Differential association of selenium exposure with insulin resistance and β-cell function in middle age and older adults

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is recognized as an important public health problem with an enormous impact on society [1]. The etiopathogenic mechanisms of diabetes involve insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction, which commonly precede diabetes onset [2]. One of the main contributing factors for insulin resistance development is oxidative stress [3], which can impair insulin sensitivity, induce β-cell dysfunction and alter inflammatory response and insulin signaling pathways [4].

Selenium is an essential micronutrient, which is a component of selenocysteine-containing proteins (i.e., selenoproteins) with a key role in redox homeostasis, such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx) or selenoprotein P [5, 6]. Early experimental [7, 8] and epidemiological studies [9, 10] suggested a link between low selenium levels and higher risk of type 2 diabetes. Alternatively, a recent meta-analysis of observational and experimental studies has shown that high selenium was associated with incident and prevalent type 2 diabetes [11]. Thus, the accumulated evidence suggests that both selenium deficiency and excess are detrimental to glucose metabolism. However, associations between selenium and insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction have rarely been investigated in epidemiologic studies.

Recently, a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that blood selenium concentration was positively and linearly associated with insulin resistance [12]. However, longitudinal studies are needed. Also, it is unknown if this association differs by age, which is a relevant question because comorbidities at an older age are frequently associated with selenium-demanding biological processes [13] and because β-cell function decreases with age [14].

We evaluated the cross-sectional association of selenium exposure as measured in whole blood with insulin resistance and β-cell function, estimated using the homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and for β-cell function (HOMA-β, %) indexes, respectively [15]. We used data from diabetes-free middle-aged and older adults who participated in the Aragon Workers Health Study (AWHS) and the Senior Seniors-ENRICA-2 study (SEN-2), respectively, as well as participants from similar age subgroups in the 2011–2018 NHANES for replication of cross-sectional findings. We also tested the longitudinal dose–responses in a subsample of AWHS and SEN-2 participants with repeated HOMA measurements over time. The present work helps to characterize potential differential influences of selenium in the development of type 2 diabetes with aging.

Methods

Study populations

The AWHS (mean age 52 years) is a longitudinal cohort study based on the annual health exams of 5678 workers (93% men) of an Opel car assembly plant in Figueruelas (Zaragoza, Spain), which aims to characterize factors associated with metabolic abnormalities and subclinical atherosclerosis. The study design and data collection methods have been previously published [16]. Briefly, study participants were recruited during a standardized clinical exam between 2009 and 2010 (the participation rate was 95.6%). Among them, 2678 participants who were 40–55 years old in 2011 and attended yearly occupational health visits were randomly included in the atherosclerosis-imaging sub-cohort conducted in the 2011–2014 examination visit. A total of 1380 (out of 2678) participants who had available blood for selenium determinations collected in the 2011–2014 visit (baseline for the present analysis), were selected for this study. We excluded participants missing information on education, body mass index (BMI), or plasma insulin levels (N = 113), as well as participants with diabetes (N = 81, standard definition of fasting serum glucose >126 mg/dL, glycated hemoglobin > 6.5%, or glucose-lowering medication use). Finally, a total of 1186 AWHS participants were included in the cross-sectional analyses. A subset of 571 participants had repeated measurements of plasma insulin and glucose levels from yearly occupational health check-ups (median follow-up [interquartile range] = 12.0 [10.5, 13.3] months), which made up the study population for longitudinal analysis. The study was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board of Aragon (CEICA). All study participants provided written informed consent.

In the SEN-2 cohort (mean age 70 years) [17], the baseline examination was conducted between 2015 and 2017. In total, 3273 individuals were selected by sex- and district-stratified random sampling of all community-dwelling individuals aged ≥65 years holding a national healthcare card and living in the Madrid Region (Spain). Information regarding socio-demographics, lifestyle, self-rated health, and morbidity was collected using a computer-assisted telephone interview. Trained staff performed two home visits where a physical examination, a diet history, and biological samples were obtained. A total of 1124 (out of 3273) participants who had blood selenium, insulin, and glucose determinations at baseline were included in the analyses. From these, we excluded participants with diabetes (N = 209), leaving a total of 915 SEN-2 participants for the cross-sectional analyses. A subset of 603 participants who had a second measure for plasma insulin and glucose (25.4 [24.2, 27.1] months of follow-up) was selected for the longitudinal analysis. All participants provided written informed consent. The SEN-2 study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of La Paz University Hospital in Madrid.

In addition, we used the 2011–2018 NHANES data for replication of cross-sectional findings. Detailed information on the NHANES study population and methods is available in the Supplemental Material, Supplemental Methods.

All study participants provided written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations for Ethics in biomedical research.

Blood selenium levels

In AWHS, blood selenium levels were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) with dynamic reaction cell on an Agilent 7500ce ICP-MS at the Environmental Bioanalytical Chemistry Laboratory of the University of Huelva (Spain). In SEN–2, blood selenium was measured using ICP-MS (Agilent 8900 ICP-QQQ) at the Department of Legal Medicine, Toxicology, and Physical Anthropology, School of Medicine, University of Granada (Spain). Both laboratories used standardized protocols, which include the instrument tunning and performance parameters checks prior to analysis, the use of calibration standards with several dilutions, and the addition of internal standards to the samples and the calibration standards. Furthermore, a suitable certified reference material for whole blood was reanalyzed together with a blank and an intermediate calibration standard every 12 samples to ensure the accuracy of the analysis. National Institute of Standards and Technology NIST (USA) Trace Elements in Natural Water Standard Reference Material SRM 1640a was also used as certified reference material and analyzed at the beginning and at the end of each sequence. Additionally, one in every 12 samples was reanalyzed at the end of each session to check the precision of the analysis. The selenium determination methods used in this study have been successfully applied before [17, 18]. The limits of detection for blood selenium were 0.5, and 0.3 μg/L for AWHS and SEN-2, respectively. No samples had concentrations below the corresponding limits. The inter-assay coefficient of variation for selenium levels were 5.0 and 5.2% for AWHS and SEN-2, respectively.

HOMA-IR and HOMA-β outcomes

Fasting serum glucose (mg/dL) and insulin (µU/mL) were measured by spectrophotometry (Chemical Analyzer ILAB 650) with the manufacturer Instrumentation Laboratory kit and by double sandwich immunoassay in frozen samples in an Access 2 Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA) using the manufacturer ultrasensitive kit, respectively, in AWHS and by colourimetric enzymatic methods using Atellica Solution® (Siemens Healthineers) and immunoradiometric assay, respectively, in SEN-2.

To better evaluate potential differences in the association of selenium with HOMA outcomes by age, irrespective of the different laboratory techniques used in AWHS and SEN-2 for glucose and insulin determinations, we applied regression-based recalibration methods to serum glucose and insulin measurements in both discovery study populations using the NHANES 2011–2018 population as reference. Details of the NHANES study population and information, including the laboratory as well as recalibration methods, are provided in the Supplemental Material (Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Tables S1, S2, and S3).

The homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR, unitless) and β-cell function (HOMA-β, %), which determine insulin secretion, were estimated using the standard formulas glucose * insulin/405 for HOMA-IR, and 360 * insulin/(glucose – 63) for HOMA-β [15]. Higher values of HOMA-IR indicate greater insulin resistance, while lower values of HOMA-β indicate worse β-cell function.

For longitudinal analyses, we calculated the annual relative change in HOMA-IR and HOMA-β for each participant as the ratio of follow-up to baseline values, raised to the inverse of the follow-up time in years.

Other variables

Information on age, sex, education, smoking status (never, former, or current), and medication use was collected from examination visits and interviews. For the AWHS, anthropometric and biochemical measurements (height and weight), were certified with the International Organization for Standardization standard ISO 9001:2008. For SEN-2 weight and height were measured twice on each subject using electronic scales (model Seca 841, precision to 0.1 kg), portable extendable stadiometers (model Ka We 44 444Seca) [19]. BMI was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Serum total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was measured by spectrophotometry (Chemical Analyzer ILAB 650, Instrumentation Laboratory) in AWHS, and by colorimetric enzymatic methods using Atellica Solution® (Siemens Healthineers) in SEN-2. Physical activity for AWHS and SEN-2 (measured as Metabolic Equivalent of Task [MET]-minute/week) was assessed using the validated Spanish version [20] of the questionnaire on the frequency of engaging in physical activity from the Nurses’ Health Study [21] and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study [22]. To estimate the volume of activity performed by each participant, a metabolic cost was assigned to each activity using Ainsworth’s compendium for physical activities [23], and multiplied by the time the participant reported practicing that activity. From the sum of all activities, we obtained a value of overall weekly METs-hour. Waist circumference in cm was determined from physical exams in AWHS by using the tape measure model Gulick 2. For SEN-2, waist circumference was measured twice on each subject in standardized conditions by using flexible, inelastic belt-type tapes [19].

For AWHS, systolic blood pressure (mmHg) was measured three times consecutive using an automatic oscillometric sphygmomanometer OMRON M10-IT (OMRON Healthcare Co. Ltd., Japan) with the participant sitting after 5-min rest. While for SEN-2 was obtained thrice (1–2 min intervals) by trained personnel using the OMRON M6 model. Blood-pressure-lowering medication was collected from questionaries in both studies. C-reactive protein concentration was measured by turbidimetric immunoassay in a Beckman Coulter Image Analyzer using the manufacturer’s high-sensitivity kit in AWHS and by latex-enhanced nephelometry in SEN-2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were identically conducted in all the study populations. Geometric mean and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of blood selenium levels, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-β at baseline were reported by participant characteristics.

In cross-sectional analyses, we estimated the geometric mean ratios (GMRs) and 95% CIs of baseline HOMA-IR and HOMA-β, per two-fold increase in baseline selenium levels, as well as P values for linear trends, from linear regression models of log-transformed HOMA outcomes on log2-transformed blood selenium levels. Selenium was also modeled as tertile categories to compare the two highest with the lowest tertile of selenium distribution. To assess non-linear dose-response relationships, we used restricted cubic splines of log2-transformed selenium levels with knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of selenium distribution. The reference blood selenium value was set at 165 µg/L, since GPx activity is known to reach a plateau at serum selenium levels above 110 µg/L and serum selenium represents approximately two-thirds of blood selenium (median [interquartile range] of serum to blood selenium ratio in a subsample of our NHANES sample with available serum selenium was 66.7 [62.7, 71.6] %). The cross-sectional dose–response was replicated in NHANES, which incorporated the complex sampling design and weights with the survey package in R [24]. All models were adjusted for age (years), sex (male or female), education (≤high school or >high school), smoking status (never, former, or current), BMI (kg/m2), serum total cholesterol (mg/dL) and HDL cholesterol (mg/dL). In longitudinal dose-response analyses, we estimated the GMRs and 95% CIs of annual relative changes in HOMA-IR and HOMA-β as a smooth function of baseline selenium levels from regression models of log-transformed annual relative changes on restricted cubic splines of log-transformed selenium levels with the same knots described above. Adjustments in longitudinal models for HOMA-IR and HOMA-β annual change were similar to the cross-sectional analysis, except for further adjustment for corresponding baseline HOMA-IR and HOMA-β values. We performed a regression residual check with no clear departure from the linear regression assumptions. We also evaluated the model variance inflation factor supporting that inflation was not a problem for the selenium regression coefficient.

Finally, we conducted the Woolf heterogeneity test to compare the geometric mean ratios for HOMA-IR and HOMA-β per two-fold increase in baseline selenium levels, respectively, between the two independent studies, AWHS and SEN-2.

Sensitivity analyses. As glucose and insulin were measured with different laboratory techniques in AWHS and SEN-2, we applied recalibration methods to serum glucose and insulin measurements, using NHANES population as a common reference (i.e., external population), to make these measurements comparable between both studies (see Supplemental Methods). To assess the consistency of findings and the robustness of the results after the recalibration process, we performed sensitivity analyses using HOMA endpoints based on originally measured (i.e., non-recalibrated to NHANES) serum glucose and insulin levels. Physical activity, waist circumference, and inflammation have been proposed as risk factors for diabetes [25, 26]. Elevated blood pressure is frequently associated with other cardiometabolic potential confounders. We, thus, conducted sensitivity analyses with separate additional adjustments for physical activity, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure and blood-pressure-lowering medication, C-reactive protein, and alcohol consumption (log2-transformed g/day). In addition, considering that seafood represents one of the most abundant dietary sources of selenium [27, 28], and given that mercury (typically present in seafood) may confound the association of selenium with diabetes [29], we performed a dose–response analysis on age-stratified NHANES groups, with further adjustments for mercury.

Results

Participant characteristics

The median age in the AWHS and SEN-2 studies was 51.9 (range 42–56) and 70.0 (range 64–82) years, respectively. The proportion of men was much higher in AWHS (~95%) than in SEN-2 and NHANES (~50%) (Table 1 and Supplemental Tables S4 and S5). Geometric means (GMs) for blood selenium were 141.6 and 116.8 μg/L in AWHS and SEN-2, respectively (Table 1). For HOMA-IR, the GMs were 1.9 and 2.0 in AWHS and SEN-2, respectively, and for HOMA-β were 71.1% and 73.4%, respectively (Table 1). Descriptive results for original (non-calibrated) HOMA endpoint levels are shown in Supplemental Table S4. HOMA-IR and HOMA-β were higher in participants with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and low HDL cholesterol in AWHS and SEN-2 (Table 1). In age-stratified NHANES replication populations, the median age was 48.8 years for middle age (range 40–59) and 69.3 years (range 60–80) for older participants. Descriptive information for age-stratified NHANES is shown in the Supplemental Material (Supplemental Table S5).

Association of selenium with HOMA-IR and HOMA-β in middle-aged and older adults

In cross-sectional association analysis, the GMRs (95% CIs) of HOMA-IR levels by doubling blood levels of selenium were 1.09 (1.01, 1.19) in AWHS and 1.13 (0.98, 1.31) in SEN-2. The corresponding GMRs (95% CIs) of HOMA- β levels were 1.15 (1.06, 1.24) in AWHS and 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) in SEN-2 (Table 2). In evaluations of the cross-sectional dose-response, baseline blood selenium levels were mostly positively and monotonically associated with baseline HOMA-IR and HOMA-β among middle-aged participants (AWHS and NHANES participants aged < 60 years) (Supplemental Fig. S1). In older ages (SEN-2 and NHANES participants aged ≥ 60 years), we observed a positive association between higher selenium levels and an increased in HOMA-IR, becoming flat at higher exposure doses. However, selenium was not associated with HOMA-β (Supplemental Fig. S2).

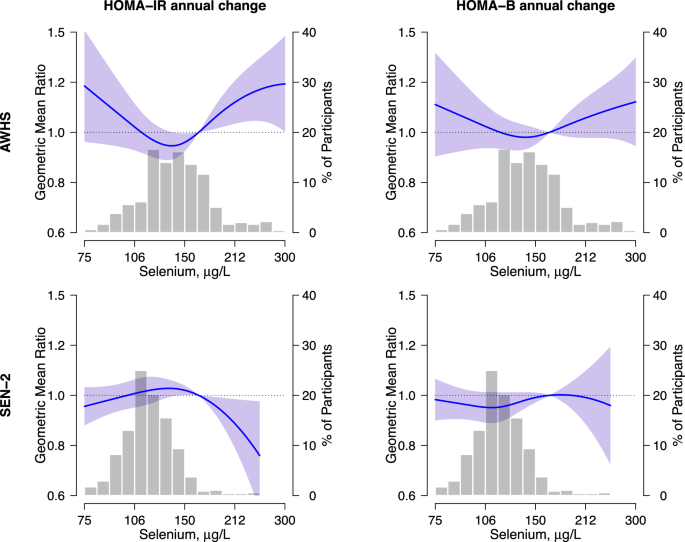

For the longitudinal analysis, the dose response showed non-linear associations between blood selenium levels and HOMA endpoints in AWHS, in which the association was positive above 150 μg/L of blood selenium (Fig. 1). In SEN-2, the corresponding association was not positive for HOMA-IR, and null for HOMA- β (Fig. 1).

Abbreviations: AWHS Aragon Workers Health Study, SEN-2 Seniors ENRICA-2. Panels represent the longitudinal dose–response relationships of blood selenium levels with annual relative changes in HOMA-IR (left) and HOMA-β (right) in AWHS participants (top, N = 571) and SEN-2 participants (bottom, N = 603). Lines (shaded areas) represent adjusted geometric mean ratios (95% confidence intervals) of annual relative changes in HOMA outcomes estimated from regression models with restricted cubic splines of log2-transformed selenium levels with knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles. The reference value was set at 165 µg/L of selenium distribution. All models were adjusted for age, sex, education (≤high school or >high school), smoking status (never, former, or current), body mass index, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and baseline HOMA-IR or HOMA-β (log-transformed). Histograms in the background represent the selenium distributions in each study at the baseline visit.

The Woolf heterogeneity P-value across middle-aged and older study populations was 0.53 for HOMA-IR and 0.05 for HOMA-β models (data not shown).

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analysis of non-standardized HOMA-IR and HOMA-β measures, the results were consistent with those obtained using the recalibrated HOMA values (Supplemental Table S6). The findings remained basically unchanged after separately adding other adjustment variables (physical activity, blood pressure variables, C-reactive protein, and alcohol intake) into the adjustment models (data not shown), except for the HOMA-IR models in the SEN-2 study [GMRs (95% CI) for two-fold increase in blood selenium was 1.17 (1.02, 1.35)] after including waist circumference as a covariate (Supplemental Table S7). In NHANES, additional adjustments for blood mercury and race did not substantially change the shape of the dose–responses (data not shown).

Discussion

Increasing blood selenium levels were cross-sectionally associated with increased HOMA-IR and HOMA-β in middle-aged adults. In older adults, we observed a similar, but not so strong, positive linear trend, for HOMA-IR, but not for HOMA-β, which in flexible dose–responses stabilized at the highest selenium range. While the levels of selenium exposure in our study populations (AWHS and SEN-2) were different compared to those observed in the replication study population (NHANES), possibly due to differences in selenium soil content and supplementation intake, we observed fairly consistent findings. The longitudinal analysis showed a non-linear dose–response, with positive associations for both HOMA endpoints at blood selenium levels above ~150 μg/l in AWHS but not in SEN-2.

In this study, blood selenium levels in both Spanish populations were substantially lower than those in the United States general population. Selenium-containing supplements have gained popularity and easy accessibility to consumers, especially in the United States, despite a dearth of evidence supporting their effectiveness in preventing disease [30]. Although in NHANES, we only include those participants without dietary supplement intake, we cannot rule out potential miss-classification bias because the information on supplement intake was self-reported. In the Spanish study populations, we observed that middle-aged participants in AWHS have higher blood selenium levels (geometric mean 141.60 µg/L) compared to older SEN-2 participants (geometric mean 116.78 µg/L). Selenium status was reported to decrease in an age-dependent manner, supporting that selenium requirements increase with age [31, 32]. The necessary intake of dietary selenium to maintain biological functions is understood to depend on selenium-demanding situations, which are more common at older ages [22, 33]. Also, omics approaches applied to animal models have detected changes in genetic expression and proteomics associated with selenium status in pathways linked to aging and age-related illnesses [31, 34]. However, we cannot completely discard that the observed differences between blood selenium concentrations in both Spanish populations are partly due to factors beyond exposure such as potential differences in laboratory methods.

Epidemiological studies of selenium-related diabetes display, generally, controversial results. A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials found a null association between selenium supplementation and HOMA-IR [35]. Contrary to our results, in 2420 participants without diabetes from the CODING study (Newfoundland population, mean age 42), selenium intake was negatively correlated with HOMA-IR [36]. However, this correlation was attenuated and no longer statistically significant with selenium intake above 1.6 μg/kg/day [36]. Nevertheless, the comparison with our results is not clear because the CODING study used a food frequency questionnaire to evaluate selenium exposure, not biomarkers. On the contrary, in a case-control study from Taiwan (N = 1165, mean serum selenium and age were 96.34 μg/L and 65 years, respectively) and in a cross-sectional analysis in NHANES 2013–2018 (mean age 47.7), the authors reported a positive association between serum selenium levels and HOMA-IR [12, 37], both in men and women. Furthermore, a recent Mendelian randomization analysis of genetically predicted selenium with measured fasting insulin and HOMA-IR was also consistent [38]. Nonetheless, unlike our study, the possible differential association by age and potentially non-linear dose–response was not evaluated in previous studies.

At the highest selenium range, the positive association of blood selenium with insulin resistance is supported by experimental studies that point to a role of redox unbalance in the dysregulation of glucose homeostasis [3, 39, 40]. Selenium, as a component of antioxidant proteins, such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx), contributes to the reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [41]. However, selenium excess can induce selenoprotein saturation and unspecific bounding of selenium to circulating proteins, possibly leading to a pro-oxidant effect, and insulin resistance [39]. In the Hortega Study, a Spanish study population, plasma selenium levels above 110 µg/L were associated with GPx-dependent oxidative stress biomarkers [42]. In our study, we observed changes in the longitudinal dose-response trend at levels of blood selenium above ~150 µg/L. This result supports the idea that excessively high exposure levels may reverse the beneficial effects of selenium on cellular redox mechanisms. In addition, excess selenoprotein P has been shown to impair insulin signaling and pancreatic β-cell function and is associated with type 2 diabetes in in-vitro and in observational studies [6, 43].

Animal studies suggest that not only selenium excess but also deficiency may be positively associated with type 2 diabetes [44]. Some epidemiological studies also point to non-linear associations between selenium exposure and endpoints such as oxidative stress biomarkers [42], and all-cause and cancer mortality [45]. While the longitudinal association was clearly non-linear for both HOMA-IR and HOMA-β in our aged-middle study populations, as expected, the corresponding association was fairly linear in our cross-sectional analysis. Other epidemiological studies did not find such U-shaped response with insulin-resistance-related endpoints [46].

For HOMA-β, we found a positive association with blood selenium levels in middle-aged but not in older adults. We propose that, at middle age, increased β-cell function may partly be a response to the insulin resistance state induced by selenium, in which glucose levels rise, and β-cells try to compensate by releasing more insulin. In older people, β-cells may begin to deteriorate and be less functional, thus not keeping glucose levels low enough, leading to diabetes [47]. Experimental studies have shown the upregulation of cell cycle inhibitors, with a decline in the proliferative and regenerative capability of β-cell in older age [48]. Indeed, the accumulation of DNA mutations with aging is associated with the disturbance of transcriptional and protein homeostasis leading to an increase in oxidative stress and ROS in pancreatic cells [47]. Also, it has been observed that HOMA-β indexes depend quadratically on age, decreasing with elderliness [49], supporting our hypothesis. Some in vitro studies in pancreatic cells, however, show increased insulin release with selenium supplementation [50]. It is, thus, also possible that, at low doses, there is a component of a protective effect of selenium on β-cell. The very few epidemiologic studies that have previously evaluated the association between selenium exposure and pancreatic β-cell function [35, 38] show conflicting results, which is not surprising since they include participants with potentially heterogeneous selenium status, do not perform stratified results by age, and use different biomarkers of selenium exposure (toenail and serum selenium levels).

Our study has several limitations. Selenium biomarker concentrations may be altered in the presence of inflammation, a central mechanism in insulin resistance. While tight adjustment of overall chronic inflammation is difficult, in sensitivity analysis adjustment for serum C-reactive protein in AWHS and SEN-2 did not change the results (data not shown), making it less likely that residual confounding by inflammation can completely explain our findings. Importantly, it is well-known that whole blood concentrations are more stable to inflammation compared to other exposure biomarkers such as serum [51]. In addition, the proportion of women in AWHS was considerably low, so results may not be completely generalizable to middle-aged women. The dose-response associations, however, were consistent in NHANES, which is a representative sample of the general population in the US that includes both men and women. Another limitation relates to the fact that we do not have available information regarding ethnicity in the Spanish populations. Nonetheless, the findings were consistent in NHANES, which is a more ethnically diverse population compared to the Spanish population (data not shown). Finally, in our data, both HOMA indexes increased with BMI in the three study populations, which was previously reported [49] and is plausible due to the close link between adipocytes and insulinemia. While to avoid potential residual confounding by adiposity we included BMI as a covariate in all association analysis models, as in other observational studies, some residual confounding cannot be completely discarded. We conducted, nonetheless, several sensitivity analyses, including adjustment for waist circumference, but also physical activity, blood pressure variables, alcohol intake, and mercury, with essentially similar findings, suggesting that those potential confounders are not relevant to our data.

The strengths of this study include the use of data from three study-populations with high-quality procedures of data collection, processing, and laboratory analysis of biological samples. In addition, despite serum glucose and insulin having been measured in different laboratories, we made an effort to ensure the comparability of the results using a representative US population as the reference population. Similar results from original and recalibrated data support that the observed differential associations by age are not due to specific participant characteristics or between-laboratory variations in glucose or insulin measurements. Moreover, typical limitations of cross-sectional studies were overcome by a longitudinal analysis.

In conclusion, blood selenium exposure was positively associated with insulin resistance and β-cell function in middle age but not in older adults, especially for β-cell function. Thus, our results suggest that selenium-associated increased insulin resistance may induce compensatory β-cell function, which is impaired with age. Additional studies, however, are needed to confirm the association between selenium and insulin resistance in older adults. Despite the potential limitations, our work points to age-associated mechanisms of selenium on the onset of type 2 diabetes, which could lead to precision strategies for type 2 diabetes prevention and control depending on age and selenium biomarkers.

Responses