The influence of task and interpersonal interdependence on cooperative behavior and its neural mechanisms

Introduction

Social interaction behaviors (SIB) refer to the exchanges and interactions between individuals through various forms, primarily including cooperation and similar engagements1,2. These interactions are essential for understanding how human brains synchronize during social interactions3,4. Recent advancements in brain imaging, particularly functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) hyperscanning, have facilitated the simultaneous observation of inter-brain synchrony (IBS) during social interactions5,6. This approach provides critical insights into the neural mechanisms that underpin cooperation and other social behaviors, highlighting the significance of synchronized brain activity in social engagement7,8.

In research on the dimensional division of SIB, researchers have conceptualized a three-dimensional structural model to dissect SIB further, delineating it into goal structure (cooperation versus competition), interactive structure (synchronous versus turn-based), and task structure (interdependent versus independent)9. This framework has propelled extensive exploration into SIB, especially through the goal and interactive structures, employing fNIRS hyperscanning. On the level of goal structure, researchers found that cooperative tasks, regardless of their synchrony, demonstrate enhanced behavioral performance and IBS in contrast to competitive tasks10,11. Additionally, research findings indicated that cooperation tasks, synchronous interactive structure, exemplified by cooperation key-pressing tasks, yield superior behavioral outcomes and heightened IBS compared to their turn-based counterparts, such as cooperation tangram puzzle tasks12. In the task structure dimension, previous research has found that cooperative tasks emphasizing interdependence exhibit higher behavioral performance and IBS compared to competitive tasks that emphasize independence. However, there remains greater complexity within interdependent tasks themselves. In particular, the differential impact of varying levels of interdependence on behavioral performance and neural mechanisms has not yet been fully elucidated. Thus, our study focuses on the sub-dimensions of the three-dimensional structural model, namely goal structure (cooperation), interactive structure (synchronous), and task structure (interdependent), aiming to investigate how cooperation key-pressing tasks with different levels of interdependence affect cooperative behavior and IBS.

Previous studies have elucidated the impact of task interdependence on cooperation from theoretical and behavioral perspectives, but there is a lack of neurobiological evidence. Previously, researchers have proposed from a theoretical perspective that positive interdependence is key to achieving effective cooperation13. Subsequently, other researchers have focused on the impact of task interdependence on cooperation14,15. Behavioral experiments have demonstrated that task interdependence had an indirect impact on cooperation performance. Participants were involved in a card-sequencing activity task, where Low Interdependent Cooperation Task (LICT) required participants to only sequence their own cards, while High Interdependent Cooperation Task (HICT) required participants to collectively sequence a set of cards. The results revealed that in HICT, the higher the organizational citizenship behavior, the better the cooperation performance14. And the application of structural equation modeling revealed that task interdependence could directly and positively predict team performance15. However, previous studies did not directly investigate the causal relationship and the underlying neural mechanisms between task interdependence and cooperation. Moreover, previous hyperscanning research has shown that, compared to low-interdependence competitive key-pressing tasks, high-interdependence cooperative key-pressing tasks are more likely to enhance IBS10. Another study found that high interdependence cooperative puzzle tasks also led to greater intra-brain activation compared to low interdependence competitive puzzle tasks11. Therefore, even in cooperative tasks, the level of task interdependence may be a critical factor influencing cooperative behavior, intra-brain activation, and IBS, which requires further investigation.

In addition to the interdependence effect of cooperation situations, the Social Interdependence Theory (SIT) posited that the interdependence between individuals was a key factor that triggered the occurrence of cooperation behavior13,16,17. Social scientist Mark Granovetter categorized the strength of individual connections in a social network into two types: strong ties (i.e., friends) and weak ties (i.e., strangers)18. Previous research found that the behavioral performance and IBS during the cooperation key-pressing task were better in couple dyad compared to friend and stranger dyads19, indicating that the performance of cooperation was related to the strength of connections and the level of familiarity among individuals. Furthermore, recent research has found that in a joint Simon task, friend dyads exhibit better behavioral performance, both higher intra-brain activation and IBS than strangers20. However, interdependent interpersonal relationships possessed multiple attributes and were distinctive in terms of familiarity, attractiveness, and gender pairing. Additionally, studies indicated that in cooperative key-pressing tasks, the behavioral performance and IBS of mixed-gender pairs were superior to those of same-gender pairs21. To eliminate the potential confounding effects of gender and attractiveness on the study results, this research selected same-gender friend and stranger dyads as our research subjects.

The present study delves into the dynamics of cooperative behavior through fNIRS hyperscanning, focusing on the cooperation key-pressing task for its robust experimental control and minimal confounds, revealing enhanced behavioral performance and IBS over turn-based tasks10,19,21. To examine the impact of task and interpersonal interdependencies, we differentiate between HICT and LICT. HICT focuses on mutual adjustment and synchrony between participants to achieve a high score10, contrasting with LICT, which requires individual efforts towards a common goal, emphasizing speed. To examine interpersonal interdependence, both friend and stranger dyads are recruited, allowing an analysis of how social ties influence cooperative performance and neural coordination. Meta-analyses have identified significant intra-brain activations and IBS in areas such as the Right Prefrontal Cortex (PFC.R), the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC.L), the Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC.R), and the right Temporo-Parietal Junction (TPJ.R) associated with cooperative tasks22. And prior studies have speculated that the intra-brain activation and IBS in bilateral DLPFC during cooperation processes may be linked to individuals’ cognitive control abilities12,23. Thus, the study focuses on these regions, along with PFC.R, DLPFC.L, DLPFC.R, and TPJ.R, as core regions of interest (ROI), to analyze the neural underpinnings of cooperation under different levels of task and interpersonal interdependence.

In summary, this study utilized a three-dimensional SIB model to refine the cooperation key-pressing task into HICT and LICT, employing fNIRS hyperscanning to examine how task interdependence influences cooperative behavior and its underlying neural mechanisms. Although previous studies have explored the impact of task interdependence on cooperation, there is a lack of direct evidence regarding the underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Furthermore, while existing literature discusses the role of interpersonal interdependence in cooperation, no studies have yet compared the effects of different relationship types (such as friends versus strangers) in varying interdependent cooperative tasks. Thus, this research aims to fill these critical gaps by providing a deeper understanding of the interactive effects of task interdependence and interpersonal interdependence on cooperative behavior and neural mechanisms. In conclusion, the study proposed three hypotheses that awaited validation. First, task interdependence may impact cooperative behavioral performance and IBS. Compared to LICT, HICT might enhance behavioral performance and IBS. Second, interpersonal interdependence may influence cooperative behavioral performance and IBS. Compared to stranger dyads, friend dyads might enhance behavioral performance and IBS. Third, task interdependence and interpersonal interdependence may interactively affect cooperative behavioral performance and IBS. Task interdependence may modulate the impact of interpersonal interdependence on cooperative behavioral performance and IBS, and interpersonal interdependence may also modulate the impact of task interdependence on cooperative behavioral performance and IBS.

Results

Behavioral scores results

This study primarily assesses the behavioral performance, intra-brain functional connectivity (FC), and IBS of friend and stranger dyads during high and low interdependent cooperation tasks. Both tasks required participants to cooperate in key-pressing to score points, but with key differences: in the high interdependent cooperation task, participants were required to press the keys simultaneously, with higher scores awarded when their response times were closely matched; whereas in the low interdependent cooperation task, each participant had their own standard response time, and scores were given only if they pressed the key faster than their respective standard times.

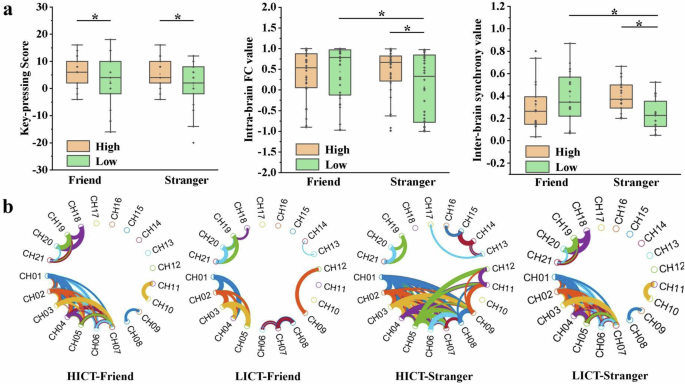

We aimed to investigate the impact of task and interpersonal interdependences on cooperative behavior performance. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a 2 (task interdependences: high interdependence and low interdependence) × 2 (interpersonal interdependences: friend and stranger dyads) design was used to analyze the key-pressing scores. The behavioral results showed a significant main effect of task interdependences, F (1, 32) = 4.864*, p = 0.035, ηp2 = 0.132. However, there was no significant main effect of interpersonal interdependences, F (1, 32) = 0.425, p = 0.519, ηp2 = 0.013, and the interaction effects between task interdependences and interpersonal interdependences were also not significant, F (1, 32) = 0.040, p = 0.842, ηp2 = 0.001. Post hoc tests revealed that the key-pressing scores under the HICT were significantly higher than those under the LICT, p = 0.035. All the reported p-values in this section and throughout the subsequent text were results after Bonferroni correction. The specific results can be seen in the first image from the left in Fig. 1a.

a The plots display the differences in behavioral scores, intra-brain FC, and IBS of friend and stranger dyads under high interdependent cooperation task (HICT) and low interdependent cooperation task (LICT), presented from left to right. b The plots display the intra-brain FC of friend and stranger dyads under HICT and LICT, presented from left to right. (Note: Error bars represent interquartile range; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p <0.001).

Intra-brain functional connectivity results

We aimed to investigate the impact of task and interpersonal interdependences on intra-brain FC across 21 channels. A repeated measures ANOVA with a 2 (task interdependences: high interdependence and low interdependence) × 2 (interpersonal interdependences: friend and stranger dyads) design was used to analyze the intra-brain FC values across 21 channels. The intra-brain FC results indicated a significant interaction effect between task interdependences and interpersonal interdependences in the BA9 (CH04: DLPFC.R) and BA40 (CH18: Right Supramarginal Gyrus, SMG.R), F (1, 66) = 4.234*, p = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.060. However, there was no significant main effect of task interdependences, F (1, 66) = 1.428, p = 0.236, ηp2 = 0.021, and the main effect of interpersonal interdependences was also not significant, F (1, 66) = 1.356, p = 0.248, ηp2 = 0.020. Post hoc tests revealed that under the LICT, the intra-brain FC values under the friend dyad were significantly higher than those under the stranger dyad in the BA9 (CH04: DLPFC.R) and BA40 (CH18: SMG.R), p = 0.041. Furthermore, under the stranger dyad, the intra-brain FC values under the HICT were significantly higher than those under the LICT in the BA9 (CH04: DLPFC.R) and BA40 (CH18: SMG.R), p = 0.026. The results of the interaction can be seen in the second image from the left in Fig. 1a, and the results of the intra-brain FC are shown in Fig. 1b.

Inter-brain synchrony results

We aimed to investigate the impact of task and interpersonal interdependences on IBS across 21 channels. A repeated measures ANOVA with a 2 (task interdependences: high interdependence and low interdependence) × 2 (interpersonal interdependences: friend and stranger dyads) design was used to analyze the IBS values across 21 channels. Within the BA40 (CH18: SMG.R), the IBS results indicated a significant interaction effect between the task and interpersonal interdependences, F (1, 32) = 8.234**, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.205. However, there was no significant main effect of the task interdependences, F(1, 32) = 0.769, p = 0.387, ηp2 = 0.023, and no significant main effect of the interpersonal interdependences, F (1, 32) = 0.664, p = 0.421, ηp2 = 0.020. Post hoc tests revealed that under the LICT, the IBS values under the friend dyad were significantly higher than those under the stranger dyad within the BA40 (CH18), p = 0.019. Furthermore, under the stranger dyad, the IBS values under the HICT were significantly higher than those under the LICT within the BA40 (CH18), p = 0.012. The results of the interaction can be seen in the third image from the left in Fig. 1a, and the results of the IBS is shown in Fig. 2a.

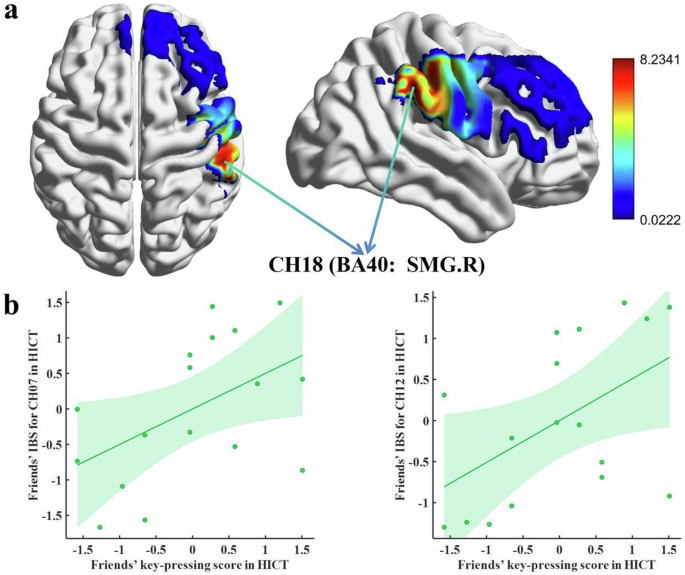

a The heat map depicts the IBS of friend and stranger dyads in all channels during the high interdependence cooperative task (HICT) and low interdependence cooperative task (LICT). Two-way ANOVA F-value brain heat maps, with task interdependence as the within-subject variable and interpersonal interdependence as the between-subject variable. The F-maps were generated using a spatial interpolation linear method. The MNI coordinates and the 21 F-values from the interaction effect across 21 channels were converted into *.img files using xjView and rendered over the 3D brain model via BrainNet Viewer54. No thresholding was applied; the F-values displayed are post-Bonferroni corrected, ranging from 0.022 to 8.234. The brain region corresponding to the most significant interaction, channel 18 (BA40: SMG.R), is highlighted in the figure. b The scatter plot above shows the correlation between friend dyads’ behavior scores in HICT and IBS in channel 7 (BA9: DLPFC.R), while the plot below presents the correlation between friend dyads’ behavior scores in HICT and IBS in channel 12 (BA45: PTR.R). All heat map was generated using BrainNet Viewer (version 1.7) 45, a MATLAB-based tool54.

Behavioral scores and inter-brain synchrony correlation results

We aimed to investigate the Pearson correlation between cooperative behavior performance and IBS across 21 channels. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the correlations between key-pressing scores and IBS values across 21 channels. The results showed a significant positive correlation were found in the HICT between friend dyad’ key-pressing score and IBS in BA9 (CH07: DLPFC.R) (r = 0.500*, p = 0.041), and in the HICT between friend dyad’ key-pressing score and IBS in BA45 (CH12: Right Pars Triangularis, PTR.R) (r = 0.510*, p = 0.036). The specific correlation results can be found in Fig. 2b.

Discussion

Although previous research has explored IBS in synchronous cooperation tasks10,19, the degrees of task and interpersonal interdependences between cooperation partners can vary considerably in real-life situations. The impact of task and interpersonal interdependence on synchronous cooperation tasks remains to be further studied. Thus, this study employed fNIRS hyperscanning technique, using a classic adapted cooperation key-pressing task, with the aim of investigating the influence of task and interpersonal interdependences on cooperation efficiency and neural mechanism. In this context, cooperation was defined as participants sharing a common goal and working together to achieve high scores in the tasks. Our research findings indicated that the HICT could improve cooperative behavioral performance in friend and stranger dyads, strengthen the intra-brain FC between DLPFC.R and SMG.R in stranger dyads, and elevate IBS in SMG.R in stranger dyads. Moreover, the interdependence of cooperation partners was found to strengthen the intra-brain FC between DLPFC.R and SMG.R in the LICT, and elevate IBS in SMG.R in the LICT.

The behavioral results revealed that both friend and stranger dyads, scores in HICT were significantly higher compared to LICT. These findings were consistent with research hypothesis 1. The behavioral findings provided support for the SIT, which posited that different situational characteristics lead to different outcomes. In situations of high interdependence, individual or group success and achievement were contingent upon cooperation with each other13,16,17. This study further discovered that task interdependence could facilitate cooperation among individuals. Although the goals set in all two tasks were to cooperate and achieve the highest possible scores together, under condition of HICT, cooperators not only needed to react quickly but also had to consider their partner’s response time to match as closely as possible. In LICT, cooperators only needed to respond as quickly as possible based on shared or individual goal stimuli. The results indicated that the cooperative scores in the HICT were higher compared to the LICT. The higher the level of task interdependence between the cooperating individuals, the better their cooperative performance. The Social Identity Theory proposed that when members of a group were in a task structure of high interdependence, psychological distance was reduced, leading to natural cooperation24. In this study, the HICT required participants to keep their key-pressing times as close as possible, potentially reducing the psychological distance between individuals, and the moderating effect of task interdependence reduced the interpersonal distance difference between friend and stranger dyads. The current results indicated that, regardless of whether the participants were friend or stranger dyads, the high interdependent tasks yielded high cooperative scores, and the interdependence between cooperators did not interact with cooperation interdependence. We speculated that this may be related to the nature of the cooperative task. The cooperative key-pressing task used in this study primarily focused on physical synchronization, whereas differences between friend and stranger dyads might emerge in tasks that require tacit coordination or verbal communication9,23.

Recent studies found intra-brain FC between the bilateral DLPFC brain regions during the cooperation key-pressing task, as well as IBS in the SMG.R brain region during the cooperation tangram puzzle task23,25. And this study further unveiled the interaction effects of the task and interpersonal interdependences on the intra-brain FC in the DLPFC.R and SMG.R brain regions. This finding aligned with research hypothesis 3. First, we found that the impact of task interdependence on intra-brain FC depends on the level of interpersonal interdependence. Specifically, heightened task interdependence is associated with increased intra-brain FC between the DLPFC.R and SMG.R brain regions among strangers, but not among friends. Previous studies have suggested that the cooperative key-pressing task may be associated with the activation of brain regions related to cognitive control, particularly the DLPFC12, which has also been identified as a core brain region involved in cognitive control within social contexts26,27. In the HLCT employed in this study, cooperation between participants requires continuous coordination to achieve a shared goal10,19. Participants adjust their actions based on their partner’s keypress feedback, necessitating the inhibition of dominant responses and the alignment of their behavior with that of their partner12. This coordination process may enhance IBS in the DLPFC.R, a brain region associated with cognitive control. In the HLCT, successful cooperation is defined by the convergence of response times between the two participants, a process that requires a high degree of coordination and synchronization10,19. This coordination involves not only adjusting one’s behavior in response to the partner’s actions but also understanding and predicting the partner’s intentions and movements12,23. The mirror neuron system (MNS) plays a critical role in enabling individuals to comprehend the intentions behind others’ actions and enhances their ability to mimic and synchronize behavior28. Consequently, in the HLCT, a task that necessitates such high levels of coordination, the process may engage IBS in the SMG.R, a brain region closely associated with the MNS. Furthermore, friends typically share higher levels of tacit understanding and mutual comprehension, enabling effective coordination regardless of the level of task interdependence20,23,29. In contrast, strangers lack this tacit understanding and may require greater reliance on cognitive control mediated by the DLPFC.R, as well as MNS-related activation in the SMG.R, particularly in tasks requiring high levels of coordination such as the HLCT.

Secondly, we found that the impact of interpersonal interdependence on intra-brain FC depends on the level of task interdependence. Specifically, in LICT, friends showed greater intra-brain FC between the DLPFC.R and SMG.R brain regions compared to strangers. However, in HICT, there was no significant difference between the two groups, which is consistent with previous research findings19. HICT places a high demand on bodily synchronization, exceeding the realm of individual tacit understanding, and becomes a challenge requiring extremely high bodily synchronization9. Friends and strangers, under this high interdependence condition, may face the same difficulties and challenges, resulting in no significant differences in intra-brain FC between the two groups. Recent research has found that in cooperative Simon tasks, friend dyads exhibit significantly stronger intra-brain activation among the bilateral DLPFC brain regions compared to stranger dyads20. Another study found that in interdependent cooperation puzzle tasks, both friend and stranger dyads exhibited the most pronounced intra-brain FC during the DLPFC.R and SMG.R brain regions. Another study found that in interdependent cooperation puzzle tasks, both friend and stranger dyads exhibited intra-brain FC in the DLPFC.R and SMG.R brain regions23. In this study, under the LICT, successful cooperation was defined by both parties’ response times needing to exceed their individual average speeds, aiming to achieve the goal as quickly as possible. LICT reduces the requirement for coordination between the interacting parties and emphasizes individual speed. Friends exhibit better rapport and trust, may lead to increased dedication to task completion, which mobilizes activation in goal-oriented cognitive control and MNS-related brain regions. Additionally, the relationship between friends may foster higher motivation and involvement, thereby influencing their performance in the task.

This study indicated that the effect of task interdependence on IBS is influenced by interpersonal interdependence. HICT enhanced the IBS in the SMG.R among strangers but had no effect on friends. These findings aligned with research hypothesis 3. The Interactive Prediction Theory proposed that in social interactions, each individual possessed a brain system that controlled their own behavior and predicted the behavior of their partners30,31. IBS reflected the similarity in brain activity patterns between cooperating individuals10,32, and HICT placed higher demands on mutual adaptation when both parties were engaged in the same task. However, among friends, the emphasis on bodily synchronization in HICT does not affect them due to the long-established rapport and trust. In contrast, for strangers, HICT can quickly bridge their psychological distance, enhancing the IBS in the SMG.R brain region associated with MNS and social cognition23,28. Although both HICT and LICT emphasize high scores through cooperative goals, HICT focuses on achieving high scores through mutual physical coordination, while LICT diminishes this aspect of physical coordination and emphasizes task consistency for high scores. Previous research has classified cooperative key-pressing tasks as low-level motor control cooperative tasks, while cooperative puzzle tasks are considered high-level cognitive cooperative tasks. It has been found that the synchrony in cooperative key-pressing tasks is significantly stronger than in cooperative puzzle tasks12. Additionally, it has been found that emphasizing high interdependence cooperative tasks in cooperative puzzle tasks is better for IBS than emphasizing low interdependence division of labor cooperative tasks23. Interestingly, our study found that even in low-level motor control cooperative key-pressing task, high interdependent cooperation can increase IBS related to SMG.R brain regions during cooperation with strangers, further demonstrating the involvement of SMG.R in MNS in social contexts. Previous studies used the cooperative key-pressing paradigm and cooperative tangram puzzle to assess the differences in IBS among romantic partners, friends, and strangers during cooperative tasks. The results showed no significant difference in IBS between friend and stranger dyads19,33. Based on SIT and task structure of social interactive behaviors9,13,16,17, we hypothesized that this might be related to task interdependence. Our study results, however, demonstrated no significant IBS between friend and stranger dyads in HICT, which was consistent with previous research19,33. This may be interpreted as HICT emphasizing more on the consistency of physical coordination, with a greater focus on assessing the mutual coordination abilities between friends and strangers, while the synchrony among friends is more reflected in psychological synchrony9,23. However, we found that in LICT, the IBS in the SMG.R brain region was significantly stronger in friend dyads compared to stranger dyads, confirming our hypothesis 3. In LICT, the consistency of physical coordination between interacting parties wasn’t emphasized, but participants with the same tasks completed them faster than the computer’s standard time. Mutual understanding among friends could enhance IBS in LICT with shared task goals, potentially triggering activation in the SMG.R brain region associated with MNS.

In HICT, we observed a significant positive correlation between the key-pressing scores of friend dyads and IBS in the DLPFC.R and PTR.R brain regions. HICT imposes higher demands for mutual key-pressing coordination among friend dyads, which may promote activation of the DLPFC.R associated with the cognitive control, and PTR.R region associated with the MNS, enhancing its IBS23,34. This suggests that during HICT, the behavioral performance of friend dyads may benefit from enhanced coordination facilitated by the MNS. Overall, the findings indicate distinct patterns in the relationship between behavioral performance and IBS among and friend dyads in HICT. These patterns underscore the roles of cognitive control and MNS in facilitating cooperation among friends and the cognitive control processes in enhancing cooperative performance in both cooperative task environments.

The findings of this study have significant implications for both work and educational environments. Increasing cooperation interdependence can not only enhance work efficiency but also foster cooperation and team collaboration in educational settings. Specifically, in work environments requiring teamwork, cooperation interdependence enhances coordination and efficiency among team members, especially in high interdependent cooperation, where cooperation becomes more natural, communication costs are reduced, and overall goals are achieved more effectively. In education, teachers can promote better collaboration and mutual understanding among students by designing tasks with high interdependence, ultimately improving learning outcomes and fostering team spirit.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the fNIRS device’s limited channel capacity confined our study to the PFC and the TPJ.R. Nonetheless, within these targeted areas, we observed significant variations in intra-brain FC and IBS associated with these ROIs. Future research could focus on other brain regions that were not covered in this study. Secondly, this study focused on the behavioral and IBS differences in synchronous cooperation under varying levels of task interdependence. Future studies could expand on this by comparing synchronous and turn-based cooperation tasks under different task interdependence conditions, revealing the neural mechanisms across different cooperative modes. Thirdly, while the main focus of this study was on task and interpersonal interdependence, future research could explore how gender influences verbal communication tasks under different levels of task interdependence, providing further insights into the role of gender in cooperative dynamics. Fourth, this study focused on a cooperative key-pressing task that emphasized bodily synchronization, whereas real-world cooperative situations are often more complex. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. Lastly, individual differences (e.g., cooperative tendencies) were not considered in this study, and future research could incorporate these factors to gain a more comprehensive understanding of their potential influence on cooperative behavior.

Methods

Participants

The required sample size for this study was determined using G*Power 3.1.9.4 statistical analysis software34. According to the experimental design of this study, at least 27 pairs of participants were required to achieve a medium effect size, where Cohen’s f = 0.25, with a Type I error probability of 0.05 (α = 0.05), and a Type II error probability of 0.20 (1 − β = 0.80)35. A total of 72 participants were recruited for the study, including 70 right-handed and 2 left-handed individuals. Given the potential influence of handedness on the experimental outcomes, the two left-handed participants, who were allocated to different groups, were excluded from the analysis. Consequently, data from 68 right-handed participants were included in the final statistical analysis. Therefore, a total of 68 college students (age: 19–29 years, M = 21.840 years, SD = 1.626) were recruited for this experiment, including 38 males and 30 females, forming 34 same-gender pairs of participants. They all participated in two key-pressing tasks, presented in a balanced order. Before the experiment, participants completed the Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale36, and those with familiarity ratings above 4 points were included in the friend group33,37. 17 pairs of participants who knew each other formed the friend group, while 17 pairs of participants who were unfamiliar with each other formed the stranger group. In the friend group, there were 9 male-male pairs (M = 21.778 years, SD = 1.629) and 8 female-female pairs (M = 21.562 years, SD = 0.964). In the stranger group, there were 10 male-male pairs (M = 22.500 years, SD = 2.013) and 7 female-female pairs (M = 21.286 years, SD = 1.437). Before the experiment, all participants provided written informed consent, and they received compensation based on their performance after the experiment. This study obtained approval from the Academic Ethics Committee of Anhui Normal University (AHNU-ET2023094). The study procedure was carried out following the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were compensated with a predetermined reward upon completion of the experiment.

Tasks and procedures

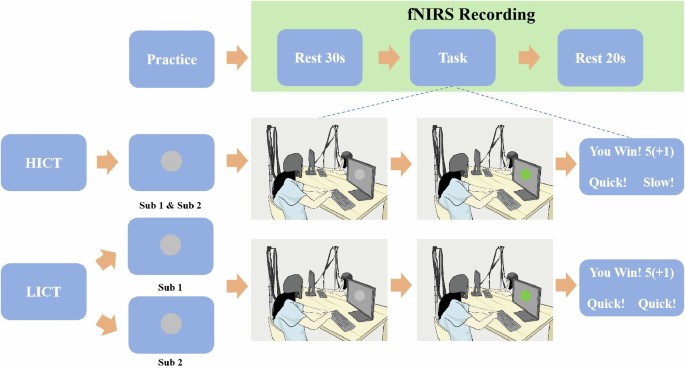

After arriving at the laboratory, the two participants were randomly assigned to sit on the left and right sides, facing each other. To prevent the participants from observing each other’s key-pressing during the task, the computer monitor was positioned at an angle. Before the experiment began, the participants were informed about the rules and procedures of the study and were emphasized that they should not engage in any verbal or non-verbal communication with each other throughout the entire formal experimental process. Before the formal start of the experiment, the participants first engaged in practice games. Once the participants confirmed their understanding of the experimental rules and procedures, the experiment officially began. Before the formal games, the participants were asked to close their eyes and rest for 30 s to reach the baseline state of blood oxygenation38. During this stage, the participants were required to keep their bodies relaxed. After the experiment started, the participants were required to complete two rounds of cooperation key-pressing tasks (with a random task order). After each round of the task, there was a 20 s rest period to ensure that the blood oxygen level returned to baseline. The experimental tasks were presented using E-prime 3.0 to display stimuli, collect participant responses, and control the experimental procedure. The monitor size was 16 × 10 cm, with a spatial resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels, and the distance to the participants was set at 60 cm.

High interdependent cooperation task: The two cooperative tasks in this study were adapted from Cui et al.10’s cooperation key-pressing paradigm (as shown in Fig. 3). The participants’ objective was to achieve a high score in the cooperation tasks. In the HICT, a hollow gray circle appeared in the center of the screen, followed by a green circle (target stimulus) filling the gray circle. When the target stimulus appeared, the two participants were required to press the keys synchronously with their dominant hands as quickly as possible. The left participant pressed the “A” key, and the right participant pressed the “1” key. At the end of each trial, feedback on the actual response time (RTleft and RTright) and the degree of similarity in response times between the two participants would be provided, indicating whether they were “fast” or “slow” in their key-pressing. When the key-pressing response times of the two participants were close, they received 1 point. The scoring criterion for cooperative key-pressing was as follows: if |RTleft − RTright | < |RTleft + RTright |/8, they could receive 1 point; otherwise, they lost 1 point. There were five practice trials, and the formal experiment only commenced once participants had fully familiarized themselves with the experimental rules. After the practice trials, we ensured that all participants were comfortable with the rules before proceeding to the formal experiment. If any participants were unsure of the rules, they were given the opportunity to repeat the practice session.

Practice → 30 s → Formal Block (comprising randomly balanced HICT and LICT. In HICT, two individuals practice together for five trials, followed by a formal experiment of 20 trials, aiming to synchronize key-pressing times for higher scores, with feedback provided each round. In LICT, each person practices independently for ten trials, then proceeds to a formal experiment of 20 trials, aiming to press keys faster than the computer for higher scores, also with feedback provided each round.

Low interdependent cooperation task: The difference between the LICT and the HICT was that, in the LICT, participants were informed in advance that the program would set a standard time based on their responses (as shown in Fig. 3). During the practice phase, each participant completed ten individual trials. This standard time was derived from the average response times (RT1 and RT2) of the last seven practice trials for each participant. In the practice phase, no key-pressing feedback reminders were given after each trial, only requiring the participants to respond as quickly as possible. The formal phase consisted of 20 trials, and after each trial, feedback indicating “Your key-pressing was fast/slow” was provided. If both participants were faster than their respective standard times, they received 1 point; otherwise, they lost 1 point. During the practice phase, both participants needed to practice individually for ten trials. The key-pressing scoring criterion was as follows: RTleft > RT1 and RTright > RT2.

fNIRS data acquisition

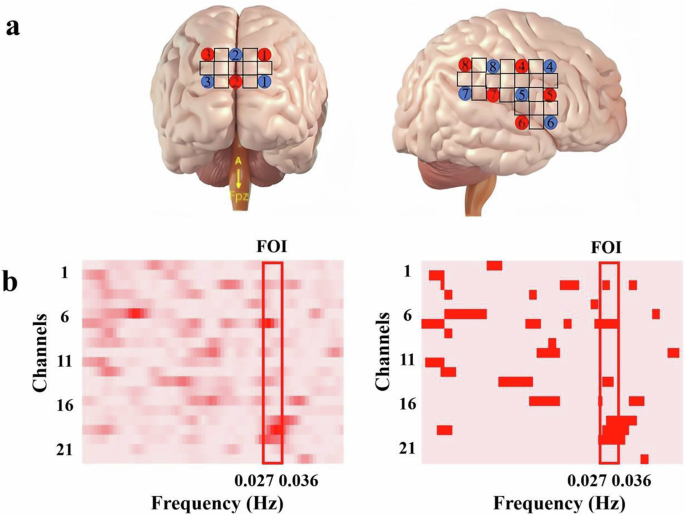

This study used two NIRSport portable fNIRS systems from NIRx Inc., USA. The equipment employed continuous-wave measurements of cortical hemodynamic activity at two wavelengths (760 nm and 850 nm). Using the modified Beer-Lambert law, allowed for the collection of changes in oxygenated hemoglobin, deoxygenated hemoglobin, and total hemoglobin. The experimental sampling rate was 7.8125 Hz, and each device consisted of eight emitters and eight receivers. The optode layout template formed a total of 21 channels, with a distance of 3 cm between each Sources/Detectors pair. Each Sources/Detectors pair was defined as a measurement site, covering the PFC.R, DLPFC.L, DLPFC.R, and TPJ.R (see Fig. 4a). Based on findings from previous research, this study identified these brain regions as ROIs10,12,22. The ROIs were determined using the fOLD toolbox (fNIRS Optodes’ Location Decider) based on MATLAB39. Subsequently, the anatomical positions of optodes and channels on the head were standardized in 3D using the NIRS_SPM toolbox based on MATLAB (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/nirs_spm/), obtaining the MNI coordinates of the optodes and the cortical localization probability of all 21 channels40,41,42 (see Table 1).

a fNIRS channels and probe placement diagrams. The left image shows a frontal view of the brain, and the right image presents the right hemisphere. Red indicates sources, blue represents detectors, and black marks channels. b Frequency band selection. The left image displays F-values from the interaction of the ANOVA on task-related and group-related Wavelet Transform Coherence (WTC). Task-related WTC refers to coherence under high and low interdependent cooperation tasks, while group-related WTC refers to coherence under friend and stranger dyads. The right image shows P-values from the same interaction. Red blocks highlight channels with p < 0.05, and the red border indicates the frequency band from 0.023 Hz to 0.032 Hz.

Data analysis

This study aims to investigate the effects of task and interpersonal interdependences on cooperative behavior, intra-brain FC, and IBS. To explore these relationships, we conducted both behavioral and neuroimaging analyses. Behavioral data were collected through key-pressing scores and analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA to examine the effects of task and interpersonal interdependences on participants’ behavioral performance. Additionally, Pearson correlation analyses were performed to explore the relationship between key-pressing scores and IBS. For neuroimaging data, intra-brain FC was assessed through preprocessed, filtered data and calculated based on Pearson correlation coefficients between channels, measuring the strength of FC between different brain regions. A repeated measures ANOVA was then used to assess how task and interpersonal interdependences influenced intra-brain FC. Finally, IBS was assessed using unfiltered preprocessed data, frequency band selection based on permutation tests, and Wavelet Transform Coherence (WTC) to calculate IBS, which evaluated the synchronization between participants’ brains during cooperative tasks. Repeated measures ANOVA was subsequently applied to examine the effects of task and interpersonal interdependence on IBS.

Behavioral data analysis: The program written in E-prime software recorded the scores of each trial and the cumulative scores for each round of the participants. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a 2 (task interdependence) × 2 (interpersonal interdependence) design was conducted on the total scores for each round of the task using SPSS 24.0 statistical software. Additionally, Pearson correlation analyses were performed to examine the relationship between key-pressing scores and IBS values.

fNIRS data analysis

Raw data preprocessing

The fNIRS raw data were preprocessed using the HOMER2 software package in MATLAB 2017b. First, in the initial step of preprocessing using HOMER2, we performed a visual inspection of the optical density trajectories to assess the quality of coupling between the photodiode and the scalp. Problematic channels were marked and excluded from further analysis. Subsequently, the “Exclude Time” button was used to manually remove segments of data with excessive noise. Second, the raw optical density data from 21 channels were converted into optical intensity signals based on the modified Beer-Lambert law. Third, since the coefficient of variation is easily influenced by extreme values caused by motion artifacts, we assessed the quality of the channel signals after artifact correction, with a threshold set at 0.25. And the hmrMotionArtifactByChannel and hmrMotionCorrectSpline functions were utilized to detect and correct artifacts (with parameters set as tMotion = 0.5, tMask = 2, STDEVthresh = 20, AMPthresh = 0.5, pSpline = 0.99)43. Finally, to eliminate the influence of environmental noise and remove physiological artifacts, a bandpass filter ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 Hz was applied (Note that the preprocessing for WTC analysis did not involve filtering, while the rest of the steps remained the same)20,23. After the data underwent preprocessing, it was transformed into hemoglobin concentration44,45,46. Since the signal of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) was more sensitive to changes in cerebral blood flow compared to deoxygenated hemoglobin signal47, this study focused on the analysis of HbO signal.

Intra-brain functional connectivity

Referring to the analysis methods used in previous studies, we imported the filtered data (filtered within the range of 0.01–0.2 Hz) after preprocessing with homer2 into MATLAB 2023b for subsequent analysis12,23. Prior to processing, we excluded identified problematic channels based on homer2 preprocessing outcomes, ensuring their exclusion from subsequent data analyses41,42. Following this, the data was segmented into two states preceding the task initiation, with the baseline capturing HbO data ~30 s before the task onset12,33. In this study, we employed the Pearson correlation coefficient as a quantitative measure of FC strength12,33. The “corr.m” function in MATLAB was utilized for calculating intra-brain FC between brain regions of the participants33. For the channels of interest A and B, the Pearson correlation coefficient calculation formula was expressed as follows: r = Σ (Ai – Amean) (Bi – Bmean)/(n−1) S(A) S(B)12. In this formula, Ai and Bi denoted the oxygenation activation strength of brain regions A and B at the ith time point, Amean and Bmean represented the mean oxygenation activation strengths of channels A and B, n indicated the number of time points, and S(A) and S(B) indicated the standard deviations of oxygenation activation strengths for channels A and B12,33. The Pearson correlation coefficient matrix was then calculated for all 21 channels of the participants.

Inter-brain synchrony

The unfiltered preprocessing data were imported into MATLAB 2023b and processed using the WTC toolkit to calculate the coherence values. The WTC was used to calculate the wavelet coherence scores for all 21 paired channels of the participants48. WTC was used to assess the temporal relationship of HbO for each pair of participants48, and this method has been widely adopted in previous studies41,42. After obtaining the wavelet coherence values, we performed Fisher Z-transform (Fisher Z-Statistics)10,49. Subsequently, we employed a data-driven frequency band selection method to compare the differences in wavelet coherence values between the two task states12,23,33. The WTC for each task condition was calculated by subtracting the average WTC during rest periods from the WTC during task periods. We then performed a two-factor repeated measures ANOVA on the WTC values, considering both task type (high vs. low interdependence) and peer relationship (friend vs. stranger). The frequency band with significant interaction effects (0.023–0.032 Hz) was identified as the frequency of interest (FOI) (see Fig. 4b). This selection was further validated using a post hoc Bonferroni correction. This frequency band excluded high-frequency and low-frequency noises (i.e., blood pressure at ~0.1 Hz, respiration at ~0.2–0.3 Hz, and heart rate at 1 Hz) and other related physiological noises50,51. Subsequently, to address the issue of multiple comparisons across channels and frequency points, we employed nonparametric permutation tests based on random shuffling52. First, we randomly rearranged each participant’s data by shuffling the order of the two groups to generate new permutation samples23,52. Subsequently, we selected the significant channel 18 and frequency band 0.023 Hz to 0.032 Hz for the WTC calculation and statistical analysis. The permutation test was repeated 1000 times, with each permutation involving random pairing of participants after shuffling their order, followed by the calculation of WTC values to assess their significance23,52. Finally, we calculated the 95% confidence interval for the WTC values obtained from each permutation and reported the significant WTC values within the frequency band of 0.023 Hz to 0.032 Hz. The results demonstrated that the WTC values in this frequency range were statistically significant, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.002, 0.272].

Responses