Helmet material design for mitigating traumatic axonal injuries through AI-driven constitutive law enhancement

Introduction

Skiing is one of the most practiced outdoor activities, with an estimated 135 million people skiing globally each year1,2. Skiing is an accident-prone sport with an injury rate of 2.8 for 1000 skiers3. Among the different skiing accidents, head injuries account for 16 to 19% of all injuries4,5,6,7. In cases of severe accidents, traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) emerge as the primary cause for hospital admissions within the skiing community, ranging from mild concussions to severe traumatic axonal injuries (TAI)8,9. This is especially surprising as it coincides with an increasing fraction of skiers wearing helmets on the slope, passing from 0% to 93 % over the period ranging from 2000 till 201910,11. Furthermore, the rate of brain injuries has remained relatively stable at around 18% of all yearly ski injuries12. Researchers described the protective effect of helmets against skull fractures but found helmets did not significantly reduce occurrence of intracranial lesion13. Helmets’ efficacy against traumatic axonal injuries raises public health concerns, especially given the almost epidemic levels of these injuries and their associated mortality rates due to TAI14. Therefore, reconsideration of helmet design based on the ability to reduce the TBI incidence rate is an urgent task. In particular, the development of novel dissipative materials dedicated to mitigating TBI for a variety of ski accident scenarios should be considered.

The current situation regarding TBI might result from out-of-date standards regulating ski helmets15,16. Indeed, the current standards focus on mitigating the head’s linear acceleration without considering rotational acceleration, which is one of the leading causes of brain injuries17. Furthermore, the standards focus on a single linear impact at a given speed of 22.3 km/h, failing to evaluate the protective capabilities of the materials at lower and higher speeds.

New technologies have aimed to mitigate the risk of TBI through slip interfaces18,19 or collapsible structures20. These technologies performed significantly better than conventional helmets in reducing the head’s rotational acceleration following an impact and, therefore, reducing the risk of TBI21,22. However, the actual helmet performance depends on the conditions and locations of the impacts. This is especially true for slip interface-based helmets21,23.

One difficulty in designing a helmet is assessing its possible mitigating effects on TBI24. Rotational-based metrics such as Brain Injury Criteria (BrIC), Rotational Injury Criteria (RIC), or Rotational Velocity Change Index (RVCI) have been considered as possible external predictors of TBI25,26,27. However, due to the complex nature of brain injuries, no consensus has yet been reached on the most appropriate metric to use. Furthermore, it has been recognized that the leading cause of TBI is brain tissue deformation inducing axonal diffuse injuries following a rapid head rotation during a shock28,29. From these observations, tissue-level metrics based on brain stress/strain fields are considered more accurate in predicting brain injuries when compared to kinematics-based metrics30,31,32. Brain strain-based metrics are derived from biofidelic finite element models (FEM), providing relevant results but at a high computational cost33. Recent studies developed a relationship between the head’s angular kinematics and brain strain metrics based on FEM models34,35. These findings could facilitate the development of novel helmets by reducing the time required to answer different predictive questions. This approach would save considerable time in the design process of protective equipment, especially when used in conjugation with state-of-the-art mechanical injury risk threshold30,36.

Expanded polystyrene (EPS) foam is the primary material used in helmet liners for impact mitigation. However, EPS performs poorly against rotational acceleration as it was not designed for this purpose but for thermal insulation applications37. The limited protective capabilities of EPS foam in helmets motivate the design of materials that specifically decrease rotational acceleration following shocks at different impact speeds38. Combining FEM analysis and deep learning tools is a promising approach to drastically reduce the number of numerical and experimental tests for evaluating a helmet’s protective properties under many impact scenarios. Recently, deep learning tools have been applied to material science for optimizing material composition design or mechanical properties39,40,41. Beyond material science, deep learning is already extensively used in numerous fields of biomechanics to reduce the computational cost of resource-intensive tasks or optimization processes such as FEM42, musculoskeletal models43, image segmentation44, motion/gait analysis45, and signal processing of wearable sensors46. In the field of TBI, effort has been made to use a deep learning approach to rapidly evaluate brain injury metrics such as maximum principal strain (MPS)47 or Von Mises Stress48 directly from the head kinematics at the centre of gravity.

This study will use kinematic and brain strain-based metrics to determine the material properties of more effective head protective equipment for snow sports. In particular, we expect to optimize the protective performance of the helmet at different impact energy levels by designing the liner material to mitigate angular accelerations. The optimization was performed through the development of deep learning models. Specifically, the input to these models was the energy of impact along with the material properties of the helmet’s liner, and the output was the rotational acceleration and velocity. These outputs were used to evaluate the mitigation performance of the material properties.

Methods

Finite element simulation

The model used in our study was composed of a Hybrid III (III) Head and neck finite element model coupled with a protective pad (dimensions: 110 × 60 × 20 mm) extracted from the finite Element Model of 2016 Riddell Speed Classic, both distributed by the Biomechanics and Research, LLC (Biocore). The University of Virginia Center for Applied Biomechanics previously validated the HIII head and neck model49. The protective pad was composed of two parts, a comfort layer and the protective liner (see Supplementary Section 1 for more details).

We selected a jaw impact as a baseline for brain injury mitigation. It has been found that the mandibular region is the most vulnerable region to angular acceleration50. The study was focusing on the reduction of brain injury; therefore, the jaw region was selected for impaction in order to perform material optimization.

The finite element analysis was performed using a commercially available explicit solver (LS-DYNA, version R12.0). The pre-processing was performed in LS-PrePost (v4.7, LSTC, Livermore, CA, USA) and the post-processing was computed using the Python Library from LASSO GmbH and custom scripts to process the data were written in Python.

Constitutive material law

We selected the crushable foam material model (MAT_63) in LS-Dyna to simulate the behavior of the protective pad. This model is specifically designed for modeling crushable foam with optional damping and a tension cutoff feature. It exhibits fully elastic unloading and treats tension as elastic-perfectly-plastic up to the tension cutoff limit. The crushable foam model required the input of five parameters: density, Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, stress-strain curve, tensile stress cutoff, and damping coefficient (see Table 1). All the parameters were taken from the literature following the EPS foam properties except for the stress-strain curve51,52.

Finite element input data

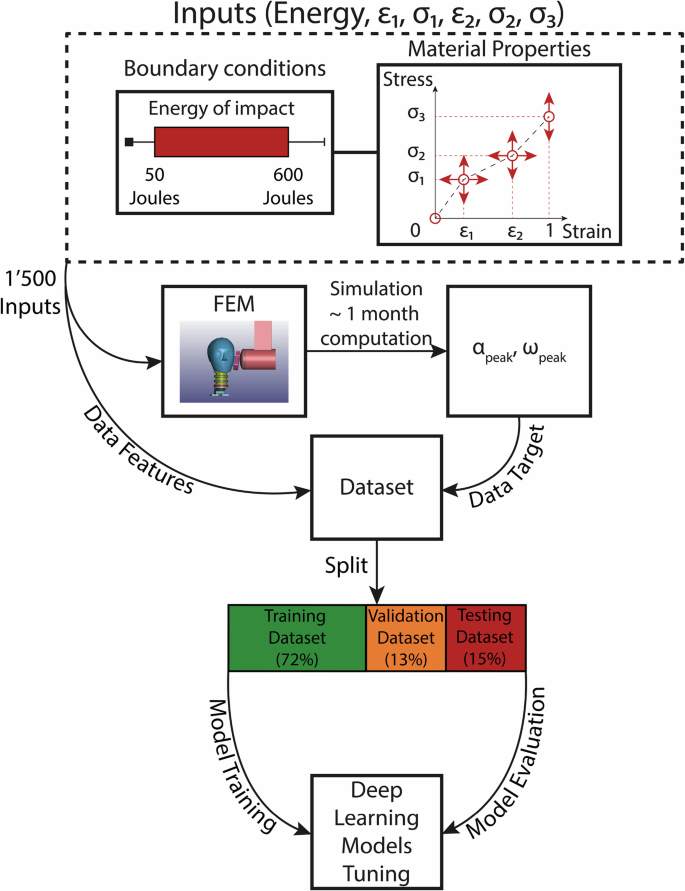

We generated 1500 different stress-strain curves for the pad material. We approximated these curves by four points, (ε0; σ0), (ε1; σ1), (ε2; σ2) and (ε3; σ3), for clarity see Fig. 1. To generate values of the four points, we used samples from distributions or constant values presented in Table 2. For the sampling, we used Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)53.

Two predictive models were developed: one for the peak in rotational acceleration and one for the peak rotational velocity.

Finite element output data

The finite element model computed the kinematic data (i.e., linear and rotational accelerations or velocity) of the headform at its center of gravity. We limited the study by considering the peak in rotational acceleration αpeak and the peak in rotational velocity ωpeak as these variables will be used in the brain injury metric. Based on αpeak and ωpeak, the maximum principal strain (MPS) and the maximum principal strain rate (MPSR) in the axial plane of the brain were calculated following Equ. 1 and 2 derived by Carlsen et al.34:

Our emphasis on the axial plane corresponds to the chosen impact scenario (Fig. 1), primarily inducing rotational motion along the x-axis and z-axis of the headform. We opted for the axial plane, which is the most sensible brain plane to both αpeak and ωpeak leading to higher values of MPS and MPSR.

Researchers underscored the significant role of maximal principal strain (MPS) and maximal principal strain rate (MPSR) as key predictors of traumatic axonal injury (TAI) risk Therefore, the predictions of ωpeak and αpeak for a set of stress-strain curves and energy levels enabled the evaluation of the resulting maximal principal strain (MPS) and maximal principal strain-rate (MPSR) in the brain according to Eqs. (1 and 2). For each input, we calculated the TAI risk according to Eq. 3 derived by Hajiaghamemar et al.36:

Deep learning datasets

The stress-strain curve and energy were the inputs, and the peak rotational velocity and acceleration of the head were the targets of the deep learning model. We used 85% of the 1500 FEM simulation data for training and the rest for testing the model.

Deep learning model optimization

We built the deep learning model with TensorFlow library (https://www.tensorflow.org/) of Python. Keras Tuner (https://keras.io/keras_tuner/) with 500 iterations optimized the hyperparameters of the model with Bayesian optimization (Table 3). This optimization’s objective was to minimize the mean absolute error of the model’s predictions. We optimized the hyperparameters of the deep learning model by using 15% of the training data as the validation data.

Results

Deep learning for material optimization

To assess the protective efficiency of helmet liners against brain injury during an impact, we performed numerical analyses using the available FE models for impact simulation and helmet assessment (Biocore LLC, Virginia). These simulations consisted of a pendulum impact test on a dummy headform (Hybrid III Head-Neck) covered by a single protective pad. The protective pad was extracted from the Riddell helmet FE model to reduce computational costs for training set preparation. By employing LS Dyna explicit solver (Ansys, Pennsylvania). 1500 simulations were processed at various impact energies and with different stress/strain curves for the pad material. The rotational kinematic data of the headform center of gravity were the model outputs, summarizing the approach by: f(Energy, ε1, σ1, ε2, σ2, σ3) = αpeak and g(Energy, ε1, σ1, ε2, σ2, σ3) = ωpeak. The resulting dataset was the cornerstone for building the deep learning models, as shown in Fig. 1, which summarizes the approach from the data generation using the FE simulation until the training and evaluation of the deep learning model.

Optimized deep learning models

The optimized hyperparameters for the two deep learning models predicting the peaks rotational velocity (ωpeak) and rotational acceleration (αpeak), respectively, are listed in the Table 4.

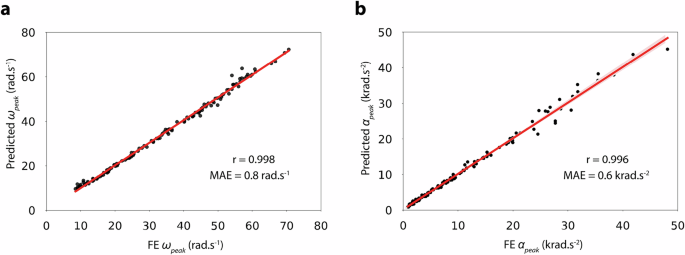

Table 5 displays the performances of the two models predicting ωpeak and αpeak. Both models showed a strong correlation according to Pearson’s correlation coefficient, reaching 0.99 as test score. At the same time, the mean absolute error of the deep learning models reached low values with the testing dataset: 0.79 rad.s−1 for ωpeak and 559 krad.s−2 for αpeak, representing 4% and 16% of the 1st quartile, respectively. Figure 2 illustrates the performance of the models using the testing dataset by plotting the predicted values of ωpeak and αpeak as of function of the values computed by the FEM. It has to be noted that the mean absolute error is inflated by the higher values of peak rotational acceleration due to a loss in precision in αpeak superior to 25 krad.s−2. To justify the use of deep learning, a comparative analysis with a simpler linear regression model is provided in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1), highlighting the differences in performance between the two approaches.

Deep learning prediction versus calculated finite element scatter plot (black dots) along with linear regression model fit (red line) and the 95% confidence interval band (shaded red) for a) ωpeak and b) αpeak. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between predicted and FE results are displayed on the plots and were calculated using scipy.stats.pearsonr function from the SciPy library. The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) between predicted and FE results are displayed on the plots and were calculated using the mean_absolute_error function from scikit-learn’s metrics module (sklearn.metrics). It’s calculated as the average of the absolute differences between prediction and FE results.

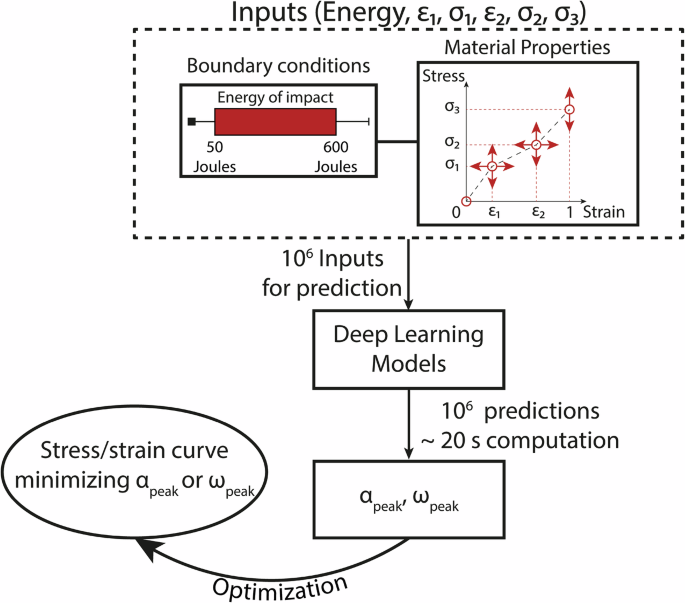

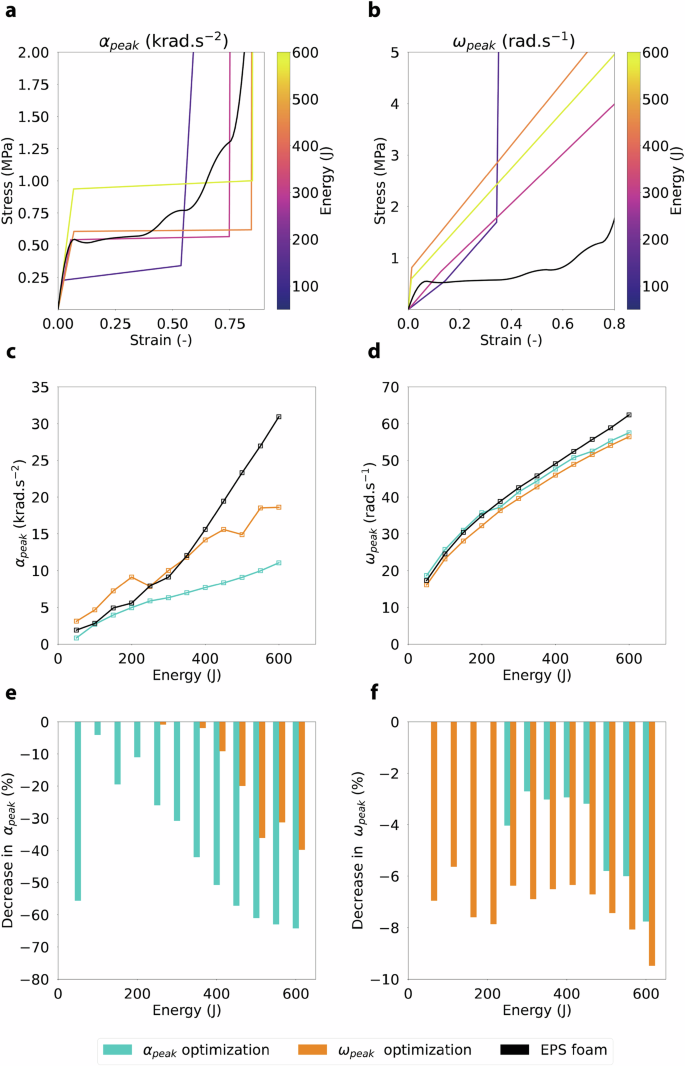

Optimized material properties for the helmet

Figure 3 illustrates the procedure for material properties optimization by employing of the built deep learning models to predict ωpeak and αpeak from a range of impact energies and stress-strain curves data. Deep learning models allow us to obtain rapid and accurate predictions of the kinematic data; 1 million predictions were obtained in less than 20 s. From all these predictions, the stress-strain curves leading to the lowest peak rotational velocity and lowest peak rotational acceleration, respectively, were extracted for a given impact energy varying from 50 to 600 Joules with a 50 Joules increment (Fig. 4a, b). The optimized kinematical data obtained either by using the deep learning model minimizing the peak angular velocity or the deep learning model minimizing the peak angular acceleration were plotted as a function of the impact energy. The kinematical data were compared to the corresponding values obtained the EPS foam presenting a density of 64 kg.m−3, typically used for sports helmets (Fig. 4c, to f).

This process aims to reduce peak kinematic data through the application of the deep learning models developed in Fig. 1.

Optimized stress-strain curves for the pad material minimizing (a) the peak angular acceleration and (b) the peak angular velocity at varying impact energy levels (color-coded from 50 J to 600 J).y. Predicted (c) peak rotational acceleration and (d) peak rotational velocity as a function of impact energy obtained from stress-strain curves minimizing αpeak (blue line) or ωpeak (orange line). The corresponding calculated values for EPS foam (black line) are given for comparison. Reductions in peaks (e) rotational acceleration and (f) rotational velocity when considering constitutive laws for the pad material minimizing the peak velocity (orange) or peak acceleration (blue) compared to the corresponding calculated value of EPS foam.

Effects on brain injury risk

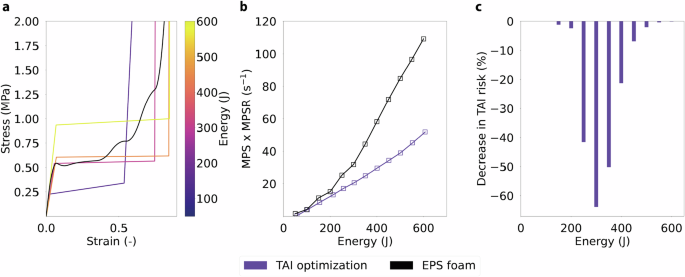

The prediction of ωpeak and αpeak for the millions of used inputs allowed us to derive more specifically the traumatic axonal injury (TAI) risk for each set of inputs. Using Eqs. (1 and 2), the maximal principal strain (MPS) and maximal principal strain rate (MPSR) in the axial plane of the brain were evaluated using the predicted ωpeak and αpeak for each input (stress-strain curves + energy of impact). With the calculated MPS x MPSR value, we evaluated the TAI risk based on Eq. 3. An optimization was then conducted on the TAI to determine stress-strain curves, reducing the TAI risk for each impact energy level (Fig. 5). For every considered impact energy, a material pad with optimized constitutive law highly reduces the predicted MPS x MPSR brain injury metric compared to the results obtained with a constitutive law representing a pad made of EPS foam (Fig. 5b). A clear decrease in TAI risk is visible at impact energies between 250 Joules and 500 Joules (Fig. 5c).

a Optimized stress-strain curves inducing the lowest TAI risk at varying impact energy levels (color-coded from 50 J to 600 J). b Effects of material properties optimization on MPS x MPSR as a function of the energy of impact. As comparison, the MPSxMPSR value for material properties corresponding to EPS foam is reported in blackline. c A different graphical representation of the reductions in TAI risk after optimization of the stress-strain curves compared to EPS foam.

Discussion

This study introduces a deep learning approach, building upon Finite Element Method (FEM) results, to reduce traumatic axonal injury (TAI) risk during a shock, Our unique approach aimed at optimizing helmet material properties based on either kinematical or tissue level injury metrics to minimize impact-induced shock to the brain. Two deep learning models were designed to predict both ωpeak and αpeak. The different values of the two hyperparameter models shown in Table 4 highlight the challenge in predicting the peak rotational acceleration compared to the peak rotational velocity. Despite the disparity in models’ complexity, strong correlations were demonstrated in Fig. 2 and Table 5, underscoring the robust prediction capabilities of both models across a wide spectrum of rotational acceleration and velocities. With strong prediction capabilities, the developed deep learning models can optimize the material properties of helmet pads, specifically the stress-strain curves, to obtain the lowest ωpeak or αpeak across various impact energies.

Optimization results presented in Fig. 4a and b reveal distinct mechanical behaviors in stress-strain curves obtained through ωpeak and αpeak optimizations. Minimizing ωpeak requires a consistent stress increase with strain, whereas αpeak optimization necessitates a stress plateau to reduce the peak rotational acceleration. The results show a clear sensitivity to the kinematical data employed for optimization. Therefore, particular attention should be paid to the chosen variable used in the optimization process while designing a material for protection against TBI.

In this study, we theoretically demonstrated that it is possible to substantially decrease the peak rotational acceleration of a headform after impacts over a range of different energies with a helmet presenting optimized pad material properties compared to the actual liner material made of EPS foam (Fig. 4c–f). The predicted decrease in the peak rotational acceleration ranges from 5% to 60%, with a corresponding rise in impact energy from 100 to 600 Joules representing impact speed from 2.25 to 7.78 m/s. Simultaneously, the effect of the optimization according to the peak rotational velocity is less pronounced when the comparison is made with EPS foam. Finally, the sensibility of the optimal material to the incoming energy of impact enlightens the need to develop innovative materials for helmets with energy-dependent mechanical behavior.

The low absolute error in the predictions of both αpeak and ωpeak enabled us to directly optimize helmet material properties based on TAI risk instead of the head kinematics data. As an illustration, at a 350 J energy impact, a helmet made with EPS foam will not protect against a TAI (99% TAI risk predicted). In contrast, an optimized pad material would substantially decrease the TAI risk to 49% for the same impact scenario. Therefore, the proposed deep learning strategy holds great potential for developing more effective helmets to protect from TAI during head impacts.

Further improvements to the deep learning model are necessary to broaden its scope and accuracy. One potential limitation is that the objective variables were evaluated using only a protective pad instead of a full helmet. Ignoring the rest of the helmet solely to reduce computation time could result in decreased protective efficacy due to shell deformation, force distribution characteristics, and possible contributions from other protective padding.

To obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the material’s effect on reducing TAI, it is important to consider other impact scenarios and material constitutive laws beyond crushable foam. It should be noted that direct modeling of the brain strain after impacts could offer more relevant evaluations of TAI risk by providing a frame-independent calculation of MPS and MPSR, unlike what is followed in Eqs. (1 and 2).

Additionally, our study focused on optimizing material properties for specific impact energies. Future research could explore optimization across a range of impact energies for a single material. The observed compaction at 50% strain for low energy impacts (as seen in Fig. 4a) was surprising and needed further investigation. This behavior could be attributed to the boundary conditions set in our model, possibly representing the edge of the defined input parameter range. Expanding this range to include lower stress levels could provide a more comprehensive exploration of the material’s behavior, potentially leading to improved performance at lower-impact energies.

Overall, this study advances helmet design possibilities to enhance protective capabilities, emphasizing the critical need to understand a helmet’s protective limits for adequate personal risk assessment. Additionally, this deep learning approach offers potential for rapid evaluation of material efficiency against various sport-related injuries. The methodology presented here could contribute to the development of more effective protective gear, improving athlete safety across multiple sports disciplines.

Responses