Understanding and addressing antenatal depression management in the high risk obstetrics care setting

Introduction

Maternal and women’s health has continued to worsen in the US in recent years. The rate of pregnant women dying has increased sharply over the last 40 years, and racial disparities in maternal outcomes continue to contribute to those increasing rates (https://doi.org/10.26099/ecxf-a664). Depression affects up to 20% of pregnant women, is associated with obstetric complications, and is one of the leading factors contributing to maternal mortality1. Those who experience antenatal depression are also likely to experience postpartum depression, particularly if depressive symptoms are unaddressed during pregnancy2. Furthermore, high-risk pregnancies are associated with a higher risk of antenatal depression compared to low-risk pregnancies3. Untreated or undertreated perinatal mental health conditions have negative consequences for the mother and baby, including cesarean delivery, preterm birth, low birth weight babies, and maternal mortality4. Unfortunately, despite the availability of effective treatments, most pregnant patients cannot access the care they need due to a range of factors, including stigma, workforce shortages, and challenges with longitudinal care5.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) strongly recommends depression screening for all perinatal women at the initial prenatal visit, later in pregnancy, and at the postpartum visit. Recommended first-line pharmacotherapy for perinatal depression are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), with follow up within 1 month using validated screening tools, such as the Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9) or Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)6,7. These tools should be used to monitor response to treatment and remission, and dosages should be titrated accordingly.

Despite these guidelines, depression screening and prescribing practices still vary among obstetrician-gynecologists (OBGYNs) and among practices. Many report routinely screening patients at least once during or after pregnancy, and comfort in prescribing antidepressants when depressive symptoms are present varies8. For many young individuals, pregnancy is often the first entry into the health care system and qualifies one for public health insurance coverage (e.g. Medicaid) if not previously insured. In addition, although depression is more common in marginalized populations, screening and treatment rates are lower for marginalized populations and those experiencing racism and socioeconomic inequities9.

While screening is an important tool to identify patients at risk for depression, it is important that such screenings occur within systems that allow for progression down proper treatment and follow-up plans after detection of depressive symptoms, as well as provide timely and affordable access to mental health resources such as psychotherapy, social work, and community support resources. However, many existing practices lack the necessary resources to effectively provide these services, which has prompted various initiatives to implement comprehensive behavioral health care delivery in antepartum obstetrics care9,10,11. Furthermore, limited integrated models exist in obstetrics care to address perinatal mental health12,13,14, and few focus specifically on medically high-risk patients experiencing depression.

The overall objective of this study is to identify qualitative aspects and timing of perinatal depression screening and intervention at a high-risk obstetric clinic to address existing gaps in care. The primary outcome is to evaluate characteristics of patients who screened positive on PHQ-9 during their pregnancy. The secondary objectives are to evaluate depression screenings and interventions, such as referrals and medication starts, provided for high-risk pregnant patients to demonstrate an existing need for systems level changes. The study is expected to provide insights into the effectiveness of current screening and intervention practices in obstetric care settings.

Results

Patient cohort and demographics

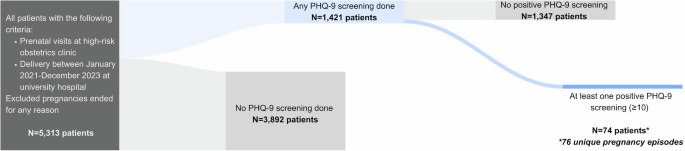

Of 5313 patients who met criteria for delivery and prenatal visits, 1421 patients (26.7%) had any PHQ-9 screen during pregnancy; there were 74 patients (5.2%) who had at least one positive screening (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10) in a pregnancy during the timeframe for a total of 76 unique pregnancy episodes with positive screens (2 patients had 2 separate pregnancies meeting criteria in this timeframe). Almost half of the pregnant women were Black or African American (48.6%, n = 36) and about a third were White (36.5%, n = 27). About a quarter of the patient cohort was Hispanic or Latino (25.7%, n = 19). Most patients indicated that their preferred language was English (81.1%, n = 60). Spanish was the preferred language for 13 patients (17.6%).

For all following results, we count unique pregnancy episodes (n = 76).

Cohort medical history

About a third of patients were nulliparous (31.6%, n = 24). The most common medical conditions included anemia (30.3%, n = 23), sexually transmitted disease (25.0%, n = 19), asthma (23.7%, n = 18), and gestational diabetes (19.7%, n = 15). See Supplementary Table 1 for a comprehensive description of medical comorbidities.

Cohort psychiatric history

A majority of patients had a documented pre-existing mental health diagnosis before the index pregnancy (81.6%, n = 62), and many had a history of mood disorder during a prior pregnancy (27.6%, n = 21). The most common diagnoses were depression (67.1%, n = 51), anxiety (65.8%, n = 50), and post-traumatic stress disorder (21.1%, n = 16). Over a quarter of patients had a documented history of interpersonal violence (28.9%, n = 22). Additionally, 26.7% (n = 20) patients faced documented financial stressors and 19.7% (n = 15) had documented substance use, including alcohol, tobacco, THC, cocaine, and opioids, during pregnancy. Regarding psychiatric treatment prior to pregnancy, 36.8% (n = 28) of patients had taken a psychiatric medication within 1 year and 28.9% (n = 22) had participated in psychotherapy. See Supplementary Table 2 for comprehensive psychiatric history and characteristics.

General prenatal care through delivery

The average age at delivery was 30.47 (SD = 6.48). 72.4% (n = 55) of patients had Medicaid coverage and 30.3% (n = 23) had private insurance at the time of delivery. 60.5% (n = 46) of patients had a vaginal delivery and 39.5% (n = 30) had a cesarean section. About two-fifths of patients had a premature delivery, defined as delivery before 37 weeks gestation. More than half of the patients had delivery complications. 22.4% (n = 17) of patients were transferred to high-risk obstetrics from general prenatal care during their pregnancy. 7.9% (n = 6) were noted to have limited prenatal care, defined as <5 total prenatal visits or entry to prenatal care after 20 weeks’ gestation.

Prenatal depression screening

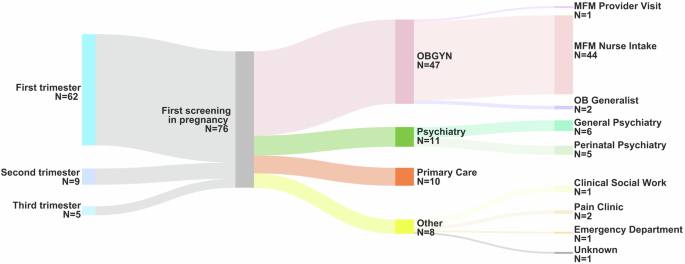

Patients received an average of 1.82 (SD = 1.36) PHQ-9 depression screenings throughout their pregnancy. Most initial screenings (80.3%, n = 61) occurred during the first trimester, with fewer initial screenings happening in the second (10.5%, n = 8) and third trimester (6.6%, n = 5). The high-risk obstetrics clinic nurse intake visit was the most common setting for the first-trimester screening (57.9%, n = 44), followed by primary care provider visits (13.2%, n = 10) and general or perinatal psychiatry visits (14.5%, n = 11). Other initial screening settings included clinical social work encounters, general obstetrics clinics, pain specialist clinics, a high-risk obstetrics provider visit, and an emergency department visit. A majority of patients had a positive initial depression screening. After initial screening, the mean number of follow-up screenings was 0.82 (SD = 1.36). Only 43% of patients received a second PHQ-9 screening during their pregnancy. See Fig. 1 and Table 1 for more details on initial screenings.

This figure, created using Sankey Art and Canva Pro, shows the timing (left) and location (right) of initial depression screenings for patients during pregnancy. On the left, the timing of screenings is illustrated across different trimesters). On the right, the locations of the screenings are depicted. OBGYN Obstetrician gynecologist. MFM Maternal fetal medicine. OB Obstetrician.

Medication interventions during pregnancy

Less than half of the cohort (34.2%, n = 26) were prescribed an SSRI medication before pregnancy. Of these, 18 (69.2%) patients continued taking an SSRI throughout pregnancy. However, follow-up with the prescriber was variable. 8 patients (44.4%) had at least one follow-up appointment with their original prescriber during pregnancy, while 10 patients (55.6%) continued taking the medication without any documented follow-up by their provider. 8 patients discontinued their SSRI use: 3 before pregnancy, 2 at the start of pregnancy, 2 during pregnancy, and 1 for unknown reasons.

New SSRI prescriptions were initiated for 18 patients (23.7%) during pregnancy. The high-risk obstetrics clinic prescribed 11 (61.1%), while a psychiatric provider prescribed 7 (38.9%). For prescriptions started by a high-risk obstetrics provider, 6 (54.5%) were not preceded by a validated depression screening, and 10 (90.9%) lacked documented follow-up with a validated screening tool. However, all patients (100%, n = 11) had documented general follow-up visits with notes acknowledging continued SSRI use and a subjective mood assessment. 14 patients had their SSRI adjusted by OB during pregnancy. 12 (85.7%) medications were adjusted without an associated PHQ-9. See Table 2 for comprehensive details about medication management in pregnancy.

General interventions in pregnancy

Among the 76 unique pregnancies with a positive PHQ-9 screen, 65.8% (n = 50) of patients received at least one intervention as part of their follow-up care. Of the interventions provided, 50.0% (n = 25) of patients received a clinical social work or psychotherapy referral, 38.0% (n = 19) of patients received other referral, 16.0% of patients received a psychiatry referral, and 8.0% of patients received a referral for community resources. Of the psychiatry and clinical social work or psychotherapy referrals, 75% (n = 6/8) and 72.0% (n = 18/25) of each type of referral were completed, respectively. Some patients did not receive any intervention (28.0%, n = 14) or declined the intervention that was offered (4.0%, n = 2), but their provider documented a plan to continue to monitor. About a third of patients did not receive interventions and did not have a documented plan to support their mental health needs or address social drivers of health (34.2%, n = 26). Postpartum mood check referrals were placed for 44.7% (n = 34) of patients; of those, 58.8% (n = 20) had a documented postpartum mood check completed. See Table 3 for more details about general interventions provided during pregnancy.

Postpartum care

Patient data was also collected regarding postpartum care. Out of 76 pregnancies, 15.8% (n = 12) of patients did not attend any postpartum visit. Of the 64 patients who did attend a postpartum visit, 52% (n = 33) had a positive EPDS score.

Discussion

This study sought to evaluate the characteristics of high-risk patients who screened positive for depression during pregnancy and to evaluate depression screenings and interventions, such as referrals and medication starts, provided for high-risk pregnant patients. Our study specifically focuses on the 74 patients who screened positive for depression, driven by our concern about the characteristics of and subsequent care provided to these individuals. Importantly, we were unable to determine patients’ response to treatment or if remission from depressive symptoms was eventually achieved, given the lack of systematic monitoring with a validated depression screening tool. By concentrating on the care pathways for those who screen positive, we highlight the importance of comprehensive support systems in improving patient outcomes.

A significant amount of our patient cohort had a history of mental health diagnoses, notably depression and anxiety; many had a history of interpersonal violence, and a considerable portion were Medicaid beneficiaries. Consistent with prior studies, personal history of depression, anxiety, trauma, and domestic violence, as well as being on Medicaid coverage, has previously been studied and associated with a higher likelihood of developing depressive symptoms during pregnancy15. The characteristics highlighted in our cohort reflect important factors that, according to prior studies, place this population at high risk and indicate a need for additional support when identified. The high proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries also underscores the role of social determinants of health in perinatal depression; addressing factors such as housing and food security, access to affordable childcare, and additional social support systems may help prevent and manage depression during pregnancy. In 2022, North Carolina Medicaid extended postpartum coverage from 60 days postpartum to up to 12 months postpartum, demonstrating a push for increasing access to both perinatal mental and physical health care16. Increased efforts in building sustainable and accessible care across sectors for Medicaid populations, especially given extended postpartum coverage, would be instrumental in improving patient and population level health. For individuals with increased risk factors, tailored interventions may prove effective, such as earlier or more frequent screenings and earlier referrals to mental health specialists.

Our study also revealed a concerning low rate of antenatal depression screening for patients seeking high-risk obstetrics care. While our research is not primarily focused on screening rates and barriers, this finding reveals a significant gap in screening practice, especially given ACOG recommendations for universal depression screening. Our findings are on par with a recent study on prevalence of prenatal screening in a large health system finding that screening ranged widely by clinic, from 34% – 100% across 35 clinics within a large health system9. There are many factors that lead to these differences across clinics and providers, though the lack of mandated screening in North Carolina also likely contributes in part to this shortfall for our context (https://policycentermmh.org). Currently, only eight states mandate at least one maternal mental health screening during pregnancy or postpartum. However, none of these mandates require screening specifically during the antepartum period, and North Carolina, where our study took place, does not mandate any screening for antepartum or postpartum depression at the time of this study. Universal depression screening during pregnancy has also been shown to increase detection, subsequent intervention, and improve depressive symptoms when implemented in a large health system, and should be considered as one part of the solution11. Factors contributing to higher screening rates also include clinics where depression management was an identified clinic priority, established prompts within the electronic health record, inclusion of screening in clinic workflows, and having a nurse champion invested in depression screening17,18. The gaps revealed in our study may be addressed by implementing elements of these evidence based practices to improve depression detection and continued management during pregnancy, particularly for high-risk patients. Nevertheless, implementing universal depression screening without ensuring proper follow-up and care may not yield the anticipated positive outcomes.

In our cohort, most initial screenings occurred during the first trimester, though limited follow-up throughout pregnancy suggests a gap in ongoing monitoring and interventions provided. The high proportion of screenings conducted at high-risk obstetrics settings highlights the importance of integrating effective care management practices into settings where screenings occur; screenings in other clinical settings also point to the need for more effective communication between all healthcare providers involved in pregnancy care, especially with a substantial number of patients in this cohort being transferred to high-risk obstetrics care from another prenatal setting. High rates of mid-pregnancy transfer of care due to emerging obstetrics complication, compounded with fragmentation of care due lack of integrated systems, may contribute to gaps in delivering whole-person care. The impact of those initial screenings becomes null if there is a lack in follow-up by providers taking over care.

Our study showed that while these patients all received at least one depression screening during pregnancy, many of them did not receive comprehensive longitudinal follow-up throughout their pregnancy to address their symptoms. A majority screened positive on their initial screen, but only about 65% received any direct intervention, including medication or referrals to psychiatry, social work, or community resources. Of those that did receive referrals, approximately one-third of those referrals were not completed. These findings are consistent with previous study findings, which have shown a perceived lack of referral networks, insufficient resources, and limited time of obstetricians to provide thorough depression follow-up and care coordination5,10,17,19. Given the other complex medical co-morbidities high-risk obstetrics patients have, it is imperative to provide comprehensive clinical support to address gaps from both the patient and provider perspectives.

Our study highlights that many high-risk obstetric providers serve as primary prescribers for SSRIs during pregnancy, and while the willingness to initiate treatment is evident, the absence of standardized protocols presents an opportunity for improvement in care delivery. Notably, over half of new SSRI prescriptions initiated by high-risk obstetric providers lacked a documented, validated depression screening at the time of starting medication. While all patients received some form of general follow-up, only one had documented follow-up with a validated screening tool within the recommended timeframe after initiating medication. Validated screening tools, such as the PHQ-9, are crucial to effectively track depressive symptoms, treatment response, and potential side effects20. However, there is notable variability in how these tools are utilized in practice, including patients being sent forms prior to the visit, during check-in or intake, or at the time of the visit itself. The lack of a standardized workflow makes it challenging to assess the quality and thoroughness of these follow-ups and leaves room for discrepancies in care. In such instances, clinicians rely on their clinical judgment and direct patient reports, which, while appropriate, may introduce potential gaps in the systematic tracking of mood changes over time, especially with regard to medication titration.

Regarding postpartum care, a significant percentage of our cohort were referred to receive a postpartum mood check, which involves a brief telephone call by a nurse or provider to assess mood symptoms and provide interventions as necessary within 2 weeks of hospital discharge. In this health system, mood check referrals can be placed by any provider during pregnancy or hospitalization surrounding delivery, indicating a clear recognition of the importance of monitoring mental health beyond the antepartum period. However, the completion rate was just over 50%, indicating that a variety of barriers may exist for patients needing postpartum mental healthcare. Factors such as untreated or undertreated depression, and stress related to lack of childcare options, transportation issues, or inadequate medical coverage could contribute to these challenges and should be acknowledged when considering system-wide solutions.

Our study has some limitations. First, given that this is a retrospective observational study, we are limited by data available through the electronic health record and cannot ensure that potential confounders are controlled. Specifically, our methodology may not capture any depression screenings that were completed in a clinic but not documented in the record. Second, our sample size and focus on a single health system limits the generalizability of this study due to selection bias. Third, while we used the PHQ-9 screen to identify our cohort, it should be acknowledged that the EPDS is also a validated screening tools appropriate for use during pregnancy. In our cohort, the PHQ-9 was the standard practice for antenatal screening at the high-risk obstetrics practice where this study was conducted. During this study period, EPDS data were only collected for patients in postpartum visits. Given the absence of antenatal EPDS data integration in this clinic’s electronic health record system, we expect its use to be negligible in our cohort. Nevertheless, the lack of standardization and variability across providers means that our methodology may not capture patients who may have been screened for depression antenatally using the EPDS and may obscure a more comprehensive understanding of initial and follow-up screening practices. This raises concerns about potentially missed cases of antenatal depression given established prevalence rates. Future studies should aim to include both the PHQ-9 and EPDS to capture the full spectrum of depression screening methods. Finally, our described patient characteristics for this cohort are limited to the patients who received screening. Given noted variability in screening methods, this may reflect existing bias in who is and is not screened. If universal screening were to be implemented, noted patient characteristics of those experiencing depression during a high risk pregnancy may change.

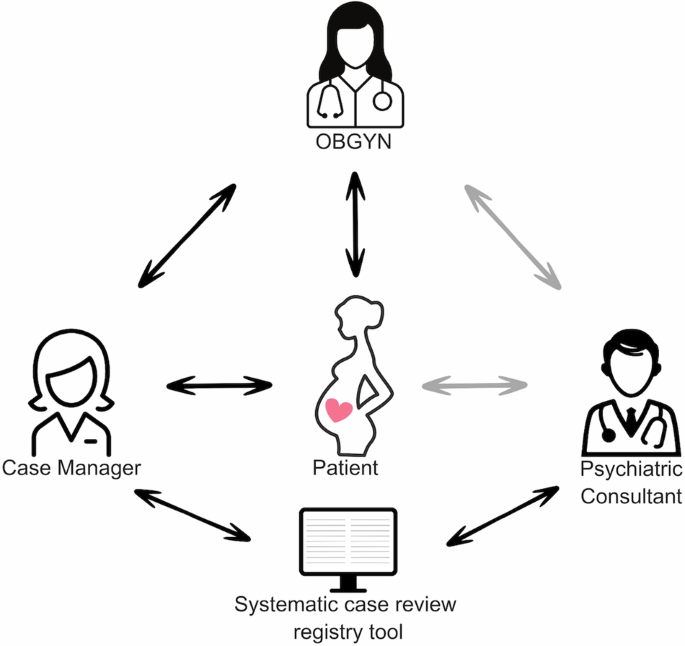

To address gaps in care, integrating behavioral health care delivery with obstetric care has been proposed as a feasible solution to increase access to effective follow-up and decrease the fragmentation of care for pregnant women12,13,21. In primary care, the collaborative care model (CoCM) has been established as the gold standard of care for treating depression (https://www.ncahec.net/practice-support/collaborative-care-2/)22,23. This model includes universal depression screening with the PHQ-9, a care manager responsible for coordinating care between the primary provider, psychiatric consultant, and patient, a registry of positive screens that allows the case manager to follow-up with patients and track symptoms and response to treatment (https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/). The care manager regularly reviews the registry with the psychiatric consultant, discusses recommendations for interventions or resources to provide, and then communicates directly with the primary provider to implement these recommendations. Given its effectiveness in primary care settings, it has also begun to be used in general obstetrics practices and have shown great effectiveness in addressing depression in pregnant patients12,24,25. The proposed CoCM framework for perinatal mental health would parallel existing workflow of CoCM in primary care, with the obstetrics provider as the primary provider (see Fig. 2). Prioritizing a high-risk population for early postpartum mental health screening and support group participation within the CoCM network may be beneficial.

This figure, created using Canva Pro, illustrates the flow of care in a perinatal collaborative care model. At the center, the patient is depicted as the focal point, receiving care from both the obstetrician-gynecologist (OBGYN) and the case manager, who play key roles in managing the patient’s care throughout the perinatal period. The psychiatric consultant is available to review patient cases, with access to a registry tool that allows for collaboration and case review alongside the OBGYN and case manager.

The high prevalence of risk factors for depression among our patient cohort also underscores the importance of universal screening within the CoCM framework. Validated tools like the PHQ-9 or EPDS could be used for more consistent screenings, incorporated into existing high-risk obstetric clinic visits at designated points in the first trimester, third trimester, and postpartum. For patients who screen positive, CoCM’s structured approach supports coordination of regular follow-ups to monitor symptoms, assess treatment responses, and make necessary adjustments to care plans, which would address the high percentage of patients in our cohort who did not receive adequate follow-up. Once a patient screens positive, care managers would provide brief therapeutic interventions and medication management with the support of the psychiatric consultant. The care manager within CoCM would be crucial in monitoring these patients, actively building an internal registry, monitoring symptoms using validated screening tools at regular intervals (every 2 weeks when possible), noting concerning symptoms, helping to adjust medication dosage with the psychiatric consultant and OB, and ensuring timely follow-up appointments with mental health specialists as needed. Partnering with on-site or affiliated perinatal care managers and psychiatric consultants within CoCM is crucial, and their expertise in managing depression during complex pregnancies is invaluable, particularly when medication interactions or co-morbidities require specialized care. Additionally, collaborating with social workers and patient navigators is essential to address the specific challenges faced by this population. By providing tailored support systems and addressing these specific needs, the CoCM behavioral health care manager can ensure comprehensive care for high-risk patients throughout the entire perinatal period and across health systems.

Overall, this study underscores significant gaps in the management of perinatal depression among high-risk pregnant patients, particularly in terms of inadequate follow-up after initial screening and lack of systematic use of validated tools to track depressive symptoms. Although many patients screened positive for depression, the majority did not receive structured care, and interventions such as medication or mental health referrals were inconsistently provided. The lack of standardized workflows for screening and follow-up limits the ability to monitor treatment response and adjust care plans effectively. Furthermore, the low completion rate of postpartum mood checks highlights persistent barriers to accessing mental health care during the critical postpartum period. The variability in screening and follow-up practices, combined with fragmented care, presents an opportunity to improve the care provided to this vulnerable population. There are many national and state-level pushes towards investing in both integrated behavioral healthcare and maternal mental health16,21,26,27. An integrated approach could lead to earlier intervention, improved medication management, and comprehensive support throughout pregnancy and postpartum, ultimately contributing to better maternal and infant health outcomes. Future studies should compare these approaches to determine the best strategies for improving care in high-risk obstetric populations. Ultimately, addressing the mental health needs of this population and existing system-level gaps requires a multi-faceted approach, including reliable screening practices, improved care coordination, and greater access to mental health resources.

Methods

Participants

This was a retrospective cohort study of women who delivered a baby at an academic medical center hospital located in the Southeast United States between January 2021 and December 2023. Inclusion criteria included having at least one prenatal visit at the same academic center’s high-risk obstetrics practice and a score of 10 or greater on any PHQ-9 screening documented in a MaestroCare flowsheet within 1 month of any prenatal visit during pregnancy. The start of a pregnancy episode was defined by the date of the first documented note by any provider acknowledging pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included neonatal or fetal demise or deceased birthing patients.

Materials and procedure

Data were extracted from the electronic medical record using SlicerDicer based on inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 3). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Duke University School of Medicine28,29,30. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources. All data involving human participants in this study were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. A waiver of informed consent was granted by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of the study and the minimal risk involved, as it relied on de-identified data without direct interaction with participants.

This Sankey diagram, created using Sankey Art and Canva Pro, illustrates the methodology used to identify the final cohort of patients in this study. Starting with 5,313 patients who met the initial inclusion criteria, the diagram shows the subsequent steps in the screening process. The first flow represents patients who underwent depression screening, followed by those who had a positive screening result. The final cohort consists of 74 patients, with a total of 76 unique pregnancy episodes. PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Data analysis

Frequencies and percentages were calculated to characterize patient demographics and clinical history, prenatal care and delivery episode care, postpartum characteristics, prenatal depression screening, and behavioral health care management plans during pregnancy episodes. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27).

Responses