Genomic insights into gestational weight gain uncover tissue-specific mechanisms and pathways

Introduction

Deviation from recommendations for gestational weight gain (GWG) has profound multigenerational consequences on pregnant persons and their children1,2,3,4. Roughly 70% of pregnant individuals in the United States (U.S.) do not fall within the recommended weight range5,6. Despite the significant public health burden of GWG, interventions, which largely focus on diet and physical activity during pregnancy, have had limited success in improving perinatal outcomes and are often difficult to adhere to outside of clinical trials7.

GWG is a complex phenotype, likely determined by a combination of genetic, metabolic, and environmental factors6,8. Weight gain, and its underlying biology, varies over the course of pregnancy. The modest weight gain in the first trimester is largely due to placental development and expansion of maternal blood volume, while larger weight gain in later trimesters is due to increasing fetal growth and development9,10. Twin studies have shown this weight gain is due, in part, to genetic variation with heritability ranging between 36% and 51% in studies conducted in nulliparous individuals11. Previous research has further investigated the genetic basis of GWG. A genome-wide association study (GWAS) investigated the genetic contribution to early, late, and total GWG using variants in both fetal and maternal genomes12. A single variant in offspring genomes reached genome-wide significance for total GWG but did not replicate. However, several variants that have been previously associated with related phenotypes, including increased body mass index (BMI), fasting glucose, and type 2 diabetes, were nominally significant. However, the biologic mechanisms and tissue-specificity underlying the role of these variants in GWG remains unknown.

Our objective was to evaluate the association between tissue-specific genetically predicted gene expression (GPGE) and GWG and interrogate biological pathways represented by the identified genes. We investigated associations in five tissues relevant to GWG using genotypes from pregnant persons. As the placenta is a key component of weight gain during pregnancy, we also examined the connection between GWG and gene expression in the placenta using fetal genotypes. Finally, since tissues that contribute to GWG are known to vary over the course of pregnancy, we evaluated these associations based on early, late, and total GWG.

Results

Genetically predicted gene expression

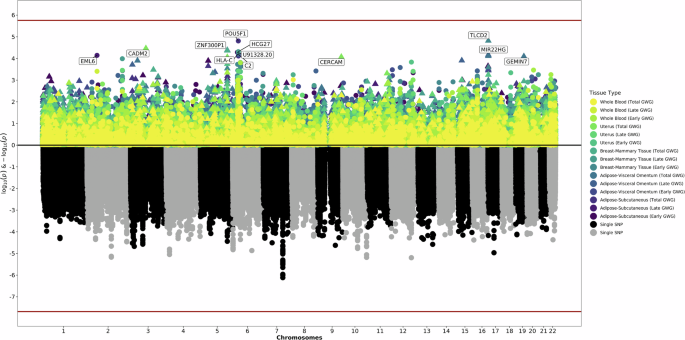

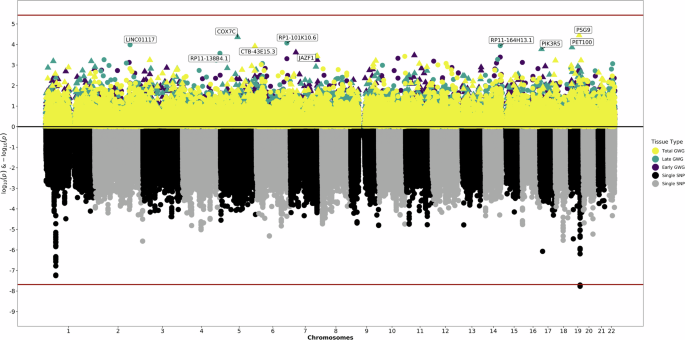

We tested the association of genetically predicted maternal or fetal gene expression with early, late, or total GWG in five maternal tissues and fetal placenta. We evaluated a total of 28,767 maternal gene-tissue pairs across subcutaneous and visceral adipose, breast, uterus, and whole blood; and a total of 14,145 fetal gene-tissue pairs in placenta (Supplementary Data 1–2). There were no associations between GPGE in any tissue and early, late, or total GWG following multiple testing correction. There were, however, a number of nominally significant (p < 0.05) findings in maternal tissues and fetal placenta (Table 1, Figs. 1–2).

The bottom of the graphic is a Manhattan plot which displays significant SNPs from the previous GWAS. The top of the graphic is the results from S-PrediXcan, with symbols now corresponding to genetically predicted expression levels of genes and the significance of their association with gestational weight gain. The x-axis are chromosomes. The y-axis is log and negative log p-values for the GWAS and S-PrediXcan analyses. Colors correspond to specific tissues and definitions of gestational weight gain.

The bottom of the graphic is a Manhattan plot which displays significant SNPs from the previous GWAS. The top of the graphic is the results from S-PrediXcan, with symbols now corresponding to genetically predicted expression levels of genes and the significance of their association with gestational weight gain. The x-axis are chromosomes. The y-axis is log and negative log p-values for the GWAS and S-PrediXcan analyses. Colors correspond to specific definitions of gestational weight gain.

GPGE in maternal tissues revealed important developmental and immune factors in early GWG, while results for late GWG reflected changes affecting cellular structures and interactions. POU5F1 (β = −0.15, p = 1.55 × 10−5), which plays a key role in embryonic development and stem cell pluripotency, had the most significant association with early GWG in maternal whole blood but was also nominally associated with late and total GWG in maternal whole blood. These results suggest that increased expression of POU5F1 may be associated with decreased early GWG.

Genetically-predicted expression of multiple genes (HCG27 [β = −0.15, p = 4.86 × 10-5], HLA-C [β = 0.17, p = 5.87 × 10-5], C2 [β = 0.24, p = 7.68 × 10-5]) involved in the immune system was also most strongly tied to early GWG in maternal tissues. Among early, late, and total GWG, HLA-C was nominally significant for all maternal tissues except subcutaneous adipose, while C2 was nominally significant for only whole blood. HCG27 was more consistently tied to predicted expression changes in maternal adipose tissue, with nominal associations detected for early, late, and total GWG. The leading maternal associations with late GWG were genetically-predicted expression of genes involved in cell aggregation, adhesion, and proliferation, with additional roles in splicing and membrane rigidity (CADM2 [β = _0.29, p = 3.39 × 10−5], ZNF300P1 [β = 0.08, p = 4.11 × 10−5], TLCD2 [β = −0.26, p = 7.73 × 10−5], GEMIN7 [β = 0.93, p = 7.98 × 10−5]).

In fetal placenta, genetically-predicted expression of genes involved in transcription and cell proliferation (JAZF1 [β = 0.08, p = 2.44 × 10−4], ALX4 [β = −0.16, p = 3.35 × 10−4], TLC1A [β = −0.13, p = 4.10 × 10−4]) were linked to early GWG, while expression of genes with mitochondria functions or previously implicated in cancers (COX7C [β = 0.32, p = 4.34 × 10−5], PET100 [β = 0.14, p = 1.38 × 10−4], LINC01117 [β = 0.19, p = 1.03 × 10−4], RP11-164H13.1 [β = 0.18, p = 1.14 × 10−4]) were tied to late GWG. Fetal placenta expression of PSG9 (β = −0.11, p = 3.57 × 10-5) had the most significant association with total GWG.

Functional annotation

We performed gene set enrichment analyses incorporating nominally significant genes from our maternal and fetal analyses using Functional Mapping and Annotation of Genome-Wide Association Studies’ (FUMA’s) GENE2FUNC tool. In maternal tissues, intracellular, vesicle-mediated, intracellular protein transport, Golgi vesicle transport, and establish of protein localization processes were associated with early GWG (Supplementary Fig. 1). Purine nucleotide binding was an enriched function for both early and late GWG. Sulfur compound metabolic processes were associated with total GWG (Supplementary Fig. 2). Nominally significant genes from the maternal early and total GWG analysis have also been previously associated with several related phenotypes, including waist and hip circumferences adjusted for BMI (Supplementary Fig. 3). There was no enrichment of processes or functions in nominally significant genes from fetal analyses.

Discussion

We tested the association between GWG and tissue specific GPGE using five relevant maternal tissues and the fetal placenta. Many nominally significant associations demonstrated strong biologic plausibility. In maternal analyses, genes involved in immune system were among the top associations for early GWG; while top associations for late GWG included genes with function in cell aggregation, adhesion, and proliferation. There was also significant enrichment of several biologic pathways, such as metabolic processes, secretion, and intracellular transport, among nominally significant genes from the maternal analyses. The enriched biological pathways varied by pregnancy stage (e.g., early vs late GWG). In fetal analyses, placental expression of a gene encoding a pregnancy-specific protein was the leading association with total GWG. In addition to the top genes’ involvement in relevant biological processes, several of these genes have been previously tied to relevant phenotypes, including BMI and waist to hip ratio. After correcting for multiple testing, however, we did not find statistically significant associations between maternal and fetal tissue-specific gene expression and early, late, or total of GWG.

Previous research has found a moderate genetic contribution to weight gain. The only GWAS for GWG to date, from which summary statistics for our study were obtained, concluded that roughly 20% of the variability in GWG can be explained by common maternal variants, with variants from the fetal genome contributing a much smaller amount12. Other genetic studies, investigating only candidate variants or genes have also been performed. Previous research has found associations with variants tied to obesity and diabetes, including SNPs in KCNQ1, PPARG, and GNB312,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. A recent study found risk variants in TMEM18 and GNB3 are more frequent in females with increased GWG, a variant in GNPDA2 was more frequent in those with adequate GWG, and a variant in LEPR was more common in individuals with decreased GWG17. Unfortunately, there are currently no gene expression prediction models for KCNQ1 and PPARG in the maternal tissues. GNB3, TMEM18, GNPDA2, and LEPR was not significant in any tissue in the maternal analyses. KCNQ1, PPARG, GNB3, GNPDA2, and LEPR were also not significant in any fetal analyses. TMEM18 was nominally significant in only the early GWG fetal analysis (β = 0.04, p = 0.03).

The Warrington et al. study found a single variant in offspring genome that was significantly associated with total GWG: PSG512. Interestingly, the top nominally significant association in the fetal placenta analysis for total GWG was another pregnancy-specific beta-1 glycoprotein: PSG9. PSGs are produced by placental trophoblasts and secreted into the maternal bloodstream in increasing amounts throughout pregnancy20. The function of these proteins is not fully known, but they have several hypothesized roles, including modulation of the maternal immune system to avoid rejection of the fetus. Previous studies reveal an association between these proteins and preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction21,22. Our findings are consistent with previous work on PSGs and fetal growth restriction indicating that increased expression of PSG9 is associated with decreased total GWG.

Overexpression of JAZF1, the top nominally significant association with early GWG in the placenta, has been shown to reduce body weight gain and regulate lipid metabolism in mice models23. In contrast, our results demonstrate increased placental expression was associated with increased GWG in early pregnancy. JAZF1 has been previously implicated in GWAS for type 2 diabetes, body fat distribution, and BMI24,25,26,27. The top suggestive associations in early (POU5F1-whole blood), late (CADM1-breast), and total (TLCD2-subcutaneous adipose) GWG using maternal genotypes have also been tied to related traits, including BMI, BMI-adjusted hip circumference, type 2 diabetes, and waist to hip ratio26,28,29,30,31,32. ALX4, another gene that had a nominal significant association with early GWG in the fetal placenta, has also been tied to a related phenotype: early pregnancy dyslipidemia33. Previous research, which directly measured RNA levels, found decreased expression of ALX4 in the placenta was associated with high triglyceride levels. Our results showed an increasing ALX4 expression in the fetal placenta was associated with decreasing GWG in early pregnancy. Given the connection between triglycerides and weight (gain), the previous research lends further support to our findings and highlights a potentially interesting mechanism occurring in the placenta.

We observed additional associations that had strong biological plausibility in our analyses stratified by time of the GWG measurement. For example, there were many maternal immune system genes (HCG27, HLA-C, C2, etc.) nominally associated with early GWG. There is a strong biological basis for this association, as the maternal immune system must adapt early in pregnancy to ensure the fetus is not rejected. In the GWAS Catalog, previous associations for these genes notably include obesity traits like waist to hip ratio, in addition to other immune and blood traits and autoimmune disorders such as lupus and psoriasis. POU5F1, which plays a key role in embryonic development and stem cell pluripotency, had the most significant association with early GWG in maternal analyses. In contrast, expression of genes involved in cell aggregation, adhesion, and proliferation, as well as splicing and membrane rigidity (CADM2, ZNF300P1, TLCD2, GEMIN7) were the leading associations with late GWG in maternal analyses. In the fetal placenta, genetically predicted expression of genes involved in transcription and cell proliferation (JAZF1, ALX4, TLC1A) were linked to early GWG. Enriched biologic pathways and functions also differed based on period of GWG, though purine nucleotide binding was enriched in both early and late GWG of maternal analyses and fetal analyses did not display any enrichment in processes or functions.

There are several considerations related to the data utilized in this study. First, we utilized publicly available data from a GWAS of over 18,000 females and 21,000 offspring12. The previous study had numerous strengths, including its unique inclusion of genotypes from both birthing persons and their offspring and a large sample size, which provided adequate power for our analyses. However, all study participants were of European ancestry, potentially limiting generalizability of study results. Future research should include more diverse populations. As a secondary data analysis, we were also unable to modify the definitions of early, late, and total GWG. Both early and late GWG definitions used a cut-point of 18 to 20 gestational weeks. However, pregnancy is typically divided into three trimesters, which align with the physiological changes occurring in pregnant persons and their offspring. Our results could be impacted by the definition of GWG, which do not perfectly align with the trimester-specific changes. Investigating tissue-specific gene expression by trimester could result in more precision, biologically and clinically relevant results. Our investigation using maternal genotypes was limited to five tissues. Tissue selection was based on the known physiologic changes, as each of the selected tissues are known to expand or increase in size/volume and account for a substantial proportion of the amount of weight gained during pregnancy. Future research could expand to all maternal tissues and further identify unique associations at the tissue-level. Finally, pre-pregnancy BMI heavily influences GWG and recommendations for weight gain vary based on pre-pregnancy BMI. The association of tissue-specific gene expression with GWG could vary based on individual’s pre-pregnancy BMI. However, we are unable to further explore the impact of pre-pregnancy BMI thoroughly without individual level-data.

Our threshold for statistical significance accounts for the number of gene-tissue pairs tested. This threshold could be overly stringent as it does not take into account the correlation structures between coordinated expression both within tissues and for the same genes across tissues. Significance levels reported in this analysis could be overly conservative and not detect additional true effects that did not reach this threshold. GTEx and the corresponding tissue-specific prediction models for maternal analyses utilize samples of non-diseased tissues from both female and male donors with a variety of races and ages. Investigation using sex-specific models and/or reproductive females only could yield additional insight. Sample sizes varied based on tissue and ranged from 70 to over 400, which could also impact our power to detect associations. Additionally, GPGE models are only available for the fetal portion of the placenta. Creation of models using the maternal side of the placenta would be beneficial for direct comparison.

In conclusion, our approach furthers previous research by evaluating potential mechanisms by which genetic variation affects GWG, providing additional insight into the variation in GWG. Many of the genes whose expression was nominally significant possess functions that are likely relevant to weight gain in pregnancy. Associations varied by time of weight gain, broadly mirroring the events during pregnancy. For example, immune genes were top associations in early GWG, a time when maternal immune systems must quickly adapt to ensure the fetus is not rejected. Several of these genes have also been previously implicated in GWAS of related traits. These results further support that diverse biological pathways impact GWG, inferring that their influence is likely to vary based on individual and tissue, as well as over the course of pregnancy.

Methods

Genome-Wide association study data

GWAS summary statistics were obtained from a genome-wide meta-analysis on GWG. Data on GWG has been contributed by the Early Growth Genetics (EGG) Consortium and has been downloaded from www.egg-consortium.org12. The previous study used maternal and fetal genotypes to investigate three GWG definitions: early, late, and total. Early was calculated as the difference between pre-/early pregnancy weight and weight measured any time between 18 and 20 completed weeks divided by length of gestation in weeks at last measurement. Late GWG equaled the difference between 18- and 20-week measurement and last gestational weight measure at or after 28 weeks divided by the difference in gestational age in completed weeks between these two measurement times. Finally, total GWG was equivalent to the last gestational weight (at or after 28 weeks gestation) prior to delivery minus pre-/early-pregnancy weight divided by length of gestation in weeks at last measurement. Using maternal genotypes, the analyses contained up to 7704, 7681, or 10,555 individuals for early, late, and total GWG, respectively. For analyses using fetal genotypes, there were up to 8552, 8625, or 16,469 individuals in the meta-analyses of early, late, or total gestational weight. All singleton pregnancies that resulted in a term delivery where the child did not have a known congenital anomaly were included. All individuals in the 20 included pregnancy and birth cohorts were of European origin12.

Placental gene expression models

We have previously described our methods for creation of a placental gene expression model34,35. Briefly, placental gene expression and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) were evaluated and computed using published gene expression data from the Rhode Island Child Health Study36. Gene expression data on 150 samples were derived from placenta tissue excluding maternal decidua and processed using whole transcriptome RNAseq. As previously described, whole genome genotyping (Illumina MEGAex Array, Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) was used for generating eQTLs36. GPGE models were created using eQTL summary statistics. Within each gene, total eQTLs were filtered by a false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p-value less than 0.1. Linkage disequilibrium clumping was performed (0.1 r² and 250 kilobase window). To retain only genes with considerable genetic regulation in placenta, the variance explained by each eQTL single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was calculated and the sum of SNP variances was computed for each gene. Genes were then ordered by expression variance explained and those with variance of less than 0.01 or greater than two were excluded from the prediction models. Final models used 25,885 genetic variants associated with expression of 15,154 genes34,35. The placenta model was only used for analyses using fetal genotypes.

S-PrediXcan Analyses

Gene expression was estimated in tissues using the GWG GWAS summary statistics and S-PrediXcan. This method tests for association between the outcome and the tissue-specific genetically determined component of expression for genes using SNP-level association and eQTL summary statistics37. For analyses, S-PrediXcan was used to obtain gene expression estimates in five relevant maternal tissues (subcutaneous and visceral adipose, breast, uterus, and whole blood) using existing models from the Genotype Tissue Expression (GTEx v7) project (predictdb.org). We also evaluated associations between GPGE in the placenta and early, late, and total GWG using summary statistics from the GWAS using fetal genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 4). Bonferroni corrected p-values were used to determine significant gene associations (p < 1.74 × 10-6 for all maternal analyses, p-value < 3.58×10-6 for early and late GWG using fetal genotypes, and p < 3.54 × 10-6 for total GWG using fetal genotypes), though associations with p values less than 0.05 were considered nominally significant. All reported effect sizes equate to increasing predicted gene expression. We defined genes as previously implicated in GWAS studies if they were reported and mapped in the GWAS Catalog for each outcome definition. All results are based on publicly available data and do not constitute human subjects research.

Functional annotation

The GENE2FUNC module from the annotation tool FUMA was used to test for gene enrichment in cell types and pre-defined biological pathways for all significant and nominally associations38,39.

Responses