Structure-guided design of a prefusion GPC trimer induces neutralizing responses against LASV

Introduction

Lassa virus (LASV), the causative agent of Lassa fever, is endemic in parts of West Africa1,2. An estimated 100,000-300,000 people are infected with LASV each year, with 5000-10,000 succumbing to the disease1,2,3,4,5. These numbers are, however, likely an underestimation due to a lack of proper diagnostics in the impoverished, mostly rural, endemic area and the nonspecific febrile symptoms of Lassa fever6. There are currently no approved vaccines or antivirals for the explicit treatment of Lassa fever6,7,8.

There have been some advances in the research of Lassa fever vaccines6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Mateo et al. demonstrated that measles virus vectored-LASV vaccine immunization provides both long- and short-term protection against Lassa fever in cynomolgus monkeys17,18. This vaccine is designed to express the LASV glycoprotein complex (GPC) and nucleoprotein (NP) antigens. INO-4500 is a DNA-based vaccine encoding the LASV (Josiah strain) glycoprotein precursor gene, which was developed by Inovio Pharmaceuuticals19,20. It was the first vaccine candidate to advance to the clinical stage of assessment, undergoing Phase 1a and 1b trials thus far. rVSV-△G-LASV-GPC is a viral vector-based vaccine candidate21. This vaccine uses a recombinant form of the VSV to express the LASV GPC. However, neutralizing immune responses against the GPC for these vaccine candidates range from extremely weak to nonexistent. In contrast, animal studies have demonstrated that the administration of neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) isolated from humans previously infected with LASV conferred 100% protection against a lethal LASV challenge7,22,23,24,25. Given the critical role of neutralizing antibodies in protection, a vaccine might provide enhanced protective efficacy if it can effectively induce NAbs to combat Lassa fever. Recently, the I53-50 nanoparticle system has been used to make nanoparticles of the GPC trimer26, which elicited neutralizing responses in rabbits and guinea pigs after multiple rounds of immunization. This neutralizing response provides a starting point for the further optimization of this structure-based antigen design strategy.

GPC is expressed as a trimer on the viral surface and constitutes the sole target for NAbs27,28,29,30. Following the observation that stabilized prefusion glycoprotein trimers of SARS-CoV-2, HIV-1 and RSV induced strong NAb responses, recombinantly expressed GPC that stably maintains a trimeric prefusion state may represent a promising immunogen to induce potent humoral immune responses against LASV30,31,32. Indeed, the majority of known NAbs target epitopes that span multiple protomers29. Although the development of a prefusion-stabilized GPC constituted an important first step for recombinant protein vaccine design, several challenges remain30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. First, prefusion GPC trimers rapidly dissociate into monomers upon expression, resulting in the loss of NAb epitopes and exposures of immunodominant non-NAb epitopes on the non-glycosylated GPC interior29,30,39,40,41. Second, GPC is covered by a dense glycan shield42, making it a poorly immunogenic antigen. Finally, GPC is sequence diverse, necessitating the induction of broadly NAb (bNAb) responses to neutralize the several lineages of LASV, further complicating the development of an effective pan-LASV vaccine1,2,43.

Here, we describe the design and production of a prefusion GPC trimer antigen from LASV. Using the antigen design principles and the structural characteristics of the prefusion GPC27,31,32, we designed a GPC variant (GPCv2) by replacing the amino acid at position 328 with proline and S1P cleavage site “RRLL” with a G4S linker, in addition to appending the T4 phage foldon trimerization domain. We verified the appropriate structural and antigenic properties of this stabilized GPC trimer. Our experimental results confirmed that a highly expressed prefusion trimer conformation was obtained that retained several important conformational epitopes and stimulated higher levels of specific antibodies, most of which were bound to the GPC-B group epitopes29,30. NAbs were produced in mice after GPCv2 immunization and lasted until 120 days after immunization. Data from immune repertoire sequencing also showed that the induced immune clones in the trimeric group were more convergent and had its own unique V-J pairing bias compared with monomeric group. Furthermore, vaccination with this antigen protected mice from LASV pseudovirus challenge. Altogether, our results highlight the potential of GPCv2 as a promising candidate antigen for an effective vaccine against LASV.

Results

Rational design of recombinant prefusion-stabilized trimeric antigens

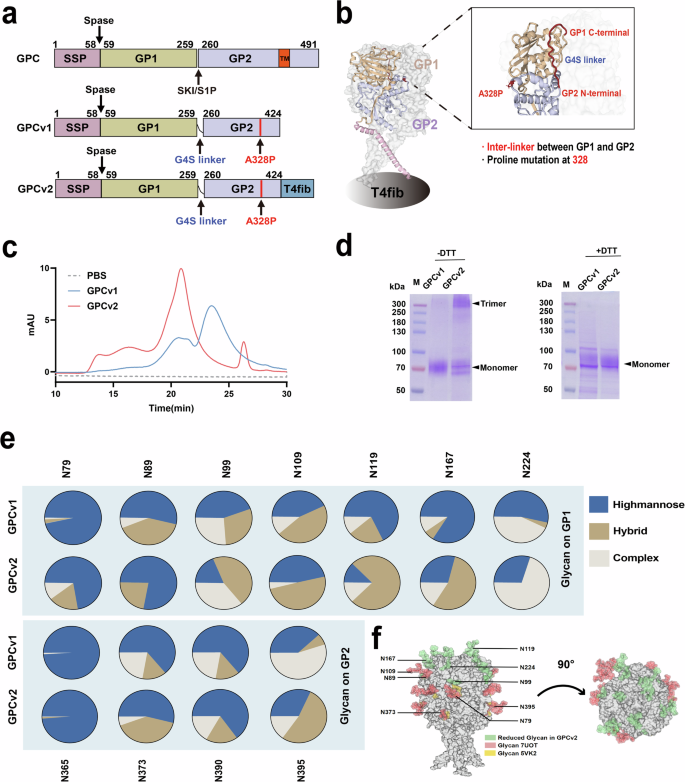

To develop GPC constructs with increased stability in the soluble and prefusion conformation, several mutants were designed based on the ectodomain sequence of LASV GPC (strain Josiah), using the crystal structure of prefusion GPC (PDB: 5VK2 and 7PUY) as a model. Firstly, to improve the stability and avoid the separation of GP1 and GP2, we directly replace the S1P cleavage site “RRLL” with G4S linker. Secondly, to stabilize the soluble recombinant LASV GPC ectodomain in the prefusion states, we introduced a proline at 328 in the turn region of 326-333. Proline substitution in the variable structure region could prevent the conformational transformation of the local unstable region from the prefusion state to the postfusion state31,32. It has proven to be an efficient strategy in design of SARS-Cov 2 Spike, HIV Env, and many other antigens33,34,35,36. This substitution aims to sterically obstruct the refolding process within GP2.

The resulting construct, designated GPCv1 for simplicity, was expressed in Expi293F cells and purified by streptavidin-based affinity purification followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to yield a reasonable amount (~2.3 mg/L) of prefusion protein. Furthermore, to mimic the intrinsic viral membrane structure of GPC, we added a trimerization motif to the C-terminus of GP2, terming the resultant construct GPCv2 (Fig. 1a). The molecular representations of GPCv1 and GPCv2 are shown in Fig. 1b. GPCv2 was also expressed in transiently transfected Expi293F cells and purified with affinity tags followed by SEC. HPLC analysis of GPCv1 and GPCv2 demonstrated that both variants eluted as monomers and trimers, although the latter exhibits more trimeric subunits (Fig. 1c). SDS-PAGE revealed an indistinct trimer band for GPCv1, whereas GPCv2 was exclusively trimeric at an expected size of 300 kDa (Fig. 1d).

a Linear schematic of the GPCv1 and GPCv2 constructs. A G4S linker was inserted between GP1 and GP2; T4fib was fused to the C terminal. b A molecular representation of GPCv2. c A representative elution chromatograph of PBS (gray dotted line) and GPCv1 (blue line) as well as GPCv2 (red line). d SDS-PAGE analysis of GPC v1 and GPCv2 (left: −DTT; right: +DTT). e A comparison of the N-glycosylation profile of GPCv1 and GPCv2. The percentage of each group is shown for each glycosite in the pie chart, and the proportion of each glycoform is shown in the bar chart. f Characteristics of N-glycosylation sites. The diagram illustrates the structural schematic of the modified GPCv2. The orange parts represent the glycosylation sites on the 7UOT structure, the yellow ones show the sites simulated from the 5vk2 structure, and the green ones indicate the glycosylation sites on GPCv2.

Glycan analysis performed via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) revealed the remarkable conservation of glycan composition with these proteins and the previously described GPC27,28,42(Fig. 1e, f). The neutralizing epitopes are usually on the surface of the GPC protein, and the amino acids around them are crucial for NAbs binding. In the case of GPCv1, the proportion of high-mannose glycans is extremely high, especially for those amino acids located around the neutralizing epitopes29,30 (such as amino acids 79 and 119). The proportions of hybrid (brown) and complex (gray) glycans are relatively smaller. Such differences may influence the antigenicity of the GPC protein by altering its surface structure. In GPCv2 samples, the proportion of high-mannose glycans is marginally lower in comparison with the corresponding site of GPCv1.The differences in glycosylation modification between GPCv1 and GPCv2 may have impact on the epitope on the protein surface, and ultimately contribute to the ability of the immune system to generate a robust neutralizing response.

Prefusion-stabilized trimeric GPCv2 exhibits more GPC-B native-like epitopes

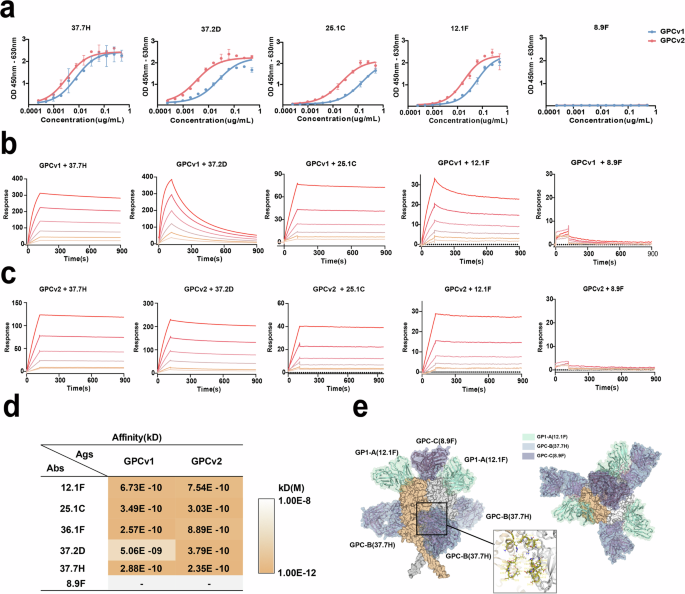

Studies have found that the NAbs for GPC can be clustered into four cross-competition groups, named GPC-A, GPC-B, GPC-C, and GP1-A29.The GPC-A group is composed of the mAb 25.1 C, GPC-B includes 37.2D and 37.7H, and GPC-C contains one mAb, 8.9 F, which competes only with itself. In addition, the GP1-A group includes the mAb 12.1 F. Of these, 37.7H and 37.2D are known to specifically bind to a bipartite site (two adjacent monomers) at the base of the prefusion trimer that spans across four regions of the LASV GPC, while 25.1 C from the GPC-A group engage epitopes located on the region that spans GP1 and GP2 in a single GPC monomer, and 12.1 F contacts a single GP1 subunit on the β-sheet region between β5-β8 and proximal glycosylation sites. While 8.9 F recognizes the receptor-binding domain.

To verify the prefusion conformation of the stabilized LASV GPC trimer and probe the antigenicity of GPCv2, we performed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based binding experiments. A panel of NAbs was immobilized, and binding to an equimolar amount of GPCv2 was assessed (Fig. 2a–c). Of these, all except for the GPC-C antibody 8.9 F were able to bind, suggesting that the stabilized trimer generally possess similar antigenic properties. As a result, we observed markedly improved binding of both mutants to GPC-B group NAbs (37.7H and 37.2D), which not only target an epitope that spans two protomers but also bind to monomeric GPC. Specifically, GPCv2 exhibited better 37.2D binding activity than monomeric GPCv1, which means it may better recapitulate the GPC-B epitope (Fig. 2c, d). These affinity assay results indicate that GPCv2 can mimic the bottom interface, GP1 span, and GP2 and GP1 surface structures of the native GPC trimer (Fig. 2d, e).

a Confirmation of the antigenicity of GPCv1 and GPCv2 using ELISA. b, c Binding profiles of purified GPCv1 and GPCv2 for different mAbs from four groups of human Lassa-neutralizing antibodies: GP1-A, GPC-A, GPC-B, and GPC-C. d Summary of binding affinity. e Location of putative epitopes on a structural model of LASV GPC (surface model). Epitope color code: GPC-B, blue; GPC-C, purple; and GP1-A, green.

GPCv2 can efficiently elicit neutralizing antibodies

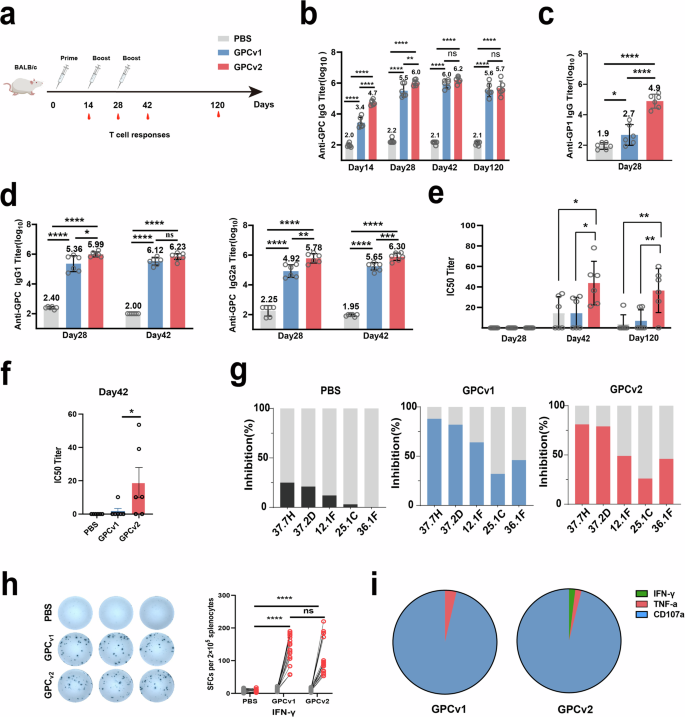

To assess the immunogenicity of recombinant native-like trimer protein GPCv2, we performed an immunization study in mice (Fig. 3a). GPC-specific binding titers were analyzed using ELISA. After the first round of immunization, GPCv2 induced significantly higher anti-GPC IgG titers than GPCv1 (Fig. 3b). A trend toward higher binding titers was also observed after the second round of immunization. After the third round of immunization, anti-GPC titers were very similar between GPCv2 and GPCv1. ELISA titers for both GPC variants stagnated after three rounds of immunization (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, we observed an overall trend toward higher anti-GP1 antibody titers in the mice that received GPCv2 at day 28 post-immunization (Fig. 3c). Since GP1 is interact with receptor α-DG44, which is also implicated in a group of rare congenital muscular dystrophies known as α-Dystroglycanopathies45. Boosting the production of anti-GP1 antibodies may indicate its potenitial application in GP1-related diseases. Beside,an analysis of IgG subclasses revealed comparable IgG1 and IgG2a titers (Fig. 3d).

a A schematic overview of the mouse immunization study. Mice (n = 6 per group) were either mock-immunized with PBS (gray column) or vaccinated with GPCv1 (blue column) or GPCv2 (red column) intramuscularly. The time points for vaccination and bleeding are indicated with appropriate symbols. b–d The antibody response was analyzed with ELISA using the indicated antigen. e Neutralizing antibodies were analyzed in an HIV-based pseudovirus assay. Lines represent the average titers of all animals in each vaccine group. f Neutralizing antibodies were analyzed in LASV minigenome. g Inhibition of binding of the immune sera by the indicated mAbs (37.7H/37.2D/12.1 F/25.1 C/36.1 F). h Splenocytes were extracted at day 35 post-immunization and stimulated with the GL-9 peptides from LASV GPC for IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assays. i Percentage of IFN-γ/TNF-α and CD107a-producing CD4 + T cells at day 14 after the third immunization. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001,****p < 0.0001.

We subsequently used a previously described lentivirus-based pseudovirus assay to measure the induction of NAb responses9. Following three rounds of immunization, all the mice in the GPCv2 group successfully developed NAb titers, with IC50 values ranging from 20 to 80. In contrast, both the PBS and GPCv1 groups still faced challenges in producing NAbs. Furthermore, these titers remained at a high level until day 120 in the GPCv2 group. Besides,the results indicated that irrespective of the adjuvant employed, namely Al+CpG, Addvax, AS01e or R848, the anti-GPC antibody and neutralization titers among GPCv2 immunization group were significantly elevated in comparison to those of the GPCv1 and PBS immunization group (Supplementary Fig. 1).

To further verify the vaccine’s efficiency, we used a previously rescued a recombinant arenavirus model, rLCMV/LASV GPC46, in which LCMV GPC was replaced by LASV GPC. It can offer a more accurate assessment of the impact of antibodies on viral propagation compared to the HIV-based pseudovirus system. Our results have demonstrated that at 42 days post-immunization, the serum neutralization antibody induced by the GPCv2 is significantly stronger than that observed in both the PBS control group and the GPCv1 immunized group (Fig. 3f).

In an attempt to further map the antibody response, we tested the ability of the immune sera to compete with well-characterized GPC-specific human mAbs7,29,30 for binding to GPC by BLI. The following mAbs were used: 37.7H, 37.2D, 12.1 F, 25.1 C, and 36.1 F. Most NAbs against LASV are known to bind the quaternary prefusion assembly of the GPC rather than any single subunit. These antibodies are thought to interfere with viral cell entry by preventing virus binding to the cell receptor or fusion of the viral and host cell membranes.Coated sensors were first incubated with immune sera and then with one of the five mAbs, and the magnitude of binding was measured. All three mAbs appeared to compete with the immune sera from either vaccine group. The purified IgG from sera competed with the four groups of NAbs to varying degrees. The highest binding inhibition percentage on average was seen for 37.7H, followed by 37.2D and 12.1 F (Fig. 3g).

To assess vaccine-specific T cell activation, splenocytes from immunized mice were restimulated with purified protein or the GL-9 peptide in vitro9, and IFN-γ production by splenocytes was examined. Robust GL-9-specific responses were detected in mice either receiving GPCv1 or GPCv2 using ELISpot on day 35 (Fig. 3h). Additionally, splenic lymphocytes were analyzed using intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) on day 42. The numbers of IFN-γ secreting CD4 cells were significantly increased after stimulation with GPC proteins (Fig. 3i).

GPCv2 vaccination protects mice from LASV pseudovirus challenge

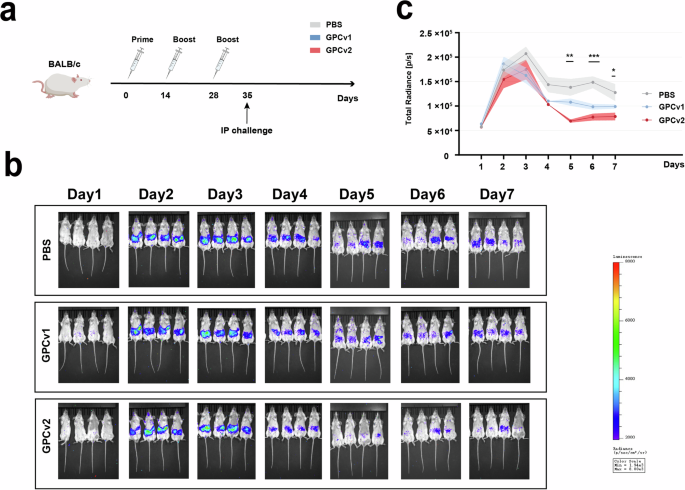

To assess the protective potential of GPCv2, we performed a LASV pseudovirus challenge study, as previously reported9,47. Since the pseudovirus contains the Fluc reporter gene inside, when the pseudovirus enters the cell, the Fluc gene will be expressed to produce luciferase. In the presence of a suitable substrate (such as D-luciferin), the luciferase will catalyze a chemical reaction of the substrate and produce a bioluminescence phenomenon. By detecting the intensity of the bioluminescence, the infection situation of the pseudovirus in the cell and the inhibitory effect of the vaccine on the pseudovirus infection can be indirectly reflected, thus evaluating the effectiveness of the vaccine.

As 10-week-old BALB/c mice can only be infected via the intraperitoneal (IP) route, mice (n = 4) received 20 μg of GPCv1 or GPCv2 adjuvanted in CpG plus Alum on days 0, 14, and 28 (Fig. 4a). Control animals (n = 4) received three doses of PBS. At 5 weeks after the first vaccination, the animals were challenged IP with an HIV-backbone pseudovirus47.

a Workflow of GPCv1 and GPCv2 protective vaccination experiments. BALB/c mice (n = 4/group) were intramuscularly inoculated with vaccines at 0, 2, and 4 weeks, followed by challenge with luciferase-expressing pseudoviruses via the intraperitoneal route at 5 weeks, and they were then imaged at 1 dpi. b Protection against pseudovirus challenge in mice vaccinated with GPCv1 and GPCv2. The first line shows the pseudovirus infection of 10-week-old BALB/c mice as a control. The bioluminescence in the GPCv1 and GPCv2 vaccination groups was imaged at 1 dpi, 1 day apart. c Total flux events in each group were compared. p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The Fluc gene contained within the pseudovirus was initially detected on day 1 and remained detectable until day 7 post-challenge, as depicted in Fig. 4b. Starting from day 5, the fluorescence values in the mice of the GPCv2 immunization group were significantly lower than those in the other two groups. The mice in the GPCv1 group displayed a significantly reduced bioluminescence intensity, which was two-fold lower than that of the control mice. This indicates that the GPCv1 vaccine also conferred some level of protection, albeit not as robust as that of the GPCv2 vaccine. The reduction in bioluminescence intensity suggests that the GPCv1 vaccine may have had an inhibitory effect on the replication or activity of the pseudovirus in the mice, leading to a lower level of viral infection and subsequent bioluminescence emission. These findings highlight the potential of both GPCv1 and GPCv2 vaccines in providing protection against pseudovirus challenge, with GPCv2 showing superior performance in terms of almost complete protection. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action and to optimize the vaccine formulations for more effective protection against Lassa virus infection.

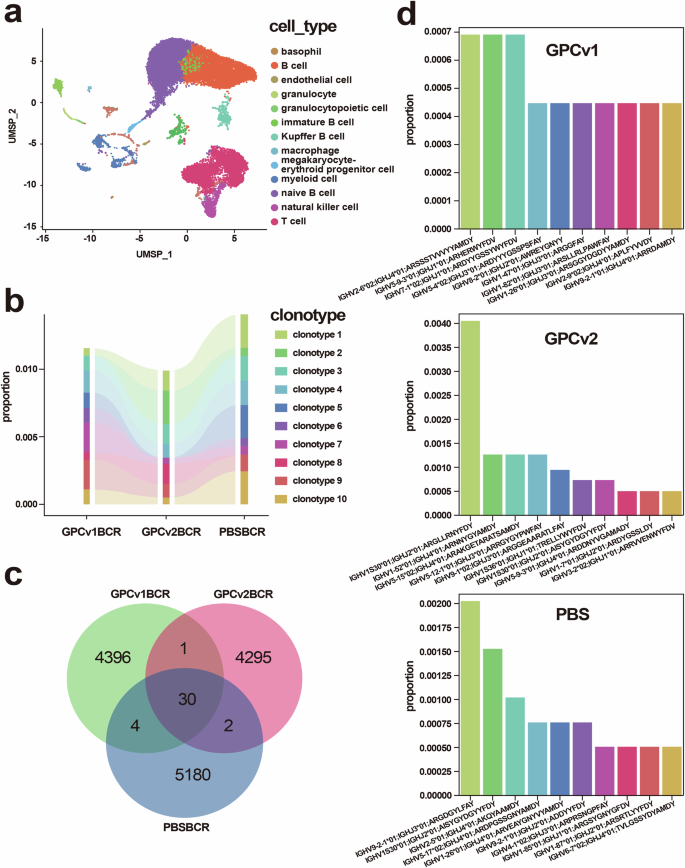

Immunization results in BCR repertoires with different characteristics

B cell receptor (BCR) diversity determines the assortment of antigens recognized by B cells48, and the source of such assortment lies mainly in V(D)J rearrangements and the somatic hypermutation (SHM)49. To obtain more insight into the functional specificity of the Abs, BCR CDR3 sequences from GPCv1- and GPCv2-immunized mice were analyzed to reveal the effects of vaccination on the diversity and immunological characteristics of BCR and the relationship between these alterations and vaccine responses.

BALB/c mice were euthanized, and their spleens were collected for BCR high-throughput sequencing. The alignment ratio of all samples, which is the percentage of reads successfully aligned to the reference genome among all reads was over 70%, indicating that the sequencing results were sufficient for data analysis. Based on the accuracy of Seurat clustering and the automatic annotation of scibet subgroups, the UMAP map of cells was drawn by combining the accumulated marker gene information (Fig. 5a). Then, the obtained VDJ information was integrated with the clustering information for transcriptome library, and the clonotype distribution was evaluated under the grouping state of the transcriptome (Fig. 5b). Based on the results obtained using cell ranger aggr, the clones in each sample were further analyzed, and communication was assessed based on the number of common clones (Fig. 5c). This analysis revealed that the degree of communication between GPCv2 and GPCv1 was significantly higher than with the control group. When facing some common antigens with similar epitope, the immune system may activate specific B cell subsets, and these B cells generate BCRs with similar clonotypes through limited rearrangement methods.

a Representative cell clustering for GPCv1 and GPCv2. b For BCR clonotype analyses, the top 10 contrasts and their proportion between immunized groups and PBS group are shown. c A Venn diagram showing the variety of clones. Comparing the number of shared and unique elements among three samples: GPCv1, GPCv2, and PBS, with the corresponding numbers labeled in different regions of the diagram. d Frequencies of IGHV-J gene pair usage.

When determining whether immunization alters the V-J genes, the preliminary results of the above clonotype analysis showed that IGHV2-6*02: IGHJ4*01 was the most frequently used in GPCv1-immunized mice, while IGHV1S30*01: IGHJ2*01was the most frequently used in GPCv2-immunized mice (Fig. 5d). Therefore, the higher frequency of unique IGHV precursors in the GPCv2 group could be due at least in part to the greater neutralizing responses.

Despite these pronounced differences in clonotypes and VJ-pairing preferences, when we look at the frequency of SHM, there is no significant difference in the overall mutation rate among the groups. Specifically, the sequences with a relatively high mutation rate (greater than 30%) show considerable variation, the numbers are as follows: 10 in the PBS group, 12 in the GPCv1 group, and 18 in the GPCv2 group (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, the specific mechanism remains to be further investigated and elucidated through more in-depth research and experiments.

Discussion

Lassa fever is an acute viral disease associated with severe, life-threatening, multiple organ failure and hemorrhagic manifestations1,6. It has been listed in the WHO R&D Blueprint of priority diseases requiring urgent research and development efforts6. Numerous vaccine platforms have shown protection in animal models against LASV infection6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,26. Nevertheless, the elicitation of effective neutralization antibodies against LASV has posed a substantial challenge. Currently, there is no licensed vaccine for Lassa fever6.

The GPC is the only antigen available for virus-NAbs. It is metastable, conformationally labile, and heavily glycosylated, which impedes the development of vaccines6,27,28. The preservation of neutralization epitopes is important for ensuring efficient induction of NAbs29. As discontinuous epitopes present on structurally mature and properly assembled GPC are the relevant targets for NAbs, the generation of a prefusion-stabilized GPC represents an important advancement for the development of a recombinant protein vaccine for Lassa. Previous studies have shown that structure-based antigen modification design can effectively improve the immunogenicity of vaccines26,30,31,32,33,34,35,36.

Here, we rationally designed a general strategy to retain GPC in the prefusion and trimeric conformation. Incorporating stabilizing mutations into GPC permitted the production of large quantities of GPC retaining a well-folded structure resembling native GPC on the virion surface. GP2 undergoes conformational changes6,27,28,29 between the prefusion and postfusion states, and these spontaneous structural changes hamper the induction of NAbs targeting the prefusion conformation. Moreover, the absence of the trimer-stabilizing helical bundle that is positioned in the center of most viral type 1 fusion glycoproteins, as well as the large cavities in the trimeric interface, likely explains the intrinsic instability of recombinantly expressed prefusion GPC trimers. Incorporating the T4 trimerization motif may reestablish the structural integrity of the trimeric complex50.

We used a structure-based design approach to engineer a prefusion-stabilized GPC trimer by substituting the amino acid at 328 with proline and replacing the S1P cleavage site with a G4S linker and added a trimerization motif T4 fib to the C-terminal of GP2. The resultant GPCv2 protein retained high-affinity binding to a panel of NAbs. Vaccination with GPCv2 induced robust anti-GPC antibody responses, with the GPCv2 vaccine eliciting significantly higher levels of antibodies since day 28. Of note, NAb responses were detected in the GPCv2 group until day 120.We observed an overall trend toward higher anti-GP1 antibody titers in the mice that received GPCv2.GP1 is involved in the binding of the virus to host cell receptors, facilitating virus entry into cells. And liver is one of the main target organs of LASV6,51. LASV can directly damage hepatocytes via GP1-α-DG route, triggering a series of pathological changes such as liver enlargement, apoptotic bodies in hepatic cords and hepatic sinusoids. By boosting the anti-GP1 antibody, GPCv2 shows its potential as a valuable tool in the fight against GP1-related diseases. In addition, vaccinated animals were protected from HIV-backbone pseudovirus challenge. BCR sequencing was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the vaccine, revealing several paired V-J genes. Clarifying the BCR changes induced by this vaccine can provide valuable insight for further improving the vaccine.

Our results also showed that antigens in the trimeric form retained more conformational epitopes and had higher levels of NAbs than in the mono form. These results confirm that modification is beneficial to the production of NAbs.When we examine the clonotypes, it becomes evident that the two groups display marked disparities. In the context of V-J pairing, each group shows particular preferences. Collectively, our findings define a prefusion-stabilized GPC trimer, demonstrating the successful elicitation of LASV-neutralizing responses through a structure-based antigen design approach.

However, this study has several limitations. Although many alternative assessment models have emerged47,52,53, the lack of authentic virus challenge experiment prevents a more comprehensive assessment of vaccine efficacy. There is also still room for improvement, and additional stabilization strategies may be necessary to further enhance the vaccine’s performance. Future work will include a more in-depth investigation of the mechanism of protection induced by prefusion-stabilized GPC vaccines. This could involve studying the interaction between the vaccine and the immune system, the duration and quality of the immune response, and the potential for long-term protection. Additionally, further research could explore the feasibility of combining different vaccine platforms to improve the vaccine’s efficacy and safety profile, Moreover, the application of artificial intelligence techniques can be utilized to assist in antigen design53. Overall, while this study provides valuable insights into the development of a Lassa virus vaccine, more work is needed to translate these findings into a clinically viable vaccine.

Methods

Ethical Statement for mouse experiments

All mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in strict accordance with their policies (IACUC-DWZX-2022-001). Inhalation anesthesia was used in the in vivo imaging experiment. It provides rapid induction and recovery, and the depth of anesthesia can be easily adjusted. Animals are placed in a chamber with a gradually increasing concentration of CO2 to be euthanized. Gradually introduce carbon dioxide in the clean chamber. Monitor the animal. Signs of euthanasia include decreased movement and loss of consciousness. Wait after no signs of life. Handle carcass properly and follow ethical guidelines, avoiding sudden and violent methods that could cause intense pain and fear.

Cells

HEK293T cells were purchased from ATCC. Expi293F cells (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) were subcultured in Expi293™ Expression Medium (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA).

Cloning, expression, and purification of monoclonal antibodies

The structural integrity and prefusion conformation of GPC constructs were assessed with a panel of reference mAbs (37.7H/37.2D/8.9 F/25.1 C/12.1 F). Correctly folded prefusion GPC protein is expected to have an affinity for all of these mAbs. The plasmids encoding the heavy and light chain for each antibody were cotransfected into Expi293F cells using a standard protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific,MA,USA). IgGs were then purified with protein A/G resin.

Expression and purification of LASV GPC mutants

Eukaryotic expression vectors based on pcDNA 3.1/3.4 encoding GPC variant cDNAs were codon-optimized for expression and synthesized. All expression vectors were transiently transfected into Expi293F cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) using the ExpiFectamine 293 transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Cells were grown in polycarbonate baffled shaker flasks at 37 °C and 5% CO2 at 120 rpm. Cells were harvested 6 days post-transfection via centrifugation at 3500 × g for 15 min. The supernatants were filtered with a 0.22 μm filter and stored at 4 °C prior to purification. The GPC variants were purified from culture supernatants using a StrepTrap™ affinity chromatography column (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden), and further purification was performed with a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden).

N-Glycosylation profiling on LASV GPC using mass spectrometry

Initially, samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by the excision of the corresponding gel bands and destaining. The destained gel particles were then subjected to enzymatic digestion with trypsin, chymotrypsin, and Glu-C protease. Subsequently, the processed samples were analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to obtain raw mass spectrometry data. The raw files were then analyzed with the Byonic software (Protein Metrics Inc, CA, USA) to match the data and obtain identification results.

SDS-PAGE

The expression of LASV GPC variant vectors was detected using SDS-PAGE. HEK293T cells were precultured for 24 h in a six-well cell culture plate before all expression vectors were transiently transfected into these cells. The culture supernatant was discarded, and cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and lysed by adding 200 µL of Pierce® IP Lysis Buffer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) containing Halt Protease and a Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) to each well after 48 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and mixed with 6× protein loading buffer (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), and 30 µL of each sample was separated on a 4-12% Bis-Tris protein gel (GenScript, Nanjing, China). The purified protein samples were mixed with protein loading buffer (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). Subsequently, both the denatured and non – denatured mixtures were separated using a 4-12% Bis-Tris protein gel (GenScript, Nanjing, China). After that, the protein gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Bio-Rad).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

Briefly, 96-well high-binding microplates (Corning, NY, USA) were coated with 1 µg/mL LASV GPCv2 protein in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Then, the plates were blocked for 1 h at 37 °C in PBS containing 2% BSA and washed with PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween-20). Mouse serum serially diluted in dilution buffer (PBS with 0.2% BSA) was added to the plates and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (RT). HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Abcam, UK) was diluted 20,000 times and added to the plates. Then, the plates were incubated for 1 h and washed with PBST. The assay was developed for 5 min at RT in the dark using 100 µL of TMB single-component substrate solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and the reaction was stopped by adding 50 µL of stop solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China), followed by the measurement of emission at 450 nm/630 nm (SPECTRA MAX 190, Molecular Device, CA, USA). The endpoint titer was defined as the highest reciprocal serum dilution that yielded an absorbance ≥2.1-fold that of negative control serum values. The endpoint titer were calculated based on the binding curves generated using Prism 10.1.2 software (GraphPad, CA, USA).

Kinetics of LASV mAb binding

mAb-binding analyses were performed on a Biacore 3000 (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). A GE Healthcare Sensor Chip Protein A was coated with 1 μg/ml of anti-GPC. Interaction analysis was performed by injecting recombinant LASV glycoproteins at concentrations that produced a response between 50 (Rmin) and 200 (Rmax) “response units.” The flow rate was 5 ml/min in a HEPES-EP buffer (pH 7.5). Once the proteins were covalently immobilized, the flow rate was increased to 15 ml/min. Varying concentrations of LASV mAbs were then injected, and kinetic parameters were determined using a bivalent binding curve.

Mouse immunization

To evaluate the humoral response, female BALB/c mice were immunized intramuscularly with a dose of 100 μL vaccine formulation containing 20 μg protein,100 μg Alum (Brenntag Biosector, Denmark) and 20 μg CpG 1826 (InvivoGen, France) three times. Serum was collected for LASV GPC-specific ELISAs and LASV NAb titer 14,28,42 and 120 days after the first round of immunization.

HIV-based pseudovirus assay

LASV pseudovirus bearing the full-length GPC was generated in an env-defective, luciferase-expressing replication-incompetent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 backbone. Briefly, pDC316-LASV-GPC and pNL4-3.Luc-R-E were co-transfected into 293 T cells using TurboFect (Thermo Scientific, R0531). The pseudovirus-containing supernatants were harvested and supplemented with fresh medium at 48 and 72 h. The LASV pseudovirus was filtered, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. Serial dilutions of heat-inactivated sera and titrated pseudovirus were co-incubated for 60 min at 37 °C and added along with the 293 T cell suspension to 96-well microplates. Luciferase activity was measured using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) neutralization titers were calculated for each mouse serum sample using the Reed-Muench method.

rLCMV/LASV assay

Recombinant LCMV (ARM strain) expressing LASV GPC were generated by reverse genetic techniques, as previously reported46. Briefly, Vero cells were seeded in a 48-well plate. On the next day, the cells grew to cover 90% of the bottom of the wells. The serum samples to be tested were diluted with serum-free high-glucose DMEM medium. The initial dilution was 10-fold, and then serial 3-fold dilutions were made for a total of 6 gradients. The recombinant LCMV virus carrying GFP of LASV was diluted with serum-free high-glucose DMEM medium to a titer of 1000 PFU/mL. Then, 100 μL of the diluted virus was added to the diluted serum. At this time, the volume of the serum-virus mixture was 220 μL. The mixture was then incubated in an incubator at 37 °C for 1 h. The medium in the 48-well plates was removed. Then, 100 μL of the liquid from step 2 was added into each well of the plates. For each dilution gradient, two replicate wells were set. The plates with the added liquid were then placed in an incubator at 37 °C and incubated for 1 h. After incubation, the liquid was removed. Then, 100 μL of sterile PBS was added into each well for washing. After discarding the PBS, 0.5 mL of high-glucose DMEM medium containing 1% methylcellulose and 10% FBS was added into each well. The plates with the added medium were placed in an incubator at 37 °C. Finally, the number of fluorescent plaques was counted under a fluorescence microscope.

T cell response assessment

Mice were sacrificed and splenocytes were isolated through a 70-μm cell strainer. As described previously9, 2.0 × 106 cells were stimulated for 6 h at 37 °C with or without GL-9 dissolved in DMSO (20 µg/mL) or with an equal volume of DMSO as a negative control and then incubated with BD GolgiStopTM for 4 h. Following washing with PBS, cells were stained with the LIVE/DEADTM Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen, USA). The cells were washed with PBS, blocked with Mouse BD Fc BlockTM, and then incubated with anti-mouse antibodies (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) including PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD3 (clone 17A2), FITC anti-mouse CD8a (clone 5H10-1), and Brilliant Violet 421TM anti-mouse CD107a (clone 1D4B), diluted in Cell Staining Buffer (Biolegend). Following simultaneous fixation and permeabilization with Cytofix/CytopermTM Fixation and Permeabilization Solution (BD), cells were incubated with phycoerythrin (PE) anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), APC anti-mouse TNF-α (clone MP6-XT22) diluted in 1× Perm/WashTM Buffer (BD). Flow cytometry was performed using a BD FACSCanto and analyzed by FlowJo 10 software.

ELISpot

Peptide-specific T cells were counted using a ELISpot Mouse interferon (IFN)-γ Kit9. Briefly, the cell suspension and the stimuli were added to a 96-well ELISpot plate (Mabtech, Sweden) coated with IFN-γ antibody, PMA and deionomycin (Dakewe Biotech Co, Ltd) were added as positive controls, and the cells incubated without stimuli were used as negative controls. The ELISpot plates were incubated in a cell incubator for 36 h. The supernatant was discarded, the plates were washed 5 times with PBS, and the biotinylated antibody was added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded, the plate was washed as above, and the HRP secondary antibody was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The supernatant was discarded, the plate was washed as above, TMB chromogenic solution was added for 5-15 min at 37 °C, and the plate was washed with plenty of deionized water to stop the chromogenic reaction. Then place the plates to dry, and AT-Spot 3200 (Antai Yongxin Medical Technology, China) were used for capture images of the spots in each well and the analysis.

BCR sequencing

Seven days after the third immunization, single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were prepared as described earlier9. Then, 2 μg of RNA from each sample was used to prepare the VCR library using Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Reagent Kits. Duplication bias was eliminated using unique molecular identifier sequences consisting of eight random bases to tag the pre-amplified cDNA. After this, NovaSeq (Illumina) was used to sequence the 250-500 bp library products. Raw data were filtered using SOAPnuke (version 1.6.0) first, and low-quality reads were discarded. Consensus sequences were finally extracted and subjected to BCR-seq analysis. Reads were mapped to the international ImMunoGeneTics database using the MiXCR software (v.3.0.3) to obtain V, D, and J gene fragments and CDR3 sequences. To quantify the BCR clones that were most frequently expanded, IgH sequences that used the same V(D)J alleles and had ≤1 mutation in the CDR3 region were clustered. The top 100 dominant BCR clones were then identified. The IgBLAST and IMGT germline sequence databases were utilized to assign V(D)J gene annotations to the BCR FASTA files for each sample. SHazaM in ImmCantation toolbox (v4.0.0) was used to estimate BCR mutation frequencies.

Statistical analysis

All assays were performed with at least three separate replicates, and the data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (version 10.1.2) and R Package rstatix (version 0.7.2). Ordinary one-way ANOVAs with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test or Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to assess statistical significance among groups. The used statistical tests are shown in the related figure legends: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001,****p < 0.0001. Venn diagrams were plotted from the exported data.

Responses