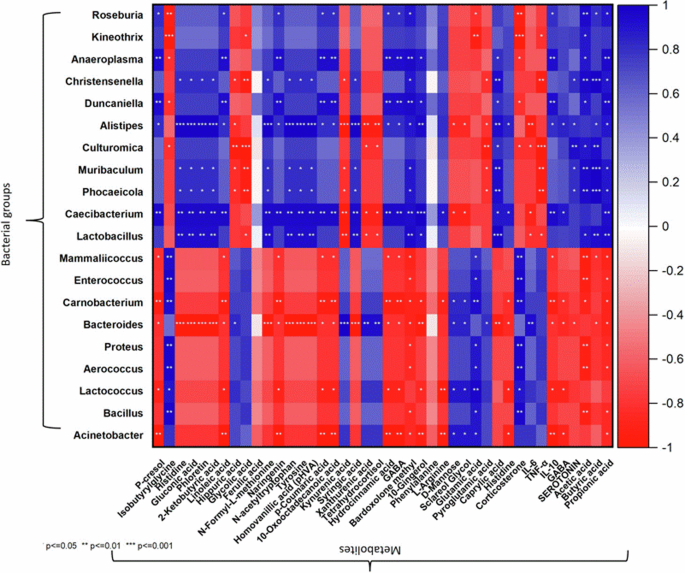

At the same time, FBR treatment reversed the alterations in 10 genera induced by chronic stress. This reversal included a reduction in the abundance of opportunistic pathogens such as Acinetobacter, Enterococcus, Mammalicoccus, Lactococcus, Peptococcus, Canobacterium, Aerococcus, and Bacillus, along with an increase in the abundance of beneficial genera like Muribaculum, Phocaeicola, Alistipes, Kinothrix, Lactobacillus, Duncaniella, Christensenella, and Culturomica. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to explore the relationships between gut microbiota, SCFAs, and physiological traits associated with chronic stress (Fig. 4D). FBR’s impact on genera such as Muribaculum, Phocaeicola, Alistipes, Kinothrix, Lactobacillus, Duncaniella, Christensenella, and Culturomica demonstrated positive correlations with SCFAs and neurotransmitters (GABA and serotonin). In contrast, genera enriched by chronic stress, including Acinetobacter, Proteus, Enterococcus, Prevotella, Mammalicoccus, Lactococcus, Peptococcus, Cyanobacterium, Aerococcus, and Bacillus, showed positive correlations with the stress hormone corticosterone and inflammatory markers (IL-6 and TNF-α), while negatively correlating with SCFAs and neurotransmitters. This analysis highlights the beneficial effects of FBR intervention in modulating the gut microbiota and enhancing health-promoting biomarkers, ultimately mitigating the detrimental impact of chronic stress.

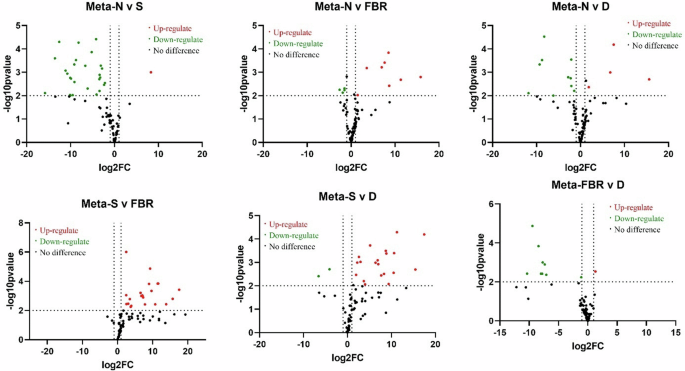

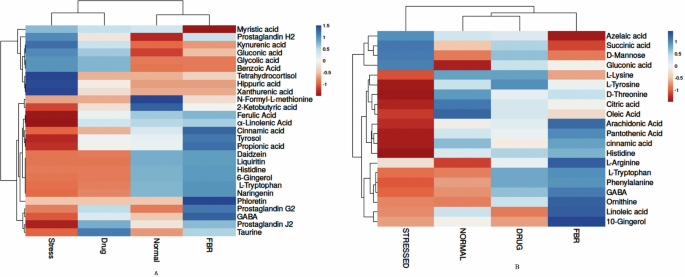

Effect of psychobiotics FBR administration on serum and gut metabolomics

Serum and gut metabolomics provide valuable insights into the biochemical alterations associated with chronic stress. To further investigate the chronic stress-related biomarkers influenced by the gut microbiota, serum metabolomics analysis was performed. This analysis identified various metabolites, including amino acids (AAs) and their derivatives, fatty acids, and organic acids. The stressed group primarily exhibited an enrichment of metabolites associated with glucose metabolism. In contrast, FBR treatment resulted in the enrichment of several amino acids, fatty acids, and their derivatives, including tryptophan, phenylalanine, ornithine, histidine, linoleic acid, palmitic acid, isostearic acid, 3-hydroxyproline, docosapentaenoic acid, 11-eicosatrienoic acid, and arachidonic acid. Compared to the drug-treated group, the FBR-treated group displayed specific amino acids, such as lysine, threonine, citric acid, oleic acid, tyrosine, pyroglutamic acid, glutamine, and selected fatty acids. Our metabolomics findings are consistent with previous research, which highlights a significant increase in glucose metabolism during chronic stress. This alignment underscores the relationship between metabolic alterations and the physiological response to prolonged stress. Studies have shown that in response to chronic stressors, the body activates a range of adaptive mechanisms, including enhanced glucose metabolism. This process is closely tied to the “fight or flight” response, an evolutionary survival mechanism that prepares the body to confront challenges. During stress, various physiological processes are coordinated to ensure a rapid and efficient energy supply, crucial for coping with potential threats47,48. The metabolic shift toward increased glucose utilization represents a critical adaptive mechanism during periods of stress, providing a rapid and readily available energy source to meet the heightened physiological demands. Glucose, a fundamental energy source, is rapidly converted into usable energy to meet heightened physical and cognitive demands. This surge in glucose metabolism is facilitated by complex interactions involving hormones such as cortisol and various signaling pathways. Our study highlights a correlation between stress-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis and the elevation of glucose-related metabolites, offering deeper insights into the intricate relationship between stress, metabolism, and microbial dynamics. These findings enhance our understanding of the interconnected processes underlying chronic stress and their multifaceted impact on metabolic pathways. To identify significant differences in metabolites among the normal, stressed, FBR-treated, and drug-treated groups, log fold change and FDR analyses were conducted with a threshold of 2 (p < 0.05), as depicted in Fig. 6. FBR treatment significantly elevated various microbial metabolites, closely aligning with the metabolic profile of the normal control group. In contrast, the stressed group exhibited increased levels of organic acids, lipid compounds, cortisol derivatives, and glucose-related metabolites, including hippuric acid, xanthurenic acid, tetrahydrocortisol, 2-ketobutyric acid, prostaglandin H2, gluconic acid, and glycolic acid. The FBR-treated group showed enrichment in phenolic compounds, amino acids, neuroactive compounds, and fatty acids, such as ferulic acid, p-cresol, daidzein, histidine, myristic acid, tryptophan, kynurenic acid, taurine, tyrosol, naringenin, and cinnamic acid. Heat map analysis provided a comprehensive overview of metabolites in both serum and fecal samples (Fig. 7A, B). The metabolites enriched by FBR treatment are well-recognized for their beneficial health effects. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the roles of these metabolites and their associated pathways, KEGG-enriched pathway analysis was performed (Supplementary Fig. 2). The analysis revealed that metabolites enriched in the stress group were primarily associated with disease-related pathways. In contrast, the FBR treatment group showed significant enrichment in pathways related to amino acids, fatty acids, secondary metabolites, alkaloids, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and glutathione metabolism. These findings highlight the positive impact of FBR intervention on both gut and serum metabolomic profiles.

The volcano plot displays the variation in blood metabolite prevalence among control, Stressed, FBR-treated and Drug (FLU) treatment groups. Where red dots indicate up-regulations, green represents down-regulation, and black represents No significant difference. A value >2 on the y axis indicates statistically significant differences between the groups at a significance level of p < 0.05. Normal normal or No stress, FBR fermented brown rice, D drug (Fluoxetine), N Normal, S Stress.

A fecal metabolites, B Blood metabolites. Normal normal or No stress, FBR Fermented brown rice.

Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between key differential bacterial genera, metabolites associated with chronic stress, and biomarkers such as stress hormones, IL-6, and SCFAs. Evidently, FBR-enriched bacterial genera showed inverse correlations with metabolites positively linked to chronic stress (Fig. 8). Additionally, these genera exhibited positive correlations with treatment-enriched metabolites associated with health-promoting pathways, as identified through KEGG enrichment analysis. In contrast, bacterial genera enriched under stress conditions demonstrated inverse correlations with metabolites generated by the normal or FBR-treated groups.

Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between key differential bacterial genera and metabolites associated with chronic stress and treatment groups.

Network pharmacology analysis of FBR metabolites to understand its anti-neurodegenerative efficacy

This study investigated the potential pharmacological properties of ten significantly enriched compounds identified in FBR. These compounds were rigorously screened based on their molecular characteristics, with a focus on those demonstrating oral bioavailability values of 30% or higher and drug-likeness values exceeding 0.18 (as presented in Supplementary Table 1). The chemical constituents of FBR, along with their corresponding canonical SMILES representations, are thoroughly detailed in Supplementary Table 2. The principal objective of this study was to unravel the intricate interactions between these compounds and target genes linked to neurodegenerative diseases.

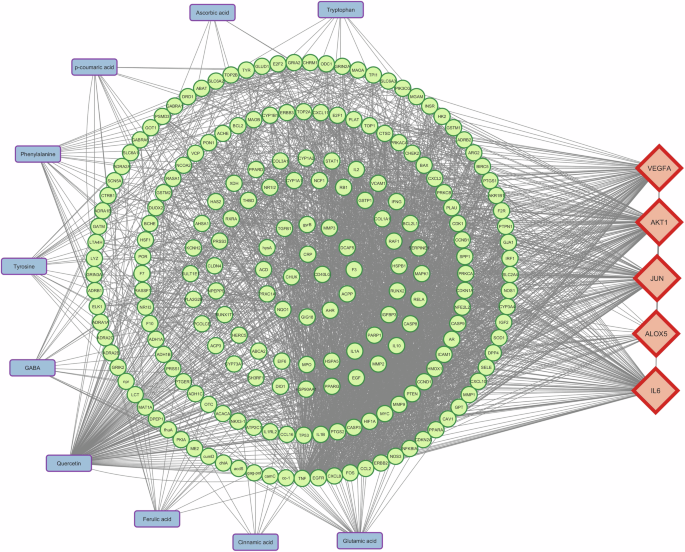

To advance this investigation, a network pharmacology analysis was conducted with precision. A Venn diagram was utilized to compare 94 target genes with the compounds of FBR, curated from the TCMSP, DisGeNET, and GeneCards databases (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3). The interactions between the ten FBR compounds and their respective target genes were visualized using Cytoscape 3.8.0 software. This analysis generated an intricate network consisting of 218 nodes and 300 edges. In this network, blue square nodes represented the ten FBR components, while red box nodes highlighted five key hub genes implicated in neurodegenerative pathways. Additionally, green circular nodes corresponded to 208 genes associated with neurodegenerative diseases, intrinsically linked to the target genes influenced by FBR compounds as illustrated in Fig. 9.

The blue nodes represent the 10 chemical components, and the green circle nodes represent the 208 genes of neurodegenerative disease which correspond to the ingredients’ target-related genes. (The analysis ingredients-target network included 218 nodes and 300 edges).

The analysis highlighted the significance of the top ten components: quercetin, GABA, glutamic acid, phenylalanine, p-coumaric acid, tyrosine, cinnamic acid, tryptophan, ascorbic acid, and ferulic acid. These compounds demonstrated notable affinities for multiple target proteins through their complex interactions. Detailed examination of the interaction network identified five compounds as promising candidates for addressing neurodegenerative disorders. Among them, quercetin emerged as a stand out with 152 interactions, followed by GABA and glutamic acid, each with 49 interactions. Phenylalanine exhibited 25 interactions, and ferulic acid demonstrated 16 interactions, underscoring their potential therapeutic relevance.

To gain deeper insights into the associated pathways, a detailed protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was precisely constructed, complemented by an extensive KEGG pathway analysis, as depicted in Supplementary Figs. 3–5. These figures effectively illustrate the intricate interactions and pathways associated with the identified target genes. In summary, this study thoroughly investigated the dynamic interplay between the bioactive compounds in FBR and the target genes associated with neurodegenerative diseases. The findings suggest that specific components such as quercetin, GABA, glutamic acid, phenylalanine, and ferulic acid hold significant therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative disorders, primarily due to their capacity to interact with multiple target proteins effectively.

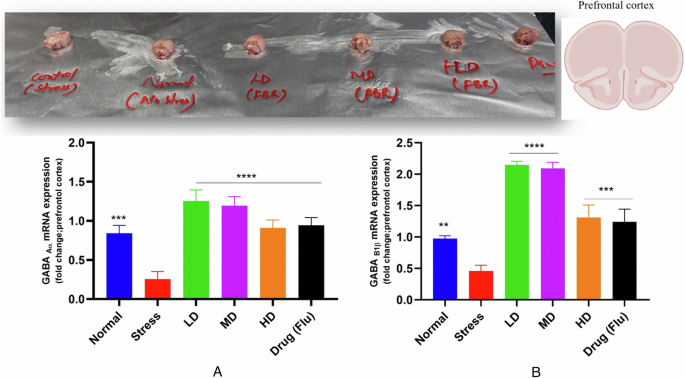

Gene expression analysis revealed low expression of GABA receptors in the prefrontal cortex of stressed mice

Research has highlighted that the balance of GABAergic signaling through the GABAAα2 and GABAB1β receptors in the prefrontal cortex plays a critical role in regulating anxiety, cognitive processes, and mood. Dysfunction in these receptors has been linked to various stress-related behavioral changes, including anxiety and impaired cognition49,50,51. Specifically, alterations in GABAergic signaling through GABAAα2 and GABAB1β receptors can disrupt neuronal inhibitory control, leading to heightened anxiety and cognitive deficits often observed in stress-induced models. As such, these receptors are considered promising targets for therapeutic interventions aimed at alleviating stress-related disorders and enhancing cognitive function.

To explore the potential effects of chronic stress and FBR intervention on these receptors, we collected brain samples and prefrontal cortex of mice from all experimental groups. The objective was to evaluate the expression levels of GABAAα2 and GABAB1β receptors in the prefrontal cortex to determine if chronic stress has a significant impact on their modulation. Additionally, we sought to assess whether the FBR regimen could restore the altered levels of these receptors, potentially normalizing the GABAergic signaling pathways affected by chronic stress. The impact of chronic stress on the expression of GABAAα2 and GABAB1β receptors in the prefrontal cortex of mice was profound, showing a significant reduction compared to the normal group (p < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 10. Specifically, the stress-induced group treated with the vehicle exhibited this reduction in receptor expression, highlighting the detrimental effects of chronic stress on these critical receptors. This observation underscores the dysregulation of GABAergic signaling in the brain under stress conditions, which may contribute to the anxiety and cognitive dysfunction commonly associated with chronic stress. A compelling and promising reversal was observed following the introduction of the FBR intervention. Specifically, the expression of both GABAAα2 and GABAB1β receptors showed a remarkable and statistically significant increase (p < 0.05) when compared to both the stress/vehicle group and the normal/non-stressed group, as illustrated in Fig. 10. This indicates the beneficial impact of FBR on GABAergic signaling and overall health. The gene expression findings align with our previous research, which demonstrated the potential of Limosilactobacillus reuteri as a psychobiotic strain24. Our comprehensive whole-genome analysis revealed the presence of GABA-producing gad genes in this strain, indicating its capacity to enhance GABA synthesis. This comprehensive analysis not only illustrates the complex relationship between chronic stress and receptor expression but also emphasizes the potential of FBR intervention. The ability of FBR to effectively restore and enhance the expression of GABA receptors marks a significant advancement in the promotion of mental well-being. Furthermore, the validation of our selected bacterial strain’s psychobiotic properties, coupled with its capacity to produce GABA, presents a promising avenue for the development of GABA-enriched food products through fermentation. This approach offers a tangible strategy for improving both physical and psychological health, demonstrating the potential of functional foods in addressing stress-related disorders30.

A GABAAα2 receptor expression in the prefrontal cortex (fold change) in the validation experiment. B GABAB1β receptor expression in the prefrontal cortex (fold change) in the validation experiment. The data represent the means ± S.E.M. (n = 7 per group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01,***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 versus the stress-only group. Normal normal or No stress, FBR Fermented brown rice, Drug (Flu) Fluoxetine, LD Low dose, MD Medium dose, HD High dose.

Our study demonstrates that Limosilactobacillus reuteri FBR significantly alleviates anxiety-related behaviors and cognitive impairments in a chronic mild stress (CMS) model using ICR mice. The four-week FBR regimen reversed behavioral despair, reduced corticosterone levels, and improved neurotransmitter balance, specifically GABA and serotonin. Metagenomic analysis of fecal samples and serum metabolomics profiling further revealed that FBR treatment enhances amino acid and energy metabolism, as well as SCFAs. The FBR-treated group exhibited a gut microbiome composition more closely resembling that of the normal group, indicating a beneficial modulation of the gut microbiota. Key bacterial species such as Muribaculum, Phocaeicola, Alistipes, and Lactobacillus were enriched, while the abundance of opportunistic pathogens like Acinetobacter, Proteus, Enterococcus, Prevotella, Mammalicoccus, Lactococcus, Peptococcus, Canobacterium, Aerococcus, and Bacillus was decreased. Additionally, FBR consumption led to favorable changes in serum metabolic biomarkers, reducing harmful metabolites and increasing beneficial ones. The positive modulation of fecal SCFA concentrations, including acetate, butyrate, and propionate, played a pivotal role in gut health and overall well-being. The study also highlighted the potential impact of FBR on gene expressions related to GABA receptors in the brain, suggesting its therapeutic potential for disorders associated with brain relaxation. Additionally, our network pharmacology analysis identified among the top ten FBR bioactive compounds quercetin, GABA, glutamic acid, phenylalanine, and ferulic acid exhibits significant therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative disorders due to their multifaceted interactions with key protein targets. In summary, FBR emerges as a promising psychobiotic with multifaceted benefits in ameliorating chronic stress, anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment. These effects are intricately linked to the modulation of the gut microbiota and their metabolites, neurotransmitter balance, and metabolic markers. Further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and optimize dosing strategies, but these findings pave the way for future therapeutic interventions promoting mental well-being.

Given the global prevalence of anxiety and depression, future research should focus on delineating the precise mechanisms by which psychobiotic-fermented grains exert their effects. Areas for further study include identifying specific bacterial strains and metabolites responsible for observed benefits, optimizing fermentation conditions to maximize therapeutic efficacy, and conducting large-scale human clinical trials to establish dosage guidelines and long-term safety. Investigating the role of dietary fiber in synergistically enhancing psychobiotic effects and exploring personalized nutrition strategies based on individual gut microbiota profiles could further advance this field. These directions have the potential to transform psychobiotic-fermented grains into accessible, functional foods tailored to improve mental-health outcomes globally.

Materials and methods

Probiotic strain used in the study

The LAB Limosilactobacillus reuteri (L. reuteri) used in this study was obtained from the Department of Food Science and Biotechnology at Kangwon National University in South Korea. The bacterial strain was chosen because it has demonstrated great fermentation efficiency in our previous studies30,33. The bacteria stock culture was maintained at −80 °C in MRS broth (Difco) containing 20% glycerol (v/v) for further analysis.

Brown rice sample

Brown rice (BR) sample was purchased from a nearby grain market in Chuncheon, South Korea. Later BR sample is grounded into powder using an electric mill (Hanil electric co., Ltd., South Korea) and filtered through mesh size 40. The samples were kept at −20 °C for further research analysis.

FBR preparation

Sterilized brown rice powder was dissolved in distilled water to prepare the growth medium. The medium was autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min before inoculation with LAB. A fermentation related bacterial strain, Limosilactobacillus reuteri, was then transferred from a 12-hour (overnight) culture into 100 mL of the autoclaved growth medium. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C with 150 rpm agitation for 48 h. After 48 h of fermentation, the resulting FBR or synbiotic sample was freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C for future research.

Experimental animals

This study followed the guidelines established by the UK, EU, and US Animal Research Reporting In Vivo Experiment. It was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Kangwon National University, South Korea (Approval no. KW-210906-1). A total of 42, -week-old male ICR mice (30–35 g) were procured from Orient Bio (Gyeonggi-do, Korea). The mice were housed in a controlled environment at the Kangwon National University Laboratory Animal Center under a 12-hour light/dark cycle, a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C, and a relative humidity of 55 ± 5%. They were kept in ventilated cages with continuous access to a standard chow diet and water ad libitum. Following a one-week acclimatization period, the mice were randomly assigned into six groups, with seven mice per group (n = 42) for the duration of the experiment.

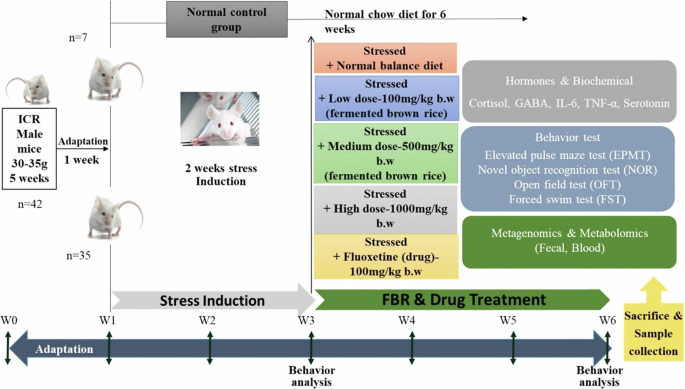

Experimental workflow

Figure 11 depicts the scheduling of experimental procedures. Normal group (Normal) contains non-stressed mice with balanced food and water ad libitum. This group of mice were kept in their living cages without being disturbed. The chronic stress procedure was carried out daily for 14 days to induce stress. After confirmation of anxiety, animals were divided into five groups based on the supplementary diet received during the 21 days. Five experimental groups other than normal/control were assigned: Chronically stressed (stress/vehicle), three stressed groups with candidate FBR (low-100 mg/kg BW, medium-500 mg/kg BW and high dose-1000 mg/kg BW) supplementation, FBR doses were selected based on literature review, toxicity, therapeutic effects, and prior experimental data. The high dose corresponds to the maximum concentration we have tested (1000 mg/mL) in vitro, remaining non-lethal (data not shown here). The medium dose is expected to be effective in vivo based on in vitro cytotoxicity and biological activity, while the low dose serves as a baseline and allows comparison with the drug Fluoxetine. These doses align with preclinical protocols for assessing dose-dependent responses, behavioral changes, and stress markers, providing a comprehensive evaluation of psychobiotics FBR for stress and anxiety.The fifth group in this study is stressed group with drug fluoxetine supplementation (100 mg/kg, BW). Mice were randomly assigned to groups (n = 7) and perorally gavaged with candidate FBR and drug. The mice were administered the candidate FBR and fluoxetine (drug) via oral gavage once daily for three weeks. Every day, freeze-dried FBR samples and fluoxetine were freshly diluted in 300 µl of saline as per the concentrations. Vehicle mice were gavaged with only 300 µl of saline solution per day. A disposable 1 ml syringe (Orient Bio, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) with a stainless-steel cannula (Orient Bio, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) was used for the peroral gavage. The mouse was gently restrained by holding the neck and back. The cannula was carefully inserted into the side of the mouth, positioned alongside the tongue, and guided downward to bypass the tongue. The contents were then slowly and directly injected into the stomach. Behavioral assessments were carried out on the second and fifth weeks to confirm stress induction and treatment using the Elevated plus maze test (EPMT), Open field test (OFT), Forced swim test (FST), and NOR (novel object recognition). Mice Feces samples were collected on the first day, the 14th day following stress induction, and the 35th day following treatment. The feces were stored at −80 °C until analysis. On the 36th day, the mice were anesthetized with ether and euthanized by cervical dislocation, and blood was collected. Plasma was isolated and stored at −80 °C after being pretreated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) during blood collection for corticosterone, serotonin, GABA, IL-6 and TNL-α detection.

Depicts the schedule of experimental procedures.

CMS induction procedure

Two methods were used for stress induction: Immobilization for 2 h/day with subsequent exposure to electric foot shocks52. Seven mice at a time were tested for restrained stress in a stainless cage; the mice were fixed and unable to move (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The mice were subjected to 2 min of electric foot shock stress at 0.5 mA, 1 s with 10 s intervals (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Stressed mice were chronically exposed to identical stressors once a day for two weeks, while the normal control group was left undisturbed.

Body weight and food intake analysis

The mice’s food intake and body weight were recorded manually over 30 days at three days intervals. Before and after a feeding period, the amount of food consumed was weighed and calculated53.

Behavioral analysis

Elevated plus-maze test

The standard method for assessing the anxiolytic-like effects was EPMT. The EPMT apparatus had two open arms and two closed arms, each measuring 60 cm in length, 12 cm in width, and 40 cm in height. The apparatus was placed 100 cm above the ground. The 12-by-12-centimeter central platform served as the link between the arms. Mice were placed in the center of the maze, facing one of the closed arms, and given five minutes to explore. An arm was considered entered when all four paws crossed the dividing line. Using the video tracking program Viewer 3.0, the percentage of time spent in each arm was examined (Biobserve, Bonn, Germany). To eliminate olfactory cues, the maze was cleaned with ethanol following each test54.

Novel object recognition test

The NOR test was conducted to assess the cognitive abilities of the mice using a rectangular, black container measuring 40 cm in height, width, and length. During the habituation period, mice were allowed two days and a total of ten minutes to explore the box. On the third day, the mice were placed in the center of the box with two identical objects positioned 5 cm from the walls, and were given 10 min to investigate and demonstrate their object preference. After 24 h, the mice were returned to the center of the box for five minutes, with one of the original objects replaced by a novel object. In order to calculate the preference ratio for each object and the discrimination index, the ratio of exploration time and the time spent engaging in exploratory behaviors, such as contact, sniffing, and licking, to each object (novel object, Tnovel; familiar object, Tfamiliar), was recorded. Calculations were made to determine the discrimination index and the preference ratio for each item using formula = (Tnovel–Tfamiliar)/(Tnovel + Tfamiliar) × 10055.

Forced swim test

In the FST, individual mice were gently inserted into a Plexiglas cylinder (h × w 30 × 18 cm) that was filled with 30 cm of water at 25 ± 1 °C of temperature. The investigators, unaware of the group assignments, measured and recorded the mice’s immobility and struggling behavior throughout the 6-minute swim session. Immobility was defined as when a mouse floated without struggling, making only the minimal movements necessary to keep its head above the water. Whereas, struggling was defined as making vigorous movements with the forepaws to break the water56.

Open field test

OFT was used to assess the anxiety and spontaneous locomotion of mice. For 30 min, the mice were left to explore the center of a rectangular black box (l × w × h) 40 × 40 × 40 cm. The total ambulatory distance was calculated using the video tracking software Viewer 3.0 (Biobserve, Bonn, Germany). In order to score the entire area, the time traveled through a virtual central zone that was set at 50% of the distance from the edges. Following each test, the test box was cleaned with ethanol57.

Biochemical measurements

Corticosterone (the stress hormone), IL-6, TNF-α, and neurotransmitters like GABA and serotonin were measured in the plasma samples of different mice groups. Samples (blood/plasma) were examined using the Competitive EIA ELISA Kits for Mouse GABA (E4456-100, Biovision, Korea) and Serotonin (E4294-100, Biovision, Korea), Corticosterone (KGE009, R&D Systems, Korea), TNF-α (88-7346-22 ELISA Kit, Invitrogen, Korea, and IL-6 ELISA kit (K4144-100, Biovision, Korea) in accordance with the Kit’s instructions.

Metagenomics analysis using 16S rRNA sequencing

Fecal samples were collected on the first day, the 14th day following stress induction, and at the end of the treatment period. Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, South Korea) performed the 16S rRNA metagenomic sequencing (V3-V4 region) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Illumina), using the Herculase II Fusion DNA Polymerase Nextera XT Index Kit V258. In summary, fecal genomic DNA was extracted, quality controlled, randomly fragmented, and then ligated with 5’ and 3’ adapters for sequence library construction. The prepared library was sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform, and the raw data were converted to FASTQ format. To summarize the taxonomic distribution of OTUs, these libraries were analyzed, and the results were used to estimate the relative abundances of microbiota at various levels.

MicFunPred was used to predict the metagenomic KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) functional profiles (http://micfunpred.microdm.net.in/).

Short-chain fatty-acid analysis

In all groups, we measured the three major SCFAs in feces: acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid, using the protocol previously described by Pan and colleagues with some modifications59. Approximately 0.2 g of feces was placed in a 15-mL centrifuge tube, and 10 mL of water was added to dissolve the sample. The mixture was oscillated for 2 min, then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter into a clean 15-mL centrifuge tube. About 2.0 mL of the filtered sample was mixed with 0.2 mL of a 50% sulfuric acid solution and 2.0 mL of ether, then oscillated 30 times, centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm, and refrigerated for 30 min at 4 °C. The upper ether layer was then subjected to GC/MS (Agilent, USA) analysis on a 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm TG WAX column. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 0.8 mL/min in the GC-MS program. The injection port temperature was set to 200 °C, and the initial column temperature was 120 °C. The temperature was then increased to 150 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min, followed by an increase to 200 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, and held at 200 °C for 2 min.

UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS untargeted metabolomics for metabolites detection in plasma and fecal samples

Blood was collected from behaviorally validated adult mice via cardiac puncture in Microvette® tubes (Molecular devices, Busan, South Korea). The tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 min at room temperature to extract the serum. Serum samples (200 µl) were vortexed for 2 h at room temperature with 70% methanol (200 µl). After centrifuging the mixture at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, 4 °C, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane filter for metabolomics analysis using UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS (AB SCIEX X500R Q-TOF).

At weeks 0, 2, and 6, mice feces were collected and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. A 100 mg sample was spiked with 50 µL of 5 gmL−1 chlorpropamide and extracted into 950 µL of methanol by thorough mixing on a vortex mixer, followed by 10 min of sonication. After centrifuging the mixture at 12,000 g for 10 min, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane filter for UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS analysis. Analysis was performed using our previous protocol60. Metabolites were identified by comparing retention time (RT) and UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS data with spectral literature evidence and crosschecked with spectral libraries, i.e., XCMS Online (Metlin) (https://metlin.scripps.edu) and Metabolomics Workbench (https//www.metabolomicsworkbench.org)61.

Network pharmacology analysis

To gather screening information on target genes related to stress-related disorders and memory impairment, we consulted two databases DisGeNET and GeneCards. DisGeNET is a platform that integrates human diseases, genes, and experimental research62, while GeneCards is a comprehensive database that incorporates genomics, proteomics, genetics, clinical data, and transcriptomics63. We then imported the relevant bioactive metabolites from L.reuteri FBR and their interacting target genes into StringApp in Cytoscape version 3.8.0 to explore their pharmacological mechanism and construct a final PPI network based on draft network data64. We set the species to “Homo sapiens” and used a medium confidence score of 0.700 to ensure the reliability of our analysis. The Network Analyzer module in Cytoscape was used to validate the network65. To verify the identified genes associated with the target diseases, we cross-referenced them with the STITCH v5.0 server66.

The study utilized components derived from FBR to target genes associated with stress-related disorders, focusing on their functions and signaling pathways. The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) system database was used to analyze the functional annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment of proteins. The target proteins were analyzed in terms of their involvement in biological processes, cellular components (CC), molecular function (MF), and KEGG pathways. Using Cytoscape version 3.8.0 software, a network was constructed to show the interaction between the ingredients, targets, pathways, diseases, and components involved. The nodes in the network represent the components, diseases, targets, pathways, while the edges illustrate the interactions between these nodes67.

To investigate further, the tertiary structures of the hub proteins and chemical compounds were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank https://www.rcsb.org/ and DrugBank https://go.drugbank.com/, respectively. Molecular docking studies were carried out using AutoDock Vina 4.2.668 to evaluate the binding interactions between the hub proteins and ligands. The AMBER force field was employed as the scoring function to determine the free energy of interaction between the receptor and ligand molecules69. The Discovery Studio Visualizer 2017 was utilized for the visualization of the docked complex. The most potent inhibitor was identified based on the binding score, as well as hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interactions, for the treatment of stress-related disorders.

Expression analysis of GABA receptors in the prefrontal cortex

In the validation experiment, we assessed the expression levels of GABAAα2 and GABAB1β receptors in the prefrontal cortex of mice. Tissue homogenization was performed using high-speed shaking with a 1 mm stainless-steel bead in 1 ml of QIAzol lysis reagent. Following chloroform addition, RNA was isolated from the aqueous phase via centrifugation and purified using the miRNeasy Mini Kit. Residual DNA was removed with Turbo DNase (Invitrogen), and RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using ReadyScript cDNA Synthesis Mix (Sigma-Aldrich). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was conducted in triplicate with SYBR Green, using β-actin (ACTB) as the housekeeping gene. Receptor Primer sequences used in our study were: GABAAα2: Forward, GGAAGCTACGCTTACACAACC; Reverse, CATCGGGAGCAACCTGAA. GABAB1β: Forward, CGCACCCCTCCTCAGAAC; Reverse, GTCCTCCAGCGCCATCTC. ACTB: Forward, ATGCTCCCCGGGCTGTAT; Reverse, CATAGGAGTCCTTCTGACCCATTC. This precise methodology ensured reliable quantification of receptor gene expressions70.

Statistical analysis

OriginPro 2022 was used to analyze the data (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). The results were presented as the mean, standard deviation of at least triplicate analyses determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test at the figures by *p < 0.05,**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 significance level. The FDR at p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for volcano plots. The Clustvis online platform was used to create heat maps (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/). The GABA receptor gene expression data was initially subjected to the ΔΔ CT and Fold values algorithm, which measured relative differential expression. Subsequently, a non-parametric approach was employed to analyze the data, utilizing the Kruskal-Wallis test for overall comparison and the Nemenyi post hoc test for further pairwise comparisons. Data analysis was also performed using GraphPad Prism software version 10, developed by GraphPad Software Inc., located in La Jolla, CA, USA.

Responses