Product and trial design considerations on the path towards a vaccine to combat opioid overdose

Introduction

Opioid overdose remains a leading cause of injury-related death in the United States (U.S.). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed that overdose deaths reached a new 12-month record, with >100,000 deaths in 2022: the percentage of overdose deaths involving fentanyl or fentanyl analogs ranged from 75% to 79% from 2000 to 2013, then increased from 81% in 2014 to 96% in 20221. Unintentional drug overdoses resulted in >1.25 million years of lost life for US preteens, teens and young adults (10–24 years old) between 2015 and 2019, with fentanyl exposure a leading contributor to overdose, signaling an alarming trend in this vulnerable population2. In 2023, a decrease in drug overdose deaths was observed for the first time since 20183. Several efforts are underway to develop novel preventive and therapeutic approaches to further reduce morbidity and mortality due to opioid use4. Here we provide an overview of the process and considerations towards development of a vaccine to prevent fentanyl overdose deaths.

Pharmacologic effects of fentanyl

Fentanyl is a mu (μ) opioid agonist that is ~50–100 times more potent than morphine and was originally developed to meet a need for a more effective pain medication for patients at the end of life5. Synthetic fentanyl is relatively easy to produce. Much of the fentanyl material involved in overdose is produced illicitly, and in many cases, is a contaminant of other drugs like heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and counterfeit products6. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) warns that many counterfeit pills are indistinguishable from prescription opioids such as oxycodone (Oxycontin®, Percocet®), hydrocodone (Vicodin®), and alprazolam (Xanax®); or stimulants like amphetamines (Adderall®)7. Counterfeit pills are easy to purchase, are often sold on social media and e-commerce platforms, often contain fentanyl or methamphetamine, and can be deadly6,8. The widespread availability has facilitated access to youth, including those who do not have an opioid use disorder (OUD). In fact, 65% of youth who fatally overdosed in the U.S. between 2019 and 2021 had no known opioid use prior to the overdose event9. Because of its high potency, even small amounts of fentanyl (2 mg) can cause lethal respiratory depression within minutes of exposure10.

Pharmacological derivatives of fentanyl include sufentanil, remifentanil, alfentanil and carfentanil. Of these, sufentanil, remifentanil and alfentanil are all used for human anesthesia. Carfentanil is ~10,000 times more potent than morphine and although it is only used in veterinary medicine, it has been detected in lethal opioid poisonings of humans; standard panels do not test for carfentanil hence tallies are likely underestimates11. Given carfentanil’s very high potency, there is the potential for it to be used as a chemical weapon12. There is also a long evolving list of “designer” fentanyl, sometimes called “non-pharmaceutical fentanyl.” These are illicitly produced compounds with no medical use.

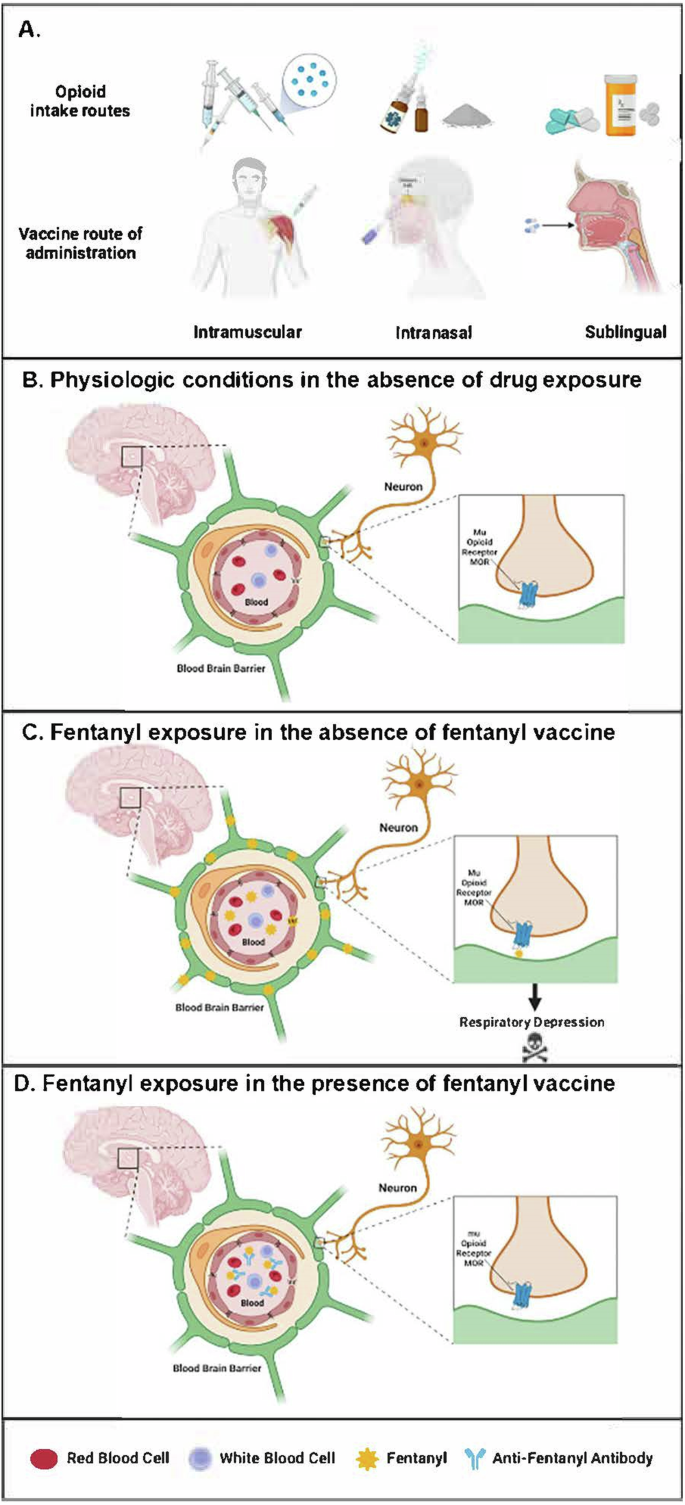

Exposure to fentanyl (and other synthetic opioids) can be intentional or unintentional, and the drug is mainly ingested orally, insufflated intranasally, smoked or administered intravenously. Regardless of delivery route, fentanyl readily crosses the blood–brain barrier (BBB) stimulating μ-opioid receptors (MORs) in the brain, thereby eliciting analgesic effects13. MOR binding also induces on-target side effects including euphoria, sedation, and the development of drug tolerance and withdrawal symptoms of abstinence. Excessive MOR activation by opioids in the brain causes respiratory depression, the primary cause of drug overdose deaths (Fig. 1)14,15.

A There are multiple opioid intake routes for medical and non-medical uses, including injections, nasal administration and oral tablets; therefore, different opioid vaccine administration routes should be studied. B Mu opioid receptors (MORs) are expressed on neurons within the respiratory network of the brain in close proximity to the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a semipermeable barrier that regulates the transfer of solutes and chemicals between the circulatory system and the central nervous system to protect the brain from harmful or unwanted substances in the blood. C Opioids such as fentanyl cross the BBB and interact with the human MOR at the neuronal synapse, ultimately causing respiratory depression. D Vaccine-induced anti-fentanyl antibodies bind fentanyl in the blood and prevent it from crossing the BBB, thus mitigating its respiratory suppressive effects. Created using BioRender.

Existing overdose treatment and prevention strategies

The only available Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved options to acutely treat respiratory depression from fentanyl overdose are nalmefene (FDA-approved in May 2023) and naloxone. Both are fast-acting antagonists (nalmefene has a ~5 times longer half-life than naloxone) with high affinity for the MOR and can be administered intranasally (IN), via intramuscular (IM), or intravenous (IV) injection. Both are rescue medications that must be given within minutes of an opioid overdose to reverse opioid-induced respiratory depression and prevent death. Both also require availability of a prepared and willing bystander who can administer them. People who have been revived from an overdose may overdose again when rescue medications wear-off. Naltrexone, a long-acting MOR antagonist indicated for the treatment of OUD in patients over the age of 18 years, is available in an extended-release IM formulation. Naltrexone is increasingly being used off-label at monthly intervals to prevent opioid overdose among individuals thought to be at risk of opioid overdose, but this formulation blocks the action of all opioids, potentially complicating anesthesia in unplanned or emergency situations16.

Other than rescue treatment options for opioid overdose, harm reduction strategies may lessen the risk of adverse outcomes associated with drug use behaviors. Strategies encompass provision of sterile syringes to reduce risk of infection for injecting drug use, distribution of naloxone to reverse overdose, education about illicitly manufactured fentanyl and its derivatives, and promotion and distribution of fentanyl test strips17,18,19. Fentanyl test strips can be used by people who intend to ingest drugs to detect the presence of fentanyl or fentanyl analogs in a substance20. However, effective use of fentanyl test strips requires access, knowledge, and planning, factors that may undermine use given that drug use behaviors may be impulsive and opportunistic, especially among sporadic users. Although prevention of opioid overdose is a public health priority, harm reduction strategies are mostly designed for individuals who have drug use disorders, yet many persons at risk of opioid overdose may not have a substance use disorder (SUD) or known history of opioid use9,21,22,23,24.

Potential vaccination approach for prevention of lethal fentanyl overdose

Prevention strategies such as vaccination are critical approaches to address public health threats, especially infectious diseases. Vaccine immunogenicity protects the host against future exposures. Similarly, in the case of opioids, vaccines that induce high-affinity, fentanyl-specific antibodies, using a fentanyl-like small‐molecule protein immunoconjugate – (i.e., a hapten approach, combined with an adjuvant to enhance magnitude and durability of immunogenicity) have been developed and tested in the pre-clinical setting25,26,27,28,29,30. Specific anti-fentanyl antibodies in the peripheral circulation can bind the circulating drug before it crosses the BBB where the MORs are located (Fig. 1).

Given the limitations of existing strategies to prevent fentanyl overdose deaths, fentanyl vaccines could complement existing overdose prevention strategies, augmenting current approaches through a model centered on passive protection. Optimally formulated, a fentanyl vaccine may offer longer lasting protection (reducing patient burden and non-adherence) and narrower focus (sparing the action of other opioids if emergent pharmaceutical intervention is needed) compared to opioid antagonist medications which at times are used off-label in this capacity. Furthermore, the antigen target(s) within a putative opioid vaccine formulation could also be updated periodically to create a multi-valent vaccine based on surveillance to monitor emergence of novel illicit drug use.

Preclinical proof of concept for opioid vaccination as a treatment for SUD was first demonstrated in 1974, when a morphine‐bovine serum albumin (BSA) conjugate vaccine modestly attenuated self‐administration of heroin by Rhesus monkeys31. However, it was not until the 1990s, in the context of renewed interest, that vaccines for cocaine and nicotine were advanced to clinical trials. Although these initial efforts aimed at treatment of the target addictions, the concept of using opioid vaccines to prevent overdose has only recently been considered (Supplementary Table 1). Featuring recent advancements in drug conjugate vaccine design and novel adjuvants that induce sufficient antibody production to effectively sequester a hapten opioid in the periphery, second generation vaccines have demonstrated substantially improved performance in preclinical models, thus renewing the potential clinical utility to target opioid overdose32,33.

Adjuvanted conjugate vaccines generate antibodies with long half-lives, far outlasting the metabolism and elimination of small‐molecule therapeutics. Moreover, because immunopharmacotherapy primes the body’s own immune system to curb opioid effects, an adjuvanted conjugate vaccine approach raises the possibility of developing a product with minimal side effects, as shown in other anti-drug vaccine studies for other conjugate and adjuvanted vaccines administered to mice and non-human primates34,35. Thus far, adjuvanted conjugate vaccines have demonstrated selectivity for the target opioid in preclinical studies, suggesting that they should not interfere with endogenous neuropeptides nor with medications used for treatment of OUD or reversal of overdose36.

In addition to vaccine conferred immunity, the protective effects of antibodies against opioids have also been demonstrated through passive immunization with opioid monoclonal antibodies (Box 1).

Individual vaccine characteristics

Target population

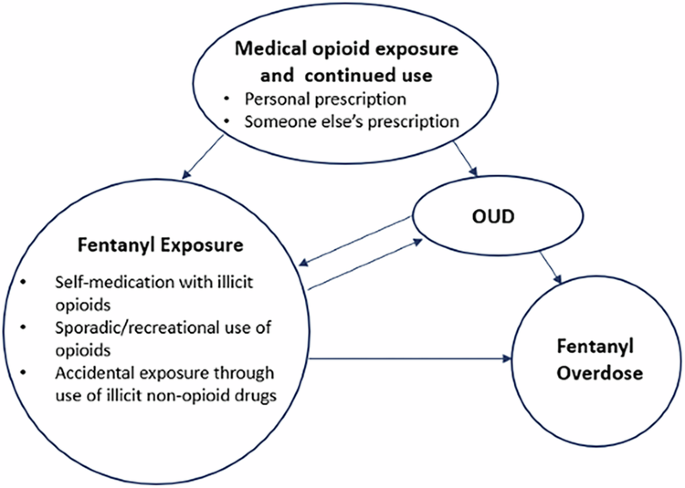

Persons with OUD constitute the population at greatest risk for overdose (Table 1). Depending on their internal motivations, beliefs, and acceptability of an opioid vaccine, this group would likely gain the highest benefits from opioid vaccination. Of note, some at risk individuals, including ~65% of adolescents (under 18 years) who die of opioid overdose do not carry a diagnosis of OUD and are not known to have previously used opioids. Thus, the population that could benefit from an opioid vaccine is substantially larger than the OUD population. Indeed, several other risk factors are associated with increased risk of opioid overdose, including but not limited to, being a recipient of an opioid prescription, being a family member of someone who is on prescribed opioids, having a family history of overdose or having a personal history of other substance use disorders (Fig. 2), and overall, 80% of lethal opioid overdoses involve fentanyl37. First responders and military personnel could be considered additional target populations who may benefit from an opioid vaccine given their potential exposures including the risk of weaponization of opioids such as occurred at the Moscow Theater Crisis of 200212,38. Tapering or abruptly stopping opioid prescribing in patients on long-term opioid treatment and co-prescription of other psychotropic medications, are all associated with increased risk of overdose39. This at-risk population will be more heterogeneous; therefore, risk-benefit ratios may be case-based and would require shared decision-making between the recipient and their primary healthcare provider.

(OUD = opioid use disorder).

Vaccine efficacy/Immunogenicity

Recent studies in mice and rats have shown protection from lethal challenge with fentanyl and selected analogues following vaccination with fentanyl vaccines32,40,41,42. Based on the limited experience in this field and of pre-clinical studies, production of antibodies with adequate concentration and drug affinity will likely be critical correlates of protection and can serve as measures of immunogenicity in opioid vaccine human studies43. Although opiates and opioids modulate the innate immune system with correlation to reduced anti-viral responses and increased susceptibility to infections, we are not aware of any published studies suggesting that people with OUD have reduced vaccine immunogenicity44,45. Nevertheless, vaccine efficacy in immunocompromised populations could be improved by optimal adjuvant design27 (Box 2).

Vaccine induced immune responses against opioids will rely on the humoral response and antibody efficacy in preventing the target drug from crossing the BBB. Antibodies could prevent the target drug from crossing the BBB multiple ways, including a) by binding to circulating opioids preventing them from interacting with cellular signaling pathways, or b) by binding opioids at mucosal membranes preventing passage to underlying tissues and the systemic circulation.

Initial explorations into opioid vaccine development have also found important correlations between antibody isotype and protection against opioid overdose. In vivo experiments with adjuvanted vaccine formulations have found that IgA plays an important role in protecting against opioids with serum IgA levels strongly correlating to reductions in brain fentanyl levels32. Given that secretory IgA is typically found in mucosal tissues, where most IgA secreting plasma cells reside, as opposed to its freely circulating secreted form, its role in protecting against opioid overdose may be greater than currently understood27. In particular, the meninges serve as a barrier protecting the brain from circulating pathogens and toxins and have an immune profile largely dominated by IgA similar to the IgA profile found in the gut41. A meningeal IgA profile, including anti-fentanyl IgA, may be an important player in preventing opioids from crossing the BBB.

Given the dynamic nature of a metabolically active drug in the human body, efficacy will also largely depend on drug pharmacokinetics and how well antibodies against the parent drug also target its daughter metabolites, as well the physicochemical properties (lipophilicity, molecular size, depot effects, etc.) of the vaccine product and its constituents.

The endpoint measurement of vaccine efficacy needs to be measurable and clearly defined. When the outcome of interest is immunogenicity, i.e. in cases where a given clinical outcome is rare or hard to capture, endpoints commonly used in clinical trials are the proportion of individuals mounting an immune response (compared to standard of care or placebo) or geometric means of antibody concentrations. When the endpoint measurement is a clinical outcome, vaccine efficacy is generally reported as a relative risk reduction (RRR) expressed as 1–relative risk (RR), where RR is the ratio of attack rates with and without a vaccine. It is critical to note that RRR applies to and should be interpreted within an at-risk population, i.e. the actual absolute risk reduction (ARR) and benefit from vaccination will be much smaller in the context of the general population. For a vaccine such as a fentanyl vaccine that is geared towards a high-risk population exposed to opioids and not intended for universal use, the RRR and ARR would be similar. The number needed to vaccinate (NNV), calculated as the inverse of ARR, may provide a better sense of vaccine effectiveness in real-world settings for an acute and lethal outcome such as opioid overdose. Measuring the exposure to fentanyl pre-and post-vaccination can be used as an endpoint to evaluate the magnitude of change in drug use behavior.

Dosing schedule

The “optimal” vaccination schedule (number of doses), conferring adequate immunogenicity with minimal/acceptable adverse events (AEs) is not known since fentanyl vaccines have not yet been tested in humans. The target product will ideally consist of as few doses as possible to optimize adherence43,46. Fewer vaccine doses are highly desirable and may be important for real world implementation, especially in the highest-risk populations, such as those with OUD or other SUDs, who are often exposed to limited or interrupted access to healthcare resources, as well as housing instability or homelessness47.

Duration of protection

According to prior studies of cocaine and nicotine vaccines, antibody half-life may be variable, but high initial titers (post-prime vaccination) are highly desired and can partially compensate for short-lived antibodies43,48,49. Ideally, antibodies should be detectable for at least 6 months-1 year, at which time a booster dose may be needed depending on the longevity of the immune response and the risk of re-exposure. Establishing a correlate of protection could be utilized to enhance protection over time. Phase 2 clinical trials will be needed to determine the neutralizing capacity and stability of these antibodies.

Vaccine safety/reactogenicity

Vaccine safety is always a priority in vaccine development. During early stages of pre-clinical development, vaccine candidates need to demonstrate lack of significant agonism with opioid receptors in vitro to minimize the possibility of inherent opioid effects. Similarly, vaccine candidates need to demonstrate lack of analgesic effects in animal models amenable to behavioral testing (e.g. rats, pigs) in vivo. Efforts should be pursued to test and mitigate any cross-reactivity between anti-drug antibodies and endogenous or exogenous moieties, such as non-targeted opioid drugs or medications (i.e. methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone and naloxone) to avoid interactions with medically indicated therapies or medically assisted treatment protocols that are commonly followed to treat OUD/SUD. It would also be advantageous for a vaccine to not induce antibodies to sufentanil, remifentanil or alfentanil so that these medications can be used as anesthesia alternatives in vaccinated individuals. However, antibody cross-reactivity against carfentanil and designer, non-pharmaceutical fentanyl, which play no role in human medicine, may be highly desirable; but may vary based on the hapten-pharmacophore-conjugate formulation. Fidelity to target binding and minimal to no vaccine off-target effects are important.

Once immunogenicity, toxicology and formulation have been fully assessed in pre-clinical models, Phase 1 clinical trials are necessary to assess safety and tolerability in humans. Safety assessments may include regularly scheduled complete blood counts, chemistries, electrocardiograms (EKGs), urine drug screens, as well as local and systemic reactogenicity assessments with close monitoring of participants. In addition, theoretical vaccine off-target effects including the impact of vaccination on endogenous pain responses may be incorporated in safety assessments to determine the implications for exogenous pain relief if circumstances arise. Lastly, attention may be paid to any emergence of autoimmune conditions given the small size of opioids and a theoretical risk of vaccine-induced antibody cross-reactivity with auto-antigens.

Stability/shelf life

To achieve reasonable target population penetration, opioid vaccines may need to be administered from mobile vans, at needle exchange programs and STI (sexually transmitted infection) clinics in addition to traditional medical settings and therefore stability at a wide range of temperatures is desirable. This would also enable access and distribution to persons who may benefit from the vaccine, but live in rural and medically under-served areas via community outreach/mobile clinics50.

Route of vaccine administration

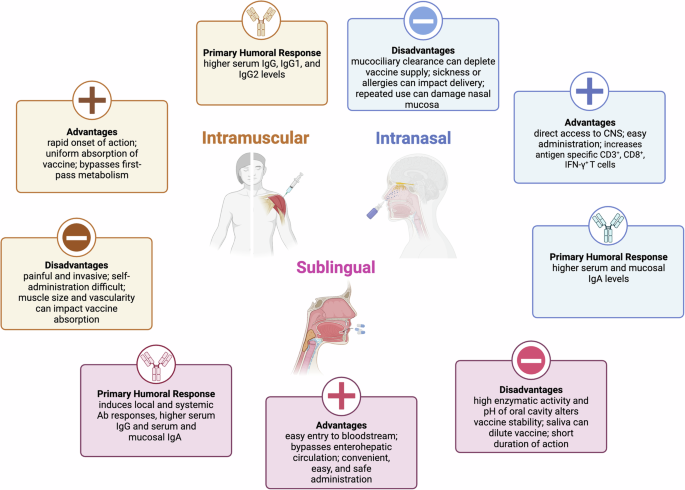

Intramuscular routes are typically the initial routes evaluated in the vaccine field (Fig. 3). As research and development of formulations continue, other routes are often explored. As exposure to opioids may be through mucosal sites, and given recent supportive murine studies32, a mucosal opioid vaccine remains an appealing target, but has yet to be developed and tested for prevention of opioid overdose. Mucosal immunization (i.e. oral, intranasal) has been successfully deployed for human vaccination against infectious pathogens (e.g., influenza and cholera) and has several advantages, including combined induction of humoral and cellular immune responses at the local (mucosal IgA) and systemic (serum IgG) levels51,52,53,54 Possible binding of the target drug at the time of exposure prior to systemic absorption, as well as its non-invasive nature can improve compliance.

(CNS central nervous system.) Created using BioRender.

Intranasal vaccine delivery has not yet been tested for opioid vaccines but remains a desirable route of administration32,55. The olfactory region of the human nasal cavity enables direct and rapid nose-to-brain drug transport primarily along the olfactory neurons, while its highly vascularized respiratory region enables systemic absorption into the bloodstream through the lung, gastrointestinal and lymphatic compartments56. Intranasal administration of vaccines has been shown to induce both localized and systemic immune responses through the stimulation of nasal associated lymphoid tissue, commonly activated in the response to respiratory pathogens, and may pass these responses to other mucosal sites57. Benefits of intranasal administration include a) the ability to deliver liquid or powder formulations which can reduce cold chain requirements, b) avoidance of gastrointestinal tract metabolism, and c) amenability to use of small molecules which cannot be given either orally or by injection57. Vaccine acceptability may also be enhanced as nasal administration is non-invasive causing little discomfort, making it a good option for children, older adults, and people sensitive to injections58. Sublingual administration may be an alternative route of administration as it has been shown to elicit IgA responses in opioid vaccine studies32,55. Neither route is without its challenges, however. The locality of the nasal membranes close to the olfactory bulb could give certain compounds the ability to bypass the BBB and gain direct access to the central nervous system; therefore, route-specific toxicology studies would be needed, while sublingual administration can face similar metabolism hurdles as oral medications57. In addition, other challenges of mucosal delivery systems include a tendency for immunological tolerance as mucosal systems are constantly exposed to pathogens and are adapted to remove them through cilia and other defensive pathways59,60, though the relevance of these with regards to opioid vaccines has yet to be determined. In conclusion, combination of mucosal and traditional (i.e. IM) immunization routes in a heterologous prime-boost approach should be considered and could lead to a more diverse immune response with fewer vaccine doses.

Phase 1 clinical trial design considerations

Fentanyl vaccines for overdose prevention have not been evaluated in humans. A first-in-human Phase 1 clinical trial may entail careful planning and consideration of several factors. Within the scope of Phase 1 studies, safety remains the primary endpoint and selection of the target population may include participants who are at low risk for adverse medical consequences, but still at increased risk for the condition of interest (fentanyl overdose) compared to the general population (Table 2). Figure 2 provides a suggested framework for selection of a trial population within the framework of a U.S. FDA Investigational New Drug (IND)-enabled clinical trial. Choice of the target population will also determine the likelihood of co-exposures (less are desirable), recruitment feasibility, loss to follow-up, adverse events and the most appropriate setting for study conduct. There are several vaccine- and population-related safety considerations61. Fentanyl would become impractical or impossible to use for anesthesia in vaccinated individuals, but could be substituted by other anesthetics, provided there is no or minimal cross-reactivity with other drugs. Although induction of high and long-lasting antibody titers is desirable, the focus of a Phase 1 study would be to evaluate safety and tolerability. In summary, a top-down approach with a candidate vaccine conferring maximal immunogenicity tested in a Phase I clinical study with an adjuvant dose escalation scheme can lead to selection of an effective and safe product for use in future Phase Ib/2 studies. Significant community involvement through the establishment and incorporation of a community advisory board may provide further input to ensure relevant issues for the population have been considered.

Ethical considerations

As with any vaccine, attention to principles of autonomy, beneficence, informed consent, and protection from coercion are vital. In the case of a fentanyl vaccine, it will be necessary to incorporate mechanisms that support education about the vaccine and shared decision-making regarding eligibility and suitability for use, including to determine vaccination contraindications based on intention to continue using fentanyl out of medical necessity or as a drug of choice for persons who use illicit drugs. The possibility of altered metabolism of fentanyl over time and re-emergence of drug use behaviors with ensuing implications for future overdose risk when vaccine-induced immunity may have waned should be acknowledged and addressed. Consideration of when to offer the vaccine is important so that physical conditions do not cloud or reduce competence; for example, guidelines for vaccination that protect against decision-making during periods of potentially reduced competence, such as immediately following an overdose, may be needed, along with guidelines for protecting against conditioning entry to substance use treatment or avoidance of incarceration contingent upon vaccine acceptance.

Potential strengths and limitations of opioid vaccines

The scientific premise for the vaccine’s mechanism of action is production of antibodies that bind the target drug, fentanyl, in the peripheral blood or at the mucosal tissue level and reduce its ability to enter the brain, thus protecting participants from respiratory depression due to overdose. Prevention of the drug from reaching its receptor in the central nervous system will likely block the euphoric effects that ensue after use, potentially dissuading its use among individuals with OUD. In addition to saving lives, indirect benefits of a vaccination approach to combat opioid overdose may include a boost in general public awareness around substance use and SUD46. While not curative, an opioid vaccine approach may significantly reduce the burden of opioid overdose morbidity and mortality and subsequently lead to significant cost-savings as measured by quality-adjusted life years.

Along with considerable strengths, a vaccination approach will also face challenges. Based on the kinetics of the humoral immune response, immunization must occur 2–4 weeks prior to fentanyl exposure to allow for immune induction and isotype switching from IgM to IgG to be effective. There needs to be careful consideration of suitable target groups, given the promise of immunization when considered against other practical, clinical, epidemiological and ethical considerations. Indeed, those at greater than average risk of opioid overdose may be particularly tractable. Lastly, there is a need for strategic communications around opioid vaccines addressing the limitations, unknowns and the need for individualized decision-making in high-risk groups62.

Beyond the challenges and opportunities pharmacology offers, tackling opioid and other SUD requires attention to the root causes of the addiction crisis. This includes the integration of psychosocial interventions, such as behavioral therapy and community support, and new technological advancements rooted in biomedical product development. Government and industry research support should aim to accelerate innovation in the space of SUD prevention.

Conclusions

Vaccination strategies are known to be generally scalable, cost-effective, and can achieve global penetration even in low- and middle-income countries and socially complex settings. As a vaccine model for opioid overdose advances, stakeholders should assess and reflect on the factors and processes that may affect distribution and implementation in the context of various target groups and strive for equitable access and consistent messaging. The complex challenge of substance use requires creative approaches and opioid vaccines are a particularly promising one.

Responses