Genetic markers of early response to lurasidone in acute schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a devastating psychiatric disorder with a typical onset during adolescence. Antipsychotic drugs (APDs) are indicated for the treatment of patients with SCZ or schizoaffective disorder who are experiencing their first-psychotic episode, or recurrence of positive symptoms. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) [1] and the British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) [2] guidelines stated that antipsychotic treatment can improve the positive and negative symptoms of psychosis and leads to remission of symptoms. Based on the latest systematic literature review of English-language clinical practice guidelines, there was strong consensus on antipsychotic monotherapy [3]. There are two main classes of drugs, that is, first- and second-generation antipsychotics (FGA and SGA) that are used to treat SCZ [3]. SGAs are usually favored due to the lower events of adverse effects, such as extrapyramidal effects, tardive dyskinesia, and relapse [4].

Lurasidone is a widely used SGAs, whose dominant pharmacologic profile is potent serotonin (5-HT)2A inverse agonism, 5-HT1A partial agonism, 5-HT7 antagonism [5] and weaker D2 receptor antagonism, a shared feature of SGAs [6]. Lurasidone is approved for the treatment of SCZ not only in adults but also in adolescents ≥13 years of age [7]. Lurasidone has been shown to be superior to placebo in improving psychopathology in acutely psychotic patients with SCZ in short-term studies as well as in long-term studies. In comparison with other SGAs, a lower incidence of cardiometabolic side effects has been observed with lurasidone [8]. The neuroprotective effects of lurasidone has been reported in ameliorating the neurodegenerative effects of psychosis [9]. Improvement in psychopathology in treatment resistant SCZ with lurasidone was also reported [10].

There is marked variability in the extent and time course of response to APDs in these phases of illness, which are associated with increased risk for suicide, disruption of work and school function, and increased burden on family and caregivers [11]. During this phase, clinicians consider increasing dosage, parenteral administration, switching to another APD, adding second APD, adjunctive medications, or somatic treatments, e.g. electroconvulsive therapy. However, switching to another APD prior to completion of a six-week treatment may misidentify patients as insufficient responders to that treatment.

A comprehensive review of the time course of response to APDs of 9460 patients with SCZ from 34 studies identified a large subgroup who responded by two weeks [12]. Kishi et al. further added the evidence that there was a significant correlation between early treatment response at week two and response at week six using 1115 adults with acute SCZ of Japanese population [13]. As clinical response is strongly influenced by genetic factors which are related to the pathogenesis of SCZ [14,15,16]. For example, we previously reported that week six response were associated with genes including synaptic adhesion molecules and scaffolding proteins [15]. Some genes may uniquely contribute to earlier response to APDs such as week one and two. Identification of genetic biomarkers associated with the early response to APDs can be of great help in both clinical research and clinical practice, as it can lead to optimizing the treatment time for a patient, avoiding premature discontinuation. We, therefore, conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) looking for genetic markers associated with early response to lurasidone.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

All eligible subjects with DNA who participated in two six-week randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter registration trials of lurasidone were included [17, 18]. The subjects were acutely psychotic inpatients with SCZ and details were described in elsewhere [15]. Briefly, hospitalized male and female patients 18–75 years of age who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for a primary diagnosis of SCZ (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), were enrolled. Patients were also required to have an illness duration of at least 1 year and were currently experiencing an acute exacerbation of psychotic symptoms (lasting ≤ 2 months). Additional criteria for eligibility included a Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) score ≥ 4 (moderate or greater) and a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score ≥ 80, including a score ≥ 4 (moderate) on two or more of the following PANSS items: delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinations, unusual thought content, and suspiciousness [9, 10]. Patients were excluded if they had an acute or unstable medical condition, evidence of any other chronic disease of the central nervous system, history of resistance to treatment neuroleptics, alcohol or other drug abuse/dependence within the past 6 months, or evidence of a severe chronic movement disorder [9, 10]. Patients were also excluded if they had been treated with clozapine during the 4 months prior to enrollment or had received depot neuroleptics. Eligible patients were tapered off psychotropic medications prior to 3 to 7 days, single-blind, placebo run-in period [9, 10]. One of the trials randomized patients to lurasidone 40 mg/day or 120 mg/day, or placebo [17]. The other randomized patients to treatment with lurasidone 40, 80, or 120 mg/day, or placebo [18]. Change in the PANSS total scores (Δ) were the primary measure of efficacy. Response was defined at ≥ 20% improvement in PANSS total between baseline and last observation. The proportions of responders were identical in both clinical trials (see Table 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects are listed in Table 1.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants or their legal guardians provided written informed consent for study participation, including genetic analysis [17, 18]. The protocol was approved by the ethical committees of all participating sites and all methods were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [17, 18].

Evaluation of treatment response

The primary measure of efficacy, ΔPANSS-Total, was the difference between baseline and week one, two, or four PANSS total scores. We combined data from both studies and all doses because response in these studies was not dose-dependent [15, 17, 18]. It should be noted that in a subsequent trial with similar design, the responder rate using lurasidone at 160 mg/day was 79% (p = 0.018), significantly greater than that at 80 mg/day (65%) [19].

Genotyping and data analysis

Genotyping has been described in detail elsewhere [15, 16]. Briefly, DNA samples of patients from the two clinical trials (total N = 171) were genotyped using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. No imputation was applied, and all reported SNPs were directly genotyped. Quality control (QC) for genotype data was conducted to exclude single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.05, genotyping rate < 0.95, and significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE, p < 0.0001). European-ancestry origin was verified by principal component analysis (PCA) using PLINK 1.9 [20, 21]. This QC step left a total of 859,216 SNPs for the final GWAS analysis. To archive the statistical power of 0.8 to detect the genetic marker of genotype relative risk is 5.5, more than 150 cases are needed. PLINK 1.9 linear regression model was used to test the association between the common genetic variants (MAF > 0.05) and ΔPANSS-Total, controlling for age, gender, drug dosage, and three principal components from genotypes to control for population stratification [22]. Associations were conducted separately for treatment and placebo groups. Baseline psychopathology was not included in the final linear regression model because it did not significantly contribute to the full model. Gene annotation and gene-based analysis were conducted using MAGMA version 1.06 [23] integrated into FUMAGWAS (http://fuma.ctglab.nl/), using the summary statistics of the linear regression. Quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots were generated on the basis of allele-wise or gene-wise analysis that passed QC. Effect sizes were calculated with QUANTO 1.2.4 [24]. Their risk for SCZ were also checked using the SCHEMA browser (https://schema.broadinstitute.org/gene/) [25].

eQTL analysis with Braincloud, Braineac, and LIBD eQTL browser

Functional annotation was conducted including cis expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTL) from ScanDB, Braineac, Braincloud, and the LIBD eQTL browser. Only gene expression associations with p < 2.94 × 10−6 were considered as eQTL. Details for the eQTL database are available in supplementary material.

Tissue and pathway enrichment analysis of the mapped genes from the top associated genetic loci

GENE2FUNC from FUMAGWAS was used to identify the type of tissues which the top mapped genes prioritized by the unadjusted p-value (< 10−5) from the SNP-wise association were enriched, and to test for overrepresentation of those genes in the set of genes from predefined pathways. False Discovery Rate (FDR) by Benjamin-Hochberg method was conducted with adjusted p-value cutoff = 0.05; minimum number of overlapped genes with gene-sets was set as 3. We utilized the average of normalized expression data from GTEx V6 53 tissue types, which allows comparison of gene expression data across tissue types. Top genes were also tested against each of Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) sets using the hypergeometric test. Bonferroni corrected p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant enrichment for up-regulated or down-regulated DEG sets. Pathway enrichment analysis was also conducted by the hypergeometric testing to identify overrepresented genes of interested in any of the specific pathway related gene sets available in Gene Ontology (GO). The significance of enriched pathways was corrected per category with the Benjamin-Hochberg (FDR) test.

Results

None of the associations reached genome-wide significance as predictors of ΔPANSS-Total at weeks one, two, or four due to the limited power from our small sample size; therefore, we report here the SNP associations surpassing the suggestive threshold of p < 1.0 × 10−5 in patients with SCZ (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1).

Week one genomic markers of potential interest

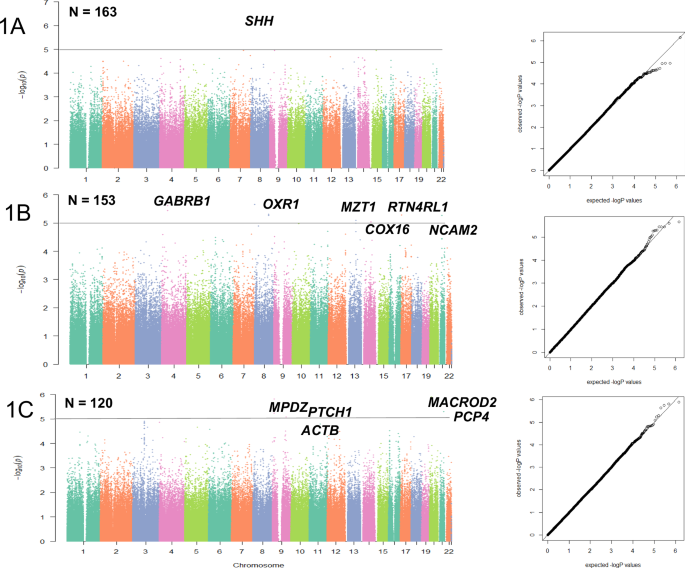

As shown in Manhattan plot (Fig. 1A), the top SNP for week one improvement was rs6459950 (p = 7.05 × 10−7), located on Chromosome 7q36.3, near SHH, the sonic hedgehog gene. In patients with SCZ with A/A genotype, who were predicted to have the decreased expression of SHH, was possibly associated with diminished lurasidone response (Supplementary Fig S1A). The effect size of the minor allele was ({{{rm{R}}}}_{{{rm{G}}}}^{2}=0.1337), indicating that 13.37% of the score change by lurasidone may be attributable to this SNP.

Manhattan plots and QQ plots for GWAS results related to Δ change in PANSS-Total at week one (A), two (B), and four (C). Mapped Genes with raw p-value < 1 × 10−5 were annotated. There was no evidence for systematic inflation of genome-wide test statistics, as assessed by the genomic inflation factor (λ), which is equal to 1.00 for all time-points.

eQTL analysis showed that rs6459950, possibly associated with diminished response to lurasidone at week one, significantly affected the expression of SHH in post-mortem brain tissue from SCZ subjects of European ancestry (Table 2, Supplementary Fig S1A). Patients with SCZ harboring the A/A genotype of rs6459950 were predicted to have decreased expression of SHH compared to those with A/T or T/T genotype, in an allelic dosage manner (Supplementary Fig S1A). According to scanDB, a blood-based database for QTL analysis, rs6459950 significantly affects the DNA methylation status of an upstream CpG island, cg27481428 (p = 8.12 × 10−9).

Week two genomic markers of potential interest

The genetic signals nominally associated with response to lurasidone at week two was rs7435958, an intronic SNP within the GABRB1, encoding the GABAA receptor β1 subunit (p = 2.47 × 10−6), and the effect size of the minor allele was ({{{rm{R}}}}_{{{rm{G}}}}^{2}=0.1527) (Fig. 1B).

In eQTL analysis, rs7435958 was predicted to moderately affect the gene expression of GABRA4, GABRA5 and GABRG2 (p = 0.04271, 0.00604, 0.0447, respectively (Braincloud). They encode extra-synaptic GABAA receptor subunit α4, α5 and γ2. Braineac supported one of the eQTLs (p = 2.8 × 10−4 for GABRA4, Supplementary Fig S1B). Patients with SCZ harboring C/C genotype of rs11940530, a proxy SNP of rs7435958 (r2 = 1, D’ = 1 for the linkage disequilibrium (LD)), was predicted to have increased expression of GABRA5 and GABRA4, had less improvement after week two lurasidone treatment.

Week four genomic markers of potential interest

The putative genetic signal for week four response to lurasidone was rs17812574, an intronic SNP within the MACROD2, p = 1.27 × 10−6, and the effect size of the minor allele was ({{{rm{R}}}}_{{{rm{G}}}}^{2}=0.17) (Fig. 1C). The second hit was rs10120217 (p = 1.54 × 10−6, ({{{rm{R}}}}_{{{rm{G}}}}^{2}=0.20)). This SNP was close to MPDZ, which encodes a multi-PDZ protein. The third hit was rs16998897 (p = 1.79 × 10−6, ({{{rm{R}}}}_{{{rm{G}}}}^{2}=0.3397)), an intronic SNP within PCP4, which encodes the Purkinje cell protein 4 (Table 2). The fourth hit was rs10512247 (p = 2.33 × 10−6, ({{{rm{R}}}}_{{{rm{G}}}}^{2}=0.1521)), an intronic SNP within PTCH1, which encodes Patched 1(Fig. 1C).

In eQTL analysis, rs17812574 was predicted to affect the gene expression of MACROD2 in thalamus (p = 1.9 × 10−4, Supplementary Fig S1C). Patients with SCZ harboring C/C genotype of rs17812574, who were predicted to have decreased expression of MACROD2 showed a diminished response to lurasidone relative to those with T/C genotype. rs10512247 was predicted to influence the gene expression of PTCH1 in temporal cortex (p = 1.9 × 10−3, Supplementary Fig S1D). Patients with SCZ harboring T/T genotype of rs10512247 was predicted to have decreased expression of PTCH1 and had a better response to lurasidone.

Tissue and pathway enrichment analysis of the mapped genes from the nominally associated genetic loci

Eleven mapped genes of putative association with early response to lurasidone (SHH, GABRB1, OXR1, RTN4RL1, NCAM2, MTZ1, COX16, MACROD2, MPDZ, PCP4, PTCH1, ACTB) and ~17,000 background genes mapped by MAGMA were the input for tissue type and pathway enrichment analysis. The heatmap with hierarchical clustering at gene level (row-wise) or tissue level (column-wise) showed that the top genes were enriched in multiple brain regions (Supplementary Figure S2). The top-tier enriched tissue type with up-regulated gene sets were the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, p = 0.014) and frontal cortex Brain Area 9 (p = 0.035), both of which survived Bonferroni correction.

Pathway enrichment analysis was further performed by hypergeometric testing to determine if genes of interest were enriched in specific pathway-related gene sets. The top enriched GO biological processes terms were “GO central nervous system (CNS) Neuron Differentiation” (pBH = 0.001), “GO CNS Nervous System Development” (pBH = 0.002), and “GO Neurogenesis” (pBH = 0.004).

Discussion

Although none of the variants reached genome-wide significance due to the very limited sample size, this study is the first to observe the genetic signals of potential interest in the early clinical response to lurasidone with the p-value < 10−5, the threshold often used for discovery of preliminary associations of interest for APDs response [14]. Suggestive biological markers of early response to lurasidone, may be related to processes such as initiation of neuronal differentiation and neurogenesis (week one, four), extra-synaptic GABAA receptor signaling (week two), modulation of neurotransmitter and calmodulin activity (week four). Pathway analysis further implicated the possible involvement of neuronal differentiation and neurogenesis in the antipsychotic action of very early response phase. Tissue enrichment analysis suggested that the ACC may be relevant brain region for the early antipsychotic action of lurasidone. This study complements the study on potential genetic biomarkers that may be associated with treatment response after six weeks in acute psychotic patients with SCZ using the same population from two clinical studies [16].

Neurogenesis and SHH signaling in early antipsychotic effect

This study suggested the possibility that the SHH signaling might be involved in the antipsychotic action of lurasidone, especially at week one. There is extensive evidence that lurasidone stimulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) secretion [26], a key factor in neurogenesis [27]. Treatment with lurasidone has been shown to increase serum BDNF levels in acutely psychotic patients with SCZ to date [28]. Interestingly, SHH signaling has a critical role in the initiation of the neurogenesis through activation of the BDNF-TrkB signaling pathway [29]. Given the fact that the SHH is important in neurogenesis on GABAergic and dopaminergic neurons [30,31,32], lurasidone might exert its antipsychotic action by stimulation of neurogenesis for these neurons through the SHH signaling. Notably, the activity of the SHH signaling is regulated by G protein-coupled receptors such as Dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2), 5-HT7 receptor (HTR7), and 5-HT1A receptor (HTR1A), the main targets of lurasidone [33]. Based on the results from the blood-based database for QTL analysis, rs6459950 significantly affected the DNA methylation status of an upstream CpG island, suggesting this SNP may also influence on gene expression of SHH through an epigenetic mechanism.

Regarding the possible week four genetic marker, rs10512247 near PTCH1, PTCH1 is a specific receptor for SHH, the putative gene possibly associated with week one response [34]. Considering the fact that clozapine and haloperidol were also shown to regulate the SHH pathway [34], suggesting that the SHH signaling might be a shared target of antipsychotic action to ameliorate psychotic symptom.

Extra-synaptic GABAA receptor signaling and early antipsychotic effect

Although lurasidone has little affinity for the GABAA receptor, Patients with SCZ predicted to have increased expression of GABRA5, GABRA4, and GABRG2 showed relatively poor response to lurasidone in this study. Interestingly, among the GABAA receptors, the GABAA receptor genes nominally associated with the early response were enriched in extra-synaptic compared to synaptic GABAA receptors [35]. There is accumulating evidence that inhibiting α5 subunits-containing extra-synaptic GABAA receptors in the hippocampus can enhance cognition [36,37,38] and are considered as promising therapeutic targets for treatment of SCZ and other psychiatric disorders [35, 39,40,41]. In the light of GABAA signaling and neurogenesis, it has been demonstrated that migrating cortical interneurons express functional GABAA receptors [42, 43]. Considering the fact that the excessive DRD2 activation during psychosis may decrease GABAergic neuronal migration [44, 45], lurasidone might rescue this process.

Calmodulin signaling and week four response

The top week four marker of potential interest was located at MACROD2 which encodes Mono-ADP Ribosylhydrolase 2. Interestingly, MACRODs has been shown to influence brain volume in SCZ [46]. Reduction of the brain volume in patients with SCZ was well studied as a biological imaging marker. Based on the meta-analysis over 18,000 subjects, using the sample of antipsychotic-naive patients with SCZ (n = 771), volume reductions in caudate nucleus and thalamus were shown to be existed before the stating treatment with APDs [47]. A GWAS of MRI-derived temporal lobe volume measures from 729 subjects with European ancestry found that a SNP in MACROD2 reached genome-wide significance (p = 7.94 × 10−12) [46]. In addition, rare copy number variants in MACROD2 have been reported in a multiplex family of SCZ [48]. These notions support the possibility that MACROD2 may be involved in the pathophysiology of SCZ.

Another week four genetic marker of potential interest was mapped to MPDZ which has been shown to interact with multiple neurotransmitter receptors, including the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, as well as 5-HT2A receptors [49] and DRD2 [50], key pharmacological targets of lurasidone. MPDZ forms a complex with CaMKII, a hub signaling protein. PCP4 is a brain specific modulator of calmodulin activity [51], and the calmodulin is a key protein in CaMKII signaling, which is a major basis for the ability of neurotransmitters released by lurasidone and other antipsychotic drugs to regulate gene expression [52].

Anterior cingulate cortex and antipsychotic response

Tissue enrichment analysis suggested that the genes of potential interest in early response to lurasidone were enriched in brain regions, especially the ACC and frontal cortex. The ACC is a part of the limbic system and receives inputs from orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala which receive projections from ventral striatum [53]. Several imaging studies have shown state-dependent changes in functional interactions between subcortical and prefrontal regions during antipsychotic treatment [54] and reported that the ACC was an important target region of APDs [55]. Lately, using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) in 42 drug-naive first-episode patients with SCZ, non-responders to the treatment with risperidone had higher glutamate level in ACC than responders, suggesting that the ACC is relevant lesion for antipsychotic response [56]. Another group has also replicated the finding that high glutamate levels in ACC were associated with poor response to APDs in 89 first-episode patients with SCZ [57]. In the future, it might be interesting to examine whether the interaction of the putative associated genes observed in this study are associated with glutamate levels in the ACC. We have previously reported a case with an exceptional response to risperidone, which was related to specific increase in grey matter in the ACC [58] may support that the ACC is of interest for the treatment response to APDs.

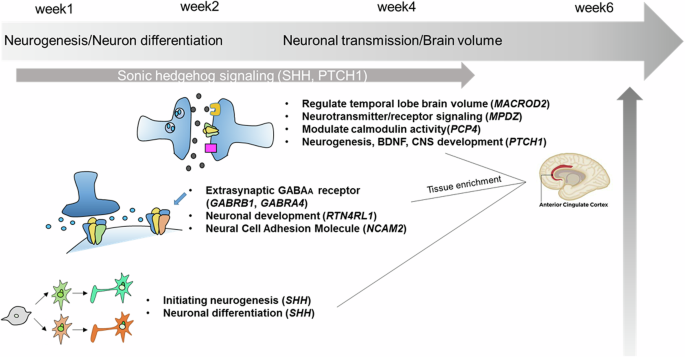

Taken together with the observed genetic markers of potential interest, one of the possible mechanisms for antipsychotic action of lurasidone during early response phase might be hypothesized as below. Acute psychotic status of the patients with SCZ possibly due to its hyper dopaminergic status may inhibit adult neurogenesis [59] and sometimes it may lead the reduction of brain volume [60]. The pharmacological action of lurasidone might stimulate the SHH signaling to initiate neurogenesis to rescue the neuronal damages. Because newborn neurons require expression of extra-synaptic GABAA receptor for migration, it is possible to speculate that extra-synaptic GABAA receptors might be associated with treatment response after two weeks of treatment. In addition, at four weeks, owing to the expression of PTCH1, a specific receptor for SHH, SHH signaling become functional and the expression of MPDZ, which interacts with various neurotransmitters, might help the new neurons make synapses. The results of pathway analysis may support the importance of neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and CNS development in early antipsychotic action. A schematic diagram illustrates possible time-dependent mechanisms of the antipsychotic action of lurasidone modestly disclosed by the GWAS on early response (Fig. 2).

Schematic diagram illustrates putative mechanisms of early action for the antipsychotic effect of lurasidone based on the top annotated genes of potential interest for further studies. Acute psychotic status may inhibit adult neurogenesis due to its hyperdopaminergic status. Lurasidone might stimulate the SHH signaling to initiate neurogenesis to rescue the neuronal damages. it is possible that extra-synaptic GABAA receptors might be associated with treatment response after two weeks of treatment because newborn neurons require expression of extra-synaptic GABAA receptor for migration. At four weeks, owing to the expression of PTCH1, a specific receptor for SHH, SHH signaling become functional and the expression of MPDZ, which interacts with various neurotransmitters, might help the new neurons make synapses. The results of pathway analysis may support the importance of neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and CNS development in early antipsychotic action.

Limitations

There are several limitations needed to be aware of in this study. First, the sample size is extremely small and this study was underpowered based on the power calculation of GWAS [61]. Considering that the effect size of genetic markers is assumed to be larger in pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics, that is, odds ratios of > 5–10 [62], the required sample size was more than 200 cases to archive statistical power of 0.8 to detect the genetic marker of genotype relative risk is 5.0, if the prevalence of SCZ was set as 0.01 and disease MAF was set as 0.05. Although nominal association was only observed in the SCZ group but not in the placebo group, the sample size of placebo group was only one third in size of the lurasidone group, so attention should be paid to understand the placebo results, this was also underpowered. Clinical trials typically have much smaller sample size compared to large-scale biobank studies. This makes it challenging to detect subtle genetic effects due to the polygenicity of drug efficacy; Due to strict enrollment criteria, the findings from pharmacogenomic studies may not generalize to real-world patient population with greater genetic and phenotypic diversity, as well as varied duration of treatment for evaluation of short-term or long-term drug efficacy. Potential selection bias may occur due to the stringent ethical and regulatory requirements for enrollment, as well as informed consent for both genetic and clinical data collection. However, clinical trials provide a controlled environment where clinical variables such as drug dosages, treatment regiments, and outcome measures are prospectively designed and standardized. This controlled environment may reduce variability and confounding factors, allowing for more precise assessment of pharmacogenomic associations. High-quality phenotypic data enhances the accuracy and reliability of the association studies. With specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for enrollment, this prospective design warrants a more homogenous study population and less genetic/environmental heterogeneity, thus may enhance the statistical power to detect biologically relevant findings. Prioritizing the variants using integrated bioinformatics approaches, such as eQTL and pathway/tissue enrichment analysis, may also help to understand the function of suggestive signals. Second, caution is needed to interpret the results when applied to other ancestries. The results could be applied only to Caucasians. Third, replication of the findings and gene targeted studies with a larger cohort are essential to pursue the possibility of genomic markers observed in this study. Forth, in the clinical perspective, the patients were not treatment naïve when they were enrolled in the two placebo-controlled trials. Other than genetic background for the treatment response to APDs, the adherence of the patients preceding the enrollment may have influenced on the clinical course of SCZ. Fifth, in the linear regression model, the number of previous medications had better to be included as a variable to obtain clearer results. Sixth, it is clinically important to clarify that which genetic markers were possibly associated with the psychopathologies such as positive symptoms and/or negative symptoms. Further studies focusing on the improvement in each psychopathology would be of great help to understand the biological basis on pathophysiology of SCZ.

Conclusions

We conducted the first GWAS of very early response to lurasidone in the patients with SCZ of European ancestry. Although genome-wide significance was not reached with the limited samples size, functional evaluation with eQTL and pathway/tissue enrichment analyses suggested the possibility that initiation of neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation through SHH signaling and extra-synaptic GABAA receptor might be of potential interest for further studies. The findings derived from the pharmacogenomic study using clinical trial data are still valuable because the prospectively designed and strictly controlled environment may enhance the accuracy and the reliability of the pharmacogenomic associations. Integrating findings from both clinical trial-base and biobank-based pharmacogenomic studies can provide a more comprehensive understanding of genetic risk factors on drug responses and facilitate the translation of precision medicine into clinical practice.

Responses