Shared genetic architecture and causal relationship between frailty and schizophrenia

Introduction

Frailty is defined as a clinical state of deficit accumulation in which individuals are more vulnerable to developing adverse health outcomes when exposed to endogenous or exogenous stressors1. According to current knowledge, frailty is associated with an elevated risk of developing various physical and mental diseases, which include but are not limited to coronary artery disease2, type 2 diabetes2, stroke3, osteoarthritis4, anxiety5, bipolar disorder6, and depression7. These findings indicate that understanding the potential correlation between frailty and frailty-related outcomes would be important and beneficial for disease prevention and control.

Schizophrenia is a serious mental disorder characterized by positive, negative, or cognitive symptoms, which affects up to 1% of the population8 and could significantly reduce patients’ life expectancy9. Epidemiology studies have identified a series of factors related to schizophrenia risks, such as physical activity10, cannabis use11, circulating selenium level12, and C-reactive protein13, which greatly contribute to implementing effective primary prevention measures.

Nevertheless, regarding the relationship between frailty and schizophrenia, research is relatively limited and mainly focuses on the adverse effects of frailty in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. For instance, the previous retrospective cohort study analyzed the frailty status of 78 adults with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and found that frailty was at a very high prevalence and positively correlated to disease severity14. In addition, another two observational studies discovered that schizophrenia and fragile individuals were more likely to reduce employment duration and income15, and had a lower life quality16. However, whether frailty plays a role in schizophrenia pathology and whether people are more likely to be fragile after developing schizophrenia remain unclear.

Based on the aforementioned background, we intend to investigate the relationship between frailty and schizophrenia from the genetic perspective by utilizing the data from the genome-wide association studies (GWAS)17,18.

Materials and methods

Data sources

Data related to frailty was obtained from the recent GWAS of fried frailty scores (FFS) in 386,565 European descent participants enrolled in the UK Biobank, whose average age was 57 years old and females occupied a percentage of 54%17. FFS consists of five criteria including weight loss, exhaustion, physical activity, walking speed, and grip strength, and ranges from 0 to 5 scores according to the number of criteria met19. Although FFS was commonly modeled as a binary variable (scores ≥3 being frailty), Ye et al. analyzed it as an ordinal variable in the original GWAS in order to reduce information loss and enhance statistical power17.

Schizophrenia associated data was retrieved from the recent multi-ancestry GWAS of up to 76,755 individuals with schizophrenia and 243,649 controls18, which include a total of 67,390 cases and 94,015 controls from a core Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) dataset of 90 cohorts of European and East Asian ancestry, 7386 cases and 7008 controls from 9 African American and Latino ancestry cohorts, 1979 cases and 142,626 controls from deCODE. In our study, we extracted the summary-level genetic variants from a sub-sample of 52,017 individuals with schizophrenia and 75,889 controls with European ancestry.

Statistical analyses

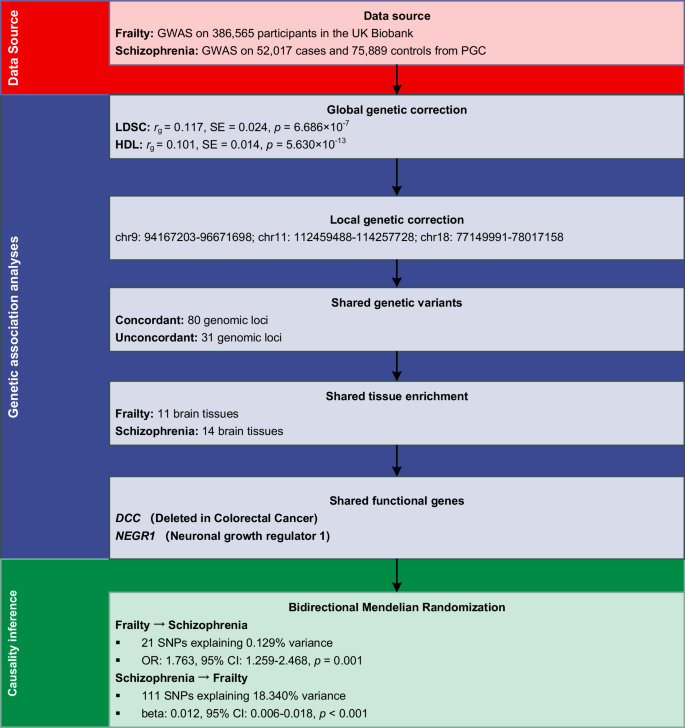

An overview of statistical analysis procedures is presented in Fig. 1. We first examined the underlying genetic association between frailty and schizophrenia from five perspectives: global genetic correlation, local genetic correlation, identification of shared genetic loci, shared tissue enrichments, and shared functional genes. Then, the Mendelian Randomization (MR) design was utilized to estimate their bidirectional causality.

An overview of study design.

Global genetic correlation

The linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC), which could be applied to evaluate the cross traits genetic correlation from GWAS summary statistics20, was performed to assess the global genetic correlation (rg) between frailty and schizophrenia based on the GWAS summary statistics. The European samples from the 1000 Genomes Project were used as reference panel21.

Additionally, we utilized the high-definition likelihood (HDL) method to estimate the global genetic correlation between frailty and schizophrenia, which can reduce the variance of genetic correlation estimates and improve estimation accuracy than LDSC22. The HDL was performed with 1,029,876 QCed UK Biobank imputed HapMap3 SNPs as the reference panel22.

Local genetic correlation

In addition to global correlation analysis, we also attempted to explore whether frailty and schizophrenia were locally correlated at a special region across the entire genome. We utilized the ρ-HESS (Heritability Estimation from Summary Statistics)23,24, which was software for estimating and visualizing local SNP-heritability and genetic correlation based on GWAS summary data. ρ-HESS partitioning the entire genome into 1703 LD independent regions of 1.6 MB window size on average based on the European population LD reference panel. Then, the local genetic correlation between frailty and schizophrenia was quantified in each region, and the Bonferroni corrected p value of p < 0.05/1703 was set as the significance threshold.

Identification of shared genomic loci

We used the pleiotropy-informed false discovery rate (pleioFDR) software25 to determine if any shared genetic variants contribute to both frailty and schizophrenia. This software helps to increase the discovery of genetic loci in low-powered GWAS by leveraging pleiotropic enrichment with a larger GWAS on a related phenotype and identifying genetic loci jointly associated with the two phenotypes.

We first employed the conditional false discovery rate (condFDR) as a means to improve the identification of genetic variations associated with frailty and schizophrenia. The condFDR methodology relies on an empirical Bayesian statistical framework and leverages summary statistics from both a primary (schizophrenia) and a conditional (frailty) trait. This enables the estimation of the posterior probability that a SNP is not related to the primary trait. By reranking the test statistics of schizophrenia conditional on the strength of the correlation with frailty, this technique enhances the detection of genetic variants linked to schizophrenia. Similarly, the reverse condFDR statistics that frailty conditional on schizophrenia were calculated when the primary and conditional traits were inverted. The significance level for the condFDR was set as condFDR <0.0125.

Next, we calculated conjunctional FDR (conjFDR) statistics to identify any genetic loci that might be shared by frailty and schizophrenia, which is an extension of the condFDR and it represents the maximum of the two condFDR statistics for a specific SNP. This value estimates the posterior probability that an SNP is null for either trait or both, given that the p values for both phenotypes are as small as or smaller than the p values for each trait individually. The significance level for the condFDR was set as conjFDR <0.0525.

Tissue enrichment

To explore whether the GWAS SNP heritability related to frailty and schizophrenia were enriched in some shared tissues, we utilized the MAGMA (Multi-marker Analysis of GenoMic Annotation)26 that was implemented in FUMA (Functional Mapping and Annotation)27 to perform the tissue enrichment analyses based on the expression profiles from GTEx v8 tissues28. The major parameters we used in FUMA including the maximum p value of lead SNPs were set as p < 5 × 10−8, and the upstream and downstream windows size of genes to assign SNPs were limited to 35 and 10 kb29, respectively. The other parameters and settings were used default. Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple testing and a p value less than 0.05/54 was set as the significance threshold.

Summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) analysis

Potential risk genes for frailty were identified using SMR tool, which integrates GWAS summary statistics for each phenotype with human brain expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data30. The brain cis-eQTL data, which included 2865 brain cortex transcriptomic data from 7 cohorts31, were retrieved from the SMR website30. The heterogeneity in dependent instrument (HEIDI)-outlier filtering method was preliminarily performed to distinguish causality or pleiotropy from linkage, and those with p values for HEIDI < 0.05 and NSNPs_HEIDI < 10 were considered likely caused by pleiotropy and removed. The SMR analyses were performed using the SMR software (version 1.3.1) with the default parameters, and a false discovery rate of 0.05 was considered as the significant threshold.

The risk genes for schizophrenia were obtained from the previous work by Trubetskoy et al.18, who performed SMR combined with other approaches (Table S12 in their paper). We used this prioritized gene list for schizophrenia to compare with the genes we identified for frailty in our study, aiming to find common genes between frailty and schizophrenia.

Mendelian randomization

Using the genetic variants as the instruments, MR is a useful method to obtain plausible causal inference and the instruments should satisfy the relevance, independence, and exclusion restriction assumptions to make the causal estimates valid32. The diagram of MR design in this study is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. We performed MR within two directions: (1) genetic variants related to frailty as exposure to assess whether fragile people are more likely to develop schizophrenia and, (2) genetic variants associated with frailty as outcome to evaluate whether the schizophrenia patients are more fragile.

Instruments robustly related to exposure were initially screened at genome-wide significance (p < 5 × 10−8). Then, the identified variants were clumped for linkage disequilibrium (LD) using the European samples from the 1000 Genomes Project21 as the reference panel, with the cutoff of clumping R2 set as 0.001 in the window of 10,000 KB. To avoid the bias from weak instruments, the F statistic for each was calculated and only those with F statistics greater than 10 were reserved33. In addition, the modified Cochran’s Q test was performed to identify outlier pleiotropic SNP as the Q statistic much larger than NSNP-1 suggests the violation of the independence assumption or exclusion restriction34. After harmonization of exposure and outcome data with no palindromic SNPs, the remaining genetic variants were used to perform MR analysis.

The inverse variance weighted (IVW) method was utilized as the primary method for causal inference, and the IVW method under fixed-effect was adopted when no obvious heterogeneity was found, otherwise, under the random-effect. Several other methods including MR-Egger, weighted-median, MR-PRESSO (Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier), and MR-cML (Constrained maximum likelihood) were supplemented to assess the stability of the results. Two additional sensitivity analyses were performed including the MR-Egger regression intercept to check the horizontal pleiotropy and the leave-one-out analysis to assess whether the causality was driven by a single variant.

The effect size was reported in beta values with the 95% confidence interval (CI) when the outcome was frailty and converted to odds ratio (OR) when the outcome was schizophrenia. Statistical analyses were performed in R software (version 4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with TwoSampleMR (version 0.5.7), MendelianRandomization (version 0.8.0), and RadialMR (version 1.1) packages.

Results

Genetic association between frailty and schizophrenia

Global genetic correlation

The result of LDSC presented that genetic variants related to frailty and schizophrenia were positively correlated (rg = 0.117, SE = 0.024, p = 6.686 × 10−7), and a similar positive correlation between frailty and schizophrenia (rg = 0.101, SE = 0.014, p = 5.63 × 10−13) was obtained by the HDL method.

Local genetic correlation

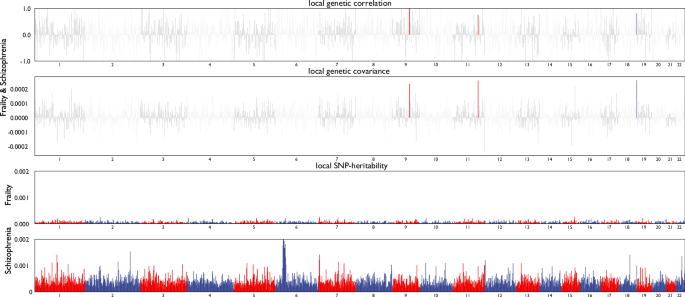

The results of ρ-HESS to investigate the local genetic correlation across 1703 genomic regions between frailty and schizophrenia were presented in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1. For each region, ρ-HESS calculates local SNP heritability, genetic covariance, and standard error. Frailty and schizophrenia were initially found to be locally correlated in a total of 202 genomic regions at p < 0.05. However, after correcting for multiple tests, only three regions remained significant. The most significant region is located on chromosome 9 (chr9: 94167203-96671698; p = 2.21 × 10−6). The other two significant regions are on chromosome 11 (chr11: 112459488-114257728; p = 1.01 × 10−5) and chromosome 18 (chr18: 77149991-78017158; p = 9.57 × 10−6).

Local genetic correlation and genetic covariance between frailty and schizophrenia, and local SNP heritability estimation for frailty and schizophrenia respectively.

Leveraging condFDR and conjFDR to identify shared genomic loci

We first checked the quantile-quantile (Q–Q) plots of frailty when conditioned on the p value of schizophrenia and vice versa. We observed sharp leftward deflection from the theoretical black dashed line (no association) to an increasing association with schizophrenia when condition on frailty (Supplementary Fig. S2A) and vice versa (Supplementary Fig. S2B). At condFDR <0.01, we identified 289 loci that showed significant association with schizophrenia when conditional on frailty, and reversely 79 loci that showed significant association with frailty when conditional on schizophrenia (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

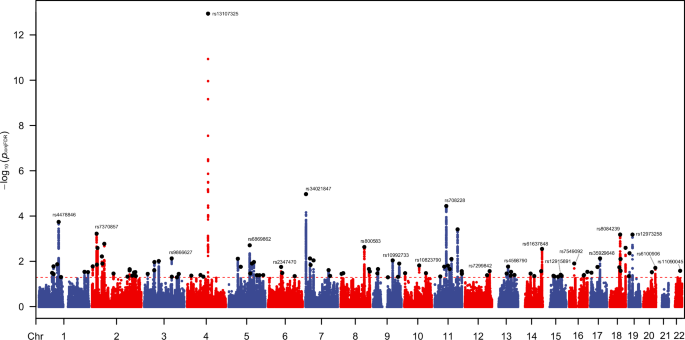

To identify the shared genomic association between frailty and schizophrenia, we calculated the conjFDR for these two phenotypes, and the results are presented in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S4. We identified 111 genomic loci in total which are jointly associated with both frailty and schizophrenia, and the most significant locus is located in chromosome 4 (Lead SNP: rs13107325, p = 2.90 × 10−21). When assessing their effects on each trait, we discovered that there were 80 SNPs yielded consistent (both positive or negative) effects on frailty and schizophrenia, while the rest 31 SNPs did not.

The red dashed line represents the threshold of p value for conjFDR <0.05; The black points are the lead SNPs.

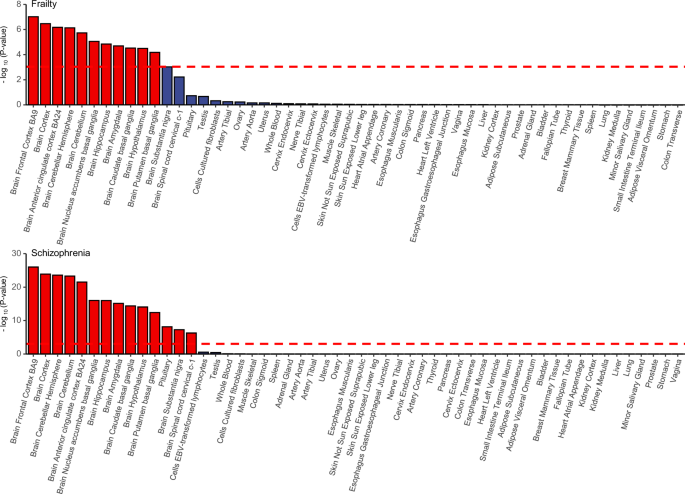

Tissue enrichment

MAGMA analysis facilitates the identification of tissue-specific enrichment of SNP heritability for both frailty and schizophrenia. If a close genetic relationship exists between frailty and schizophrenia, their GWAS SNP heritability would be expected to show enrichment in shared tissues; otherwise, it would not. Given the significant correlations identified in previous analyses, we hypothesized that the SNP heritability for frailty and schizophrenia might also exhibit enrichment in the same tissues. The results indicated that genetic variants related to frailty were significantly enriched in 11 brain tissues after correction p values, which were all overlapped by the tissues in which schizophrenia associated genetic variants enriched (Fig. 4 and Table S5). In addition, Brain Frontal Cortex BA9 (betaschizophrenia = 0.098, p = 9.21 × 10−27; betafrailty = 0.042, p = 9.57 × 10−8) and Brain Cortex (betaschizophrenia = 0.097, p = 1.20 × 10−24; betafrailty = 0.041, p = 3.36 × 10−7) were the top 2 significant enriched tissues for both frailty and schizophrenia.

The red dashed line is the Bonferroni corrected significant level. Tissues that showed significant enrichment (corrected p value < 0.05) are in red.

Shared genes identified by SMR

Since the tissue enrichment analyses demonstrated that genetic variants related to frailty and schizophrenia were both significantly enriched in brain tissues, we further conducted the SMR analyses using the brain cis-QTL to investigate the shared genes between frailty and schizophrenia. The results of SMR presented that there were 101 genes associated with frailty, and the top 3 genes were SULT1A1 (pHEIDI = 0.269, NSNPs_HEIDI = 20, pSMR = 1.56 × 10−9), AFF3 (pHEIDI = 0.098, NSNPs_HEIDI = 20, pSMR = 6.02 × 10−9), ADCY3 (pHEIDI = 0.240, NSNPs_HEIDI = 20, pSMR = 1.18 × 10−8), respectively (Supplementary Table S6). We subsequently compared the identified risk genes for frailty with the risk genes for schizophrenia reported by Trubetskoy et al.18, and we found that 2 risk genes, DCC and NEGR1, were shared between frailty and schizophrenia. The detailed results are presented in Table 1.

Causal relationship between frailty and schizophrenia

Causality inferred by Mendelian randomization

Based on the aforementioned criteria, a total of 21 and 111 SNPs related to frailty and schizophrenia are respectively utilized to perform the bidirectional MR analyses, and the proportions of variance explained by their corresponding data sets are 0.129 and 18.340% (Supplementary Table S7).

The results of MR estimations on the directional relationship between frailty and schizophrenia are displayed in Table 2. The Cochran’s Q tests indicate there is no obvious heterogeneity among the SNPs associated with frailty or schizophrenia. Therefore, the effect sizes were evaluated by the fixed-effect IVW method. The IVW method presents frailty is positively correlated with the risk of schizophrenia (OR: 1.763, 95% CI: 1.259, 2.468, p = 0.001), and this association is supported by the weighted median (OR: 1.697, 95% CI: 1.057, 2.729, p = 0.029), MR-PRESSO (OR: 1.763, 95% CI: 1.316, 3.021, p = 0.001), and MR-cML (OR: 1.749, 95% CI: 1.209, 2.529, p = 0.003) methods. Reversely, the IVW method indicates that schizophrenia patients are more likely to be frail (β: 0.012, 95% CI: 0.006, 0.018, p < 0.001), and the supplemented methods including weighted median, MR-PRESSO, and MR-cML also provide similar estimations. The scatter plots of SNP potential effects on exposure versus come are demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. S3, with the slope of each representing the evaluated effect size per method.

Sensitivity analyses present that there are no significant horizontal pleiotropies among the two instrumental data sets (p = 0.639 for frailty as exposure and p = 0.375 for schizophrenia as exposure, Table 2). The significant and bidirectional causal relationship between frailty and schizophrenia is not driven by single genetic variants (Supplementary Fig. S4 and Table S8).

Evaluation of MR assumptions

Firstly, for the relevance assumption, SNPs were selected from large-scale GWAS using a stringent significance threshold (p < 5 × 10−8), ensuring that the selected SNPs were robustly associated with the exposures. Moreover, SNPs were unlikely to suffer from weak instrument bias since those with an F-statistic lower than 10 were excluded; Secondly, the modified Cochran’s Q test was conducted to identify and exclude any outlier pleiotropic SNPs, thereby satisfying the independence assumption. Thirdly, for the exclusion restriction assumption, SNPs were clumped using a strict LD threshold and the MR-Egger regression intercept test did not detect any evidence of pleiotropy. In summary, our MR analysis rigorously adhered to the three assumptions and provided robust causal inference, which is unlikely to be influenced by possible confounders, such as co-morbidity, lifestyle factors, and medication.

Discussion

Our study investigated the genetic association and causality between frailty and schizophrenia from the genetic perspective based on the large-scale GWASs summary data. First of all, the global genetic correlation analyses presented they were positively associated, and the local genetic correlation demonstrated they were locally correlated in three genomes. Furthermore, the condFDR/conjFDR method indicated there were 111 genomic loci in total which are jointly associated with both frailty and schizophrenia. In addition, the tissue enrichment and SMR analyses demonstrated the genetic variants related to frailty and schizophrenia have overlapped tissue enrichments and functional genes in the brain. Lastly, the MR results implied there was a bidirectional causal relationship between frailty and schizophrenia.

The global genetic correlation analysis revealed a positive genetic association between frailty and schizophrenia. This finding aligns with several epidemiological studies, which consistently demonstrate that the prevalence of frailty is significantly higher in patients with schizophrenia compared to controls16,35. However, the global genetic correlation coefficients are relatively low (rg = 0.101–0.117). Other psychiatric traits and disorders, such as neuroticism36, insomnia37 and depression7, have also shown bidirectional causal relationships with frailty. In addition, our previous study indicated a significant genetic correlation between frailty and depression, with an rg of 0.6177. These findings suggest that while there is a relationship between frailty and schizophrenia, the psychiatric traits and diseases most strongly associated with frailty are likely not schizophrenia.

Additionally, we examined their local genetic correlation and discovered they were correlated in 202 genomic regions, while only three of these remained significant after correction for multiple tests. The gene NFIL338 in the first region (chr9: 94167203-96671698) and five genes in the second region (chr11: 112459488-114257728) including NCAM139, DRD240, HTR3A41, HTR3B41, and ZBTB1642, were involved in the pathobiology of schizophrenia. While the relevant studies on frailty were relatively limited, we did not find any risk genes that had been studied for frailty in these three regions.

We further identified 111 genomic loci that were shared by frailty and schizophrenia via the pleioFDR software, among which the most significant locus is located in chromosome 4 (Lead SNP: rs13107325 in the SLC39A8 gene). Currently, multiple studies have not only validated the association between rs13107325 and schizophrenia in Europeans43 but also in Chinese44. Besides, among the 228 independent SNPs in the shared genomic loci, an appropriate 10% were located in the three local genomic regions identified by the local genetic correlation analyses: 5 SNPs (rs1351117, rs10992733, rs10821168, rs10761245, rs10761247) in chr9: 94167203-96671698, 13 SNPs (rs17529477, rs10891564, rs7107293, rs78169211, rs12420205, rs10891570, rs12222458, rs10891571, rs4373974, rs6589386, rs75059851, rs733856, rs12277680) in chr11: 112459488-114257728, and 6 SNPs (rs55905661, rs12457876, rs586275, rs71367544, rs516890, rs62103240) in chr18: 77149991-78017158. These results further emphasized the 3 locally correlated loci play an important role for both traits.

The results of tissue enrichment indicated the tissues in which genetic variants related to frailty enriched were all brain tissues and completely overlapped by schizophrenia associated genetic variants. In addition, their top 2 significant enriched tissues were the Brain Frontal Cortex BA9 and Brain Cortex. These findings were consistent with the existing results that frailty was associated with reduced cortex volume45, and increased cortical brain infarcts46. Meanwhile, schizophrenia patients also have widespread cortical thinning and smaller cortical surface area, especially in frontal and temporal lobe regions47.

Based on the findings from the shared enrichment of tissue types, we further applied the brain cis-QTL and SMR method to explore their shared risk genes in the brain, and we identified 101 risk genes for frailty, two of which were found to be shared between these two traits. The shared genes are reported to play important roles in central nervous systems. For instance, Deleted in Colorectal Cancer (DCC) has shown a significant association with various psychiatric diseases, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression, according to the PGC cross-trait GWAS studies48. Functional studies have suggested that DCC may participate in axonal guidance49 and regulate synaptic function and plasticity50, indicating its potential contribution to these diseases by affecting synapse functions. Another gene, Neuronal growth regulator 1 (NEGR1), has been reported to be significantly associated with depression and schizophrenia43,51. Dysregulation of NEGR1 protein and gene transcript has been observed in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) region of individuals with schizophrenia52,53. NEGR1 is known to participate in cell adhesion and belongs to the IgLON superfamily54, which is associated with various central nervous functions such as intelligence55, learning, and behavior56,57. Additionally, NEGR1 has been reported to regulate synapse formation in hippocampal neurons58 and hippocampal neurogenesis57. Both DCC and NEGR1 have functions in synapses, suggesting that they may play a role in mediating the connection between schizophrenia and frailty.

Given that genetic association analyses have shown a substantial shared genetic basis between frailty and schizophrenia, we further employed the MR design to assess the causal relationship between the two traits, revealing a bidirectional causality. Several potential mechanisms may explain why individuals with schizophrenia are more prone to frailty. A growing body of evidence indicates that oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are elevated in patients with schizophrenia compared to the general population, play a critical role in the development of frailty59. In addition, frailty is a reflection and indicator of the aging process, thus, the accelerated aging hypothesis may also play a role. Basic research has shown that leukocyte telomere length, a marker of cellular aging, is significantly shortened in individuals with schizophrenia, suggesting an increased risk of frailty16. Furthermore, schizophrenia can induce neurobiological changes, such as neuronal loss and synaptic dysfunction, which contribute to brain aging and the development of frailty60.

The role of frailty in the development of schizophrenia has been largely overlooked, with limited reports available. This may be due to the traditional perception of frailty as a condition predominantly affecting older adults. However, frailty is also notably prevalent among young and middle-aged populations, with prevalence ranging from 3.9% to 63%61, posing potential threats to health and increasing disease burden. Regarding the rationale of frailty as a potential cause of schizophrenia, our systematic genetic association analyses revealed an extensive shared genetic architecture between the two conditions. Additionally, previous studies based on frailty diagnostic criteria may offer potential explanations. For example, an MR analysis by Iob et al. found that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity can reduce the risk of schizophrenia62, and, randomized trials demonstrated that physical activity interventions significantly improve psychiatric symptoms and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia63,64. Apart from physical activity, a strong relationship has been identified between walk slowness, handgrip strength, and the functional status of schizophrenia patients65,66, consequently, strength training programs have been recommended to enhance muscle strength and alleviate psychopathology67. In summary, our MR analysis revealed that frailty is associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia, offering valuable insights for future research.

Our study has several strengths worth pointing out. Firstly, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship including the genetic association and causality between frailty and schizophrenia. Secondly, multiple statistical methods were performed to explore their genetic association, which improved the stability and reliability of our findings. Thirdly, our study implemented the two-sample MR analyses based on the genetic data from the large-scale GWASs, making the causality inference robust and unlikely to suffer from the bias from conventional observational studies, such as reverse causality, confounding factors, etc.

Despite these strengths, our findings should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. Firstly, the current study lacked ethnic diversity as the GWAS summary statistics were largely derived from individuals of European ancestry. Therefore, it is necessary to validate the findings in other ethnicities and conduct trans-ethnic GWAS to obtain more comprehensive results. Secondly, it is important to note that GWAS only captures the association between common genetic variations and phenotypes. However, a complete understanding of the genetic components underlying disease risk requires consideration of other types of genetic variants, such as structural variations68. Therefore, further studies should be conducted if data on these variants are available for both schizophrenia and frailty. Moreover, the frailty index is another widely used tool for assessing frailty, based on 44 or 49 self-reported items covering symptoms, disabilities, and diagnosed diseases. In our study, we selected the FFS due to its simplicity and practicality. The differences between these tools may result in varying findings, underscoring the need for further investigation. Lastly, while we identified several shared genomic regions and genes between frailty and schizophrenia, further vitro and in vivo experiments are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying how these shared genetic components contribute to both traits.

Conclusions

Based on the summary genetic data from the large-scale GWASs, our study uncovered the shared genetic components between frailty and schizophrenia and illustrated their bidirectional causal relationship, which provided new evidence for their close relationship and would further be helpful for the prevention and intervention of frailty and schizophrenia.

Responses