Influenza B viruses are more susceptible to high temperatures than influenza A viruses

Introduction

Seasonal influenza is a respiratory infection caused by seasonal influenza viruses. When seasonal influenza A and B viruses infect humans, they generally cause symptoms such as fever over 38 °C, headache, muscle aches, and joint pain. Influenza symptoms usually last for a short time (3–5 days), but the infection can sometimes become severe with bronchitis, pneumonia, and other complications1. Prior to COVID-19, seasonal influenza viruses infected 5%–15% of the world’s population each year, causing severe illness in 3–5 million people and respiratory-related deaths in 290,000–650,000 people (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal)). During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the number of influenza cases declined sharply compared to previous years. Since the 2022–2023 season (i.e., towards the end of the COVID-19 pandemic), the number of influenza cases has returned to previous levels in Japan2, and influenza has once again become a major public health concern, including the threat of a concurrent epidemic of COVID-19 and influenza.

Seasonal influenza is attributed to two types of influenza virus, influenza A and B viruses. The primary natural reservoir of most of Influenza A viruses is wild aquatic birds, whereas humans are considered as primary natural host of influenza B viruses. Influenza A viruses are further classified into subtypes according to the combination of haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) glycoproteins on their viral surface. Currently, 18 HA subtypes and 11 NA subtypes of influenza A viruses are known3 and most subtypes of influenza A virus rarely infect humans. Of the known subtypes, two (A/H1N1 and A/H3N2) are currently circulating as seasonal influenza viruses. In the case of influenza B viruses, currently, two lineages (B/Victoria-lineage and B/Yamagata-lineage), which diverged in the 1970s, are circulating as seasonal influenza viruses4,5. The epidemiologic spread of influenza A and B viruses is not uniform, with infections by each virus peaking at different times during the season6,7,8. This may reflect differences in the characteristics of each virus; however, differences between the influenza A and B viruses that are circulating among humans have not yet been fully elucidated.

In general, viruses replicate efficiently at an optimum temperature. Seasonal influenza A and B viruses target the epithelial cells of the human upper respiratory tract, where the temperature is around 33 °C9,10. Therefore, it is generally accepted that seasonal influenza viruses replicate efficiently at 33 °C. Yet, the susceptibility of seasonal influenza viruses to high temperature conditions observed during fever, and whether there is a difference is such susceptibility between influenza A and B viruses, has not been fully explored. In this study, we investigated the sensitivity of seasonal influenza A and B viruses to the high temperature condition observed during fever (i.e., 39 °C).

Results

Incubation of seasonal influenza viruses at high temperature decreases their infectivity

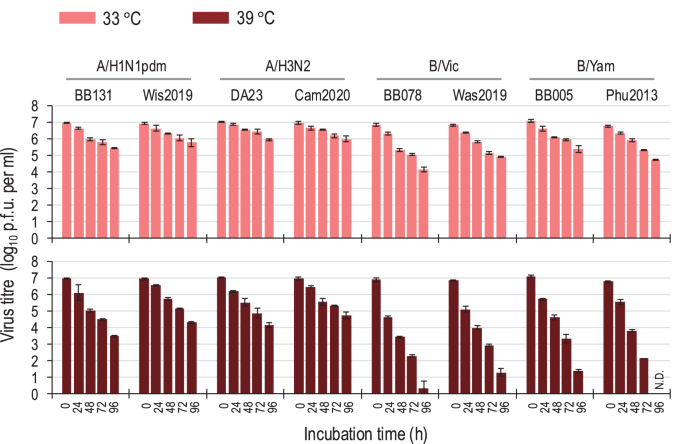

To examine the effect of temperature on the infectivity of seasonal influenza viruses, we incubated 107 plaque forming unit (PFU) of influenza A and B viruses at different temperatures (33 °C or 39 °C) for different times (24, 48, 72, and 96 h), and then measured the infectivity of the incubated viruses by using hCK, humanized Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells11, which are genetically modified MDCK cells that express glycans with elevated levels of sialic acid in α2,6-linkages that are recognized by human influenza viruses (Fig. 1). In this study, we tested two A/H1N1 2009 pandemic (A/H1N1pdm) viruses [A/Tokyo/UT-BB131/2017(H1N1pdm; BB131(A/H1N1pdm)) and A/Wisconsin/588/2019 (H1N1pdm; Wis2019(A/H1N1pdm))], two A/H3N2 viruses [A/Tokyo/UT-DA23-1/2017(H3N2; DA23(A/H3N2)) and A/Cambodia/E0826360/2020 (H3N2; Cam2020(A/H3N2))], two B/Victoria lineage viruses [B/Tokyo/UT-BB078/2017(Victoria; BB078(B/Vic) and B/Washington/02/2019 (Victoria; Was2019(B/Vic)], and two B/Yamagata lineage viruses [B/Tokyo/UT-BB005/2017(Yamagata; BB005(B/Yam)) and B/Phuket/3073/2013 (Yamagata; Phu2013(B/Yam))]. When the viruses were incubated at 33 °C for 96 h, the infectivity titres of the four influenza A viruses were 0.97–1.51 log units lower than the starting titres (107 PFU); similarly, the infectivity titres of the four influenza B viruses were 1.72–2.72 log units lower than the starting titres (Fig. 1). In contrast, when the viruses were incubated at 39 °C for 96 h, the infectivity titres of the influenza A viruses were 2.23–3.51 log units lower and those of the influenza B viruses were 5.52–6.77 log unit lower than the titres of the viruses that were not incubated at the higher temperature (Fig. 1). These results suggest that high temperature significantly decreases the infectivity of influenza B viruses compared to that of influenza A viruses.

Aliquots of virus stock containing 107 PFU/ml units were incubated for the times indicated at 33 °C or 39 °C. Virus titres in the incubated samples were determined by performing plaque assays on hCK cells at 37 °C. Each point represents the mean ± standard deviation from triplicate experiments. N.D. infectious virus was not detected.

High temperature has a greater effect on the replication efficiency of influenza B viruses than on that of influenza A viruses

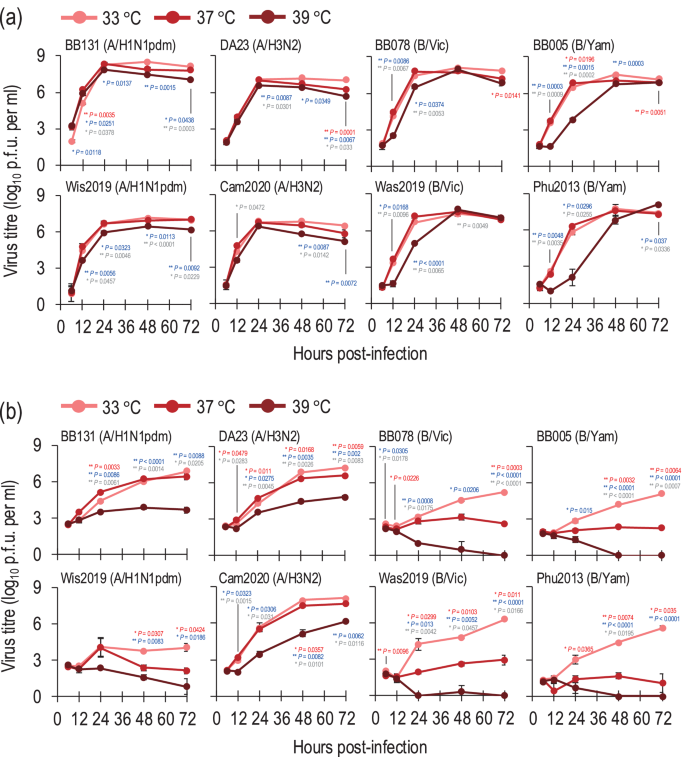

Next, to investigate whether temperature affects the replicative ability of seasonal influenza A and B viruses, we examined their growth kinetics in hCK cells at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, and 39 °C). In hCK cells, the four influenza A viruses (i.e., two A/H1N1pdm and two A/H3N2 viruses) grew well at all temperatures tested although the titres of these viruses at 39 °C were slightly lower than those at 33 °C (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the four influenza B viruses (i.e., two B/Victoria and two B/Yamagata viruses) grew much slower and to lower titres (0.96–3.72 log units lower at 24 h post-infection) at 39 °C than at 33 °C (Fig. 2a).

Growth kinetics of seasonal influenza viruses in hCK (a) and A549 (b) cells at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, or 39 °C). hCK cells or A549 cells were infected with seasonal influenza viruses at an MOI of 0.01 at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, or 39 °C). The supernatants of the infected cells were harvested at the indicated times, and the virus titres were determined by performing plaque assays in hCK cells. Data are shown as the mean of triplicate experiments. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. Mean values were compared by using a two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). Red and blue asterisks indicate the comparison at 37 °C and at 39 °C with at 33 °C, respectively; grey asterisks indicate the comparison between 37 °C and 39 °C.

We also examined the growth kinetics of these influenza A and B viruses in a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (A549 cells) at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, and 39 °C). In A549 cells, the BB131(A/H1N1pdm), DA23(A/H3N2) and Cam2020(A/H3N2) viruses grew efficiently at 33 °C and 37 °C, although slight differences in viral titres were observed at some timepoints (Fig. 2b). At 39 °C, the BB131(A/H1N1pdm), DA23(A/H3N2) and Cam2020(A/H3N2) viruses replicated less efficiently compared to at 33 °C and 37 °C (Fig. 2b) although the titre of Cam2020(A/H3N2) reached 1.45 × 106 PFU after 72 h post-infection. The Wis2019(A/H1N1pdm) virus replicated poorly at all temperatures. The influenza B viruses propagated less efficiently in A549 cells than in hCK cells. The B/Victoria and B/Yamagata viruses grew more slowly and to lower titres (1.39–2.77 log units lower at 48 h post-infection) at 37 °C than at 33 °C (Fig. 2b). Strikingly, all four influenza B viruses failed to replicate in A549 cells at 39 °C (Fig. 2b). In addition, we assessed the effect of temperature on a single cycle of virus growth in A549 cells. The BB131(A/H1N1pdm), DA23(A/H3N2), BB078(B/Vic), and BB005(B/Yam) viruses were selected to represent each subtype and lineage, and each virus was inoculated into A549 cells at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, and 39 °C) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. The virus titres of BB131(A/H1N1pdm) and DA23(A/H3N2) at 16 h post-infection at 39 °C were 2.82 × 106 PFU and 5.4 × 105 PFU, respectively, which were lower than those at 37 °C but similar to those at 33 °C (Supplementary Fig. 1). In contrast, no replication of influenza B viruses was observed at 39 °C (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting high temperature cannot support a single cycle of replication of influenza B viruses in A549 cells.

We also examined whether temperature affects the plaque formation of seasonal influenza viruses. Plaque assays were performed for each stock virus at 33 °C, 37 °C, and 39 °C using hCK cells and the plaque counts were compared. No significant differences were observed between the number of plaques of influenza A viruses (i.e., BB131(A/H1N1pdm), Wis2019(A/H1N1pdm), DA23(A/H3N2) and Cam2020(A/H3N2)) cultured at 33 °C, 37 °C, and 39 °C (Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, the plaque counts for influenza B viruses [i.e., BB078(B/Vic), Was2019(B/Vic), BB005(B/Yam) and Phu2013(B/Yam)] were significantly lower when the infected cells were cultivated at 39 °C than at 33 °C or 37 °C (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Taken together, these data demonstrate that the replication efficiency of influenza B viruses is more affected than influenza A viruses by high temperature conditions.

The expression of influenza B virus HA protein capable of binding to turkey red blood cells is reduced on the surface of virus-infected cells cultivated at 39 °C

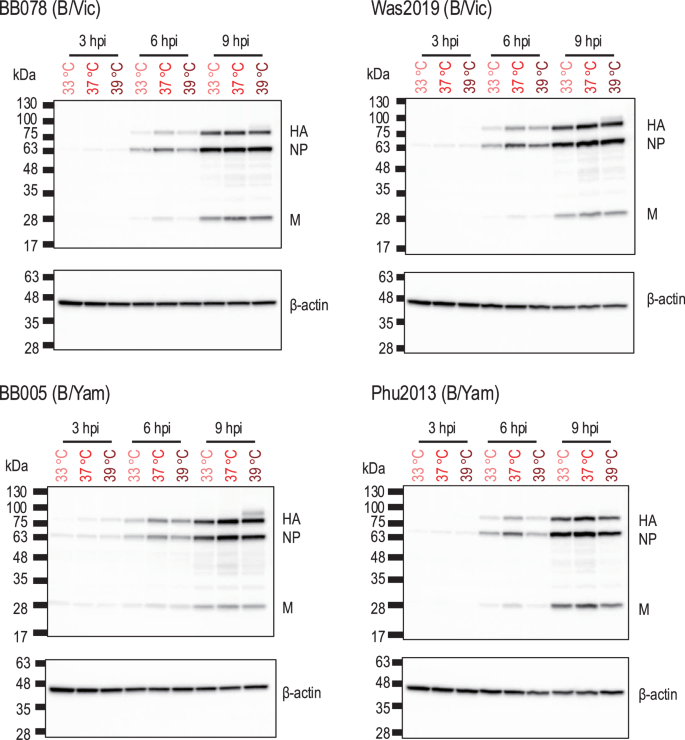

To assess which stage of the replication cycle of influenza B viruses is affected by high temperature, the expression levels of viral proteins in the virus-infected cells at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, or 39 °C) were compared. A549 cells were inoculated with influenza B viruses [i.e., BB078(B/Vic), Was2019(B/Vic), BB005(B/Yam) and Phu2013(B/Yam)] at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, and 39 °C) at an MOI of 5, and the viral proteins in the cell lysates at 3, 6, and 9 h post-infection were assessed. We found no significant differences in the expression levels of viral proteins (i.e., HA, NP, and M1) at all culture temperatures tested (Fig. 3). These results indicate that high temperature has no major effect on the early steps of the replication cycle (i.e., entry, genome replication/transcription, and translation) of influenza B viruses.

A549 cells were infected with viruses at an MOI of 5 at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, or 39 °C). The infected cells were collected at 3, 6, and 9 h post-infection, lysed in SDS loading buffer, and further analysed by Western blotting. Protein bands of HA, NP, and M as well as beta-actin were detected by Western blotting.

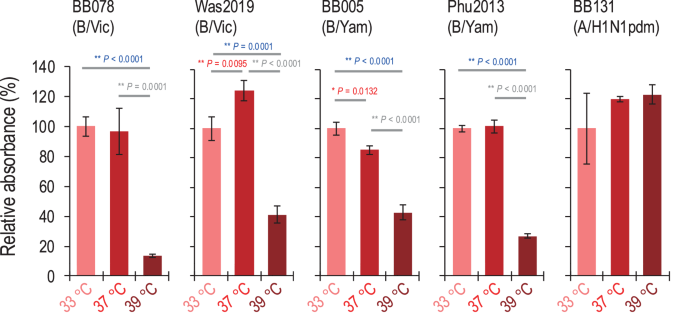

To investigate whether culture temperature affects the late stage of the influenza B virus life cycle, we examined the expression of viral glycoproteins (especially HA) on the surface of infected cells at different incubation temperatures. We performed haemadsorption assays using A549 cells infected with influenza B viruses [i.e., BB078(B/Vic), Was2019(B/Vic), BB005(B/Yam) and Phu2013(B/Yam)] at an MOI of 5 and cultured at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, or 39 °C). At 12 h post-infection, the infected cells were incubated with turkey red blood cells (TRBCs), and TRBC binding to HA-expressing cells was assessed by use of light microscopy. At all temperatures tested, the TRBCs bound to the infected cells, but the infected cells cultured at 39 °C bound to fewer TRBCs than those cultured at 33 °C or 37 °C (Supplementary Fig. 3). To quantify our findings, we measured the absorbance of the dissolved haemoglobin. The absorbance of the dissolved haemoglobin by the TRBCs bound to cells infected and cultured with influenza B viruses at 39 °C was significantly lower (13.6%–43.0%) than that at 33 °C or 37 °C (Fig. 4). For influenza A virus [i.e., BB131(A/H1N1pdm)], the TRBCs bound to infected cells cultured at 39 °C to the same extent as at 33 °C and 37 °C (Supplementary Fig. 3). Similarly, the absorbance of the dissolved haemoglobin by TRBCs bound to cells infected and cultured with BB131 (A/H1N1pdm) at 39 °C was not significant different from that at 33 °C or 37 °C (Fig. 4). These results suggest that high temperature decreases the expression of influenza B virus HA with the ability to adsorb with TRBCs on the cell surface of virus-infected cells.

A549 cells were infected with viruses at an MOI of 5 at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, or 39 °C). At 12 h post-infection, haemadsorption was measured by incubating the cells with 1% TRBCs at 4 °C for 1 h. For quantification, the absorbance of the dissolved haemoglobin was measured; absorbance at 33 °C is shown as the standard. Mean values were compared by using a two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

Discussion

Here, we found that the replication efficiency of both influenza A and influenza B viruses circulating among humans is reduced in A549 cells at an incubation temperature of 39 °C. There are several possible explanations for this, for example, the high temperature may affect the stability of the viral protein(s) and/or the functions of host factors (e.g., protein processing, intermolecular interactions, etc.) in virus-infected cells. Previous studies, which have mainly focused on influenza A viruses, have reported that the M1 of influenza A virus dissociates from viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs) and inhibits the nuclear export of vRNPs at 41 °C, thereby suppressing virus production in MDCK cells12. One of the molecular mechanisms involves HSP70, the expression of which increases at 41 °C, inhibiting the binding of M1 to vRNPs13. A previous report focusing on influenza B viruses that did not use actual viruses found that the HA protein of influenza B viruses is slightly downregulated at 39 °C14. Our data show that influenza B viruses are more susceptible than influenza A viruses to changes in their growth efficiency when cultured at 39 °C. Our findings also suggest that the expression of influenza B virus HA protein with receptor-binding activity is reduced on the surface of virus-infected cells cultured at 39 °C, which may have led to the decreased replication of influenza B virus. There are at least two possible explanations for why the high temperature condition resulted in the decreased expression of HA with receptor-binding activity on the cell surface: (1) the high temperature condition may cause a conformational change in HA that results in reduced receptor-binding activity, and (2) the high temperature condition may cause a decrease in the number of HA molecules on the cell surface. To test the former possibility, we evaluated the hemagglutination (HA) activity of influenza viruses after a 1 h incubation at different temperatures and found that incubation at 50 °C did not affect the HA activity of influenza B viruses (Supplementary information and Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that the high temperature condition had no effect on the receptor-binding activity of influenza B virus HA protein. Therefore, it is more likely that the high temperature condition led to a decrease in the number of HA molecules on the cell surface. Moreover, our preliminary data suggest that the high temperature condition may cause the aggregation and/or modification of the HA proteins of influenza B viruses, which could inhibit their intracellular transport, resulting in a decrease in the number of HA molecules on the cell surface (unpublished data). Further detailed studies are needed to clarify the molecular mechanism.

HA stability is an important determinant of the airborne transmission of influenza viruses15,16. A previous study using infectious viruses isolated from droplets released from influenza A virus-infected ferrets showed that viruses with mutations that destabilize HA proteins have reduced infectivity in air17. Another study, in which the evolution of the HA protein thermal stability of A/H1N1pdm and A/H3N2 viruses between 2009 and 2016 was computationally estimated, showed that the descendants of the viruses predicted to encode more stable HA proteins survived18. Heat treatment at neutral pH promotes irreversible fusion forms of HA proteins and inactivates the virus19,20, such that it can be used as an assay to evaluate HA stability21,22. In this study, we showed that after long-term incubation of influenza virus particles at high temperature (i.e., 39 °C), the infectious titres of both influenza A and influenza B viruses were significantly reduced, with a greater decrease in infectious titres being observed for influenza B viruses. Heat treatment at 39 °C may affect the stability of the HA protein, thereby reducing the efficiency of viral infection, and influenza B viruses may be more susceptible to this effect than influenza A viruses.

High fever is a most common symptom of seasonal influenza. Although, specific differences in fever symptoms caused by influenza A and B viruses have not been clearly demonstrated, there are reports that patients infected with A/H3N2 virus have higher fever than those infected with Soviet-type A/H1N1 or influenza B virus23. In addition, previous reports from antibody-free volunteers have shown that temperature-sensitive strains of influenza A viruses (i.e., those with shut-off temperatures below 38 °C, at which virus replication is significantly reduced) caused very mild symptoms, whereas wild-type strains (i.e., those with shut-off temperatures above 39 °C) were highly reactive (e.g., induced fever > 38.6 °C)24. Our results suggest that influenza B viruses are less likely to replicate at high fever temperature (i.e., 39 °C). Therefore, it is possible that high fever occurs less frequently in patients infected with influenza B viruses. To confirm this hypothesis, further clinical studies and in vivo-based experiments needed.

In summary, temperature sensitivity differs between influenza A and B viruses circulating among humans. The expression pattern of the HA protein of influenza B virus changes at 39 °C, and the decreased expression of influenza B virus functional HA protein with receptor-binding activity at the cell surface affects viral replication. Our study thus contributes to our understanding of the properties of seasonal influenza viruses.

Methods

Cells

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were maintained in Eagle’s MEM (Gibco) containing 5% newborn calf serum (Sigma). hCK cells were maintained in the presence of 2 μg/ml puromycin and 10 μg/ml blasticidin in MEM containing 5% newborn calf serum11. Adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial (A549) cells were maintained in Ham’s F12K (Wako) containing 10% fetal calf serum. All cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and tested for mycoplasma contamination using PCR and were confirmed to be mycoplasma free.

Viruses

Human influenza viruses were propagated in hCK or MDCK cells in MEM containing 1 μg L-1-tosylamide-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-trypsin (Worthington Biochemical Corpor) per ml.

Haemagglutination assay

Viruses (50 µl) were serially diluted with 50 µl of PBS in a microtiter plate. An equal volume (i.e., 50 µl) of a 0.55% (vol/vol) suspension of TRBCs was added to each well. The plates were kept at 4 °C and haemagglutination was assessed after a 1 h incubation.

Thermostability of viral infectivity

Viruses (107 plaque forming units in MEM containing 0.3% BSA) were incubated for the times indicated at 33 °C or 39 °C with 5% CO2. Subsequently, infectivity was assessed by use of plaque assays in hCK cells. Viruses (128 HA units in PBS) were incubated for 1 h at 30 °C, 50 °C, 60 °C, or 70 °C. Subsequently, haemagglutination (HA) activity was determined by use of HA assays using 0.55% TRBCs.

Western blot analysis

Samples were boiled at 100 °C for 10 min with or without the addition of 2-mercaptoethanol. The SDS-PAGE was performed using a precast polyacrylamide gel (e-PAGEL E-T520L, ATTO). The proteins were electrically transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, MilliporeSigma). The membranes were blocked in skim milk and stained with the following primary antibody: rabbit antisera against B/Yamagata/1/73 strain25 or anti-beta actin (mouse IgG1, Cat# 010-27841, FUJIFILM Wako). Blots were rinsed with PBS-T four times and stained with secondary antibody (HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies, Cat# 115-035-003, Jackson; or HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, Cat# 111-035-003, Jackson), and imaged using a ImmunoStar Zeta (Wako) or ImmunoStar LD (Wako). The chemiluminescent blots were imaged with the ChemiDoc XRS+ imager (Bio-Rad).

Haemadsorption assay

A549 cells were infected with viruses at an MOI of 5 at different temperatures (33 °C, 37 °C, or 39 °C). 24 h later, the culture supernatants were removed and then incubated with 500 μl of 1% TRBCs at 4 °C for 1 h. After being washed five times with ice-cold PBS, the cells were observed under a light microscope. For quantification, the A549 cells and erythrocytes were lysed with distilled water. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the absorbance at 560 nm of the released haemoglobin was measured.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed in GraphPad Prism software (version 9.4.0 and 10.3.1). Statistical analysis included ANOVA with multiple corrections post-tests. Differences among groups were considered significant for P-values < 0.05.

Responses