Periodic cooking of eggs

Introduction

Eggs are one of the most valuable foods1 on the tables of consumers and in the kitchens of chefs due to their abundant functional properties that make them the funniest and most versatile ingredients to work with. In fact, not only do they contain almost all essential nutrients2, which is fundamental for human nutrition3,4, but they are also distinguished by their excellent foaming and emulsification capacity and their ability to coagulate and form gels upon heating1,5.

As a consequence, they are commonly added in a variety of recipes, but are also used alone, and extremely different products can be obtained by changing the conditions under which they are cooked. In fact, tens of cooking methods are available today, including the most basic shell-on egg cooking techniques, of which à la coque, hard-boiling and soft-boiling are only the tip of the iceberg. In particular, the interest of chefs is currently attracted by the so called sous vide egg or 6X °C egg. This novel cooking method requires immersion of the shell-on egg in water at low and constant temperatures, usually between 60 and 70 °C, for at least 1 h6, and gives a very peculiar result, where both albumen and yolk have the same creamy texture.

The problem is that with this cooking technique, the albumen does not fully set (only one albumen protein is capable of doing so at such low temperatures, ovotransferrin7). Due to the fact that albumen and yolk have two very different compositions4,8,9, they require two different temperatures for optimal cooking, namely around 85 °C for albumen and around 65 °C for yolk5,6,10. Many chefs have tried to overcome this problem by cooking yolk and albumen separately at the appropriate corresponding temperatures, but this results in a series of too long and complicated steps.

As a response to this, we explore the idea of imposing two different cooking temperatures in two different regions of the egg without necessarily cracking the shell open. The inspiration comes from previous works of our group, where time-varying boundary conditions (BCs) in the mass transport of the blowing agent are exploited to produce foams with different layers in terms of morphology and/or density11. This same principle can also be exploited to obtain a desired thermal profile inside any material, eggs included. Therefore, we propose here to cook the egg by imposing a periodic time-varying BC in the energy transport problem to build our ad hoc thermal profile and repeat it until optimal cooking of both yolk and albumen. On a practical level, the idea is to place the raw shell-on egg alternatively in hot water (Th) and cold water (Tc) for relatively short periods of time (th and tc, respectively) and repeat these cycles N times until the cooking of both the yolk and the albumen is reached.

In the present article, design of the novel cooking method, namely periodic cooking, is conducted through mathematical modeling of the process, involving concomitantly heat transfer inside the egg and gelation of both egg yolk and albumen. A fine solution of the problem is then found through simulation with a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software, where imposition of different BCs allows to compare the evolution of the temperatures and the cooking degrees inside the egg obtained with different cooking methods (we will specifically refer to hard-boiling, soft-boiling, sous vide cooking and periodic cooking). Finally, validation of the simulation is allowed by cooking intact fresh eggs with all four methods and analyzing the final cooked products through both Sensory Analysis and Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) to gather information about color, consistency, texture, and taste. Additional information are then collected also through FT-IR spectroscopy, hydrogen-1 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H-NMR) and High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) in order to assess the extent of protein thermal denaturation and to analyze the nutritional profile of the eggs, respectively.

Overall, we found that our cooking method leads to improved texture and nutritional content with respect to traditional shell-on egg cooking techniques, thus elevating the already established concept by which temperature and time have a critical role in the resulting properties of egg parts. The potential of this approach beyond cooking, with possible uses in curing, crystallization, and material structuring, is also foreseen.

Results and discussion

Cooking simulations

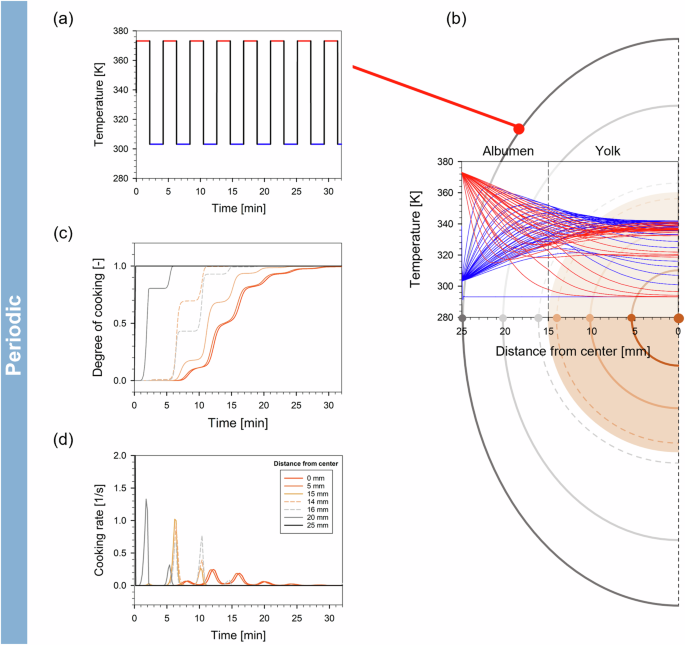

Results of the simulation of the cooking of an egg are here shown. Four different cooking techniques were simulated: periodic cooking (Fig. 1), hard-boiling (Fig. 2a, b), soft-boiling (Fig. 2c, d) and sous vide cooking (Fig. 2e, f). For all cooking techniques we show the evolution of the thermal profile over time and distance from the center of the egg, and the evolution of the degree of cooking over time and distance from the center of the egg.

Results of the simulation of the cooking of an egg with the periodic cooking method: a periodic time-varying BC imposed, b evolution of the thermal profile over time, c evolution of the degree of cooking over time at different distances from the center of the egg and d evolution of the cooking rate over time at different distances from the center of the egg. The distances from the center selected to construct the graphs of figures c and d are identified by the lines in figure b. The precise legend for figures c and d is given only in figure d.

Results of the simulation of the hard-boiling (red), soft-boiling (yellow) and sous vide cooking (green) of an egg: a, c, e temperature values over time at different distances from the center of the egg; b, d, f degree of cooking values over time at different distances from the center of the egg. The distances selected to construct these graphs are identified by the lines in Fig. 1b. The precise legend for all the figures a–f is given in figure a.

In the case of hard-boiled and soft-boiled eggs, the temperature grows monotonically over time (Fig. 2a, c). The different cooking time (12 min vs. 6 min, respectively), though, causes differences in the final thermal profile: hard-boiled eggs are at 100 °C in all their parts at the end of the 12 min cooking, while soft-boiled eggs show a lower and non-uniform temperature in almost all their parts at the end of the 6 min cooking, except for the parts adjacent to the shell. This different cooking time also causes a different cooking degree: in hard-boiled eggs the cooking degree reaches the unit in both albumen and yolk (Fig. 2b), while in soft-boiled eggs this happens only in the albumen. On the other hand, in the yolk the cooking degree remains lower, down to a minimum of 0.5 in the center of the egg (Fig. 2d). This is compatible with the cooking outcome of hard-boiling and soft-boiling, since soft-boiled eggs typically show a much runnier yolk compared to hard-boiled eggs.

Similar results were found for the sous vide egg in terms of the evolution of temperature over time (Fig. 2e): it grows monotonically until a plateau is reached at 65 °C in all parts of the egg. Nevertheless, the use of a lower cooking temperature causes differences in the final degree of cooking (Fig. 2f): unit is reached inside the yolk, but not inside the albumen, because the egg albumen proteins do not denature and aggregate at such low temperatures. This effect is visible in the simulation thanks to the kinetics equation that we used to model the gelation process.

Very different but satisfying results are obtained from the simulation of the periodic cooking technique (Fig. 1). As expected, temperature inside the egg does not grow monotonically, in accordance with the imposed BC, but a stationary state at the center of the yolk is reached as well (Fig. 1b): while the albumen alternatively sees temperatures in the range 100–87 °C and 30–55 °C during the hot and cold cycles respectively, the yolk sees a constant temperature of 67 °C, which is around the mean value between Th and Tc, as predicted. This peculiar thermal profile allows for optimal cooking of the egg in all its parts, and this is confirmed by Fig. 1c in which it is clear that a degree of cooking equal to 1 is reached both in egg yolk and albumen, differently from what happens with the sous vide cooking.

Finally, Fig. 1d shows the evolution of the cooking rates in albumen and yolk. These curves present various peaks over time at all distances from the center, which are clearly linked to the BC imposed: during the cold cycles (T = Tc), interruption of the cooking causes the cooking rate to be equal to zero. A final plateau of null cooking rate is eventually reached everywhere when the cooking degree reaches the unit, and this happens at different times depending on the distance from the center. In the case of hard-boiling, no such peaks are detected, but an equal plateau of null cooking rate is reached when the cooking degree reaches the unit, coherently with the BC imposed. A similar evolution of the cooking rate is expected for all other cooking techniques using a constant BC (soft-boiling and sous vide). Details are shown in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Section A.2 – Cooking simulations, Supplementary Fig. A2).

FT-IR spectroscopic analysis

FT-IR spectroscopy was performed on raw and cooked eggs to verify protein thermal denaturation and aggregation, which knowingly leads to thickening and gelling12. IR spectra collected for raw egg albumen and yolk are presented in Fig. 3a. Here, functional groups of lipids, proteins and water components can be detected. The complete list is given in Table 1.

a IR spectra of raw egg albumen (light gray) and yolk (orange) over the whole IR range (4000–650 cm−1). b Cooking index derived through the FT-IR spectroscopic analysis for all cooking techniques in the case of egg albumen and yolk. The different colors of the bars evidence the different cooking methods: hard-boiling (red), soft-boiling (yellow), sous vide cooking (green) and periodic cooking (blue). c IR spectra of raw and hard-boiled albumen (light and dark gray, respectively) and (e) of raw and hard-boiled yolk (orange and red, respectively) over the whole IR range. A close up on band no. 4 and 5 (amide I region) is displayed for both albumen (d) and yolk (f) with addition of the difference spectrum magnified ×5 (purple) and the baseline used for area quantification in the Amide I region (black dashed line). The purple arrow indicates in both cases the appearance of the aggregation band.

Bands no. 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9 and 10 are associated with functional groups of the lipid component. These can be easily detected in the yolk spectrum, while they are not present in the albumen spectrum because egg albumen does not contain fats. Bands no. 5 and 6 represent the amide I and amide II region, respectively. They are attributed to the secondary structure of proteins and they are visible in the spectra of both egg phases, since proteins are present in both albumen and yolk. Finally, band no. 1 is the water band and has a wide range in the spectra of both albumen and yolk.

Amongst these, the amide I region (band no. 5), more resolved in the IR range with respect to the amide II region, is the most important region in our study, because it has a huge potential to give information on the secondary structure of egg proteins. The band at 1636 cm−1, in particular, is the most relevant because it is characteristic of the amide groups involved in the β-sheet structure, which in turn are linked to the denaturation of the proteins: an increase in the β-sheet structure at the sacrifice of the helical structure is interpreted as a result of heat denaturation5. It is noted that in some works the characteristic frequency of intermolecular β-sheets is found at 1620 cm−1 4,10. In general, the evaluation of the band at 1636/1620 cm−1, often called “aggregation band”, is a good diagnostic tool for monitoring thermal unfolding of the proteins. It is in our interest, then, to see how the aggregation band changes with different cooking methods, so that we can understand how different cooking methods can affect the level of protein unfolding, i.e., protein denaturation and aggregation and consequent egg texture.

An example of the outcome of such measurement in the specific case of hard-boiled egg yolk and albumen is shown in Fig. 3c, e, completed with a close up on the regions of interest and the corresponding difference spectrum (purple) (Fig. 3d, f). The appearance of the aggregation band, indicating β-sheet formation, is highlighted in both cases with a purple arrow. Details on all the IR spectra collected (egg albumen and yolk cooked with all the different cooking techniques) can be found in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Section A.2 – FT-IR spectra, Supplementary Figs. A3–A10).

From these spectra, evaluation of a Cooking index, according to the procedure described in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Section A.1 – Analysis of FT-IR spectra), was possible and this helped understand the different extent of protein denaturation with the different cooking techniques. Results are shown in Fig. 3b for both yolk and albumen.

In the case of yolk, the Cooking index is maximum for hard-boiling (as imposed), followed by, in order, sous vide, soft-boiling and periodic cooking. This is linked to the type of thermal treatment and matches the different textures and consistencies of the cooked products: hard-boiled egg yolk is a solid paste, while sous vide, soft-boiled and periodic egg yolks are gel-like substances with an increasing tendency to flow.

In the case of albumen, the Cooking index is maximum for hard-boiling, followed by, in order, soft-boiling, periodic cooking and the sous vide. Again, this is linked to the type of thermal treatment and matches the different textures: hard-boiled egg yolk is fully set, while this isn’t true for soft-boiled, periodic and sous vide. The sous vide albumen, in particular, is completely runny and cooking appears to be not sufficient due to lack of reaching the appropriate albumen cooking temperature (85 °C). This problem appears to be overcome with the periodic cooking technique because the use of the cycles helps to reach a higher temperature in the albumen, allowing for further cooking and setting, while still maintaining the creamy consistency of the yolk. This detail is what makes it possible to have a runny, creamy yolk with a nicely set albumen when using the periodic cooking technique, differently from what happens with other cooking methods. In other words, spectroscopy confirms the simulation results.

Quantitative descriptive analysis

The quantitative descriptive analysis is an objective sensory analysis that allows to define with greater accuracy and detail, with respect to what the consumer is able to do, the sensory profile of a product. Results of this analysis are shown in Fig. 4, where specific significant differences are highlighted.

a Photographs of the raw, hard-boiled (red), soft-boiled (yellow), sous vide (green) and periodic (blue) eggs. Results of the Sensory Analysis performed on b albumen and c yolk. Significant differences (p = 95%) are identified between: hard-boiled and periodic yolk (in Astringency, Softness, Wetness, Meltability, Sweetness and Umami); soft-boiled and periodic yolk (in Shininess, Wetness and Sweetness); sous vide and periodic yolk (in Shininess, White color, Softness, Wetness and Meltability); hard-boiled and periodic albumen (in Shininess, Orange color, Density/body, Wetness, Solubility, Pastiness, Adhesiveness, Powderiness, Sweetness and Umami); soft-boiled and periodic albumen (in Density/Body, Wetness, Sweetness and Saltiness). No significant differences are found between sous vide and periodic yolk.

As it is visible, the main differences between the 4 different products concern not only texture-related properties, but also several characteristics related to taste area.

Compared to the periodic, both the albumen and yolk of the hard boiled sample differ mainly for its less wet, more adhesive and more powdery/sandy consistency when pressed between tongue and palate. When analyzing the taste, the egg albumen is sweeter and more stringent, the yolk is less sweet and both egg albumen and yolk have less umami taste (although it is perceived at a weak intensity).

The soft boiled sample, differently from the periodic, has a shinier/brighter surface of the albumen and it is drier in the mouth and less sweet. The yolk is less dense/bodied and wetter, less sweet as well as less salty.

Finally, compared to the periodic sample, the sous vide albumen is shinier and clearer/transparent. It is also definitely softer, wetter and more soluble during tasting. On the other hand, the yolks are very similar to each other and no significant differences emerge.

In conclusion, the periodic egg is more similar to the soft boiled when analyzing the texture of its albumen, while it is very similar to the sous vide sample when considering its yolk. This confirms the effectiveness of periodic cooking in delivering two very different textures and tastes in the egg albumen and yolk, respectively: the yolk is most similar to that cooked at a constant temperature of 65 °C, while the albumen is most similar to that cooked at 100 °C, in full agreement to simulation results and expectations.

Texture profile analysis

TPA parameters of both egg albumen and yolk are presented in Table 2. In general terms, the biggest differences are found in hardness (also displayed in the box plot of Fig. 5) and chewiness (or gumminess).

Hardness evaluated through TPA for albumen and yolk. The color legend is the same of Fig. 4 and indicates the different cooking techniques: hard-boiled (red), soft-boiled (yellow), sous vide (green) and periodic (blue). Each box of the box plot displays (bottom to top) minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum.

In the albumen, hardness is higher in the hard-boiled sample and progressively decreases in the soft-boiled, sous vide and periodic samples, while chewiness is higher in the hard-boiled and soft-boiled samples, and progressively decreases in the periodic and, most significantly, in the sous vide sample. This is consistent with the results of the sensory evaluation, which shows the same trend in the values of softness, wetness and meltability.

In the yolk, hardness is higher in the hard boiled-sample and progressively decreases in the periodic, soft-boiled and sous vide samples, while chewiness (here partially gumminess because most of the samples are semi-solids) is higher in the hard-boiled sample and progressively decreases in the soft-boiled, periodic and sous vide samples, the latter bearing more similarities with each other. Again, this is consistent with the results of the sensory evaluation, which shows that the highest difference in terms of texture (density/body, wetness, solubility, pastiness, adhesiveness, powderiness) is found in the hard boiled sample, while the remaining are more similar to each other.

Overall, TPA confirms that different cooking methods are able to deliver different textures, but, unlike the sensory analysis, it is less capable of highlighting specific differences between the soft-boiled, sous vide and periodic samples probably due to sampling complexity.

1H-NMR and UHPLC Q-Orbitrap HRMS based analyses

To evaluate the effect of the various cooking methodologies proposed in this study on the nutritional profile of the eggs, an untargeted study has been performed on the albumens and yolks by using 1H-NMR spectroscopy. The samples were prepared and the spectroscopic data processed as described in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Section A.1). All the NMR spectra were analyzed by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to specifically explore the differences in albumens and yolks across the investigated class. The primary purpose of PCA is to reduce the complexity of a dataset containing many interrelated variables, allowing for a visual representation of the main sources of variance in the data. PCA achieves this by transforming the original correlated variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated variables called principal components (PCs). These PCs form the axes of a new coordinate system, with the first principal component (PC1) representing the highest variance, the second (PC2) representing the next highest, and so on. PCA results are typically displayed in two types of plots: a “scores plot”, which shows groups samples based on their similarity, and a “loadings plot”, which highlights the variables that contribute to the differences between samples along each principal component. In this study, however, PCA results are presented using a biplot (Fig. 6), which combines the scores plot and the loadings plot into one. This approach facilitates the visualization of both samples and variables within a single plot, improving interpretability. Notably, PCA biplot of the 1H-NMR-based metabolomic data (Fig. 6a) revealed that, consistent with previous works, PC1, accounting for 84.31% of the total variation, clearly distinguished yolks from albumens13. In addition, the distribution of the variables on the PCA biplot suggested that most of the detected amino acids were more abundant in the yolk compared to the albumen (left side of the PCA biplot reported in Fig. 6a). Conversely, albumens were richer in formate and sugars (right side of the PCA biplot reported in Fig. 6a).

PC1 vs. PC2 biplot of the PCA model calculated using (a) both albumen and yolk extracts analyzed by 1H-NMR and (b) yolk extracts analyzed by MS analysis and spectrophotometric assays. Acronyms used in the graphs are reported in Table 3.

Among yolk amino acids there are leucine (Leu), isoleucine (Ile) and valine (Val), known as branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). BCAAs, which are primarily metabolized in brain, kidney and muscle, can provide nitrogen groups for the nitrogen-containing substances biosynthesis (e.g. creatinine, creatine, glutathione, pyridine and carnitine) and are recognized as gluconeogenic amino acids, providing a source of glucose14. Moreover, isoleucine can promote myogenesis and intramyocellular fat deposition, thereby increasing muscle mass15. BCAAs also play a crucial role in psychological disorders, with studies showing an inverse relationship between dietary BCAAs and the likelihood of depression and anxiety16.

Concerning albumen composition, it’s worth to notice that lysine is an essential amino acid involved in the synthesis of crucial proteins such as nucleoproteins, and hemoglobin. Lysine (Lys) also promotes bone growth and development in children enhancing calcium absorption and increasing appetite17. In addition, albumens are richer in tryptophan, an essential amino acid that cannot be synthesized by living organisms and needs to be obtained from daily diet. Tryptophan, an aromatic amino acid, is key element for brain functioning, due to its role as a precursor for the neurotransmitter serotonin. Lower levels of tryptophan are often associate with depressive mood18. Therefore, the consumption of both egg yolk and albumen can provide more energy and may help prevent brain diseases19.

Interestingly, PC2 (12.02% of total variance) shows a separation of the egg samples according to the cooking method (Fig. 6a). Specifically, both the yolks and albumens cooked using the periodic method (blue samples) are positioned in the upper part of the plot, well separated from the samples cooked using other methods. This suggests that the periodic cooking approach affects the egg metabolome in a peculiar way, deserving further investigation through Mass Spectrometry (MS)-based analysis. Particularly, we decided to quantify polyphenols and amino acids only in the yolk, which is known to contain the vital nutrients that characterize the egg.

The PCA model obtained with the UHPLC Q-Orbitrap HRMS data is reported in Fig. 6b.

Excitingly, the PCA biplot showed that the separation between the periodic and all the remaining groups is even more pronounced compared to that observed in the NMR-based analysis. Interestingly, the periodic yolk group is characterized by higher content of all the investigated polyphenols (the most abundant and broadly distributed class of bioactive molecules) compared to the other samples. The association between polyphenol consumption and human health has been explored20, and it has been observed that a diet rich in polyphenols appears to be protective and prevent the onset of several diseases. Particularly, flavonoids are the main class of polyphenols in the analyzed extracts. It’s worth to notice that among the detected flavonoids there is an isoflavone named daidzein, whose concentration in eggs depends on the diet of laying hens. It is also used as a dietary supplement for laying hens. This compound has gained popularity as a dietary supplement, especially for animals in the post-estrogenic period, offering a natural and safe alternative to estrogen-like compounds21. Liu et al.22 assessed that daidzein improved egg quality by controlling lipid metabolism in layers and enhancing the antioxidant capacity of egg yolks. Moreover, isoflavones like daidzein are biologically active compounds with estrogenic properties, that may have a modest beneficial effect for human health, particularly on menopausal symptoms and may reduce the incidence of prostate and breast cancer20. In addition, the investigation identified also the presence of some phenolic acids among the extracts’ polyphenols, such as the ferulic and chlorogenic acid.

Overall, these results strongly suggest that the periodic cooking method have a better advantage over conventional cooking methods in terms of nutritional content.

Conclusions

It appears that the design of the novel cooking method, namely periodic cooking, was carried out successfully. Designing of the process and subsequent simulation proved fundamental in the understanding of the physics behind the cooking of an egg and allowed us to finely tune the process parameters with respect to our objective, i.e., having two different, optimal, temperatures in the two phases of the egg. Simulated results proved to be consistent with the results of cooking experiments, and the FT-IR spectra measurements corroborated them, proving the different extent of protein denaturation (and consequent thickening and gelation) with different cooking methods (namely, hard-boiling, soft-boiling, sous vide and periodic cooking). Analysis of the color, texture, and consistency of all the egg products was only the final proof of a successful cooking experiment that might inspire new fancy recipes, proving how knowledge of the science behind simple problems can improve even the slightest bits of our daily life, like the simple act of eating an egg. Studying the nutritional profile of such eggs only helped validating this final statement, as periodic cooking clearly stood out as the most advantageous cooking method in terms of egg nutritional content. An even higher impact on human diet is here implied: not only we are able to reach a perfectly diverse texture in a two-phase food product, but we are also able to preserve, in both these phases, a higher nutrient amount, providing a useful tool to boost poor dietary habits. The possibility of exploiting this process outside the kitchen realm is also foreseen: curing, crystallization, and structuring of materials are only a few of the applications for which a thoroughly designed periodic thermal treatment is at hand.

Materials and methods

Materials

Fresh hen eggs were purchased at a local supermarket (Naples, Italy) and stored at room temperature in a cool and dry place. These were used for all experiments except for Sensory Analysis. Fresh hen eggs for the Sensory Analysis were provided by Ovomont S.r.l., Castelvetere sul Calore (AV), Italy.

Methods

Egg cooking methods

Cooking experiments of shell-on eggs were performed with a heater and a kitchen pan. The pan was filled with tap water and placed on the heater to reach the boiling or the desired temperature. Constant monitoring of the water temperature was possible thanks to a food thermometer, which was immersed in water as the cooking proceeded. Four different cooking techniques were tested, namely hard-boiling, soft-boiling, sous vide or 6X °C and periodic cooking. Hard-boiled eggs were placed in boiling water for 12 min; soft-boiled eggs were placed in boiling water for 6 minutes; sous vide eggs were placed in water at 65 °C for 1 h and periodic eggs were placed alternatively in boiling water (Th = 100 °C) for th = 2 min and water at Tc = 30 °C for tc = 2 min, for a total cooking time of 32 minutes, which corresponds to the repetition of the hot and cold cycles for a total of N = 8 times. In the case of periodic eggs, a bowl filled with water kept at 30 °C was used for the cold cooking cycle.

After each cooking experiment, the eggs were cooled down under running water and then the shell was cracked open. Pictures of a cross section of each egg were taken (See Fig. 4a).

Mathematical modeling and simulation

To model the heat transfer phenomenon and concomitant thickening and gelling of egg yolk and albumen during cooking of the egg in hot water, the following assumptions were made:

-

1.

Egg albumen and yolk are homogeneous and isotropic during cooking;

-

2.

The initial temperature is constant and the same in all eggs (T = 20 °C);

-

3.

Thermal conductivity and density of both egg phases are a function of temperature;

-

4.

Presence of an air cell, natural convection and moisture transfer inside the egg are neglected.

The derived model is here presented:

Equation (1) is the conduction only energy transfer equation, while Eq. (2), coupled with it, describes the evolution of the degree of cooking X(t) over time. Ri represents the gelation rate and is thus expressed:

Where ρi, ({c}_{{p}_{i}}) and ki are the thermal properties of egg yolk and albumen and (frac{1}{{tau }_{i}}={A}_{i}{e}^{frac{-{E}_{{a}_{i}}}{R{T}_{i}}}) is the rate constant of the gelation process, whose dependence on the absolute temperature is given by the Arrhenius equation, Ai and ({E}_{{a}_{i}}) being the pre-exponential factor and the activation energy, respectively. More specifically, all the parameters used in the system, both thermal properties and kinetics data, are listed and explained in Table 4. It is evident that two different sets of parameters are used for the yolk and the albumen, respectively. This is due to their different composition and the different denaturation processes happening in the two phases.

From a quick analysis of this system we are able to provide an estimate of the parameters of our cooking method. From the values of thermal conductivity, specific heat and density, we can find, for both albumen and yolk, thermal diffusivities ({a}_{i}={{{{mathcal{O}}}}}(1{0}^{-5},{m}^{2}{s}^{-1})), and, considering a length scale (L={{{{mathcal{O}}}}}(1{0}^{-2},m)), the characteristic time for heat transport ({{{{mathcal{O}}}}}(1{0}^{1},s)), which gives us an idea of th and tc. Th is the optimal cooking temperature for the albumen, while Tc is chosen such that the mean between these two values is the optimal cooking temperature for the yolk (in case th = tc). Finally, the number of cycles N is related to the kinetic constants, being the largest between (frac{{tau }_{yolk}}{{t}_{h}}) and (frac{2cdot {tau }_{albumen}}{{t}_{h}}). A first design of the novel cooking method was made exploiting these considerations.

Simulation with a CFD program was then used for a finer resolution of the problem for all the cooking techniques previously listed (hard-boiling, soft-boiling, sous vide and periodic cooking). The geometry of the egg was designed as a 2D axisymmetric oval with 7 and 5 cm axis and with a sphere (radius 1.5 cm) in the geometric center as the yolk. The mesh was Mapped at the edges, where higher changes are expected, and Free triangular elsewhere. Initial conditions were Xi(t = 0) = 0 and T(t = 0) = 20 °C for all simulations. As for the BCs, a no flux condition was imposed in all simulations, while three different BCs were used on temperature to be able to simulate all the cooking techniques (T = 100 °C for hard-boiling and soft-boiling, T = 65 °C for sous vide cooking and Fig. 1a for periodic cooking).

The system of differential equation was solved by the “finite element” method in the “Direct UMFPACK” mode at time intervals of 0.5 min. The total process time was 12 min for hard-boiled eggs, 6 min for soft-boiled eggs, 1 h for sous vide eggs and 32 min for periodic eggs.

This simulation can be easily adapted to the variations in the quality and size of the egg. An estimation of the corresponding changes is quickly given by the scaling arguments mentioned above: the characteristic time for heat transport (L2/a) expresses the relationship with the characteristic dimension of the object (L), while Th, Tc and the kinetic constants express the relationship with egg quality.

Characterization techniques

To characterize the cooked products obtained with all the cooking methods hereby examined (hard-boiling, soft-boiling, sous vide cooking and periodic cooking), we have used a series of characterization techniques, here mentioned:

-

FT-IR spectroscopy, to assess the extent of protein denaturation;

-

TPA, to gather information on the texture of egg albumen and yolk;

-

Quantitative Descriptive Analysis, to get insights on color, consistency, texture and taste of the cooked products;

-

Metabolomic Analysis (specifically 1H-NMR and HRMS), to investigate the nutritional profile of the eggs.

Moreover, we also carefully verified that in periodic cooking the thermal load was sufficient to avoid microbiological issues. All the details about the characterization techniques and the microbiological considerations can be found in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Subsection A.1).

Responses