An exploratory network analysis to investigate schizotypy’s structure using the ‘Multidimensional Schizotypy Scale’ and ‘Oxford-Liverpool Inventory’ in a healthy cohort

Introduction

Schizotypy as a multidimensional construct

Schizotypy is conceptualised by Kwapil & Barrantes-Vidal (2015) as a spectrum of personality traits that manifest in unusual cognitive, emotional, and behavioural patterns1. These traits exist to varying degrees across the general population, ranging from subtle and adaptive expressions, such as behavioural peculiarities (i.e. eccentric traits) or creative thinking, to more pronounced and maladaptive forms that may evolve into clinically significant conditions2,3,4. At the extreme, these traits can align with clinical diagnoses such as schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) or schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD). Our view aligns with this conceptualisation, as we also consider schizotypy to span a continuum from subclinical traits to more severe forms linked to clinical diagnoses.

SPD arises when schizotypal traits become predominant and pervasive, significantly impacting an individual’s social functioning, behaviour, and overall personality5. SPD is characterised by persistent deficits in interpersonal relationships, cognitive-perceptual distortions, and eccentric behaviours. This effectively positions SPD as an intermediate stage between schizotypy as a personality construct and more severe clinical manifestations seen in SSD6,7,8.

SSD, which includes schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and other related conditions, represent the most severe clinical manifestations associated with schizotypy. SSD are marked by psychosis, severe cognitive disorganisation, and significant functional impairment9. Given that schizotypy is considered a latent risk factor or precursor to SPD and SSD, it is crucial to study schizotypy in order to better understand the aetiology and development of psychotic disorders10.

Schizotypy exists as a multidimensional construct comprising three primary dimensions, each reflecting distinct aspects of the disorder that vary along the continuum11,12,13,14,15. These dimensions are:

-

1.

Positive schizotypy: this dimension involves traits like unusual perceptual experiences, magical thinking and paranoid ideation, which reflect a heightened sensitivity to external stimuli and cognitive distortions. These characteristics parallel the positive symptoms of SSD, such as hallucinations and delusions, linking schizotypy to the early cognitive features of psychosis14.

-

2.

Negative schizotypy: defined by traits such as emotional flattening, social withdrawal and anhedonia, this dimension mirrors the negative symptoms of SSD, including difficulties in motivation, diminished emotional expression, and impaired interpersonal functioning. These negative traits are often associated with the more enduring and socially debilitating aspects of schizotypy15,16.

-

3.

Disorganised schizotypy: this dimension captures cognitive and behavioural disorganisation, such as incoherent thinking and speech and challenges in goal-directed behaviour. Disorganised schizotypy is closely tied to impairments in executive functioning and the ability to regulate thought processes, which can hinder adaptive responses to the social environment. Additionally, it has been linked with affective dysregulation and neuroticism, complicating its role in both schizotypal and SSD phenotypes13,15,17.

All these dimensions must be interpreted as interrelated rather than independent. For example, disorganised traits may amplify the social difficulties seen in negative schizotypy, while also contributing to increased paranoid ideation in positive schizotypy. This interconnectedness underscores the need to study schizotypy as an integrated system of traits rather than as isolated dimensions, as these traits collectively shape the clinical expression of schizotypy and its evolution into more severe disorders15.

Measuring schizotypy

Studying schizotypy requires delving into the complex interplay between personality and psychopathology, which, in turn, leads us to question how frameworks for diagnosing psychopathologies were designed. The current diagnostic systems of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5 (DSM-5)18 and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases-11 (ICD-11)19 have some limitations. Due to their categorical diagnostic approach, they lack the nuance needed to identify disorders along a continuum from healthy to pathological, rather than as all-or-nothing conditions20,21,22,23,24. This approach leaves the definition of some disorders outdated and can often lead to misdiagnoses. Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia can, for example, occur for schizotypy itself, schizoaffective disorder or major depressive disorder with psychotic features25.

To measure schizotypy as a stable personality structure, psychometric instruments, especially self-report questionnaires, are commonly used due to their cost-effective and non-invasive nature26,27. However, the validity of these assessments depends on the theoretical framework of the instrument, which may focus on either clinical or broader dimensional aspects14,15,28.

Two scales, the multidimensional schizotypy scale (MSS) and the Oxford-Liverpool inventory for feelings and experiences (O-LIFE), provide comprehensive coverage of the three symptomatological dimensions that schizotypy has in common with schizophrenia (positive, negative and disorganised). They both demonstrate robust psychometric properties29,30,31,32,33.

The MSS, aligned with the taxonomic view of schizotypy, explores experiences akin to symptoms of SSD but in milder form34. In contrast, the O-LIFE adopts a personality-oriented approach, in which psychotic features are not viewed differently from other traits that vary in the population, such as anxiety or rumination, and that can potentially lead to either healthy or unhealthy outcomes. The O-LIFE’s theoretical approach extends the concept of schizotypy beyond a reductionist view of it as merely a clinical entity or spectrum, instead focusing more on how the traits are more or less adaptive to the environment35.

The taxonomic framework underpinning the development of the DSM has shaped the design and calibration of most psychological scales, which are based on the assumption that unobservable (latent) factors influence observable variables through linear relationships. This framework aligns well with techniques like exploratory factor analysis (EFA), which is extensively used in psychological research due to its suitability for theoretical models of this nature.

When considering a healthy-pathological trait continuum, such as with personality traits, however, strong direct interdependencies between symptoms or behaviours are common, and boundaries are often less clear-cut. This dynamic quality is not captured by techniques like EFA, limiting their ability to represent how traits may transform or influence each other along the continuum. Therefore, to study the construct of schizotypy there is a need to use techniques that can go beyond this limitation36,37.

Network analysis in schizotypy

In complex systems science, the network theory of psychopathology supports current views on schizotypy as a multidimensional construct and a latent risk for SSD38,39. Exploratory graph analysis (EGA) offers a complementary network-based approach to uncovering dimensions within psychometric instruments40,41,42. It can be used to identify clusters of directly related variables without relying on a rigid factor structure or researcher-imposed bias. Unlike EFA, which assumes that the covariance among items arises from latent variables, EGA does not rely on such assumptions. Instead, it focuses on modelling direct relationships between items via partial correlations, providing unique insights into the data structure within and between clusters. This approach is particularly advantageous for exploring multidimensional constructs like schizotypy and SSD, where symptoms interact in complex ways and may not be fully explained by a latent factor.

EGA employs a Gaussian graphical model, computed using the graphical least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (glasso)43,44,45. To capture the intricate interdependencies among variables, clusters are identified using community detection algorithms, such as Walktrap or Louvain, which rely on connection measurements within the network rather than rotations or linear extraction methods typical of EFA. These algorithms, guided by objective statistical criteria, such as modularity maximisation, have demonstrated robust performance in psychological datasets, especially when item clusters are well-defined. Both methods ultimately identify latent variables (clusters in networks correspond to factors in EFA), but the process by which they do so differs significantly. A detailed description of EGA’s methodological approach is provided elsewhere42.

A further strength of EGA is the intuitive, graphical representation of item relationships provided; it offers a visual network of connections that facilitates interpretation and complements the abstract factor-loading tables produced by EFA. This allows for a robust and clear examination of the complex interdependencies among not only the three main factors but also all the item variables. Numerous studies, both with real and simulated data, have shown that EGA performs as well as, or better than, traditional methods like EFA or principal component analysis in accurately identifying questionnaire structures. This highlights its potential for providing deeper insights into the clinical constructs these instruments aim to measure42,46,47,48,49.

The only research to date that has applied EGA to a schizotypy questionnaire is that of Christensen et al. 31. They investigated the structure of the MSS and MSS-B (short form) in an English-speaking healthy population using the EBICglasso method (i.e. using a penalised maximum likelihood solution based on the extended Bayesian information criterion) and the Walktrap algorithm. While the three positive-negative-disorganised domains were found in the short version, the EGA of the full version showed the presence of a division of the ‘negative’ domain into two, which they called ‘social anhedonia’ and ‘affective anhedonia’. Regarding the O-LIFE, to date no one has applied EGA to study its factorial structure, although the study by Polner et al., 201933 used an IsingFit model40 and a fast greedy algorithm to explore the structure of schizotypy in the general population using the German short version of the questionnaire (i.e. sO-LIFE). They were able to identify four factors that overlapped by 93% with the original ones and showed that the “impulsive nonconformity” factor had modest internal consistency reliability.

Both these studies explored schizotypy structure; one in a healthy population and the other in a general population. However, differences between the two studies in the sample composition and the choice of network models, clustering algorithms, and R packages, cause a lack of methodological comparability. This limitation reduces the utility of their results, leading clinicians to base their choice of test on theoretical rather than psychometric aspects.

Present study

Building on insights from previous studies and the authors’ recommendations, the present study has a two-fold aim. The first is to address the methodological inconsistencies that arise from the use of psychometric validation techniques based on categorical models of diseases (DSM/ICD) when studying multidimensional constructs. These inconsistencies influence the design of psychological tests and the selection of statistical methods, highlighting the need for approaches that better capture schizotypy as a continuum rather than a binary entity. To achieve this, this study employs EGA, a method aligned with models that conceptualise schizotypy as a complex system of interrelated personality traits. By doing so, it aims to uncover the intricate structure and relationships among these traits, which range from healthy to pathological.

The second aim is to address the gap in research on how cultural differences influence the expression of schizotypal traits; studies on the cross-cultural validity, reliability, and structural equivalence of psychological tests and questionnaires are still limited. By examining the factorial structures of both the MSS and O-LIFE within a single sample of native German speakers, this study is the first to allow a direct comparison of how each scale conceptualises schizotypy in the same cultural context. This dual analysis contributes to both theoretical and methodological precision, enhancing our understanding of the schizotypy construct and reinforcing the clinical applicability of schizotypy assessments across diverse cultural populations.

Results

Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic characteristics of the sample of 1059 participants.

To evaluate the quality of responses to the dichotomous questionnaires, we employed multiple reliability and consistency checks. Both questionnaires demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.9 and the Kuder–Richardson 20 (KR-20) index also returning a value of 0.9. Consistency between reverse-coded items confirmed the reliability of responses, even among the 100 participants (10% of the sample) who answered all items on the MSS as false. Additionally, chi-squared tests indicated that the response distributions significantly deviated from random patterns (p < 0.001), further supporting data validity. Jennrich’s tests were not significant so no difference could be assumed between the correlation matrices using full information maximum likelihood (Fiml) correlations, Spearman’s correlations and phi coefficients (mean square contingency). We opted to use Spearman correlations for conducting the EGA in both questionnaires.

MSS model

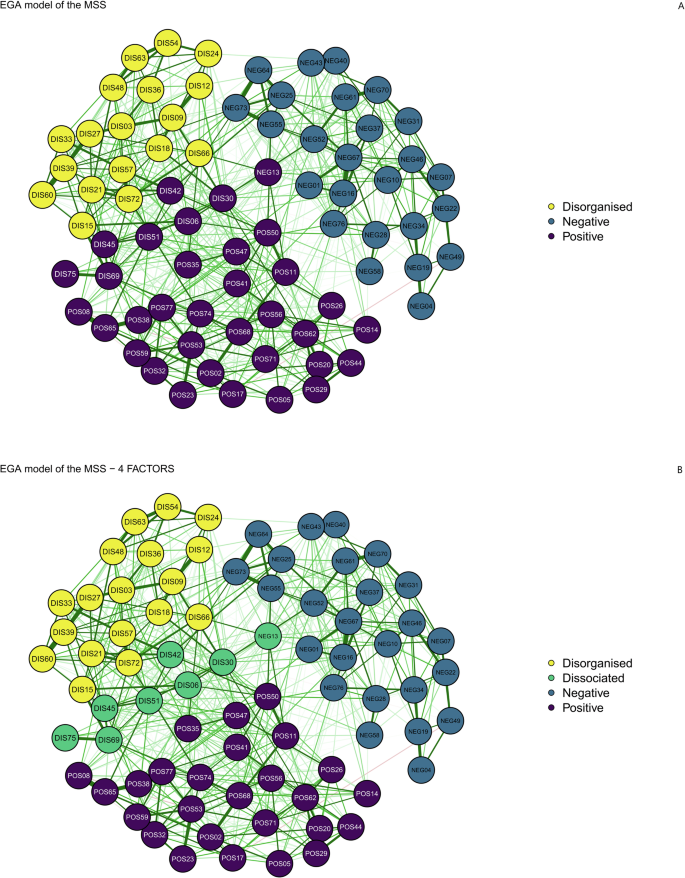

EGA analyses for the MSS revealed a three-dimensional structure in our sample, reflecting the division of positive, negative and disorganised symptoms. The positive and disorganised dimensions have a higher density of connections between them than the negative domain. Of all the items, eight were shifted (i.e., misfit) in the positive domain by the EGA: one of these was part of the negative factor, and seven were part of the disorganised factor. The specific items are listed below:

-

NEG01: I have always preferred to be disconnected from the world

-

DIS06: When people ask me a question, I often do not understand what they are asking

-

DIS30: I often find that when I talk to people, I do not make any sense to them

-

DIS42: I often feel so disconnected from the world that I am not able to do things

-

DIS45: I am very often confused about what is going on around me

-

DIS51: People find my conversations to be confusing or hard to follow

-

DIS69: I have trouble following conversations with others

-

DIS75: It is usually easy for me to follow conversations

These items were analysed in both the English and German versions by two psychologists, two psychotherapists, and two psychiatrists at the University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich to assess whether they have aspects in common which led the algorithm to position them in a domain they originally did not belong to. This post-hoc thematic analysis revealed that all these items share a common theme related to disconnection from the world, being confused or being confusing. In Fig. 1 part B, these items are visually separated from the others, forming a distinct fourth domain we named ‘dissociated’.

A MSS network representing the three factors identified by the EGA. B MSS network with the green group/factor “dissociated” highlighted. The green edges represent positive Spearman correlations.

Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) analysis was conducted to evaluate the fit of three potential models: the original scale model, the three-factor model identified by the EGA, and a third model that includes the separate factor ‘dissociated’ encompassing the items classified as misfits. The indices of interest are shown in Table 2.

The Satorra–Bentler tests performed to compare these three models were not significant, indicating that there is no significant difference between them. The four-dimensional EGA model shows better fitting values than the other two, as can be seen in Table 2. Furthermore, the ‘negative’ factor exhibits high internal consistency (alpha = 0.85) and strong general factor saturation (omega total = 0.87). Similarly, the “positive” factor shows high reliability (alpha = 0.85) and strong general factor saturation (omega total = 0.87).

The ‘disorganised’ factor demonstrates excellent reliability (alpha = 0.92) and an optimal general factor saturation (omega total = 0.93). Finally, the new ‘dissociated’ factor exhibits good reliability (alpha = 0.74). The general factor saturation (omega total = 0.81) is lower than that of the others but still considered good as a substantial portion of the variance is due to common factors, suggesting good internal consistency.

O-LIFE model

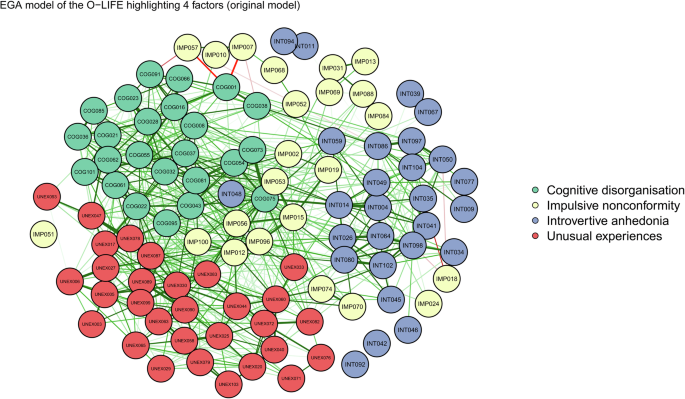

The EGA analysis for the O-LIFE questionnaire showed a 13-factor structure. Its representation, grouping the four subscales of the test by colour (Fig. 2), revealed multiple nodes that were either uncorrelated or connected two by two. Moreover, the factor ‘impulsive nonconformity’ is the one that least maintains a unitary structure, with its nodes spreading out among the others.

O-LIFE network identified by the EGA separating the nodes with the four subscales proposed by the model of Mason and Claridge (2006).

To control for possible confounding effects and to explore the number of factors, an EFA was conducted. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test, although giving an overall measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) of 0.9, revealed that seven items had values below 0.7 and a further ten between 0.7 and 0.8. The parallel analysis then performed with tetrachoric correlations identified four main factors, but the individual loadings showed several items having high positive and/or negative correlations with more than one factor at the same time.

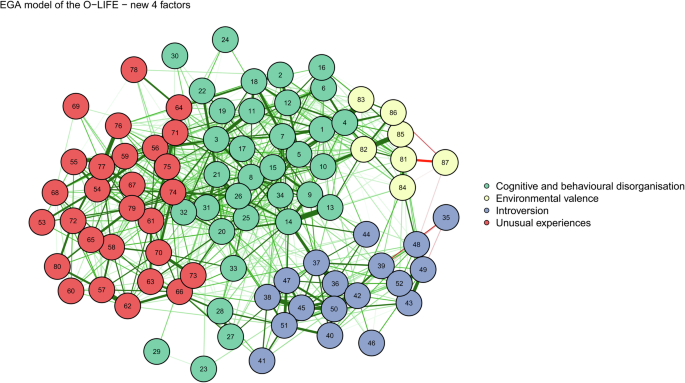

Items with a measure of sampling adequacy of less than 0.7 were first removed from the dataset, resulting in a reduction in the number of factors from 13 to 9. Those with a value between 0.7 and 0.8, were then removed, resulting in a total of 4 factors. The final network can be observed in Fig. 3.

The green edges represent positive Spearman correlations, red edges are negative correlations.

CFA was performed for: the original model with all 104 items, the 104-item model obtained with EFA (EFA model) and the EGA four-dimensional model with 87 items (i.e. final model; after removing those with low MSA). The results of the fitting of each model are reported in Table 3.

The EGA four-dimensional model was found to have the best indices. Furthermore, the Satorra–Bentler test was significant when comparing the final model with the other two in both cases:

-

Final model vs. original: chi2 difference = 2637; df difference: 1496; p = 2.2 × 10−16

-

Final model vs. EFA model: chi2 difference = 2454; df difference: 1598; p = 2.2 × 10−16

After analysing the new item groups, two remained stable and similar to the original model (‘introvertive anhedonia’, now ‘introversion’ and ‘unusual experiences’), while the other two were renamed as ‘cognitive and behavioural disorganisation’ and ‘environmental valence’.

The reliability analysis for the four variables indicates robust internal consistency and well-defined factor structures. The “cognitive and behavioural disorganisation” domain shows high reliability with an alpha of 0.88 and an omega total of 0.89, alongside significant contributions from both general and group factors. Introversion is also reliable, evidenced by an alpha of 0.82 and an omega total of 0.83, with the general factor explaining a substantial portion of the variance. ‘Unusual experiences’ has strong reliability, with an alpha of 0.86 and an omega total of 0.87, indicating that both the general factor and group factors are important. ‘Environmental valence’, while slightly lower in reliability, still demonstrates good consistency with an alpha of 0.70 and an omega total of 0.75, dominated by the general factor.

The model fits, as indicated by RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) values below 0.05 for all variables, suggesting that the models are appropriate and explain a considerable amount of the variance. Correlations of scores with factors and multiple R2 values are high for the general factor, confirming the adequacy of the factor score estimates. Despite some negative values in the minimum correlations for group factors, the overall reliability and factor structures are robust, ensuring the scales are reliable and effectively capture the intended constructs.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the influence of cultural context on the expression and measurement of schizotypal traits, providing insights into how the MSS and O-LIFE conceptualise schizotypy within a shared cultural framework. To achieve this, schizotypy was studied using EGA to avoid treating it solely as a diagnostic category with predefined latent factors. The psychometric properties of both the MSS and the O-LIFE were examined in a single German-speaking sample. This not only provides information about the cross-cultural validity and reliability of these, initially English language questionnaires, but also enables a direct comparison of how each scale conceptualises schizotypy in the same cultural context.

EGA analyses of the MSS revealed a three-dimensional structure, and an additional fourth distinct ‘dissociated’ factor related to experiences of disconnection from the world and difficulty in understanding or being understood by others. For the O-LIFE, EGA confirmed a four-factor model after excluding items with low MSA, resulting in a revised item organisation compared to the original model. Two factors were renamed as ‘cognitive and behavioural disorganisation’ and ‘environmental valence’. For both tests, CFA confirmed that the new models had the best fit, with robust reliability for all factors, demonstrating the scales’ effectiveness in capturing the intended constructs.

Our results mark a significant advancement in the understanding and assessment of schizotypy by uncovering new factor structures that enrich previous conceptions of schizotypal traits. They provide evidence that schizotypy is not a simplistic model, but rather encloses complex, interconnected domains, including dissociation and environmental factors, which were not previously independently explored. By proposing new domains, this research highlights the importance of studying psychological constructs across different populations to improve their operationalisation, emphasising the need for integrated assessment tools that can support more targeted clinical interventions.

Unveiling the ‘dissociated’ domain in the MSS structure

The newly identified domain ‘dissociated’ serves as a broader conceptual framework encompassing two distinct but interconnected themes: disconnection from the world and being confused by or confusing to others. Disconnection from the world refers to experiences of detachment or isolation from one’s surroundings, reflecting difficulties in perceiving or engaging with reality. Being confused or confusing, on the other hand, captures interpersonal and cognitive challenges, such as being misunderstood or struggling to understand others, often linked to social and cognitive disorganisation. Both themes align under the overarching concept of dissociation, which we conceptualise as a disruption in the integration of perception, cognition, and social connection. These experiences are considered early indicators of schizotypal personality traits and may precede the onset of SSD50,51. By framing these phenomena within the domain of dissociation, we emphasise their shared foundation in disrupted psychological integration while acknowledging their distinct phenomenological expressions52.

The clinical significance of identifying dissociation as a distinct symptom domain lies in its potential for earlier and more precise intervention in schizotypy and schizophrenia treatment. Recognising dissociative experiences as early indicators may help clinicians to develop more targeted treatment strategies, potentially improving patient outcomes by intervening at a stage where these early warning signs can be mitigated. For example, interventions targeting dissociative symptoms—such as grounding techniques, therapies for emotional regulation, or social integration strategies—could be tailored to individuals whose schizotypy profiles prominently feature dissociation53,54.

Interestingly, these dissociative items were found to mediate between positive and disorganised symptoms, highlighting the interconnectedness of schizotypal traits55. Treatments that specifically target the dissociative domain could thus alleviate both positive and disorganised symptoms simultaneously.

The fact that we did not find, as Christensen et al.31 did, a subdivision within the negative domain of the MSS into affective and social anhedonia and the suggestion of a potential four-dimensional structure in the MSS, with the identification of the ‘dissociated’ factor, invites further exploration into the dimensionality of schizotypy. By isolating this factor, we gain a conceptually distinct domain that may reflect a unique psychological or neurobiological process. If dissociative experiences can indeed be separated as a distinct dimension, this opens the door for further refinement of the MSS, including the development of additional items specifically targeting this domain. This could improve the scale’s sensitivity to dissociative phenomena.

Understanding the role of the perceived environment from the O-LIFE structure

The O-LIFE required adjustments to its factor structure due to the instability of certain domains, specifically the ‘impulsive nonconformity’ factor, which had already been observed in the standardisation of the German version29. Two new domains were identified: ‘cognitive and behavioural disorganisation’ and ‘environmental valence’. The merging of items from ‘impulsive nonconformity’ and ‘cognitive disorganisation’ into a single domain suggests that these traits may not be distinct but rather exist in a symbiotic relationship, where impulsivity and disorganisation are linked. The revisions to the O-LIFE, particularly the identification of the ‘environmental valence’ domain, could have significant clinical implications because it highlights the role of the social environment in schizotypy, particularly the fear of judgment or harm by others. These experiences are shaped by the dynamic interaction between internal and external factors, where social environments amplify or mitigate the expression of schizotypal characteristics.

The ‘environmental valence’ domain reflects the perceived social judgement individuals experience in interactions. This highlights a dynamic relationship: internal sensitivities (e.g., paranoia, social withdrawal) can amplify perceptions of negative social evaluation, while external social pressures may exacerbate these internal traits. Recognising this interplay underscores the need for therapeutic approaches that do not solely target individual symptoms but also address how the individual perceives and interacts with their broader social context. Future treatments could benefit from incorporating multifaceted interventions, combining therapies to improve social cognition, reduce self-consciousness, and bolster coping mechanisms for navigating external stressors. For example, interventions might include cognitive-behavioural techniques focused on reframing perceived judgement or harm and social-skills training to reduce withdrawal and increase confidence in social interactions.

Limitations

This study suffers from some limitations that should be mentioned. First, all the models analysed in this article presented out-of-range standardised root mean residual (SRMR), while all the other measures are considered good or optimal. An SRMR out-of-range (usually >0.08) suggests that the model may not fit the data perfectly, indicating potential issues in correctly representing the latent structure. Since the overall quality of a model should not be based on a single fitting index, the models were presented as valid while considering the presence of some residuals contributing to these SRMR values. Secondly, the two sexes were not equally represented in our sample, as males accounted for 28.35% of participants. Finally, although techniques were applied to detect response patterns, and to check the completion times of the questionnaires it always remains uncertain whether participants respond truthfully to all items.

Conclusions

This study identified new factorial structures in both the MSS and O-LIFE. The ‘dissociated’ domain in the MSS highlights the potential significance of dissociative experiences in the early stages of schizotypal traits, suggesting an avenue for future research into targeted interventions addressing these experiences. Similarly, the reorganisation of the O-LIFE structure highlights the importance of the social environment, with the addition of the ‘environmental valence’ domain, suggesting that external factors should be considered in the treatment of schizotypy. These findings underscore the multidimensional nature of schizotypy and the value of integrated assessment tools operationalised in multiple cultures and languages for more personalised clinical care.

Future research should further investigate the nature of schizotypy by developing refined diagnostic tools that use multidimensional and network-based methods. Studies should also examine both internal and external factors across diverse populations to understand how these shape personality traits.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants were recruited via an online survey aimed at identifying potential candidates for a comprehensive study at the University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich (i.e. the VELAS study: https://homanlab.github.io/velas/). The survey was distributed using various means (institutional email, tweets by the research team, direct contact with educational institutions, marketplaces and commercial walls), with the aim of attracting individuals with diverse educational and social backgrounds.

Prospective participants were provided with a description of the study and the protocol. Consent to data processing and the publication of study results was requested prior to the completion of the test battery. Only once participants had provided consent and confirmed with ticks that they understood the study and its associated data collection and analyses, were they given access to questions about demographics, MRI safety and the German versions of the MSS and O-LIFE.

Due to the main study’s specific research requirements, there were several eligibility criteria. Participants were required to be:

-

healthy (i.e. without any diagnosed psychiatric or neurological conditions),

-

aged between 18 and 40 years,

-

right-handed,

-

proficient in German.

Participants who were selected and took part in the main study received compensation of 150 Swiss francs, while those not selected after completing the survey received no compensation. A total of 1059 participants completed the entire study between April 2021 and March 2024. Since the demographic and MSS and O-LIFE items were programmed as forced-choice questions, no missing values were present in the dataset.

Questionnaires

German versions of the MSS and O-LIFE were used. These had been translated by bilingual researchers from the International Consortium of Schizotypy Research (ICSR) and have been utilised in other studies29,56.

The MSS consists of 77 yes-or-no items, divided into subscales: 26 items in both the ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ subscales, and 25 items in the ‘disorganised’ subscale. Previous studies with larger samples have shown the internal consistency of these subscales to be good to excellent, with binary adjusted alpha coefficients ranging from 0.87 to 0.95 in English-speaking samples, and from 0.78 to 0.89 in German-speaking samples14,34,56.

The O-LIFE comprises 104 yes-or-no items, with 30 items in the ‘unusual experiences’ (UnEx) subscale, 27 in the ‘introvertive anhedonia’ (IntA) subscale, 24 in the ‘cognitive dysregulation’ (CogDis) subscale, and 23 in the ‘impulsive nonconformity’ (ImpNon) subscale. Alpha coefficients for these subscales were found to be between 0.77 and 0.89 in English-speaking populations in studies by Mason and Claridge35, and between 0.68 and 0.88 in a German-speaking sample in research by Grant et al.29. Notably, the latter study showed that the ImpNon subscale had the lowest alpha coefficient, which was psychometrically unacceptable, while the other three subscales (UnEx, IntA, CogDis) had coefficients above 0.8, indicating good to excellent internal consistency.

Statistical analysis

The demographic data were analysed quantitatively by extrapolating averages, standard deviations and percentages. To ensure the validity and reliability of participant responses, several techniques were employed to identify the potential random or pattern-specific response behaviours: (i) Cronbach’s alpha was assessed for each questionnaire to evaluate internal consistency and ensure that the items reliably measure the intended constructs in our study population; (ii) response patterns such as “ALL TRUE”, ‘ALL FALSE’, ‘TRUE-FALSE’ alternating were systematically searched for, as they may indicate careless or invalid responding; and (iii) two additional tests were applied for finding subtler patterns. These were the Kuder–Richardson 2057, which assesses internal consistency specifically for dichotomous items, and the chi-squared test which evaluates response distributions to detect irregularities or systematic biases. Finally, given that this study involved a healthy population, we checked for consistency between responses to reversed and unreversed items, as discrepancies could indicate response biases or lack of attention.

To determine the most suitable correlation method for constructing the matrices used in the EGA, we conducted Jenrich’s test58. This allowed us to compare Fiml correlations, as employed in Christensen et al.31, with Spearman’s correlations and phi coefficients, which are specifically used for categorical and dichotomous variables31.

We utilised the ega package42 in R to perform the EGA, employing first the qgraph to apply the glasso algorithm59 and then igraph60 to compute the Walktrap clustering methods61. The glasso method was estimated using a penalised maximum likelihood solution based on the extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC)45,62. The Walktrap community detection algorithm was then used to identify network dimensions by performing ‘random walks’ from one node to another, forming communities based on densely connected edges61. The representation of the networks was done using the ‘qgraph’ package.

If the number of factors found was excessively large or if issues emerged in the correlations of single items from the representation, an EFA was conducted. First, a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test63 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity64 were performed. Then, if the items’ MSA values were inadequate, the EGA was conducted again without those items.

The correlation matrices of the individual factors of each model were estimated using the WLSMV (diagonally weighted least squares estimator)65. Each model was fitted using the ‘lavaan’ package66 in R. The fitting of the models obtained were compared to each other using the Satorra–Bentler chi-squared test67 and qualitatively using the comparative fit index (CFI), SRMR, RMSEA and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). Based on the results, the best model was chosen, and the reliability measures, such as McDonalds’ omega68 and Cronbach’s alpha69 of each factor were calculated. While these techniques are traditionally associated with EFA, they remain relevant in the context of EGA. Given that confirmatory methods and reliability assessments specific to EGA are not yet widely available, integrating CFA, alpha, and omega offers a way to rigorously evaluate the EGA-derived models and compare them with EFA-derived models.

For each final network model of both questionnaires, centrality analyses including ‘Strength’, ‘Betweenness’ and ‘Closeness’ were performed. Given the criticism of Bringmann et al.70, on the use of these analyses due to their ‘instability’ and as none of the previous studies mentioned in the introduction used them, we opted not to consider them in the description of the resulting models.

Responses