How gasoline prices influence the effectiveness of interventions targeting sustainable transport modes?

Introduction

The transport sector as a whole is responsible of nearly 25% of direct CO2 emissions worldwide1. A major proportion of these emissions comes from the utilization of individual cars (e.g., 60% in Europe)2. Despite gains in efficiency and policies being adopted, transport is the only sector where greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) have increased in the past three decades1. Both short- and long-term transport mitigation strategies are thus essential to achieve deep GHG reduction ambitions1. Beyond climate change mitigation, the health benefits of reducing car dependency and moving towards public and active transport are well established3,4. This includes, for example, direct benefits through increased physical activity level and indirect benefits via decreased air and noise pollution4,5,6. Accelerating efforts in promoting healthier and more sustainable transport modes, which refers here to reducing car use to the profit of public and active transport, is thus crucial.

Shifts towards healthy and sustainable transport modes are usually promoted by implementing individual behaviour change interventions (i.e., also called soft interventions) and/or by modifying the social- or built-environment with benefits or constraints for users (i.e., hard interventions)7,8. Although results from the literature are heterogeneous, both type of interventions, being implemented independently from each other or in combination, have shown effectiveness in changing behaviours (see9,10,11,12,13 and14 for a null finding). For example, a recent meta-analysis on soft interventions showed that individual behaviour change interventions targeting key psychological variables (e.g., attitudes, beliefs, motives) could lead to an average reduction of 7% in car modal share11. Regarding hard interventions, a study aggregating data from 106 European cities indicated that an average of 11.5 km of provisional bike lanes, built per city during the COVID-19 pandemic, was associated with an increased cycling between 11 and 48%12.

One potentially key factor that has not been yet studied in the literature as a moderator of interventions’ effectiveness is gasoline price15. Gasoline is by far the main source of energy for the transport sector and individual cars worldwide (i.e., around 90%)16,17 and gasoline prices are known to be associated with transport behaviours in correlational studies18. For example, a recent study conducted in the US showed that those who came of driving age during the oil crises of the 1970s, which lead to exceptionally high gasoline prices, persistently drive less to work by car in later life19. The larger literature in transport and economics has shown that higher gasoline prices decrease car use20 and effects are stronger in Europe21,22 than in the US23,24, which may be explained by higher availability of public transport in this region21,25. Higher gasoline prices may therefore improve the effectiveness of interventions targeting healthier transport modes by further pushing people to seek alternatives to gasoline-intensive transport modes18. Yet, our knowledge on the potential role of gasoline prices on the effectiveness of interventions targeting healthier transport modes, both at the worldwide scale and between continents, is still limited despite its important role.

To build upon previous research, the current study aims to quantify the potential role of relative gasoline price (i.e., gasoline price as a ratio of purchasing power), on the effectiveness of interventions targeting healthy sustainable transport modes (both soft and hard interventions). This study focuses on relative gasoline price to account for differences between countries in the final budget of households beyond absolute prices of gasoline. We hypothesize that higher relative gasoline prices, over time and places, are associated with higher effectiveness of interventions targeting healthy sustainable transport modes. Second, given the strong regional differences in local taxes and crude oil supply shocks26, we expect significant differences in the role of relative gasoline prices in transport’s interventions between continents. Third, we expect this effect of relative gasoline price to interact with other important structural determinants of daily transport such as access to public transport, private motor vehicle ownership and access to streets and open spaces (a crucial factor for active transport)27; higher prices leading to higher interventions’ effectiveness mostly in favorable contexts for active and public transport (e.g., higher access to public transport).

To test these hypotheses, the current study takes advantage of the data generated as part of a published systematic review and meta-analysis (i.e., no systematic review was performed as part of this current article, but solely a re-analysis of the identified articles from a previous systematic review)9. This previous study aimed to compare the effectiveness of interventions with carrot, stick, or a combination of strategies on changing travel behaviours including driving, public transport, walking and cycling. The original systematic review performed aimed at identifying controlled before-and-after studies of interventions and travel behaviours in adults from the general population9. Interventions were conducted across Asia, Oceania, North America and Europe and included carrot strategies such as cycle training programs, financial reward for active travel, bike subsidies, modification of the built-environment in favor of active transport, as well as stick strategies, which include increased parking prices, reduced road space for cars or traffic rule restrictions. Most studies (73%) were carrot interventions, 9% were stick strategies and 18% a combination of both. These interventions were implemented at the city level for most of them (60%), and at the neighborhood or workplace level (24 and 16% respectively). The authors from the original systematic review concluded that interventions that combine both carrot and stick strategies were more effective at encouraging alternatives to driving, although the effect was not statistically significant when meta-analyzed9.

Results

Means and precision estimates for the transport outcomes were extracted and converted into standardized mean differences with 95% CIs in the original meta-analysis by Xiao et al. 9. The present re-analysis thus takes benefit of these previous data extraction and transformation steps (see the methods section for further details on the effect sizes). This current meta-analysis includes 52 unique studies and 146 effect sizes after removing one outlier presenting a standardized mean difference four times larger than the sample’s average28. Compared to the original meta-analysis, including 59 individual studies, three studies were removed due to the unavailability of public and open data regarding oil prices or per capita purchasing power for these specific countries and time periods (i.e., Singapore, Colombia and New Zealand)29,30,31. Four other studies were removed because we were unable to identify either the exact time period during which the interventions were implemented and/or because results were reported for several countries together12,32,33,34. Included studies were implemented first in North America (n studies=22; k effect sizes=58; 41%), then in Europe (n studies=18; k effect sizes=46; 35%), Oceania (n studies=7; k effect sizes=20; 14%) and Asia (n studies=5; k effect sizes=22; 10%). Interventions targeted cycling (33%), public transport (21%), driving (17%), walking (16%) and a combination of cycling and walking (13%). Regarding study quality, 25% were rated as strong or high, 37% as moderate and 38% as weak using the Effective Public Health Practice Project tool35 and as coded in the original systematic review and meta-analysis by Xiao et al. 9.

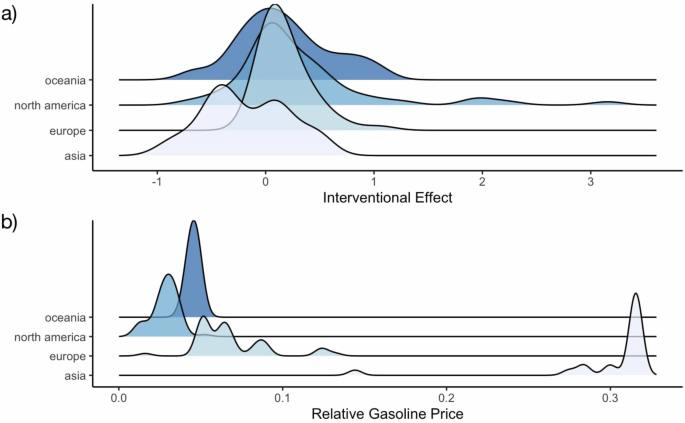

Fig. 1a displays the distribution of the effect sizes for the interventions and the four continents, and Fig. 1b represents the distribution of relative gasoline price across studies and per continent. On average, interventions had a significant and positive effect for promoting healthy sustainable transport modes across all continents and outcomes (0·15, 95% CI 0·02 to 0·28; Fig. 1a). The only significant difference observed between continents was for North America and Asia, with interventions conducted in North America being significantly more effective than interventions conducted in Asia (0·29, 95% CI 0·01 to 0·57). Average relative gasoline price was 0·08, indicating that the price of 1000 liters of gasoline represented on average 8% of the per capita yearly household expenditures for this sample (Fig. 1b). Mixed models highlighted significant differences between average relative gasoline price in Asia (0·26, SD = 0·01) compared to the other continents (North America, 0·03 SD = 0·01; Europe, 0·07, SD = 0·01; Oceania, 0·05, SD = 0·01). A small but significant difference was also found between Europe and North America with higher relative gasoline price in Europe compared to North America (0·04, 95% CI 0·02 to 0·07; Fig. 1b).

a Density plots for interventions’ effect; b Density plots for relative gasoline price; Oceania: N = 7 studies, k = 20 effect sizes; North America: N = 22 studies, k = 58 effect sizes; Europe: N = 18 studies, k = 46 effect sizes; Asia: N = 5 studies, k = 22 effect sizes.

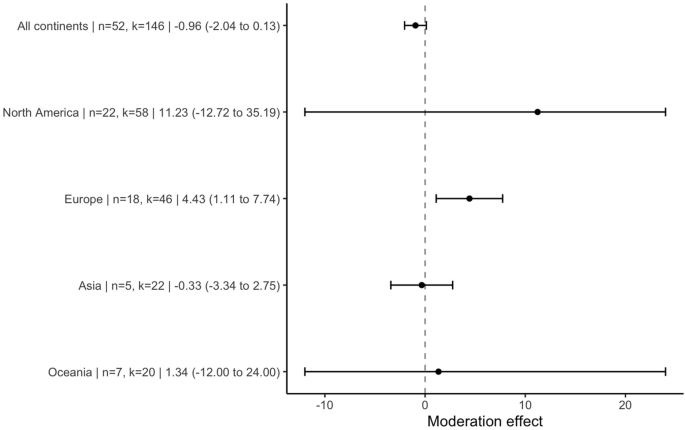

Fig. 2 presents the results of the meta-regressions for the 52 studies pooled together and per continents. This forest plot represents the average moderating roles of relative gasoline price on interventions’ effectiveness with their respective confidence intervals. The moderation effect of relative gasoline price on interventions’ effectiveness was not significant for all the continents merged together as well as for North America, Asia, and Oceania alone. In Europe, however, a higher relative price of gasoline was associated with higher interventions’ effectiveness (4·43, 95% CI 1·11 to 7·74). The effect observed in Europe was robust when excluding studies rating as weak for their methodological quality (5·48, 95% CI 1·43 to 9·52). To investigate whether this effect was driven by gasoline price or purchasing power alone (the two components of the relative gasoline prices score), we performed the meta-regressions with these two variables as two distinct moderators. Both were equal or close to zero (-0·00, 95% CI -0·01 to 0·00 and 0·15, 95% CI -0·26 to 0·55, respectively for purchasing power and gasoline price). The effect observed in Europe was also robust when controlling for the type of intervention as labeled in the original meta-analysis by Xiao and colleagues (i.e., carrot, stick, or combined; relative gasoline price in the adjusted model, 4·65, 95% CI 0·84 to 8·45)9.

Confidence intervals are bounded between -12 and 24 in the forest plot.

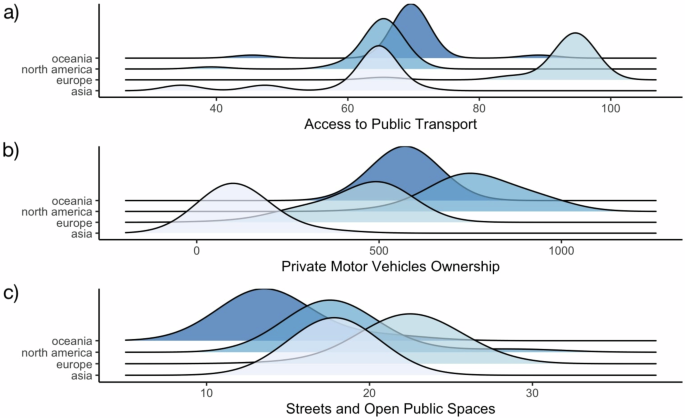

Fig. 3 displays the distribution of the three structural determinants (A) access to public transport, (B) private motor vehicle ownership and (C) access to streets and open public spaces for the four continents. Noticeable differences appear between continents (see the methods section and supplemental results for numerical indicators derived from linear regressions). Europe had significantly higher access to public transport (Fig. 3a) and access to streets and open public spaces compared to the other continents (Fig. 3c). North America showed significantly, higher, and Asia lower, private motor vehicle ownership compared to Oceania and Europe (Fig. 3b).

a Density plots for access to public transport; b density plots for motor vehicle ownership; c density plots for access to streets and open public spaces; Oceania: N = 7 studies, k = 20 effect sizes; North America: N = 22 studies, k = 58 effect sizes; Europe: N = 18 studies, k = 46 effect sizes; Asia: N = 5 studies, k = 22 effect sizes (k = 21 for the indicator “Streets and Open Public Spaces”).

Regarding the interactions with relative gasoline price, we found a significant moderation effect for the interaction with access to public transport (0·05, 95% CI 0·00 to 0·10). The moderating role of relative gasoline price was higher in studies with better access to public transport (i.e., studies above the sample’s mean level for access to public transport; 4·39, 95% CI 1·06 to 7·71) compared with studies with a lower level of access to public transport (i.e., studies below the mean level for this variable; -1·07, 95% CI -2·41 to 0·27). The interactions between relative gasoline price and, respectively, private motor vehicle ownership and access to streets and open public spaces were not significant (0·00, 95% CI -0·00 to 0·01 and -0·05, 95% CI -0·11 to 0·01).

Ancillary analyses (i.e., testing the moderating effect of relative gasoline prices on European’s interventions for the different transport outcomes and exploring the heterogeneity observed for North America) are available as supplemental results (see the methods section and https://osf.io/b9usj/, section 9 of our html output “Ancillary Analyses”). Additionally, following a reviewer’s recommendation, we tested the role of access to public transport, private motor vehicle ownership and access to streets and open public spaces as distinct moderators of interventions’ effectiveness (i.e., not included via an interaction with relative gasoline price). None of these variables had a significant moderating role in interventions’ effectiveness (see https://osf.io/b9usj/, section 7 of our html output “Structural Determinants”).

Discussion

This meta-analysis provides empirical evidence that the relative gasoline price significantly moderates the effectiveness of interventions targeting healthy sustainable transport modes in Europe, but not in the other continents. In Europe, interventions were significantly more effective with higher relative gasoline price over time (i.e., intervention’s period) and across locations (i.e., intervention’s location), regardless of whether the interventions were framed as carrot strategies (i.e., cycle training programs, financial reward for active travel, bike subsidies, modification of the built-environment in favor of active transport) or stick strategies (i.e., increased parking prices, reduced road space for cars or traffic rule restrictions).

The moderating effect of relative gasoline price on the effectiveness of interventions was not significant for North America, Asia, or Oceania, nor when the four continents were pooled together. However, the effect observed for Europe remained robust after controlling for the methodological quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis and the type of intervention (i.e., carrot, stick, or combined)9. We also observed a significant interaction between relative gasoline price and access to public transport across the four continents, with the association between gasoline price and the effectiveness of interventions being stronger in areas with higher access to public transport, as seen in Europe.

As highlighted in a recent systematic review on the determinants of sustainable transport modes15, prices can play an important role in modal shift but mostly in context where infrastructures are available. As shown in the Fig. 3, the European countries and cities where the interventions were conducted had higher access to public transport and higher proportion of streets and open public spaces, as well as lower motor vehicle ownerships than the other continents. Therefore, the result observed for Europe in the present paper is likely attributable to these contextual differences favorable to public and active transport. This aligned with the hypothesis of a conditional effect of relative gasoline price on the effectiveness of transport interventions, with the effect being present mostly when infrastructures allow modal shift15. This finding is further supported by our result showing an interaction between a relative gasoline price and access to public transport. The overall pattern of result corroborates findings from observational studies conducted mostly in North America and showing positive associations between increases in gasoline price and increased active transport, such as cycling to work36,37,38 (see also for non-significant associations)28,39, decreased road traffic40,41 and increased public transport ridership42,43.

This finding has implications for future interventions and practitioners. The transport sector is largely dependent on the availability of relatively cheap gasoline price. This raised concerns about the vulnerability of the transport system in a context of possible long-term increase in crude oil prices due to increased extraction costs related to declining reserves quality26,44. Increased gasoline related taxes can also be chosen as a local or national strategy for climate change mitigation45. This context could accelerate the transition towards more sustainable transport modes in future46. However, to maintain socially fair outcomes in a such context, increases in gasoline price should come with the availability of modal alternatives and fairness in future measures47. Increased taxes, for example, need appropriate policy sequencing and packages/mixes (e.g., binding car use taxation initiatives with public infrastructure development funding)48,49,50,51. As illustrated by our results, appropriate public and active transport infrastructures are needed to accompany planned or sudden changes in gasoline prices (i.e., conditional effects)15. We argue that, in a context of global increase of crude oil price, investing in public and active transport infrastructures, notably in areas with high car-dependence, represents a form of “life insurance” for our societies; the objective being to build the required infrastructures to foster our resilience to current and potential future increases in gasoline prices.

Regarding health outcomes, projected increase in gasoline prices could come with strong health co-benefits in the general population but also negative health effects for individuals with high car dependency52. As hypothesized in the current study, higher gasoline prices may improve the effectiveness of interventions targeting healthier transport modes by further pushing people to seek alternatives to car. For example, a study quantifying the health benefits of physical activity generated by active transport on all-cause mortality in a French energy transition scenario with fewer utilization of fossil fuels showed a potential reduction of 9797 annual premature deaths in 2045 and a 3-month increase in life expectancy in the general population53. In car-dependent context however, and if alternatives are not available, lower-income households might be forced to absorb higher gasoline price by limiting travels for social purposes or cutting expenditure in other areas like home heating or food, which would have severe implications in terms of mental-health and well-being54; implications that should be monitored and mitigated in future studies investigating the interplay between gasoline price and transport related behaviours.

Results from this meta-analysis provide a global evidence base on the role of gasoline prices in interventions targeting transport-related behaviors. However, there are several limitations inherent to this work. Given the broad scope of the study, which includes research conducted across four continents and over twenty years, we encountered difficulties in obtaining high-resolution data that is comparable across continents for our three moderators: access to public transport, availability of streets and open public spaces, and motor vehicle ownership. These factors could be estimated more accurately in more focused contexts (i.e., at the scale of a country or a single continent) or by developing more precise databases. Similarly, other cultural and economic moderators, such as car-related attitudes or social norms, could be explored in narrower contexts. This could help interpret the high heterogeneity observed in North America and Oceania (see also our ancillary analyses in the supplemental results). Second, as noted in the original work by Xiao and colleagues9, few studies included in the meta-analysis reported socio-economic status. However, as previously mentioned, accounting for this variable is crucial for future research investigating the moderating role of gasoline price in interventions54. This study is limited to using country-level or state-level data (in the US) for purchasing power and cannot account for income disparities within countries. With the advancement of open science practices and the increasing availability of data from individual interventions, individual participant data (IPD) meta-analyses could more accurately explore the impact of income levels and disparities on the relationship between gasoline prices and the effectiveness of interventions. Third, no studies from low- and middle-income countries, or from African and South American countries, were included in the current meta-analysis, and only a few studies were available for Asia. This limits the generalizability of our findings. It is also worth noting that we could have explored grouping factors beyond continents. For example, studies could have been pooled using empirical thresholds for structural moderators, such as the first tertile of access to public transport. Fourth, our results for Asia and Oceania should be interpreted with caution due to the potential lack of statistical power for these two continents (i.e., only five and seven individual studies, respectively, with around 20 effect sizes were available). This is especially true for Oceania, where the confidence intervals are notably wide. Fifth, although our study does not focus on electric mobility, future research could examine whether, and under what conditions, relative gasoline prices encourage a shift from oil-powered to electric vehicles. Sixth, we did not conduct a systematic review for this study, but instead used recent data from the literature. As a result, our findings may change if a more comprehensive or updated set of primary interventions is included in future analyses.

Finally, this study used a measure of relative gasoline prices adjusted for purchasing power, rather than using gasoline prices alone as in most previous studies18. This approach allowed us to pool and compare studies from multiple countries, whereas previous observational studies have primarily focused on single locations18. Adjusting gasoline prices for purchasing power at the country or state level reflects evidence from the literature, which shows that vulnerability to rising gasoline prices is likely higher in populations and areas with fewer economic resources55. In future studies pooling data from different socio-economic contexts (both within and between countries), relative gasoline prices, rather than raw gasoline prices, should be preferred.

In conclusion, this study suggests that relative gasoline prices can significantly moderate the effectiveness of interventions targeting transport-related behaviors, with higher intervention effectiveness observed in times and places with higher relative gasoline prices. However, this effect was only seen in Europe. We interpret this result as a conditional effect, where relative gasoline prices interact with the availability of infrastructure that supports a modal shift from cars to active and public transport. In the context of rising global crude oil prices, potential supply difficulties in some regions, and climate change mitigation efforts, increased gasoline prices could accelerate the transition toward healthier transport modes. However, this positive outcome should be accompanied by substantial investments in infrastructure that supports alternatives to car use.

Methods

In response to the reviewer’s suggestion, we have created a table summarizing the types of data used in the manuscript along with their respective sources (see the file ‘Data Sources’ at https://osf.io/b9usj/).

Transport outcomes

Transport outcomes included changes in (i) driving, (ii) public transport usage (iii) cycling, (iv) walking, or a combination of cycling and walking, labeled here as (v) active travel. These variables were expressed as: modal share (i.e., the percentage of travelers using a particular type of transport or number of trips using said type before and after the intervention); duration, frequency and distance of trips measured with self-reported diaries or more objective methods such as GPS and accelerometers; as well as counts for bike paths or bike share systems usage. Means and precision estimates for these outcomes were extracted and converted into standardized mean differences with 95% CIs in the original meta-analysis by Xiao et al. 9. The present re-analysis thus takes benefit of these previous data extraction and transformation steps. The only modification we operated was to transform the estimate for driving, so a positive effect size for driving indicates a reduction of driving after the interventions. This was done to analyze all outcomes together in the meta-analyses. Therefore, positive effect sizes in the present study indicate an increase in cycling, walking, public transport usage and a decrease in driving.

Relative gasoline price

Relative gasoline price, was defined as the ratio between the price of one liter of gasoline and the purchasing power per capita for a given country and time period. When an intervention was implemented over several years, gasoline price and purchasing power were averaged for the specific time period. Studies were excluded if information was missing for a specific country and/or time period, impeding the computation of a score. For example, a relative gasoline price of 0.08 in France in 2015 indicates that, for this specific year, the price of 1000 liters of gasoline -which represents 2.7 l/day- represented 8% of the per capita yearly household expenditures.

To build this moderator we first retrieved gasoline (petrol) price in euro (2018) per liter from the European Commission for the period 2008-201956. These values were then converted to United States (US) dollar 2018 to allow comparison between continents. For the US, data retrieved from the European Commission were complemented with city-level or regional data from the Federal Reserve Economic57 and the Energy Administration Information58 databases to account for price differences within the country. Second, purchasing power for each specific country and time period was retrieved from the World Bank database59 and, the Bureau of Economic Analysis for the US60. Purchasing power was expressed as final consumption expenditure by households in 2018 constant US dollar. Third, purchasing power per capita was obtained by dividing household expenditures by population data from the World Bank61. Fourth, the relative gasoline price was obtained by dividing gasoline prices by purchasing power per capita. Finally, to ease interpretation of this score, this relative gasoline price was multiplied by 1000.

Structural determinants and control variables

To test potential interactions between relative gasoline prices and structural factors associated with transport behaviors, we retrieved data for population (i) access to public transport, (ii) private motor vehicle ownership and (iii) access to streets and open spaces.

For public transport accessibility, we used the United Nations Urban Indicators database62 providing the estimated share of urban population who can access a public transport stop within a walking distance of 500 meters (for low capacity public transport systems) and/or 1000 meters (for high capacity public transport systems) along the street network. This outcome is expressed as a percentage, with higher values indicating better access to public transport. Second, private motor vehicle ownership per 1000 inhabitants was retrieved from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development database63. Higher values indicate higher proportion of the population owning a private motor vehicle. Third, the estimated share of urban areas in both streets and open public spaces were retrieved from the United Nations Urban Indicators database64. This outcome is expressed as a percentage, with higher values indicating higher share of streets and open public spaces. According to the United Nations Urban Indicators database, the share of land that a city allocates to streets and open public spaces is not only critical to its productivity, but also contributes significantly to the social dimensions and health of its population. The size, distribution and quality of a city’s overall public space act as a good indicator of shared prosperity. Data for these three variables were available at the city or country level (we also used Europe’s average for the share of urban areas in both streets and open public spaces for few European countries with missing information at the country level).

Additionally, sensitivity analyses were performed to test the impact of studies’ methodological quality (using the Effective Public Health Practice Project tool35) on our outcomes. We also controlled for the role of gasoline price and purchasing power separately (the two components of the relative gasoline price variable). Finally, we also controlled for the distinction between stick, carrot or combined interventions investigated in the original meta-analysis9.

Data analyses

To quantify the role of relative gasoline price on interventions’ effectiveness (hypothesis 1), we performed a series of multi-level meta-analyses and meta-regressions. The multi-level option was preferred to handle dependency in effect sizes within studies (i.e., several effect sizes per study). This multi-level option considers three different variance components: the sampling variance of all the extracted effect sizes, the variance between effect size extracted from the same study and the variance between studies. In the current article, the main outcome (i.e., effect size) was the standardized mean differences extracted from the interventions (i.e., changes in transport outcomes). The meta-analyses were therefore fitted to account for the variance of all the extracted effect sizes together with the variance within- and between-studies. In the model, a continuous moderator was included to estimate the role of relative gasoline price in interventions’ effectiveness (i.e., change in standardized mean differences).

Because we expected differences between continents, we performed the meta-analyses for all the effect sizes together but also separately for North America, Europe, Oceania and Asia (hypothesis 2). Finally, we created three interaction terms, between relative gasoline price and (i) access to public transport, (ii) private motor vehicle ownership, and (iii) access to streets and open public spaces which were then entered as moderators of interventions’ effectiveness in the models (hypothesis 3), in place of relative gasoline price in the models tested for the hypotheses 1 and 2. Interaction terms were created by centering each variables (i.e., relative gasoline prices and the three structural determinants) and then multiplying the variables (i.e., relative gasoline prices * access to public transport; relative gasoline prices * private motor vehicle ownership; relative gasoline prices * access to streets and open public spaces).

Responses