Cardiovascular comorbidities in Chinese inpatients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders

Introduction

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) are characterized by the highest premature mortality due to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). The risk of death due to CVD in patients with SSD is 2–3 times higher than that of the general population, resulting in a 10–20-year reduction in life expectancy1,2,3. In addition, due to drug interactions, lower tolerance to antipsychotics, and poor medication adherence, comorbid CVDs can significantly increase the risk of schizophrenia (SCZ) relapse4.

Comorbidity is often defined differently depending on the research focus5. A Survey revealed that 75% of hospitalized SCZ patients in New York State have at least one comorbid condition6. Previous studies have primarily categorized SCZ comorbidities into two main groups: mental disorders and physical illnesses. Mental comorbidities include substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression7, while physical comorbidities include type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension8,9,10,11. CVDs comorbidities, such as hypertension, myocardial infarction12, tachycardia8, and heart failure13.

Increasing evidence indicates that the shared etiology between SCZ and CVDs encompasses biological, genetic, and behavioral mechanisms14,15. Research demonstrated extensive genetic overlap among risk factors for these conditions, with shared loci potentially exhibiting bidirectional effects, which might underlie the variance in comorbidities16,17. Individuals with SSD also exhibit higher rates of smoking and alcohol use, which in turn are risk factors for CVD. The impact of antipsychotic medication on comorbidities has garnered clinical attention due to the excessive metabolic dysfunction observed in these patients, which is significantly associated with adverse cardiac metabolism and an increased risk of CVDs and mortality18,19. Conversely, results suggested that adherence to antipsychotic medication may reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease, and efforts to improve medication compliance could enhance CVD outcomes in patients with SCZ20. Previous studies have primarily reported the association between commonly used antipsychotics—such as haloperidol, aripiprazole, clozapine, and olanzapine—and CVD risks21,22,23. However, there is still a lack of comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between psychotropic use and CVD comorbidities in patients with SCZ.

Understanding the patterns and determinants of comorbidity is crucial for alleviating the disease burden. Utilizing individualized clinical data can better characterize these phenomena, identify high-risk populations, and provide insights for causal inferences between diseases. By a representative sample of SSD patients with Mandarin Chinese ancestry, we aimed to employ a model-based approach to identify and describe the clustering of CVD comorbidities in patients with SCZ. We also explored the relevant factors of comorbidity patterns, especially psychotropic medication use. We hypothesized significant differences in demographic characteristics, psychotropic medication usage, and regional economy across the comorbidity patterns.

Material and methods

Data sources

Based on the multicenter research collaboration project coordinated by Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, EMR data were collected from a municipal tertiary psychiatric specialty hospital in Beijing, a provincial tertiary general hospital in Guizhou, and a tertiary psychiatric specialty hospital in Lincang, Yunnan Province. We collected patient demographic and treatment records, including gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, employment status, regions, and psychotropic medication usage. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Huilongguan School of Clinical Medicine [(2023) Research no. 104], and all data has been anonymized.

Study sample

Patients inclusion criteria: (1) Admission and discharge dates between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2023; (2) According to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), diagnosed with Schizophrenia, Schizotypal, and Delusional Disorders (SSDD), classified under ICD-10 codes F20-F29, by at least two attending psychiatrists; (3) Comorbid CVD documented at discharge, conforming to ICD-10 codes I00-I99; (4) Complete age and gender information; (5) For patients with multiple admissions, only the clinical data from the last admission during the study period were included. Exclusion Criteria: (1) Multimorbidity of other psychiatric disorders such as organic mental disorders, intellectual disabilities, substance dependence, and bipolar disorders; (2) Incomplete clinical data (eFig. 1 in Supplement 1).

Quality control

The data on hospitalized patients from the three hospitals underwent strict quality control at every stage, including data collection, tracing outliers, standardization, storage, sample selection, and variable definition. First, the team communicated with technicians from the information centers of each hospital to confirm that the data storage methods were consistent. The accuracy of the data extraction codes was rigorously checked to avoid errors or omissions. Next, eligibility was determined using logical rules based on admission, discharge, diagnosis, and order dates. Finally, outliers for each variable were identified through data distribution analysis and validated retrospectively using the medical record system.

Measures

First, the diagnostic names and codes from the three hospitals were standardized according to the ICD-10 system, ensuring consistency across different versions by converting older ICD-9 codes and rectifying non-standardized diagnoses. The ICD-10 coding system, comprising letters and numbers, is organized hierarchically into chapters, sections, categories, subcategories, and specific diagnoses. Next, our study used category-level diagnostic names and codes as the fundamental units for defining diseases in subsequent analyses, aiming to mitigate diagnostic variability caused by factors such as the medical institution, year of diagnosis, and clinician expertise. For example, Paranoid schizophrenia (F20.0) and Hebephrenic schizophrenia (F20.1) were both grouped under the broader category of Schizophrenia (F20). Comorbidity was defined as the presence of at least one co-occurring CVD in patients with SSDs.

The records of psychotropic medication use were standardized and classified according to the names of Chinese prescriptions in the treatment records. Specifically, the names of the same medication across different formulations, manufacturers, and specifications in the three hospitals were normalized to their generic names. After that, the psychotropic medications were categorized into five types: typical antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics, anxiolytics and sedatives, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers.

Statistical analysis

In recognizing comorbidity patterns, the first step involved using a counting method to assess the categories, frequencies, and proportions of CVD comorbid with SSD. Also, describe the distributions of single, binary, and triple comorbidity combinations. We visualized and elucidated the relationships between diseases using a comorbidity network diagram, also known as a network map or node-link diagram. This graphical model employs nodes, vertices, and connecting lines to display relationships between entities. After testing different layout algorithms, the Kamada–Kawai algorithm was selected. Its fundamental logic positions nodes in a two-dimensional or three-dimensional space such that all edges are more or less equidistant, with minimal edge crossing24.

The second step utilized latent class analysis (LCA) to identify comorbidity patterns. LCA is a statistical method that classifies individuals based on distinct response patterns to observed categorical variables, aiming to identify group heterogeneity. This approach groups individuals with similar response patterns into the same latent class, minimizing within-class differences and maximizing between-class differences. Rather than relying solely on frequency-based classifications, LCA provides a more nuanced understanding of group structures, revealing the proportion of individuals in each class and enabling further investigation into the characteristics of each group. By using fewer mutually exclusive latent classes, LCA efficiently summarizes and explains the probabilities of different observed variables, serving as a powerful dimension-reduction tool25. We used the category-level names from the ICD-10 coding system for all CVDs diagnoses as manifest variables in the LCA (a total of 50 categories). Conditional probabilities indicate the likelihood of an individual’s response across different manifest indicators. We iteratively fitted models for 2–6 classes, selecting the best model based on the smallest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), other fit indices, and clinical relevance26.

In investigating factors associated with comorbidity patterns, Pearson’s Chi-squared or Fisher’s test was used in univariate analysis to examine differences between patterns. Factors demonstrating both statistical significance and clinical relevance were incorporated in the multivariate analysis. Multinomial logit analysis was used to evaluate the impact of multiple factors on the probability of comorbidity patterns, calculating odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The multinomial logit regression model, an extension of the binary logistic regression model, estimates the probability of an individual being categorized into a particular class, with a controlled category as the reference group. Demographic characteristics and psychotropic medication use were incorporated as independent variables in the analysis.

Analyses were conducted using R software version 4.3.2. Categorical data were described using frequencies (n) and percentages (%). All tests were 2-sided, with a significance level set at 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 16,344 inpatients across three hospitals were diagnosed with SSDs, of whom 2830 (17.32%) had comorbid CVDs (Table 1) Among these 2830 patients, psychiatric diagnoses were primarily distributed across seven categories, with Schizophrenia (F20) accounting for the largest proportion (80.32%), followed by acute and transient psychotic disorders (F23) (11.45%) and schizoaffective disorders (F25) (6.75%). The proportions for other SSD diagnostic categories were significantly lower. Patients with SSD had comorbidities with 50 CVD diagnoses, among which Primary Hypertension (I10) was the most common (46.15%), followed by Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease (I25) (17.31%) and Heart Failure (I50) (14.49%) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Table 2 reports the demographic characteristics of SSD patients with CVD comorbidities, where males (55.69%) outnumbered females (44.31%). The average age was 53 years, with 56–70 years accounting for the heaviest proportion (36.54%), followed by 41–55 years (26.01%) and those aged 70 years and above (13.78%). The Han ethnic group (93.50%) significantly outnumbered the minority ethnic group (6.50%).

Proportion of diseases and comorbidity patterns

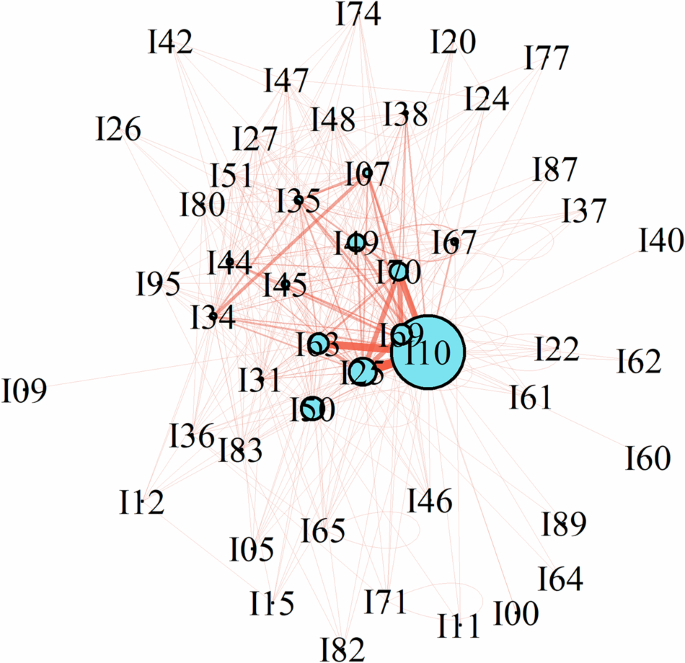

The majority of SSD patients (1893 cases, 66.90%) had a single CVD comorbidity (eFig. 2 in Supplement 1). Primary hypertension (24.95%) was the most prevalent, followed by heart failure (12.61%) and chronic ischemic heart disease (5.69%) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). There were 470 cases with two CVD comorbidities (16.60%), with the most common combination being primary hypertension and sequelae of cerebrovascular disease (6.71%) (eTable 3 in Supplement 2), 8.66% had three conditions (eTable 4 in Supplement 2), and 7.84% had four or higher number of comorbidities. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships among CVD derived using the network diagram method, primarily identifying primary hypertension (I10) as the central node of the network. The primary connections in the network include sequelae of cerebrovascular disease (I69) and chronic ischemic heart disease (I25).

Network nodes represent different ICD-10 codes for cardiovascular system diseases (CVDs) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Larger nodes signify higher disease proportion. The lines between nodes depict the connections between CVDs, with the thickness of these lines reflecting the frequency of their co-occurrence.

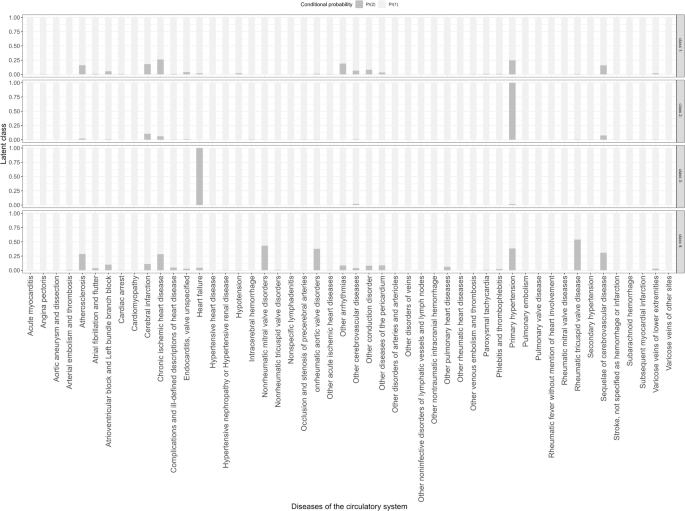

The comorbidity patterns of CVD in SSD were further identified through LCA, with a four-group solution providing the best fit to describe these patterns (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). We identified four comorbidity clusters, named according to their dominant features (Fig. 2): 47.86% by having a lower risk of various CVDs (conditional probabilities < 0.25), hence named the ‘low-CVDs Risk’ cluster. In addition, 30.15% predominantly consisted of patients at high risk for primary hypertension (conditional probability = 1), named the ‘primary hypertension’ cluster. 12.99% of patients were mainly at high risk of heart failure (conditional probability = 1), named the ‘heart failure’ cluster. 8.99% of patients were primarily at high risk for rheumatic tricuspid valve disease and nonrheumatic mitral valve disorder (conditional probabilities: 0.43–0.58), named the cardiac valve and vascular disorder cluster.

Dark gray bars correspond to the left scale, indicating conditional probabilities (0–1).

Univariate analysis indicated significant statistical differences in demographic characteristics and psychotropic drug use among the four patient groups (Table 2). Notably, the heart failure cluster differed from other clusters, with a higher proportion of males (87.73%), 26-40 age group (37.33%), single (60.00%), unemployed (46.67%), and Southwest region (98.40%). In contrast, the other clusters had a comparable proportion of gender, with a notable concentration in the 56–70 age group, Han ethnicity, married status, and Northern China. Regarding the use of psychotropic medications, typical antipsychotics in each cluster were predominantly Haloperidol. For atypical antipsychotics, Risperidone and Olanzapine were the most commonly used across all groups. In the category of anxiolytics and sedatives, Lorazepam was the primary medication in all clusters. Similarly, Escitalopram Oxalate was the predominant antidepressant across all groups. For mood stabilizers, Magnesium Valproate was the main medication in the Heart Failure and Primary Hypertension clusters, while Sodium Valproate was more commonly used in the other two clusters.

Associated factors of comorbidity patterns

Multivariable analysis (Table 3), with the low-risk CVDs group as the reference, showed that males were significantly more likely than females to have comorbidity patterns associated with primary hypertension (OR = 1.15) and heart failure (OR = 5.36). Compared to patients aged 25 and under, those older than 26, particularly in the 41–55 age group (OR = 12.82), showed a higher likelihood of comorbidity with primary hypertension. Patients over 40 were more likely to have comorbidities within the cardiac valve and vascular disorders, with the highest odds in those aged 70 and above (OR = 4.54). Patients older than 26 were less likely to have comorbidities associated with the Heart Failure group.

Ethnic minorities, compared to the Han population, were more likely to have comorbid heart failure cluster (OR = 1.50) but less likely to have comorbid cardiac valve and vascular disorders cluster (OR = 0.12). Compared to single patients, those in other marital statuses, especially married individuals (OR = 2.45), showed a higher probability of comorbidity with primary hypertension cluster, while others were less likely to have comorbid heart failure cluster (OR < 1.00). Married patients also had a higher probability of cardiac valve and vascular disorders (OR = 1.52). Compared to patients with an educational level of primary and below, those with higher levels, notably higher education (OR = 1.94), were more likely to have comorbid primary hypertension cluster. Blue-collar workers (OR = 1.41) were more likely to have comorbid primary hypertension clusters than unemployed patients. Patients from the northern regions of China were more likely to have comorbidities within the cardiac valve and vascular disorders class (OR = 62.52) and less likely to have primary hypertension cluster (OR = 0.38) than those from southwestern.

Compared to patients not treated with typical antipsychotics, those treated with haloperidol (Injection) (OR = 2.07), perphenazine (OR = 22.06), and chlorpromazine hydrochloride (OR = 7.09) had a higher likelihood of comorbid heart failure cluster. Patients on perphenazine also showed a higher probability of comorbid primary hypertension cluster (OR = 1.98), while those who use sulpiride (OR = 0.33) have fewer comorbid it. Use of haloperidol (injection) (OR = 0.61) and haloperidol decanoate (long-acting injection) (OR = 0.34) was associated with a lower probability of comorbid cardiac valve and vascular disorders. Compared to patients not treated with atypical antipsychotics, those who used amisulpride (OR = 1.76) were more likely to have comorbid primary hypertension cluster. Fewer comorbid heart failures cluster were observed using risperidone (OR = 0.35), olanzapine (OR = 0.42), clozapine (OR = 0.46), aripiprazole (OR = 0.34), quetiapine fumarate (OR = 0.21), paliperidone palmitate (OR = 0.23), and amisulpride (OR = 0.23).

Compared to patients not treated with anxiolytics and sedatives, those treated with lorazepam (OR = 0.79) exhibited a higher likelihood of comorbid primary hypertension. Use of lorazepam (OR = 2.46), diazepam (OR = 4.79), estazolam (OR = 4.54), oxazepam (OR = 2.56), midazolam (OR = 3.28), dexzopiclone (OR = 5.46), clonazepam (OR = 3.02), and zaleplon dispersible (OR = 6.02) was associated with a higher likelihood of comorbid heart failure. Patients treated with lorazepam (OR = 1.42), diazepam (OR = 1.60), dexzopiclone (OR = 1.81), and alprazolam (OR = 1.86) were more likely to have comorbidities within the cardiac valve and vascular disorders category. Compared to patients not treated with antidepressants, those treated with escitalopram oxalate (OR = 1.47) and other antidepressants (OR = 1.51) exhibited a higher likelihood of comorbid primary hypertension cluster. Fewer comorbidity heart failure cluster (OR = 0.15) using escitalopram oxalate. Less comorbid cardiac valve and vascular disorders using escitalopram oxalate (OR = 0.49) and other (OR = 0.34). Compared to patients not treated with mood stabilizers, those treated with sodium valproate (OR = 0.63) had a lower likelihood of comorbid primary hypertension. More comorbid heart failures using magnesium valproate (OR = 3.31) and lithium carbonate (OR = 3.82) (detailed information on the use of psychotropic drugs, eTable 6 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

We identified four distinct CVD comorbidity patterns of patients with SSDs: Low-risk CVDs, Primary Hypertension, Heart Failure, and Cardiac Valve and Vascular Disorders clusters. These patterns were influenced by multiple factors such as gender, age, and geographic region. Notably, they were significantly associated with the use of different psychotropic medications, reflecting variable SSDs clinical trajectories and prognoses. These findings offer valuable insights for targeting high-risk groups and guiding future research on comorbidity factors.

In our study, the majority of patients with SSD were diagnosed with SCZ (80.32%), which aligns with findings from previous studies conducted in Dalian of China27, South Korea28, and Denmark29. SCZ is characterized by high diagnostic stability and receives considerable clinical attention30. Increasing evidence indicates that individuals with SCZ are at a heightened risk for CVD1,4,31. However, clinical observations reveal that these patients undergo fewer CVD screenings and receive lower-quality treatment. Addressing these gaps in diagnosis and treatment is crucial for improving patient quality of life and reducing mortality32. Meta-analyses reported a CVD prevalence of 11.8% among SCZ patients2, though findings vary. For instance, the prevalence among inpatients at five psychiatric hospitals in France is 4.6%33, indicating regional disparities. Our study found that 17.32% of SSD patients have comorbid CVD, with 66.90% having one type of CVD and 47.86% classified as low-risk for CVD. This research complements previous research by comprehensively identifying comorbidity with all CVDs.

Meta-analysis indicated a hypertension prevalence of 39% among patients with SSD34. In the presented analysis, the proportion of primary hypertension (24.95%) was significantly higher than others. It contrasts with Beijing, China (12.80%).8 Psychiatric disorders may increase the risk of hypertension through various mechanisms, including the use of antipsychotic drugs, systemic inflammation, and irregular autonomic nervous system activity11,35. Additionally, hypertension is more readily detectable, which may lead to better screening and preventative treatment in clinical practice. In our study, the comorbidity network diagram highlighted the connections between CVDs, underscoring its pivotal role in the clinical trajectory. It potentially influences related CVDs and can affect distant organs, such as the brain and liver.8 Sequelae of CVD and chronic ischemic heart disease (IHD), serving as primarily connected nodes, may act as pathways or bridges linking different disease groups and transmitting risk factors or symptomatic impacts36. Meta-analyses show that patients with schizophrenia receive suboptimal hypertension care10, suggesting that the use of comorbidity network diagrams could guide physicians in interdisciplinary collaboration, especially in managing multiple chronic conditions.

Previous research has reported higher rates of CVD comorbidities in SCZ patients compared to mentally healthy controls37,38, along with a notably higher mortality rate than the general population39,40. A study in Beijing, China, did not report comorbid heart failure, while the prevalence was 0.7% in Denmark13 and 1.9% in France33. In our study, the proportion of heart failure among SSD patients was 14.49%, along with a high-risk comorbidity pattern involving heart failure. Mendelian randomization studies have demonstrated a causal relationship between SCZ and an increased risk of heart failure, supporting the theory that SCZ involves systemic dysregulation that adversely affects the heart41,42. Nonetheless, SCZ patients with heart failure often receive more lower-quality care, a shortfall largely attributed to socioeconomic factors and other comorbidities43,44.

In our study, chronic IHD ranked second among CVDs, consistent with previous findings2,45. Cohort studies indicate that patients with psychiatric disorders have a 2–2.5 times higher risk of IHD and stroke compared to non-patients45, accompanied by more than double the mortality risk46. However, IHD remains underreported in patients with SSD47. This study further highlighted cardiac valve diseases as the most common within the cardiac valve and vascular disorders group. Studies have reported retinal vascular abnormalities in schizophrenia patients, which may reflect neurodevelopmental and cerebral microvascular anomalies48,49. The elevated vascular endothelial growth factor levels observed in these individuals suggest that schizophrenia may be linked to abnormal angiogenesis50. Additionally, microvascular abnormalities could contribute to the pathology of SCZ51, supporting the notion that it might be a mild adult vascular-ischemic disorder involving impaired postischemic repair52.

A meta-analysis of 13 cohort studies reported that patients with SCZ have a higher risk of CVD38, with persistent risk factors over time53,54. In the presented analysis, male patients exhibit a higher comorbidity risk than females, particularly for heart failure. In China, the Framingham Risk Score was significantly higher in males55. In contrast, female patients in Japan showed a stronger association with the risk of composite cardiovascular events56. Similarly, in the general population, women have a higher risk of hospitalization due to heart failure57. Our study also found a strong association between age and comorbidity patterns, consistent with previous research58. Notably, younger patients had a higher risk of heart failure. In Denmark, SCZ patients under 55 face a higher risk of death from heart failure compared to those aged 55-64, with the lowest risk observed in patients over 6513. There was also a trend toward younger CVD-related mortality46. Furthermore, we found that minority patients, compared to Han Chinese, have a higher probability of comorbid heart failure and lower-risk CVDs cluster. In the United States, ethnic minorities with severe mental disorders present a higher number of cardiovascular risk factors59. Our study also revealed significant regional variations in diagnosis and comorbidity patterns within SSD. Particularly in Northern China, higher risk of comorbid cardiac valve and vascular disorders cluster, likely due to better regional economic conditions and healthcare systems that facilitate the diagnosis of complex conditions30,47.

Individualized pharmacotherapy provides more clinically relevant estimates of comorbidity risk. Side effects of antipsychotic medications that contribute to CVD include QT interval prolongation, tachycardia, and blood pressure variations2. A previous study suggests that a severe consequence of treating patients with SSD using haloperidol may be sudden death due to heart failure, potentially mediated by chronic haloperidol inhibition of cardiac σ1R23. Furthermore, in clinical practice, physicians may opt for medications that are better suited to a patient’s condition. The broad applicability of such drugs could also account for the significant correlations observed. This study found that patients treated with chlorpromazine hydrochloride had a higher likelihood of comorbid heart failure. Previous research has indicated that the intravenous administration of chlorpromazine demonstrated benefits in patients with moderate to severe congestive heart failure and cardiogenic shock, which may explain the observed strong association60. Our study found a strong association between the use of amisulpride and comorbid primary hypertension. A meta-analysis suggested that the risk of developing metabolic syndrome with amisulpride was significantly lower compared to olanzapine and aripiprazole, which may account for clinicians’ preference for its use21. In our study, comorbid heart failure cluster was negatively correlated with the use of most atypical antipsychotics. While previous studies have not found risk effects with risperidone and olanzapine, clozapine use has been associated with a significant short-term risk of myocarditis and an increased risk of heart failure within 3 years61,62.

Our study observed a negative correlation between the use of lorazepam and the comorbid primary hypertension group. One randomized trial reported no hypertensive risk associated with lorazepam use63, while another found higher diastolic blood pressure post-treatment compared to placebo64. Patients with anxiety exhibit α-adrenergic vasoconstriction, which increases blood viscosity due to vascular fluid leakage into the interstitial space, potentially contributing to hypertension65. Abnormal blood pressure in patients with anxiety is commonly observed, with significant improvements following anti-anxiety treatment66. These risk effects may reflect complex bidirectional associations, suggesting that anti-anxiety treatment could effectively reduce the likelihood of comorbid hypertension in SSD patients. Several studies have reported adverse events with oxazepam67, while midazolam showed fewer adverse effects compared to morphine68. In our study, the use of escitalopram oxalate was associated with a higher likelihood of comorbid primary hypertension and a lower likelihood of heart failure, as well as cardiac valve and vascular disorders. Previous research has shown that escitalopram can reduce hypertension69; however, it does not significantly lower all-cause mortality or hospitalization rates in patients with heart failure and depression70. This may likely reflect psychiatrists’ preferential prescribing practices. Our study found that among mood stabilizers, sodium valproate use was negatively correlated with comorbid primary hypertension, consistent with previous research71. Animal studies further support these findings, showing that the histone deacetylase inhibitor, valproic acid, attenuated blood pressure in both spontaneously hypertensive rats and deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-induced hypertensive rats72,73.

There are several limitations. First, disease diagnosis based on EMRs could result in misclassification or measurement errors, potentially leading to underestimations or omissions. Although we used broader ICD-10 categories rather than the most specific classes, this approach helped reduce measurement errors and minimized variations in diagnostic capabilities across different healthcare institutions and time periods. Second, psychotropic drug use was derived from EMRs, which may not fully capture long-term medication usage. While this study provided detailed information on medication types, it did not account for dosage impacts, highlighting the need for further research to address this aspect. Third, the cross-sectional design introduces the potential for reverse causation in the observed associations. Future prospective studies are necessary to clarify these relationships. Lastly, due to data limitations, we were unable to include body mass index (BMI), a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and future research should consider quantifying its effects.

Conclusion

Using EMRs from various regions of China, we identified four distinct CVD comorbidity patterns and specific high-risk groups of SSD inpatients. Hypertension and heart failure, in particular, warrant attention in both clinical treatment and community-based patient management. Significant differences were observed in demographic characteristics and psychotropic medication use. The occurrence and progression of these comorbidities may follow diverse clinical trajectories and prognoses, providing clinicians with essential insights for interdisciplinary treatment and management of multimorbidity. These findings also contribute to the formulation of early screening and prevention strategies.

Responses