Promoting sustainable cities through creating social empathy between new urban populations and planners

Introduction

Empathy is the ability to see the world through the eyes of others and has been argued to be a key social and psychological mechanism to reinforce pro-social and pro-environmental behaviour1,2. Brown et al.1 propose that empathy is a pre-requisite of sustainable interactions with the natural and social environment: empathy, through an emotional connection with living and non-living beings, acts as a moral impetus for positive action. The phenomenon of social empathy means concern for others based on socio-economic disparity and inequality in contemporary society3. The prevalence of social empathy suggests that empathetic individuals who occupy positions of power or decision-making, can translate their empathy into action, and can contribute to public policies that are appropriate, useful and responsive to the needs of otherwise underserved groups3. Social empathy can also lead to empowerment, and people who feel empowered are more likely to take action and exercise their agency to transform existing social conditions4. Hence empathy between actors in settings such as urban planning could be central to the achievement of commonly held aspirations for sustainable settlements.

Perspective taking has been applied to build empathy in the context of asymmetric power relations between social groups5,6. Specifically, it has been used as an approach for reducing prejudice towards and fostering the inclusion of migrants and refugees in host communities7,8, and it has also been applied in the context of planning to improve community support for infrastructure development9. Through perspective taking, people become more empathetic towards others and attach greater value to their wellbeing10. Despite this potential to foster empathy between policy stakeholders and marginalised groups, the direct engagement and deliberate design of taking others’ perspectives is not widely used in formal ways in the context of urban planning and migration.

Ensuring sustainable cities means ensuring the effective and timely integration of new populations into the planning and implementation of sustainable living, particularly for fast growing urban places that are increasingly impacted by climate change. According to projections, around five billion people will live in cities by 203011. This rapid urbanization is often associated with the emergence of new economic sectors and opportunities in urban centres. Moving to cities has been shown to provide a pathway out of poverty, not least with rural economies globally becoming more precarious due to variable investment, growing under-employment and resource constraints and even climate risks12,13,14. Migration in effect drives growth in urban economies through expanding labour resources, the taxation base, as well as by bringing innovation and trans-local linkages15.

While moving to cities undoubtedly presents new opportunities for migrants and their households, they often exchange one set of hazards for another. Cities are also affected by the adverse impacts of climate change: 59 percent of urban areas with populations over half a million globally have experienced cyclones, floods, droughts, earthquakes, landslides and volcanic eruptions16. The number of people exposed to environmental hazards and extreme weather events in cities is projected to rise as a result of intersecting urbanisation and climate change processes17, and low-lying coastal cities, which are often densely populated, will be particularly hard hit18. Most low-income migrants in cities are relegated to informal settlements on marginal land and insecure livelihoods in the informal economy, making them disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards, and subject to multiple rights violations19. They live in constant fear of eviction, and struggle to access basic services such as water, sanitation and hygiene, cooking gas, electricity, healthcare and education20, while they lack support networks and enjoy limited recourse to safety nets and social protection21. Such precarious living and working conditions are exacerbated by the wider political economy of urban informality22,23 and by exclusionary policy and planning processes that are based on prejudice against migrants24,25,26. For example, household registration systems (such as the houkou system in China, or ho khau in Vietnam) often prevent migrants from accessing services or exercising their political rights in cities, because they retain their rural household registration status even after moving. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many interstate migrants in Indian cities could not obtain rations because they were still formally registered at their rural homes27. Despite their high socio-economic vulnerability and exposure to environmental hazards, migrants are also routinely excluded from development, adaptation, and disaster risk reduction planning, both in terms of their lack of participation in these as well as through their unique needs, vulnerabilities and capacities not being considered28.

Exclusion from public services and decisions about planning for climate action and disaster risk reduction has been shown to reinforce the root causes of climate-vulnerability in urban settings, thus undermining efforts to build sustainable cities29,30. This is a missed opportunity, because beyond benefitting urban economies as sources of labour, under inclusive policies, migrants have the potential to drive innovation and contribute to solutions that tackle urban sustainability challenges. Migrants’ traditional knowledge, practices and beliefs transported to their urban destinations can facilitate everyday actions and behaviours that address urban sustainability challenges. For example, migrants’ previous experiences of resource scarcity have been shown to motivate behaviours aimed at resource conservation at their destination31,32. Key factors that facilitate the role of migrants as sustainability actors in cities include providing access to infrastructure, facilitating the development of place attachment, and actively engaging with migrants and their religious or cultural organisations30,31.

The participation of diverse actors in urban planning can be an important first step towards addressing the multidimensional and multilevel persisting inequalities that impact urban sustainability33. But how can citizen participation translate into lasting transformative change and sustainable solutions to urban challenges? Here, we propose social empathy as an effective mechanism that can lead to socially more just and inclusive policies and programmes through enhancing cognitive engagement and emotional affective positive response between actors. Participatory urban planning can act as a platform for advancing citizen’s rights by giving people an opportunity to shape decisions that will affect them. It can provide a deliberative space where multiple concerns can be heard and acted upon by those in positions of power, as well as it can facilitate partnership between different actors34.

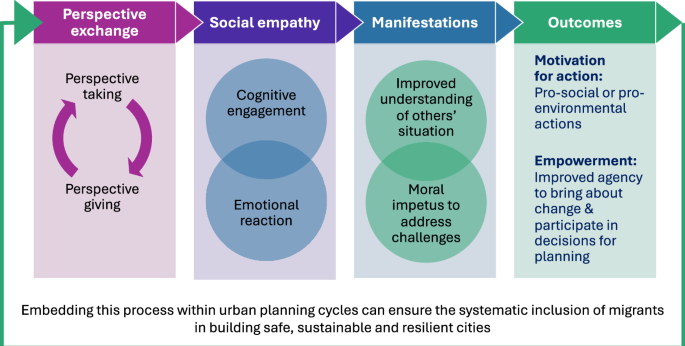

The study involves intervening to build empathy directly—in that sense it involves action research—among planners and migrant communities in Chattogram, Bangladesh, in order to shape sustainability plans and outcomes. The study recruited a cohort of planners and a separate cohort of adult recent migrants to the city and worked with them to create consensus around practical changes in city planning and regulations, using methods designed to maximise opportunities for perspective exchange, consisting of perspective giving and perspective taking (Fig. 1). Details are in the Methods section.

Building social empathy through perspective exchange between migrants and urban planners can foster more just and inclusive solutions to urban challenges that enhance urban sustainability.

Results

Photovoice and photo-elicitation involving urban planners and migrants in the rapidly growing city of Chattogram, Bangladesh, showed that initially, planners and migrants had different perceptions about what they considered to be the most pressing issues and the scale at which they perceived these. However, these diverging perspectives converged through perspective exchange, which allowed participants to reflect on each other’s situation, evoking a sense of feeling empowered among migrants and instigating motivation to act among planners (see Fig. 1).

Perspective exchange on urban security and sustainability

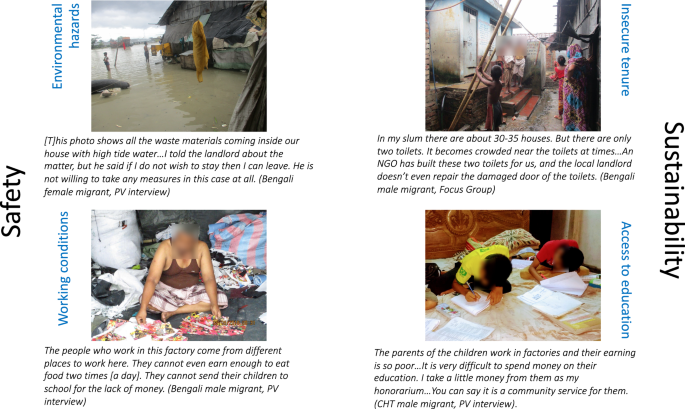

Migrants focused on things that were more proximate to where they lived and worked in cities and thus had a direct impact on their and their community’s multidimensional wellbeing and security (see Fig. 2). Water logging and working conditions were identified by all migrants as major risks for health and safety, while precarious housing and access to education and services such as water and waste collection were considered to be the main factors undermining the sustainability of their communities in their urban migration destinations.

The figure is the authors’ own elaboration—the photographs featured in the figure were taken by study participants for the photovoice activity (Prior informed consent was obtained from participants for the use of photographs in publications).

By virtue of living in informal settlements, illegally constructed on marginal land such as low-lying riverbanks, migrants are disproportionately exposed to water logging. The polluted water, which regularly inundates their streets and homes, acts as a health and safety hazard; a source of injury and water-borne disease. Assets are damaged when homes are submerged and water logging also limits migrants’ mobility directly and indirectly, including by imposing additional costs on movement. Since informal settlements fall outside the remit of urban planners and service provides, migrants are powerless and at the mercy of their landlords. Although some migrants have raised the issue with their landlord, they declined to implement improvements to make houses more resilient to water logging.

Many low-skilled migrants are doing jobs that higher-class people would not do and face unfavourable terms and harsh physical working conditions, resulting in precarity that keeps migrants locked into a cycle of poverty and marginality. These work environments pose a range of health and safety risks, through exposure to hazardous materials, substances, and bacteria. They often work without appropriate training or safety equipment, for long hours with very few breaks on building construction, in sawmills and factories, some of which also employ under-aged children. Others work as hawkers, waste pickers or rickshaw operators, barely making ends meet. They are trapped in these conditions due to their lack of skills and qualifications, coupled with their obligation to support their family in the city and in their places of origin.

Precarious housing and constrained access to education are key risk factors that undermine migrants’ long-term wellbeing and resilience in cities. Precarious housing is manifest as insecure tenure on illegally occupied land, high rents, densely populated neighbourhoods, and limited access to civic services (such as water, cooking gas, toilets). Although there has been some effort to provide basic facilities such as piped water, corruption is a major challenge and acts as a barrier to interventions reaching those in need. The main perpetrators are landlords and other ‘middlemen’ who capture public facilities for their own gain.

Access to education is key to building sustainable lives in the city. Poverty emerged as a prominent barrier which excludes migrant children from schooling and pushes them into under-aged work, while it keeps adults locked into low-skilled and poorly paid hazardous jobs. Migrants raised concerns about the security risks associated with leaving young children unattended at home while they were working. Rather than being powerless, however, skilled migrants highlighted their own role in supporting the education of migrant children and considered this as a service to their community. They can step in where educational facilities are absent in informal settlements.

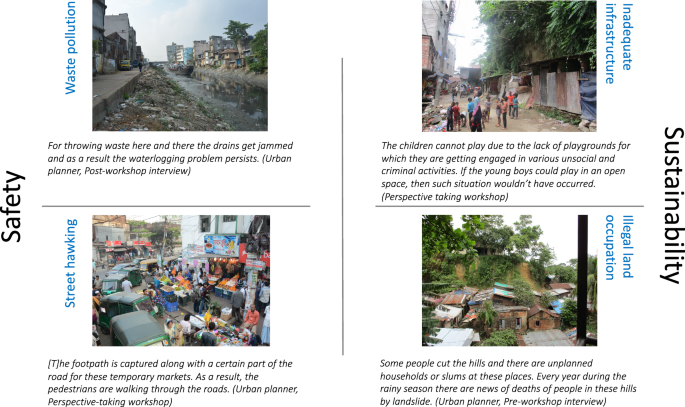

Planners were more preoccupied with issues at a city-wide scale, emphasising their impact on the entire urban population, as well as the challenges they posed to them in their professional capacity (see Fig. 3). They highlighted waste pollution and street hawking as key risks to urban safety and emphasised their knock-on effects on other risks and hazards, such as water logging, traffic congestion and disease. They blamed waste pollution and open dumping on residents’ behaviour and lack of awareness about the consequences which, they claimed, have also undermined earlier initiatives for waste collection and recycling introduced by Chittagong City Corporation. Planners described street hawking as a risk to road safety due to congestion and the obstruction of traffic. Albeit some admitted that street hawkers provide an important service to city dwellers which they also use, since their goods are usually cheaper and fresher.

The figure is the authors’ own elaboration—the photographs featured in the figure were taken by study participants for the photovoice activity (Prior informed consent was obtained from participants for the use of photographs in publications).

Alongside risks to urban safety, planners identified illegal land occupation and inadequate infrastructure as the main factors that can jeopardize urban sustainability. Illegal land occupation, especially of hill slopes and waterways, was seen by planners not only as a major safety hazard for low-income migrants but also as a sustainability hazard for the wider city. Such illegal occupation exacerbates other risk factors such as water logging and poses a challenge for planners in developing and implementing sustainable urban infrastructure. Planners considered inadequate or poor-quality infrastructure as the root cause of many sustainability challenges in the city. In addition to the plethora of risks to urban safety and sustainability, planners also highlighted city beautification measures such as footpath creation, street lighting, and green open spaces as important sources of wellbeing and sustainability, which can benefit all urban dwellers.

Building empathy through perspective exchange

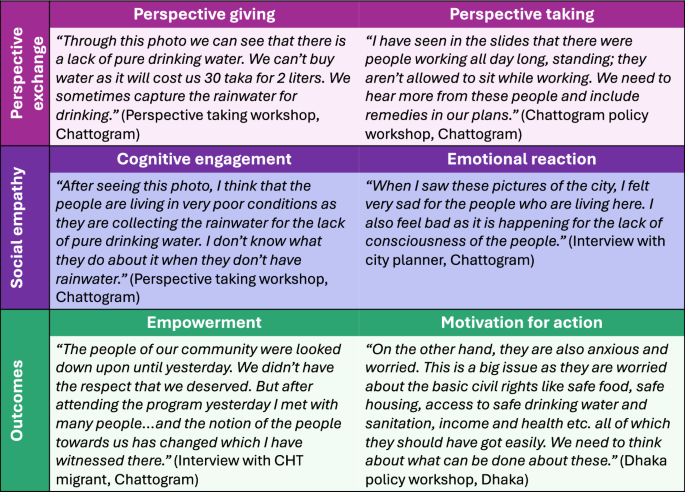

Perspective exchange with the help of photographs encouraged planners and migrants to reflect on each other’s situation and viewpoints. This facilitated building cognitive and to some extent emotional empathy. Cognitive empathy involves understanding other people’s circumstances and emotions while emotional empathy entails identifying with the emotional state or reaction of others at a deeper level35.

Cognitive engagement

Through taking the perspective of migrants, planners gained an appreciation for the challenges migrants face due to unmet basic needs and rights. They empathised with the precarious situation of migrants and recognised their importance to urban economies as sources of labour. They also highlighted the essential service they provide for urban society, doing work that others would not do. They acknowledged that migrants are often disempowered by their marginality and precariousness, which render them invisible to government actors. They highlighted the absence of targeted policy action and migrants’ invisibility in policy and planning. They pointed out that migrants often lack choice and agency about where they live and where they work, because they do not have the means to escape informal settlements and the informal economy. Their invisibility and marginality are, in turn, exploited by some private actors (e.g. landlords, landowners, employers, informal service providers), exacerbating the precarious situation of migrants.

Emotional reaction

Planners’ emotional reaction was often invoked by their reflection on their own situation—recounting their or their parents’ experiences of migration. The realisation that they are also migrants helped them relate to the situation of low-income migrants in the study. It led them to conclude that they are not that different, as well as to realise that their privilege (better socio-economic status, higher level of education and professional standing) places them in a position where they can take action to support less fortunate migrants. They displayed a sense of sadness and regret upon seeing the everyday trials and tribulations of migrants living in informal settlements. They used emotive language to communicate their reaction to migrants’ photographs, such as feeling sad, and considered their conditions inhumane.

From empathy towards improved outcomes

The perspective exchange activities instigated a gradual shift in the positioning of blame. Planners displayed increased motivation to act to secure the rights and wellbeing of migrants in cities, while they also highlighted some of the challenges that constrain their capacity to implement positive action. Migrants discussed feeling more empowered through being heard by planners (see Fig. 4).

Perspective exchange fosters empowerment for migrants and motivates planners to act.

Motivation for action

At the outset, migrants and planners had different opinions about who should be held accountable for urban challenges and who should be responsible for their solutions. Migrants blamed service providers, which included government authorities but also the private sector, including powerful informal actors. While initially, planners attributed urban challenges to inappropriate human behaviour, at a closer examination of these issues through a discussion of photographs with migrants, they acknowledged that migrants are often disempowered and caught between private and state actors. They are invisible to government actors, or seen as sources of problems, and are at the mercy of powerful informal actors and other private sector stakeholders who often exploit migrants’ invisibility in policy circles. Thus, a third group of stakeholders emerged through these discussions: the private sector, in particular landlords and employers.

Through empathy building, planners demonstrated an improved understanding of migrants’ situation in urban informal settlements and informal economies and developed a greater recognition of their position of power and ability to advocate on behalf of migrants to solve urban challenges that have implications for urban society beyond informal settlements. They expressed motivation to take action to address some of the issues raised by migrants. Confirming the willingness and commitment of city-level decision makers to work towards transforming the lives of marginalised urban populations, including migrants, is evident in plans to use photovoice by urban planners at Chittagong Development Authority (CDA) in the upcoming city Master Plan.

Empowerment

Following their participation in the perspective taking, and to some extent in the local and national policy workshops, migrants felt more empowered. Through being listened to during the workshops and having the opportunity to raise their concerns with planners and decision-makers who they did not think they would meet, left them feeling more visible, respected and heard.

While planning stakeholders who took part in the city-level and national policy workshops highlighted a number of challenges which limit their power and capacity to successfully tackle urban safety and sustainability challenges that also impact low-income migrants. First, the absence of coordination between different city-level sectoral authorities, which often filter down from a similar lack of coordination and coherence between national level policies or ministries. Second, city-level agencies also face challenges with providing certain services to urban residents if these are outside of their mandate. Third, that city-level agencies are implementers of plans, policies and laws made at the national government level, and they have very little power to shape these. Workshop participants called for greater coherence and coordination between different sectors and different levels of governance, to empower them to implement interventions that target the concerns of migrants.

Despite the prevailing structural challenges that affect urban planning, city-level policy actors and planners also exercise their discretion over the provision of some urban services. For example, a representative of Chittagong City Corporation (CCC) highlighted that despite health and education falling beyond their official remit, they provide health services and educational facilities in the city. They are not supported by the relevant ministries, because they do not recognize the CCC as their implementing organisation.

Discussion

While rapidly growing cities everywhere are undoubtedly grappling with intersecting social, economic and environmental challenges in an era of accelerating climate change, they are also potential sites of experimentation and innovation. Cities have the potential to lead transformative climate action that redresses injustices that exacerbate climate vulnerability in urban areas. This requires the participation of diverse groups of citizens in urban planning34. In cities that are more inclusive and empathic to different needs and experiences, citizens go from being passive receivers of services to active agents in the process of urban governance36. Involving marginalised groups, such as low-income migrants, in decision-making can potentially also act as a first step to addressing procedural and recognition dimensions of justice as a pre-requisite for tackling the root causes of climate-vulnerability and enduring inequalities in cities33,37,38.

Building on Segal’s3 conceptualisation of social empathy and insights from participatory urban planning approaches and experiments34,36,39, we implemented participatory action research towards building empathy between low-income migrants and urban planners in the rapidly growing city of Chattogram, Bangladesh. While planners and migrants emphasised different urban safety and sustainability challenges, their overall diagnosis resonated with earlier studies in Bangladesh, which included insecurity of employment, incomes and housing tenure and constrained access to essential services such as healthcare, education, and water and sanitation, as well as exposure to environmental hazards40,41,42. A recurring theme in both migrants’ and planners’ narratives was the role of private sector actors, such as landlords, informal sector employers, service providers and other intermediaries, in reinforcing urban precarity. Because the formal sector is either not able or unwilling to meet the demand for housing and services, the private sector steps in to fill this gap43. However, as we have seen in Chattogram, these actions are often guided by profit-seeking ambitions. Banks and colleagues have found that the divide between formal and informal economic actors can be elusive, as political elites and employees of government agencies are often closely linked to private actors, such as service providers and local leaders, who operate within the informal urban economy22,23,44. Nonetheless, the private sector can also play a positive role, for example, by providing vital services in informal settlements39.

These insights call for bottom-up resilience building approaches that engage with the nuances of urban political economy, pay heed to the complex relationships between various actors who operate in the formal and informal economy, and reflect the lived realities and context-specific knowledge of urban residents. Yet, most resilience-building in cities remains restricted to making physical infrastructure resilient and neglects political and economic relationships and interest that shape urban governance38. Our findings reinforce that, in addition to exposure to environmental stressors, poverty, marginality and powerlessness are at the root of vulnerability among residents of urban informal settlements45. Despite this, there is no comprehensive policy to address urban poverty in Bangladesh and migrants are regarded either as sources of problems or sources of labour in most urban development policies46. In turn, policies and processes that fail to integrate the voices of low-income urban migrants create exclusionary cities that breed vulnerability and undermine meeting the ambitions of the UN’s Agenda 2030 and New Urban Agenda47.

The study further highlights current legal and policy frameworks that underpin urban planning often fail to recognize the role of local actors in planning and thus fail to create the conditions for enabling their participation. In addition, urban planners and policy actors are also challenged by the lack of sectoral coherence and coordination at the national policy scale, which in turn has implications for their capacity to tackle urban sustainability issues. Taking a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach48 to urban planning can help overcome these constraints. This involves improved vertical and horizontal coordination in the context of multilevel governance of which urban planning and governance is part, and building partnerships between the public and private sector, civil society, international organisations and urban citizens.

This participatory experiment in Chattogram also shows that social empathy can act as an effective pathway towards improved urban sustainability by addressing the gap between marginalised groups and decision-makers. We show that low-income migrants are capable of imagining and articulating alternative or desired urban futures and can play an active role in eliciting solutions to contemporary urban challenges. This resonates with participatory research with low-income marginalised groups in other cities49,50. Indeed, experiences from earlier research in cities have demonstrated that participatory planning presents an opportunity for reorienting power relationships in cities and for redefining urban citizenship50,51. Improved participation in planning and decision-making processes can reinforce resident’s rights to the city and facilitate urban climate justice through improved recognition and participation in urban planning, including plans concerning adaptation and disaster risk reduction, which can then lead to a more equitable distribution of rights, responsibilities, benefits from interventions, as well as social and environmental risks37,52.

Participatory urban planning can act as a vehicle for building just and sustainable cities for all by breaking down existing power asymmetries between decision-makers and some of the most vulnerable groups in cities such as low-income migrants. There is need for more improved participation in decisions in urban planning concerning urban development, climate adaptation or disaster risk reduction as a first step to confronting the structural causes of vulnerability among low-income populations in informal settlements. Importantly, building social empathy through participatory processes can help redress injustices in the way social and environmental hazards are distributed in cities, and can bring the voices of migrants—and other disadvantaged groups—into discussions about the future of rapidly growing cities. Policy and planning stakeholders who empathise with migrants’ situation can use their discretionary agency to instigate positive change and a shift in dominant discourses about migrants in the city. Building social empathy through participatory processes can thus pave the path to more inclusive and sustainable cities as part of long-term strategies towards urban sustainability.

Methods

Participatory action research for promoting urban sustainability

Creative and participatory methods and approaches have been proposed as capable of instigating dialogue between groups that are otherwise unlikely to interact due to differences in power and socio-economic status21. Participatory action research involves researchers and participants working together to achieve social transformation, often through knowledge co-production, reflection on lived experiences and issues affecting different stakeholders, and action directed at amplifying the voices of previously marginalised groups through dialogue or deliberation53.

A variety of participatory approaches, incorporating creative and visual methods such as film and photography, have already been implemented with marginalised communities in urban settings to bring previously unheard voices and overlooked perspectives into city planning, urban design, and to foster empathy in culturally diverse settings20,54,55,56. While challenges have been noted by those employing such approaches, including those relating to power asymmetries and ethical concerns about whose voices are heard, the benefits are also notable. For example, projects that used principles of empathic design and incorporated the specific needs and preferences of refugees into housing plans, have been shown to be socially and culturally more sustainable, and the process deemed empowering for both the architect and the communities involved56.

Building on these experiences, this study created a participatory platform for a two-way exchange or dialogue between planners and migrants. This entailed a process of perspective exchange guided by Segal’s3 three-tiered model of social empathy framework to encourage critical reflection on the situation of others. According to Seagal3, exposure enhances awareness about the differences between and among people and can take place through media or through direct interaction with people who are different from us. Second, explanation is a critical engagement with the differences one’s been exposed to, and it affords a deeper understanding of the situation through asking questions rather than merely receiving information. Finally, experience constitutes the deepest level of engagement, and it involves actually participating in the lives of others and experiencing their day-to-day realities first hand. We explored whether the process of perspective exchange can facilitate social empathy.

Engaging migrants and urban planners in empathy building

The project involved low-income migrants and city planners in an in-depth action research process over 18 months, in Chattogram, Bangladesh (Tables 1 and 2). The city demonstrates common traits to many rapidly growing cities in Asia and beyond. Chattogram is Bangladesh’s second largest city, is a coastal industrial port, with major expansions in manufacturing sectors, a growing population through inward migration, and major environmental challenges. It is often exposed to extreme events such as cyclones, tornadoes, and other environmental hazards such as landslides, which are compounded by significant air and water pollution57. The city attracts migrant workers from different parts of the country58, especially from rural areas, including ethnic migrants from Chittagong Hill Tracts59. The city has undergone rapid growth, which was in part driven by migration and in part by natural population growth60. Its metropolitan area exceeded four million inhabitants in 2011, a trend that is set to continue until 2025 when the city’s population could reach 6.8 million57. At present, over 60 percent of Chattogram’s population are migrants61 who mainly live in informal settlements where they lack access to services and are disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards such as water logging and landslides41. There are more than 2000 informal settlements in Chattogram housing around 1.8 million of the city’s poor41.

Participants were recruited by the Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU) who already had established contacts with low-income communities and urban governance organisations through past research. Urban migrants were recruited from informal settlements in Chattogram which are known to have a high concentration of migrant populations who make a living in the informal economy or by working in low-income occupations in the city’s Export Processing Zones and ready-made garment industry. Maximum variation purposive sampling allowed us to select participants with direct lived experience of urban insecurity62, both as migrants and as planners living in the city. This sampling approach was chosen to capture a diversity of experiences across gender, age, ethnicity, length of residence and occupation types. The research also included ethnic minority migrants from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) area, the largest ethnic minority living in Chattogram57. Initially, engaging and earning the trust of ethnic minority migrants posed a challenge. However, successfully persuading community leaders has facilitated reaching these participants. Participating urban planners represented key organisations responsible for planning and city governance, such as the Chittagong City Corporation (CCC) and the Chittagong Development Authority (CDA). Migrants and planners took part in the project on a voluntary basis, and they were not offered any financial incentive in exchange for their participation. However, to facilitate their participation, the project covered their travel and subsistence costs. Prior informed consent was obtained from participants in writing for the use of anonymised research data in publications, including photographs. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Exeter, and informed consent was sought from all participants.

The action research consisted of a three-phase process: photovoice, perspective exchange workshops, and policy workshops. First, all 17 participants (ten migrants and seven planners) were invited to take part in photovoice, in order to develop an understanding of their lived experiences of life in rapidly growing Chattogram. Photo-based approaches can create shared insights and can help uncover multiple meanings of specific life experiences, places and the social forces that shape meanings63. Following an initial meeting with researchers and camera training, which was attended by all participants, they were asked to take photographs of their everyday life and habitual activities over a period of two weeks before taking part in in-depth photo-elicitation interviews64,65. They then thematically ordered the photographs using their own criteria during a pile sorting exercise and were then invited to explain their rationale for the resulting themes during a photo-elicitation interview. As such, the photos were used as visual stimuli for the elicitation of personal narratives about places, events and phenomena to identify issues that affect the multidimensional well-being of low-income migrants and urban planners and that may have implications for urban sustainability.

Second, the 17 participants were brought together during a bespoke perspective exchange workshop, to encourage dialogue between city planners and migrants using the visual images as catalysts for building empathy through taking each other’s perspectives during a facilitated discussion. Visual stimuli such as photographs can be an effective medium for evoking emotional engagement with the predicament of other living and non-living beings66,67. Earlier work on urban insecurity using photo-elicitation has also demonstrated that photos can be a tool for challenging stereotypes in policy discourses about marginalized or minority groups65. The workshops were preceded by preparatory focus groups with the seven planners and ten migrants, including a separate workshop with ethnic minority migrants. These were an opportunity for participants to become familiar with the perspective exchange approach and to discuss key issues that they wished to raise with their counterparts. The perspective exchange workshops created a safe space for identifying urban sustainability challenges and proposing solutions that reflect the lived experiences of otherwise marginalised populations. To evaluate the experience of perspective exchange, follow-up interviews were also conducted with a sample of city planners and migrants. They invited interviewees to reflect on the perspective exchange activity, and in the case of planners, suggestions were sought for key policy stakeholders to be invited to the policy workshops.

The third phase consisted of two policy workshops at city and national levels. Their aim was to disseminate the findings of the photovoice and perspective exchange activities, and invited participants to deliberate on the challenges and opportunities of addressing urban sustainability challenges identified through the research. The city workshop was held in Chattogram and brought together key policy and planning stakeholders, including the Mayor of Chattogram and the chief planner of Chittagong Development Authority. The national workshop was organised in Dhaka and involved national policy stakeholders, such as the national Minister of Planning and the Minister of Disaster Management and Relief, as well as UN organisations, civil society, and academia (see Table 2). Each workshop was also joined by three migrants who provided testimonies of their lived experiences of the city with the help of their photographs taken for the photovoice activity. The participation of migrants in the policy workshops was entirely voluntary and participants self-selected to attend these.

Responses