Lauric-α-linolenic lipids modulate gut microbiota, preventing obesity, insulin resistance and inflammation in high-fat diet mice

Introduction

Prolonged consumption of a high-fat diet (HFD) is a primary contributor to obesity and also plays a key role in related metabolic diseases such as insulin resistance (IR)1,2. On the other hand, IR may further lead to liver dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and dysregulation of glucose and lipid metabolism3,4,5. For instance, ectopic lipid deposition is associated with IR, which is characterized by increased hepatic glucose output and decreased glucose uptake in peripheral tissues such as the liver and muscle4,6. Growing evidence indicates that gut microbiota is closely linked to obesity, IR, and other metabolic syndromes induced by an HFD7,8. Intestinal microbiota can exert both positive and negative effects on the host by regulating energy homeostasis, intestinal permeability, inflammation, and immune responses9. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are a group of metabolites produced by bacteria, primarily generated by the gut microbiota through the fermentation of indigestible dietary components. They serve not only as energy sources but also as signaling molecules6,10. SCFA has been proven to be an important mediator for intestinal microbiota to intervene in the body’s health. SCFA stimulates SCFA receptors in peripheral tissues, transmits signals, and produces health effects such as inhibiting lipid accumulation and anti-inflammatory effects8,11. Emerging evidence suggests that SCFA stimulates the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) by enteroendocrine cells (e.g., L-cells), which can reduce food intake and influence energy metabolism12,13. Thus, the gut microbiota and gut microbiome (such as SCFA) may be a promising target for improving obesity and IR.

Recent studies have indicated that medium- and long-chain structured lipids (MLCTs) are among the dietary approaches for health management14,15. Structural lipids are produced by artificial modification of the glycerol backbone. Nevertheless, MLCT consists of a glycerol molecule that contains medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA, C8-C12) and long-chain fatty acids (LCFA, C14-C22)16. MLCT may offer the nutritional functions and metabolic advantages of both long-chain triglycerides (LCTs) and medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), including the supply of essential fatty acids, rapid oxidation, modulation of gut microbiota, and improvement of IR, while also addressing their deficiencies14,17,18. α-Linolenic acid (ALA) is classified as an LCFA. Flaxseed oil (FO), which is high in ALA, has been demonstrated to enhance liver steatosis and IR in mice by altering the specific localization of ALA and n-3 LCFAs within the liver lipid distribution. Additionally, it promotes the insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of the liver insulin receptor-1 (IRS-1) at tyrosine 632 and protein kinase B19,20. Lauric acid (La, C12) is an MCFA that improves obesity, IR, glucolipid metabolism, gut microbes, and inflammation21,22,23. Therefore, glycerides synthesized with LA and FO could be potential functional MLCTs. Our previous study found that the insertion of La into FO could alter microstructure and thermo-oxidative stabilization16. Theoretically, this specific triglyceride structure (TAG) could offer potential health benefits. However, the evidence connecting the microbiota to these health benefits remains insufficient.

In this study, lauric acid-α-linolenic acid structured lipids (ALSL) were utilized for the first time at an additive dose of 1500 mg/kg in mice on an HFD. Additionally, the effects of ALSL and a physical mixture (PM) with similar fatty acid ratios were compared regarding HFD-induced visceral fat deposition, hyperlipidemia, IR, and systemic inflammation were compared. Furthermore, the study analyzed how ALSL and PM influence gut microbiota composition and SCFA levels, revealing the interaction between circulating SCFA and IR. This study aimed to explore the physiological benefits and potential mechanisms of ALSL supporting the use of ALSL-structured lipids in health-oriented foods.

Results

ALSL supplementation prevents HFD-induced obesity in mice

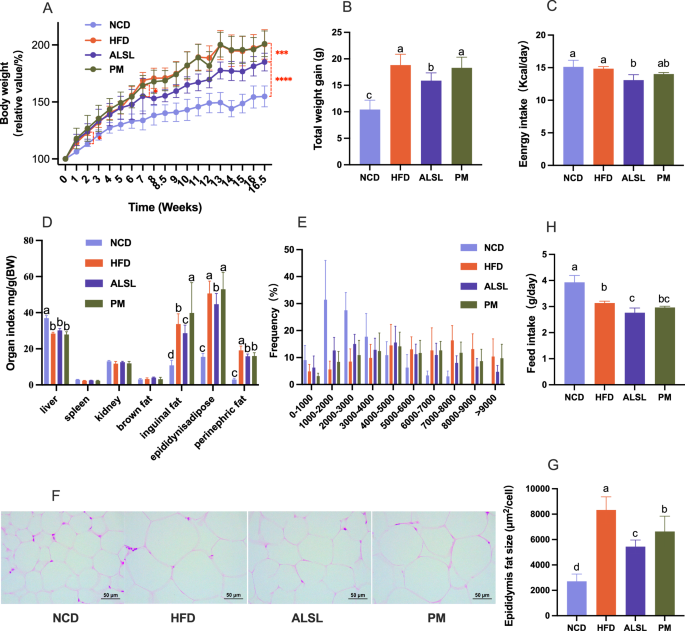

During the total feeding period, there were 16 weeks, there was no significant difference in body weight between groups of mice at baseline (p > 0. 05, Fig. 1A). After 2th weeks, the body weight of the high-dietary feeding group and high-dietary feeding group (HFD, ALSL, PM) was significantly increased compared to the NCD group. From the 8th week to the end of the feeding period, the total weight gain and the percentage of body weight of the mice supplemented with ALSL (p < 0.05, Fig. 1A, B) were clearly lower than those of the HFD and PM groups, indicating that ALSL markedly improved the weight gain induced by the HFD. This may be related to energy intake (Fig. 1C) and feed intake (Fig. 1H), as ALSL greatly reduced daily energy and feed intake compared to HFD, and tended to decrease compared to PM (Fig. 1C, H). Meanwhile, inguinal, epididymal, and perirenal fat accumulation was notably increased in the FHD group (Fig. 1D), whereas ALSL treatment remarkably reduced inguinal, epididymal, and perirenal fat deposition. Similar results were obtained based on the results of H&E staining of epididymal fat (Fig. 1F) and the distribution and size of epididymal adipocytes (Fig. 1E, G), which were dramatically larger in the HFD group compared to the NCD group, and ALSL sharply diminished the size of epididymal adipocytes. Interestingly, although PM did not reduce fat accumulation in the epididymis, it was able to shrink the size of epididymal fat cells considerably. In addition, ALSL inhibited hepatic fat accumulation to a greater extent than PM, and H&E staining of the liver showed that vacuoles were substantially minimized in ALSL (Fig. 3M). Taken together, these results showed that ALSL ameliorates HFD-induced weight gain and visceral fat accumulation.

A Relative body weight curves of different groups of mice (relative body weight% = body weight per mice/initial body weight at start of experiment*100%, n = 12). B Total body weight gain at week 16.5. C Mean daily energy intake. D Organ weight index of the mice (Index = organ weight/weight per mice). E The frequency of epididymal adipocyte size in (F). F Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of epididymal fat. G Area of epididymal fat, (scale bar, 50 μm). Adipocyte size in the panel was estimated using ImageJ software (10 different fields of view were calculated for each H&E staining image). H Feed intake. The number of mice tested in A–D and H was n = 12, and the number of mice tested in E–G was n = 8. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, a, b, c and d means significant difference (p < 0.05).

ALSL improves HFD-induced IR and disorder of lipid metabolism in mice

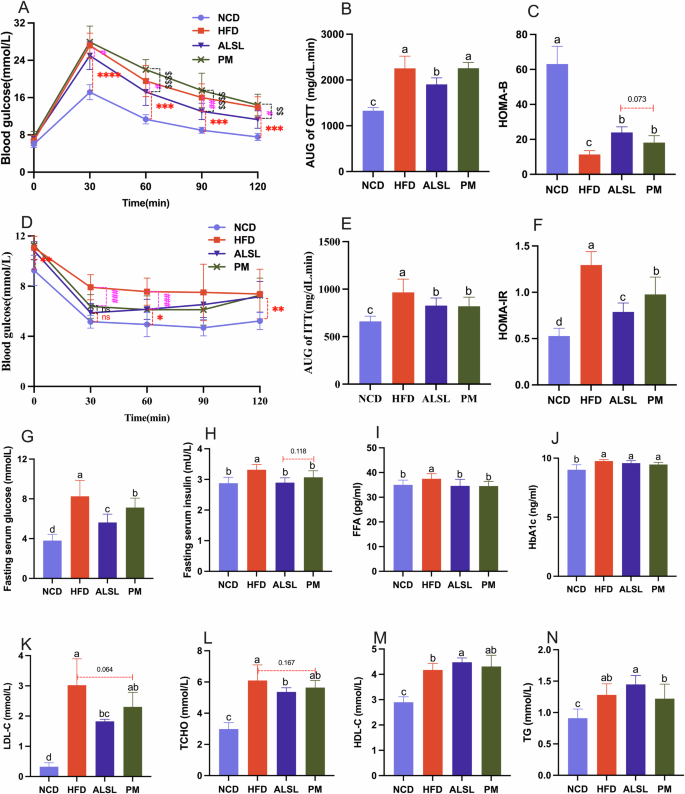

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IGTT) and ITT were performed, and changes in glucose concentration over 120 min were observed as presented in Fig. 2A, D. This implies that HFD triggered lower glucose tolerance (GTT) and insulin sensitivity, and that IR occurred. The area under the glucose curve (AUC) was determined based on the glucose profile (Fig. 2B, E), and the intervention of ALSL greatly improved their GTT (p < 0.05) and increased their insulin sensitivity (p < 0.05) compared to the HFD group. It is interesting to note that PM notably improved their insulin sensitivity (p < 0.05), but did not improve their GTT (p > 0.05). This is consistent with the phenomena that fasting serum glucose and insulin levels were also significantly reduced by ALSL and PM compared with FHD (Fig. 2G, H). Besides, the serum glucose level of ALSL was much smaller than that of PM, which demonstrated that the ability of ALSL to change the serum glucose level was stronger than that of PM. However, the ALSL and PM interventions both altered the HFD-induced increase in HOMA-IR and decrease in HOMA-B considerably, and the ameliorative effect of ALSL was superior to PM (Fig. 2F, C). Taken together, ALSL and PM greatly improved HFD-induced IR in mice, and ALSL was strikingly more effective than PM. Notably, none of them affected serum HbA1c levels in a meaningful way (Fig. 2J). Furthermore, ALSL also had a marked effect on lipids (Fig. 2K–N). ALSL caused a statistically significant decline in serum LDL-C and TCHO concentrations and an elevated HDL-C concentration, while PM tended to depress LDL-C and TCHO and raise HDL-C (p = 0.064 and p = 0.167, respectively). Meanwhile, ALSL and PM were able to inhibit lipotoxicity in HFD mice by directly modifying serum levels of FFA (Fig. 2I). Overall, ALSL has some capacity to ameliorate blood lipids.

A Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IGTT) (2 g/kg body weight). B Area under the IGTT curve (AUC). C HOMA-IR was calculated using the following formula: fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) × fasting insulin (mU/L)/22.5. D Insulin tolerance test (ITT), E AUC of ITT, F HOMA-B was calculated using the following formula: (20 × fasting insulin (mU/L))/(fasting blood glucose (mmol/L)–3.5). G fasting serum glucose. H fasting serum insulin. I serum free fatty acids (FFA). J glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). K–N the content of LDL-C, TCHO, HDL-C, TC, respectively. The number of mice tested was 12 (A–F) and 8 (G–N). Data are expressed as mean ± SD, a, b, c and d means significant difference (p < 0.05).

ALSL shows improvement in serum hormones and cytokines in HFD-fed mice

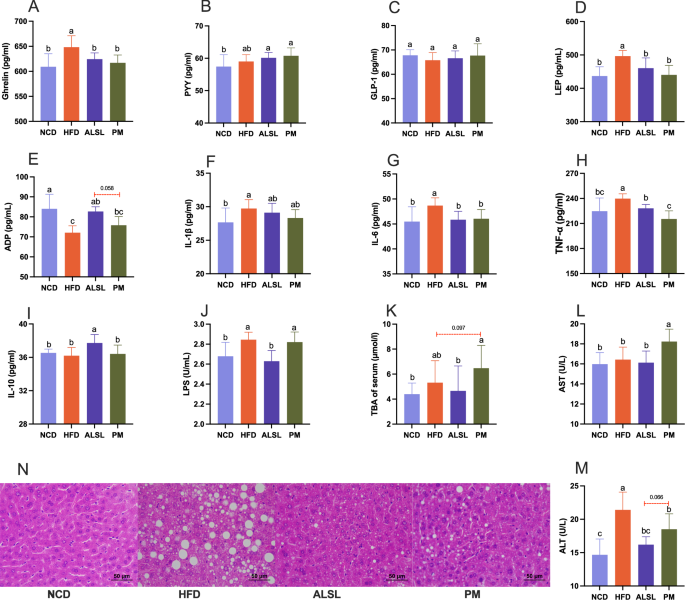

It has been verified that appetite-related hormones play an essential function in the regulation of glucose metabolism, and the increase of adipocytokines induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and participates in the development of systemic inflammation. As displayed in Fig. 3A, B, ALSL, and PM clearly attenuated the serum levels of ghrelin and tended to slightly raise the serum levels of PYY in mice versus HFD. There was no meaningful difference between ALSL and PM on serum levels of GLP-1 in mice (Fig. 3C), but both ALSL and PM clearly down-regulated serum leptin levels in HFD mice (Fig. 3D). In addition, ALSL resulted in a major increase in serum ADP levels in high-fat mice (Fig. 3E) and was more potent than PM (P = 0.058). Meanwhile, HFD caused a pronounced increase in serum levels of the pro-inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in mice (Fig. 3F–H). However, ΑLSL and PM interventions markedly decreased serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in mice on HFD, although IL-1β was only weakly reduced. ALSL markedly enhanced the level of the beneficial inflammatory factor IL-10 in the serum of mice fed the HFD (Fig. 3I). Moreover, HFD led to a significant increase in LPS serum levels in mice, whereas ALSL treatment led to a sustained down-regulation of LPS serum levels in mice (Fig. 3J). On the other hand, HFD and PM had a tendency to upregulate serum TBA in mice compared with NCD (Fig. 3K). In this study, serum ALT and AST levels were used to assess liver damage. HFD had little effect on serum AST while it substantially increased ALT levels in mice. The addition of ALSL and PM to HFD consistently down-regulated ALT levels (Fig. 3L, M, p < 0.064 and p = 0.066, respectively), with a matching trend in the results of H&E staining of the liver (Fig. 3N). To sum up, ALSL greatly alleviated HFD-induced leptin resistance and systemic inflammation and ameliorated liver function.

Serum hormones and cytokines A ghrelin, B peptide YY (PYY), C glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), D leptin (LEP), and E adiponectin (ADP). Serum inflammation-related cytokines F interleukin-1β (IL-1β), G interleukin-6 (IL-6), H tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), I interleukin-10 (IL-10), and J serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Liver function-related K serum total bile acids (TBA), L glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (AST). M glutamic pyruvic transaminase (ALT) and N H&E staining of liver. n = 6–7 Data are expressed as mean ± SD, a, b, c and d means significant difference (p < 0.05).

ALSL and PM ameliorate HFD-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis

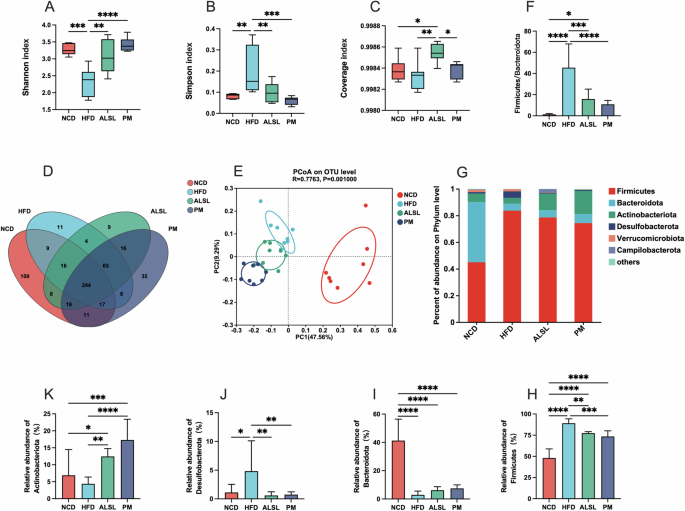

The gut microbiota is the key factor in regulating HFD-related diseases. Relative to the HFD group, the ALSL and PM groups exhibited a statistically significant gain in Shannon’s index (Fig. 4A) and a meaningful drop in Simpson’s index (Fig. 4B). The coverage index of the ALSL group was considerably higher than that of the NCD, HDF and PM groups (Fig. 4C). These revealed that ALSL and PM treatment greatly augmented α-diversity in HFD mice, and there was a clear gap between ALSL and PM. The principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) maps were used to assess the β-diversity of the samples. As depicted in Fig. 4E, mice fed the HFD had a unique microbial composition that aggregated separately from the NCD group. Mice supplemented with ALSL and PM each formed a distinct cluster with respect to the HFD group. These results implied that ALSL and PM alter the gut bacterial community in a characteristic direction. In addition, the Venn diagram in Fig. 4D demonstrated that the four groups shared 244 OTUs. Furthermore, 109 OTUs were unique to the NCD group, 11 OTUs to the HFD group, 9 OTUs to the ALSL group, and 35 OTUs to the PM group.

Microbiological analyses were conducted using 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing (n = 8 per group). α-diversity: A shannon index, B simpson index C coverage index. D Venn diagrams based on the OTU level, E β-diversity: principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the OTU level; F Firmicutes/ Bacteroidota ratio, Relative abundance of gut microbiota distribution at the phylum-level G, including Firmicutes H, Bacteroidota I, Desulfobacterota J, and Actinobacteriota K. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

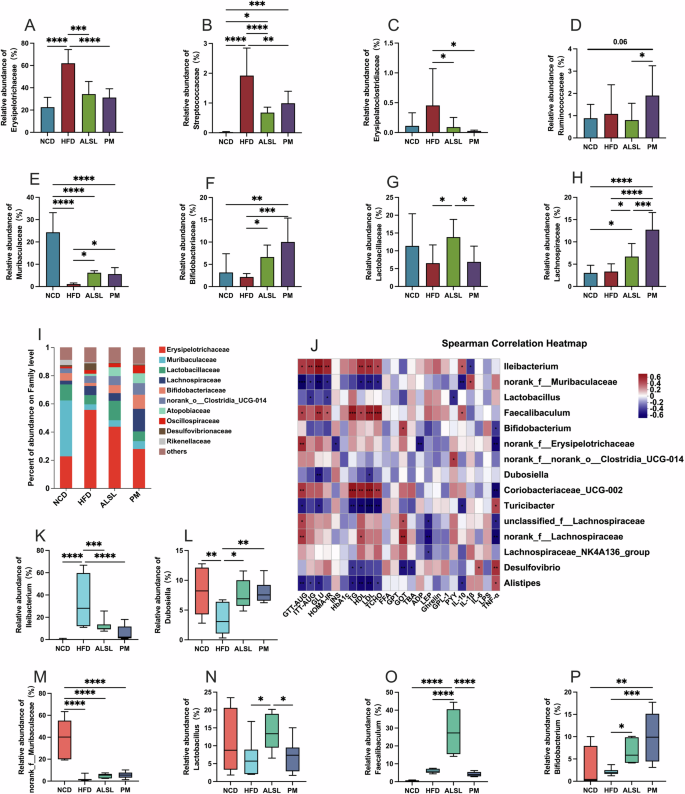

The phylum-level analysis (Fig. 4G) confirmed that the gut microbiota was dominated by six major phylums: Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota, Desulfobacterota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Campilobacterota. As opposed to NCD, HFD was associated with a pronounced upregulation of the abundance of Firmicutes (Fig. 4H), Desulfobacterota (Fig. 4K)) and the ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidota (Fig. 4F), and a down-regulated the abundance of Bacteroidota (Fig. 4I), Actinobacteriota (Fig. 4K). The supplementation of ALSL and PM clearly mitigated the HFD-induced modifications of the gut microbiota phylum levels, markedly lowering the abundance of Firmicutes (Fig. 4H), Desulfobacterota (Fig. 4J), and the ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidota (Fig. 4F), while strikingly enhancing the ratio of abundance of Actinobacteriota (Fig. 4K). At the family level, the HFD also altered the distribution of family levels in mice (Fig. 5I). In contrast to HFD, the addition of ALSL and PM to the HFD substantially diminished the abundance of Erysipelotrichaceae (Fig. 5A), Streptococcaceae (Fig. 5B), Erysipelatoclostridiaceae (Fig. 5C), and notable gains in Muribaculaceae (Fig. 5E), Bifidobacteriaceae (Fig. 5F), and Lachnospiraceae (Fig. 5H). In addition, there were also distinct differences in community proportions among ALSL and PM, with considerably more Ruminococcaceae in the PM group (Fig. 5D) than in the ALSL and NCD groups (p = 0.06), with a tendency to be higher than that of the HFD group (p = 0.14). The abundance of Lachnospiraceae was also found to be remarkably higher in the PM group than in the ALSL group (Fig. 5H), whereas, for Lactobacillaceae (Fig. 5G), the ALSL group was strikingly higher than the HFD and PM groups. These results suggest that Bifidobacteriaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Lactobacillaceae may be the main characteristic gut microorganisms that differ in gut microbiota function between PM and ALSL.

Relative abundance of gut microbiota at family level A Erysipelotrichaceae, B Streptococcaceae, C Erysipelatoclostridiaceae, D Ruminococcaceae, E Muribaculaceae, F Bifidobacteriaceae, G Lactobacillaceae, H Lachnospiraceae. I Relative abundance of gut microbiota as a percentage at the family level; J Spearman’s heatmap of correlations between the top 15 gut bacteria at the genus level and host metabolism with health parameters. Relative abundance at the genus level K Ileibacterium, L Dubosiella, M norank_f_Muribaculaceae, N Lactobacillus, O Faecalibaculum, and P Bifidobacterium; Data are expressed as mean ± SD and compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Spearman correlation analyses were employed to further explore the relationship between gut microbiota and parameters such as IR, glycolipid homeostasis, inflammation, and liver function, as seen in Fig. 5J. The abundance of Dubosiella showed a strong negative correlation with serum GLU and LDL-C levels, indicating an association with improved glucose-lipid metabolism. Furthermore, the abundances of norank_f __Muribaculaceae, Turicibacter, and Alistipes were also negatively related to parameters that represent disorders of glucose and lipid metabolism, but with some detrimental effects on inflammation. On the opposite, the high abundance of Ileibacterium, Faecalibaculum, Coriobacteriaceae UCG-002, and norank_f __Lachnospiraceae were positively correlated with parameters representing disorders of glucose and lipid metabolism and inflammation, yet Ileibacterium and Faecalibaculum had some beneficial role in influencing inflammation. As shown in Fig. 5K–P, the dominant community in the HFD group was Ileibacterium, but ALSL and PM interventions significantly reduced its abundance. The dominant bacteria in the PM group were Dubosiella and Bifidobacterium, and the prominent bacteria in the ALSL were Lactobacillus, Dubosiella, and Faecalibaculum. Among them, Lactobacillus was significantly elevated in the ALSL-treated group compared to the HFD group, showing a significant negative correlation with ITT-AUC and HOMA-IR and serum PYY levels (Fig. 5J. N), suggesting a positive correlation with improved glucose homeostasis in favor of glucose metabolism disorders and IR improvement. Meanwhile, the abundance of Dubosiella was also notably elevated by ALSL and PM supplementation (Fig. 5L). It is interesting to note that Faecalibaculum is dominant for supplementation with ALSL (Fig. 5O). However, correlation analysis showed that it has a positive correlation with the parameters of glucose and lipid metabolism disorders. In summary, the effects of ALSL and PM on improving HFD-induced IR, glucose-lipid metabolism, inflammation, and liver function may be related to changes in the gut microbiota, but may also be concurrently related to modifications in its metabolites.

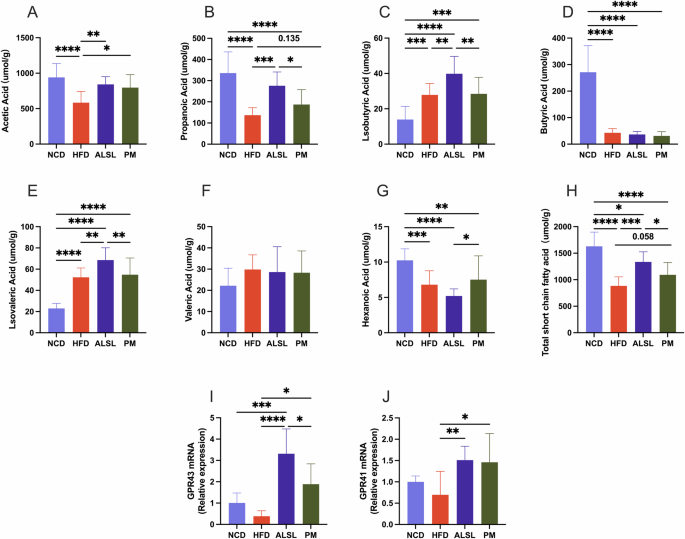

ALSL and PM improve HFD induction to varying degrees based on SCFA

SCFAs play a direct and indirect role in the interactions between the gut microbiota and the host. To investigate the relationship between gut microbiota and ALSL’s effects on IR, glycolipid homeostasis, inflammation, and hepatic impairment. The content of SCFAs in mice feces and the relative expression of hepatic SCFA receptors were detected, and the results are displayed in Fig. 6. The HFD was found to extremely significantly down-regulate the levels of acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, valeric acid, hexanoic acid, and total SCFA (Fig. 6A, B, D, G, H), and upregulate the levels of isobutyric and isovaleric acids (Fig. 6C, E), but had no marked differential effect on the levels of valeric acid (Fig. 6F). Compared to HFD, the effect of the addition of ALSL intervention was too highly significantly upregulate the content of acetic acid, propionic acid and total SCFA (Fig. 6A, B, H). Similarly, the addition of PM intervention significantly upregulated the content of acetic acid and upregulated the trend of propionic acid and total SCFA content in beneficial SCFA versus HFD. Furthermore, the ALSL group had significantly higher levels of propionic acid and total SCFA than the PM group. As seen in Fig. 6I, J, the HFD reduced the expression of GPR41 and GPR43, whereas supplementation of the HFD with PM greatly upregulated their expression, however, supplementation of the HFD with ALSL increased their expression extremely significantly, and the expression of GPR43 was markedly higher in the ALSL group than in the PM. It may also be that ALSL improves HFD-induced IR, insulin sensitivity, glucose homeostasis, fat accumulation, etc., more than PM. These observations suggested that ALSL may increase the level of SCFAs by regulating gut microbiota, thereby activating GPR41 and GPR43 and ultimately improving metabolic syndrome induced by the HFD.

SCFAs in mice feces were determined by gas chromatography (n = 8 per group). A Acetic acid. B Propionic acid. C Isobutyric acid. D Butyric acid. E Isovaleric acid. F Valeric acid. G Hexanoic acid, H Total short-chain fatty acid content. Relative mRNA transcript levels (n = 6 per group) I GPR43, J GPR41. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) after Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Structured lipids are modified lipids to improve the nutritional and functional properties of conventional plant and animal fats. In animal and human studies, MLCT has been shown to prevent IR, inflammation, and glycolipid homeostasis on HFDs14,18. In the present study, we first discussed the effects of ALSL and PM on gut microbiota composition and metabolite SCFAs, diet-induced obesity, IR, inflammation, and related metabolic disorders in HFD-fed mice. Compared to PM, our results showed that ALSL exhibited more effective modulation of HFD-induced obesity and fat deposits, IR, liver, glycolipid homeostasis disorders, and systemic inflammation. Both ALSL and PM significantly altered the gut microbiota of HFD-fed mice. In particular, SCFAs were partly responsible for the health benefits of ALSL in HFD-fed mice.

Although it is well documented that consumption of MLCT improves body fat accumulation24,25, glycolipid metabolism, and reduces inflammation26 in HFD-induced obese rats, it may also alleviate IR in HFD rats27. However, few studies have explored the metabolic and health effects of ALSL MLCT and its physical blend as an additive dose (not as a whole-fat replacement). In the present study, obesity and hepatic steatosis induced by an HFD were remarkably ameliorated by the addition of 1500 mg/kg of ALSL. Previous research has demonstrated that structural lipid modification of an HFD (long-chain triglycerides) induces obesity and fat deposition, related to the presence of MCFA and possibly to structural differences in triglycerides (by comparing the ALSL group with the PM group). Similarly, Lee et al.28 used palm oil and palm kernel oil enzymatic transesterification to synthesize MLCT (P-MLCT) oils and their physical mixtures (PKO-PO) to replace dietary fats in diet-induced obese C57BL/6 J mice. They reported that structural differences in triacylglycerols (by comparing the P-MLCT with the PKO-PO mixtures) may contribute to the body weight and body fat reduction effects of P-MLCT. The key difference was that our dose of dietary fat replacement was only 7.27‰, but it was also highly effective. The superiority of ALSL over PM in resisting HFD obesity and hepatic fat deposition may be attributed to the structural differences in TAG, with PM containing more LCT compared to ALSL. Unlike LCT, triacylglycerols of the MLCT structure, particularly the MLM type, are hydrolyzed by pancreatic lipase to produce MCFA, whereas the hydrolysis of LCT produces LCFA. While MCFA is preferentially sent to the liver for β-oxidation, LCFA is used to resynthesise new triacylglycerol molecules, which in turn increases the celiac microcirculation and ultimately contributes to the accumulation of fat. In our study, we also discovered that the accumulation of inguinal, epididymal, and perirenal fat, the deposition of fat in the liver, and the total weight gain in the ALSL group of mice were considerably lower than those in the PM group. Wang et al.18 also observed that the degree of catabolism, FFA release, and bioaccessibility of LCFA in MLCT was appreciably higher than PM through in vitro simulated digestion. The TAG structure produces different and homogeneous digestive and metabolic behaviors. This may be the main reason for the different levels of appetite-related hormones and the significantly lower energy intake in ALSL. Consequently, the presence of MCFA and TAG structures is linked to the role of ALSL in combating obesity.

HOMA-IR is a method of quantifying IR. Higher HOMA-IR values indicate that individuals are prone to diabetes. Here, we found that both 1500 mg/kg supplement (equivalent to 300 mg/kg supplement monoglyceride laurate, GML) ALSL and PM significantly improved IR and β-cell function in HFD-fed mice. The PM intervention significantly improved insulin tolerance (ITT) induced by an HFD and increased insulin sensitivity, but did not improve glucose intolerance. Importantly, the ALSL intervention significantly reversed HFD-induced glucose intolerance and ITT. This finding is consistent with the group’s previous study, where supplementation with 150, 300, and 450 mg/kg GML treatment did not improve HFD-induced glucose intolerance, and there was no significant change in the AUC of the OGTT22, but supplementation with a high dose of 1600 mg/kg GML significantly improved glucose homeostasis2. Many studies have also shown that MCLT has a beneficial effect on IR and glucose intolerance in rodents29, which correlates with MCFA content25,30. This may be related to the presence of MCFAs in MLCTs, which can regulate appetite by increasing energy metabolism and enhancing hepatic beta-oxidation of fatty acids18. On the other hand, it could be due to the enrichment of ALA in our ALSL. Studies have shown that ALA improves GTT in mice fed an HFD19,20,31. ALSL and PM showed similar effects on the regulation of hyperlipidemia, with significant decreases in serum LDL-C and FFA levels. ALSL also significantly increased serum HDL-C concentrations and PM also had a tendency to increase serum HDL-C concentrations, which was attributed to the fact that they contain similar fatty acid ratios, suggesting that the structure of TAG may have little effect on lipids. Adipocytokines are widely accepted for their ability to modulate energy metabolism and insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. Among these, leptin (LEP) enables effective regulation of common obesity-related metabolic disorders mainly through energy homeostasis and appetite suppression and may be used to predict type 2 diabetes32, and hyperleptinemia leads to the development of IR at least at the hepatic level33. ADP is expected to be a novel therapeutic tool for diabetes and metabolic syndrome due to its anti-diabetic and anti-atherosclerotic effects34. Here, not only ALSL but also PM induced a profound improvement in LEP resistance in mice fed an HFD. Compared to HFD, ALSL produced a more prominent upregulation of ADP levels and was notably higher than PM (P = 0.056). This suggested that dietary intake of ALSL ameliorates HFD-induced IR, at least in part, through a decrease in the appetite hormone LEP and an increase in ADP concentrations. Moreover, the superior effect of ALSL was manifested as the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and MCP-1) and the increase of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10). Furthermore, ALSL also reduced serum LPS concentrations, suggesting an amelioration of metabolic endotoxemia in HFD-fed mice. In conclusion, although there were differences between ALSL and PM, both ALSL and PM alleviated HFD-induced systemic inflammation. In addition, we found that the long-term addition of ALSL and PM was therapeutic for HFD-induced liver injury in rats, especially in reducing ALT, and ALSL was significantly more effective than PM. Our results are in agreement with Liu et al.35, who reported that medium- and long-chain structured lipids-based were more effective in reducing ALT compared to PM, attributed to the fact that medium- and long-chain structured lipids can maximize the use of fatty acids for liver regeneration, where MCFA at the sn-1,3 position can be directly metabolized to provide energy, and the sn-2 position of LCFA can be efficiently transported for cell membrane repair. Jiang et al.36 also suggested that ameliorating liver injury could help to alleviate IR.

The critical role of the gut microbiota and its metabolism in the pathogenesis of diet-induced obesity and related metabolic disorders has been acknowledged37,38. However, the role of gut microbes and their metabolites in ALSL’s effects in ameliorating HFD-induced IR remained to be elucidated. This study investigated the effects of ALSL and PM on gut microbes and their metabolites. The HFD resulted in a clear increase in Ileibacterium and a noticeable decrease in Dubosiella and Lactobacillus. Supplementation with ALSL reversed this change. It markedly upregulated the levels of Faecalibaculum and Bifidobacterium. PM supplementation also strongly reversed the changes in Ileibacterium and Dubosiella caused by the HFD and also significantly upregulated the levels of Bifidobacterium. According to previous reports Dubosiella39, Lactobacillus40, and Bifidobacterium8 were significantly negatively correlated with IR, which was also consistent with the correlation analysis in our study. All these microorganisms are SCFA-producing microbiota, Dubosiella was proven to alleviate the lipid metabolism disturbance and IR39, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are recognized as intestinal probiotics, and that have beneficial effects on IR and inflammation in diet-induced obese mice40. Besides, Faecalibaculum, a beneficial bacterium that produces SCFAs and belongs to the anti-inflammatory species, is significantly higher in ALSL and reduced in patients with T2DM41. In the present study, ALSL and PM interventions were found to greatly upregulate total SCFA, acetic acid, and propionic acid levels in the feces of mice fed an HFD. Propionic acid and total acid levels were much higher in ALSL than in PM, which may be related to the different effects of ALSL and PM on the gut microbiota (Fig. 5). An increase in SCFAs has been shown to be associated with lower fasting insulin concentrations, which is beneficial for insulin sensitivity42. SCFAs stimulate the growth and proliferation of pancreatic β-cells and modulate the body’s insulin sensitivity39,43. SCFAs activate endogenous G protein-coupled receptors (GPR) 41 and 43, which improve glucose homeostasis and inflammation. GPR43 has been identified as a sensor of excess dietary energy, thereby controlling the body’s energy use while maintaining metabolic homeostasis, improving insulin sensitivity, and ameliorating IR6. GPR41 regulates the sympathetic nervous system by activating it at the ganglionic level to regulate the body’s energy expenditure44. This study also found that ALSL and PM markedly upregulated the expression of GPR41 and GPR43 genes, and the expression of GPR43 was more prominent in ALSL than in PM, which may be related to the significantly higher levels of propionic acid in the ALSL group than in PM. This positive change may exert anti-inflammatory and eliminate IR effects through the SCFAs-GPR pathway6.

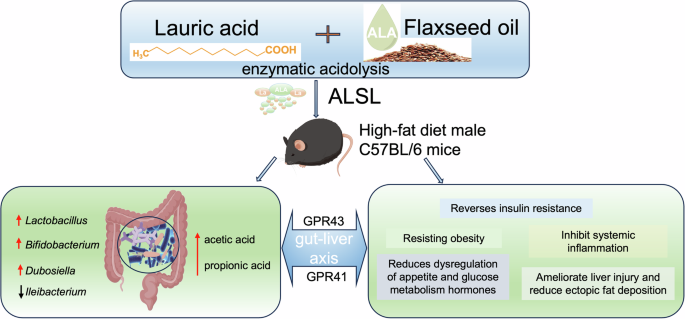

In summary, ALSL was innovatively synthesized by acidolysis enzymes and its effects on IR and gut microbes in mice fed the HFD were assessed, and potential mechanisms of action were revealed (Fig. 7). The study found that ALSL significantly ameliorated obesity, glycolipid homeostasis, inflammation, and IR induced by the HFD, and this effect may be related to its modulation of the gut microbiota and its metabolites. Specifically, ALSL upregulated Dubosiella, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium and effectively reduced the abundance of Ileibacterium, which were found to play a role in glycolipid homeostasis, inflammation, and IR by correlation analysis. Additionally, the regulatory effect of ALSL on SFCA may ultimately release health benefits, particularly by increasing propionic acid levels and enhancing the significant expression of GPR41 and GPR43 in the liver. This research was expected to open up new perspectives for the profound application of structured lipids rich in lauric and ALAs, but the positive health effects of ALSL need validation through further rigorous trials before broader implementation.

ALSL was innovatively synthesized from lauric acid and linseed oil using an acidolysis enzymes method and fed (1500 mg/kg) to high-fat diet (HFD) C57BL/6 mice. ALSL significantly ameliorated HFD-induced obesity, glucose-lipid homeostasis, systemic inflammation, and IR, and it also significantly upregulated the abundance of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Dubosiella, and downregulated Ileibacterium. In addition, ALSL upregulated acetic acid and propionic acid levels and activated hepatic receptors for short-chain fatty acids (GPR43, GPR41), thus exerting an ameliorative regulatory effect.

Materials and methods

Preparation of material

The specific method of synthesis and fatty acid composition of ALSL was done by using the method of Ying, et al.16. Physical mixtures (PM) are simple physical mixtures of FO and lauric triglycerides with fatty acid ratios similar to ALSL. Their fatty acid ratios and composition were maintained as described by Ying et al.16.

Animals and experimental design

Healthy male C57BL/6 wild-type mice (4–5 weeks old, n = 48) were acquired from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animals Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All mice were maintained at the Center for Laboratory Animal Research of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (Hangzhou, China) under standard environmental conditions (24 ± 2 °C temperature, 50 ± 5% humidity) with a 12-hour light-dark cycle and unrestricted access to food and water. After one week of acclimating, mice were randomly divided into four groups (12 mice per group, 4 mice per cage) as follows: normal control diet group (NCD), HFD group (HFD, 45% fat energy supply), ALSL group (1500 mg ALSL structural lipids to replace part of the lard in 1 kg high-fat feed), and PM group (Replace some of the lard in 1 kg of high-fat feed with 1500 mg PM, a blend of lauric acid triglycerides and FO); details of the diets were shown in Table S1. Food was supplemented weekly, and during this time the body weights and food intake of the mice were recorded. At the 16th week, all mice were placed in individual clean cages to obtain feces, immediately after defecation the feces were placed in sterile tubes and stored at −80 °C until analysis. After the 16th week, the mice were fasted for 12 h and then euthanized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg kg−1, i.v.). Tissues from the liver, spleen, kidney, epididymis, brown adipose tissue, and subcutaneous inguinal adipose tissue were collected and weighed. A piece of tissue from the liver and epididymal adipose tissue was fixed in 10% formalin, while the rest of the tissue was obtained and stored at −80 °C. All the experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Ethics Approval No.: IACUC-20211129-10) and were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Glucose homeostasis

With slight modifications according to the method of Zhong et al.45, in the 14th week, mice were fasted for 12 h, and GTT was tested by intraperitoneal injection of glucose (2 g per kg body weight). In the 15th week, mice were fasted for 6 h, and ITT was tested by intraperitoneal injection of insulin (0.5 U per kg body weight). Tail blood samples were taken at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after the injection, and blood glucose was measured using an Accu-Check glucometer (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Fasting serum insulin levels were measured using an ELISA kit (Jiyinmei, Wuhan, China), and fasting serum glucose levels were measured using a glucose oxidase assay kit (Jiangcheng Biological Engineering, Nanjing, China). The homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and the homeostatic model assessment of the β-cell function index (HOMA-Β) were calculated as:

Serum and liver biochemical analyses

Referring to the corresponding instructions and using commercial kits from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China), we determined serum levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), total cholesterol (TCHO), triglycerides (TG), glucose (GLU), total bile acids (TBA), glutamic-propanoic aminotransferase (ALT), and glutamic-oxaloacetic aminotransferase (AST). ELISA commercial kits (Wuhan Genome Biotechnology Co., Wuhan, China) were used to measure the serum levels of free fatty acids (FFA), insulin (INS), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-10 (IL-10), ghrelin, leptin (LEP), adiponectin (ADP), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), PYY, and GLP-1.

Histology analysis

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining analysis was performed according to Zhao et al.45. Briefly, tissues were taken out of 10% buffered formalin and then dehydrated through a graded series of alcohol. The dehydrated tissue was then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, H&E stained, and sectioned. Analysis of the stained sections was performed using Leica Application Suite v4 (Wetzlar, Germany). ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to calculate the size and frequency of epididymal fat.

mRNA transcript levels analysis

Follow the method of Liu et al.10. mRNA transcript levels were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR. The isolation of total RNA from the liver was conducted by the Trizol method. All the qualified RNAs were reverse transcribed according to the instructions of the PrimeScript III RT SuperMix Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd, China). Then, PCR amplification was followed as described in the ChamQ SYBR Color qPCR Master Mix Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd, China) and quantified on a 384-well LightCycler 480 system (Roche, Shanghai, China). It was calculated The relative gene mRNA expression using the 2-ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences used are given in Table S2.

Gut microbiota analysis

Follow the method described by Liu et al.10. Gut microbiota were analyzed by 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing. Briefly, from the 16th week stool samples, the bacterial DNA was isolated using the QlAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The V3-V4 range was amplified by PCR using universal primers 341 F and 806 R, respectively, (5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and (5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′). PCR amplification products were purified and quantified prior to sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequences with greater than 97% similarity were clustered using UPARSE software (https://drive5.com/uparse/) to obtain operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for classification and further analysis. All data from 16S rRNA sequencing were used to evaluate the full Majorbio Cloud platform (https://cloud.majorbio.com/). Alpha diversity of gut microbiota, including Shannon’s index, Simpson’s index, coverage index, and Venn diagrams, were analyzed at OTU level to represent different groups’ microbial diversity and richness. PCoA, which represents β-diversity was performed to show the differences in the gut microbiota between the different groups. Bacterial community maps were constructed at the phylum and family level to depict the species composition and partition of microbial species, and heatmap analysis was performed at the genus level. Then, linear discriminant effect size (LEfSe) analysis was conducted to isolate bacteria that differed from groups. Heat maps were used to visualize the correlations among microbial species and metabolic indicators.

Composition and content analysis of SCFAs

According to Zhong et al.45, fecal samples were analyzed for the composition and content of SCFAs by gas chromatography (GC). From each mice, fresh fecal samples were collected, weighed, and homogenized into 250 µL of ultrapure water at room temperature for 5 min. The suspension was made pH 2–3 by 5 M HCl and incubated for 15 min with shaking at room temperature. After 20 min centrifugation at 12,000 rpm (4 °C), the 200 µL supernatant was filled into a new centrifuge tube and made up to 1 mmol/L by 2-ethylbutyric acid. After filtration, the samples were analyzed using a Shimadzu GC-2014 system (GC-2014, SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan) and an Agilent DB-FFAP capillary column (60 m × 0.53 mm × 0.50 μm, Santa Clara, California, USA). The specific setup parameters were: oven temperature was initially set at 100 °C and held for 0.5 min, at 8 °C/min increased to 180 °C and kept for 1 min, then at 20 °C/min increased to 200 °C and kept 15 min. The injection port and ionized flame detector at 200 °C and 240 °C were maintained, and the nitrogen, hydrogen, and airflow rates were 20, 30, and 300 mL/min, with an injection volume of 1 µL.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical differences were determined using a one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test, with values of P < 0.05 indicating statistically significant differences. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Responses