Characterizing the polycentricity in waste governance: a comparative study on Shanghai, Tokyo, and Hong Kong

Introduction

Urbanization, population expansion, and economic growth have contributed to the accumulation and proliferation of municipal solid waste (MSW)1,2,3. According to statistics, the generation of MSW will reach 3.4 billion tons in 2050—an increase of nearly 70% compared to 20104. However, despite the global concern over waste management, the majority of regions continue to rely on simplistic disposal methods. This mismanagement exacerbates the negative externalities associated with MSW, impacting the environment5,6,7, society8, and economy9. Consequently, it poses a significant threat to urban sustainability, leading to issues such as urban environmental degradation, public unrest, and more10,11. The need for effective MSW management has become paramount, as it has far-reaching implications on a global scale12. In response to the dilemma, the municipal authorities are also undertaking initiatives to counteract this dilemma in waste management by including technology, policies, and management modes13,14,15.

Originating from the discussion of common resource governance, Ostrom developed the polycentric governance theory from the market and government governance dichotomy, arguing that the governance based on multiple independent decision-making centers, coupled with institutional and policy arrangements, can resolve collective action dilemmas and achieve satisfactory performance16,17,18. Focusing on waste governance practices, it is found that government or market governance cannot be effective in all contexts, and the monocentric governance mode often induces different types of failures19. With involving more stakeholders at the community level from the life cycle perspective of the management process20, the effectiveness of waste governance is becoming increasingly prominent under the synergy of various independent decision-making centers21. In difference to other governance approaches’ core thrusts, the governance structure behind it shows a remarkable polycentricity19 and varies from city to city. Therefore, this paper applies to explore the following research question: at the community level, what are the differences observed in the polycentric waste governance modes across different cities?

There have been some attempts to spotlight the current literature, but the recent works about waste governance mode are mostly grounded on specific-case modeling22,23,24 and its environmental impact assessment25. Therefore, it is challenging to characterize polycentric waste governance for different regions, although current work has systematically compiled the methods for evaluating the circular economy26. As of now, the relative absence of comparative studies on waste governance27, weakens the broadening of waste governance knowledge. There are some articles that try to evaluate waste governance performance by developing respective indicator systems28,29,30. However, these concepts center on overall system assessment only, which demands the provision of feasible measures, especially the measures developed from stakeholders’ perspective, for the improvement of waste governance practices.

Beyond the assumptions of complete rationality and information of traditional game theory, evolutionary game theory is a useful approach to depict the equilibrium strategies of multiple stakeholders within the system by providing the dynamic evolutionary process31, which has been widely applied to the analysis of complex multi-actors system, including the waste management systems19,32,33. In the polycentric waste governance system, each governance agent will make a decision based on the premise of economic rationality due to the economic attributes of waste, which means that the strategy with higher economic benefits will be selected. Moreover, driven by economic interests, there is potential competition among various governance actors, such as the competition between formal recyclers and informal recyclers. With the influence of waste flow, economic value, and external policy intervention, etc., the decision-making of each agent in the polycentric waste governance system will exhibit a dynamic equilibrium, which is applicable to employing the evolutionary game theory.

Therefore, rooted in the current governance landscape in various cities, this paper aims to develop agent-based modeling by considering the interactions and evolution of the decision-making among different stakeholders. Drawing on previous modeling analysis19, the game theory approach is, furthermore, employed to examine the polycentricity of urban waste governance in various cities. Combined with the collected data and the mathematic analysis, the proposed model will produce the equilibrium strategy combinations of the stakeholders, denoting the operational mode in the polycentric waste governance, which can characterize the polycentric waste governance in various cities. This study focuses on three megacities–Shanghai, Tokyo, and Hong Kong, to measure the polycentricity of waste governance. It aims to identify the differences between these cities, understand the underlying reasons for the heterogeneous results of polycentricity, and evaluate the impacts of different polycentric governance patterns on urban sustainability. The research findings are expected to enrich the knowledge about polycentric waste governance in various developing contexts while providing decision support for the policy-makers in other regions to facilitate the implementation of waste governance work.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the model for characterizing polycentric waste governance, followed by the introduction of various characteristics in different cities. And then, the third section delves into the underlying factors that contribute to these differences, explores the heterogenous impact of various polycentric governance modes on urban sustainability, and proposes potential pathways and recommendations to facilitate polycentric waste governance in different contexts. For detailed information on the modeling process and data sources utilized in this analysis, please refer to the Methods section.

Results

The model depicts the polycentricity of waste governance

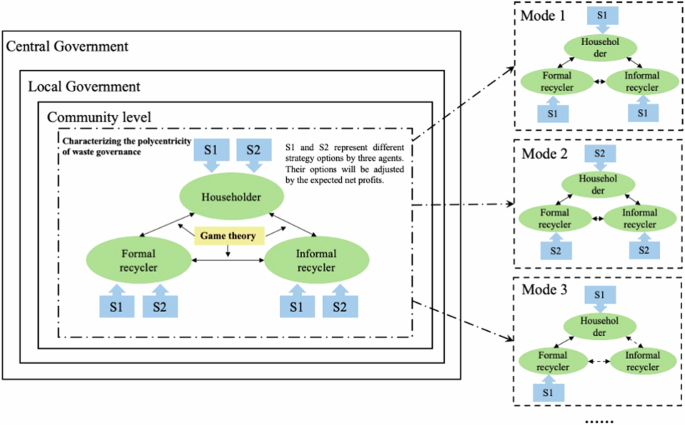

As presented in Fig. 1, this paper focuses on characterizing polycentric waste governance at the community level. Considering the actors involved in the polycentric governance, this paper incorporates the tripartite subjects—the household, formal recycler, and informal recycler as the main stakeholders to be analyzed from the perspective of inclusive waste management. The game modeling-based approach is applied to investigate the different polycentric characteristics based on the waste management activities of various cities, and a tripartite game model is constructed. The three main stakeholders are assumed to operate in line with bounded rationality. In that sense, they will conduct strategic adjustments according to the expected returns under different strategies (S1 and S2 represent the different strategies adopted by the three subjects) and eventually stabilize the equilibrium state of the strategy combination. The equilibrium strategies chosen by these stakeholders denote the operational modes of waste governance in different cities, then characterizing the heterogenous polycentric waste governance structures.

The model aims to measure the polycentricity of waste governance at the community level, where the key players include households, former recyclers, and informal recyclers. The three will rely on the expected net profits under different strategies to make decisions, thereby arriving at the equilibrium of strategy combination. Here, S1 and S2 represent the positive and negative strategy choices of these agents, respectively, and modes 1, 2, and 3 denote the waste governance modes in different cities.

Based on the problem description and basic parameter assumptions, we calculate the expected benefits of different subjects under various strategic interactions in the polycentric governance structure. Furthermore, using the payoff matrix, we calculate the replicated dynamic equations of the corresponding game players (see “Methods” section). Combined with previous studies34,35, we leverage the Jacobian matrix to distinguish the potential Evolutionary Stable Strategy (ESS) from eight pure strategy equilibrium points and the corresponding equilibrium conditions, as shown in Table 1.

Heterogeneous waste governance features in three megacities

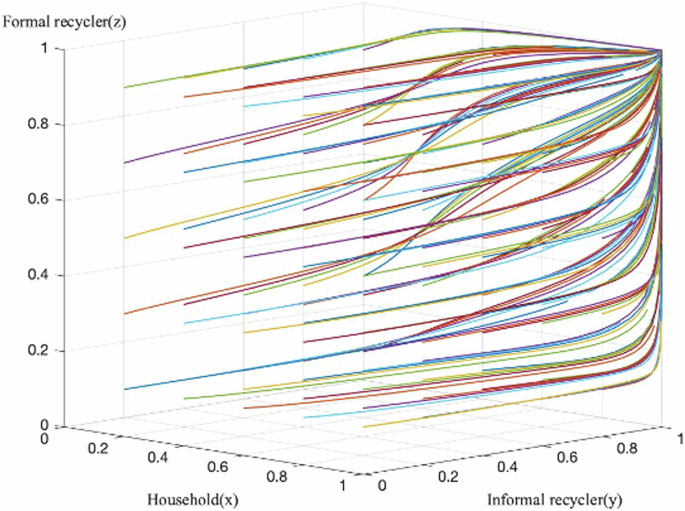

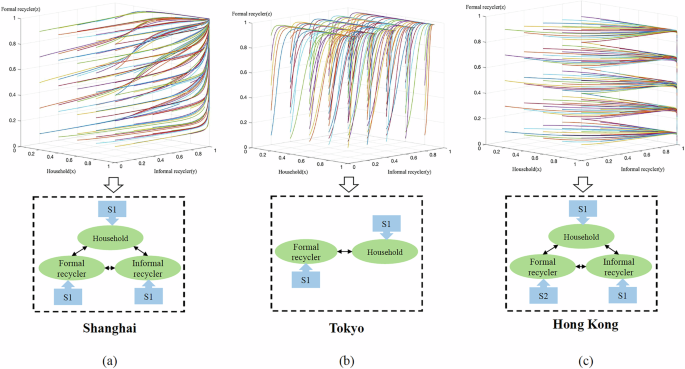

Based on the data collection (See Methods) and the game model proposed in this paper, we employ MATLAB 2018a to describe polycentric features in different cities—Shanghai, Tokyo, and Hong Kong—by drawing the evolutionary trajectory to ESS. The value of the parameters and corresponding data sources are explained in Supplementary information B. The following graphs indicate the divergent polycentric characteristics in different urban waste governance scenarios.

The Shanghai case

The trajectory of evolving to ESS in the polycentric waste governance model has been drawn based on the data collection in Shanghai. To be specific, MATLAB 2018a has been employed to do the analysis. The values of (x), (y), and (z) are initialized from 0.1 to 1, denoting the probabilities of choosing the positive strategy by three stakeholders. The evolutionary step is set as 0.2; each line with a different color represents the evolutionary trajectory of various initial points. And the equilibrium state characterizes the polycentric waste governance. Here, Fig. 2 presents the result of taking Shanghai as the instance.

In Shanghai, regardless of the initial intentions of the households, informal recyclers, and formal recyclers, the final equilibrium indicates that all three will stabilize at (1, 1, 1), which means that they will choose an active strategy in polycentric waste governance work. Therefore, the polycentric waste governance in Shanghai is characterized by the participation of households, informal recyclers, and formal recyclers, all of whom adopt a positive strategy.

The result reveals that the equilibrium state of strategy choices for the three stakeholders is represented by (1,1,1), indicating that all three agents would adopt positive strategies to facilitate the MSW management work in Shanghai. This means that the households will engage in waste classification with the help of formal recyclers, and the informal will choose to cooperate with the formal recyclers in the MSW management system. In line with the practice, the successful implementation of the mandatory waste separation policy in 2019 has resulted in more households’ engagement in waste governance with 99.5% accuracy for sorting the food waste, contributing to increase of the recyclables by 114.5%36,37,38. To address the negative environmental impact caused by profit-oriented practices of informal recyclers, authorities have implemented stringent measures to regulate such behaviors and mitigate ecological challenges. Moreover, efforts have been made to foster collaboration between the informal and formal sectors, such as integrating the MSW recycling network with the resource-reutilization network39. This ensures that waste collected by informal recyclers is disposed of in a certified manner. At the same time, the formal sector actively engages at the community level by providing convenience to reduce the time cost of sorting for households39. Also, the incentive measures undertaken by the formal sector, including economic incentives and enhancing public awareness, are introduced to motivate households to participate in the governance work40,41,42. For instance, the residents accurately finish the sorting work according to the regulations, and they actively engage in the waste management policy design.

Currently, Shanghai’s waste management has already formed a polycentric governance structure with households, informal recyclers, and formal recyclers aiming to build a zero-waste city with harmless disposal, waste reduction, and resource reutilization. Based on Shanghai’s example, the waste sorting policy has been subsequently disseminated to other cities in China, such as Beijing, Nanjing, etc43,44, with various business models at the community level45.

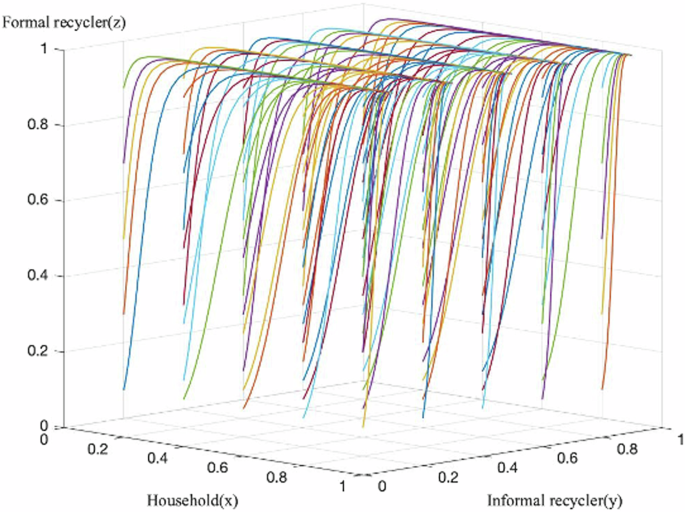

The Tokyo case

When considering the case of Tokyo under the same settings, as shown in Fig. 3, it is found that the equilibrium state of behavioral evolution among the governance actors is diverse—(1, 0.1, 1), (1, 0.3, 1), (1, 0.5, 1), (1, 0.7, 1), and (1, 0.9, 1), indicating that both formal recyclers and households eventually choose positive strategies within the MSW management system with the absence of informal recyclers. For example, the households will accurately sort the waste, and the recyclers will fully engage in the waste recycling and transfer. However, the informal recycler’s willingness to participate is only influenced by the initial value, and their choices do not impact the strategies of other stakeholders, and vice versa. Therefore, in Tokyo, the informal sector is rarely detected in the waste governance system. In comparison to the other two actors, the informal recycler plays a relatively insignificant role in the MSW management system.

Spotlighting the case of Tokyo, it is detected that the equilibrium state presents a diversity with (1,0.1, 1), (1, 0.3, 1), (1, 0.5, 1), (1, 0.7, 1), and (1, 0.9, 1), which suggests that both households and formal recyclers will actively participate in waste governance. The intention of informal recyclers, however, is determined by the initial state. In other words, the polycentric waste governance pattern in Tokyo is featured with the dominance of only two subjects with positive strategy—households and formal recyclers—while the informal recycler is not a pivotal governance actor.

Since the initiative of constructing a sound material-cycle society, proposed in 2000, the Japanese government has established a top-down waste management scheme, based on the 3 R principle (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle), and emphasized the bottom-up participation of community-level actors in waste governance46. For example, community meetings and events are conducted by the authorities to provide helpful information on waste separation rules47. At the same time, the environmental awareness of households and consideration for others creates intense community supervision, and such community-level mutual supervision allows citizens to participate actively in waste governance. Meanwhile, financial penalties have also been imposed by the government for non-compliance behaviors. Thus, effective diffusion of public policy is achieved from the policy-makers to the households. Based on the active participation of households, the government authorized formal recyclers to engage in waste transfer and disposal, with subsidies and contracts to stimulate their active participation. Meanwhile, the authority adopted corresponding regulatory instruments—the sound institutional framework (e.g., take-back policy), strict regulatory measures, a solid foundation of resident awareness, and stringent penalties for non-environmental behavior, resulting in the exclusion of the informal recyclers48,49,50. Consequently, there is not enough space for informal recyclers to operate in the waste governance system. Therefore, Tokyo’s polycentric governance structure is dominated by households and formal recyclers.

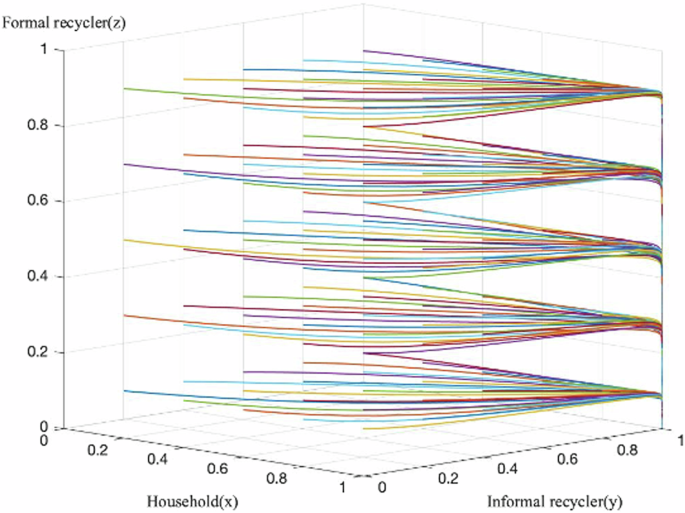

The Hong Kong case

Based on the findings presented in Fig. 4, it is evident that in Hong Kong, despite the initial variations, the equilibrium strategy combination of behavioral evolution among governance agents eventually reaches a stable state of (1, 1, 0), implying that only households and informal recyclers are willing to take positive strategies in Hong Kong. As found in our observation, it implies that households will actively participate in the polycentric waste governance system, while informal recyclers prefer to collaborate with formal recyclers in a cooperative strategy to promote waste governance. However, the lack of sufficient financial support from the government hinders sustainable improvements in the formal sector. Consequently, formal recyclers only provide limited contributions, and they are not motivated to invest more in motivating households or upgrading recycling infrastructure due to the lower expected profits51.

Unlike Shanghai and Tokyo, the results for Hong Kong reveal that the strategic combination of the three subjects will reach a steady state at (1, 1, 0). This implies that the polycentric waste governance in Hong Kong also includes the tripartite subjects of the households, formal recyclers, and informal recyclers. However, only the household and informal sector are actively involved with limited contributions by the formal recycler.

Most households in Hong Kong are aware of environmental protection and valid cognition of waste separation and recycling. In addition, the forthcoming implementation of a charging policy for MSW has reinforced households’ understanding of waste management so that most Hong Kong citizens tend to engage positively in the polycentric waste management system52,53. In terms of recycling agents, Hong Kong’s recycling system is characterized by a symbiosis of informal and formal recyclers54. Informal recyclers are inclined to adopt a cooperative strategy with formal sectors due to the stringent penalties imposed by enforcement authorities on environment-friendly activities. However, given the excessive financial burdens and the lack of subsidies, formal recyclers tend to maintain the current options, resulting in the absence of continuous improvement to the recycling infrastructure, community engagement, and other aspects. Although the charging policy of MSW may alleviate the side-effects of the non-positive strategy of the formal sectors, a lack of perceived economic incentives by the formal recyclers may cause the malfunctioning of waste governance in some areas, such as the Kowloon West in Hong Kong, where the environmental awareness of the households needs to be improved52. Overall, the polycentric waste governance in the Hong Kong region is featured by the active participation of households and informal recyclers, while formal sectors choose to participate reactively.

Discussion

As presented in Fig. 5, different polycentric waste governance structures are detected in three megacities. Specifically, the results suggest that waste governance in Shanghai is currently represented by the active participation of households, informal recyclers, and formal recyclers. However, in Tokyo, only two principal players are observed in the polycentric waste governance system, which are households and formal recyclers. The informal recyclers are excluded. In contrast, in Hong Kong, three stakeholders are engaged—households and informal recyclers are fully involved, while formal recyclers provide limited contributions to the waste governance work.

a Shows that the polycentricity of Shanghai’s waste governance is featured by the positive strategies of the three stakeholders. b represents the two main players—formal recyclers and households—engaged in waste governance work with a positive strategy. c denotes that informal recyclers and households opt for a positive strategy in Hong Kong’s waste governance, while formal recyclers provide limited contributions with a negative strategy.

On the one hand, the polycentric features of waste governance are characterized by divergent governance modes—for example, the disparity between Hong Kong and the other two cities. To be specific, in Hong Kong, a market-oriented governance mode is employed. This approach relies on market-based trading to support the operations and growth of companies, although some government funding is provided during the initial stages for formal recyclers. However, the high transaction costs of some waste, coupled with limited economic benefits, discourage formal recyclers from undertaking infrastructure renewal, scaling up their operations, etc. As a result, the current waste governance system in Hong Kong faces significant challenges as waste continues to increase. In contrast, a hybrid of market-oriented and government-led governance is implemented in Tokyo and Shanghai. For instance, in Tokyo, the government provides top-down policy formulation that regulates the behavior of households and informal recyclers on the legislative level55,56. Yet in a parallel dynamic, a market-driven approach is simultaneously coordinating the bottom-up waste governance work by providing sufficient profit margins and facilitating the sustainable improvement of waste management57. Similarly, in Shanghai, the government is committed to collaborating with market forces to promote waste management58. Since the implementation of the mandatory waste classification policy in Shanghai in 2019, households have become another vital subject in the waste governance system. The households’ efforts to separate waste at the source allow the effective operation of the governance mode.

On the other hand, different socioeconomic factors and policy designs have given rise to diverse polycentric features, especially in the role of informal recyclers in the governance system. In Tokyo, informal recycling is rarely observed, and its significance within the governance system is minimal due to the ingrained habits of residents and strict regulations. Through extensive education efforts, Tokyo’s residents have developed strong behavioral motivations toward resource conservation and environmental protection, leading to pro-environmental behaviors and practices such as sophisticated waste sorting. These widespread behavioral habits have become social norms that guide and regulate residents’ actions, facilitating the transfer from waste generation to waste recycling. The informal sector is thus virtually non-existent in Tokyo. In contrast, public education in other cities has yet to instill eco-friendly behaviors in residents. In the absence of a stringent regulatory framework and substantial behavioral change among residents, informal recyclers continue to play a significant role in the global recycling market, even in affluent regions such as Hong Kong54,59,60. The substantial wealth disparity in Hong Kong has forced some elderly individuals to participate in the waste governance system as informal recyclers. Similarly, the informal sector in Shanghai is a key player in the market that cannot be ignored. Following the waste recycling revolution in 2019, policy constraints, such as penalties for non-environmentally friendly behaviors, have transformed the relationship between informal recyclers and formal recyclers from competitive to collaborative, with a growing inclination towards formalization among informal recyclers61,62,63.

Different polycentric governance structures in the three cities showed diverse effects on the economic aspects of the recycling chain. In Shanghai, residents’ positive behavior, such as precise sorting, also reduces the cost of recyclers at the source. In return, formal recyclers also provide positive incentives to collect the waste generated by the households. In addition, the collaboration between informal recyclers and the formal sector further contributes to the economies of scale in the recycling market. In Tokyo, despite the absence of informal recyclers, the intrinsic motivation of citizens enables the waste stream to flow effectively in the sound material-cycle society. Until now, the output of Japan’s circular economy has reached 50 trillion Yen64. In contrast, in Hong Kong, the slack actions by the formal recycler result in most of the waste flowing into the informal sector54,65. The informal-led waste governance mode is struggling to yield economic scale benefits, with Hong Kong’s urban environmental industry accounting for only 0.4% of the total GDP in 201865.

The polycentric governance mode in Tokyo, led by residents and formal recyclers, has increased the social recognition of the participants involved while reducing the social discrimination against the practitioners through well-organized social and public education. However, with the absence of informal, this pattern may have adverse effects on low-income groups during the inclusive social transformation. Low-income groups are primarily involved in informal recycling. For example, in Hong Kong, older individuals, who are vulnerable to external risks and uncertainties, predominantly engage in informal recycling work. The marginalization of the informal may entail more social displacement due to few job opportunities66, exacerbating the challenges faced by the low-income groups in escaping extreme poverty. Consequently, modes of governance (such as those observed in Shanghai and Hong Kong) that integrate the informal sector as one of the main actors remain crucial in safeguarding vulnerable groups.

The waste governance modes implemented under the three polycentric structures have led to improvements in ecological benefits. Effective waste recycling and disposal help mitigate negative environmental externalities such as waste-carbon emissions and pollutant reduction1. However, the involvement of informal players in waste governance in Shanghai and Hong Kong poses challenges to environmental protection compared to the formal recyclers in Tokyo, who are responsible for the entire transfer and disposal chain, such as the secondary pollution that occurs in the collection and preprocessing stage. Despite the implementation of strict regulations, the flexibility and mobility of the informal sector allow for non-environmentally friendly practices, which jeopardize the environment and the health of workers61.

To summarize, Tokyo’s waste polycentric governance mode, dominated by residents and formal recyclers, has positive effects in terms of economic growth, social recognition, and environmental protection. Yet, when this mode is disseminated to developing countries, the exclusion of the informal sector may lead to the loss of social inclusion for low-income groups. In contrast, the polycentric waste governance in Shanghai and Hong Kong exhibits greater inclusiveness towards informal recyclers. However, the potential environmental risks in the informal sector in the two cities require the local authority to adopt appropriate countermeasures, such as digitalization of the whole process of waste management, innovative business models, etc. In addition, compared with Shanghai and Tokyo, Hong Kong’s polycentric waste governance mode has not yet leveraged the economic potential in the waste management chain, highlighting the need for careful consideration of the mechanism design for the coordination of participating entities to promote the development of the circular economy.

Waste is a post-consumer product with negative environmental externalities. Despite the identification of economic potential in the waste recycling and reutilization market, a market-oriented governance mode is prone to failures due to varying profitability across different waste categories—for example, failure under market mechanisms67,68. Therefore, regarding the polycentric waste governance in other cities, in line with previous discussions69,70, it is advocated that the alliance-based governance embracing various stakeholders should be taken into account to mitigate the potential market failure. In addition, efforts driven by households at the community level also facilitate waste management at its source71. Confronting diverse urban contexts, it is recommended to regulate and stimulate household behavior at the micro level and foster collaborative governance between the government and the market. This includes the cultivation of households’ behavior habits42 and the provision of policy support by the administration sector, such as subsidy policies72, to facilitate market-oriented operations.

Importantly, with 80% of the world still developing and a third of the population living in extreme poverty, informal recyclers cannot be overlooked despite the potential environmental risks associated with their activities. Therefore, towards inclusive waste management, the policymakers, especially in developing regions, should take some initiatives—the digitalization of management processes, business model innovation, policy innovation regarding the collaboration between informal and formal sector, etc., to engage them in the governance system while alleviating the negative externalities by informal recyclers’ behavior, aligning with the UN’s goal of leaving no one behind.

The escalating issue of waste accumulation with its adverse environmental impacts has become a global concern in the realm of urban sustainability. To tackle this problem, cities have launched various initiatives, leading to diverse outcomes in waste governance. Drawing on game theory, this paper presents a model to characterize the polycentricity of waste governance across diverse cities from the perspective of governance agents. Notably, the findings reveal that polycentric waste governance in Shanghai exhibits a collaborative effort involving households, formal recyclers, and informal recyclers. In contrast, waste governance in Tokyo is predominantly driven by formal recyclers and households. Hong Kong’s waste governance presents the feature where formal recyclers provide limited contributions to waste governance while households and informal recyclers adopt a proactive strategy. Behind these, the heterogenous governance modes, socioeconomic factors, and policy designs shape different polycentric characteristics. In relation to the triple bottom line of sustainability theory, the polycentric waste governance in Tokyo and Shanghai contributes to the expansion of the circular economy, while Hong Kong’s potential in this regard remains underestimated. Although the modeled by formal recyclers and citizens improves social recognition in Tokyo’s context, this mode’s dissemination will offer limited inclusion to low-income groups, especially in developing regions. In this case, the polycentric waste governance in Shanghai and Hong Kong provides a more inclusive approach to the informal sector. However, it is imperative for authorities in Shanghai and Hong Kong to regulate informal behavior to alleviate the potential environmental risks. The model proposed in this paper establishes a foundation for characterizing waste governance and analyzing the inherent decision-making mechanism of governance agents in megacities. This model, coupled with the data from other cities, will provide more interesting findings regarding waste governance to enhance the integration and sharing of waste governance knowledge. Also, the insights gleaned from this study can serve as a valuable reference for the policymaking of MSW management in developing countries, such as the choice of governance mode, mechanism design of government-market collaboration, inclusion, and regulation of the informal sector, etc., thereby facilitating the pursuit of urban sustainability.

Future studies can be conducted from the following aspects. First, this study has not extensively examined the influence of different MSW fractions on the polycentric waste governance pattern. However, it is important to note that the MSW component will directly affect MSW’s economic attributes in the recycling market, potentially leading to heterogeneous governance patterns. Therefore, investigating how variations in MSW components affect the waste governance pattern holds promise for future research. Second, in terms of modeling expansion, it would be beneficial to incorporate a complex network approach to refine the scope of this study further. This could involve considering the heterogeneity within households and exploring the interconnections among different stakeholders. This enhanced model would provide a more comprehensive understanding of waste governance. Besides, this paper is a community-level-based modeling work. Therefore, more governance agents, for example, the government, could be engaged in this analytical model to characterize the polycentric waste governance more accurately at a broader level, which requires a reflection on how to define this agent’s payoff by comprehensively considering the benefits in economic and non-economic dimension. Also, in the polycentric waste governance model, how does the feedback from the community level influence the government’s policy formulation and adjustment is interesting in future model extension. And the model is expected to be developed and verified by involving more actual scenarios. Third, a more interesting analysis may be conducted by considering various strategies set with the advancing technology and policies—the digitalization transition, prevailing environmental awareness, social inclusion, etc.

Methods

Evolutionary game modeling

Problem description

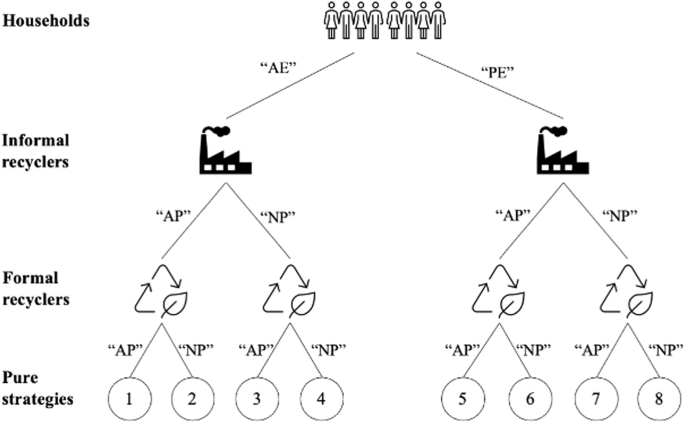

-

(1)

Three players and their strategy sets: This method incorporates three principal actors—households, informal recyclers, and formal recyclers—in the polycentric waste governance model toward an inclusive circular economy. Their strategy sets include two different strategy options, as displayed in Fig. 6. Specifically, the households’ active participation indicates that they will engage in the waste governance work as per the relevant regulations—engaging the recycling system as a self-organization, co-designing the waste management policies, etc. In this case, the generated waste will be separated and recycled accurately. Alternatively, the opposite strategy option represents that households will contribute to the waste governance work with less effort. Consequently, only part of the waste is sorted and recycled effectively. Thus, the strategy set for households is ‘Active Engagement’ and ‘Partial Engagement’, namely ‘AE’ and ‘PE’. The strategy sets for the informal and formal sectors include ‘Active Participation’ and ‘Negative Participation’, namely ‘AP’ and ‘NP’. The informal recyclers’ ‘AP’ suggests that they will be involved in a cooperative strategy with the formal sector, and the waste collected by the informal recycler will be transferred to a certificated sector and disposed of by legitimate treatments. On the contrary, adopting a negative option by the informal recyclers implies that they will compete with the formal sector in the market. The collected waste will also be diverted to the informal channels for subsequent processing and remanufacturing. Regarding the formal sector, this actor taking ‘AP’ presents that they will undertake proactive measures to stimulate the engagement of other stakeholders, such as the construction of recycling infrastructure, bonuses for households, etc. Conversely, in this paper, limited contribution to promoting waste governance is considered as the formal sectors’ ‘NP’ in the polycentric waste governance model. Besides, although the government is not involved as the principal player due to the economic rationality hypothesis, its influence has been considered as an external intervention to influence these agents’ expected profits.

Fig. 6: Game tree model.

Focusing on the polycentric waste governance at community level, three main agents—households, informal recyclers and formal recycler, are involved. Three players have two different strategy choices, which are determined by the expected profits. Strategies 1-8 represent eight pure strategies in the tripartite game model. This figure only represents the involved governance agents and their strategy sets, and the order presented does not indicate the hierarchical governance structure.

-

(2)

Cost: The differentiated strategy choices of the three stakeholders undertake different costs. Taking the household as an instance, they have to spend the time costs and learning costs with the choice of ‘AE’. Here, the cost per unit is recorded as ({c}_{1}). Meanwhile, the formal sector with ‘AP’ will reduce the potential costs incurred by the household with an external convenience like intelligent sorting machine, workers’ guidance, etc. The reduced cost per unit is, therefore, denoted by ({c}_{0}). If the household adopts ‘PE’, the potential loss, including the penalty from the community and regulatory authorities, will happen. We take ({c}_{2}) to represent the unit loss by the households in this case. Focusing on the informal recycler, they would pay for collecting the waste from the households in the market trading, and the unit price covered by the informal recycler is recorded as ({p}_{1}). Besides, when the informal sector opts for ‘AP’, this sector will invest more in the collecting process to enable environment-friendly collecting and transportation, such as adopting green recycling equipment and technology, and the unit cost in this stage is represented as ({c}_{R}). Similarly, the formal sector’s ‘AP’ would also mitigate the cost of collecting and transportation for the informal recycler. The reduced part is denoted by ({c}_{0}^{{prime} }). However, when the informal recycler determines to compete with the formal sector, that is ‘NP’, the cost of collection and transportation is ({c}_{R}^{{prime} }). Due to the absence of strict eco-friendly requirements, we assume that ({c}_{R} > {c}_{R}^{{prime} }). Similar to the case mentioned before, the informal sector will be the free-rider and benefit from a cost reduction, when the formal recycler takes ‘AP’. In this case, the reduced cost is also denoted by ({c}_{0}^{{prime} }). The potential environmental negative externalities from the informal sector’s ‘NP’ will also be penalized by the supervision sector. Hence, the penalty is represented as ({aL}), where (a) implies the intensity of regulation enforcement and (L) is the financial punishment per unit. In addition, the negative spillover effects entailed by the informal disposal will jeopardize the workers’ health. The potential unit loss is marked as ({{c}}_{h}). In terms of the formal sector, the operating cost is denoted as (C). Here, the unit price of waste paid by the formal sector to households is recorded as ({p}_{2}). Further, we assume collection costs per unit afforded by the formal recycler with different strategies are equal, which is represented by ({c}_{3}). However, if the formal recycler opts for ‘AP’, the extra total cost,({C}_{e},) will be afforded. Moreover, when the informal recycler takes the positive strategy, they will transfer the collected waste to the formal sector and benefit from the process. Thus, the recycling price paid by the formal sector to the informal recycler is recorded as ({p}_{3}).

-

(3)

Benefits: According to the narratives about the expenses of different stakeholders, two sources of benefits are detected for the households. The benefits from the informal and formal channels are denoted as ({p}_{1}) and ({p}_{2}), respectively. Besides, the ‘AE’ of the households will be appreciated by the community with a unit bonus of ({Y}_{1}), such as accurately sorting all types of waste. The revenue earned by the informal recyclers are derived from selling the collected waste to the downstream sectors. Therefore, the unit revenues of choosing ‘AP’ and ‘NP’ are severally denoted as ({p}_{3}) and ({p}_{4}). Additionally, the potential resource attributes of waste will yield economic values for the formal recycler. Here, ({p}_{5}) is adopted to represent the unit revenue of the formal recycler. Due to the profitability of the supply chain, we assume ({{p}_{5} > {p}_{4},p}_{3} > {p}_{1}+{c}_{R},{{p}}_{2}+{c}_{R}). Meanwhile, at the operation stage, the government would subsidize the formal recyclers to encourage their positive participation in recycling the waste, and the unit subsidy is marked as (S).

-

(4)

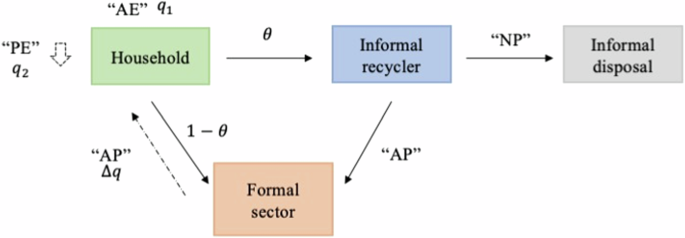

Waste generation and flows: As shown in Fig. 7, household’s ‘AE’ implies that they will sort the generated waste properly, and in this case, the amount of collected waste is denoted as ({q}_{1}). While in the case of ‘PE’, considered by the household, we use ({q}_{2}) to represent the quantity. In the meantime, the formal sector with ‘AP’ inspires the households’ participation with an increased amount((triangle q)) of collected waste. Therefore, the total amount of collected waste in this case is ({q}_{2}+triangle q). Here, we assume ({q}_{1}, > ,{q}_{2}+triangle q). Besides, the proportion of waste volume flowing into the informal recycler is recorded as (theta in (mathrm{0,1})). Correspondingly, the percentage covered by the formal sector is (1-theta). Hence, when the household chooses ‘AE’, the waste streams to the informal and formal sectors are marked as (theta {q}_{1}) and (1-(theta))({q}_{1}), respectively. If the household decides to participate negatively and the formal sector takes a positive strategy, the waste flows to informal and formal channels are denoted as (theta ({q}_{2}+triangle q)) and ((1-theta )({q}_{2}+triangle q)), respectively. Accordingly, the waste collected in two different ways is recorded as (theta {q}_{2}) and (1-(theta))({q}_{2}), when the household chooses to negatively engage in waste governance.

Fig. 7: Waste flow chart.

In general, waste is generated by the household and recycled by the informal recycler as well as the formal recycler in different proportions. Depending on the choice of informal recycler’s strategy, the waste flows to various disposal channels, e.g., under an active strategy, it goes to formal disposal. Otherwise, it flows to the informal. In addition, the strategy choices of the household and formal recyclers also cause the fluctuation of waste generation. For example, the households’ active participation in waste sorting activities affects the initial amount of waste generated, and the incentives from formal recyclers also influence the amount of recycled waste when the household opts for ‘PE’.

-

(5)

Probability: The three agents in this model are assumed to adhere to bounded rationality. They also have the discretion to determine their strategy choices based on their expected profits from various strategies. Here, the probabilities of adopting a positive strategy by three agents are assumed as (x,y,zin (mathrm{0,1})). Accordingly, the possibilities of choosing the negative strategy are denoted by (1-x,1-y,1-z).

Payoff matrix

Based on the modeling description and basic assumption, the payoff matrices of these actors in the polycentric waste governance model are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Replicator dynamic equations

According to the expected profits with different strategies in payoff matrices, we have calculated the replicator dynamics equations(See Supplementary information A), which are displayed in Eqs. (1)–(3).

ESS analysis

Based on the Jacobian matrix (See Supplementary information A), the first Lyapunov method and Ritzberger and Weibull’s research findings31,32, the stability of eight pure strategy equilibrium points is analyzed, as displayed in Table 4.

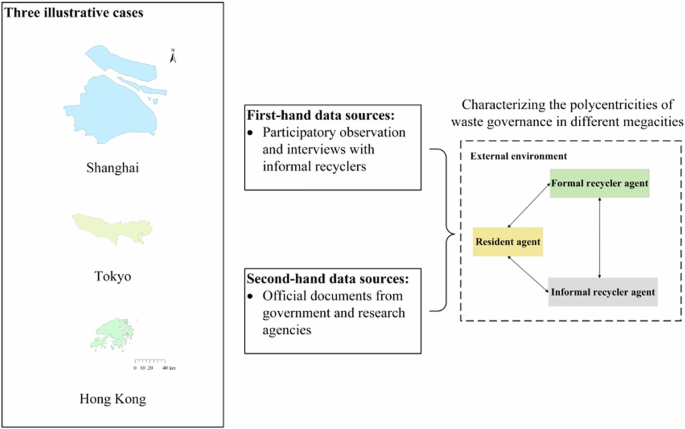

Case studies

To unravel the intricacies of polycentric waste governance, we selected three representative cases—Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Tokyo, as focal points for our investigation. These megacities have embraced waste policy interventions to foster waste governance but in different stages. Thus, it will allow us to explore the variety of governance structures and examine the factors underpinning the divergent waste governance. Our study adopted a comprehensive approach to collecting the data and encompassing the official documents from key government departments and research agencies, about waste management. To augment the information obtained from second-hand data sources, we conducted extensive on-site investigations and surveys at informal recycling stations in Shanghai and Hong Kong. We investigated 7 recycling points covering five districts in Shanghai and 7 recycling points covering six districts in Hong Kong, mainly in the form of participatory observation and interviews. The questions inquired focused on the informal sector, e.g., the recycling prices of informal recyclers, the operating costs of informal recyclers, transportation costs, the revenues of informal recyclers, etc. (See Supplementary information C for details). Based on the first-hand data collection and the second-hand data collection, we assessed the institutional strengths or effectiveness of waste management policies, the voluntary participation of residents in waste separation and recycling, and the actual trades of recyclable wastes. We recorded the details of the general operation of the community-level waste management facilities, covering the aspects of waste collection, transportation, and processing. Subsequently, we extracted the waste collection and transaction structures and defined the attributes and parameters of each agent and their initial values. A schematic diagram is presented in Fig. 8 to specify the case study methodology.

We selected Shanghai, Tokyo, and Hong Kong as the target cities and conducted data collection accordingly. The data collected in this paper derives from a twofold approach: second-hand data based on publicly available government documents and research reports, first-hand data based on on-site research and interviews. The polycentricity of waste governance in these megacities can then be measured with the proposed model.

Responses